Abstract

Background

Nurses are an integral part of the spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation team and provide significant education to the patient and family about the intricacies of living with SCI, as well as help manage the care process.

Objective

This is the second in a series of reports by clinical nursing leaders involved in the SCIRehab research project, a multi-center, 5-year study to record and analyze details of SCI inpatient rehabilitation, with focus on descriptions of time spent by nurses on bedside education and care management.

Methods

Six hundred patients with traumatic SCI were enrolled at six rehabilitation centers. Nurses providing usual care to patients with SCI documented the content and amount of time spent on each bedside interaction using portable electronic devices with customized software or a newly developed customized page in electronic documentation systems; this included details of education or care management. Patient and injury characteristics, including level and nature of injury, were taken from the medical record.

Results

Nursing data for this report were derived from 42 048 shifts of nursing care. The mean total of nursing education and care management per patient was 30.6 hours (range 1.2–126.1, standard deviation (SD) 20.7, median 25.5). The mean number of minutes per week was 264.3 (range 33.2–1253, SD 140.9, median 241.9). The time that nurses spent on each activity was significantly different in each neurological injury group. Fifty percent of care management time was devoted to psychosocial support, while medication, skin care, bladder, bowel, and pain management were the main education topics.

Conclusions

Nurses in SCI rehabilitation spend a significant amount of time providing education and psychosocial support to patients and their families. Typically, this is not included in traditional documentation systems. Quantification of these interventions will allow researchers to discern whether there are pertinent associations between the time spent on bedside activities and patient outcomes. The data will also be relevant for patient care planning and acuity staffing.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries, Rehabilitation, Health services research, Nursing, Paraplegia, Tetraplegia

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation is a specialty area that relies heavily on an interdisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, psychologists, therapists, and nutritionists to provide optimum care for patients. While the team works collaboratively to achieve patient and family goals, each discipline provides unique contributions to patient care, which, in turn, may significantly impact outcomes. In addition to participating in aspects of care management such as providing psychosocial support, discharge planning, and consulting with other caregivers (team process), an important role for nursing staff is educating patients and family members about the physiologic changes that occur as a result of a traumatic SCI. For example, urinary complications affect independent function and quality of life in patients with SCI; therefore, education and awareness of such changes should be addressed during the rehabilitation process to promote healthy function of the urinary system. This education process ideally begins in the acute care setting, and is followed by much emphasis and refinement during the rehabilitation phase where the patient is able to participate actively.

There is a large body of literature related to rehabilitation nursing care of patients with SCI; however, little research focuses on how this care may influence outcomes, such as length of stay (LOS), complications, and quality of life. As part of its practice guidelines, the Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine, identified four domains of outcomes for patients with traumatic SCI: motor recovery, functional independence, social integration, and quality of life.1 Nursing interventions likely influence the domains of functional independence, social reintegration, and quality of life.

Outcomes of nursing practice were described by Ralph et al.2 as those that could be linked to specific structural or procedural nursing-sensitive interventions. They also suggest that measuring nurse-sensitive outcomes may lead to improving patient care. During the planning stages of Ralph's study, bowel and bladder elimination were ranked as the top two nurse-sensitive outcomes by experienced SCI nurse clinicians, followed by ambulation and tissue integrity. Nursing contributions to the rehabilitation process may be undervalued by patients, who, in a recent study, reported thinking that nurses provide emotional and physical support but have a lesser role in the rehabilitation process than other disciplines that provide ‘therapy’.3 Nevertheless, nurses were viewed as the first point of contact and as the clinicians who provide information most relevant to their patients' recovery.

Patient education has been studied within the domains of knowledge, problem-solving, and perceived importance of the information that is taught. May et al.4 concluded that the acquisition of knowledge did not translate into better problem-solving capabilities even though a patient may perceive a topic as important. Individual interactions may be more effective than traditional classes for the adult learner. Through direct teaching with the patient and family, nurses are able to focus on areas of importance for community reentry, e.g. bowel and bladder management training and skin integrity maintenance.

This paper is the second in a series of reports by clinical nursing leaders involved in the SCIRehab research project.5–7 SCIRehab is a multi-center, 5-year study that will enroll approximately 1400 acute SCI inpatient rehabilitation patients, record and analyze details of the rehabilitation process, and determine whether type and quantity of nursing interventions (along with interventions provided by other rehabilitation care providers) are predictive of first-year post-injury outcomes. The study design and implementation of the practice-based evidence (PBE) research methodology used in SCIRehab have been described previously.5–7 For the nursing component of this study, nursing leaders from six SCI rehabilitation centers hypothesized that patient outcomes are influenced by the amount of nursing education and care management that is provided to the patient and/or designated family caregivers during the acute rehabilitation period. The ultimate aim of the SCIRehab project is to test this hypothesis by examining details of specific components (interventions) provided within the rehabilitation nursing process. Quantifying time spent on patient and family education is perhaps unique to this project's nursing documentation as nurses traditionally document that education has been completed, but do not quantify the amount of time spent on specific topics. All patients do receive education and prove competence in specific areas to ensure a safe discharge. However, content does vary by injury level, and the time needed to achieve competence has not been studied. This paper aims at describing the content and amount of time spent on bedside education and care management activities (discharge planning, team process, and psychosocial support) that were documented by SCIRehab center's nurses and identifying patient and injury characteristics associated with time spent on these activities.

Methods

The introductory paper8 to this series describes the SCIRehab project's design, including use of PBE research methodology,5,6,9–12 inclusion criteria, data sources, and the analysis plan. To summarize, the SCIRehab team included representatives from nursing and all major rehabilitation disciplines from six inpatient rehabilitation facilities: Craig Hospital, Englewood, CO; Shepherd Center, Atlanta, GA; Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Carolinas Rehabilitation, Charlotte, NC; The Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY; and National Rehabilitation Hospital, Washington, DC. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained at each center; the study enrolled patients who were 12 years of age or older, gave (or whose parent/guardian gave) informed consent, and were admitted to the facility's SCI unit for initial rehabilitation following traumatic SCI.

Patient/injury and clinician data

Trained data abstractors collected patient and injury data from patient medical records. The International Standards of Neurological Classification of SCI and its American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS)13 were used to describe the motor level and completeness of SCI. The Comprehensive Severity Index (CSI®) provided a measure of the medical severity of illness; a higher CSI score indicates a ‘sicker’ patient based on physiological symptoms documented for each of a patient's diseases, including comorbidities, at the time of rehabilitation admission and again for the full rehabilitation stay.14–18 The Functional Independence Measure (FIM®) was used to describe a patient's independence in specific motor and cognitive abilities at rehabilitation admission and discharge.19,20 Nurses who documented treatment data for the SCIRehab project completed a clinician profile that included their years of SCI rehabilitation experience at the start of the project.

The following categories for body mass index (BMI) were used: morbidly obese (>40 kg/m2), obese (30–40), and <30, which include the standard underweight, normal, and overweight categories. These categories were selected to focus on obesity and morbid obesity as they may have a substantial impact on rehabilitation interventions.

Nursing bedside education and care management data

Nursing leaders acknowledged that teaching done at the bedside, along with care management interventions and participation in interdisciplinary conferences on behalf of the patient, typically is not included in traditional nursing documentation. In order to capture these components of the nursing process they chose to isolate them for inclusion in supplemental documentation. Other components of the nursing care process were abstracted from traditional documentation systems at each SCIRehab facility. Nurses at the SCIRehab project sites entered details of bedside education and care management interactions with each study patient into either (1) a handheld personal digital assistant (PDA; Hewlett Packard PDA hx2490b, Palo Alto, CA) containing a modular custom application (PointSync Pro version 2.0, MobileDataforce, Boise, ID, USA) of the SCIRehab point-of-care documentation system, which incorporates the supplemental nursing taxonomy, or (2) a supplemental electronic page that included the taxonomy added to the existing electronic health record of the hospital. This taxonomy has been described in detail previously7 and included education topics and care management processes. Education topics included bladder management, bowel management, medical complications, medication, nutrition, pain, respiratory, safety, skin, and therapy carryover (reinforcing techniques learned during therapy sessions). Care management foci included providing psychosocial support, and planning for discharge. In addition, time was documented for organized classes led by nursing and for the time nurses spent in interdisciplinary conferences and ‘team process’ (care planning with other care providers, e.g. physicians, therapists, and nursing aides) on the patient's behalf.

The date and start time of each nursing shift, topic of education or care management, number of minutes (using 10-minute increments) spent, and who was involved in the interaction (patient, family/caregiver, or both) were entered into the PDA or supplemental electronic documentation. Also entered was the nurse's perception of the level of patient engagement in rehabilitation activities during the shift. Each nurse was trained on use of the documentation system at their center; quarterly testing using written case scenarios ensured inter-rater reliability. Education performed in less than 10-minute increments was not captured.

Data analysis

Analyses reported here include data for the patients enrolled in the SCIRehab project's first year. Patients with AIS grade D were grouped together regardless of injury level. Patients with AIS classifications of A, B, and C were grouped together and separated by motor level to determine the remaining three injury groups: C1–C4, C5–C8, and paraplegia (T1 and below).

Time spent in nursing bedside education and care management was quantified by summing the total number of minutes spent each shift during the rehabilitation stay. Because total time correlates highly with LOS in the rehabilitation center, we also calculated the average minutes per week as the primary measure of intensity. Contingency tables/chi-square tests and analysis of variance were used to test differences across injury groups for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. (A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.)

We used ordinary least squares stepwise-regression models to associate time spent on nursing education and care management processes in which at least 70% of patients participated, with patient and injury characteristics. The strength of the model is determined by the R2 value, which indicates the amount of variation explained by the significant variables. Type II semi-partial correlation coefficients allow for estimation of the unique contribution of each predictor variable after controlling for all other variables in the model.21,22 The parameter estimates indicate the direction and strength of the association between each independent variable with the dependent variable.

The patient/injury characteristics used included gender, marital status, racial/ethnic group, traumatic SCI etiology, BMI, English-speaking status, third-party payer, pre-injury occupational status, CSI score, age at the time of injury, admission FIM scores, experience level of the clinician, and injury grouping.

Results

Details of patient demographic and injury characteristics are presented for the sample as a whole and for each of the four injury groups separately in the first article in this SCIRehab series (Table 1).8 The sample was 81% male, 65% white (22% black), 38% married, and mostly not obese (82% had a BMI of <30). Sixty-five percent were employed at the time of injury. The average age was 37 years, with a standard deviation (SD) of 17. Vehicular accidents were the most common cause of injury (49%), falls were next (23%), followed by etiologies of sports (12%) and violence (11%); the remaining 5% were classified as other. The mean rehabilitation LOS was 55 days (range 2–259, SD 37, median 43). The mean total FIM score at admission was 53 (motor score of 24 and cognitive score of 29), and a mean of 32 days elapsed from the time of injury to the time of rehabilitation admission.

Table 1.

Nursing activities: percent of patients receiving each type of activity, mean minutes/week (SD), and mean total hours (SD), by neurological category*

| Full SCIRehab sample | C1–C4 AIS A, B, C | C5–C8 AIS A, B, C | Para AIS A, B, C | AIS D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 600 | n = 132 | n = 151 | n = 223 | n = 94 | |

| All nursing education and care management interventions (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Minutes per week (SD) | 264.3 (140.9) | 260.3 (131.3) | 267.9 (141.1) | 274.9 (152) | 239.2 (124.2) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 30.6 (20.7) | 40.0 (22.7) | 36.7 (20.3) | 26.3 (17.8) | 17.9 (14.7) |

| Education — all (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Minutes per week (SD)† | 193.8 (114.1) | 184.3 (106.3) | 196.4 (109.5) | 207.9 (124.7) | 169.3 (101.4) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 21.5 (13.5) | 26.4 (13.2) | 26.4 (14.9) | 19.1 (11.1) | 12.5 (10.8) |

| Bladder (%) | 97 | 97 | 100 | 98 | 88 |

| Minutes per week (SD)† | 33.8 (29.5) | 23.1 (21.7) | 34.3 (27.0) | 40.6 (31.5) | 32.2 (33.6) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 3.5 (2.8) | 3 (2.2) | 4.4 (3.1) | 3.6 (2.5) | 2.6 (3.2) |

| Bowel (%) | 98 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 88 |

| Minutes per week (SD)† | 30.7 (25.9) | 22.9 (20.3) | 30.4 (21.4) | 37.9 (30.5) | 24.9 (23.2) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 3.1 (2.5) | 2.9 (2.4) | 4.0 (3.0) | 3.1 (2.2) | 1.8 (2.1) |

| Complications (%) | 90 | 99 | 95 | 89 | 67 |

| Minutes per week (SD)† | 12.7 (12.0) | 16 (12.9) | 15.3 (12.2) | 11.5 (11.6) | 6.8 (8.5) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 1.7 (2) | 2.6 (2.2) | 2.3 (2.1) | 1.2 (1.6) | 0.6 (0.8) |

| Medication (%) | 100 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Minutes per week (SD) | 27.5 (22.3) | 27.1 (21.8) | 28.1 (22.3) | 27.5 (23.5) | 27.1 (20.1) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 2.8 (2.3) | 3.5 (2.2) | 3.5 (2.7) | 2.4 (1.9) | 1.9 (1.9) |

| Nutrition (%) | 82 | 93 | 91 | 78 | 64 |

| Minutes per week (SD)† | 8 (10.6) | 10.7 (12.6) | 9.5 (11.3) | 6.4 (9.1) | 5.7 (7.9) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 0.9 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.5) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.8) |

| Pain (%) | 96 | 98 | 99 | 96 | 88 |

| Minutes per week (SD) | 26.5 (26.8) | 25.0 (24.1) | 23.9 (26.1) | 29.8 (29.7) | 25.0 (23.9) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 2.8 (2.8) | 3.5 (3.2) | 3 (2.8) | 2.7 (2.7) | 1.7 (2.0) |

| Respiratory (%) | 51 | 78 | 66 | 34 | 32 |

| Minutes per week (SD)† | 6.1 (14.7) | 15.2 (24.6) | 6.4 (11.3) | 2.3 (7.4) | 2.0 (5.9) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 0.9 (2.3) | 2.3 (3.8) | 1.0 (2.4) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.6) |

| Safety (%) | 89 | 89 | 92 | 93 | 77 |

| Minutes per week (SD)† | 10.4 (10.8) | 8.5 (10.1) | 10.0 (10.3) | 10.8 (10.8) | 12.8 (12.1) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.3) | 0.9 (0.9) | 0.9 (1) |

| Skin (%) | 98 | 100 | 99 | 98 | 89 |

| Minutes per week (SD) | 26.9 (24.5) | 26.5 (18.5) | 27.8 (21.6) | 28.5 (29.8) | 22.2 (22.1) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 3.1 (2.9) | 3.9 (2.7) | 3.8 (3.2) | 2.8 (2.8) | 1.5 (1.8) |

| Therapy carryover (%) | 56 | 62 | 66 | 50 | 41 |

| Minutes per week (SD) | 3.8 (9.3) | 3.1 (5) | 3.7 (8.2) | 4.3 (12.2) | 3.5 (7.3) |

| Total hours (SD) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.2 (0.5) |

| SCI classes led by nursing (%) | 39 | 41 | 40 | 40 | 29 |

| Minutes per week (SD) | 7.4 (12.4) | 6.2 (10.0) | 7.1 (10.9) | 8.4 (13.8) | 7.2 (14.3) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 1.2 (2.0) | 1.5 (2.3) | 1.3 (2.2) | 1.1 (1.9) | 0.7 (1.4) |

| Care management — all (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Minutes per week (SD)† | 70.6 (45.1) | 76 (48.1) | 71.5 (44.3) | 67.1 (45.7) | 69.9 (40.3) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 9.1 (9.6) | 13.6 (13) | 10.3 (7.6) | 7.2 (8.7) | 5.4 (5.3) |

| Psychosocial support (%) | 90 | 95 | 93 | 89 | 80 |

| Minutes per week (SD)† | 34.7 (37.5) | 42 (42.5) | 37.8 (39) | 31.3 (35.2) | 27.5 (30.4) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 4.4 (6.2) | 6.9 (9) | 5.1 (5.3) | 3.2 (5) | 2.3 (3.2) |

| Discharge planning and management (%) | 84 | 89 | 88 | 83 | 76 |

| Minutes per week (SD) | 8.8 (11.2) | 7.7 (7.5) | 7.5 (9.1) | 9.5 (12.4) | 10.6 (14.9) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 0.9 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.5) | 0.9 (0.9) | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.6 (0.7) |

| Team process participation (%) | 56 | 66 | 60 | 55 | 40 |

| Minutes per week (SD) | 4.5 (8.4) | 5.0 (7.7) | 4.2 (6.3) | 4.3 (7.8) | 4.5 (12.5) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 0.7 (1.5) | 1.0 (1.9) | 0.7 (1.1) | 0.6 (1.6) | 0.3 (0.8) |

| Interdisciplinary conferencing on patient's behalf (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Minutes per week (SD)† | 22.6 (16.5) | 21.2 (12.3) | 22.0 (16.0) | 22 (16.5) | 27.3 (21.3) |

| Total hours (SD)† | 3.2 (3.3) | 4.3 (4.0) | 3.6 (3.3) | 2.6 (2.9) | 2.1 (2.2) |

*Total hours and minutes per week are averages over all 600 patients, not just based on those who did receive one or more sessions of a particular activity.

†Statistically significant differences in time spent (total hours or minutes per week) among groups.

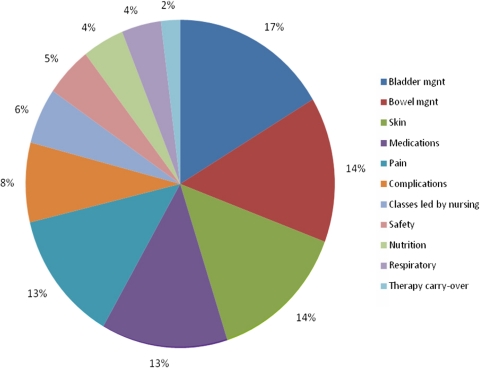

Nurses documented information for 42 048 shifts for the 600 SCIRehab patients who received a mean total of 31 hours (range 1–126, SD 21, median 26) of nursing education and care management. The total mean hours over the full rehabilitation stay within these activities and the average number of minutes per week for the full sample and for the four injury groups separately are shown in Table 1. The mean number of minutes per week for the full sample was 264 (range 33–1253, SD 141, median 242). Significant differences were seen in the amount of time spent in each activity among the four injury groups. Bladder management was the education topic that comprised the largest proportion of time (17% of total time), next were bowel management and skin (14% each), and medication and pain education (13% each) (Fig. 1). About 50% of all care management time in all injury groups was spent on psychosocial support of the patient and/or family.

Figure 1.

Nursing education topic frequency — percentage of total hours; n = 600 patients.

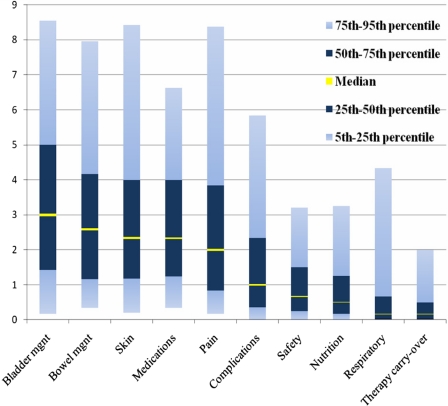

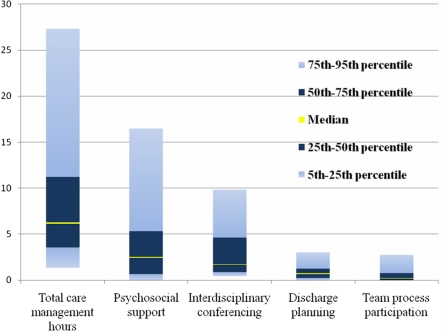

Fig. 2 depicts the variation in total hours during rehabilitation spent within each nursing education topic for the entire SCIRehab sample. For bladder management education, the interquartile range (IQR) was 1.3–5 hours (median 3 hours), for bowel management the IQR was 1.2–4.2 (median 2.6 hours), and for skin, medication, and pain education the IQR was approximately 1–4 (median about 2 hours). Fig. 3 depicts similar variation in time spent on care management; the IQR for psychosocial support was 0.7–5.3 hours with a median of 2.5 hours.

Figure 2.

Variation in time spent on nursing education topics (total hours), n = 600 patients.

Figure 3.

Variation in time spent on nursing care management (total hours), n = 600 patients.

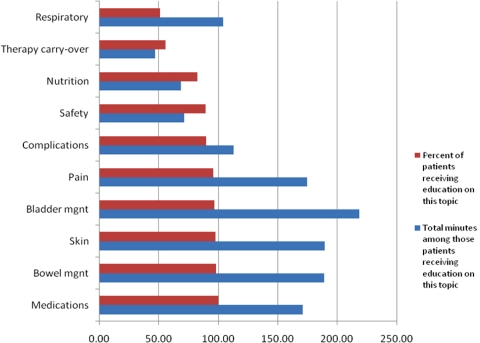

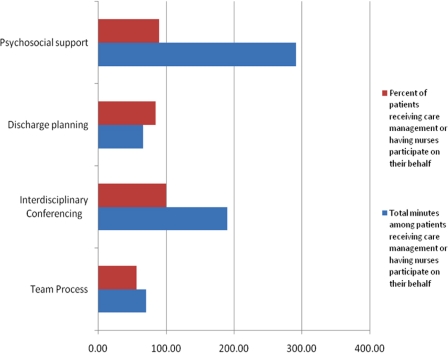

Fig. 4 displays the percentage of patients who received each topic included in the education portion of the supplemental nursing taxonomy and the mean number of minutes during rehabilitation spent on each topic, for these patients only. Fig. 5 shows similar information for care management. For example, almost all patients received education for bowel and bladder management, skin, and pain, as well as psychosocial support (care management). However, the greatest amount of time was spent on psychosocial support (291 total minutes (4.8 hours over the entire stay, on average)) and bladder management (220 total minutes (3.6 hours)). While only about half of the patients received education about respiratory issues, these patients spent a mean of more than 100 minutes on this topic.

Figure 4.

Percent of patients receiving education on each of 10 topics and minutes during the entire rehabilitation stay average for these patients.

Figure 5.

Percent of patients receiving nursing care management in discharge planning and psychosocial support and nursing participation in team process and interdisciplinary conferencing on behalf of the patient and total minutes during rehabilitation spent among patients within each area.

Patient and injury characteristics that were associated with time (minutes per week) spent on the nursing education topic of bladder management and with time nurses spent in interdisciplinary conferences are reported in Table 2. Other education topics and care management processes did not have at least 70% of patients participate, or the regression model did not explain more than 20% of the total variance (as determined by the R2 value). The parameter estimates indicate the direction and strength of the association between each independent variable with the dependent variable. The type II semi-partial R2 estimates the unique contribution of each predictor variable.

Table 2.

Patient and injury characteristics associated with time (minutes/week) in nursing activities*,†

| Bladder education |

Interdisciplinary conferencing |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total R2 = 0.21 |

Total R2 = 0.21 |

|||

| Independent variable | Parameter estimate | Type II semi-partial R2 | Parameter estimate | Type II semi-partial R2 |

| Race – white | 4.86 | 0.01 | −2.69 | 0.01 |

| Severity of illness score (CSI) | −0.26 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.07 |

| Admission FIM cognitive score | 0.61 | 0.04 | ||

| Injury group: C5–C8 ABC | 7.20 | 0.01 | ||

| Injury group: AIS D | 7.29 | 0.02 | ||

| Injury group: Para ABC | 11.42 | 0.03 | ||

| Clinician experience | 1.73 | 0.09 | ||

| Employment status at the time of injury – student | −6.31 | 0.01 | ||

| Employment status at the time of injury – other | 34.22 | 0.06 | ||

*Activities included only if more than 70% of patients participated and the total R2 > 0.20.

†Independent variables allowed into models: age at injury, male, married, race – white, race – black, race – Hispanic, race – other, admission FIM motor score, admission FIM cognitive score, severity of illness score (CSI), injury group: C1–C4 ABC, injury group: C5–C8 ABC, injury group: Para ABC, injury group: AIS D, clinician experience, traumatic etiology – vehicular, traumatic etiology – violence, traumatic etiology – falls, traumatic etiology – sports, traumatic etiology – medical/surgical complication, traumatic etiology – other, work-related injury, number of days from trauma to rehabilitation admission, BMI >40, BMI 30–40, BMI <30, language – English, language – no English, language – English sufficient for understanding, payer – Medicare, payer – worker compensation, payer – private, payer – Medicaid, employment status at the time of injury – employed, employment status at the time of injury – student, employment status at the time of injury – retired, employment status at the time of injury – unemployed, employment status at the time of injury – other, and ventilator use rehabilitation admission.

For bladder management education, the regression model explains 21% of the variation in time spent (R2 = 0.21). The parameter estimate for the CSI severity of illness score (independent variable) is −0.26, which indicates that for each additional severity point, 0.26 fewer minutes were spent on bladder education. Therefore, a patient with a severity score of 100 would be predicted to receive 26 fewer minutes per week of bladder education (parameter estimate of 0.26 × 100) and the semi-partial R2 indicates that this is the largest explanatory variable (its unique contribution is 9%). The parameter estimate for race/white is 4.86, indicating that Caucasians received an average of nearly 5 minutes per week more of bladder education than other races. Other variables associated with more time spent on bladder education included injury groups C5–C8 ABC and Para ABC, and employment status other (when compared to working, student, unemployed, and retired). Predictors of more time that nurses spent participating in interdisciplinary conferencing (R2 = 0.21) included higher CSI score, higher admission FIM cognitive score, injury group AIS D, and higher levels of clinical experience of the nurses providing the education (strongest predictor with semi-partial R2 of 0.09).

Discussion

We examined time spent on nursing bedside education and care management in two ways: total hours spent over the course of the rehabilitation stay and a calculated value of mean minutes per week. Reporting both total hours and minutes per week was necessary to overcome the effect of LOS on time spent on education. For example, the paraplegia group received fewer total hours of education over the course of the rehabilitation stay than the two tetraplegia groups; however, LOS typically is shorter for patients with paraplegia. This group actually spent more time per week in education than all other injury groups. We hypothesize the reason for these findings is that nurses identify the type and amount of education needed to accomplish discharge goals and fit the education into the time that is available, so patients with shorter lengths of stay may get more intense education in less time.

Psychosocial support for patients and their families emerged as the most common component of care management for all injury groups. Nurses spend a great deal of time providing support to patients and families; traditionally, however, this support is not considered in staffing plans or included in traditional documentation. The provision of psychosocial support is important and may contribute to improved patient outcomes. Decision makers who plan staffing for SCI rehabilitation units should consider time consumed for psychosocial support and apply sufficient weight in staffing and acuity systems to account for the formidable amount of time that nurses spend on this intervention.

The education topic that consumed the greatest percentage of nursing time was bladder education. We hypothesize that this may be due to the ongoing and frequent bladder management needs of patients with SCI. Rehabilitation nurses usually initiate and reinforce a bladder management plan of care in keeping with clinical practice guidelines23 and individual patient needs and preferences. This begins early in the rehabilitation process as indwelling urinary catheters often are removed soon after admission. Bladder management techniques require continuous practice by the patient and ongoing education of the patient and family throughout the rehabilitation stay. Urinary catheterization can be performed as frequently as every 4 hours, in contrast to a daily bowel program or twice-daily skin assessment. Patients may also be more motivated to practice and master catheterization techniques because being clean and free of incontinent episodes enhances self-image, improves self-worth and general health, as well as facilitates community reintegration.

Several predictors of time spent on bladder management education are logical; others may require more investigation. Injury group Para ABC was associated with more time spent on bladder management. Patients in this injury group are better able to master catheterization skills due to greater finger dexterity and function than patients with higher levels of injury. Thus, to master the skills needed for community reintegration, they may spend more time practicing. Patients with C1–C4 levels of injury may have spent less time on bladder management because independent catheterization may not have been a realistic goal; family members or caregivers of these patients are the ones who would be taught catheterization techniques and they tend to take less time to achieve proficiency. Patients in the C5–C8 injury group have impaired finger dexterity and hand function; membership in this injury group is a weaker (but significant) predictor of more nursing time spent in bladder education. (Occupational therapists also may work on bladder management with these patients as they provide assistive devices to facilitate hand function.) Being a student was associated with less nursing time spent on bladder management education. Students often are proficient learners and, because of high privacy needs at this stage of life, may be more motivated to achieve independence. Race as a significant predictor of time spent on any intervention is curious. While it is significant in the regression models reported here, its predictive power is weak (semi-partial R2 = 0.01). We will wait for data on our full SCIRehab sample before examining further.

A higher level of clinical experience was associated with more time spent in interdisciplinary conferences. We hypothesize that more experienced nurses may be in positions such as charge nurses or team leaders who routinely attend these conferences. Additionally, more experienced nurses may work the shift in which most of the conferencing is scheduled, typically the day shift.

We conducted regression analyses to examine patient and injury characteristics associated with time spent in specific activities. Typical PBE analytic strategies does not compare one center to another because it is thought that center effects may result from underlying differences in patient, injury, or clinician characteristic; and thus, center identities were not entered into these models. However, we acknowledge that there may be additional center-specific factors that may also influence the amount of time spent on specific areas of care management or bedside education. And, indeed, when centers were allowed to enter the two regression models reported here (time spent in bladder management education and time nurses spent in interdisciplinary conferencing), the explanatory power more than doubled. For bladder education, center effects added about 30% to the explained variation. The majority of the variance in interdisciplinary conferencing (66% added) may be due to substantial differences in how conferencing is conducted at various centers. These increases suggest that focusing on patient and injury characteristics may be supplemented with center effects to help explain variation in time spent in specific areas of teaching and care management work done with patients at the bedside. The significant variation in time spent should prove useful in the eventual effort to correlate interventions with key patient outcomes.

Limitations

Rehabilitation centers were selected to participate based on their willingness, geographic diversity, and expertise in the treatment of patients with SCI. These facilities offer variation in setting, care delivery patterns, and patient clinical and demographic characteristics; however, they are not a probability sample of the rehabilitation facilities that provide care for patients with SCI in the United States and time reported on specific activities may not be generalizable to all rehabilitation centers.

This study did not attempt to capture details, including time spent, on traditional ‘direct’ nursing care, e.g. treatment and medication administration, provision of daily care, etc.; and thus, the reader should not interpret these findings in the context of typical nursing hours per patient day. Some details of these other nursing duties were obtained by abstracting select pieces of information from traditional documentation but not at the level of detail that we studied time spent on bedside education and care management activities.

Since the study depended on the clinician documentation, some activities that occurred may not have been recorded. Nurses work a variety of shifts to provide adequate patient care; 24-hour staffing can consist of 4-, 8-, and 12-hour shifts in combinations that vary from day to day. Thus, it is difficult to know how often nurses were compliant in documenting project-specific information into their PDAs or supplemental electronic documentation. Education that was initiated by nurses on one shift and completed by nurses on the following shift may not have been documented in its entirety if the initiating nurse did not document her time. If nursing leaders varied in how much they stressed the importance of completing supplemental documentation, nursing staff may have had differing levels of understanding of its importance. However, with over 42 000 shifts included in the SCIRehab database, we believe that we captured a sufficient picture of care provided to determine the amount and variation of time spent on care management and educational topics. Additionally, education activities that take less than 10 minutes may be meaningful but would have been not captured and, thus, not reflected in our findings.

Conclusion

Rehabilitation nurses assume pivotal roles in educating patients with SCI and their families and caregivers. Training provided by rehabilitation nurses and the rest of the health-care team members during a patient's rehabilitation stay provides a solid foundation to maximize level of functioning and independence after discharge. Quantifying time spent on nursing education is not routine and perhaps unique to this study. Nurses spent the most time providing education on bladder management followed by bowel management, skin, medication, and pain education. This is not surprising to the nursing leaders who are expert rehabilitation nurses. What will be interesting to learn at the completion of this study is whether a specific threshold of time intensity in any category of nursing education is associated with optimal patient outcomes.

Psychosocial support comprised 50% of the care management time spent by rehabilitation nurses. Because psychosocial support may not be documented consistently or factored into staffing plans, this finding should be taken into consideration by decision makers in rehabilitation units. Does psychosocial support contribute to improved patient outcomes? We hope to answer this question in the final analysis of this study.

Acknowledgements

The contents of this paper were developed under grants from the Department of Education, NIDRR grant # H133A060103 and # H133N060005 to Craig Hospital, H133A21943-16 to Carolinas Rehabilitation, H133N060009 to Shepherd Center, and H133N060014 to Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago. The contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

References

- 1.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Outcomes following traumatic spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guidelines for healthcare professionals. J Spinal Cord Med 2000;23(4):289–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ralph S, Mailey S, Hayes K, Deneselya J, Kraft M, Bachand J. Validation of nursing sensitive outcomes in persons with spinal cord impairment. SCI Nurs 2003;20(4):251–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pellatt G. Perceptions of the nursing role in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Br J Nurs 2003;12(5):292–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.May L, Day R, Warren S. Evaluation of patient education in spinal cord injury rehabilitation: knowledge, problem-solving and perceived importance. Disabil Rehabil 2006;28(7):405–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gassaway J, Whiteneck G, Dijkers M. SCIRehab: clinical taxonomy development and application in spinal cord injury rehabilitation research. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(3):260–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whiteneck G, Dijkers M, Gassaway J, Jha A. SCIRehab: new approach to study the content and outcomes of spinal cord injury rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(3):251–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson K, Bailey J, Rundquist J, Dimond P, McDonald C, Reyes I, et al. SCIRehab: the supplemental nursing taxonomy. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(3):328–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiteneck G, Gassaway J, Dijkers M, Charlifue S, Backus D, Chen D, et al. SCIRehab: Inpatient treatment time across disciplines in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med 2011;34(2):135–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horn S, Gassaway J. Practice-based evidence study design for comparative effectiveness research. Med Care 2007;45(Suppl 2):S50–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeJong G, Hsieh C, Gassaway J, Horn S, Smout R, Putman K, et al. Characterizing rehabilitation services for patients with knee and hip replacement in skilled nursing and inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90(8):1284–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gassaway J, Horn S, DeJong G, Smout R, Clark C, James R. Applying the clinical practice improvement approach to stroke rehabilitation: Methods used and baseline results. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;8612 Suppl 2:S16–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horn S, DeJong G, Ryser D, Veazie P, Teraoka J. Another look at observational studies in rehabilitation research: Going beyond the holy grail of the randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;8612 Suppl 2:S8–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marino R. editor. Reference manual for the international standards for neurological classification of SCI. Chicago, IL: American Spinal Injury Association; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horn S, Sharkey S, Rimmasch H. Clinical practice improvement: a methodology to improve quality and decrease cost in health care. Oncol Issues 1997;12(1):16–20 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horn S, Sharkey P, Buckle J, Backofen J, Averill R, Horn R. The relationship between severity of illness and hospital length of stay and mortality. Med Care 1991;29(4):305–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryser D, Egger M, Horn S, Handrahan D, Ghandi P, Bigler E. Measuring medical complexity during inpatient rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86(6):1108–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Averill R, McGuire T, Manning B, Fowler D, Horn S, Dickson P, et al. A study of the relationship between severity of illness and hospital cost in New Jersey hospitals. Health Serv Res. 1992;27(5):587–617 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clemmer T, Spuhler V, Oniki T, Horn S. Results of a collaborative quality improvement program on outcomes and costs in a tertiary critical care unit. Crit Care Med 1999;27(9):1768–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiedler R, Granger C. Functional independence measure: a measurement of disability and medical rehabilitation. In: Chino N, Melvin J.(eds.) Functional evaluation of stroke patients. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; 1996. p. 75–92 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiedler R, Granger C, Russell C. UDS(MR)SM: follow-up data on patients discharged in 1994–1996. Uniform data system for medical rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2000;79(2):184–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens J. Partial and semipartial correlations; 2003. [accessed 2010 Feb 10]. Available from: www.uoregon.edu/~stevensj/MRA/partial.pdf

- 22.Stevens J. Intermediate statistics: a modern approach. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Bladder management for adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care providers. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29(5):527–73 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]