Abstract

Background Denmark decreased its tax on spirits by 45% on 1 October 2003. Shortly thereafter, on 1 January 2004, Sweden increased its import quotas of privately imported alcohol, allowing travellers to bring in much larger amounts of alcohol from other European Union countries. Although these changes were assumed to increase alcohol-related harm in Sweden, particularly among people living close to Denmark, analyses based on survey data collected before and after these changes have not supported this assumption. The present article tests whether alcohol-related harm in southern Sweden was affected by these changes by analysing other indicators of alcohol-related harm, e.g. harm recorded in different kinds of registers.

Methods Interrupted time-series analysis was performed with monthly data on cases of hospitalization due to acute alcohol poisoning, number of reported violent assaults and drunk driving for the years 2000–07 in southern Sweden using the northern parts of Sweden as a control and additionally controlling for two earlier major changes in quotas.

Results The findings were not consistent with respect to whether alcohol-related harm increased in southern Sweden after the decrease in Danish spirits tax and the increase in Swedish alcohol import quotas. On the one hand, an increase in acute alcohol poisonings was found, particularly in the 50–69 years age group, on the other hand, no increase was found in violent assaults and drunk driving.

Conclusions The present results raise important questions about the association between changes in availability and alcohol-related harms. More research using other methodological approaches and data is needed to obtain a comprehensive picture of what actually happened in southern Sweden.

Keywords: Alcohol-related harm, alcohol poisoning, violent assaults, drunk driving, tax change, private import quotas of alcohol

Introduction

Few countries have traditionally regarded alcohol as a public health issue to the same extent as the Nordic countries.1 As a result, the alcohol policies of particularly Sweden, Finland and Norway have been very restrictive, the goal being to limit not only alcohol consumption among problem drinkers but also the overall level of drinking. The most important tools for keeping alcohol consumption (total volume consumed) at a low level have been extensive restrictions on physical availability and high alcohol prices.2 To make these tools efficient, Sweden has also applied strict restrictions on the amount of alcohol that can be brought back privately from abroad, but these restrictions have been repealed since Sweden joined the European Union (EU) in 1995 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Changes in Swedish alcohol quotas from other EU countries since membership in the EU

| Time period | Sprits | Fortified wine | Table wine | Strong beer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 January 1995- | 1 L spirits or 3 L fortified wine | 5 L | 15 L | |

| 1 July 2000- | 1 L | 3 L | 20 L | 24 L |

| 1 January 2001- | 1 L | 6 L | 26 L | 32 L |

| 1 January 2002- | 2 L | 6 L | 26 L | 32 L |

| 1 January 2003- | 5 L | 6 L | 52 L | 64 L |

| 1 January 2004- (EU-quota) | Free import for personal use (indicative level: 10 L) | Free import for personal use (indicative level: 20 L) | Free import for personal use (indicative level: 90 L) | Free import for personal use (indicative level: 110 L) |

Source: Commissions of the Board 2000/44/EG, Ministry of Finance and the website of Swedish Customs (http://www.tullverket.se). Table was first published in Leifman and Gustafsson.3

Quotas refer to the amount (in litres) that can be brought into Sweden by travellers aged ≥20 years without any Swedish alcohol tax being paid.

With higher import quotas, raising alcohol taxes was no longer regarded as efficient owing to the risk of substitution effects, i.e. more alcohol would be purchased abroad instead. Furthermore, availability was increasing in practice, especially among residents in southern Sweden who live close to low-tax countries like Germany and Denmark, from which most of the privately imported alcohol comes.4 Earlier studies have also shown that especially southern Sweden has a high rate of private imports and that such imports account for almost half of all alcohol consumed in this part of Sweden.4 Therefore, it was assumed that the amount of alcohol consumed in this region would increase when Denmark, on 1 October 2003, decreased its tax on spirits by 45%—which was equivalent to a 25% decrease in the price of the cheaper brands of spirits—and when Sweden shortly thereafter, on 1 January 2004, increased its alcohol import quotas to the levels required by the EU (i.e. indicative levels of when import can be considered to be for one’s own use). Thus, although the decrease in price did not actually take place in Sweden, the already high market share for privately imported alcohol in southern Sweden and the short distance to Denmark suggested that the changes were equivalent to a price reduction in southern Sweden.

A recent study based on large repeated cross-sectional surveys was able to establish that travellers’ imports did increase substantially in southern Sweden in 2004.5 However, surveys measuring actual drinking did not find any increase in alcohol consumption or alcohol-related social problems. For instance, a comparison between 2003 and 2004 did not show any increase in volume of alcohol consumed in any region in Sweden, neither in the repeated cross-sectional samples for the total population nor in the longitudinal data.6 A study using a longer follow-up period did not change this conclusion, and no change was found in southern Sweden when data up until 2006 were analysed.7 In accordance with the results on consumption, alcohol-related social problems in southern Sweden did not increase as expected.8 Thus, the results from population surveys did not verify that alcohol consumption increased following these changes in alcohol policy.

As these unexpected results are based on survey data, with their limitations (i.e. in reaching heavy drinkers), further analyses on data less affected by such problems (i.e. various forms of register data) are warranted. In the present study, the number of hospital admissions for acute alcohol poisonings and the number of police-reported violent assaults and drunk-driving incidents were used to assess the impact of lower taxes in Denmark and higher Swedish import quotas. Analyses from other Nordic countries suggest that an analysis of this kind of register data can give new insights compared with studies based on survey data. In Finland, the raised quotas for private alcohol import were shown to have a great effect on heavier drinkers,9–11 among whom there was a striking increase in alcohol-related deaths between 2003 and 2004. Herttua, Mäkelä and Martikainen12 studied the effect of the reduction in price following the tax decrease in Finland in 2004 and also found an increase in alcohol-related mortality (mainly for chronic causes and particularly for liver diseases) after the change. In a study using interrupted time-series analysis, Koski et al.13 found an increase in alcohol-positive sudden deaths related to the tax cut on alcohol. Other sources of information in Finland have supported these findings as well, stating that substance abusers have been shown to be in poorer health after the changes9,14 and that intoxicated persons have been taken into custody more often.9,15 As for Denmark, time-series analysis performed on violent assaults and hospitalizations for acute alcohol intoxication from January 2000 through December 2005 showed an increase in hospitalizations due to acute alcohol intoxication after the Danish tax reduction in 2003 among individuals ≤15 years of age, but did not find such an increase in the total population or for violent assaults.16

For Sweden, no study using register data has yet been carried out to examine the effects on alcohol-related harm of the changes in private import quotas or the reduction in the Danish alcohol tax in 2003. According to a study of the relatively modest increase in travellers’ allowances of wine and beer in 1995, no increases in alcohol-related mortality, traffic accidents or reported criminal violence were found.17

The aim of this article is thus to study whether the abolishment of alcohol import quotas in 2004 and the Danish reduction in spirits tax 3 months earlier had any effect on alcohol-related harm in southern Sweden, using register data on alcohol poisonings, drunk driving and assaults as indicators of alcohol-related harm (more details are presented in the Methods section). As the hospitalization data on alcohol poisonings are available by age, we will also test the possibility of age-specific effects in order to replicate a similar study based on Danish data.16 Our starting point is that the effect may be stronger in age groups, mainly middle-aged people, known to travel and import most of the alcohol.18 Furthermore, a recent analysis of the impact of the increasing allowances and tax reduction in Finland suggested that the increase in alcohol-related mortality was basically seen in the age group 50–69 years.19

Methods

The selection of alcohol poisoning, drunk driving and assault as indicators of increasing harm in the analysis was justified by the following arguments. Naturally, all three indicators have a strong link to high alcohol consumption. Alcohol poisonings and drunk driving are by definition alcohol-related, and it is well established that a high proportion of perpetrators as well as victims of violent assaults are intoxicated.20,21 In addition, all three indicators have been found to have a positive association with sales at Systembolaget [the Swedish Alcohol Retail Monopoly stores] as well as with estimates of travellers’ alcohol imports in southern Sweden.23 Furthermore, data are available on a monthly basis, thus providing a sufficient number of data points for a meaningful time-series analysis as well as allowing us to come as close as possible in time to the specific changes. It was also considered important to have indicators that respond rapidly to an increase in drinking, thus ensuring that the problem of lagged effects will play a minor role.

Alcohol poisonings were measured as hospitalizations in which alcohol poisoning was the main or secondary diagnosis. These data are recorded in the Swedish Hospital Discharge Records and cover all public in-patient care in Sweden (for more information on this register, see http://www.sos.se/epc/english/ParEng.htm). The validity of the data is considered to be high, and the quality is continuously being evaluated. The selection of ICD codes (10th revision) that represent a case of alcohol poisoning was guided by the criteria set up by the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare and includes ‘Acute intoxication’ (F100), ‘Harmful use’ (F101) and ‘Toxic effect of alcohol’ (T51).

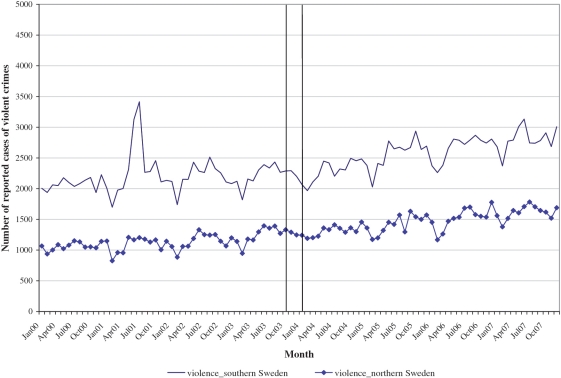

Statistics on alcohol-related crimes were collected from the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (BRÅ). Police-reported assaults include deadly violence, attempted murder, assaults and rape including aggravated cases. Data on police-reported drunk driving offences do not include driving while under the influence of drugs. It should be noted that some of these crimes do not lead to a sentence; this share accounts for only a few percentage points each year. As noted in the descriptive figure for violence (Figure 2), there was a peak in June to July 2001 in southern Sweden that was caused by riots in Gothenburg (southern Sweden) in relation to an EU meeting at this time. The series was therefore corrected using the linear interpolation command in Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 16.0, for these months.

Figure 2.

Descriptive figure over the trends in number of reported violent assaults in southern and northern Sweden (for south, this original series was corrected with linear interpolation). Vertical lines mark the tax change and the change in quotas. Figure covers the period January 2000 to December 2007

Monthly data covering the period January 2000 until December 2007 were analysed using interrupted time-series analysis, more specifically the technique developed by Box and Jenkins,24 often referred to as ARIMA models, in this case ARIMA impact analyses.25 Intervention components (dummy variables) were constructed to test whether there was any impact of the two interventions that could not be accounted for by normal fluctuations and long-term trends within the harm series. The first dummy took the value 0 before the tax change and 1 afterwards, and similarly the second dummy took the value 0 before the quota change and 1 afterwards. The final model controlled for changes in harm in northern Sweden as well as for two earlier changes in private import quotas of alcohol on 1 January 2002 and 2003 (Table 1) using dummies computed as for the other quota dummy.

In ARIMA modelling, data need to be stationary, which was assessed using the Dickey–Fuller test. Additionally, long-term trends should be removed prior to the analyses. Most series showed seasonal peaking (every 12th lag) with gradual attenuation, which indicates that the series requires seasonal differencing for stationarity.26 With a seasonal differencing of Yt, defined as Yt − Yt−12, the relationship between the changes in the same month but during the following years are analysed rather than the relationship between the raw series Yt and Yt + 1, one month compared with the following month during the same year. Furthermore, the method requires that the noise term (including other etiological factors) be allowed to have a temporal structure. The structure of the noise term (N) was modelled and estimated in terms of the autoregressive parameters (ARs) or moving average parameters (MAs). The model and noise specification are specified by the expression (p, d, q) (P, D, Q), the first parenthesis referring to the regular noise modelling and the second to the seasonality component. The order of the ARs and MAs is indicated by p and q, respectively, and the order of differencing is indicated by d. The corresponding symbols for the seasonal parameters are P, D and Q. The residuals of the estimated model should be white noise, which means that there is no structure of autocorrelation in the noise term. This was tested using the Box–Ljung Q-test.27

Other factors, in addition to the Danish tax cut and the increasing import quotas, are likely to affect both alcohol consumption and harm rates in southern Sweden, i.e. general trends in purchasing power and travelling habits in Sweden. There may also exist national trends in police enforcement and health policies that affected the selected harm indicators. Therefore, we used corresponding harm rates in northern Sweden as controls in our analysis, the assumption being that the long distance to the Danish and German borders would mean little effect of the reforms and that we would still capture the impact of other relevant factors. This idea was supported in separate analyses by site (without using a control site), where no effects of the interventions were found for northern Sweden (results not shown). It should be noted, however, that the findings for southern Sweden were little affected by the inclusion of northern Sweden as a control in the analysis and that the main results remained without this control variable (analysis not reported here).

The following specification was used in the final model:

where Ht symbolizes the harm indicator in the southern site at time t, i.e. by month. Ln signifies that the harm series are logarithmized. This means that the estimates of b1 − b5 can be expressed as change in percentage by applying the formula: 100×[exp(b) − 1]. T is the dummy variable for the Danish tax change in 2003, and Q1–Q3 represents the Swedish quota change in 2004 and the two previous quota changes in Sweden in 2002 and 2003. HNt is the harm indicator in northern Sweden. The estimates of N signify the noise term.

Results

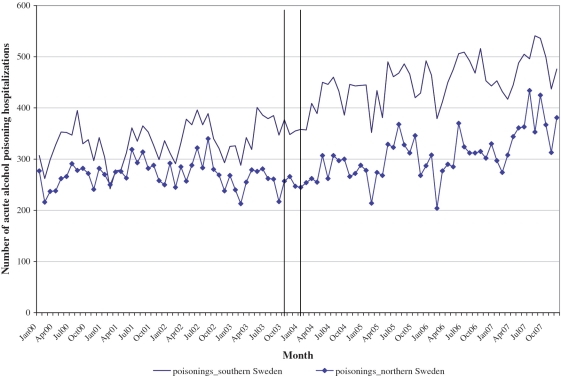

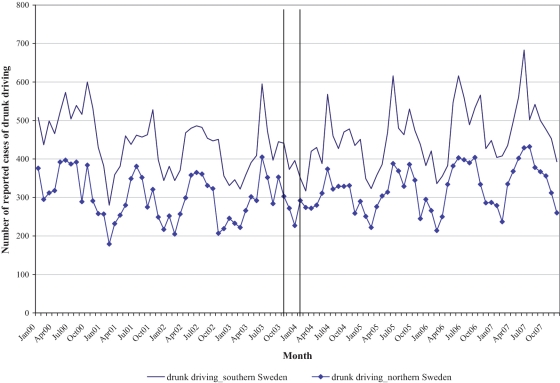

The graphs (Figures 1–3) reveal an increase in alcohol poisonings as well as in the number of reported violent crimes in both northern and southern Sweden, but no obvious increase in the number of drunk-driving cases for the period January 2000 until December 2007. With respect to alcohol poisonings, the development during the pre-intervention period was similar in both regions, but between 2003 and 2006, the rates increased more in southern Sweden than in the northern regions. In 2007, however, the rates were once again more similar.

Figure 1.

Descriptive figure over the trends in number of alcohol poisonings in southern and northern Sweden. Vertical lines mark the tax change and the change in quotas. Figure covers the period January 2000 to December 2007

Figure 3.

Descriptive figure over the trends in number of reported drunk driving in southern and northern Sweden. Vertical lines mark the tax change and the change in quotas. Figure covers the period January 2000 to December 2007

To test whether the two interventions had any effect on these kinds of harm, a series of interrupted time-series analyses were performed. The findings from the final model controlling for harm in northern Sweden and earlier quota changes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Estimated effects of Danish tax-cut in October 2003 and increased alcohol quotas in January 2004 on alcohol poisonings, violent crimes and drunk driving

| Output | Estimate | SE | P-value | 95% CI | Box-Young | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol poisoning | (1,0,0) (1,1,0,12) | 6.15 | 0.91 | ||||

| Tax change 03 | 0.031 | 0.044 | 0.480 | −0.055 | 0.118 | ||

| Quota change 04 | 0.100** | 0.039 | 0.009 | 0.025 | 0.176 | ||

| Violent crime | (0,0,0) (1,1,0,12) | 14.29 | 0.28 | ||||

| Tax change 03 | −0.037 | 0.031 | 0.237 | −0.098 | 0.024 | ||

| Quota change 04 | 0.025 | 0.026 | 0.347 | −0.027 | 0.076 | ||

| Drunk driving | (0,0,0) (0,1,1,12) | 10.80 | 0.55 | ||||

| Tax change 03 | −0.009 | 0.049 | 0.856 | −0.106 | 0.088 | ||

| Quota change 04 | 0.031 | 0.049 | 0.529 | −0.065 | 0.126 | ||

| Alcohol poisoninga | |||||||

| 10–19 years | (0,0,0) (0,1,1,12) | 7.92 | 0.79 | ||||

| Tax change 03 | −0.000 | 0.145 | 0.998 | −0.285 | 0.284 | ||

| Quota change 04 | 0.138 | 0.144 | 0.338 | −0.144 | 0.421 | ||

| 20–29 years | (0,0,0) | 14.08 | 0.30 | ||||

| Tax change 03 | −0.076 | 0.182 | 0.675 | −0.434 | 0.281 | ||

| Quota change 04 | 0.121 | 0.177 | 0.493 | −0.226 | 0.469 | ||

| 30–49 years | (0,0,1) (1,1,0,12) | 17.23 | 0.14 | ||||

| Tax change 03 | 0.106 | 0.092 | 0.249 | −0.074 | 0.285 | ||

| Quota change 04 | 0.050 | 0.085 | 0.556 | −0.117 | 0.218 | ||

| 50–69 years | (0,0,0) (1,1,0,12) | 11.17 | 0.51 | ||||

| Tax change 03 | 0.013 | 0.062 | 0.839 | −0.110 | 0.135 | ||

| Quota change 04 | 0.122* | 0.058 | 0.037 | 0.008 | 0.236 | ||

| ≥70 years | (1,0,0) | 13.45 | 0.34 | ||||

| Tax change 03 | 0.286 | 0.355 | 0.421 | −0.411 | 0.982 | ||

| Quota change 04 | 0.011 | 0.349 | 0.975 | −0.672 | 0.694 | ||

CI: confidence interval; SE: standard error. Semi-logarithmic ARIMA models estimated on monthly data January 2000 to December 2007 for southern Sweden, controlling for changes in the harm rates in northern Sweden and quota changes of 2002 and 2003.

aFor alcohol poisonings, trends are also estimated by age.

*P < 0.05.

**P < 0.01.

The only effect revealed in all these ARIMA models was the effect of the traveller’s allowance change in 2004 on alcohol poisonings in southern Sweden. After applying the conversion formula to the estimate of 0.10 in the final model, we note that the intervention effect of the increased import quotas was followed by a 10.5% increase in the number of hospitalizations due to alcohol poisoning. However, the tax decrease in Denmark was not shown to have affected the different kinds of harm, and none of the interventions had any impact on violent crime or drunk driving. A further analysis showed that there was a strong correlation (Rxy = 0.76) between the estimates of the quota change and the tax decrease in southern Sweden, which produced uncertain results when both variables were estimated in the same model. Thus, we cannot rule out that the tax decrease, too, was part of the effect found for the increase in private import quotas of alcohol.

An increase in alcohol poisonings due to the change in the traveller’s allowance in 2004 was not observed among all age groups (Table 2), but was in fact only observed among those aged 50–69 years. The changes in quotas implied a 13% increase in alcohol poisonings in southern Sweden in this group.

All models were satisfactory with respect to the residual autocorrelation; thus the auto correlations were close to zero, indicating that the time series are random (white noise). It should be noted that the semi-logarithmic model specification applied here assumes multiplicative effects of the two policy changes. As this may not necessarily be the case, the analyses were also performed using linear models, which, however, did not change the outcome.

Discussion

The Danish decrease in spirits tax in 2003 and the abolishment of Swedish alcohol import quotas on alcohol in 2004 suggested that alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm would increase, especially in the southern parts of Sweden. This expectation has not been verified in previous studies using survey data, and the aim of the present study was to investigate the same issue by analysing various register data using an interrupted time-series approach. Hospitalization for acute alcohol poisoning and police-reported cases of drunk driving and violent assaults were used as indicators of alcohol-related harm.

Overall, the results of the present analyses did not allow for any definite conclusion as to whether alcohol-related harm increased in southern Sweden. On the one hand, an increase in acute alcohol poisonings was found after the increase in import quotas, particularly among those aged 50–69 years, but on the other hand, no increase was found in violent assaults or in drunk driving. Thus, the findings with respect to assaults and drunk driving supported previous findings based on survey data and the conclusion that problems had not increased, whereas the increase in alcohol-related harm (alcohol poisonings) in southern Sweden suggests that some problems may have worsened, at least among middle-aged people in southern Sweden.

One interpretation of the results is simply that some problems increased whereas some did not and that these harm indicators measure specific problems rather than alcohol-related harm in general. Thus, drunk driving and alcohol-related violence were not affected by the increase in travellers’ imports allowances, because these crimes are primarily committed by younger people who are less affected by lower import quotas. Only about 10 and 20% of the perpetrators of assault and drunk drivers are >50 years of age, whereas the corresponding figure for those hospitalized for alcohol poisoning is ∼50% (according to data from the Swedish Council for Crime Prevention). Thus, the finding that the travellers’ imports of alcohol are most common among people >50 years of age18 could explain some part of the difference, although further studies are needed to test this idea. It is also worth noting that there are some similarities with Finnish experiences related to their abolishment of import quotas and reduction of alcohol taxes in 2004. An analysis by Herttua19 found no impact on assaults after the changes, but an increase in alcohol-related hospitalizations, which was largest in the age group 50–69 years. Thus the increases in both countries can be linked to older heavy drinkers, who are known to be less well represented in surveys. Our findings also have some similarities with a study from Denmark using the same time-series approach. This study examined changes in alcohol-related harm in Denmark between 2003 and 2005 after changes in alcohol policies were introduced and found no increase in violent assaults. On the other hand, an increase in alcohol poisonings was revealed but only among those aged ≤15 years.16 Although the overall findings from these countries indicate an increase in harms, the results vary by subgroup, suggesting that the effects of this kind of increase in availability may be influenced by cultural differences and that findings for one country should not automatically be generalized to other countries. In this specific case, it is also important to consider that the Danish and Finnish changes were domestic, whereas in Sweden a trip abroad was required to take advantage of the new possibilities to buy cheaper alcohol.

Naturally, one major limitation of this kind of study, which uses a quasi-experimental design, is that the intervention and control groups have not been randomly selected. Thus, there may have been large systematic initial differences between southern and northern Sweden, meaning that the latter was a poor control site. The higher level of drinking and harm in the southern site are two possible examples. However, in the present study, we had to identify a region affected to a lesser degree by the major interventions of interest: the Danish tax decrease and the abolishment of import quotas. Although certainly not a perfect control area, the northern parts of Sweden were the best choice available for fulfilling these criteria and, as previously mentioned, no effect on harm in northern Sweden could be established in relation to these reforms.

In conclusion, because previous survey analyses have not revealed any increase in alcohol-related problems in southern Sweden, the present findings highlight the importance of using various data sources when studying policy changes and their potential impacts on alcohol-related harm. It also stresses the fact that various data sources are able to cover different segments of the population and that choosing one over the other may result in missing an existing effect. Additionally, the results presented here raise important questions about the association between changes in availability and alcohol-related harms in Sweden today.

Funding

US National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [R01 AA014879], as part of the study Effects of Major Changes in Alcohol Availability.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

KEY MESSAGES.

When Denmark decreased their tax on spirits and Sweden shortly thereafter abolished its private import quotas on alcohol to unlimited levels if it was for private consumption, it was assumed that people in the southern parts of Sweden would increase their imports of alcohol. Because private imports already corresponded to ∼50% of the total alcohol consumption among Swedes in the south, it was expected that per capita alcohol consumption in this region would increase, and thus also the alcohol-related harms.

The present results in this study did not allow for any definite conclusion regarding whether alcohol-related harm increased in southern Sweden. Using an interrupted time-series analysis, an increase in alcohol poisonings was found in relation to the repeal of the alcohol import quotas, but not in relation to the Danish tax decrease. Similarly, no increase was found in violent assaults or drunk driving.

It is concluded that the results raise important questions about the association between changes in availability and alcohol-related harms in Sweden today.

References

- 1.Room R. The idea of alcohol policy. NAT (Nordisk alcohol and narkotikatidskrift) [Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs] 1999;16((English supplement)):7–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity: Research and Public Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leifman H, Gustafsson N-K. A Study of the Alcohol Consumption in the Swedish Population at the Beginning of the 21st Century Research Report No. 11. Stockholm: SoRAD, SU; 2003. A toast for the new millennium. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramstedt M, Axelsson Sohlberg T, Engdahl B, Svensson J. Research Report no. 54. Stockholm: SoRAD, SU; 2009. Talk about/figures of alcohol 2008: a statistical yearly report from the monitoring study. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramstedt M, Gustafsson N-K. Increasing travellers’ allowances in Sweden—how did it affect travellers’ imports and Systembolaget’s sales? NAT (Nordisk alcohol and narkotikatidskrift) [Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs] 2009;26:165–76. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mäkelä P, Bloomfield K, Gustafsson N-K, Huhtanen P, Room R. Changes in volume of drinking after changes in alcohol taxes and traveller’s allowances: results from a panel study. Addiction. 2007;103:181–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustafsson N-K. Alcohol consumption in southern Sweden after major decreases in Danish spirits tax and increases in traveller’s quotas. Eur Addict Res. 2010;16:152–61. doi: 10.1159/000314358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloomfield K, Wicki M, Gustafsson N-K, Mäkelä P, Room R. Changes in alcohol-related problems after alcohol policy changes in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:32–40. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mustonen H, Mäkelä P, Huhtanen P. People are buying and importing more alcohol than ever before. Where is it all going? Drugs Educ Prev Pol. 2007;14:513–27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mäkelä P, Österberg E. The use of alcohol is increasing—does well-being increase? In: Kautto M, editor. The Wellbeing of the Finns 2006. Helsinki, Finland: STAKES; 2006. pp. 306–28. (in Finnish) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mäkelä P, Österberg E. Cheap pleasures? What are the consequences? Tiimi. 2006;2:4–6. (in Finnish) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herttua K, Mäkelä P, Martikainen P. Changes in alcohol-related mortality and its socioeconomic differences after a large reduction in alcohol prices: a natural experiment based on register data. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1110–18. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koski A, Sirén R, Vuori E, Poikolainen K. Alcohol tax cuts and increase in alcohol-positive sudden deaths—a time-series intervention analysis. Addiction. 2007;102:362–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murto L, Niemelä J. The prevention of alcohol-related harms demands fast interventions. Helsingin Sanomat. 7 March 2005 (in Finnish) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noponen T. Communications of Police College of Finland 43. Helsinki, Finland: Poliisiammattikorkeakoulu; 2005. Alcohol-related arrests made by the police and the persons taken into custody in Helsinki. (in Finnish) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bloomfield K, Rossow I, Norström T. Changes in alcohol-related harm after alcohol policy changes in Denmark. Eur Addict Res. 2009;15:224–31. doi: 10.1159/000239416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norström T. Cross-border trading of alcohol in southern Sweden—substitution or addition? In: Holder HD, editor. Sweden and the European Union: Changes in National Alcohol Policy and their Consequences. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell International; 2000. pp. 221–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Svensson J. Travellers’ alcohol imports to Sweden at the beginning of the 21st century. NAT (Nordisk alcohol and narkotikatidskrift) [Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs] 2009;26:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herttua K. The Effects of the 2004 Reduction in the Price of Alcohol on Alcohol-Related Harm in Finland: A Natural Experiment Based on Register Data. Finnish Yearbook of Population Research No. 45, Supplement. Helsinki, Finland: Population Research Institute, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossow I, Pernanen K, Rehm J. Alcohol, suicide and violence. In: Klingemann H, Gmel G, editors. Mapping the Social Consequences of Alcohol Consumption. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irlander Å, Westfelt L. Nationella trygghetsundersökningen NTU 2009: Om utsatthet, trygghet och förtroende Brå Rapport 2010:02 [the National Study of Security NTU 2009 About vulnerableness, safety and fiduciary] Stockholm: Brå (The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention) 2010 p. 34 (in Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pernanen K, Cousineau M-M, Brochu S, Dun F. Proportions of Crimes Associated with Alcohol and Other Drugs in Canada. Canada: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/200/300/ccsa-cclat/proportions_crimes-e/crime2002.pdf (20 July 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norström T, Ramstedt M. Unregistered alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm in Sweden, 2001–2005. NAD (Nordic Council for Alcohol and Drug Research) 2008;25:101–14. (in Finnish) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Box GEP, Jenkins GM. Time-series Analysis: Forecasting and Control. London: Holdens Day, Inc.; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDowall D, McCleary R, Meidinger EE, Hay RA. Interrupted Time-series Analysis, Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. Beverly Hills and London: Sage Publications; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaffee R, McGee M. Time Series Analysis and Forecasting with Applications of SAS and SPSS. California: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ljung GM, Box GEP. Measure of lack of fit in time-series models. Biometrika. 1978;65:297–303. [Google Scholar]