Abstract

Background To investigate lifetime history of interpersonal abuse and risk of pre-natal depression in socio-economically distinct populations in the same city.

Methods We examined associations of physical and sexual abuse with the risk of pre-natal depression in two cohorts in the Boston area, including 2128 participants recruited from a large urban- and suburban-managed care organization (Project Viva) and 1509 participants recruited primarily from urban community health centres (Project ACCESS). Protocols for the studies were designed in parallel to allow us to merge data to enhance ethnic and socio-economic diversity in the combined sample. In mid-pregnancy, the Personal Safety Questionnaire and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) were administered in both cohorts. An EPDS score ≥13 indicated probable pre-natal depression. Logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) of pre-natal depression associated with lifetime abuse history.

Results Project ACCESS participants were twice as likely as Project Viva participants to report symptoms consistent with pre-natal depression: 22% of Project ACCESS participants had EPDS scores ≥13, compared with 11% of Project Viva participants. Fifty-seven percent of women in ACCESS and 46% in Viva reported lifetime physical and/or sexual abuse. In merged analysis, women reporting lifetime physical or sexual abuse had an OR for mid-pregnancy depression of 1.63 [95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.29–2.07], adjusted for age and race/ethnicity. Lifetime histories of physical abuse [OR 1.48 (95% CI 1.15–1.90)] and sexual abuse [OR 1.68 (95% CI 1.24–2.28)] were independently associated with pre-natal depression. When child/teen, pre-pregnancy adult and pregnancy life periods were considered simultaneously, abuse in childhood was independently associated with an OR of 1.23 (95% CI 1.00–1.59), pre-pregnancy adult abuse with an OR of 1.70 (95% CI 1.31–2.21) and abuse during pregnancy with an OR of 1.77 (95% CI 1.14–2.74). Further adjustment for childhood socio-economic position made no material difference, and there were no clear interactions between abuse and adult socio-economic position.

Conclusions Physical and sexual abuse histories were positively associated with pre-natal depression in two economically and ethnically distinct populations. Stronger associations with recent abuse may indicate that the association of abuse with depression wanes with time or may result from less accurate recall of remote events.

Keywords: Depression, pregnancy, violence, pre-natal care, adult survivors of child abuse, partner abuse, spouse abuse

Introduction

Between 10% and 20% of the women experience depression during pregnancy.1,2 Given its high prevalence and lingering questions regarding the safety and acceptability of anti-depressants during pregnancy,3 it is important to identify preventable risk factors associated with depression during pregnancy.

Violent abuse, both past and present, is associated with major depression in non-pregnant women.4–6 Intimate partner violence during pregnancy is strongly associated with pre-natal depression.7 Some studies have reported heightened depression symptoms among women who experienced pre-pregnancy abuse, including victimization in childhood and adolescence.8–15 However, almost no studies have examined the specific risks of pre-adult abuse experiences after accounting for the adult abuse experiences with which early abuse is unfortunately associated.10 If abuse isolated to early life is associated with later risk of depression in pregnancy, then treatment of abused girls may prevent pre-natal depression, and pre-natal screening for a history of early abuse may identify newly pregnant women at high risk of depression. The only study to simultaneously examine child and adult abuse is that of Holzman and colleagues,10 who reported that abuse during childhood was less predictive of pre-natal depression scores than abuse during adulthood, with highest depression scores among women who experienced abuse in both time periods.

In the Holzman study, a history of abuse was particularly powerful among disadvantaged women,10 a finding which prompts replication in a large sample with a broad range of socio-economic exposure. Most studies of life-course abuse and pre-natal depression have included fewer than 400 participants,8,9,11,12,15,16 or have been recruited solely from low-income populations,8,9,11,13,14 limiting their ability to examine effect modification by socio-economic position.

We sought to add to the literature by separately examining the associations of lifetime physical and sexual abuse with pre-natal depression, accounting for recency of abuse experiences. We further sought to investigate whether histories of sexual and physical abuse were similarly associated with pre-natal depression in two socio-economically distinct cohorts in Boston.

Methods

Study populations

We examined associations of lifetime experiences of abuse with the risk of pre-natal depression in two large cohorts of pregnant women: Project Viva and Project ACCESS (Asthma Coalition on Community, Environment and Social Stress). Both studies are prospective observational cohorts designed to examine associations of pre-natal environmental exposures with pregnancy and childhood outcomes. Project Viva was designed to examine dietary, hormonal and psychosocial predictors of pregnancy outcomes and child health. Project ACCESS was designed to study interactive effects of early life stress and other physical environmental factors on urban childhood asthma risk. We took advantage of the fact that both cohorts were launched at roughly the same time in the Boston area, designing the studies in tandem with complementary protocols and similar survey instruments so that we could pool data to examine health effects across a broader range of socio-economic position and racial/ethnic diversity. At mid-pregnancy in both cohorts, depression symptomatology was assessed by using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and abuse history was measured by the Personal Safety Questionnaire.

Project Viva

Project Viva participants were recruited between 1999 and 2002 at their first pre-natal visit to one of eight obstetric practices of Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates, a large urban and suburban group practice in the Boston area. Most patients in this system are privately insured. Eligible women obtained their first pre-natal visit before 22 weeks of gestation, had singleton pregnancies, were able to complete interviews and questionnaires in English and planned to carry their pregnancy to term and to deliver within the health-care system. The obstetrics clinical staff included a flier about Project Viva in informational packets sent to newly pregnant patients. After the first pre-natal appointment, a study research assistant met the patient to inform her of the aims and procedures of the study, to ensure that inclusion criteria were met, to obtain informed consent and to provide the participant with the initial questionnaire. The Project Viva study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care.

Project ACCESS

Project ACCESS recruitment has been ongoing since August 2001, enrolling women receiving pre-natal care at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston Medical Center, three urban community health centres and pregnant women attending Women, Infants and Children (WIC) programmes associated with the health centres in the Boston metropolitan area and surrounding suburbs. For this analysis, we included women who had delivered before September 2008. Women who did not speak either English or Spanish were excluded. Women receiving pre-natal care were approached by trained research assistants. Written informed consent was obtained in the subject’s primary language. The study was approved by the human studies committees at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Boston Medical Center.

Measures

Abuse exposure assessment

We developed the Personal Safety Questionnaire (PSQ) for use in both cohorts based on the Conflicts Tactics Scales.17 For both cohorts, participants were met by research assistants in mid-pregnancy, who administered the PSQ in a private area of the clinic, either as an interview or as a written questionnaire, according to the participant’s preference. The PSQ queries the occurrence of specific incidents, including: ‘push, grab or shove you’, ‘kick, bite or punch you’, ‘hit with something that hurt your body’, ‘choke or burn you’, ‘force you to have sexual activities’ and ‘physically attack you in some other way’. We enhanced the original Conflicts Tactics Scales questions by separately assessing incidents occurring in childhood (up to the age of 11 years by ‘anyone who was at least 5 years older than you’), adolescence (aged 12–17 years), adulthood (aged 18 years until this pregnancy) and pregnancy. This enhancement allowed us to examine both the ‘type’ of abuse (physical or sexual) and ‘timing’ of abuse over life periods.

Depression symptoms assessment

Both Project Viva and Project ACCESS administered the 10-item EPDS during mid-pregnancy. Project Viva participants completed the EPDS as part of a longer mid-pregnancy questionnaire, and Project ACCESS participants as part of a mid-pregnancy interview. Validation of the EPDS, which measures past week symptoms, against diagnostic clinical interviews indicated a specificity of 78% and a sensitivity of 86% for major depression.18 The total score ranges from 0 to 30; a score of at least 13 is commonly used to indicate probable depression in large cohort studies.19–21 We used the cut-off point of ≥13 to indicate probable major or minor pre-natal depression, consistent with previous work in Project Viva22,23 and in other large cohorts that collected EPDS data in both the pre-natal and postpartum periods.28 We also ran the analysis using an EPDS cut-off point of ≥15 to indicate pre-natal depression, as some authors prefer that cut-off point.19,24 As results for the merged cohort analysis were largely the same with both cut-off points, we report here only results for the cut-off point of ≥13. The EPDS is a screening tool that measures probable depression, and is not a clinical diagnosis of depression; however, to be succinct, we refer to an EPDS score ≥13 as ‘pre-natal depression’.

In both Project Viva and ACCESS, data were collected on age, race/ethnicity, household income, maternal education, parity, smoking and marital status. Participants were also asked their country of birth. In addition, study participants in Project Viva were asked about their parents’ highest level of educational attainment. In Project ACCESS, participants were asked whether their parents owned their home during the participant’s childhood. Parents’ highest level of educational attainment was modelled in Project Viva and home ownership during childhood was modelled in Project ACCESS to control for confounding by childhood socio-economic position.

Population for analysis

Project Viva enrolled 64% of invited women; of the 2341 eligible participants, 9% withdrew (n = 195) or were lost to follow-up (n = 18), leaving 2128 women with live births. Project ACCESS administered a screening questionnaire to 1737 women, of whom 1613 (93%) continued into the longitudinal study. We excluded 104 women (6%) from Project ACCESS who were lacking all data regarding abuse, depression and other covariates collected after the brief screening interview. The total combined cohort consisted of 3637 study participants.

Statistical analysis

We used the Amelia II multiple imputation programme to produce complete data sets for Project Viva and for Project ACCESS.25,26 All imputed variables were considered ordinal or nominal. In Project Viva, we imputed a set of variables, including abuse history (n = 400 missing data), pre-natal depression symptoms (n = 577) and age or race (n = 5). In Project ACCESS, we imputed abuse history (n = 548), pre-natal depression symptoms (n = 559) and age or race (n = 7). Missing data in education, income, marital status, immigrant status, smoking and childhood socio-economic position were also imputed. After imputation, these data sets were combined and all analyses were performed using Proc LOGISTIC and Proc MI ANALYZE with 20 replications in Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).27 We also conducted a ‘complete case’ analysis, including only those participants who had complete data. We used logistic regression to estimate OR of pre-natal depression associated with abuse exposures. We present as our main analyses age- and race-adjusted models. As adjustment for childhood socio-economic position (parental education in Project Viva and parental home ownership in Project ACCESS) did not materially affect the associations between abuse and pre-natal depression, we did not consider these variables to be confounders. As depression risk factors, such as adult education, smoking, marital status or income, are likely to have been partially determined by pre-adult abuse experiences, these factors are potential intermediates between early abuse and adult depression. We provide secondary analyses adjusted for these factors to allow readers to gauge the associations of abuse with depression independent of these potential intermediates.

We first examined associations of abuse and pre-natal depression in each cohort separately, then tested whether there were interactions of cohort membership, maternal education, childhood socio-economic position, race/ethnicity or immigration status with abuse exposure by including multiplicative interaction terms. We repeated the abuse and education interaction analysis in models excluding 276 participants who were <20 years old, and found similar results (data not reported).

Results

The socio-demographic characteristics of the Viva and ACCESS cohorts are described in the first two columns of Table 1. Project Viva had a largely White, college-educated population that comprised predominantly of married women aged >30 years, who tended to be US-born and to have annual household incomes over $70 000. In contrast, most Project ACCESS participants were aged <30 years, immigrants and of Latino or Black heritage. Although one-third of Project ACCESS participants continued education beyond high school, 43% were unpartnered and the majority lived in households earning less than $20 000 per year.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and prevalence of abuse in Project Viva and Project ACCESSa

| Cohort characteristics |

Prevalence of abuse: Project Vivab |

Prevalence of abuse: Project ACCESSb |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project Vivac | Project ACCESSd | Never abuse | Ever any abuse | Ever physical abuse | Ever sexual abuse | Never abuse | Ever any abuse | Ever physical abuse | Ever sexual abuse | |

| n = 2128 | n = 1509 | n = 1150 | n = 978 | n = 891 | n = 270 | n = 644 | n = 865 | n = 818 | n = 304 | |

| Total | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 14 to <20 | 69 (3.2) | 208 (13.8) | 18 (1.6) | 51 (5.2) | 48 (5.4) | 12 (4.3) | 80 (12.6) | 128 (14.7) | 122 (15.0) | 39 (13.2) |

| 20 to <25 | 139 (6.5) | 512 (33.9) | 58 (5.0) | 81 (8.3) | 74 (8.3) | 29 (10.5) | 207 (32.1) | 305 (35.3) | 288 (35.5) | 103 (34.8) |

| 25 to <30 | 455 (21.4) | 374 (24.8) | 238 (20.7) | 217 (22.2) | 197 (22.1) | 67 (24.3) | 165 (25.6) | 209 (24.2) | 194 (23.9) | 72 (24.3) |

| 30 to <35 | 883 (41.5) | 250 (16.6) | 516 (44.9) | 367 (37.5) | 330 (36.9) | 104 (37.7) | 120 (18.6) | 130 (15.0) | 119 (14.7) | 45 (15.2) |

| 35 to <40 | 494 (23.2) | 142 (9.4) | 270 (23.5) | 224 (22.9) | 209 (23.4) | 57 (20.7) | 59 (9.1) | 83 (9.6) | 80 (9.8) | 31 (10.5) |

| ≥40 | 88 (4.2) | 23 (1.5) | 50 (4.3) | 38 (3.9) | 35 (3.9) | 7 (2.5) | 13 (2.0) | 10 (1.2) | 9 (1.1) | 6 (2.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Black | 352 (16.5) | 524 (34.7) | 151 (13.1) | 201 (20.6) | 187 (20.9) | 60 (21.8) | 194 (30.1) | 330 (38.2) | 312 (38.4) | 99 (33.6) |

| Hispanic | 157 (7.4) | 731 (48.5) | 79 (6.9) | 78 (8.0) | 72 (8.1) | 25 (9.1) | 371 (57.6) | 360 (41.6) | 335 (41.2) | 111 (37.6) |

| White | 1413 (66.4) | 154 (10.2) | 815 (70.8) | 598 (61.2) | 543 (60.9) | 162 (58.9) | 42 (6.5) | 112 (12.9) | 108 (13.3) | 56 (19.0) |

| Other | 206 (9.7) | 100 (6.6) | 106 (9.2) | 100 (10.2) | 90 (10.1) | 28 (10.2) | 37 (5.8) | 63 (7.3) | 58 (7.1) | 29 (9.8) |

| Household Income | ||||||||||

| <$5000 | 22 (1.0) | 341 (22.6) | 6 (0.5) | 16 (1.6) | 14 (1.6) | 6 (2.2) | 137 (21.2) | 204 (23.6) | 193 (23.7) | 68 (23.0) |

| $5001–10 000 | 41 (1.9) | 203 (13.5) | 20 (1.7) | 21 (2.2) | 17 (1.9) | 10 (3.6) | 84 (13.0) | 119 (13.8) | 114 (14.0) | 42 (14.2) |

| $10 001–20 000 | 76 (3.6) | 302 (20.0) | 38 (3.3) | 38 (3.9) | 34 (3.8) | 12 (4.4) | 139 (21.6) | 163 (18.9) | 151 (18.6) | 56 (18.9) |

| $20 001–40 000 | 276 (13.0) | 346 (22.9) | 118 (10.3) | 158 (16.2) | 149 (16.7) | 48 (17.5) | 160 (24.8) | 186 (21.5) | 175 (21.5) | 59 (19.9) |

| $40 001–70 000 | 480 (22.6) | 201 (13.3) | 248 (21.6) | 232 (23.7) | 209 (23.4) | 71 (25.8) | 83 (12.9) | 118 (13.7) | 111 (13.7) | 42 (14.2) |

| >$70 000 | 1233 (57.9) | 116 (7.7) | 721 (62.6) | 512 (52.4) | 469 (52.6) | 128 (46.5) | 42 (6.5) | 74 (8.5) | 69 (8.5) | 29 (9.8) |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Less than high school | 63 (3.0) | 500 (33.1) | 16 (1.4) | 47 (4.8) | 46 (5.2) | 14 (5.1) | 235 (36.5) | 265 (30.6) | 249 (30.6) | 82 (27.7) |

| High school diploma | 200 (9.4) | 497 (32.9) | 91 (7.9) | 109 (11.2) | 98 (11.0) | 35 (12.7) | 198 (30.8) | 299 (34.6) | 279 (34.3) | 113 (38.2) |

| Some college | 490 (23.0) | 376 (24.9) | 255 (22.2) | 235 (24.0) | 211 (23.6) | 78 (28.2) | 143 (22.2) | 233 (27.0) | 219 (27.0) | 81 (27.4) |

| College degree | 751 (35.3) | 105 (7.0) | 429 (37.3) | 322 (32.9) | 294 (32.9) | 83 (30.1) | 51 (7.9) | 54 (6.2) | 52 (6.4) | 14 (4.7) |

| Graduate degree | 624 (29.3) | 31 (2.1) | 359 (31.2) | 265 (27.1) | 244 (27.3) | 66 (23.9) | 17 (2.6) | 14 (1.6) | 14 (1.7) | 6 (2.0) |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||

| Never smoker | 1851 (87.0) | 1086 (72.0) | 1035 (89.9) | 816 (83.5) | 746 (83.7) | 224 (81.7) | 545 (84.6) | 541 (62.5) | 503 (61.9) | 166 (56.1) |

| Current smoker | 64 (3.0) | 113 (7.5) | 22 (1.9) | 42 (4.3) | 37 (4.2) | 12 (4.4) | 27 (4.2) | 86 (10.0) | 84 (10.3) | 39 (13.1) |

| Past smoker | 213 (10.0) | 310 (20.5) | 94 (8.2) | 119 (12.2) | 108 (12.1) | 38 (13.9) | 72 (11.2) | 238 (27.5) | 226 (27.8) | 91 (30.8) |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Married | 1713 (80.5) | 387 (25.7) | 989 (85.8) | 724 (74.3) | 659 (74.0) | 191 (70.7) | 204 (31.7) | 183 (21.2) | 172 (21.0) | 61 (20.1) |

| Cohabiting | 231 (10.9) | 468 (31.0) | 94 (8.1) | 137 (14.0) | 126 (14.1) | 44 (16.3) | 204 (31.7) | 264 (30.5) | 252 (30.8) | 92 (30.2) |

| Single, divorced, other | 184 (8.6) | 654 (43.3) | 70 (6.1) | 114 (11.7) | 106 (11.9) | 35 (13.0) | 236 (36.6) | 418 (48.3) | 394 (48.2) | 151 (49.7) |

| Parity | ||||||||||

| 0 | 1017 (47.8) | 344 (22.8) | 562 (48.9) | 455 (46.5) | 415 (46.5) | 118 (42.9) | 141 (21.9) | 203 (23.5) | 190 (23.4) | 68 (23.0) |

| 1 | 761 (35.8) | 564 (37.4) | 405 (35.3) | 356 (36.4) | 323 (36.2) | 106 (38.6) | 258 (40.1) | 306 (35.4) | 290 (35.7) | 89 (30.1) |

| ≥2 | 350 (16.4) | 601 (39.8) | 182 (15.8) | 168 (17.1) | 154 (17.3) | 51 (18.5) | 245 (38.0) | 356 (41.1) | 332 (40.9) | 139 (46.9) |

| Place of birth | ||||||||||

| USA | 1677 (78.8) | 652 (43.2) | 892 (77.4) | 785 (80.5) | 715 (80.2) | 224 (83.0) | 201 (31.2) | 451 (52.1) | 433 (52.9) | 127 (41.8) |

| Outside USA | 451 (21.2) | 857 (56.8) | 261 (22.6) | 190 (19.5) | 176 (19.8) | 46 (17.0) | 443 (68.8) | 414 (47.9) | 385 (47.1) | 177 (58.2) |

| Childhood socio-economic position | ||||||||||

| Father’s education | ||||||||||

| Less than high school | 242 (11.4) | 110 (9.6) | 132 (13.5) | 123 (13.8) | 33 (12.0) | |||||

| High school/some college | 947 (44.5) | 504 (43.8) | 443 (45.3) | 400 (44.8) | 135 (49.1) | |||||

| College graduate | 939 (44.1) | 536 (46.6) | 403 (41.2) | 370 (41.4) | 107 (38.9) | |||||

| Parental home ownership | 858 (56.9) | 545 (84.6) | 541 (62.5) | 503 (61.9) | 166 (56.1) | |||||

aP < 0.0001 for chi-squared tests of age, race, income, education, smoking status, marital status, parity and mother’s place of birth by cohort.

bEver abuse and its subtypes are not mutually exclusive.

cUsing complete case assessment, Project Viva would have had n = 1346. However, 36.7% of women had at least one variable missing.

dUsing complete case assessment, Project ACCESS would have had n = 696. However, 53.9% of women had at least one variable missing.

Prevalence of abuse

Within both Projects Viva and ACCESS, women who reported a history of abuse were more likely than never-abused women to be unmarried, and born in the USA (Table 1). In Project Viva, women with a history of abuse were less likely to be at the top income and education levels. In Project ACCESS, abuse history was unassociated with household income. In Project ACCESS, abused women were somewhat more likely than unabused women to have completed high school.

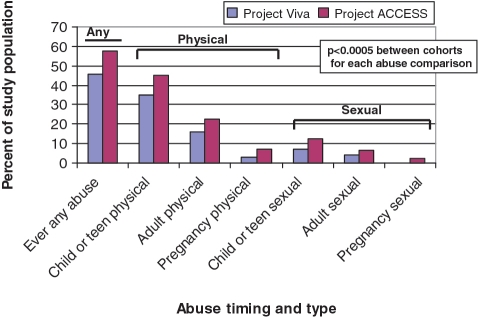

Figure 1 shows the distribution in each cohort of self-reported experiences of physical or sexual abuse in childhood and adolescence, adulthood (before this pregnancy) or during the index pregnancy. Reports of lifetime physical and sexual abuse were more common among women in Project ACCESS (54% reported physical and 20% sexual abuse) than in Project Viva (42% physical and 13% sexual abuse). Despite this difference, the pattern of abuse type and timing was similar in the two cohorts: abuse prevalence was highest in childhood and adolescence, and physical abuse was more commonly reported than sexual abuse. Three-quarters (75%) of the women who reported sexual abuse also reported physical abuse, but only one-quarter (26%) of the women who reported physical abuse also reported sexual abuse; this pattern was evident in both cohorts. Abuse during pregnancy was more commonly reported by Project ACCESS participants than Project Viva participants.

Figure 1.

Distribution of abuse timing and type in Project Viva and Project ACCESS

Prevalence of pre-natal depression

Project Viva participants were half as likely as Project ACCESS participants to report symptoms consistent with pre-natal depression: at mid-pregnancy, 11.3% of Project Viva participants had EPDS scores ≥13, compared with 22.2% of Project ACCESS participants.

Association of abuse with depression

In merged analysis (Table 2), women reporting any lifetime abuse had an unadjusted OR for depression of 1.79 (95% CI 1.43–2.25), which was reduced by adjustment for age and race/ethnicity to 1.63 (95% CI 1.29–2.07). Further adjustment for the potential intermediate adult risk factors of education, marital status, parity, income and smoking reduced this estimate to 1.48 (95% CI 1.17–1.88). A history of physical abuse was associated with 48% higher odds and history of sexual abuse with 68% higher odds of depression during pregnancy after adjusting for age and race/ethnicity. Further adjustment for education, marital status, parity, income and smoking modestly attenuated these estimates [OR = 1.38 (95% CI 1.07–1.78) for physical and 1.54 (95% CI 1.13–2.08) for sexual abuse].

Table 2.

ORs (95% CIs) for lifetime abuse history and odds of pre-natal depression, Project Viva and Project ACCESS

| Number in merged cohorts | Number (%) with depression symptoms | Crude model, merged cohorts | Age- and race-adjusted model, merged cohorts | Age- and race-adjusted model, Project Viva | Age- and race-adjusted model, Project ACCESS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never abused | 1794 (49.3) | 214 (11.9) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Ever abuseda | 1843 (50.7) | 361 (19.6) | 1.79 (1.43–2.25) | 1.63 (1.29–2.07) | 1.43 (1.00–2.04) | 1.79 (1.33–2.41) |

| Type of abuseb | ||||||

| Ever physical | 1705 (46.9) | 340 (19.9) | 1.62 (1.27–2.06) | 1.48 (1.15–1.90) | 1.42 (1.01–1.99) | 1.49 (1.08–2.08) |

| Ever sexual | 570 (15.7) | 141 (24.7) | 1.71 (1.27–2.31) | 1.68 (1.24–2.28) | 1.25 (0.72–2.17) | 1.95 (1.32–2.89) |

| Timing of abusec | ||||||

| Child/teen | 1558 (42.8) | 303 (19.4) | 1.35 (1.08–1.70) | 1.26 (1.00–1.59) | 1.36 (0.93–2.00) | 1.27 (0.94–1.73) |

| Pre-pregnancy adult | 768 (21.1) | 186 (24.2) | 1.72 (1.33–2.22) | 1.70 (1.31–2.21) | 1.27 (0.83–1.96) | 1.89 (1.35–2.64) |

| Pregnancy | 188 (5.2) | 60 (31.9) | 2.05 (1.33–3.17) | 1.77 (1.14–2.74) | 1.63 (0.66–4.04) | 1.73 (1.00–3.02) |

aModels contrast ever abuse vs never abuse; reference is never abuse.

bModels include terms for ever physical and ever sexual abuse; reference is never abuse.

cModels include terms for child/teen abuse, pre-pregnancy adult abuse, and pregnancy abuse; reference is never abuse.

Recency of abuse was associated with odds of pre-natal depression. In models considering each time period simultaneously (Table 2), the odds of depression associated with abuse were higher with more recent abuse, rising from a 26% increased odds with child or teen abuse, to 70% with adult abuse before the pregnancy to 77% increased odds with abuse during pregnancy. The magnitude of the association between child and adolescent abuse with depression was similar for women with adult abuse experiences [OR = 1.28 (95% CI 0.80–2.05) for child/teen abuse] and without adult abuse experiences [OR = 1.25 (95% CI 0.93–1.68)].

Interactions of abuse with socio-demographic factors

A few associations of abuse with depression appeared to be modestly stronger in Project Viva than in Project ACCESS, notably ‘ever sexual abuse’ and ‘pre-pregnancy adult abuse’ (Table 2). However, no tests of interaction between cohort membership and abuse variables indicated statistically significant differences between cohorts in these associations. We also tested interactions of any abuse, physical abuse and sexual abuse with maternal education, race/ethnicity, immigrant status and parental education (Viva) or home ownership (ACCESS). We observed neither clinically nor statistically significant interactions of abuse with these socio-demographic factors in predicting pre-natal depression (all interaction P > 0.10), with the possible exception of an interaction of abuse with education, where the data suggested that abuse was a stronger risk factor for depression among women with less education (P = 0.10 for ever abuse* education).

Comparison of ‘complete case’ analysis with imputed analysis

There was a large degree of missing data from both cohorts, which led us to use multiple imputation. In both cohorts, the missing data stemmed from failure to respond to one or more of the several questionnaires administered during pregnancy; fewer than 3% of the women in either cohort left the abuse or depression scales blank on a returned questionnaire. We compared the results of the imputed analysis with a ‘complete case’ analysis among women who were missing no covariates for this analysis. This reduced sample size by 37% in Project Viva and 54% in Project ACCESS. Women who provided complete data were of higher socio-economic status, more likely to be White, less likely to have experienced abuse (43%) and less likely to have pre-natal depression (12%). Despite these differences, the associations of abuse with depression were similar, with the following exceptions: in the ‘complete case’ analysis, the associations of sexual abuse with depression were somewhat stronger [OR = 2.20 (95% CI 1.52–3.19) for ‘ever sexual abuse’], driven by a higher estimate associated with sexual abuse in Project ACCESS [3.59 (95% CI 2.10–6.15)]. Associations of pre-pregnancy adult abuse and pregnancy abuse were somewhat stronger in the ‘complete case’ analysis [2.01 (95% CI 1.45–2.80) and 2.91 (95% CI 1.60–5.28), respectively] than in the imputed analysis. The most notable difference was the strong and consistent interaction of abuse history with maternal education in the ‘complete case’ analysis (P = 0.02, 0.02 and 0.004 in merged analysis for interactions of years of education with any abuse, physical abuse and sexual abuse, respectively).

Discussion

Women with lifetime physical or sexual abuse had a 63% increased odds of experiencing depression during pregnancy. Although the odds of depression were greater if abuse was recent, we nevertheless observed a 26% higher risk associated with abuse in child/teen years after adjustment for later abuse. The odds of pre-natal depression were 70–77% higher for women who experienced physical or sexual abuse in adulthood, either before or during pregnancy; this group represented 16% of the more privileged Project Viva and 23% of the less advantaged Project ACCESS. Although the data suggest that more recent abuse is a greater risk for depression during pregnancy than remote child abuse, it is possible that this apparent ‘recency effect’ is the product of poor recall of distant events.

Our findings extend those of Holzman and colleagues,10 who examined pre-natal depression symptoms in five Michigan communities participating in the POUCH study. Our analysis adds to the POUCH findings in several ways: we examined the prevalence of probable major and minor depression, rather than variation in depression scores across a range of normal and abnormal symptomatology; we assessed abuse exposure with the more extensive Personal Safety Questionnaire, in contrast to three questions regarding abuse used by the POUCH study; and we examined physical and sexual abuse histories separately, demonstrating similar increases in risk of depression with both types of abuse. Similar to our study, POUCH found that pregnant women who had recently experienced or witnessed abuse had higher scores on the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D). The POUCH study reported that abuse history had a stronger association with pre-natal depression risk among disadvantaged women; our data suggested a similar interaction of abuse and maternal education (P = 0.10 for interaction in the imputed analysis; P = 0.02 for interaction in the ‘complete case’ analysis). The two studies raise the possibility that a history of abuse, especially if sexual, is a particularly potent risk factor for depression among women with lower socio-economic position. There may be other interactions between abuse and social factors that our analysis was too small to detect.

The patterns of abuse reported by women in these two Boston metropolitan area cohorts are consistent with reports from a nationwide survey indicating that 55% of adult women report physical abuse or rape in their lifetime, with most abuse occurring before the age of 18 years.28 Forty-six percent of the women in the more socio-economically advantaged Project Viva and 56% of mothers in the less advantaged Project ACCESS reported physical or sexual abuse in their lifetime. Most studies have estimated that 4–8% of pregnant women are abused,29 although higher rates are generally reported from urban public clinics.30,31 Our findings are consistent with national socio-economic patterns: 3% of Viva and 9% of ACCESS participants reported abuse during the current pregnancy.

One notable strength of this study is the unusual opportunity to examine the prevalence of abuse and the associations of abuse and depression using identical study instruments within two socio-demographically distinct populations in one city at the same time, allowing us to directly compare the associations of abuse with depression across a broad range of demographics. Our study has several limitations. As in most large-scale studies, we were not able to diagnose clinical depression by psychiatric interview, but instead relied upon the validated EPDS. As in other studies, we relied upon self-reported experiences of abuse, whose validity cannot be tested against an external ‘gold standard,’ as most child abuse is never reported to the authorities.32 Inaccurate recall of past events might be especially problematic for remote child abuse, and resulting misclassification may have weakened estimates of associations with child abuse in this and other studies. As in other studies,8–15,33 the simultaneous assessment of depression symptoms and retrospective report of abuse history could have resulted in a greater likelihood that depressed women recalled abusive events.34 However, our use of an abuse assessment tool that queries specific acts without labelling them ‘abusive’ may have helped to minimize this potential bias. Lastly, although we adjusted for parental education, parental home ownership and adult income, the associations we observed between abuse and pre-natal depression may be explained by more subtle differences in socio-economic position that we did not measure.

In summary, we found that a history of physical or sexual abuse was a risk factor for pre-natal depression in both community health centre and managed care settings. Roughly 45–60% of mothers had experienced physical or sexual abuse at some point in their lives, whether they were more or less privileged. Although recent abuse was associated with especially high risks of pre-natal depression, a history of abuse confined to childhood and adolescence appeared to have a modest increase in risk of pre-natal depression that might have been biased towards the null by inaccurate recall. Despite the higher prevalence of abuse and depression in the more disadvantaged cohort, the associations of abuse with risk of depression were similar in the two cohorts.

A full accounting of the sequelae of physical and sexual abuse should include the risks of depression throughout the life-course, including during pregnancy. A growing body of studies clearly indicates that abuse is strongly associated with risk of depression, providing more impetus for programmes to prevent abuse of girls and women. Interventions that reduce the psychological impact of abuse may reduce the risks of poor mental health during the childbearing years, resulting in less suffering and improved family function and health. Since many women enter pregnancy with a history of untreated abuse, health-care providers should query the physical and sexual abuse histories of their pregnant clients, and be alert to the high risks of pre-natal depression among women with a history of abuse.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (grants R01MH068596, R01ED10932, R01HL080674 and R01HD034568).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the input of Dr Sally Zierler in designing the Personal Safety Questionnaire and for the advice of Dr Hadine Joffe regarding anti-depressant use during pregnancy.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol April. 2004;103:698–709. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dossett EC. Perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35:419–34, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:49–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolaidis C, Curry M, McFarland B, Gerrity M. Violence, mental health, and physical symptoms in an academic internal medicine practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:819–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30382.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hegarty K, Gunn J, Chondros P, Small R. Association between depression and abuse by partners of women attending general practice: descriptive, cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2004;328:621–24. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7440.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kendall-Tackett KA. Violence against women and the perinatal period: the impact of lifetime violence and abuse on pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8:344–53. doi: 10.1177/1524838007304406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benedict MI, Paine LL, Brandt D, Stallings R. The association of childhood sexual abuse with depressive symptoms during pregnancy, and selected pregnancy outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:659–70. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens-Simon C, McAnarney E. Childhood victimization: relationship to adolescent pregnancy outcome. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1994;18:569–75. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holzman C, Eyster J, Tiedje L, Roman L, Seagull E, Rahbar M. A life course perspective on depressive symptoms in mid-pregnancy. Maternal & Child Health J. 2006;10:127–38. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romano E, Zoccolillo M, Paquette D. Histories of child maltreatment and psychiatric disorder in pregnant adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adol Psych. 2006;45:329–36. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000194563.40418.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mezey G, Bacchus L, Bewley S, White S. Domestic violence, lifetime trauma and psychological health of childbearing women. BJOG: An Int J Obs Gyn. 2005;112:197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin SL, Li Y, Casanueva C, Harris-Britt A, Kupper LL, Cloutier S. Intimate partner violence and women's depression before and during pregnancy. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:221–39. doi: 10.1177/1077801205285106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung EK, Mathew L, Elo IT, Coyne JC, Culhane JF. Depressive symptoms in disadvantaged women receiving prenatal care: the influence of adverse and positive childhood experiences. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2008;8:109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Records K, Rice MJ. A comparative study of postpartum depression in abused and nonabused women. Arch Psych Nursing. 2005;19:281–90. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin SL, Mackie L, Kupper LL, Buescher PA, Moracco KE. Physical abuse of women before, during, and after pregnancy. JAMA. 2001;285:1581–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence Vict. 2004;19:507–20. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray DM, Cox JL. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh depression scale. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1990;11:119–25. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Righetti-Veltema M, Conne-Perreard E, Bousquet A, Manzano J. Risk factors and predictive signs of postpartum depression. J Affective Disord. 1998;49:167–80. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warner R, Appleby L, Whitton A. Demographic and obstetric risk factors for postnatal pyschiatric morbidity. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:605–11. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rich-Edwards JW, Mohllajee AP, Kleinman K, et al. Elevated midpregnancy corticotropin-releasing hormone is associated with prenatal, but not postpartum, maternal depression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1946–51. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman K, Abrams A, et al. Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:221–27. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthey S, Henshaw C, Elliott S, Barnett B. Variability in use of cut-off scores and formats on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale – implications for clinical and research practice. Arch Women's Mental Health. 2006;9:309–15. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M. Amelia II: A Program for Missing Data. 2009. http://gking.harvard.edu/amelia (7 December 2010, date last accessed)

- 26.King G, Honaker J, Joseph A, Scheve K. Analyzing incomplete political science data: An alternative algorithm for multiple imputation. Am Political Sci Rev. 2001;95:20. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horton NJ, Kleinman KP. Much ado about nothing: A comparison of missing data methods and software to fit incomplete data regression models. Am Stat. 2007;61:79–90. doi: 10.1198/000313007X172556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, Nature and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Rockville, MD: National Criminal Justice Reference Service, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gazmararian JA, Lazorick S, Spitz AM, Ballard TJ, Saltzman LE, Marks JS. Prevalence of violence against pregnant women. JAMA. 1996;275:1915–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker B, McFarlane J, Soeken K. Abuse during pregnancy: effects on maternal complication and birth weight in adult and teenage women. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:323–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gielen AC, O'Campo PJ, Faden RR, Kass NE, Xue X. Interpersonal conflict and physical violence during the childbearing year. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:781–87. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:260–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leigh B, Milgrom J. Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thombs BD, Bernstein DP, Ziegelstein RC, et al. An evaluation of screening questions for childhood abuse in 2 community samples: implications for clinical practice. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2020–26. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.18.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]