Abstract

Objective

Following spinal cord injury (SCI), certified therapeutic recreation specialists (CTRSs) work with patients during rehabilitation to re-create leisure lifestyles. Although there is much literature available to describe the benefits of recreation, little has been written about the process of inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation therapeutic recreation (TR) programs or the effectiveness of such programs. To delineate how TR time is used during inpatient rehabilitation for SCI.

Methods

Six rehabilitation centers enrolled 600 patients with traumatic SCI for an observational study. CTRSs documented time spent on each of a set of specific TR activities during each patient encounter. Patterns of time use are described, for all patients and by neurologic category. Ordinary least-squares stepwise regression models are used to identify patient and injury characteristics predictive of total treatment time (overall and average per week) and time spent in TR activities.

Results

Ninety-four percent of patients enrolled in the SCIRehab study participated in TR. Patients received a mean total of 17.5 hours of TR; significant differences were seen in the amount of time spent in each activity among and within neurologic groups. The majority (76%) of patients participated in at least one structured therapeutic outing. Patient and injury characteristics explained little of the variation in time spent within activities.

Conclusion

The large amount of variability seen in TR treatment time within and among injury group categories, which is not explained well by patient and injury characteristics, sets the stage for future analyses to associate treatments with outcomes.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries, Rehabilitation, Health services research, Therapeutic recreation, Paraplegia, Tetraplegia

Introduction

Most individuals who incur a spinal cord injury (SCI) experience a shift in how they spend their time, with a decrease in work and other productive activities, and an increase in leisure activities and (to a smaller degree) self-care.1–3 Often, there also are shifts within leisure activities, with a decrease in sports participation and increases in indoors and sedentary activities, especially watching TV and listening to radio and music.1,4,5 It is reasonable to expect that for people with SCI, leisure activities and recreation are more important to overall quality of life (QOL) than they are for the able-bodied. However, there is evidence that this domain of life is less satisfactory for people with SCI than are other domains6,7 and that they are dissatisfied with the work/leisure balance2 and grieve lost leisure opportunities.8

There is much evidence that for people with SCI, frequent participation in leisure activities, especially sports and other active pursuits, has a positive association with life satisfaction, self esteem, and mood state.4,9–11 More physically, active pursuits have, in addition, been shown to correlate with health and the need for health services.12,13 As most of the studies are cross-sectional, it cannot be assumed that active leisure is the cause here; it may be that high life satisfaction and QOL encourage people to engage in active and diversified leisure, or that both subjective well-being and an active leisure lifestyle are joint effects of yet another factor. A few interventional studies that have been done14–16 however, justify exposing individuals with SCI to adapted means of pursuing preinjury recreational activities, exploring new interests, and overcoming barriers to an active leisure life. The certified therapeutic recreation specialist (CTRS) on the rehabilitation team provides this expertise and is trained to work with patients to re-create their leisure lifestyle.

Therapeutic recreation's (TR) primary responsibility in working with patients with SCI is to expose them to appealing and realistic leisure options following injury. Assessment of preinjury lifestyle provides the foundation for moving forward and implementing a treatment plan that facilitates the patient's return to preinjury activities and/or the development of new interests to promote an independent, active lifestyle.

TR can bring about lifestyle and activity modifications that allow the patient to pursue preferred leisure pursuits. Noreau and Fougeyrollas17 found significant disruptions in the areas of recreational and physical activities after injury. They recommend that SCI rehabilitation centers incorporate programs that include structured exercise conditioning18 and suggest that physiological improvements can be gained by engagement in fitness programs. In rehabilitation settings, CTRSs have the chance to expose patients to opportunities to participate in recreational activities that promote fitness.

To date there is almost no literature describing what types and quantities of services TRs deliver in the inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation setting, and what results, short term and long term, they help to achieve. Measurement of interventions and association with outcomes may speak to Hoss and McCormick's conclusion that ‘the field continues to lack abilities to demonstrate the provision of outcomes (p. 40).’19

The SCIRehab Project is a multi-center, 5-year investigation that is recording and analyzing the details of SCI rehabilitation processes for approximately 1400 patients enrolled over 2.5 years. This paper aims to use data from the first year of data collection to describe how TR time is used during rehabilitation and how time use differs for patients with different levels and completeness of injury. We also explore whether other patient demographic and injury characteristics are associated with the time used for various TR interventions. Understanding how CTRSs spend time overall and on specific activities will form the foundation for future work that will associate details of the TR portion of the rehabilitation process with patient outcomes, in the area of leisure and otherwise, at 12-month post-injury.

Methods

The introductory paper20 describes the SCIRehab project's study design, including use of the practice-based evidence research methodology,21–26 study details such as inclusion criteria and data sources, and the analysis plan. We provide only a summary here. Briefly, the SCIRehab team included representatives of all rehabilitation clinical disciplines (including TR) from six inpatient rehabilitation facilities: Craig Hospital, Englewood, CO; Shepherd Center, Atlanta, GA; Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Carolinas Rehabilitation, Charlotte, NC; The Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY; and National Rehabilitation Hospital, Washington, DC. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained at each center and patients who were 12 years of age or older, gave (or their parent/guardian gave) informed consent, and were admitted to the facility's SCI unit for initial rehabilitation following traumatic SCI, were enrolled.

Patient/injury and clinician data

Trained data abstractors collected patient and injury data from patient medical records. The International Standards of Neurological Classification of SCI27 were used to describe the motor level and the completeness of injury. Patients with ASIA impairment scale (AIS) grade D were grouped together regardless of injury level. Patients with AIS classifications of A, B, and C were combined and separated by motor level to create the remaining three injury groups: C1–C4, C5–C8, and paraplegia. These injury categories were selected because they were each large enough for analysis and created groupings with relatively homogenous functional ability within groups and clear differences between groups. The Comprehensive Severity Index (CSI®) was utilized to quantify the extent of deviation from normal physiological status each of a patient's complications and comorbidities constituted, at the time of rehabilitation admission and over time during the rehabilitation stay.28–32 The higher the patients’ CSI score, the more deviant from normal (‘the sicker’) they were. The Functional Independence Measure (FIM®) was used to describe a patient's level of independence in motor and cognitive skills at rehabilitation admission and discharge.33,34 CTRSs who documented treatment for the SCIRehab project completed a clinician profile that included their years of SCI rehabilitation experience at the start of the project.

Therapeutic recreation treatment data

CTRSs at each SCIRehab site entered details about each TR session with each study patient into a handheld personal digital assistant (PDA) (Hewlett Packard PDA hx2490b, Palo Alto, CA) containing a modular custom application of the SCIRehab point of care (POC) documentation system, which incorporates the TR activities taxonomy (PointSync Pro version 2.0, MobileDataforce, Boise, ID, USA). This taxonomy has been described in detail previously35 and includes five activity categories commonly employed in TR treatment in an SCI rehabilitation setting: leisure education and counseling, leisure skill work in center, leisure skill outings, community outings, and social activity. It also includes initial patient assessment, classes led by CTRSs that patients attend, and interdisciplinary conferences in which CTRSs participate (Table 1). In this report, camping/hunting trip outings are reported separately from other leisure skill-focused outings because: (1) they are the only type that involves overnight stays and thus could consume up to several days in comparison to traditional outings that typically last several hours, and (2) only one center's operating procedures allow for patients to be out of the center overnight on hospital-sponsored outings.

Table 1.

TR: activity categories and details of activities/topics classified within each*

| Leisure education and counseling | Leisure skill work in center | Outing – leisure skills | Outings – community | Social Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge planning/ resource/equipment funding Personal care Energy conversation Health and wellness Money management Accessibility Advocacy/assertiveness Potential leisure options/adaptive equipment Problem-solving skills Schooling Self-image Stress management Time management Transportation Travel Values and benefits Wheelchair mobility |

Sports Creative expressions Outdoor Horticulture Aquatics Other |

Sports Creative expressions Outdoor: hunting and camping† Outdoor (other than hunting and camping) Horticulture Aquatics Other |

Airport Amusement park Community events Entertainment venues Gambling Hot air ballooning Museum/zoo/botanical garden Park Religious event Shopping Spectator sports Theater/movie Tours Train/bus Salon School/campus Other |

Animal visits Games Movies Performance Social gathering Peer visit Other |

*Initial assessment, interdisciplinary conferences, and classes (led by CTRSs) also were activity categories, but are not included as no additional subcategory detail were collected on these TR activities.

†In reporting time spent on activities in this report, hunting and camping are a different category of the aggregate of other ‘outing-leisure skills’ subclasses. See text.

The only other discipline contributing data to SCIRehab to document details (including time spent) on outings away from the hospital was occupational therapy (OT), so to obtain a picture of all ‘structured out-of-hospital therapeutic outings’, we determined the number of patients who participated in at last one OT community reintegration outing and/or one TR outing.

In-hospital social activities, e.g, concerts, performances, movies, parties, and gatherings organized for patients are a valuable component of TR intervention, but, because they typically take place during open-ended, non-structured time, with patients coming and going as they desire, it was challenging to quantify time spent by individual patients in these activities. Thus, the TR documentation allowed clinicians to record social events in which patients participated that were under the direction of TR, even if coordinated by volunteers or other staff, but did not require them to quantify time spent. This record does not include spontaneous social activities, such as gatherings of patients, families, etc., which may have taken place in addition to organized TR activities.

Each therapist was trained and tested quarterly on the use of the documentation system. Entries made each day were compared with TR patient schedules and other records to ensure that all sessions were included in the TR documentation. Entered into the PDA were the date/time of each TR session, the number of minutes spent on intervention activities performed (except for social activities), activity-specific details, levels of patient and family participation, and factors that limited session activities.35 The present paper reports only on time spent in treatment categories. The numbers of minutes recorded for all activities that made up a treatment session were combined to equal the approximate duration of the entire TR session. Minutes spent in the same activity category were added across the entire stay to quantify therapy time allocated to specific interventions.

Data analysis

The data reported here are for the patients enrolled in the SCIRehab project's first year of enrollment. Time spent in TR treatment on successive days was combined to derive the total number of hours of TR received during the rehabilitation stay. Because total TR time and hours in specific TR activities are strongly correlated with the opportunity to receive services as fundamentally determined by length of stay (LOS), we calculated the average minutes per week spent in TR treatment and used this as the primary measure of TR treatment intensity. Contingency tables/chi-square tests and ANOVA were used to test differences across injury groups for categorical and for continuous variables, respectively. Differences with a P value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

For TR activities in which at least 70% of patients participated, patient and injury characteristics associated with weekly time spent were examined using ordinary least-squares stepwise regression models. The strength of the model is determined by the R2 value, which indicates that amount of variation explained by the significant variables. Parameter estimates indicate the direction and strength of the association between each statistically significant independent variable (predictor) with the dependent variable (outcome). Type II semi-partial correlation coefficients allowed for estimation of the unique contribution of each predictor variable after controlling for all other variables in the model.36,37 At the onset of the SCIRehab project, the clinical team identified variables thought to be important to the rehabilitation process and thus, to have potential to influence patient outcomes. These variables (predictors) were entered into regression models: gender, marital status, racial/ethnic group, traumatic SCI etiology, body mass index (BMI), English proficiency, third party payer, preinjury occupational status, severity of illness score (CSI), age, FIM score, experience level of the clinician, and neurologic injury group. Only if the predictors jointly explained 20% or more of the variance in the number of TR minutes per week are model details shown.

Results

Details of patient demographic and injury characteristics are presented for the study sample as a whole and for each of the four injury groups separately in the first article in this SCIRehab series (Table 1).20 The average age of subjects was 37 years, with a standard deviation (SD) of 17. The sample was 81% male, 65% white and 22% black, 38% married, mostly not obese (82% had a BMI of <30), and 65% were employed at the time of injury. Vehicular crashes were the most common cause of injury (49%), falls were the next most common (23%), followed by sports and violence (11% each). The mean rehabilitation LOS was 55 days (range 2–259, SD 37, median 43). The mean total FIM score at admission was 53 (SD 15), with a mean motor score of 24 (SD 12) and a cognitive score of 29 (SD 6). A mean of 32 days (SD 28) had elapsed from the time of injury to the time of rehabilitation admission.

Of these 600 patients, 94% received one or more TR treatment sessions during their rehabilitation stay. SCIRehab CTRSs documented treatment provided within the five TR activities (including three types of outings), during 8207 sessions (4120 individual TR sessions and 4087 group sessions). The patients received a mean total of 17.5 hours (range 0–99.6, SD 16.5, median 13.9) of TR. (As indicated, this omits hours in TR-organized social activities.) Total hours over the full rehabilitation stay within these activities and the average number of minutes per week for the full sample and for the four injury groups separately are shown in Table 2. The mean number of minutes per week for the full sample was 155 (range 0–1124, SD 147, median 129). Significant differences were seen in the amount of time spent in each activity among the four injury groups. For social activities, the percentage of patients who participated is reported along with the mean number of social activity sessions for each injury group. Significantly fewer patients within the AIS D injury group (29%) had documented social activities compared with the entire sample (56%).

Table 2.

TR: percent of patients receiving each type of activity, mean total hours, and mean minutes/week (standard deviation)*

| Full SCIRehab sample n = 600 | C1-4 AIS A, B, C n = 132 | C5-8 AIS A, B, C n = 151 | Para AIS A, B, C n = 223 | AIS D n = 94 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any TR intervention (%) | 94 | 95 | 97 | 96 | 83 |

| Total hours | 17.5 (16.5) | 18.9 (14.7) | 23.7 (20.8) | 16.5 (14.6) | 8.0 (9.2) |

| Minutes/week | 154.9 (146.9) | 130.4 (101.1) | 181.5 (165.8) | 175.2 (164.9) | 98.6 (95.2) |

| Initial assessment (%) | 52 | 52 | 52 | 54 | 47 |

| Total hours | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.4) |

| Minutes/week† | 3.2 (4.8) | 2.2 (2.9) | 2.3 (3.2) | 3.5 (4.5) | 5.1 (8.2) |

| Leisure education and counseling (%) | 80 | 85 | 89 | 81 | 59 |

| Total hours | 2.4 (2.0) | 2.6 (1.9) | 2.7 (1.9) | 2.5 (2.0) | 1.3 (1.5) |

| Minutes/week† | 23.2 (22.1) | 20.5 (18.9) | 22.5 (19.3) | 28.1 (24.8) | 16.5 (21.4) |

| Leisure skills in center (%) | 80 | 82 | 89 | 83 | 57 |

| Total hours | 4.6 (4.6) | 4.6 (4.6) | 6.0 (5.1) | 4.6 (4.4) | 2.5 (3.8) |

| Minutes/week† | 42.1 (41.7) | 34.9 (35.9) | 46.6 (39.4) | 48.8 (46.8) | 28.9 (35.4) |

| Outing – camping and hunting (%) | 3 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| Total hours | 1.2 (7.4) | 0.1 (1.0) | 2.8 (11.4) | 1.1 (7.5) | 0.0 (0.5) |

| Minutes/week† | 10.9 (75.9) | 0.4 (2.9) | 21.6 (91.9) | 14.5 (98.1) | 0.3 (2.5) |

| Outing – leisure skills (%) | 22 | 19 | 26 | 26 | 10 |

| Total hours | 1.3 (3.6) | 1.3 (3.7) | 2.0 (4.9) | 1.2 (2.8) | 0.6 (2.2) |

| Minutes/week† | 9.3 (21.9) | 5.8 (15.7) | 11.4 (23.7) | 11.5 (24.2) | 5.6 (19.8) |

| Outing – community (%) | 66 | 74 | 70 | 69 | 40 |

| Total hours | 5.9 (7.4) | 7.9 (9.0) | 7.7 (8.1) | 5.1 (6.2) | 2.1 (3.5) |

| Minutes/week† | 50.8 (60.4) | 53.7 (58.8) | 61.3 (69.8) | 52.3 (58.0) | 26.5 (44.4) |

| Interdisciplinary conferencing (%) | 86 | 87 | 89 | 86 | 76 |

| Total hours | 1.3 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.6) | 1.1 (1.3) | 1.0 (1.4) |

| Minutes/week† | 11.6 (12.3) | 9.2 (7.6) | 12.1 (11.4) | 11.7 (11.4) | 14.1 (19.0) |

| Classes (%) | 37 | 45 | 42 | 39 | 15 |

| Total hours | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.2 (0.5) |

| Minutes/week† | 3.9 (6.6) | 3.8 (5.0) | 3.9 (5.8) | 4.9 (8.2) | 1.6 (4.5) |

| Social activity‡ | |||||

| Percentage participating (%) | 56 | 65 | 68 | 53 | 29 |

| Mean number of sessions (SD) | 3.5 (3.8) | 3.9 (3.9) | 3.9 (4.3) | 3.1 (3.3) | 2.9 (3.4) |

*Hours and minutes per week are averages over all 600 patients, not just based on those who did receive one or more sessions of a particular activity.

†Statistically significant differences in mean minutes per week among groups.

‡Time is not recorded for social activity; instead, percentage of patients and mean number of sessions is reported.

The majority (76%) of patients participated in at least one structured therapeutic outing (led by either TR or OT). Participation was similar among injury groups (about 80%) except for injury group AIS D, which had a participation rate of 50%.

Of all patients, 22% participated in outings that involved learning or improving a leisure skill; however, many more patients (80%) participated in leisure skill work within the rehabilitation center. Most leisure skill-oriented outings (77%) focused on sports or outdoor activities with bowling, fishing, boating, target shooting, scuba diving, and hand-cycling accounting for over 70% of the skills practiced. Leisure skill work in the rehabilitation center commonly focused on crafts, fitness, gardening, and board/ card/ video games.

Fig. 1 depicts the substantial variation in mean minutes per week seen within all TR activities for the sample as a whole. For community outings, the interquartile range (IQR) was 0–84 (median 30), for leisure skills in center the IQR was 7–65 (median 31), and for leisure education and counseling the IQR was 6–36 (median 17) minutes per week. Fewer than half of the patients participated in leisure skill outings (the median number of minute per week was 0 for the entire sample and for each injury group). The IQR for patients in the Para: ABC injury group was 0–51 and the median was 0, indicating that even in the least-impaired group at least half of the patients did not take part in one or more leisure skill outings.

Figure 1.

Time spent (minutes per week) in TR activities.

Notes: *3% of sample, all above 95th percentile; †22% of sample, all above 75th percentile; ‡37% of sample, median=0

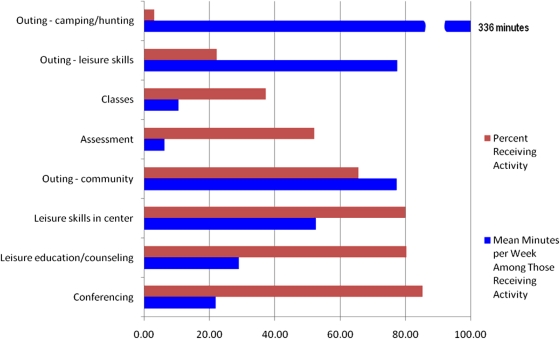

Fig. 2 displays the percentage of patients receiving each TR activity and the mean number of minutes per week spent on each activity for these patients only. For example, 80% of patients received leisure education and counseling and a mean of 30 minutes per week was spent on this activity by the 480 individuals involved. Similarly, 65% of patients went on TR-organized community outings that lasted 75 minutes per week, on average. Only 2% of patients participated in camping/hunting outings, but these patients spent a mean of 336 minutes per week on these outings.

Figure 2.

TR activities (% receiving and time spent) for all patients (mean minutes per week).

Patient and injury characteristics that were associated with the amount of time (minutes per week) spent on the TR activities of leisure skills in center and leisure education/counseling are reported in Table 3. Other TR activities did not have at least 70% of patients participate in the activity or the regression model did not have sufficient explanatory power (R2 < 0.20); and thus are not reported. The regression model for the TR activity of leisure skills in center explains 21% of the variation in time spent (R2 = 0.21). The parameter estimate for the independent variable of severity of illness score (CSI) is −0.22, which indicates that for each additional severity point, 0.22 fewer minutes were spent compared to a patient with a CSI score of zero (no comorbidities) and the semi-partial R2 (0.02) indicates that the unique contribution of this variable is 2% (after controlling for all other variables in the model). Other patient/injury characteristics associated with less time (negative parameter estimate) included older age, being male, injury group AIS D, employment status-other (as compared to working, student, retired, unemployed), race-black, traumatic etiologies of violence and medical/surgical complications, and treatment by clinicians with higher levels of experience. For the leisure education and counseling activity, patient demographic and injury characteristics combined explained 22% of the variation in time spent (R2 = 0.22). Factors associated with more time spent (positive parameter estimates) in leisure education and counseling included being married, race-white, being employed or a student, and injury group Para: ABC. Higher severity of illness score, injury group AIS D, traumatic etiology-medical/surgical complications, sufficient proficiency in English communication, having a BMI > 40, and treatment by clinicians with higher levels of experience were associated with less time spent (negative parameter estimates) in leisure education and counseling.

Table 3.

Patient and injury characteristics associated with time (minutes per week) spent in TR activities*,†

| Leisure skills in center |

Leisure education and counseling |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total R2 | 0.21 |

0.22 |

||

| Independent variable | Parameter estimate | Type II semi-partial R2 | Parameter estimate | Type II semi-partial R2 |

| Age at injury | −0.43 | 0.02 | ||

| Injury group: AIS D | −17.88 | 0.02 | −5.82 | 0.01 |

| Injury group: Para ABC | 5.96 | 0.01 | ||

| BMI 30–40 | 9.68 | 0.01 | ||

| BMI >40 | −14.16 | 0.01 | ||

| Clinician experience | −1.16 | 0.04 | −0.68 | 0.05 |

| Employment status at time of injury – student | 9.18 | 0.01 | ||

| Employment status at time of injury – working | 8.61 | 0.02 | ||

| Employment status at time of injury – other | −24.57 | 0.02 | ||

| English sufficient for understanding | −16.22 | 0.01 | ||

| Male | −9.50 | 0.01 | ||

| Married | 5.16 | 0.01 | ||

| Severity of illness score (CSI) | −0.22 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.01 |

| Race-black | −9.61 | 0.01 | ||

| Race-white | 3.66 | 0.01 | ||

| Traumatic etiology – violence | −13.07 | 0.01 | ||

| Traumatic etiology – medical/surgical complications | −17.17 | 0.01 | −10.00 | 0.01 |

*The activities listed in Table 1 are included here only if total R2 > 0.20 and if more than 70% of the patients received the treatment activity.

†Independent variables allowed into models: age at injury, male, married, race-white, race–black, race–Hispanic, race – other, admission FIM motor score, admission FIM cognitive score, severity of illness score (CSI), injury group: C1–C4 ABC, injury group: C5−C8 ABC, injury group: Para ABC, injury group: AIS D, clinician experience, traumatic etiology – vehicular, traumatic etiology – violence, traumatic etiology – falls, traumatic etiology – sports, traumatic etiology-medical/surgical complication, traumatic etiology – other, work-related injury, number of days from trauma to rehabilitation admission, BMI >40, BMI 30−40, BMI <30, language – English, language – no English, language – English sufficient for understanding, payer – Medicare, payer-worker compensation, payer – private, payer – Medicaid, employment status at time of injury – employed, employment status at time of injury – student, employment status at time of injury – retired, employment status at time of injury – unemployed, employment status at time of injury – other, ventilator use at rehabilitation admission.

Discussion

Treatment variation by injury group

The SCIRehab TR taxonomy includes activities TRs use to engage patients in reentry to community activities and active participation in areas of interest. We found large variation in time spent for the sample as a whole and within neurologic injury groups. Several patient and injury characteristics explained some of this variation, as shown in Table 3, and may influence the types of TR services provided. Patients in the C1–C4: ABC injury group appear to spend more time in community outings compared to patients in other injury groups. However, the focus of rehabilitation for patients with high tetraplegia who generally have more involved care needs often is oriented toward family training and the patient's verbalization of personal care needs to maximize opportunities for reintegration into community life. Community outings provide these patients with the opportunity to practice verbalizing and directing their care, and to interact with community members who may be unfamiliar with disability issues. Crawford and Godbey38 describe barriers to leisure participation that include skill limitations, negative attitudes, dependence on others, poor communication, architectural/physical obstacles, financial restrictions, and lack of transportation. These barriers are paramount for patients with high tetraplegia, who, in addition, have needs associated with wheelchair driving, personal care, and adaptive equipment. Training in wheelchair navigation and performance of personal care in the community setting is a time-intensive process. Mastering the skills required for driving a chair using sip-n-puff or head-drive technology, for example, takes time, and often these chairs are set to operate at low speeds during the learning process, which means it takes longer to get from point A to point B. Personal care needs can consume large amounts of time and respiratory needs must be addressed during the community outing. One of the SCIRehab centers has a specialized program for such patients with C1–C4 injuries, which provides opportunities for weekly outings. Thus, study patients from this center may have been participating in the weekly ‘high-tetra program’ outings in addition to regular community outings with other patients.

The decreased motor function of patients with high tetraplegia limits their ability to participate in most leisure skill activities. There are assistive devices such as mouth sticks, bookstands, automatic page turners, button or sip and puff switches, and voice-activated software that enable individuals with little to no upper extremity movement to participate in some leisure skills. Advances in technology such as touch screens and e-book readers have opened up additional possibilities when combined with traditional assistive devices. The focus of leisure skill training with patients with high tetraplegia is providing education on available options and equipment. More advanced technology is often cost prohibitive. CTRSs initiate an assertive approach to funding, such as fundraisers, supportive family and friends, and seeking grants through various organizations.

Patients in the AIS D group on average have a smaller number of total TR hours, and a smaller average number of TR minutes of treatment per week, than the three other categories. The former is linked to their shorter LOS (36 days, on average, compared to 60 days for the three other groups combined) and presumably to their lesser need for TR services as indicated by fewer minutes per average week. They require little to no adapted equipment, and thus, are able to return to their previous levels of leisure involvement with little compensatory training. Additionally, patients in the AIS D injury group who are able to ambulate tend to go out of the rehabilitation center with their families to eat out or participate in community events more often than patients adjusting to use of a wheelchair for mobility. However, AIS D patients still receive a standard initial assessment, and TR specialists discuss these patients during the SCI team interdisciplinary conferences. Because the admission and discharge conference tend to be lengthy, they weigh relatively heavy in a short LOS. Thus, it is not surprising that the AIS D patients got on average as much (or nearly as much) total time spent on initial assessment (0.3 hours) or interdisciplinary conferencing (1.6 hours) as the three other injury groups, but more time per week, while of all other TR services they received fewer total hours and a smaller number of minutes per week.

Social events such as holiday meals and parties, concerts, karaoke, ‘fun food’ nights, visits from prominent athletes, cheerleaders, and performers, as well as the spontaneous social interactions among patients and families that occur during these events, provide patients with valuable opportunities for problem solving, brainstorming, and confidence building, while providing a bonding experience among patients and families. The value and healing benefits of social connections are extremely important to recovery from traumatic injuries. Thus, even though the TR taxonomy did not include a method to quantify these experiences in terms of time spent, clinicians place high value on their occurrence, and thus, participation in hospital-organized social events was documented as one of the critical TR activities.

We conducted regression analyses to examine patient and injury characteristics associated with time spent in specific TR activities. Our goal was not to compare one center to another, and thus, center identities were not entered into these models (using dummy coding). However, the large variability in the amount of time CTRSs spent with patients with SCI, both within and among injury categories, is not explained to any significant degree by demographic and clinical characteristics of patients, at least not the ones considered here, and we acknowledge that center differences may influence the amount of time spent on TR activities. Indeed, when center identities were allowed to enter the two regression models reported here (time spent in leisure skills in center and in leisure education and counseling), the explanatory power more than doubled. The R2 for the model predicting time spent in leisure skills in center increased from 0.21 to 0.46 and for time spent in leisure education and counseling from 0.22 to 0.54.

We acknowledge there are multiple differences in rehabilitation center practices that may influence time spent in TR in general and in specific TR activities. While community reintegration is a primary goal for TR in physical rehabilitation, only about 75% of SCIRehab patients participated in community outings. The regression model predicting time spent in all types of community outings led by TR did not meet our reporting threshold of having an R2 value of at least 0.20 (the R2 was only 0.14); however, when center identity was allowed to enter the model, the predictive value doubled to 0.28. Community reintegration involves two main components: leisure counseling to discuss self-advocacy, accessibility issues, problem solving techniques, social skills, transportation, and personal care in the community; and the actual community outing to practice all of these reintegration skills. The resources needed to take patients outside of the rehabilitation center include a suitable number of staff, appropriately trained staff, an outing budget that includes adequate monetary resources to pay for patient activities (food, transportation, admission/activity fees, etc.), availability of transportation, safe destinations in the community to go to, and administrative policies that support community outings.

The length of the rehabilitation stay also may influence the number of patients who participate in community re-entry and the frequency with which they are able to participate. Receipt of TR services for only a small number of weeks provides fewer opportunities to participate in community events, and rehabilitation centers with a lower average LOS may prioritize the limited time their CTRSs have to providing as much leisure counseling and resource acquisition as possible prior to discharge. Some patients may have a shorter LOS because they have fewer needs. For those patients who had a shorter LOS for other reasons, prioritizing would mean that some goals would not be addressed as therapists focused on basic needs to prepare a patient for discharge.

Study limitations

SCIRehab facilities offer variation in setting, care delivery patterns, and patient clinical and demographic characteristics and were selected to participate based on their willingness, geographic diversity, and expertise in treatment of patients with SCI. Thus, these centers are not a probability sample of the rehabilitation facilities that provide care for patients with SCI in the United States and time reported on specific activities may not be generalizable to all rehabilitation centers.

Study data are only as complete as the data entered by each CTRS for each patient interaction. Study coordinators at each project site compared project documentation with billing records and patient schedules to ensure that documentation was as complete as possible. However, many TR activities are not billable and thus, billing records were not helpful in this comparison. The dynamic nature of patient schedules makes them another unreliable source for comparison. Therefore, it is possible that some TR intervention time may not have been included. Of the 600 patients, 94% were reported to have received one or more TR treatment sessions during their rehabilitation stay. Non-receipt of services may have been due to a long-standing TR vacancy at one of the smaller centers and idiosyncratic reasons in a few other instances; it would therefore seem unlikely that these 6% of patients did not receive services, but none of them were reported on POC forms.

Conclusion

Most patients with SCI received some TR during their inpatient rehabilitation and about 75% of patients participated in at least one structured therapeutic outing. The large amount of variability seen in TR treatment time within and among injury group categories, which is not explained well by patient and injury characteristics, sets the stage for future analyses to associate treatments with outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The contents of this paper were developed under grants from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Department of Education, NIDRR grant nos. H133A060103 and H133N060005 to Craig Hospital, H133N060028 to National Rehabilitation Hospital, H133N060009 to Shepherd Center, and H133N060027 to the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. The opinions contained in this publication are those of the grantees and do not necessarily reflect those of the US Department of Education.

References

- 1.Schönherr M, Groothoff J, Mulder G, Eisma W. Participation and satisfaction after spinal cord injury: Results of a vocational and leisure outcome study. Spinal Cord 2005;43(4):241–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pentland W, Harvey A, Smith T, Walker J. The impact of spinal cord injury on men's time use. Spinal Cord 1999;37(11):786–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yerxa E, Locker S. Quality of time use by adults with spinal cord injuries. Am J Occup Ther 1990;44(4):318–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasiemski T, Kennedy P, Gardner B, Taylor N. The association of sports and physical recreation with life satisfaction in a community sample of people with spinal cord injuries. NeuroRehabilitation 2005;20(4):253–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson K, Klaas S. The changing nature of play: Implications for pediatric spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2007;30Suppl 1:S71–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu M, Chan F. Psychosocial adjustment patterns of persons with spinal cord injury in Taiwan. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29(24):1847–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bénony H, Daloz L, Bungener C, Chahraoui K, Frenay C, Auvin J. Emotional factors and subjective quality of life in subjects with spinal cord injuries. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2002;81(6):437–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown M, Gordon W, Spielman L, Haddad L. Participation by individuals with spinal cord injury in social and recreational activity outside the home. Top Spinal Cord Injury Rehabil 2002;7(3):83–100 [Google Scholar]

- 9.McVeigh S, Hitzig S, Craven B. Influence of sport participation on community integration and quality of life: a comparison between sport participants and non-sport participants with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(2):115–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleiber D, Brock S. The relevance of leisure in an illness experience: Realities of spinal cord injury. J Leis Res 1995;27:283–99 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boschen K, Tonack M, Gargaro J. Long-term adjustment and community reintegration following spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res 2003;26(3):157–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchholz A, Martin Ginis K, Bray S, Craven B, Hicks A, Hayes K, et al. Greater daily leisure time physical activity is associated with lower chronic disease risk in adults with spinal cord injury. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2009;34(4):640–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slater D, Meade M. Participation in recreation and sports for persons with spinal cord injury: review and recommendations. NeuroRehabilitation 2004;19(2):121–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arbour-Nicitopoulos K, Ginis K, Latimer A. Planning, leisure-time physical activity, and coping self-efficacy in persons with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90(12):2003–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy P, Lude P, Taylor N. Quality of life, social participation, appraisals and coping post spinal cord injury: a review of four community samples. Spinal Cord 2006;44(2):95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniel A, Manigandan C. Efficacy of leisure intervention groups and their impact on quality of life among people with spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res. 2005;28(1):43–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noreau L, Fougeyrollas P. Long-term consequences of spinal cord injury on social participation: the occurrence of handicap situations. Disabil Rehabil 2000;22(4):170–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noreau L, Shephard R. Relationship of impairment and functional ability to habitual activity and fitness following spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res 1993;16(4):265–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keogh Hoss M, McCormick B. Survey to identify quality indicators for recreational therapy practice. Annu Therap Recreation 2007;15:35–44 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whiteneck G, Gassaway J, Dijkers M, Charlifue S, Backus D, Chen D, et al. SCIRehab: inpatient treatment time across disciplines in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med 2011;34(2):135–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteneck G, Dijkers M, Gassaway J, Jha A. SCIRehab: New approach to study the content and outcomes of spinal cord injury rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(3):251–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gassaway J, Whiteneck G, Dijkers M. SCIRehab: clinical taxonomy development and application in spinal cord injury rehabilitation research. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(3):260–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horn S, Gassaway J. Practice-based evidence study design for comparative effectiveness research. Med Care 2007;45Suppl 2:S50–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeJong G, Hsieh C, Gassaway J, Horn S, Smout R, Putman K, et al. Characterizing rehabilitation services for patients with knee and hip replacement in skilled nursing and inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90(8):1284–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gassaway J, Horn S, DeJong G, Smout R, Clark C, James R. Applying the clinical practice improvement approach to stroke rehabilitation: methods used and baseline results. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;8612 Suppl 2:S16–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horn S, DeJong G, Ryser D, Veazie P, Teraoka J. Another look at observational studies in rehabilitation research: going beyond the holy grail of the randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;8612 Suppl 2:S8–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marino R. ed. Reference manual for the international standards for neurological classification of SCI. Chicago, IL: American Spinal Injury Association; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horn S, Sharkey S, Rimmasch H. Clinical practice improvement: a methodology to improve quality and decrease cost in health care. Onc Issues 1997;12(1):16–20 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horn S, Sharkey P, Buckle J, Backofen J, Averill R, Horn R. The relationship between severity of illness and hospital length of stay and mortality. Med Care 1991;29(4):305–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryser D, Egger M, Horn S, Handrahan D, Ghandi P, Bigler E. Measuring medical complexity during inpatient rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86(6):1108–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Averill R, McGuire T, Manning B, Fowler D, Horn S, Dickson P, et al. A study of the relationship between severity of illness and hospital cost in New Jersey hospitals. Health Services Res 1992;27(5):587–617 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clemmer T, Spuhler V, Oniki T, Horn S. Results of a collaborative quality improvement program on outcomes and costs in a tertiary critical care unit. Crit Care Med 1999;27(9):1768–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiedler R, Granger C. Functional independence measure: a measurement of disability and medical rehabilitation. In: Chino N, Melvin J. (eds.) Functional evaluation of stroke patients. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; 1996. p. 75–92 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiedler R, Granger C, Russell C. UDS(MR)SM: follow-up data on patients discharged in 1994–1996. Uniform data system for medical rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2000;79(2):184–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cahow C, Skolnick S, Joyce J, Jug J, Dragon C, Gassaway J. SCIRehab: the therapeutic recreation taxonomy. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(3):297–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens J. Intermediate statistics: a modern approach. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens J. Partial and semipartial correlations. 2003. [accessed 2010 Feb 10]. Available from: www.uoregon.edu/~stevensj/MRA/partial.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crawford D, Godbey G. Reconceptualizing barriers to family leisure. Leis Sci 1987;9:119–27 [Google Scholar]