Abstract

A critical amount of energy reserve is necessary for puberty initiation, for normal sexual maturation and maintenance of cyclicity and fertility in females of most species. Therefore, the existence of circulating metabolic cues which directly modulate the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis is predictable. The adipocyte-derived hormone leptin is one of these cues having been studied extensively in the context of regulating the reproductive physiology. Humans and mice lacking leptin (ob/ob) or leptin receptor (LepR, db/db) are infertile. Leptin administration to leptin-deficient subjects and ob/ob mice induces puberty and restores fertility. LepR is expressed in brain, pituitary gland and gonads, but studies using genetically engineered mouse models determined that the brain plays a major role. Recently, it has been made clear that leptin acts indirectly on gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-secreting cells via actions on interneurons. However, the exact site(s) of leptin action has been difficult to determine. In this review, we discuss the recent advances in the field focused on the identification of potential site(s) or specific neuronal populations involved in leptin's effects in the neuroendocrine reproductive axis.

Key Words: Hypothalamus, Hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis, Gonadotropin-releasing hormone, Luteinizing hormone, Metabolism

Introduction

A critical amount of energy reserve is necessary for puberty initiation, for normal sexual maturation and maintenance of cyclicity and fertility in females of most species [1,2]. Ovulation is usually suppressed when a mammal is in negative energy balance, whether that state is caused by inadequate food intake, excessive locomotor activity or increased thermoregulatory costs. If excessive leanness occurs in young women, puberty is often delayed [3]. Puberty is a complex process which involves changes in maturation of reproductive organs, physical manifestations of steroids hormones and establishment of the reproductive capacity [4]. The onset of puberty is marked by an increase in gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion in a defined temporal manner. When puberty develops normally, sexual maturity is achieved and the secretion of gonadotropins becomes pulsatile, consisting of variable but well defined secretory pulses across the estrous (menstrual) cycle. This pulsatile release of GnRH is obligatory to sustain normal gonadotropin synthesis and secretion, cyclicity and ovulation. Food restriction, excessive exercise and other energetic challenges suppress GnRH pulsatility, and thereby disrupt cyclicity and fertility, and may delay the onset of puberty [3,5,6]. Therefore, the existence of a number of metabolic cues which impinge on GnRH neurons is predictable. The adipocyte-derived hormone leptin is one of these cues having been studied extensively in the context of regulating the reproductive axis.

Leptin Action on Reproduction

Mice lacking leptin (ob/ob) or leptin receptor (LepR, db/db) develop hyperphagic obesity, diabetes and a variety of neuroendocrine dysfunctions [7,8]. These mice exhibit low gonadotropin levels, incomplete development of reproductive organs and do not reach sexual maturation. Leptin treatment to ob/ob mice, but not weight loss alone, induces puberty, maturation of the gonads, gonadotropin secretion and restores fertility [9,10]. Humans with mutations in leptin or LepR genes recapitulate most of the leptin-deficient reproductive phenotype observed in mouse models [11]. In leptin-deficient subjects, leptin treatment induced an increase in the levels of gonadotropins and estradiol, as well as enlargement of the gonads and normal pubertal development [11]. Leptin levels fall on starvation, a response that drives many of the neuroendocrine changes observed in this condition, including those related to the reproductive neuroendocrine axis [12]. Thus, during states of negative energy balance, as in fasting, animals from many species exhibit decreased luteinizing hormone (LH) levels. Leptin administration blunts the fasting-induced suppression of LH secretion and restores fertility [12,13,14]. In women with hypothalamic amenorrhea resulting from conditions of negative energy balance, leptin treatment increased pulse frequency and mean levels of LH, ovarian volume, the number of dominant follicles and estradiol levels [15]. Therefore, also in humans sufficient levels of leptin are required for normal reproductive function.

An important aspect to be mentioned is that the infertility phenotype observed in animal models of leptin deficiency seems to be highly dependent on their genetic background. For example, obese ob/ob mice crossed onto a BALB/cJ strain exhibited improvement of fertility [16]. This phenomenon appears to be sexually dimorphic, as ob/ob males on F2 generation are partially fertile, but females only show improvement of fertility following backcrossing of the ob C57BL/6J mutation for 10 generations into the BALB/cJ genetic background. Moreover, a series of studies performed in seasonal breeders have challenged the concept of leptin action in the reproductive physiology (reviewed in Schneider [17]). In female hamsters, fasting-induced decrease in leptin levels is not always followed by reproductive impairment. In addition, leptin treatment prevents fasting-induced anestrus in female hamster only when oxidable fuels (e.g. fatty acid or glucose) are available. In food restricted re-fed hamster and sheep, plasma leptin does not increase before the restoration of LH pulses and fertility [17,18]. These findings suggest the existence of species differences likely due to exposure to specific evolutionary constraints and development of distinct reproductive strategies. But it also remains unclear whether in these conditions leptin signaling, LepR expression, leptin's transport through the blood brain barrier or the levels of unbound circulating leptin are unchanged.

The LepR is expressed in many different organs and tissues, including every node of the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis [8,19]. Thus, the ability of leptin to regulate reproduction might be attained by direct actions in several cell types. Nevertheless, using genetic strategies, studies showed that selective re-expression of LepR only in the brain of mice otherwise null for LepR restores fertility in both males and females [20]. These studies established that the brain plays a major role.

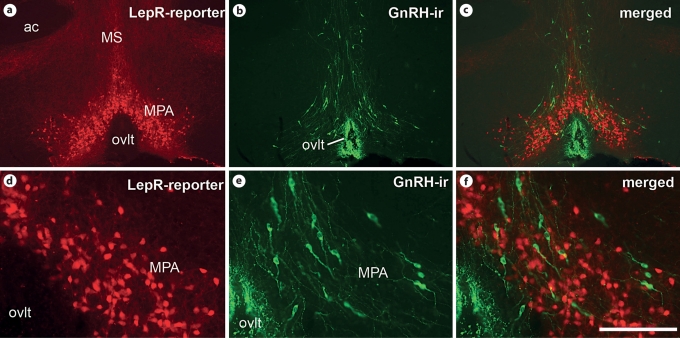

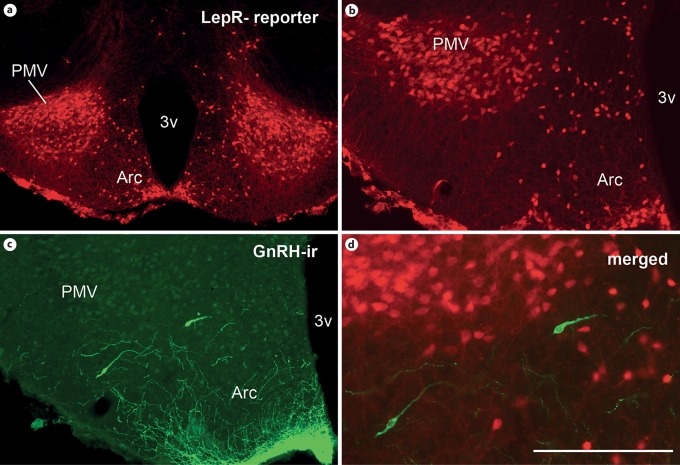

The direct action of leptin in GnRH neurons seemed reasonable, as in vitro studies reported the expression of LepR in immortalized GnRH (GT1) cells [21]. However, these findings have not been reproduced in vivo (fig. 1) and, therefore, leptin direct action in GnRH neurons remained controversial. More recently, with the availability of genetic mouse models which allow selective deletion of LepR from defined neuronal populations, this controversy appears to have come to an end. Mice with selective deletion of LepR from GnRH neurons exhibited normal puberty initiation, sexual maturity, fertility and normal litter sizes [22]. This study determined that if LepR is expressed in GnRH neurons – in low or technically undetectable levels – it is not required for leptin action in puberty initiation and in the coordinated control of the reproductive function. Hence, the identification of leptin-responsive cells afferent to GnRH neurons has been of great interest to the field.

Fig. 1.

Comparative distribution of neurons expressing GnRH and of neurons expressing LepR reporter gene. Neurons expressing LepR were visualized using LepR-IRES-Cre mice crossed with tdTomato reporter mice (B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J, JAX® mice). a–c Fluorescent photomicrograph showing the distribution of neurons expressing LepR (a, c) and of neurons expressing GnRH immunoreactivity (GnRH-ir, b, c) in the medial preoptic area (MPA). d–f Higher magnification of a–c. Observe that some neurons which express LepR are intermingled with GnRH neurons in the MPA (c, f). ac = Anterior commissure; MS = medial septal nucleus; ovlt = vascular organ of lamina terminalis. Scale bar: a–c 800 μm; d–f 200 μm.

The signaling (long) form of the LepR (LepRb) is expressed in several brainstem sites and in many hypothalamic nuclei such as the arcuate, the ventromedial, the dorsomedial and the ventral premammillary [23,24]. In the following sections, we will discuss the recent advances in defining the leptin-responsive neural pathways involved in reproductive control.

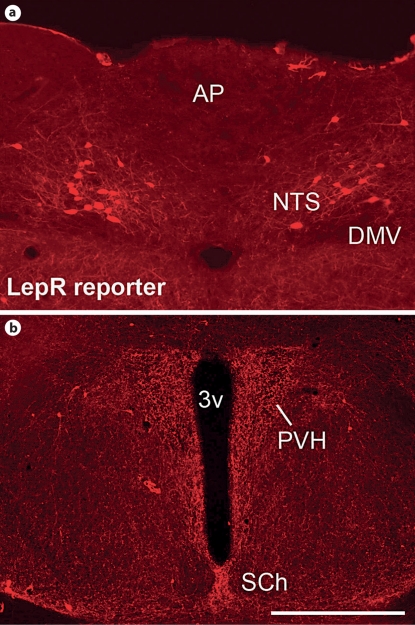

Brainstem

In the brainstem, LepRs and leptin-induced phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (pSTAT3) are found in several nuclei, including the dorsal raphe, the lateral parabrachial, the Edinger-Westphal and the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) [24,25,26]. Of those, special attention has been given to the NTS (fig. 2a). Neurons in the NTS receive sensory inputs conveyed by the vagus nerve and signals from circulating factors conveyed through the area postrema. The area postrema is a closely associated circumventricular organ – positioned outside the blood brain barrier – located in the dorsal border of the medial NTS. Several lines of evidence have indicated that sensory vagal inputs and circulating metabolic cues (e.g. glucose) may reach the reproductive control sites of the central nervous system via the NTS. For example, during fasting, disruption of visceral sensory signals achieved by bilateral vagotomy restored the decreased LH levels characteristic of this condition [27]. Site-specific deprivation of glucose availability in the caudal brainstem decreased LH secretion, suggesting that the area postrema may act as a glucosensor in the modulation of gonadotropins [28]. However, viral delivery of LepR into the NTS of LepR-deficient Koletsky rats did not restore their reproductive function [29]. In addition, selective deletion of LepR only from forebrain nuclei, maintaining intact the expression of LepR in the brainstem, recapitulated the reproductive deficit of leptin-signaling deficiency [22]. These findings suggest that although the caudal brainstem may carry signals from visceral inputs and glucose availability to the reproductive system, it does not relay leptin's effects in reproductive control.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of neurons expressing LepR in the NTS and PVH. Neurons expressing LepR were visualized using LepR-IRES-Cre mice crossed with tdTomato reporter mice (B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J, JAX® mice). a Fluorescent photomicrograph showing neurons expressing LepR in the NTS. Observe the close proximity with the AP. b Fluorescent photomicrograph showing fibers originating from LepR-positive neurons in the PVH. Observe the absence of cell bodies containing the reporter gene within the limits of the PVH. 3v = Third ventricle; DMV = dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve; SCh = suprachiasmatic nucleus. Scale bar: a 200 μm; b 400 μm.

Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus

Food deprivation is a recognized condition of nutritional stress characterized by low leptin levels, decreased LH secretion and high corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) levels. Interestingly, pharmacological blockade of CRH during fasting normalized LH levels [30]. Moreover, prevention of the decrease in leptin levels induced by fasting blunts the activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and prevents the suppression of the reproductive axis [12]. Together, these findings suggested that CRH neurons might mediate leptin's effect to increase LH secretion in states of negative energy balance. It is well defined that the CRH neurons involved in the regulation of the HPA axis are located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH). But the expression of LepR in the PVH is very low (fig. 2b) and the colocalization of LepR in CRH neurons of the PVH is still debatable. This anatomical piece of data indicates that leptin's effect on CRH secretion is achieved via indirect pathways, which are still unrevealed.

Arcuate Nucleus

In the arcuate nucleus (Arc), LepRs are colocalized with proopiomelanocortin (POMC), neuropeptide Y/agouti-related protein (NPY/AgRP) and Kiss1 neurons [31,32,33]. It has been determined that POMC and NPY/AgRP neurons mediate most of leptin's effects in food intake, body weight and glucose homeostasis. These neuronal groups have also been investigated as likely players linking metabolism and reproduction.

The role of POMC neurons in the control of GnRH secretion and the melanocortin action mediating leptin's effect on reproduction have been subjects of intense debate with inconclusive results. For example, administration of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH, one of POMC products) in rats may stimulate or inhibit LH secretion depending on their physiological condition [34]. The lethal yellow (Ay) mice, which display constitutive and ubiquitous expression of the agouti protein – a competitive antagonist of melanocortin receptors, exhibit obesity and abnormal estrous cycles [35]. In normally fed or leptin-treated fasted rats, melanocortin antagonists decreased the steroid-induced LH surge [36]. However, melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) knockout mice have no evidence of infertility [37] and pharmacological blockade of MC4Rs does not prevent the ability of leptin to positively regulate the reproductive axis of ob/ob mice [38]. Moreover, mice with selective deletion of LepR from POMC neurons, from AgRP neurons, or from both POMC and AgRP neurons are fertile and produce normal litter sizes [39,40]. Recently, we described that deletion of both LepR and insulin receptor from POMC cells causes insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism and ovarian abnormalities with late onset of subfertility [41]. Thus, it is not yet clear whether the reproductive deficits observed in some models of melanocortin signaling deficiency are caused by disruption of a direct neuronal regulation of GnRH secretion or are secondary to their impaired metabolic function.

A role for the NPY system in reproduction has also been proposed. Central administration of NPY stimulates feeding and inhibits the reproductive axis [42]. However, the actions of NPY on GnRH secretion remain somewhat controversial. Studies in different species have suggested the existence of a complex dual action of NPY – one inhibitory and one stimulatory – through which endogenous NPY may regulate the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis. These opposing effects depend on several variables, such as the steroid hormone milieu, the stages of development and changes in the expression of sex steroids receptors [6,43]. Likewise, the involvement of NPY neurons in leptin action on reproductive control is unclear. Deletion of NPY gene expression in mice also lacking leptin (ob/ob mice) improves fertility, but NPY null mice display normal reproductive function [44]. Moreover, as mentioned, deletion of LepR from AgRP/NPY neurons causes no fertility deficits [40]. Although very compelling, the experiments using genetically modified mouse models must be interpreted with caution as developmental compensatory mechanisms may have mask some of the relevant effects of POMC or NPY neurons on leptin's effect on reproductive control.

In the Arc, a subset of LepR neurons expresses Kiss1[33]. The role of kisspeptins (the products of Kiss1 gene) and their receptor (Kiss1r, identified as GPR54) in the reproductive physiology is well established. Hypothalamic levels of Kiss1 and Kiss1r mRNA increase during pubertal development and administration of kisspeptin induces vaginal opening (in juvenile rodents), increases LH secretion and induces ovulation [45,46]. Kiss1 or Kiss1r loss-of-function mutations cause hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in humans and mice [47,48,49]. Studies have also indicated that kisspeptin neurons are likely targets of metabolic cues as food restriction decreased Kiss1 mRNA expression in total hypothalamus or in Kiss1 neurons from the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV) [50,51]. As mentioned, food restriction usually produces a condition of low leptin levels; therefore, changes in Kiss1 mRNA expression may be consequent to changes in circulating levels of leptin. In support to this view, leptin-deficient ob/ob male mice exhibited decreased expression of Kiss1 in the Arc, which is partially restored by leptin treatment [33]. But, intriguingly, total hypothalamic expression of Kiss1 (which includes the preoptic area and the Arc) was not changed in ob/ob mice compared either to wild types or to leptin-treated ob/ob mice, except when matched with food-restricted untreated ob/ob mice [52]. This finding indicates that leptin may not be the major metabolic factor regulating Kiss1 expression in conditions of negative energy balance. Another study reported that diabetic streptozotocin-injected male rats displayed decreased levels of hypothalamic Kiss1 mRNA and low circulating levels of leptin, insulin, LH and androgens [53]. Intracerebroventricular administration of leptin, but not insulin, normalized the hypothalamic Kiss1 gene expression, and the circulating levels of LH and androgens. However, it is not clear whether leptin's effect to normalize Kiss1 gene expression is achieved by a direct action or via activation of an indirect pathway that in turn modulates Kiss1 system. Previous studies showed that stereotaxic delivery of LepR into the Arc of LepR-deficient obese Koletsky rats normalized their estrous cycle [29]. These findings suggest that neurons in the Arc, including those expressing Kiss1, play a major role. But the approach used may have generated an artificial response, as LepR may have been expressed in neurons which are not responsive to leptin under normal circumstances. In a more controlled condition, endogenous re-expression of LepR in the Arc of LepR null mice did not restore the reproductive deficits characteristic of leptin deficiency [54]. But in this experimental design injections may have not targeted Kiss1 neurons, and therefore, the role played by Kiss1 neurons relaying leptin's effect is still unsettled.

Recently, several studies have suggested the existence of a complex interplay among Kiss1, POMC and NPY/AgRP neurons in the Arc [55,56]. Hence, it is been proposed that the coordinated action of this intrinsic circuitry may orchestrate the fine control of GnRH secretion by metabolic cues. Further studies are necessary in order to directly assess the physiological relevance of direct leptin signaling in Kiss1 neurons and to reveal their role in the intricate circuitry of the Arc neuronal populations.

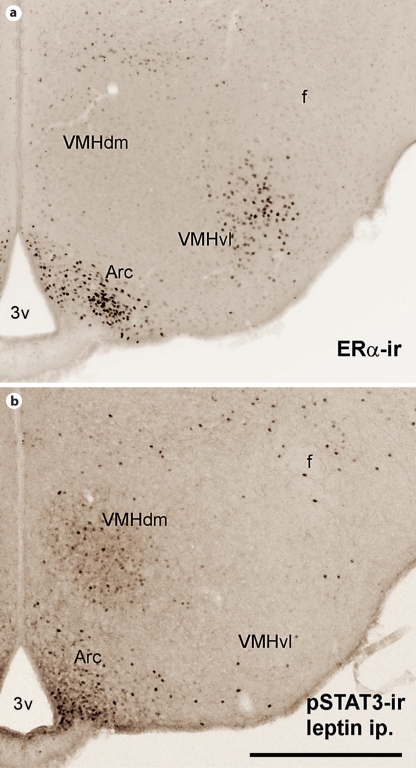

Ventromedial Nucleus of the Hypothalamus

The ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMH) is a complex structure composed of distinct subdivisions with differential connectivity. The ventrolateral subdivision of the VMH expresses a dense concentration of sex steroids receptors (fig. 3a) and is well described to play a role in the female sexual behavior [57,58,59]. Neurons in the dorsomedial subdivision of the VMH express the steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1), LepR and leptin-induced pSTAT3 immunoreactivity (fig. 3b). Deletion of SF-1 selectively from the central nervous system caused disruption of VMH neuronal connectivity and impairment of the female reproductive function [60]. Therefore, the VMH is thought to be a potential leptin target in reproductive control. Using the SF-1 gene promoter to drive Cre expression specifically in VMH neurons, two different groups have demonstrated the physiologic role played by the VMH in leptin's effect on energy homeostasis [61,62]. However, deletion of LepR selectively from VMH neurons did not produce any reproductive deficits in these mice, indicating that leptin signaling in the VMH is not required for leptin's effect on reproduction.

Fig. 3.

Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-α immunoreactivity (ERα-ir) and leptin-responsive neurons in the VMH. a Bright-field photomicrograph showing the distribution of ERα-ir in the VMH. Observe that neurons expressing ERα-ir are enriched in the ventrolateral subdivision of the VMH (VMHvl). b Bright-field photomicrograph showing the distribution of leptin-responsive neurons in the VMH. Leptin-responsive neurons were visualized by leptin-induced phosphorylation of STAT3 immunoreactivity (pSTAT3-ir). Observe that leptin-responsive neurons are enriched in the dorsomedial subdivision of the VMH (VMHdm). 3v = Third ventricle; Arc = arcuate nucleus; f = fornix. Scale bar: 400 μm.

Ventral Premammillary Nucleus

The ventral premammillary nucleus (PMV) expresses a dense collection of LepR (fig. 4) and leptin-responsive neurons [23,63,64]. However, it has remained an unrecognized leptin target and the physiological role played by the PMV in mediating leptin's effects has only recently started to be systematically investigated [64,65]. The PMV expresses sex steroids receptors [59,66] and innervates brain sites related to reproductive control, to the vomeronasal system and to the sexually dimorphic circuitry [67,68]. Using standard tract tracing, we showed that terminals from PMV neurons were in close apposition with GnRH cells in the preoptic area [68]. This preliminary observation was subsequently confirmed by different laboratories using genetically engineered mouse models [64,69]. Additionally, Leshan et al. [64] demonstrated that, in fact, the innervation of GnRH cells by PMV fibers originates from neurons expressing LepR.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of neurons expressing LepR in the PMV. Neurons expressing LepR were visualized using LepR-IRES- Cre mice crossed with tdTomato reporter mice (B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA) 26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J, JAX® mice). a, b Fluorescent photomicrographs showing the distribution of LepR in the PMV. c Fluorescent photomicrographs showing the presence of GnRH-ir in neurons at most caudal levels of the mediobasal hypothalamus. d Higher magnification of b and c (merged image) showing that GnRH neurons are outside the borders of the PMV. 3v = Third ventricle; Arc = arcuate nucleus. Scale bar: a 800 μm; b, c 400 μm; d 200 μm.

The PMV neurons display Fos immunoreactivity – a maker of neuronal activation – following copulation [70]. But copulation is a complex process making the increased Fos expression difficult to interpret. Subsequent studies showed that the exposure to female odors alone is sufficient to induce Fos in PMV neurons [64,71,72,73]. In response to opposite sex odors, male and female from many species exhibit increased circulating levels of gonadotropins [74,75]. In rats, this effect was suppressed by lesions of the PMV [75,76]. Together, these findings suggested that the PMV integrates sexually relevant (odor) environmental signals, the reproductive status (sex steroids) and metabolic cues (leptin). We then hypothesized that PMV neurons relay leptin's effect to increase LH secretion during states of negative energy balance.

As a first approach to test our hypothesis, we performed bilateral excitotoxic lesions of the PMV and assessed different parameters of the female reproductive physiology [65]. PMV-lesioned rats displayed a clear disruption of the estrous cycle for 2 to 3 weeks. After this period, their cyclicity was normalized, but lesions of the PMV caused a permanent deficit in the female's neuroendocrine profile. On proestrus, PMV-lesioned rats exhibited reduction of estradiol and LH levels, of GnRH mRNA expression and a blunted activation of GnRH and AVPV neurons. Of note, in PMV-lesioned fasted rats, leptin treatment failed to increase LH levels. Our findings indicate that PMV neurons are required for leptin stimulation of LH secretion in fasted rats. However, it is worth mentioning that the PMV is comprised of a heterogeneous population of neurons, and therefore, the effects produced by the excitotoxic lesions may be the consequence of disruption of pathways not related to leptin's physiology. Thus, a more selective approach in which leptin signaling is either blocked or endogenously re-expressed in PMV neurons is necessary to determine its physiologic relevance for leptin's effect on reproduction.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The coordination of the reproductive control is essential for the species survival. As noted by different authors, the control of the reproductive physiology involves redundant brain pathways and a number of endocrine players. In this review, we discussed the brain sites potentially involved in leptin's physiological effects in the reproductive neuroendocrine axis. The definitive answer has not been offered, but the availability of genetically engineered mouse models and site-specific manipulations of defined genes have brought a considerable advance to the field (table 1). Neuron-specific targeting with the use of transgenic mouse lines and viral vector delivery in defined brain sites will allow the identification of specific neuronal population(s) relaying leptin's effect in reproductive control. Importantly, these approaches must allow the identification of relevant site(s) of leptin effect during development and in adult life. It is also hoped that modern technologies using in vivo and in vitro approaches to assess site-specific epigenetic changes or alterations in gene expression under metabolic challenges will bring advances to the field. The identification of the related neuronal populations and the molecular basis of leptin's effect on reproductive control is a fundamental step for the understanding of a variety of conditions of impaired fertility derived from metabolic dysfunctions.

Table 1.

Examples of studies employing genetic or pharmacological manipulations to disclose site-specific or cell-specific effects of leptin

| Reproductive phenotype | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|

| Global deletion/blockade | ||

| LepR in the brain | infertility, no pubertal development | 20 |

| LepR in the forebrain | infertility, no pubertal development | 22 |

| Ubiquitous melanocortin antagonism (Ay mouse) | abnormal estrous cyclicity | 35 |

| Melanocortin antagonism (pharmacology) | decreased steroid-induced LH surge; normal leptin effect on reproduction (ob/ob mice) | 36, 38 |

| MC4R deficiency | no deficits reported | 37 |

| NPY knockout | normal fertility | 44 |

| NPY knockout in ob/ob mouse | partial improvement of fertility | 44 |

| Cell-specific deletion | ||

| LepR from GnRH neurons | normal fertility, normal litter size | 22 |

| LepR from POMC neurons | normal fertility, normal litter size | 39 |

| LepR from AgRP/NPY neurons | normal fertility | 40 |

| LepR from AgRP/NPY and POMC neurons | normal fertility, normal litter size | 40 |

| LepR and InsR from POMC neurons | hyperandrogenism, ovarian abnormalities and fertility deficits | 41 |

| LepR from SF-1 neurons | normal fertility, normal litter size | 61, 62 |

| Site-specific reactivation | ||

| Exogenous LepR in the NTS | no rescue of fertility | 29 |

| Exogenous LepR in the Arc | improvement of cyclicity in Koletsky rats | 29 |

| Endogenous LepR in the Arc | no rescue of fertility | 54 |

The consequences of the manipulations for the animal reproductive function are summarized in the second column.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R01HD061539 and Foundation for Prader-Willi Research (to C.F.E.), by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development/CNPq-Brazil 201804/2008-5 (to R.F.), and by the President's Council Award and the Regent's Research Award (UTSW, Dallas, Tex., USA, to C.F.E.).

References

- 1.Kennedy GC. Interactions between feeding behavior and hormones during growth. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1969;157:1049–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1969.tb12936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frisch RE, McArthur JW. Menstrual cycles: fatness as a determinant of minimum weight for height necessary for their maintenance or onset. Science. 1974;185:949–951. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4155.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frisch RE. Fatness, menarche, and female fertility. Perspect Biol Med. 1985;28:611–633. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1985.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plant TM, Barker A, Gibb ML. Neurobiological mechanisms of puberty in higher primates. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10:67–77. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham MJ, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Leptin's actions on the reproductive axis: Perspectives and mechanisms. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:216–222. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill JW, Elmquist JK, Elias CF. Hypothalamic pathways linking energy balance and reproduction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E827–E832. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00670.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue [published erratum appears in Nature 199530;374:479; see comments] Nature. 1994;372:425–432. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tartaglia LA, Dembski M, Weng X, et al. Identification and expression cloning of a leptin receptor, ob-r. Cell. 1995;83:1263–1271. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chehab FF, Lim ME, Lu R. Correction of the sterility defect in homozygous obese female mice by treatment with the human recombinant leptin. Nat Genet. 1996;12:318–320. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barash IA, Cheung CC, Weigle DS, Ren H, Kabigting EB, Kuijper JL, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Leptin is a metabolic signal to the reproductive system. Endocrinology. 1996;137:3144–3147. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.7.8770941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farooqi IS, Matarese G, Lord GM, Keogh JM, Lawrence E, Agwu C, Sanna V, Jebb SA, Perna F, Fontana S, Lechler RI, DePaoli AM, O'Rahilly S. Beneficial effects of leptin on obesity, T cell hyporesponsiveness, and neuroendocrine/metabolic dysfunction of human congenital leptin deficiency. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1093–1103. doi: 10.1172/JCI15693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahima RS, Prabakaran D, Mantzoros C, Qu D, Lowell B, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS. Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature. 1996;382:250–252. doi: 10.1038/382250a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagatani S, Guthikonda P, Thompson RC, Tsukamura H, Maeda KI, Foster DL. Evidence for GnRH regulation by leptin: leptin administration prevents reduced pulsatile lh secretion during fasting. Neuroendocrinology. 1998;67:370–376. doi: 10.1159/000054335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez LC, Pinilla L, Tena-Sempere M, Aguilar E. Leptin(116–130) stimulates prolactin and luteinizing hormone secretion in fasted adult male rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1999;70:213–220. doi: 10.1159/000054479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welt CK, Chan JL, Bullen J, Murphy R, Smith P, DePaoli AM, Karalis A, Mantzoros CS. Recombinant human leptin in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:987–997. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiu J, Ogus S, Mounzih K, Ewart-Toland A, Chehab FF. Leptin-deficient mice backcrossed to the Balb/cj genetic background have reduced adiposity, enhanced fertility, normal body temperature, and severe diabetes. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3421–3425. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.8.8323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider JE. Energy balance and reproduction. Physiol Behav. 2004;81:289–317. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szymanski LA, Schneider JE, Friedman MI, Ji H, Kurose Y, Blache D, Rao A, Dunshea FR, Clarke IJ. Changes in insulin, glucose and ketone bodies, but not leptin or body fat content precede restoration of luteinising hormone secretion in ewes. J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19:449–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zamorano PL, Mahesh VB, De Sevilla LM, Chorich LP, Bhat GK, Brann DW. Expression and localization of the leptin receptor in endocrine and neuroendocrine tissues of the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1997;65:223–228. doi: 10.1159/000127276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Luca C, Kowalski TJ, Zhang Y, Elmquist JK, Lee C, Kilimann MW, Ludwig T, Liu SM, Chua SC., Jr Complete rescue of obesity, diabetes, and infertility in db/db mice by neuron-specific lepr-b transgenes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3484–3493. doi: 10.1172/JCI24059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magni P, Vettor R, Pagano C, Calcagno A, Beretta E, Messi E, Zanisi M, Martini L, Motta M. Expression of a leptin receptor in immortalized gonadotropin-releasing hormone-secreting neurons. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1581–1585. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.4.6622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quennell JH, Mulligan AC, Tups A, Liu X, Phipps SJ, Kemp CJ, Herbison AE, Grattan DR, Anderson GM. Leptin indirectly regulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal function. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2805–2812. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elmquist JK, Bjorbaek C, Ahima RS, Flier JS, Saper CB. Distributions of leptin receptor mrna isoforms in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395:535–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott MM, Lachey JL, Sternson SM, Lee CE, Elias CF, Friedman JM, Elmquist JK. Leptin targets in the mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2009;514:518–532. doi: 10.1002/cne.22025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caron E, Sachot C, Prevot V, Bouret SG. Distribution of leptin-sensitive cells in the postnatal and adult mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:459–476. doi: 10.1002/cne.22219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huo L, Maeng L, Bjorbaek C, Grill HJ. Leptin and the control of food intake: Neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract are activated by both gastric distension and leptin. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2189–2197. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cagampang FR, Maeda K, Ota K. Involvement of the gastric vagal nerve in the suppression of pulsatile luteinizing hormone release during acute fasting in rats. Endocrinology. 1992;130:3003–3006. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.5.1572309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murahashi K, Bucholtz DC, Nagatani S, Tsukahara S, Tsukamura H, Foster DL, Maeda KI. Suppression of luteinizing hormone pulses by restriction of glucose availability is mediated by sensors in the brain stem. Endocrinology. 1996;137:1171–1176. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.4.8625886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keen-Rhinehart E, Kalra SP, Kalra PS. AAV-mediated leptin receptor installation improves energy balance and the reproductive status of obese female koletsky rats. Peptides. 2005;26:2567–2578. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsukahara S, Tsukamura H, Foster DL, Maeda KI. Effect of corticotropin-releasing hormone antagonist on oestrogen-dependent glucoprivic suppression of luteinizing hormone secretion in female rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:101–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baskin DG, Breininger JF, Schwartz MW. Leptin receptor mRNA identifies a subpopulation of neuropeptide Y neurons activated by fasting in rat hypothalamus. Diabetes. 1999;48:828–833. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.4.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheung CC, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Proopiomelanocortin neurons are direct targets for leptin in the hypothalamus. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4489–4492. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith JT, Acohido BV, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Kiss-1 neurones are direct targets for leptin in the ob/ob mouse. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Celis ME. Release of LH in response to alpha-MSH administration. Acta Physiol Pharmacol Latinoam. 1985;35:281–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Granholm NH, Jeppesen KW, Japs RA. Progressive infertility in female lethal yellow mice (ay/a; strain c57bl/6j) J Reprod Fertil. 1986;76:279–287. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0760279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanobe H, Schiöth HB, Wikberg JES, Suda T. The melanocortin 4 receptor mediates leptin stimulation of luteinizing hormone and prolactin surges in steroid-primed ovariectomized rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:860–864. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huszar D, Lynch CA, Fairchild-Huntress V, Dunmore JH, Fang Q, Berkemeier LR, Gu W, Kesterson RA, Boston BA, Cone RD, Smith FJ, Campfield LA, Burn P, Lee F. Targeted disruption of the melanocortin-4 receptor results in obesity in mice. Cell. 1997;88:131–141. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hohmann JG, Teal TH, Clifton DK, Davis J, Hruby VJ, Han G, Steiner RA. Differential role of melanocortins in mediating leptin's central effects on feeding and reproduction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R50–R59. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.1.R50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balthasar N, Coppari R, McMinn J, Liu SM, Lee CE, Tang V, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Chua SC, Jr., Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Leptin receptor signaling in pomc neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2004;42:983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van de Wall E, Leshan R, Xu AW, Balthasar N, Coppari R, Liu SM, Jo YH, MacKenzie RG, Allison DB, Dun NJ, Elmquist J, Lowell BB, Barsh GS, de Luca C, Myers MG, Jr, Schwartz GJ, Chua SC., Jr Collective and individual functions of leptin receptor modulated neurons controlling metabolism and ingestion. Endocrinology. 2007;149:1773–1785. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill JW, Elias CF, Fukuda M, Williams KW, Berglund ED, Holland WL, Cho YR, Chuang JC, Xu Y, Choi M, Lauzon D, Lee CE, Coppari R, Richardson JA, Zigman JM, Chua S, Scherer PE, Lowell BB, Bruning JC, Elmquist JK. Direct insulin and leptin action on pro-opiomelanocortin neurons is required for normal glucose homeostasis and fertility. Cell Metab. 2010;11:286–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clark JT, Kalra PS, Kalra SP. Neuropeptide Y stimulates feeding but inhibits sexual behavior in rats. Obes Res. 1985;5:275–283. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wójcik-Gładysz A, Polkowska J. Neuropeptide Y – a neuromodulatory link between nutrition and reproduction at the central nervous system level. Reprod Biol. 2006;6:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erickson JC, Hollopeter G, Palmiter RD. Attenuation of the obesity syndrome of ob/ob mice by the loss of neuropeptide Y [see comments] Science. 1996;274:1704–1707. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Navarro VM, Fernandez-Fernandez R, Castellano JM, Roa J, Mayen A, Barreiro ML, Gaytan F, Aguilar E, Pinilla L, Dieguez C, Tena-Sempere M. Advanced vaginal opening and precocious activation of the reproductive axis by kiss-1 peptide, the endogenous ligand of gpr54. J Physiol. 2004;561:379–386. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tena-Sempere M. The roles of kisspeptins and G protein-coupled receptor-54 in pubertal development. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:442–447. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000236396.79580.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Roux N, Genin E, Carel JC, Matsuda F, Chaussain JL, Milgrom E. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the kiss1-derived peptide receptor gpr54. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10972–10976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834399100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Thresher RR, Acierno JS, Jr., Shagoury JK, Bo-Abbas Y, Kuohung W, Schwinof KM, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Dixon J, Kaiser UB, Slaugenhaupt SA, Gusella JF, O'Rahilly S, Carlton MB, Crowley WF, Jr, Aparicio SA, Colledge WH. The gpr54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1614–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colledge WH. Transgenic mouse models to study gpr54/kisspeptin physiology. Peptides. 2009;30:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castellano JM, Navarro VM, Fernandez-Fernandez R, Nogueiras R, Tovar S, Roa J, Vazquez MJ, Vigo E, Casanueva FF, Aguilar E, Pinilla L, Dieguez C, Tena-Sempere M. Changes in hypothalamic kiss-1 system and restoration of pubertal activation of the reproductive axis by kisspeptin in undernutrition. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3917–3925. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalamatianos T, Grimshaw SE, Poorun R, Hahn JD, Coen CW. Fasting reduces kiss-1 expression in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV): effects of fasting on the expression of kiss-1 and neuropeptide Y in the AVPV or arcuate nucleus of female rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:1089–1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luque RM, Kineman RD, Tena-Sempere M. Regulation of hypothalamic expression of kiss-1 and gpr54 genes by metabolic factors: analyses using mouse models and a cell line. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4601–4611. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Castellano JM, Navarro VM, Fernandez-Fernandez R, Roa J, Vigo E, Pineda R, Dieguez C, Aguilar E, Pinilla L, Tena-Sempere M. Expression of hypothalamic kiss-1 system and rescue of defective gonadotropic responses by kisspeptin in streptozotocin-induced diabetic male rats. Diabetes. 2006;55:2602–2610. doi: 10.2337/db05-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coppari R, Ichinose M, Lee CE, Pullen AE, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Tang V, Liu SM, Ludwig T, Chua SC, Jr, Lowell BB, Elmquist JK. The hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: a key site for mediating leptin's effects on glucose homeostasis and locomotor activity. Cell Metabolism. 2005;1:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Backholer K, Smith JT, Rao A, Pereira A, Iqbal J, Ogawa S, Li Q, Clarke IJ. Kisspeptin cells in the ewe brain respond to leptin and communicate with neuropeptide y and proopiomelanocortin cells. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2233–2243. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu L-Y, van den Pol AN. Kisspeptin directly excites anorexigenic proopiomelanocortin neurons but inhibits orexigenic neuropeptide Y cells by an indirect synaptic mechanism. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10205–10219. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2098-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davis PG, McEwen BS, Pfaff DW. Localized behavioral effects of tritiated estradiol implants in the ventromedial hypothalamus of female rats. Endocrinology. 1979;104:898–903. doi: 10.1210/endo-104-4-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simerly RB, Chang C, Muramatsu M, Swanson LW. Distribution of androgen and estrogen receptor mRNA-containing cells in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1990;294:76–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Merchenthaler I, Lane MV, Numan S, Dellovade TL. Distribution of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in the mouse central nervous system: In vivo autoradiographic and immunocytochemical analyses. J Comp Neurol. 2004;473:270–291. doi: 10.1002/cne.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim KW, Li S, Zhao H, Peng B, Tobet SA, Elmquist JK, Parker KL, Zhao L. CNS-specific ablation of steroidogenic factor 1 results in impaired female reproductive function. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1240–1250. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dhillon H, Zigman JM, Ye C, Lee CE, McGovern RA, Tang V, Kenny CD, Christiansen LM, White RD, Edelstein EA, Coppari R, Balthasar N, Cowley MA, Chua S, Jr, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Leptin directly activates sf1 neurons in the VMH, and this action by leptin is required for normal body-weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2006;49:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bingham NC, Anderson KK, Reuter AL, Stallings NR, Parker KL. Selective loss of leptin receptors in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus results in increased adiposity and a metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2138–2148. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elias CF, Kelly JF, Lee CE, Ahima RS, Drucker DJ, Saper CB, Elmquist JK. Chemical characterization of leptin-activated neurons in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2000;423:261–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leshan RL, Louis GW, Jo Y-H, Rhodes CJ, Munzberg H, Myers MG., Jr Direct innervation of GnRH neurons by metabolic- and sexual odorant-sensing leptin receptor neurons in the hypothalamic ventral premammillary nucleus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3138–3147. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0155-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Donato J, Jr, Silva RJ, Sita LV, Lee S, Lee C, Lacchini S, Bittencourt JC, Franci CR, Canteras NS, Elias CF. The ventral premammillary nucleus links fasting-induced changes in leptin levels and coordinated luteinizing hormone secretion. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5240–5250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0405-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simerly RB. Hormonal control of neuropeptide gene expression in sexually dimorphic olfactory pathways. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:104–110. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90186-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Canteras NS, Simerly RB, Swanson LW. Projections of the ventral premammillary nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1992;324:195–212. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rondini TA, Baddini SP, Sousa LF, Bittencourt JC, Elias CF. Hypothalamic cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript neurons project to areas expressing gonadotropin releasing hormone immunoreactivity and to the anteroventral periventricular nucleus in male and female rats. Neuroscience. 2004;125:735–748. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boehm U, Zou Z, Buck LB. Feedback loops link odor and pheromone signaling with reproduction. Cell. 2005;123:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kollack-Walker S, Newman SW. Mating and agonistic behavior produce different patterns of Fos immunolabeling in the male Syrian hamster brain. Neuroscience. 1995;66:721–736. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00563-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yokosuka M, Matsuoka M, Ohtani-Kaneko R, Iigo M, Hara M, Hirata K, Ichikawa M. Female-soiled bedding induced Fos immunoreactivity in the ventral part of the premammillary nucleus (PMV) of the male mouse. Physiol Behav. 1999;68:257–261. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cavalcante JC, Bittencourt JC, Elias CF. Female odors stimulate cart neurons in the ventral premammillary nucleus of male rats. Physiol Behav. 2006;88:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Donato J, Jr, Cavalcante JC, Silva RJ, Teixeira AS, Bittencourt JC, Elias CF. Male and female odors induce Fos expression in chemically defined neuronal population. Physiology & Behavior. 2010;99:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Coquelin A, Clancy AN, Macrides F, Noble EP, Gorski RA. Pheromonally induced release of luteinizing hormone in male mice: involvement of the vomeronasal system. J Neurosci. 1984;4:2230–2236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-09-02230.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Beltramino C, Taleisnik S. Release of LH in the female rat by olfactory stimuli: effect of the removal of the vomeronasal organs or lesioning of the accessory olfactory bulbs. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;36:53–58. doi: 10.1159/000123436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Beltramino C, Taleisnik S. Ventral premammillary nuclei mediate pheromonal-induced LH release stimuli in the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1985;41:119–124. doi: 10.1159/000124164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]