Abstract

The peptide hormone ghrelin mediates through action on its receptor, the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR), and is known to play an important role in a variety of metabolic functions including appetite stimulation, weight gain and suppression of insulin secretion. In light of the fact that obesity is one of the major health problems plaguing the modern society, the ghrelin signaling system continues to remain an important and attractive pharmacological target for the treatment of obesity. In vivo imaging of the GHSR could shed light on the mechanism by which ghrelin affects feeding behavior and thus offers a new therapeutic perspective for the development of effective treatments. Recently, a series of piperidine-substituted quinazolinone derivatives was reported to be selective and potent GHSR antagonists with high binding affinities. Described herein is the synthesis, in vitro and in vivo evaluation of (S)-6-(4-fluorophenoxy)-3-((1-[11C]methylpiperidin-3-yl)methyl)-2-o-tolylquinazolin-4(3H)-one ([11C]1), a potential PET radioligand for imaging GHSR.

Keywords: PET, ghrelin, 11C, growth hormone secretagogue receptor, GHSR

1. Introduction

Obesity and obesity related morbidities represent one of the most prevalent, chronic and fatal epidemics of the 21st century. While currently available therapies for obesity focus on weight reduction, treatments designed to specifically modulate the fundamental physiologic regulatory mechanism that controls food intake and energy balance may represent an attractive approach for the development of anti-obesity drugs.

Recently, there has been some evidence that ghrelin is a contributing factor in the development of diet-induced obesity.1-3 Ghrelin, a 28 amino acid acylated peptide hormone, is an endogenous ligand for the human growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR). First discovered in the stomach it is now known to be expressed in the hypothalamus and pituitary and in the peripheral tissues such as heart, lungs, spleen, adrenal and thyroid gland.4-7 While a substantial amount of data highlights the presence of ghrelin in the CNS8-11 and its role in appetite stimulation through a putative interaction with the receptor GHSR localized in the hypothalamus, the exact mechanism of action has yet to be determined. Monitoring the GHSR receptor in vivo and non-invasively with positron emission tomography (PET) would not only greatly improve our understanding of this receptor and its complex physiological role in appetite regulation but also aid the development of new pharmacological treatment for obesity and related conditions. A recent study presented several fluorine-bearing analogs of ghrelin that were synthesized as potential PET probes,12 but no GHSR in vivo imaging data have been published so far.

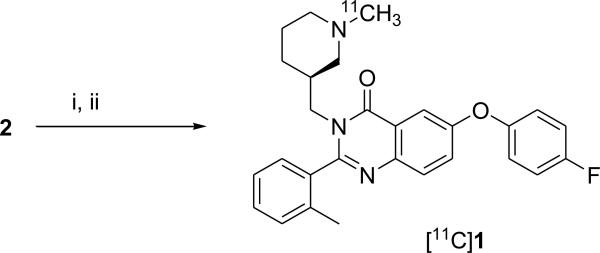

In this study we report the radiosynthesis of (S)-6-(4-fluorophenoxy)-3-((1-[11C]methylpiperidin-3-yl)methyl)-2-o-tolylquinazolin-4(3H)-one ([11C]1) (Scheme 2) and its in vitro and in vivo evaluation as a potential PET radioligand for imaging GHSR.

Scheme 2.

Radiosynthesis of [11C]1. Reagents and Conditions: (i) DMF, [11C]CH3OTf, 80°C; (ii) HPLC purification

2. Results and Discussions

The discovery of the orexigenic role of ghrelin1-3 has stimulated a substantial effort in synthesizing ghrelin antagonists that may interfere with body weight regulation. Industrial and academic medicinal chemists have developed a number of small molecule ghrelin antagonists.13 Recently, Bayer Pharmaceuticals disclosed a series of quinazolinone derivatives as orally available ghrelin receptor antagonists for treatment of diabetes and obesity.14 Two members of the series, racemic 6-(4-fluorophenoxy)-3-(piperidin-3-yl)methyl)-2-o-tolylquniazolin-4(3H)-one (2) and its N-isopropyl derivative exhibit high GHSR binding affinity (Ki = 0.9 and 0.47 nM, respectively).14 (S)-stereoisomers of this class appeared to exhibit better binding affinities than the corresponding (R)-isomers.14 We hypothesized that the (S)-stereoisomer of N-methyl derivative of 2 (compound 1, Scheme 1) should also manifest good GHSR binding affinity. Compound 1 is a small molecule with a molecular weight of 457.5 Da, which is within the conventional range (up to 500 Da) for passive blood-brain transport.15 The calculated physical-chemical properties of 1 (brain/blood ratio logBB = 0.45) suggest that 1 can penetrate the blood-brain barrier and its P-glycoprotein efflux probability (P-gl = 0.2) value is relatively low,16 and, thus, the radiolabeled [11C]1 may be suitable for PET imaging of cerebral GHSR.

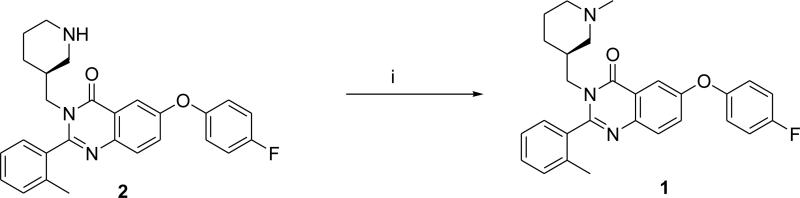

Scheme 1.

Syntheses of compound 1. Reagents and conditions: (i) HCOOH, H2CO(aq), reflux, 72%.

Chemistry

To test our hypothesis we synthesized 1 (Scheme 1) by reductive methylation of the desmethyl precursor 2.14 The structure of 1 was confirmed by NMR and high-resolution mass-spectroscopy analysis.

In vitro inhibition binding assays demonstrated that 1 binds at GHSR with a binding affinity Ki value of 22 nM.

Radiosynthesis of [11C]1 was performed by treating precursor 2 in DMF solution with [11C]methyl triflate at 80°C (Scheme 2). The radiochemical purity of [11C]1 after purification by HPLC and solid phase extraction was determined to be 99%. The final product contained only trace amount of impurities (acetonitrile < 12 ppm by GC analysis; precursor < 0.1 μg/batch by HPLC analysis). The total synthesis time was 35 min from the end-of-bombardment (EOB) with a non-decay-corrected radiochemical yield of 25% and specific radioactivity at the end of synthesis (EOS) of 8300±750 mCi/μmol (n = 4).

The identity of the radiotracer [11C]1 was confirmed by co-injection with non-radioactive reference compound 1 onto an analytical HPLC system (HPLC traces in supporting information). The final product [11C]1 was formulated as a sterile solution in saline with 8% alcohol.

In vivo experiments

Baseline experiments

The only known brain region with an elevated density of GHSR is the hypothalamus with a Bmax value of 56 fmol/mg protein or 0.7 fmol/mg tissue in humans17,18 and rats19, respectively. The radioactivity accumulation for [11C]1 was determined as %ID/g tissue in five regions of the CD1 mouse brain after intravenous injection of the radioligand (Table 1). GHSR is also present in pituitary, which is too small for the mouse dissection, and it was not studied in our work. Accumulation of [11C]1 radioactivity was relatively low in all brain regions known to have a low density of GHSR including cortex, cerebellum and hippocampus. By contrast, in the mouse hypothalamus there was a gradual increase of accumulation of [11C]1 radioactivity over the 90 min of the study (Table 1). The hypothalamus-to-cerebellum ratio increased steadily over the observation period reaching value of 1.6.

Table 1.

Brain regional distribution data for [11C]1 in CD1 mice. Data are the mean of %injected dose /g tissue ± SD (n=3)

| Brain Region | 10 min | 30 min | 60 min | 90 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebellum | 0.63±0.06 | 0.56±0.09 | 0.59±0.08 | 0.59±0.10 |

| Hypothalamus | 0.56±0.08 | 0.58±0.08 | 0.74±0.12 | 0.86±0.20 |

| Hippocampus | 0.60±0.13 | 0.59±0.09 | 0.71±0.08 | 0.65±0.12 |

| Cortex | 0.63±0.09 | 0.60±0.06 | 0.65±0.12 | 0.66±0.15 |

| Rest of brain | 0.54±0.07 | 0.57±0.06 | 0.62±0.02 | 0.54±0.08 |

A tracer dose (approximately 0.5 nmol/kg) of [11C]1 injected intravenously into CD1 mice (n=30) produced no observed pharmacological effects.

Blockade study

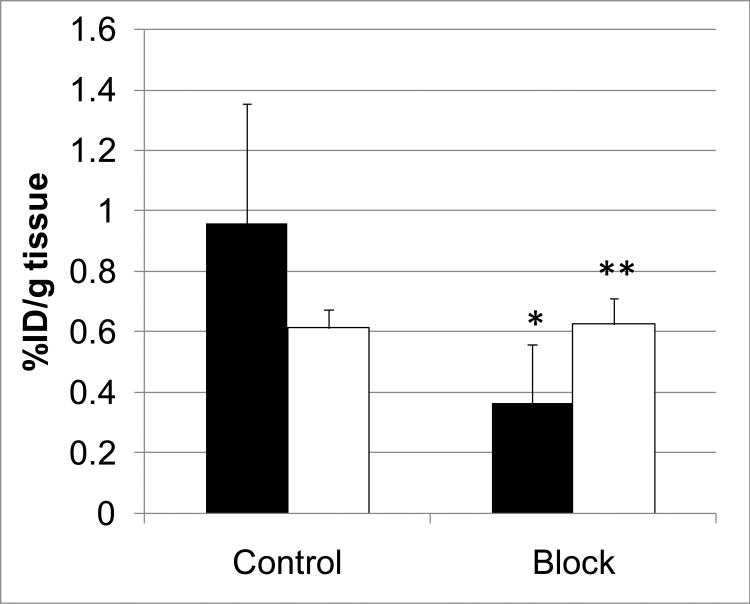

A blocking dose of GHSR antagonist 2 significantly inhibited [11C]1 binding in the hypothalamus at 90 min after administration of the radioligand suggesting that the binding in this region is specific and it is mediated by GHSR. As expected, the blockade in the rest of the brain was minimal (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of regional brain uptake of [11C]1 in mice at 90-min after injection in control and blocking experiments with 2 (1 mg/kg). Black bars – hypothalamus, white bars – the rest of brain. Data are mean ± SD (n=5). *P=0.04, significantly different from controls; **P>0.05, insignificantly different from controls (ANOVA single-factor analysis).

The regional brain distribution and blockade results suggest that [11C]1 is a radioligand with moderate specific cerebral uptake and relatively high non-specific binding. The low specific signal can be explained by the very low value of the GHSR density (Bmax, see above). The high non-specific binding can be attributed to the high lipophilicity of the radioligand [11C]1 (logD7.4 = 4.1 measured with the ACD log PDB program16) that is borderline for the conventional range for CNS radioligands (logD = 0 - 4). It would appear that a better GHSR radioligand may be needed for monkey and human brain PET studies. These future GHSR radioligands will likely require binding affinity in the picomolar range and a lower lipophilicity.

Body organs study

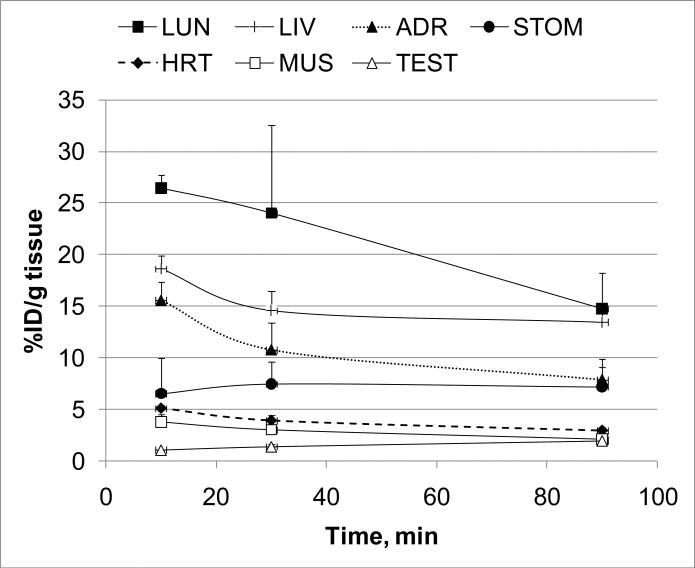

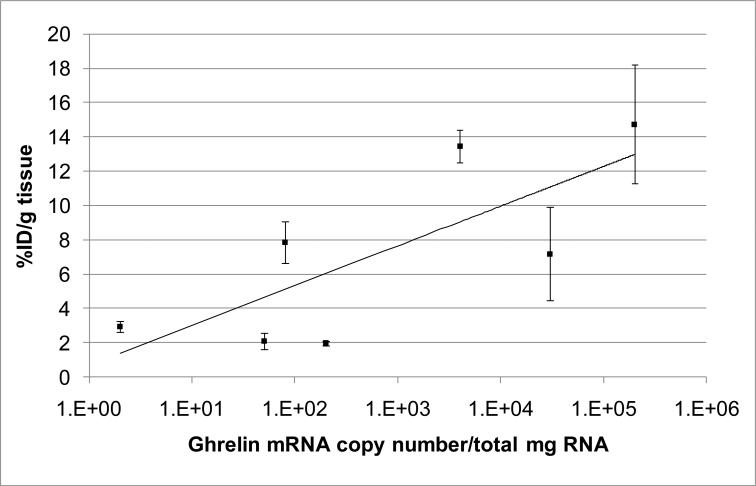

Knowing that the GHSR is widely distributed in the body and that there are available data on the ghrelin mRNA expression in the body tissues,6 it was possible to determine if the radioactivity distribution of [11C]1 matched the mRNA expression in the various body organs. Seven organs of CD1 mice with wide range of ghrelin expression were analyzed in dissection studies and the time-uptake curves for [11C]1 in these organs were generated (Figure 2). The lungs, liver and adrenal glands were the organs with the greatest uptake of radioactivity (Figure 2, Table 2). A blocking dose of GHSR antagonist 2 did not demonstrate a significant effect on the [11C]1 accumulation in the blood, heart, lungs, adrenal glands, testes, muscle and liver at 90 min after administration of the radioligand. This finding can be explained either by the absence of specific binding or by a receptor reserve that is too large6 for the blocker dose. The distribution of [11C]1 radioactivity correlated well (R2 = 0.58) with the expression of ghrelin RNA6 (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Time-uptake curves of [11C]1 in various body organs. Data are mean ± SD (n=5). Symbols: LUN – lungs, LIV – liver, ADR – adrenal gland, STOM – stomach, HRT – heart, MUS – muscle, TEST – testis.

Table 2.

Whole body distribution data for [11C]1 in CD1 mice, baseline and blocking experiments with 2 (1 mg/kg). Data are mean of %injected dose /g tissue ± SD (n=5)

| Baseline | Blocka | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 30 min | 90 min | 90 min | |

| Blood | 2.14±0.13 | 1.87±0.31 | 2.01±0.29 | 2.01±0.53 |

| Heart | 5.11±0.30 | 3.91±0.55 | 2.94±0.33 | 3.74±0.57 |

| Lung | 26.44±1.32 | 24.02±8.55 | 14.74±3.46 | 16.28±3.65 |

| Adrenals | 15.57±1.76 | 10.77±2.65 | 7.87±1.22 | 10.02±1.80 |

| Testis | 1.07±0.01 | 1.39±0.20 | 1.96±0.14 | 2.25±0.30 |

| Muscle | 3.79±0.68 | 3.02±0.45 | 2.09±0.47 | 2.22±0.79 |

| Liver | 18.63±1.29 | 14.60±1.89 | 13.46±0.97 | 14.77±1.02 |

P>0.05, insignificantly different from the 90 min baseline (ANOVA single-factor analysis).

Figure 3.

Correlation of distribution of [11C]1 radioactivity in CD1 mouse organs (mean %ID/g tissue ± SD (n=5)) with post-mortem ghrelin mRNA expression in human subjects.6

3. Materials and Methods

Chemistry

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) and used without further purification. Column flash chromatography was carried out using E. Merck silica gel 60F (230-400 mesh). Analytical thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on plastic sheets coated with silica gel 60 F254 (0.25mm thickness, Macherey-Nagel). 1H NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) spectra were recorded with a Varian-400 MHz in CDCl3. The spectra were acquired at 293 K. The chemical shifts were recorded on the ppm scale and were referenced to the internal standard trimethylsilane (TMS) at δH 0 ppm. Coupling constant (J) values were given in Hertz. Multiplicity was defined by s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), and m (multiplet).

(S)-6-(4-fluorophenoxy)-3-((1-methylpiperidin-3-yl)methyl)-2-o-tolylquniazolin-4(3H)-one (1) (Scheme 1)

(S)-6-(4-fluorophenoxy)-3-(piperidin-3-ylmethyl)-2-o-tolylquinazolin-4(3H)-one (2)14 (188 mg, 0.423 mmol) was heated at reflux in a 4 mL mixture of formaldehyde (37%) : formic acid (98%) (4:3) for 4 hours under a nitrogen atmosphere. After cooling the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was taken up in 10 ml of saturated aqueous sodium carbonate, and extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with aqueous sodium carbonate (5mL), dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated in vacuo. The crude compound was then purified by column chromatography on silica gel using hexane: ethyl acetate: methanol (50:45:5) as eluent to yield 0.112 mg (58%) as pale yellow solid, mp = 76-78 °C: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 7.74 (d, J = 2.93 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 2.19 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (dd, J = 8.79, 2.93 Hz, 1H), 7.37-7.42 (m, 2H), 7.29-7.35 (m, 2H), 7.07-7.10 (m, 4H), 4.12-4.19 (dd, J = 13.19, 7.33 Hz, 1H), 3.40-3.45 (m, 1H), 2.59 (t, J = 11.73 Hz, 2H), 2.37 (d, J = 12.46 Hz, 1H), 2.21 (s, 3H), 2.14 (d, J = 14.60 Hz, 3H), 1.70-1.88 (m, 2H), 1.37-1.60 (m, 2H), 1.19-1.25 (m, 1H), 0.75-0.92 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.1, 160.7, 157.0, 154.5, 151.9, 142.9, 135.6, 134.4, 130.9, 129.9, 129.3, 128.0, 126.2, 125.6, 121.2, 116.9, 112.8, 59.7, 55.9, 48.0, 46.9, 36.5, 27.7, 24.6, 19.2; HRMS (TOF-ESI) Calcd for C28H28FN3O2 (MH+): 458.2238. Found: 458.2241

Radiochemistry

The semi-preparative high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system consisted of a Waters model 610 pump, a Valco injector, a Varian Prostar 325 LC detector set to 254 nm, a Bioscan Flow-Count PMT radioactivity detector. Analytical HPLC was performed using a Varian Prostar 210 pump with a Prostar 410 Autosampler, a Varian Prostar 325 LC Detector set to 254 nm, a Bioscan Flow-Count PMT radioactivity detector. Gas chromatography (GC) was performed with a Varian 3800 GC and a FID detector. The GC column is a Phenomenex ZB-WAX 30 meter column, 0.25mm ID, 0.25 μm film. All HPLC and GC were recorded and analyzed with Varian Galaxie Chromatography Data System software (version 1.9.302.952). A dose calibrator (Capintec 15R) was used for all radioactivity measurements. [11C]Methyl iodide was prepared from 11CO2 using a Tracerlab FX MeI module (General Electric) and a PETtrace biomedical cyclotron (General Electric).

Synthesis of (S)-6-(4-fluorophenoxy)-3-((1-[11C]methylpiperidin-3-yl)methyl)-2-o-tolylquinazolin-4(3H)-one ([11C]1)

Precursor 214 (approx. 1 mg) was dissolved in 100 μL of anhydrous DMF and capped in a small V-vial. [11C]Methyl triflate was swept by argon flow into the vial. After the radioactivity reached a plateau, the vial was assayed in the dose calibrator and then heated at 80 °C for 5 min. Water (200 μL) was added and the solution was injected onto the semi-preparative HPLC column (Waters XBridge C-18 column, 10 × 150 mm; mobile phase: 410:590:1 v/v/v CH3CN/0.1 M ammonium formate/triethylamine, 12 mL/min). The retention time of normethyl precursor was 3.2 min. The product peak, having retention time of 7.9 min, was collected in 50 mL of HPLC water. The water solution was transferred through a Waters C-18 Oasis HLB Plus LP, 30 mg cartridge. The product was eluted with 1 mL ethanol into a vial and diluted with 10 mL of saline. The final product [11C]1 was then analyzed by analytical HPLC (Waters XBridge C-18, 4.6 × 100 mm, mobile phase: 410:590:1 v/v/v CH3CN / 0.1 M aqueous ammonium formate / triethylamine, 2.5 mL/min, tR=5.3 min) to determine the identity, radiochemical purity and the specific radioactivity at the end of synthesis.

In vitro binding assay

The in vitro inhibition binding assay of 1 was performed commercially by Ricerca Biosciences, (Concord, OH) under conditions similar to those previously published.17,20 This assay measures binding of [125I]ghrelin (human) to human GHSR. CHO-K1 cells stably transfected with a plasmid encoding human GHS receptors are used to prepare membranes in modified HEPES pH 7.4 buffer using standard techniques. A 0.25 mg aliquot of membrane was incubated with 0.03 nM [125I]ghrelin (human) for 60 minutes at 25°C. Non-specific binding was estimated in the presence of 0.1 mM ghrelin (human). Radioactivity trapped onto the filters was assessed using liquid scintillation spectrometry. The assays were done in duplicate at multiple concentrations of the test compounds. Binding assay results were analyzed using a one-site competition model, and IC50 curves were determined by a non-linear, least squares regression analysis using MathIQTM (ID Business Solutions Ltd., UK). The Ki value was calculated using the Cheng-Prusoff equation.21

In vivo experiments

Baseline dissection studies in mice

CD1 mice (all males, 23-28g) from the Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) were used in the animal experiments. The animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation at various times following injection of [11C]1 (0.1 mCi in 0.2 ml saline, specific radioactivity ~4000 mCi/μmol) into a lateral tail vein. The body organs and brain were rapidly removed and dissected on ice. The organs and brain regions of interest were weighed and their radioactivity content was determined in a γ–counter with a counting error below 3%. Aliquots of the injectate were used as standards and their radioactivity content was counted along with the tissue samples. The percent of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g tissue) was calculated. All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Johns Hopkins University.

Blocking dissection studies in mice

In vivo GHSR blocking studies were performed by subcutaneous administration of 1 mg/kg of 2 followed 15 min later by an intravenous injection of the radiotracer (0.1 mCi in 0.2 mL saline; specific radioactivity ~4000 mCi/μmol). Blocker 2 was dissolved in a vehicle solution (saline/alcohol 9:1) and administered in a volume of 0.1 mL. Control animals were injected with 0.1 mL of the vehicle solution. Ninety minutes after administration of the tracer, brain tissues were harvested, and the radioactivity content was determined. There were five animals in each, baseline and blockade group.

4. Conclusion

In summary, (S)-6-(4-fluorophenoxy)-3-((1-[11C]methylpiperidin-3-yl)methyl)-2-otolylquinazolin-4(3H)-one ([11C]1), a radioligand with GHSR binding affinity Ki = 22 nM, has been synthesized. In the mouse brain, [11C]1 specifically accumulated in the hypothalamus, a region with elevated density of GHSR, whereas the uptake of [11C]1 in all other brain regions with low densities of GHSR was non-specific. The whole body distribution of [11C]1 in CD1 mice matched well the expression of ghrelin mRNA in various body regions. However, blockade of [11C]1 with compound 2 in the whole body did not demonstrate a significant difference the distribution of radioactivity when compared to the baseline whole body study.

The results of cerebral distribution of [11C]1 in CD1 mice suggest that the radioligand imaging properties (specific binding = 38%) may not be sufficient for further brain studies in monkey and human subjects. Future development of cerebral GHSR radioligands should target a compound with picomolar binding affinity and moderate lipophilicity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Judy Buchanan for editorial assistance. This research was supported in part by the Division of Nuclear Medicine of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and by NIH Grants MH079017 and DA020777 (A.G.H.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wortley KE, del Rincon JP, Murray JD, Garcia K, Iida K, Thorner MO, Sleeman MW. Absence of ghrelin protects against early-onset obesity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3573–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI26003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Depoortere I. Targeting the ghrelin receptor to regulate food intake. Regul Pept. 2009;156:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tschop M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature. 2000;407:908–13. doi: 10.1038/35038090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–60. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mori K, Yoshimoto A, Takaya K, Hosoda K, Ariyasu H, Yahata K, Mukoyama M, Sugawara A, Hosoda H, Kojima M, Kangawa K, Nakao K. Kidney produces a novel acylated peptide, ghrelin. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:213–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnanapavan S, Kola B, Bustin SA, Morris DG, McGee P, Fairclough P, Bhattacharya S, Carpenter R, Grossman AB, Korbonits M. The tissue distribution of the mRNA of ghrelin and subtypes of its receptor, GHS-R, in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2988. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papotti M, Ghe C, Cassoni P, Catapano F, Deghenghi R, Ghigo E, Muccioli G. Growth hormone secretagogue binding sites in peripheral human tissues. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3803–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.10.6846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W, Zhao L, Lin TR, Chai B, Fan Y, Gantz I, Mulholland MW. Inhibition of adipogenesis by ghrelin. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2484–91. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horvath TL, Castaneda T, Tang-Christensen M, Pagotto U, Tschop MH. Ghrelin as a potential anti-obesity target. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:1383–95. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Date Y, Shimbara T, Koda S, Toshinai K, Ida T, Murakami N, Miyazato M, Kokame K, Ishizuka Y, Ishida Y, Kageyama H, Shioda S, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. Peripheral ghrelin transmits orexigenic signals through the noradrenergic pathway from the hindbrain to the hypothalamus. Cell Metab. 2006;4:323–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnold M, Mura A, Langhans W, Geary N. Gut vagal afferents are not necessary for the eating-stimulatory effect of intraperitoneally injected ghrelin in the rat. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11052–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2606-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosita D, Dewit MA, Luyt LG. Fluorine and rhenium substituted ghrelin analogues as potential imaging probes for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. J Med Chem. 2009;52:2196–203. doi: 10.1021/jm8014519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chollet C, Meyer K, Beck-Sickinger AG. Ghrelin-a novel generation of anti-obesity drug: design, pharmacomodulation and biological activity of ghrelin analogues. J Pept Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1002/psc.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudolph J, Esler WP, O'Connor S, Coish PD, Wickens PL, Brands M, Bierer DE, Bloomquist BT, Bondar G, Chen L, Chuang CY, Claus TH, Fathi Z, Fu W, Khire UR, Kristie JA, Liu XG, Lowe DB, McClure AC, Michels M, Ortiz AA, Ramsden PD, Schoenleber RW, Shelekhin TE, Vakalopoulos A, Tang W, Wang L, Yi L, Gardell SJ, Livingston JN, Sweet LJ, Bullock WH. Quinazolinone derivatives as orally available ghrelin receptor antagonists for the treatment of diabetes and obesity. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5202–16. doi: 10.1021/jm070071+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Advanced Chemistry Development/ADME Suite. Toronto, Canada: [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muccioli G, Papotti M, Locatelli V, Ghigo E, Deghenghi R. Binding of 125I-labeled ghrelin to membranes from human hypothalamus and pituitary gland. J Endocrinol Invest. 2001;24:RC7–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03343831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davenport AP, Bonner TI, Foord SM, Harmar AJ, Neubig RR, Pin J-P, Spedding M, Kojima M, Kangawa K. International union of pharmacology. LVI. Ghrelin receptor nomenclature, distribution, and function. Pharmacological Reviews. 2005;57:541–546. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrold JA, Dovey T, Cai XJ, Halford JC, Pinkney J. Autoradiographic analysis of ghrelin receptors in the rat hypothalamus. Brain Res. 2008;1196:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katugampola SD, Pallikaros Z, Davenport AP. [125I-His(9)]-ghrelin, a novel radioligand for localizing GHS orphan receptors in human and rat tissue: up-regulation of receptors with athersclerosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:143–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.