Abstract

Objective

To present data from a 2008 infant mortality survey conducted in Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank and analyse infant mortality trends among Palestine refugees in 1995–2005.

Methods

Following the preceding birth technique, mothers who were registering a new birth were asked if the preceding child was alive or dead, the day the child was born and the date of birth of the neonate whose birth was being registered. From this information, neonatal, infant and early child mortality rates were estimated. The age at death for early child mortality was determined by the mean interval between successive births and the mean age of neonates at registration.

Findings

In 2005–2006, infant mortality among Palestine refugees ranged from 28 deaths per 100 000 live births in the Syrian Arab Republic to 19 in Lebanon. Thus, infant mortality in Palestine refugees is among the lowest in the Near East. However, infant mortality has stopped decreasing in recent years, although it remains at a level compatible with the attainment of Millennium Development Goal 4.

Conclusion

Largely owing to the primary health care provided by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) for Palestine Refugees in the Near East and other entities, infant mortality among Palestine refugees had consistently decreased. However, it is no longer dropping. Measures to address the most likely reasons – early marriage and childbearing, poor socioeconomic conditions and limited access to good perinatal care – are needed.

Résumé

Objectif

Présenter les données d’une enquête sur la mortalité infantile menée en 2008 en Jordanie, au Liban, en République arabe syrienne, dans la bande de Gaza et en Cisjordanie, et analyser les tendances de la mortalité infantile chez les réfugiés palestiniens entre 1995 et 2005.

Méthodes

Selon la technique de la naissance précédente, il était demandé aux mères déclarant une nouvelle naissance si l’enfant précédent était vivant ou mort, le jour où cet enfant était né et la date de naissance du nouveau-né dont la naissance était enregistrée. À partir de ces informations, on a estimé les taux de mortalité néonatale, infantile et juvénile. En ce qui concerne la mortalité juvénile, l’âge au moment du décès a été déterminé à l’aide de l’intervalle moyen entre les naissances successives et l’âge moyen des nouveau-nés lors de l’enregistrement.

Résultats

Sur la période 2005–2006, la mortalité infantile chez les réfugiés palestiniens allait de 28 décès pour 100 000 naissances vivantes en République arabe syrienne à 19 décès au Liban. Par conséquent, la mortalité infantile chez les réfugiés palestiniens compte parmi les plus basses du Proche-Orient. Toutefois, la mortalité infantile a cessé de diminuer ces dernières années, bien qu’elle demeure à un niveau compatible avec la réalisation de l'objectif 4 du Millénaire pour le développement.

Conclusion

C’est essentiellement grâce aux soins de santé primaire dispensés par l’Office des secours et des travaux des Nations Unies pour les réfugiés de Palestine dans le Proche-Orient (UNRWA) et par d’autres entités que la mortalité infantile chez les réfugiés palestiniens a considérablement baissé. Cependant, elle ne diminue plus. Des mesures permettant de remédier aux causes les plus probables – mariage et grossesses précoces, mauvaises conditions socioéconomiques et accès limité à des soins périnataux de qualité – sont nécessaires.

Resumen

Objetivo

Presentar los datos procedentes de una encuesta sobre mortalidad en menores de un año realizada en 2008 en Jordania, el Líbano, la República Árabe Siria, la Franja de Gaza y Cisjordania y analizar las tendencias de dicha mortalidad entre los refugiados palestinos en el periodo comprendido entre 1995 y 2005.

Métodos

Tras el procedimiento del nacimiento anterior, se preguntó a las madres que registraron un nuevo nacimiento si el hijo anterior seguía vivo o si había fallecido, el día en que nació el niño y la fecha de nacimiento del neonato cuyo nacimiento se estaba registrando. A partir de esta información se calcularon los índices de mortalidad en niños, bebés y neonatos. La edad de defunción para la mortalidad de niños se estableció a través del intervalo medio entre nacimientos consecutivos y la edad media de los neonatos en el momento de su registro.

Resultados

En el periodo comprendido entre 2005 y 2006, la mortalidad en menores de un año entre los refugiados palestinos osciló entre las 28 defunciones por cada 100 000 recién nacidos vivos de la República Árabe Siria y las 19 defunciones del Líbano. En consecuencia, la mortalidad en menores de un año entre los refugiados palestinos se encuentra entre las más bajas de Oriente Próximo. No obstante, la mortalidad en menores de un año ha dejado de descender en los últimos años, aunque sigue estando a un nivel compatible con la consecución del Objetivo de Desarrollo del Milenio 4.

Conclusión

Gracias, en gran parte, a la asistencia sanitaria primaria que ofrecen el Organismos de Obras Públicas y Socorro (OOPS) de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiados de Palestina en Oriente Próximo y otros organismos, la mortalidad en menores de un año ha descendido con regularidad entre los refugiados palestinos. No obstante, ha dejado de descender. Es necesario aplicar medidas para abordar las causas más probables de esta situación: matrimonio y maternidad a edades tempranas, mala situación socieconómica y acceso limitado a una buena asistencia perinatal.

Резюме

Цель

Представить данные исследования младенческой смертности, проведенного в 2008 году в Иордании, Ливане, Сирийской Арабской Республике, а также на Западном Берегу реки Иордан и в Секторе Газа и проанализировать тенденции в области младенческой смертности среди палестинских беженцев в 1995–2005 годах.

Методы

В соответствии с ранее принятым методом регистрации рождений, у матерей, регистрировавших новорожденного, спрашивали, жив или умер ее предыдущий ребенок, дату рождения этого ребенка и дату рождения регистрируемого новорожденного. На основе этой информации производились оценки смертности среди новорожденных, детей в возрасте до 1 года и ранней детской смертности. Возраст смерти применительно к ранней детской смертности определялся по среднему интервалу между последовательными рождениями и среднему возрасту регистрируемых новорожденных.

Результаты

В 2005–2006 годах младенческая смертность среди палестинских беженцев варьировала от 28 случаев смерти на 100 000 живорождений в Сирийской Арабской Республике до 19 в Ливане. Таким образом, показатель младенческой смертности среди палестинских беженцев является одним из самых низких на Ближнем Востоке. Несмотря на это, в последние годы снижение младенческой смертности прекратилось, хотя ее показатель остается на уровне, совместимом с достижением Цели ООН Nº 4 в области развития, сформулированной в Декларации тысячелетия.

Вывод

В значительной мере благодаря первичной медико-санитарной помощи, предоставляемой Ближневосточным агентством Организации Объединенных Наций для помощи палестинским беженцам и организации работ (БАПОР) и другими специализированными учреждениями, младенческая смертность среди палестинских беженцев последовательно сокращалась. Однако больше она уже не снижается. Необходимы меры по устранению наиболее вероятных причин этого, к числу которых относятся раннее вступление в брак и раннее деторождение, плохие социально-экономические условия и ограниченный доступ к качественной перинатальной медико-санитарной помощи.

ملخص

الغرض عرض معطيات مسح وفيّات الرضّع لعام 2008 الذي أُجري في الأردن، ولبنان، والجمهورية العربية السورية، وقطاع غزة، والضفة الغربية وتحليل اتجاهات وفيّات الرضّع بين اللاجئين الفلسطينيين في الأعوام 1995-2005.

الطريقة في أعقاب طريقة الولادة السابقة، سوئلت الأمهات اللاتي يجري تسجيلهن في ولادات جديدة إذا كان أطفالهن السابقين أحياءً أم أموتاً، وتاريخ ولادتهم، وتاريخ ولادة الولدان الذين تُسجَل ولادتهم. ومن هذه المعلومات جرى تقدير معدلات وفيات الولدان، والرضّع، والأطفال. وجرى تحديد العمر عند الوفاة للوفيات المبكّرة للأطفال عن طريق حساب متوسط الفترات بين الولادات المتعاقبة ومتوسط عمر الولدان عند التسجيل.

النتائج في عامي 2005-2006، تراوح معدل وفيات الرضّع بين اللاجئين الفلسطينيين بين 28 وفاة لكل 100 ألف مولود حيّ في الجمهورية العربية السورية و19 وفاة في لبنان. وبهذا يُعدُّ معدل وفيات الرضّع بين اللاجئين الفلسطينيين من بين أقل معدلات الوفيات في الشرق الأدنى. إلا أن انخفاض معدل الوفيات قد توقف في الأعوام الأخيرة، مع أنه ظل في مستوى يتلاءم مع بلوغ المرمى الرابع من المرامي الإنمائية للألفية.

الاستنتاج لقد ظل معدل وفيات الرضع بين اللاجئين الفلسطينين في انخفاض مستمر ويعود ذلك بدرجة كبيرة الى الرعاية الصحية الأولية التي توفّرها وكالة الأمم المتحدة لإغاثة وتشغيل اللاجئين الفلسطينيين في الشرق الأدنى والجهات الأخرى. إلا أن هذا الانخفاض قد توقف. وهناك حاجة لاتخاذ تدابير لمواجهة الأسباب المحتملة وراء ذلك - كالزواج والحمل المبكّرين والأحوال الاجتماعية والاقتصادية الفقيرة والقدرة المحدودة للوصول إلى الرعاية المناسبة في فترة ما حول للولادة.

摘要

目的

旨在展示从2008年在约旦、黎巴嫩、阿拉伯叙利亚共和国、加沙地带和约旦河西岸进行的婴儿死亡率调查得出的数据,并分析1995-2005年巴勒斯坦难民中婴儿死亡率的趋势。

方法

沿袭之前的生育技术,母亲们在为新生儿进行出生登记时会被问及上一个孩子是否存活、孩子的出生日期以及孩子出生登记的日期。通过这些信息估测出新生儿、婴儿和幼儿的死亡率。幼儿死亡率的死亡年龄由母亲相继生育的平均时间间隔和婴儿出生登记时的平均年龄决定。

结果

2005-2006年,巴勒斯坦难民中婴儿死亡率在阿拉伯叙利亚共和国每10万活产婴儿中的28例死亡和黎巴嫩每10万活产婴儿中的19例死亡的范围内变化。因此,巴勒斯坦难民中的婴儿死亡率在近东地区是最低的。然而,尽管巴勒斯坦婴儿死亡率处于千年发展目标4相适应的水平,但近年来婴儿死亡率下降已停止。

结论

主要由于联合国难民救济及工程处(UNRWA)为近东地区和其他实体的巴勒斯坦难民提供了初级卫生保健,巴勒斯坦难民中的婴儿死亡率才持续下降。然而,近年来这一比率却不再下降。需要采取措施解决的是可能由早婚早育、不良的社会经济条件和无法获得良好的围产期保健等原因引起的问题。

Introduction

Sixty years have passed since about 900 000 Palestinians fled their land. This event affected all countries near Palestine and generated the oldest and largest protracted refugee population in the world.1

Throughout the decades that have transpired since that event, Palestine refugees have enjoyed different levels of access to health-care services in their host countries. However, in many places they face discrimination and are a socially and economically vulnerable population2,3 whose main primary health-care provider continues to be the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. Today this agency serves almost 5 million beneficiaries in Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, territories whose young populations have high fertility rates. UNRWA delivers comprehensive primary health care, among other services, and it focuses particularly on maternal and child health, with targeted activities from preconception4 throughout gestation and the post-delivery period.

Mortality among children within the first year of life (i.e. infant mortality) is an important indicator of the health status of a population and correlates strongly with more comprehensive measures of health, such as disability-adjusted life expectancy.5 Although infant mortality surveys are carried out periodically within countries hosting Palestine refugees, distinguishing between refugee and non-refugee populations is difficult2 and the use of different survey methods by the countries makes it hard to perform comparisons and to assess trends across countries over time.

This paper presents the results of an infant mortality survey conducted by UNRWA in 2008 in Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank and compares them with the results of two earlier UNRWA studies performed with identical methods.6 The trends presented in this paper in infant and early child mortality among Palestine refugees in the Near East for the 10-year period from 1995 to 2005 have never been published before.

Methods

In 2008, we conducted a cross-sectional survey to estimate infant mortality among Palestine refugees served by UNRWA. The preceding birth technique7 was adopted so that the results could be compared with those of two identical surveys conducted by UNRWA in 1997 and 2003.6 Using the infant mortality rates reported in the previous UNRWA surveys,6 we calculated the minimum sample size needed in each UNRWA field of operation to estimate infant mortality to the nearest 5 deaths per 1000 live births with a confidence level of 95%. Beginning on 15 February 2008, we interviewed women who were registering the birth of a neonate (index birth) at UNRWA primary-health-care facilities and who had given birth to at least one other child, until the required sample size was attained. The data collection period varied between countries, however, since the number of newly registered infants in a given period was different in each. Data collection lasted approximately 4.5 months in Jordan, 9 months in the Syrian Arab Republic and the West Bank and 12.5 months in Lebanon. Because data in the Gaza Strip were collected twice to validate the preliminary results, data collection there took 15 months. The compiled survey forms were transferred to the UNRWA Health Department in Amman, Jordan, where the data were entered, cleaned and analysed using EpiInfo 2000 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, United States of America).

Following the preceding birth technique, which is used to indirectly estimate infant and early child mortality (defined here as death within the first three years of life), we asked women whether the preceding child (i.e. the last one born before the index birth) was still alive or not. If they reported that the preceding child was dead, we asked them the age of the child at death and the main cause of death. We also asked the date of birth and sex of the preceding child; the date of birth, age at registration and sex of the neonate, and the mother’s age, parity, residence and level of education.

From the information provided by the mothers we calculated the mean interval between current and preceding births (mean birth interval), the proportion of preceding children who had died by the time of registration and the mean neonatal age at birth registration. We then estimated neonatal, infant and early child mortality rates. The age at death for early child mortality (age “q”) depended on the interval between the index birth and the preceding birth and the age at registration of the index child. Because this estimated age at death differed slightly between Jordan (2.5 years), Lebanon (3 years), the Syrian Arab Republic (2.7 years) and the Gaza Strip and the West Bank (2.5 years each), the main focus of the paper is on neonatal and infant mortality, although the findings for older ages are also presented. We also calculated the frequency of different causes of infant death.

We excluded from the study mothers whose preceding pregnancy had ended in stillbirth but compensated for this by applying a corrective factor of 1.09 when calculating mortality rates, as required by the preceding birth technique.8 If the preceding pregnancy had ended in abortion, we obtained information on the previous child.

The preceding birth technique makes it unnecessary to ask an infant’s exact date of death. Since birth registration coverage in UNRWA clinics is high – already in 2003, over 95% of infant births were being registered within 6 weeks of delivery – the preceding birth technique seemed appropriate for the study setting. The method is a valid alternative to prospective analysis when conducting household surveys is complicated or unfeasible, as is the case among Palestine refugees, who live mostly outside refugee camps and are difficult to target. The technique was modified in 1997 to categorize the time of a child’s death as follows: during the first month, neonatal death; between months 1 and 12, postneonatal death; and within 1 year, infant death.6

Results

We sampled 14 202 neonates registered by UNRWA in 2008. They were distributed among fields as shown in Table 1. The sexes were equally represented and the mean neonatal age at birth registration was less than one month in all fields, although intrasample variations were wide. The mean interval between the birth of the neonates and of the preceding children is shown in Table 2.

Table 1. Size, sex and age at registration of the sample population by field of operations of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, 2008.

| Field | Sample | Males (%) | Mean age (days) at registration (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan | 3461 | 1679 (48.5) | 21.7 (± 22.2) |

| Lebanon | 1776 | 902 (50.9) | 14.3 (± 13.3) |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 3128 | 1542 (49.3) | 15.5 (± 13.8) |

| West Bank | 2130 | 1078 (50.7) | 21.8 (± 16.4) |

| Gaza Strip | 3707 | 1895 (51.1) | 8.1 (± 5.2) |

SD, standard deviation.

Table 2. Death rate among children preceding the youngest neonate in birth order, mean interval between births and reference time, by field of operations of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, 2008.

| Field | Deaths in preceding children |

Mean birth interval (months) | Reference timea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | Corrected %8 | |||||

| Jordan | 81 | 2.3 | 2.55 | 36.9 | Jan 2006 | ||

| Lebanon | 34 | 1.9 | 2.09 | 43.7 | Aug 2005 | ||

| Syrian Arab Republic | 85 | 2.7 | 2.96 | 40.5 | Nov 2005 | ||

| West Bank | 41 | 1.9 | 2.10 | 36.2 | Jan 2006 | ||

| Gaza Strip | 77 | 2.1 | 2.26 | 36.8 | Jan 2006 | ||

a Month and year that the mortality estimates refer to, calculated from the mean birth interval and the mean age of the youngest neonate at the time of registration.5

Globally, 318 deaths were recorded and 291 of them occurred within the first year of life. Infant mortality among Palestine refugees during 2005–2006 ranged from 19.0 deaths per 1000 live births in Lebanon to 28.2 per 1000 in the Syrian Arab Republic. Early child mortality, as per age “q,” ranged from 20.8 per 1000 live births in Lebanon to 29.6 per 1000 in the Syrian Arab Republic (Table 3).

Table 3. Neonatal, post-neonatal, infant mortality and early child mortality among Palestine refugees, by field of operations of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, 2008.

| Field | Mortality |

Age (years) at death (age “q”)b | Mortalitya at age “q” (CI) | Infant mortalitya in host countries9,10 | MDG 4 benchmarka | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatala | Post-neonatala | Infanta (CI) | |||||||||

| Jordan | 15.1 | 7.5 | 22.6 (17.3–28.3) | 2.5 | 25.4 (18.6–33.4) | 22.0 | 22.0 | ||||

| Lebanon | 14.1 | 4.9 | 19.0 (12.6–25.9) | 3.0 | 20.8 (13.0–30.9) | 27.0 | 21.3 | ||||

| Syrian Arab Republic | 17.4 | 10.8 | 28.2 (21.5–34.6) | 2.7 | 29.6 (21.9–38.0) | 16.0 | 20.0 | ||||

| West Bank | 15.4 | 4.1 | 19.5 (13.8–25.3) | 2.5 | 21.0 (14.1–29.5) | 24.0c | 22.0c | ||||

| Gaza Strip | 12.0 | 8.2 | 20.2 (15.2–25.5) | 2.5 | 22.6 (16.2–29.9) | ||||||

CI, confidence interval; MDG, Millennium Development Goal.

a Per 1000 live births.

b Age “q” is the oldest age at death as estimated by the preceding child technique. It is determined from the birth interval between the index birth and the preceding birth and the age at registration of the index child.

c Data refer to the entire territory of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.

Source: Infant mortality in host countries and MDG 4 benchmark were compiled from UN MDG9 and UNICEF.10

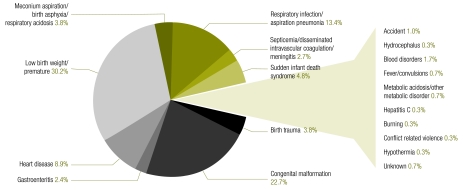

The three main causes of death in the first year of life among Palestine refugees were conditions related to low birth weight or prematurity (30.2%), congenital malformations (22.7%) and respiratory infections (13.4%). Some deaths were also caused by preventable conditions such as birth trauma and hypothermia (Fig. 1). Birth trauma deaths were relatively frequent; they accounted for almost 4% of all infant deaths and for approximately 5% of all neonatal deaths. One death due to hypothermia was documented during the survey. Almost 5% of infant deaths were attributed to the sudden infant death syndrome; 43% of these sudden deaths occurred in the neonatal period and 57% in the post-neonatal period.

Fig. 1.

Infant deathsa among Palestine refugees by cause and field of operation of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, 1995–2005

a Infant deaths recorded during this study totalled 291.

Between 59% and 74% of Palestine refugee infants died during the first month of life. Almost half (43.2%) of these neonates died from causes related to low birth weight or prematurity. Communicable diseases, primarily respiratory infections (10.4%), septicaemia/meningitis (3.1%) and gastroenteritis (0.5%), accounted for 15% of all neonatal deaths. Postneonatal infant deaths were mainly caused by congenital malformations (29%) and communicable diseases (30%), among which the three leading causes were respiratory infections (20%), gastroenteritis (6.2%) and septicaemia/meningitis (1.0%).

Although in the five UNRWA fields of operation we studied, infant mortality rates differed from the rates found in the 2003 survey, none of the differences was statistically significant.

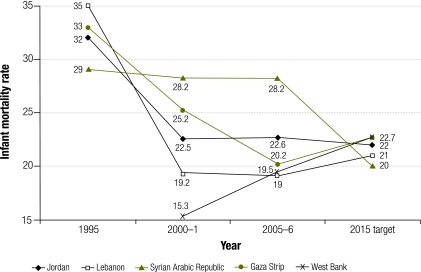

After infant mortality dropped sharply between 1995 and 2001 in Jordan, Lebanon and the Gaza Strip (according to the previous UNRWA surveys), by 2005–2006, the timeframe to which the present survey results can be attributed, rates had stabilized at the levels required to meet MDG 4 (Fig. 2). Only the West Bank experienced a slight, non-significant increase in infant mortality with respect to 2003. If current infant mortality rates are maintained, the MDG 4 target for infant mortality will be met by the Palestine refugee communities in Lebanon, in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. In Jordan this target seems well within reach, while the Syrian Arab Republic appears to be lagging behind.

Fig. 2.

Infant mortality rates (per 1000 live births) among Palestine refugees according to United Nations Relief and Works Agency surveys for 1997, 2003 and 2008

In the decade from 1995 to 2005 early child mortality in the Palestine refugee community followed the same general trend observed for infant mortality:11 a slight increase was observed only in the West Bank. However, because the interval between births has increased progressively during this period, the “q” time frame does not overlap exactly. Thus, more in-depth comparisons cannot be drawn.

Discussion

In recent years, the factors associated with a drop in mortality have been better defined through research. It is now widely acknowledged that some of the most important factors for lowering mortality are public policies targeting disease prevention and control and a viable health sector. Organized political efforts seem to have a direct effect on health, one that is largely independent of income or living standard.12 Although Palestine refugee communities face socioeconomic hardship and have high fertility rates, their infant and childhood mortality rates are among the lowest in the Arab world.6 Remarkably, however, this has been achieved despite the lack of a strong state in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank and despite limited access to public services in host countries such as Lebanon.

In the countries and reference period we have examined, infant mortality rates among Palestine refugees and non-refugee populations were very similar9 (Table 3). The sole exception is the Syrian Arab Republic, whose official infant mortality rates were lower than the rate in the refugee population. These findings support those of previous studies that recognized the impact of UNRWA’s long-standing organized efforts to decrease infant mortality.12

While there is essentially no difference between the infant mortality rates seen among refugee and non-refugee communities in Jordan, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, in Lebanon the infant mortality rate appears to be lower among refugees than among non-refugees (19 versus 27 deaths per 1000 live births). Given that the number of deaths in these populations is small and that survey methods are different, even though the infant mortality rate among non-refugees in Lebanon exceeds the upper confidence interval found for refugees, this observation should be made with caution.

Assessing the health status of the Palestine refugee population in territories of the Near East is made difficult by the lack of appropriate comparators, even when a single, clear indicator such as infant mortality is employed. On one hand, the current survey showed that the causes of neonatal mortality among Palestine refugees are proportionally similar to those found in the most developed regions of the world.13 Non-communicable diseases are the leading causes of infant, and particularly neonatal deaths, among Palestine refugees, as they are among industrialized countries in Europe and North America. Thus, the epidemiologic profile of the Palestine refugees is not typical of the Near East.14 On the other hand, the refugee population is hard to reach and socioeconomically disadvantaged, facts that must be kept in mind to avoid misconceptions. Whereas in highly industrialized countries reductions in child mortality reflect effort and investment on the part of national health systems, Palestine refugees receive health care in a fragmented and unequal fashion across host countries, with the main common health-care provider being UNRWA. Keeping child mortality at low levels will require addressing some of its root causes in the Near East, namely, socially determined patterns of marriage and childbearing, the social and economic determinants of health and limited access to secondary- and tertiary-level hospital care. This is a daunting endeavour, particularly in those States or territories where governments are less directly involved in providing health care for Palestine refugees.

Some of the leading causes of infant deaths found in the survey, such as low birth weight or prematurity and congenital malformations, overlap somewhat and are associated with certain known determinants, including early pregnancy15 and consanguineous marriage.16,17 Most Palestinian women marry young and begin bearing children right away.2 Teenage pregnancies are high risk. Fortunately, they are declining, but in the Near East they continue to contribute to maternal morbidity and mortality.18. Moreover, consanguineous marriages are extremely common and account for one-fourth of all marriages in Lebanon and almost half of all marriages in Jordan, the Syrian Arab Republic and the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.2 But despite their importance, social patterns of marriage and childbearing are not the only factor to be considered when devising ways to avert infant deaths among Palestine refugee communities. UNRWA’s targeted preventive and curative interventions do not encompass birth delivery itself, which takes place in hospitals in the host countries. The quality of maternal and neonatal care, while beyond UNRWA’s control, is also a determinant of neonatal survival and of infant mortality rates. Nonetheless, information on the quality assessment of maternity and neonatal wards in the Near East is scanty, and even when country data are made available, they focus largely on coverage rather than quality.19 Maternity and neonatal care services have probably been most extensively documented in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. WHO20 and Rahim et al.2 have recently raised concerns regarding the delivery of intrapartum and postpartum care in these areas.

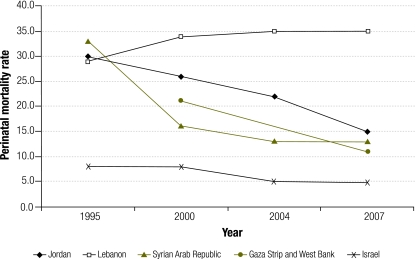

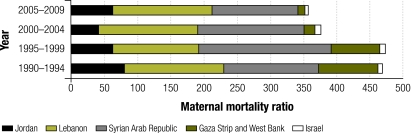

Some may argue that the Gaza Strip and the West Bank represent a worst case scenario on account of the political instability that exists there. However, this is not borne out by perinatal mortality (stillbirths and neonatal deaths occurring in the first week of life) and maternal mortality figures, both of which are indicative of the safety of delivery.13 Perinatal and maternal mortality ratios among the population residing in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank are no worse than in UNRWA’s other fields of operations. As shown in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4, perinatal mortality is highest in Lebanon, and maternal mortality has been consistently higher in Lebanon and in the Syrian Arab Republic than in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank for the past 20 years.

Fig. 3.

Perinatal mortality rate (per 1000 live births) in countries of the Near East, 1995–2007

Sources: Perinatal mortality estimates were compiled from World Health Organization (WHO).13,21,22 As data was not available for the occupied Palestinian territories, the data presented was compiled from: Kalter et al.23 and the WHO Regional Office for the Eastern European.24 Data for 2007 was accessed from WHO Regional Office for the Eastern European,24 Jordan Department of Statistics, USAID, UNICEF, UNFPA DOS25 and for Israeli data WHO Regional Office for Europe.26 Preference where available was given to WHO data for greater comparability. Where necessary for graphical clarification, a mean of values over a time period were provided for a country.

Fig. 4.

Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births) in countries of the Near East, 1990–2009

Sources: Estimates for 1990–94 were compiled from Mahaini27 and WHO/UNICEF.28 Estimates for 1995–99 from Hill et al.29 Estimates for 1995 from WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA30 and Rahim et al.31 Estimates for 2000–04 from WHO32,33 and Mahaini.27 Estimates for 2005–2009 from WHO Regional Office for the Eastern European24,34 and Hill et al.29 Preference where available was given to WHO data for greater comparability. Where necessary for graphical clarification, a mean of values over a time period were provided for a country.

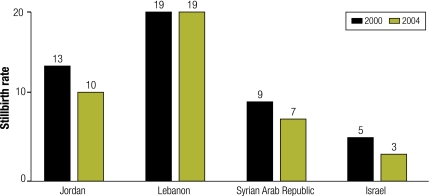

Although poor access to health services seems to be the main contributor to neonatal deaths in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank,2 in Lebanon, with its highly privatized medical sector,35 the medicalization of normal pregnancies is cause for greater concern. The proportion of children delivered by Caesarean section in the country, which was 23% in 2004,36 far exceeds WHO’s recommended maximum of 15%. Lebanon also reports the highest rates of stillbirth (Fig. 5) and perinatal and maternal death in the entire study area. All of this points to the need to monitor the country’s current practices in birth attendance more closely.

Fig. 5.

Stillbirth rate (per 1000 live births) in countries of the Near East, 2000–2004

Source: Stillbirth rates were compiled from reference.13

Study limitations

This study’s main limitation is the potential underestimation of child mortality due to women’s reluctance to acknowledge the death of a child. It is difficult to correct for this. However, we have presented contextual data in the form of trends over time calculated from previous surveys and have compared our estimates with those made by host countries using alternative methods, and yet we found no major discrepancies to suggest a large underestimation of mortality.

Since with the preceding birth technique infant mortality is estimated from the death rate among the children whose birth preceded that of the neonate, a woman could conceivably have lost both the preceding child and the neonate before she could register the most recent birth. This birth would then go unaccounted for in the survey. However, the low mean age at registration (between 8 and 21 days) found in the present study makes this bias unlikely. Another limitation is that the causes of death were reported by the mothers, who may have misunderstood them or not recalled them accurately. Finally, the confidence intervals reported in this paper are quite wide because there were very few infant deaths. This has been discussed in previous publications whose authors applied similar methods.12

Conclusion

The UNRWA and other health-care providers in the Near East have succeeded in delivering to Palestine refugees quality comprehensive primary health care with a strong focus on prevention and maternal and child health. But although strides have been made in the fight against the preventable causes of infant death, such as communicable diseases and undernutrition, the current stagnation in the decline of infant mortality among Palestine refugees in the Near East is worrisome. Comprehensive primary health care is essential in maintaining infant mortality at low levels and in preventing the genetic and pregnancy-related determinants of infant death, but it is not enough. Unless access to high-quality maternity and perinatal services is improved, infant mortality rates are unlikely to decrease substantially in the near future and the tenuous results obtained so far could be readily lost if enduring geopolitical instability jeopardizes continuous access to primary-health-care services in the region.

Acknowledgements

The 2008 survey was a joint effort of the entire UNRWA health programme. We thank field family health officers, field nursing officers, medical officers, staff nurses, as well as the administrative staff in UNRWA headquarters in Amman, Jordan, for their support during the present study.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Protracted refugee situations: the search for practical solutions, 2006. In: The State of the world's refugees. Geneva: United Nations; 2006. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/search?page=search&docid=46822e022&query=palestine%20largest [accessed 13 February 2011].

- 2.Rahim HF, Wick L, Halileh S, Hassan-Bitar S, Chekir H, Watt G, et al. Maternal and child health in the occupied Palestinian territory. Lancet. 2009;373:967–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabatinelli G, Pace-Shanklin S, Riccardo F, Shahin Y. Palestinian refugees outside the occupied Palestinian territory. Lancet. 2009;373:1063–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60101-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. Annual report of the Department of Health 2008. Amman: UNRWA Health Department; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reidpath DD, Allotey P. Infant mortality rate as an indicator of population health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:344–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.5.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madi HH. Infant and child mortality rates among Palestinian refugee populations. Lancet. 2000;356:312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.David PH, Bisharat L, Hill AG. Measuring childhood mortality: a guide for simple surveys Amman: United Nations Children’s Fund, Regional Office for the Middle East and North Africa & London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aguirre A, Hill AG. Childhood mortality estimates using the preceding birth technique: some applications and extensions (CPS Research Paper 87-2). London: Centre for Population Studies & London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 1987.

- 9.We can end poverty 20015; Millenium Development Goals [Internet]. New York: United Nations. Available from: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/ [accessed 13 February 2011].

- 10.UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) [Internet]. Available from: http://www.childmortality.org/ [accessed 15 February 2011].

- 11.United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. Infant and child mortality among Palestine refugee population. Amman:UNRWA Health Department; 2004. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/rhrn/pdf/Infant%20and%20early%20child%20mortality%20among%20Palestine%20refugee%20po.pdf [accessed 13 February 2011.

- 12.Khawaja M. The extraordinary decline of infant and childhood mortality among Palestinian refugees. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:463–70. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neonatal and perinatal mortality: country, regional and global estimates (2000) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/9241563206_eng.pdf [accessed 13 February 2011].

- 14.Statistical annex of the World Health Report 2005 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2005/annex/en/index.html [accessed 13 February 2011.

- 15.Mehra S, Agrawal D. Adolescent health determinants for pregnancy and child health outcomes among the urban poor. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:137–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amitai Y, Haklai Z, Tarabeia J, Green MS, Rotem N, Fleisher E, et al. Infant mortality in Israel during 1950–2000: rates, causes, demographic characteristics and trends. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19:145–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussain R. The impact of consanguinity and inbreeding on perinatal mortality in Karachi, Pakistan. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1998;12:370–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1998.00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahaini R. Improving maternal health to achieve the Millennium Development Goals in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: a youth lens. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14(Suppl):S97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan country profile. Geneva: World Health Organization, Department of Making Pregnancy Safer. Available from: http://www.who.int/making_pregnancy_safer/countries/jor.pdf [accessed 13 February 2011].

- 20.Improving the quality of health care in Gaza Strip, briefing note July 2009 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_health_cluster_quality_program_2009_07_29_english-20090828-094819.pdf [accessed 13 February 2011].

- 21.Perinatal mortality: a listing of available information. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1996/WHO_FRH_MSM_96.7.pdf [accessed 17 March 2011].

- 22.Neonatal and perinatal mortality: country, regional and global estimates 2004 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241596145_eng.pdf [accessed 17 March 2011].

- 23.Kalter HD, Khazen RR, Barghouthi M, Odeh M. Prospective community-based cluster census and case-control study of stillbirths and neonatal deaths in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22:321–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Making pregnancy safer statistics 2007 [web site]. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern European. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/mps/pdf/statistics_2007.pdf [accessed on 17 March 2011].

- 25.Jordan Population and Family Health Survey 2007. Calverton: Department of Statistics [Jordan] and Macro International Inc.; 2008. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADN523.pdf [accessed 17 March 2011].

- 26.Health for all database. World Health Organization European Regional Office. Available from: http://data.euro.who.int/hfadb/ [accessed 17 March 2011].

- 27.Mahaini R. Improving maternal health to achieve the Millennium Development Goals in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: a youth lens. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14(Suppl):S97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Revised 1990 estimates of maternal mortality a new approach by WHO and UNICEF, 1996. World Health Organization (WHO). Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1996/WHO_FRH_MSM_96.11.pdf [accessed 17 March 2011].

- 29.Hill K, Thomas K, AbouZahr C, Walker N, Say L, Inoue M, et al. Maternal Mortality Working Group Estimates of maternal mortality worldwide between 1990 and 2005: an assessment of available data. Lancet. 2007;370:1311–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO maternal mortality in 1995: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2001/WHO_RHR_01.9.pdf [accessed 17 March 2011].

- 31.Rahim HF, Wick L, Halileh S, Hassan-Bitar S, Chekir H, Watt G, Khawaja M. Maternal and child health in the occupied Palestinian territory. Lancet. 2009;14373:967–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Statistics 2005 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/whstatsdownloads/en/index.html [accessed 17 March 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Statistics 2009 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2009/en/index.html [accessed 17 March 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Making pregnancy safer statistics 2004 [web site]. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern European. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/mps/media/excel/Statistics_2004.xls [accessed 17 March 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kabakian-Khasholian T, Kaddour A, Dejong J, Shayboub R, Nassar A. The policy environment encouraging C-section in Lebanon. Health Policy. 2007;83:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Making pregnancy safer statistics in the Eastern Mediterranean Region - 2004 [Internet]. Cairo: World Health Organization, Regional Office of the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/MPS/Statistics_2004.htm [accessed 13 February 2011].