Abstract

Objective

To assess the prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors in Seychelles, a middle-income African country, and compare the cost-effectiveness of single-risk-factor management (treating individuals with arterial blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg and/or total serum cholesterol ≥ 6.2 mmol/l) with that of management based on total CV risk (treating individuals with a total CV risk ≥ 10% or ≥ 20%).

Methods

CV risk factor prevalence and a CV risk prediction chart for Africa were used to estimate the 10-year risk of suffering a fatal or non-fatal CV event among individuals aged 40–64 years. These figures were used to compare single-risk-factor management with total risk management in terms of the number of people requiring treatment to avert one CV event and the number of events potentially averted over 10 years. Treatment for patients with high total CV risk (≥ 20%) was assumed to consist of a fixed-dose combination of several drugs (polypill). Cost analyses were limited to medication.

Findings

A total CV risk of ≥ 10% and ≥ 20% was found among 10.8% and 5.1% of individuals, respectively. With single-risk-factor management, 60% of adults would need to be treated and 157 cardiovascular events per 100 000 population would be averted per year, as opposed to 5% of adults and 92 events with total CV risk management. Management based on high total CV risk optimizes the balance between the number requiring treatment and the number of CV events averted.

Conclusion

Total CV risk management is much more cost-effective than single-risk-factor management. These findings are relevant for all countries, but especially for those economically and demographically similar to Seychelles.

الملخص

الغرض

تقييم انتشار عوامل الاختطار القلبية الوعائية في سيشيل، وهي دولة أفريقية متوسطة الدخل، ومقارنة فعاليّة التكلفة بين التدبير العلاجي لعامل الاختطار الفردي (مثل معالجة الأفراد الذين يكون ضغط الدم الشرياني لديهم أكبر من أو يساوي 140/90 ملي متر زئبق و/أو يكون مستوى الكوليسترول المصلي لديهم أكبر من أو يساوي 6.2 ملي مول لكل لتر) في مقابل التدبير العلاجي المستند إلى الاختطار القلبي الوعائي الإجمالي (مثل معالجة الأفراد الذين يكون الاختطار القلبي الوعائي لديهم أكبر من أو يساوي 10% أو أكبر من أو يساوي 20%).

الطريقة

استُخدِم المخطط الأفريقي لانتشار عامل الاختطار القلبي الوعائي والتكهن بالاختطار لتقدير الاختطار لعشر سنوات للمعاناة بحدث قلبي وعائي مميت أو غير مميت بين الأفراد في عمر 40-64 سنة. واستخدمت هذه الأرقام للمقارنة بين التدبير العلاجي لعامل الاختطار الفردي والتدبير العلاجي للاختطار الإجمالي من حيث عدد الذين يحتاجون إلى العلاج لتفادي الحدث القلبي الوعائي وعدد الأحداث الكامنة التي يمكن تلافيها طوال 10 سنوات. وقد افتُرِض أن علاج المرضى الذين لديهم اختطار قلبي وعائي إجمالي (أكبر من أو يساوي 20%) يتكوّن من جرعة ثابتة من توليفة من عدة أدوية (متعددة الحبَّات). واقتصر تحليل التكلفة على المداواة.

النتائج

وجد الاختطار القلبي الوعائي أكبر من أو يساوي 10% و أكبر من أو يساوي 20% لدى 10.8% و 5.1% من الأفراد بالترتيب. وبالتدبير العلاجي لعامل الاختطار الفردي، احتاج 60% من البالغين إلى العلاج وأمكن تلافي 157 حدثاً قلبياً وعائياً لكل 100 ألف شخص سنوياً، بالمقارنة مع 5% من البالغين و 92 حدثاً بالتدبير العلاجي للاختطار القلبي الوعائي الإجمالي. إن التدبير العلاجي المستند على الاختطار القلبي الوعائي المرتفع يحسّن على نحو مثالي التوازن بين عدد المحتاجين إلى العلاج وعدد الأحداث القلبية الوعائية التي يمكن تلافيها.

الاستنتاج

إن التدبير العلاجي للاختطار القلبي الوعائي الإجمالي أكثر مردوداً لقاء التكلفة بدرجة كبيرة من التدبير العلاجي لعامل الاختطار الفردي. وتتسق هذه النتائج لدى جميع البلدان، ولاسيما البلدان التي تتشابه اقتصادياً وديموغرافيا من دولة سيشيل.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer la prévalence des facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire (CV) aux Seychelles, un pays africain à revenu moyen, et comparer le rapport coût/efficacité de la prise en charge du facteur de risque principal (traiter les individus présentant une tension artérielle ≥ 140/90 mmHg et/ou une cholestérolémie sérique totale ≥ 6,2 mmol/l) avec celui de la prise en charge fondée sur le risque cardiovasculaire total (traiter les individus présentant un risque cardiovasculaire total ≥ 10% ou ≥ 20%).

Méthodes

La prévalence des facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire et un tableau de prédiction des risques cardiovasculaires pour l'Afrique ont été utilisés pour estimer le risque de survenue d’un événement CV mortel ou non mortel sur une période de 10 ans chez des individus âgés de 40 à 64 ans. Ces chiffres ont servi à comparer la prise en charge du facteur de risque principal et celle du facteur de risque total en termes du nombre de personnes nécessitant un traitement afin de prévenir un événement CV et du nombre d'événements potentiellement évités sur une période de 10 ans. Le traitement chez des patients présentant un risque CV total élevé (≥ 20%) était supposé consister en une combinaison des doses prédéterminées de plusieurs médicaments (polypill). Les analyses de coût se sont limitées aux médicaments.

Résultats

Un risque CV total ≥ 10% et ≥ 20% a été constaté chez 10,8% et 5,1% des individus, respectivement. Avec une prise en charge du facteur de risque principal, il faudrait traiter 60% des adultes, et 157 événements cardiovasculaires sur une population de 100 000 personnes seraient évités chaque année, par rapport à 5% des adultes et 92 événements pour la prise en charge du facteur de risque CV total. Une prise en charge fondée sur un risque CV total élevé optimise l’équilibre entre le nombre de personnes nécessitant un traitement et le nombre d'événements cardiovasculaires évités.

Conclusion

La prise en charge du facteur de risque CV total a un bien meilleur rapport coût/efficacité que la prise en charge du facteur de risque principal. Ces résultats sont pertinents pour tous les pays, mais plus particulièrement pour ceux présentant des caractéristiques économiques et démographiques similaires à celles des Seychelles.

Resumen

Objetivo

Evaluar la prevalencia de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular (CV) en las Seychelles, un país africano de ingresos medios, y comparar la rentabilidad de la gestión basada en un solo factor de riesgo (tratamiento de personas con una tensión arterial superior o igual a 140/90 mm Hg y/o una concentración sérica de colesterol superior o igual a 6,2 mmol/l) con la gestión del riesgo CV total (tratamiento de personas con un riesgo CV total mayor o igual al 10% o mayor o igual al 20%).

Métodos

Para calcular el riesgo de padecer un episodio CV mortal o no mortal de las personas de entre 40 y 64 años a lo largo de un periodo de 10 años, se emplearon la prevalencia del factor de riesgo CV y una gráfica de predicción del riesgo CV en África. Estas cifras se emplearon para comparar la gestión del riesgo individual con la gestión del riesgo total, en cuanto al número de personas que necesitarían tratamiento para evitar un episodio CV y el número de episodios que podrían evitarse durante un periodo de 10 años. Se presupuso que el tratamiento de los pacientes con un riesgo CV total (≥ 20%) consistía en una asociación de varios fármacos en dosis fijas (policomprimido). Los análisis de costes se limitaron a la medicación.

Resultados

Se observó un riesgo CV total ≥ al 10% y ≥ al 20% en el 10,8% y el 5,1% de los individuos, respectivamente. En el caso de la gestión del riesgo individual, el 60% de los adultos necesitarían recibir tratamiento y se evitarían anualmente 157 episodios cardiovasculares por cada 100 000 personas, en contraposición al 5% de los adultos y los 92 episodios que se evitarían con una gestión del riesgo CV total. El tratamiento en función del riesgo CV total elevado optimiza el equilibrio entre el número de personas que necesitarían tratamiento y el número de episodios CV que se podrían evitar.

Conclusión

La gestión del riesgo CV total es mucho más rentable que la individual basada en un solo factor de riesgo. Estos resultados son aplicables a todos los países, en especial a aquellos que sean económica y demográficamente similares a las Seychelles.

Резюме

Цель

Оценить распространенность факторов риска развития сердечно-сосудистых заболеваний (ССЗ) в Республике Сейшельские Острова, африканской стране со средним доходом, и сравнить соотношение «затраты – эффективность» при управлении отдельно взятым риск-фактором (лечение больных с артериальным кровяным давлением от 140/90 мм рт. ст. и/или содержанием общего холестерина в сыворотке крови от 6,2 ммоль/л) и при управлении суммарным риском развития ССЗ ≥ 10% или ≥ 20%).

Методы

Для оценки 10-летнего риска летального или не летального сердечно-сосудистого приступа у лиц в возрасте 40–64 лет использовались показатель распространенности факторов риска ССЗ и номограмма риска ССЗ для Африки. Эти цифры использовались для сравнения управления отдельно взятым риск-фактором и управления суммарным риском ССЗ в отношении численности лиц, нуждающихся в лечении для предотвращения приступа ССЗ, и количества приступов ССЗ, потенциально предотвращенных в течение 10 лет. Предполагалось, что лечение больных с высоким суммарным риском развития ССЗ (≥ 20%) состояло в приеме комбинированных лекарственных препаратов с фиксированными дозами (polypill). Анализ затрат ограничивался ценой лекарственного средства.

Результаты

Суммарный риск развитияl ССЗ на уровне ≥ 10% и ≥ 20% был выявлен у 10,8% and 5,1% лиц, соответственно. При управлении отдельно взятым риск-фактором нуждались бы в лечении 60% взрослых, и были бы предотвращены 157 приступов ССЗ на 100 тысяч человек населения в год (при управлении суммарным риском ССЗ – 5% взрослых и 92 приступа, соответственно). Управление на основе высокого суммарного риска развития ССЗ ведет к оптимизации баланса между численностью лиц, нуждающихся в лечении, и количеством предотвращенных приступов ССЗ.

Вывод

Управление суммарным риском развития ССЗ более рентабельно, чем управление отдельно взятым риск-фактором. Эти результаты применимы ко всем странам, но особенно к тем, которые в экономическом и демографическом отношениях аналогичны Сейшелам.

摘要

目的

旨在评估中等收入非洲国家塞舌尔的心血管风险因素情况,并比较单一危险因素管理(治疗动脉血压≥ 140/90 mmHg和/或血清总胆固醇≥ 6.2 mmol/l的个人)的成本效益和综合危险因素管理(对综合危险因素≥ 10%或≥ 20%个体治疗)的成本效益。

方法

用非洲心血管危险因素情况和心血管危险预测图来估测40-64岁个人遭受致命的或非致命的心血管事件的十年风险率。这些数据用来比较单一危险因素管理与综合危险因素管理在评价需要治疗以避免心血管事件的人数和十年间潜在的避免心血管事件的数量方面的差异。假定对心血管综合危险因素高的病人治疗由几种药物(复方制剂)的固定剂量组合构成。成本分析则仅限于药物治疗。

结果

我们发现综合心血管危险比率≥ 10%和≥ 20%的个人分别为10.8%和5.1%。如运用单一危险因素管理,则60%的成年人需要进行治疗,每年每10万人中将避免157例心血管事件;而如运用心血管综合危险因素管理,则仅有5%的成年人需要进行治疗且每年每10万人中将避免92例心血管事件。基于高心血管综合危险因素的管理优化了需要治疗人数和避免的心血管事件数量之间的平衡。

结论

综合心血管危险因素管理比单一危险因素管理更具成本效益。这些发现适用于所有国家,特别是那些在经济上和人口统计上类似于塞舌尔的国家。

Introduction

Every year approximately 17 million people die from cardiovascular (CV) disease. Of the deaths attributable to CV disease, which comprise roughly 29% of all deaths, about 80% occur in low- and middle-income countries, often in people less than 60 years of age.1 However, morbidity and mortality from CV disease could be greatly reduced through interventions that target its risk factors. Thanks to population-wide policies and individual risk management,2 in the past 30 years CV disease has decreased by more than 50% in many developed countries.3

At the individual level, prevention centres mainly on identifying and treating individuals with increased CV risk to prevent heart attacks and stroke. Traditionally, treatment has targeted individuals with one or more risk factors, such as high arterial blood pressure or high serum cholesterol.4 Reducing blood pressure and serum cholesterol can, indeed, effectively prevent or delay CV events.5 However, single-risk-factor approaches are only partially effective because individuals with both mildly elevated blood pressure and mildly elevated serum cholesterol, or those with high levels of one but not the other, may be at low total risk of CV disease.

Total CV risk factor management has been advocated for several years as an alternative approach.6,7 It posits that the higher an individual’s total CV risk before treatment is initiated, the greater the cost-effectiveness of treatment.5,6 Under this approach, individuals are managed in accordance with their baseline CV risk. This strategy is in principle more effective and less costly than the single-risk-factor approach because treatment is limited to individuals with a high total CV risk.5,7,8

The total risk approach relies on prediction scores. These have been developed and validated primarily in high-income countries9,10 and subsequently adapted to other populations after re-calibration.11,12 The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) recently developed a set of CV risk prediction charts for use in all regions of the world.7,13

While treatment relying on separate medications to control individual risk factors such as high serum cholesterol and high blood pressure remains a valid option, individuals with high CV risk could perhaps be managed in a more cost-effective way with a fixed-dose combination drug (polypill) targeting multiple risk factors simultaneously.14,15 A polypill has several potential advantages: (i) avoiding complex treatment algorithms; (ii) avoiding multiple dose titration steps; (iii) improving treatment adherence; and (iv) reducing costs.15 Yusuf has suggested that a combination of four drugs (aspirin, a β-blocker, a statin and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor) could reduce the incidence of CV events by 75% in patients with vascular disease.16 Wald & Law have shown that administering a polypill containing three antihypertensives, a statin, aspirin and folic acid to all individuals who either have CV disease or are older than 55 years would safely reduce ischaemic heart disease and stroke by more than 80%.17 While this promising approach has generated considerable debate,15 a first trial has now been successfully completed in India18 and at least seven other trials are being conducted in both developing and developed countries.15

The present study has two objectives: (i) to assess the distribution of CV risk in Seychelles based on the actual distribution of CV risk factors in the population and on data derived from WHO/ISH risk prediction charts, and (ii) to compare two distinct risk management strategies – single-risk-factor management and total risk management – in terms of the number of people one would need to treat and the number of CV events that would be averted with each over a span of 10 years.

Methods

Seychelles is a small and rapidly developing middle-income island state located east of Kenya in Africa. The country has 86 000 inhabitants, primarily of African descent. Nearly 40% of all deaths are attributable to CV disease.19 The per capita gross domestic product (GDP) rose, in real terms, from 2927 United States dollars (US$) in 1980 to US$ 5239 in 2004, largely owing to booming tourism, industrial fishing and services. Health care is available free of cost to all inhabitants through a national health system.

A population-based examination survey of CV risk factors was conducted in 2004 under the auspices of the Ministry of Health following technical and ethical reviews, and its methods and results have been published.20–22 Briefly, a random sex- and age-stratified sample of the population aged 25–64 years was drawn from an electronic database of the entire population. Eligible individuals were free to participate in the survey and gave written informed consent.

A health behaviour questionnaire was administered to the participants. Blood pressure was measured three times every 2 minutes after the participants had been quiet in the study centre for at least 30 minutes. The last two readings were used for the analysis. Arterial blood pressure was defined as high if ≥ 140/90 mmHg. Total serum cholesterol, measured from frozen serum with a Hitachi 917 instrument and Roche reagents, was defined as high if ≥ 6.2 mmol/l. Fasting plasma glucose was measured with a Cholestec LDX system, and individuals were classified as diabetic if their blood glucose level was ≥ 7.0 mmol/l or if they reported being on treatment for diabetes.22 Individuals who reported smoking at least one cigarette per day were classified as current tobacco users.

Using the WHO/ISH risk prediction charts for the African D subregion, which comprises African countries with relatively higher income and lower mortality, we calculated each participant’s predicted total CV risk (defined as the risk of suffering a fatal or non-fatal CV event, namely acute myocardial infarction or stroke, over the next 10 years).7,13 All results in this study are only for participants aged 40 years or older, since the WHO/ISH risk score is designed for this age group. We did not consider treatment being received for high arterial blood pressure or high serum cholesterol because these variables are not factored into the risk score. To use the WHO/ISH risk charts to determine CV risk, information on sex, age, systolic blood pressure, total serum cholesterol, smoking status (yes/no) and diabetes status (yes/no) is needed. These charts categorize CV risk as follows: 0–9% (low); 10–19% (intermediate); 20–29%, 30–39% and ≥ 40% (high). When allocating a specific risk to individuals, we used the middle values of these ranges (e.g. 15% for the 10–19% CV risk category) and, for the group with a risk ≥ 40%, we assumed that everyone had a risk of 50%.

We estimated the reduction in CV risk associated with treating people with hypertension and/or high serum cholesterol versus administering the polypill to individuals with high CV risk.23–25 We assumed that the polypill was equal in composition to the low-dose polycap being used in the only polypill trial published to date: simvastatin, 20 mg; three antihypertensives at half the recommended dose; and aspirin, 100 mg.15,18 This fixed-dose combination drug would reduce the risk of ischaemic heart disease and stroke by 62% and 48%, respectively.15 Risk reduction estimates for high-income countries often assume a ratio of coronary events to stroke of 3:1,10,25 but this ratio is generally different in countries undergoing the epidemiological transition. For this study we assumed a ratio of coronary events to stroke of 1:2 to reflect the fact that in Seychelles hospitals receive more cases of stroke than of coronary heart disease and that mortality from stroke is twice as high as from coronary heart disease.26 Table 1 summarizes the effect estimates considered in this paper.

Table 1. Relative risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular (CV) events associated with the use of selected CV risk management strategies, Seychelles.

| Management strategy and medication | RRa |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | CEb | CV eventc | |

| Single-risk-factor | |||

| Serum cholesterol ≥ 6.2 mmol/l | |||

| Statin | 0.92 | 0.73 | 0.86 |

| Blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg | |||

| Three classes of drugs | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.70 |

| Total CV risk | 0.84 | 0.68 | 0.79 |

| Aspirin | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.47 |

| Polypilld | |||

CE, coronary event; RR, relative risk.

a See text for explanations and references underlying the RR estimates provided in this table. The RR of experiencing a CV event was calculated from the risk factor reductions obtained with the low-dose polycap. An incidence ratio of stroke to coronary events of 2:1 was assumed.18

b Includes unstable angina and myocardial infarction.

c Includes both stroke and coronary events.

d Composed of aspirin, a statin, a diuretic and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

We limited our cost analyses to medication prices and adopted the perspective of the health-care provider (i.e. costs incurred to the Ministry of Health), since in Seychelles medical care is provided mostly through a national health system. We used actual drug procurement prices provided by the Ministry of Health20 and the prices of generic drugs and of the polypill published in the literature27 (Table 2). Consistent with clinical guidelines and with the actual prevalence of different levels of hypertension in the population,4,20 we assumed that treatment for hypertension consisted of a single drug in 20% of cases, two drugs in 60%, three drugs in 15% and four drugs in 5%. We assumed that a diuretic was included in 80% of all single-dose regimens and in all combination regimens for hypertension.

Table 2. Cost of cardiovascular (CV) medications used for selected CV risk management strategies, Seychelles, 2004.

| Management strategy and medication | Cost (2004 US$) per daya |

|

|---|---|---|

| Seychelles | India | |

| Single-risk-factor | ||

| BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg | ||

| Lisinopril (ACEI) | 0.38 | 0.15 |

| Atenolol (BB) | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Hydrochlorothiazide (D) | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Amlodipine (CCB) | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| TSC ≥ 6.2 mmol/l | ||

| Atorvastatin | 1.46 | 0.12 |

| BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg or TSC ≥ 6.2 mmol/l | ||

| Antihypertensives and atorvastatin | 1.16 | 0.18 |

| Total CV risk | ||

| CV risk ≥ 10% | ||

| Polypillb | – | 0.26 |

| CV risk ≥ 20% | ||

| Polypillb | – | 0.26 |

| CV risk ≥ 20% or BP ≥ 160/100 mmHg or SC ≥ 8.0 mmol/l | ||

| Polypillb | – | 0.26 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; BB, β-blocker; BP, blood pressure; CCB, calcium channel blocker; D, diuretic; TSC, total serum cholesterol; US$, United States dollars.

a The costs of medications in India and Seychelles were obtained from references Gupta et al.27 and Bovet et al.,20 respectively.

b Composed of aspirin, a statin, a diuretic and an ACEI.

Risk factor prevalence (and 95% confidence intervals, CIs) and total CV risk were tabulated by age and sex. Overall estimates were weighted to the distribution of the WHO standard population.28 Analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel (Redmond, United States of America) and Stata version IC 11 (StataCorp. LP, College Station, USA).

Results

The distribution of the CV risk factors used to calculate the CV risk prediction score for people aged 40–64 years is shown in Table 3. The prevalence of high blood pressure was 45% and the prevalence of high total serum cholesterol was 25% in men and 32% in women. Either condition or both existed in 63% of men and 57% of women.29 Diabetes prevalence was similar in men and women (16% and 15%, respectively). Smoking was more prevalent among men (31%) than among women (4%).

Table 3. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in people aged 40–64 years, Seychelles, 2004.

| Risk factor | % (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 374) | Women (n = 442) | All (n = 816) | |

| Hypertension | |||

| BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg | 50.0 (44.9–55.1) | 40.0 (35.4–44.5) | 45.0 (41.6–48.5) |

| BP ≥ 160/100 mmHg | 19.6 (15.5–23.6) | 14.2 (11.0–17.5) | 16.9 (14.4–19.5) |

| Hypercholsterolaemia | |||

| TSC ≥ 6.2 mmol/l | 24.6 (20.2–29.0) | 31.6 (27.3–36.0) | 28.1 (25.0–31.2) |

| TSC ≥ 8.0 mmol/l | 2.8 (1.1–4.5) | 5.6 (3.5–7.8) | 4.2 (2.8–5.6) |

| Hypertension or hypercholsterolaemia | |||

| BP ≥ 140/90 or TSC ≥ 6.2 | 62.8 (57.8–67.7) | 56.6 (52.0–61.3) | 59.7 (56.3–63.1) |

| BP ≥ 160/100 or TSC ≥ 8.0 | 21.6 (17.4–25.8) | 19.1 (15.4–22.8) | 20.4 (17.6–23.1) |

| Diabetes (FBG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l) | 15.8 (12.1–19.5) | 15.3 (12.0–18.7) | 15.6 (13.1–18.1) |

| Smoking (≥ 1 cigarette daily) | 31.1 (26.4–35.8) | 4.0 (2.1–5.8) | 17.7 (15.0–20.3) |

BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; FBG, fasting blood glucose; TSC: total serum cholesterol.

Table 4 shows the distribution of total CV risk (i.e. the risk of suffering a fatal or non-fatal CV event over the ensuing 10 years) in men and women aged 40–64 years. Overall, 89% of individuals in this age group had a low CV risk (0–9.9%), 6% had an intermediate risk (≥ 10% but < 20%) and 5% had a high risk (≥ 20%). The percentage of men and women at low risk was similar, but a greater percentage of men than women were at high risk. As expected, people aged 55–64 years had an intermediate or high CV risk much more often than people aged 40–54 years (25% versus 5%, respectively).

Table 4. Percentagea of people aged 40–64 years in various total cardiovascular risk categories, Seychelles, 2004.

| Total risk (%) | % (95% CI) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men |

Women |

Total |

|||||||||

| 40–54 years (n = 223) | 55–64 years (n = 144) | 40–64 years (n = 367) | 40–54 years (n = 260) | 55–64 years (n = 178) | 40–64 years (n = 438) | 40–54 years (n = 483) | 55–64 years (n = 322) | 40–64 years (n = 805) | |||

| 0–9.9 | 95.1 (91.4–97.2) | 75.0 (67.3–81.4) | 89.0 (85.5–91.6) | 96.1 (93.0–97.8) | 74.7 (67.8–80.6) | 89.4 (86.4–91.8) | 95.5 (93.4–97.0) | 74.9 (69.8–79.3) | 89.2 (87.0–91.0) | ||

| 10–19.9 | 2.4 (1.1–5.2) | 13.2 (8.6–19.8) | 5.7 (3.8–8.3) | 2.5 (1.2–5.2) | 12.9 (8.7–18.7) | 5.8 (4.0–8.2) | 2.5 (1.4–4.2) | 13.1 (9.8–17.3) | 5.7 (4.4–7.4) | ||

| 20–29.9 | 0.4 (0.06–2.8) | 2.8 (1.0–7.2) | 1.1 (0.5–2.7) | 1.4 (0.5–3.8) | 10.1 (6.5–15.5) | 4.2 (2.7–6.3) | 0.9 (0.4–2.2) | 6.5 (4.3–9.7) | 2.6 (1.8–3.8) | ||

| 30–39.9 | 0.8 (0.2–3.1) | 4.9 (2.3–9.9) | 2.0 (1.1–3.9) | 0.0 | 0.6 (0.08–3.9) | 0.2 (0.03–1.2) | 0.4 (0.1–1.6) | 2.7 (1.4–5.3) | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | ||

| ≥ 40 | 1.4 (0.4–4.2) | 4.2 (1.9–9.0) | 2.2 (1.1–4.3) | 0.0 | 1.7 (0.5–5.1) | 0.5 (0.2–1.6) | 0.7 (0.2–2.2) | 2.9 (1.5–5.5) | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) | ||

CI, confidence interval.

a Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding and missing data.

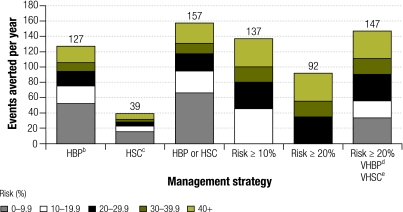

Fig. 1 displays the number of CV events that would be averted annually (per 100 000 individuals aged 40–64 years) with different management strategies. With the three single-risk-factor approaches shown (i.e. treating all individuals with only high blood pressure, only elevated serum cholesterol or both conditions), the number of CV events averted would be 127, 39 and 157, respectively. With the total CV risk approach, the number of CV events averted would be 137 for a CV risk of ≥ 10% and 92 for a CV risk of ≥ 20%, respectively. With the mixed management strategy suggested in the WHO guidelines13 (i.e. treating all individuals with a total CV risk ≥ 20% and all individuals with markedly elevated blood pressure [≥ 160/100 mmHg] or markedly elevated serum cholesterol [≥ 8.0 mmol/l]), 147 CV events would be averted. Fig. 1 also shows that the number of CV events averted with single-risk-factor approaches was substantial among the category having a low CV risk.

Fig. 1.

Number of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular (CV) eventsa averted annually per 100 000 people aged 40–64 years through different CV risk management strategies, by categories of total CV risk, Seychelles, 2004

a The expected annual number of fatal and non-fatal CV events in the untreated population of Seychelles aged 40–64 is 705 per 100 000 people.

b High blood pressure, defined as BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg.

c High serum cholesterol, defined as total serum cholesterol ≥ 6.2 mmol/l.

d Very high blood pressure, defined as BP ≥ 160/100 mmHg.

e Very high serum cholesterol, defined as total serum cholesterol ≥ 8.0 mmol/l.

Table 5 shows the number of CV events averted every year (per 100 000 persons aged 40–64 years), by sex and age group, with each management strategy. Fewer CV events would be averted among individuals aged 40–54 years than among individuals aged 55–64 years, and fewer would be averted in women than in men.

Table 5. Fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events averted in people aged 40–64 years through different cardiovascular (CV) risk management strategies, by sex and age, Seychelles, 2004.

| Management strategy and medication | Events averteda |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40–54 years |

55–64 years |

||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| Single-risk-factor | |||||

| BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg | 35 | 24 | 39 | 29 | |

| TSC ≥ 6.2 mmol/l | 11 | 8 | 8 | 12 | |

| BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg or TSC ≥ 6.2 mmol/l | 44 | 30 | 44 | 39 | |

| Total CV risk | |||||

| CV risk ≥ 10% | 26 | 13 | 52 | 45 | |

| CV risk ≥ 20% | 20 | 6 | 36 | 29 | |

| CV risk ≥ 20% or BP ≥ 160/100 mmHg or TSC ≥ 8.0 mmol/l | 37 | 23 | 46 | 42 | |

BP, blood pressure; TSC, total serum cholesterol.

a Annually per 100 000 people aged 40–64 years.

Table 6 compares the management strategies examined in terms of the total number of persons one would have to treat, overall medication costs (using two different sets of prices) and the number of CV events averted. The figures given are per year and per 100 000 persons aged 40–64 years and 100% adherence to treatment is assumed. The number of persons that one would need to treat ranged from 5114 for the strategy based on treating only individuals with a high total CV risk, to 59 741 for the strategy based on treating all individuals with hypertension and/or elevated serum cholesterol. Total drug costs varied almost 10-fold between the different management strategies, from US$ 0.49 to 3.89 million (based on drug prices in India in 2005). In 2004, about 37% and 1% of adults aged 40–64 years, respectively, are being treated for hypertension and high serum cholesterol in Seychelles. If adherence to medications were 100% (as we have assumed for the other strategies), 37 667 persons would need to be treated to avert 103 CV events. This represents an annual cost of 2.45 US$ million per 100 000 adults aged 40–64 years. To prevent a single CV event, 366 people would need to be treated.

Table 6. Cost-effectivenessa of various cardiovascular (CV) risk management strategies in people aged 40–64 years, Seychelles, 2004.

| Management strategy | People to treatb | CV events avertedb | NNTc | Medication cost |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seychelles (2004 US$) |

India (2005 US$) |

|||||||

| Annually (millions) | Per CV event averted | Annually (millions) | Per CV event averted | |||||

| Single-risk-factor | ||||||||

| BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg | 44 899 | 127 | 354 | 3.25 | 25 679 | 1.84 | 14 534 | |

| TSC ≥ 6.2 mmol/l | 28 317 | 39 | 727 | 15.09 | 387 275 | 1.24 | 31 831 | |

| BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg or TSC ≥ 6.2 mmol/l | 59 741 | 157 | 379 | 25.27 | 160 452 | 3.89 | 24 678 | |

| Total CV risk | ||||||||

| CV risk ≥ 10% | 10 837 | 137 | 79 | NAd | NA | 1.03 | 7 499 | |

| CV risk ≥ 20% | 5 114 | 92 | 56 | NA | NA | 0.49 | 5 291 | |

| CV risk ≥ 20% or BP ≥ 160/100 mmHg or TSC ≥ 8.0 mmol/l | 20 653 | 147 | 140 | NA | NA | 1.96 | 13 307 | |

| Current situation | 37 667 | 103 | 366 | 15.93 | 154 674 | 2.45 | 23 789 | |

BP, blood pressure; NNT, number needed to treat; TSC, total serum cholesterol; US$, United States dollars.

a All cost and cost-effectiveness estimates are based on the prices of medications only and on the assumptions that all persons in the population who have a specified condition are known and that adherence to treatment is 100%.

b Annually per 100 000 people aged 40–64 years. For “people to treat” the figures correspond to the prevalences of the specified conditions per 100 000 people.

c Number of persons aged 40–64 years that one would need to treat annually (per 100 000) to avoid one fatal or non-fatal CV event.

d Not applicable since the polypill is not yet available in Seychelles.

One could also increment the number of CV events averted while reducing the number of people one would need to treat by adopting a management strategy based on treating all people with a total CV risk of ≥ 10% (137 events would be averted for every 10 837 individuals treated; 79 people would have to be treated to prevent one CV event). With WHO’s mixed strategy, described above, 147 events would be averted for every 20 653 individuals treated. Expectedly, the number of persons one would need to treat to avert one CV event would be lowest with the strategy based on treating only those with a high total CV risk (around 56:1) and highest with single-risk-factor approaches (around 400:1).

Discussion

This study is one of the first to investigate the distribution of total CV risk in an African country and the population impact of various management strategies. We found that around 10% of the population aged 40–64 years was at moderate or high CV risk. We also showed that far fewer individuals would need to be treated if total CV risk management rather than single-risk-factor management were adopted, while the number of CV events averted by these strategies would not differ much. Because we relied on several assumptions, our findings apply to Seychelles and potentially to other middle-income African countries, but to identify optimal management strategies for the prevention of CV in low-resource settings more research is required.

The prevalence of elevated CV risk in the population of Seychelles resembles the prevalence found in other populations. For example, 16% of males and 2% of all individuals aged 45 years or older in the United States had a Framingham coronary risk score ≥ 20%.30 In Spain, 7.3% of adults aged 40–75 years had a 10-year risk of suffering a fatal CV event ≥ 10% according to the European SCORE.11 In China, 11.3% of men aged 18–74 years had a 10-year risk of suffering a fatal or non-fatal CV event ≥ 10% according to a calibrated version of the European Score.12 Since no cohort studies exist, WHO/ISH prediction charts for CV risk have not yet been validated and calibrated in Africa. However, they are in all likelihood appropriate for ranking individuals according to their CV risk (i.e. for distinguishing those at increased risk from those at low risk) and a valuable tool for the management of CV in middle-income African countries.

On the basis of medication costs exclusively, a management strategy based on total CV risk is more cost-effective and much less expensive for health-care providers than single-risk-factor approaches. This finding is consistent with current evidence from developed5,6,17,25 and developing countries.31 Our results highlight the critical need for low-cost generic medications. It should be noted that we underestimated costs, since we did not factor in non-medication costs (e.g. blood tests, medical visits, relevant training of health professionals, health-care infrastructures, etc). However, the proportionate differences in cost-effectiveness between management strategies are probably fairly insensitive to both medication and non-medication costs since these would apply equally across management strategies. However, a further argument highlighting the cost-effectiveness of total CV risk strategies is that single-risk-factor management approaches where high coverage is needed would require a major upscaling of both the health-care infrastructures and other resources related to case management, since more patients would have to be treated than with a total CV risk approach.

Management strategies based on total CV risk improve both cost-effectiveness and affordability by optimizing the ratio between the number of persons treated and the number of CV events averted. WHO also proposes a mixed approach that involves treating all individuals with high CV risk as well as individuals with very high blood pressure or serum cholesterol.13 This may appeal to clinicians who are reluctant to abstain from prescribing drugs to people with hypertension or hypercholesterolaemia even when their total CV risk is low. However, it is much less efficient than the strategy based on high total CV risk alone. Hence, governments may wish to educate physicians and the public about the advantages of an absolute risk approach.

In middle-income countries, which can allocate more resources to health care than low-income countries, a strategy based on treating people with a total CV risk > 10% may be more cost-effective than a strategy based on treating people whose total CV risk is > 20%. Seychelles invests about US$ 564 per capita yearly in health care.32 Thus, it invests 10 times more than some low-income countries but 10 times less than some industrialized countries. In this context, a management strategy targeting people with a high total CV risk may optimize the balance between the number of persons that need to be treated and the number of CV events averted, but if there is willingness to pay, treating people with a lower CV risk may be feasible. A limiting factor, however, is that the WHO/ISH risk prediction chart does not stratify risks < 10%.

Management strategies based on total CV risk are not without disadvantages, including poor acceptability by health professionals and patients, although recent studies suggest that the polypill could gain acceptance among physicians.33,34 Based on its cost-effectiveness, WHO has defined the total CV risk approach as essential for the primary prevention of heart attacks and strokes.35 This highlights the need to provide information about it to both health professionals and patients36 and underscores the main message of this study: that a management strategy based on high total CV risk is more cost-effective than single-risk-factor approaches, irrespective of whether patients are prescribed a polypill or separate medications.

There is limited evidence that aspirin is effective for the primary prevention of CV disease. Therefore, some challenge the idea of including it in the polypill, particularly in countries where haemorrhagic stroke is common. However, the polypill used in seven ongoing trials has contained aspirin.15 Furthermore, our main finding is altered little when the analysis is performed with a polypill without aspirin. The number of CV events averted by the polypill with and without aspirin would be 137 and 105, respectively, if those with a total CV risk ≥ 10% were treated (data not shown).

We did not include treatment for diabetes in this study since guidelines recommend glucose-lowering medication for all affected individuals, irrespective of their actual CV risk. Furthermore, diabetes treatment improves non-CV as well as CV outcomes.37 We did not consider smoking cessation either, since smoking cessation therapy (behavioural and/or pharmacological) should be offered to all smokers, irrespective of their CV risk, and since quitting the habit also improves non-CV outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, WHO/ISH CV risk prediction charts have not been validated in the African continent, as stated earlier, for lack of cohort studies in the region. While the relative risk of CV events associated with the risk factors included in the WHO/ISH charts is similar in all regions of the world,38,39 the underlying overall risk of CV disease may differ markedly between countries in the same region and the charts may need to be further validated for routine use in clinical practice. Second, the charts do not factor in any treatment being received to control CV risk factors, so we omitted this information from our study. This is not likely to have affected the findings, however, since more than half of hypertensive individuals in Seychelles go untreated21 and, according to a previous study, fewer than 30% of those who are treated take their medications regularly after 12 months of follow-up.40 As more and more people in low- and middle-income countries get treated for hypertension or diabetes, this information may need to be factored into future versions of the WHO/ISH charts. Third, WHO/ISH risk prediction charts only indicate a risk range, and we applied the mid-range scores to individuals. Future versions of the charts could incorporate finer CV risk stratification, especially for risks < 10%. Fourth, we used relative risk reduction estimates from studies performed outside Africa in the absence of African trials, but since the relative risk of CV events associated with the risk factors considered in the WHO/ISH charts was shown to be similar across regions,39 this seems admissible. Fifth, we did not consider competing causes of morbidity and mortality when we estimated the number of CV events averted annually, nor did we consider any discount rate when we calculated the costs of averting CV events. Factoring in these variables would alter the number of events averted but not our main message, namely, that a total risk approach is more cost-effective than single-risk approaches. Sixth, we did not conduct sensitivity analyses for different levels of treatment adherences and assumed 100% adherence to estimate the greatest possible impact. However, lower adherence rates would probably apply similarly across all the management strategies considered. Seventh, we lacked information on past CV events (myocardial infarction, stroke), whose presence would automatically place an individual in the high-risk category. However, most of these individuals were probably already categorized as high-risk based on the WHO/ISH risk prediction score. Eighth, it would have been preferable to estimate the cost per life year gained or per quality-adjusted life year gained of every CV event averted rather than the sole cost of the medications needed to avert CV events. However, calculating the life years gained would require further data and making assumptions about the case fatality rates for acute myocardial infarction and stroke in this population. Ninth, some believe that CV risk prediction scores should factor in the occurrence of CV events over longer periods, perhaps 30 years instead of 10.41 Furthermore, the indications for the use of a polypill are still being debated,15,42,43 but evidence on the polypill’s applicability and effectiveness is emerging.15,18 Finally, with a fairly high GDP per capita and a small population, Seychelles is hardly representative of the majority of African countries. Thus, the feasibility of scaling up health services to implement new management guidelines based on total CV risk and deploying new treatment strategies (e.g. adding the polypill to the list of essential medicines) requires country-specific studies.

A strength of this study is its reliance on a population survey with a high participation rate to measure the risk factors used in calculating the CV risk prediction score. Our data also provide the first estimates of CV risk in the African region and should trigger further studies on these important issues.

In conclusion, around 10% of the population of Seychelles aged 40–65 years has a moderate or high total risk of CV, and management strategies targeting individuals with a high total CV risk would call for treating fewer people than would single-risk-factor approaches while averting approximately the same number of CV events. They would save costs without sacrificing health benefits and are conceivably of special interest to countries with resource constraints. However, any case management strategy, regardless of how cost-effective it may be, will involve high total costs given that so many people have to be treated on a daily basis for years. Furthermore, some case management strategies can widen health inequalities by attracting people with better education and income.36 This underlines the critical importance of public health interventions aimed at preventing CV disease by reducing CV risk factor prevalence in the population.44–46

Acknowledgements

The authors thank D Chisholm, V Lafortune, A Louazani, G Madeleine, P Marques-Vidal, Walter Riesen, B Sambo, B Viswanathan and J William-Fostel for their collaboration. They are also grateful to the Ministry of Health of Seychelles for its continued support of epidemiological research. Roger Ndindjock, the leading author is also affiliated with the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine of the University of Lausanne and University Hospital Centre in Lausanne, Switzerland. Pascal Bovet, a co-author, is also a consultant with the Ministry of Health of Seychelles.

Funding:

The Seychelles Heart Study III received support from the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Seychelles in Victoria under a cooperation agreement with the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine in Lausanne, Switzerland; the Canton Laboratory of Haematology and Clinical Chemistry in St Gallen, Switzerland and WHO/AFRO in Brazzaville, the Congo.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Preventing chronic diseases. A vital investment: WHO global report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capewell S, O’Flaherty M. What explains declining coronary mortality? Lessons and warnings. Heart. 2008;94:1105–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.149930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kesteloot H, Sans S, Kromhout D. Dynamics of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in Western and Eastern Europe between 1970 and 2000. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:107–13. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitworth JA, World Health Organization, International Society of Hypertension Writing Group 2003 World Health Organization (WHO)/International Society of Hypertension (ISH) statement on management of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1983–92. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray CJ, Lauer JA, Hutubessy RC, Niessen L, Tomijima N, Rodgers A, et al. Effectiveness and costs of interventions to lower systolic blood pressure and cholesterol: a global and regional analysis on reduction of cardiovascular-disease risk. Lancet. 2003;361:717–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson R. Updated New Zealand cardiovascular disease risk-benefit prediction guide. BMJ. 2000;320:709–10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7236.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendis S, Lindholm LH, Mancia G, Whitworth J, Alderman M, Lim S, et al. World Health Organization (WHO) and International Society of Hypertension (ISH) risk prediction charts: assessment of cardiovascular risk for prevention and control of cardiovascular disease in low and middle-income countries. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1578–82. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282861fd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaziano TA, Opie LH, Weinstein MC. Cardiovascular disease prevention with a multidrug regimen in the developing world: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:679–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conroy RM, Pyörälä K, Fitzgerald AP, Sans S, Menotti A, De Backer G, et al. SCORE project group Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sans S, Fitzgerald AP, Royo D, Conroy R, Graham I. Calibración de la tabla SCORE de riesgo cardiovascular para España. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2007;60:476–85. doi: 10.1016/S0300-8932(07)75064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang XF, Attia J, D’Este C, Yu XH, Wu XG. A risk score predicted coronary heart disease and stroke in a Chinese cohort. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:951–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prevention of cardiovascular disease Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available from: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/guidelines/PocketGL.ENGLISH.AFR-D-E.rev1.pdf [accessed 2 February 2011].

- 14.Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lonn E, Bosch J, Teo KK, Pais P, Xavier D, Yusuf S. The polypill in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases: key concepts, current status, challenges, and future directions. Circulation. 2010;122:2078–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.873232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yusuf S. Two decades of progress in preventing vascular disease. Lancet. 2002;360:2–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09358-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wald NJ, Law MR. A strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease by more than 80%. BMJ. 2003;326:1419–23. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yusuf S, Pais P, Afzal R, Xavier D, Teo K, Eikelboom J, et al. The Indian polycap study (TIPS). Effects of a polypill (Polycap) on risk factors in middle-aged individuals without cardiovascular disease (Trends Pharmacol Sci): a phase II, double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1341–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statistical abstracts Victoria: Management & Information Systems Division, Republic of Seychelles; 2005.

- 20.Bovet P, Shamlaye C, Gabriel A, Riesen W, Paccaud F. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in a middle-income country and estimated cost of a treatment strategy. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danon-Hersch N, Chiolero A, Shamlaye C, Paccaud F, Bovet P. Decreasing association between body mass index and blood pressure over time. Epidemiology. 2007;18:493–500. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318063eebf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faeh D, William J, Tappy L, Ravussin E, Bovet P. Prevalence, awareness and control of diabetes in the Seychelles and relationship with excess body weight. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, et al. Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brugts JJ, Yetgin T, Hoeks SE, Gotto AM, Shepherd J, Westendorp RG, et al. The benefits of statins in people without established cardiovascular disease but with cardiovascular risk factors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2009;338(jun30 1):b2376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emberson J, Whincup P, Morris R, Walker M, Ebrahim S. Evaluating the impact of population and high-risk strategies for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:484–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bovet P, Didon J, Junker C, Michel P, Paccaud F. Decreasing stroke and myocardial infarction mortality in a country of the African region. Stroke. 2007;38(Suppl 2):535. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta R, Prakash H, Gupta RR. Economic issues in coronary heart disease prevention in India. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:655–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmad O, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez A, Murray C, Lozano R, Inoue M. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cushman M, McClure LA, Howard VJ, Jenny NS, Lakoski SG, Howard G. Implications of increased C-reactive protein for cardiovascular risk stratification in black and white men and women in the US. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1627–36. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.122093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim SS, Gaziano TA, Gakidou E, Reddy KS, Farzadfar F, Lozano R, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular disease in high-risk individuals in low-income and middle-income countries: health effects and costs. Lancet. 2007;370:2054–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World health statistics Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viera AJ, Sheridan SL, Edwards T, Soliman EZ, Harris R, Furberg CD. Acceptance of a polypill approach to prevent cardiovascular disease among a sample of US. Physicians. 2011;52:10–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huy C, Litaker D. Physician support for a population-based pharmaceutical approach to cardiovascular prevention: not there yet. Prev Med. 2011;52:18–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Package of essential noncommunicable (WHO-PEN) disease interventions for primary health care in low resource settings Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wells S, Whittaker R, Dorey E, Bullen C. Harnessing health IT for improved cardiovascular risk management. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes–2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl 1):S11–61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, Chin SL, Rao-Melacini P, et al. INTERSTROKE investigators Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet. 2010;376:112–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. INTERHEART Study Investigators Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bovet P, Burnier M, Madeleine G, Waeber B, Paccaud F. Monitoring one-year compliance to antihypertension medication in the Seychelles. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:33–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Larson MG, Massaro JM, Vasan RS. Predicting the 30-year risk of cardiovascular disease: the framingham heart study. Circulation. 2009;119:3078–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guglietta A, Guerrero M. Issues to consider in the pharmaceutical development of a cardiovascular polypill. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:112–9. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sleight P, Pouleur H, Zannad F. Benefits, challenges, and registerability of the polypill. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1651–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asaria P, Chisholm D, Mathers C, Ezzati M, Beaglehole R. Chronic disease prevention: health effects and financial costs of strategies to reduce salt intake and control tobacco use. Lancet. 2007;370:2044–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61698-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prevention of cardiovascular disease at population level (NICE Publication 35). London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2010.

- 46.Wright JT, Jr, Dunn JK, Cutler JA, Davis BR, Cushman WC, Ford CE, et al. ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group Outcomes in hypertensive black and nonblack patients treated with chlorthalidone, amlodipine, and lisinopril. JAMA. 2005;293:1595–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]