Abstract

Objective:

A discourse analysis was conducted of peer-written blogs about the chronic illness endometriosis to understand how bloggers present information sources and make cases for and against the authority of those sources.

Methods:

Eleven blogs that were authored by endometriosis patients and focused exclusively or primarily on the authors' experiences with endometriosis were selected. After selecting segments in which the bloggers invoked forms of knowledge and sources of evidence, the text was discursively analyzed to reveal how bloggers establish and dispute the authority of the sources they invoke.

Results:

When discussing and refuting authority, the bloggers invoked many sources of evidence, including experiential, peer-provided, biomedical, and intuitive ones. Additionally, they made and disputed claims of cognitive authority via two interpretive repertoires: a concern about the role and interests of the pharmaceutical industry and an understanding of endometriosis as extremely idiosyncratic. Affective authority of information sources was also identified, which presented as social context, situational similarity, or aesthetic or spiritual factors.

Conclusions:

Endometriosis patients may find informational value in blogs, especially for affective support and epistemic experience. Traditional notions of authority might need to be revised for the online environment. Guidelines for evaluating the authority of consumer health information, informed by established readers' advisory practices, are suggested.

Highlights.

Endometriosis patients who blog about the illness may determine authority of information sources through both cognitive and affective methods.

Implications.

Because patients with chronic illnesses might have different authority criteria than medical librarians do, it could be useful to carefully incorporate electronic patient discussion forums, medical blogs written by laypeople, and other nontraditionally authoritative resources into consumer health information selection policies. Standard biomedical resources are certainly important to recommend to consumers, but they do not convey the complete picture of a chronic illness and its related experience.

Patients with chronic illnesses and caregivers can benefit from sources such as blogs and online discussion lists that provide social and emotional support as well as accounts of “lived experience.”

An understanding of the patient's potential epistemological community can make the librarian's recommendations more appropriate for the individual user.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic illness is a context in which people may do a great deal of “information work” [1]. Chronic illnesses are often broad in scope and effect, difficult to diagnose, complex, ever changing, and not amenable to conventional treatments. They often have significant physical, emotional, and social repercussions, and their management requires work by the ill person and those around the ill person, much of which may require considerable time and energy, be mentally and emotionally demanding, and occur beyond doctors' offices [1].

A major barrier to information access expressed by people with chronic illnesses is the difficulty of finding information relevant to their situations [1, 2]. Chronic illness is an important impetus for collaborative information behavior [3, 4]: As do information seekers in other contexts, people with chronic illnesses tend first to seek help or information from people like themselves [5]. Acquaintances with the same disease can provide socially appropriate opportunities to expose a seeker to disease-relevant information and support [6]. The desire for support underlies the creation of resources, services, and groups in which peers physically or virtually “come together to provide emotional and other support through sharing their personal lived experience as well as exchanging other resources” [7]. Participants in health-oriented support groups [8, 9] and online resources such as discussion forums and peer-authored blogs [10] report receiving both informational and emotional support. Illness blogs have many of the advantages of face-to-face peer sources without the stigma of approaching a peer with a personal question [6].

Peer sources may also offer a highly valued and particularly relevant kind of information based on “wisdom and know-how gained through reflection upon personal lived experience” [11] rather than on professional knowledge. Experiential knowledge “consists of the statements, stories or narratives reflecting some aspect of an individual's experience that she or he values and trusts as knowledge. To an uninvolved observer, much experiential knowledge may sound like or appear to be small talk or everyday conversation” [11].

The significance of experiential knowledge for people with chronic illnesses poses particular challenges for information professionals, who are schooled in selecting traditionally authoritative resources and employing evidence-based techniques for evaluating health information sources. Selection criteria for a health sciences journal include, among other things, its perceived “scholarly” status, its publisher, the affiliations of the journal's authors and editors, and its impact factor [12]. Health sciences monograph selection tools consist of resources such as core lists, vendors, and book reviews in medical journals [13]. Guidelines for consumer health information collection development focus on patient education literature written by health professionals, as well as by patient advocacy and professional organizations. Consumer-oriented library materials might also include general medical reference books [14]. These and other standard evaluation criteria assume that the most authoritative resources are authored by health care professionals and researchers. However, people with chronic illnesses may use authority criteria that are completely distinct from those that information professionals use [15]. For example, while a blog describing the author's experience with a chronic disease is unlikely to meet librarians' traditional standards for authority, it might be considered very authoritative by someone who is learning to cope emotionally with a new diagnosis [16].

Library and information science (LIS) researchers have long been interested in the ways that individuals and communities evaluate the authority of information sources. The concept of cognitive authority has offered a useful framework for explaining an individual's situated judgments about the authority of information sources [17]. Cognitive authority is a particularly important concept for understanding users' evaluations of web resources [18]. It has been defined by Rieh, following Wilson [17], as “the extent to which users think that the information is useful, good, current, and accurate. Cognitive authority is operationalized as to the extent to which users think that they can trust the information” [18]. More recently, LIS researchers have adopted new approaches to the study of authority that consider not the cognitive processes by which an individual makes decisions about an information source, but the social practices whereby a community collaboratively negotiates what counts as an authoritative information source [19–21]. Depression patients were found to rely on a wide range of resources, while using personal, experiential knowledge as confirmation of treatment effectiveness [20]. A study of the ways that members of a chronic illness community collectively filter, interpret, evaluate, and synthesize as they share can provide insight into the ways that authority is developed and challenged in that community [4]. Studies such as this can provide practitioners with new ways of thinking about the criteria they use when evaluating or recommending peer sources for chronic illness.

This article analyzes the ways that peer bloggers with endometriosis present information sources and make cases for and against their authority. Endometriosis is an enigmatic chronic disease that causes uterine tissue implantation in areas other than the uterus. Highly underdiagnosed, it may affect up to 25% of reproductive-age women. Symptoms vary widely, but the most frequent complaint is pelvic pain, and endometriosis is a cause of common infertility. The broad spectrum of presentation and symptoms, as well as the absence of satisfactory treatments, leaves patients largely at a loss for information that they perceive as reliable [22]. For these reasons, Whelan characterizes women with endometriosis who work together to find answers as an “epistemological community” [23]. This analysis will show how bloggers' justification strategies draw on understandings that members of their specific epistemological community commonly hold.

Blogs authored by people with chronic illness are of particular interest to LIS researchers, because they provide naturalistic sources of data about the blogger's illness-related information work [2], including selection, justification, evaluation, and interpretation of information identified by the blogger from other sources. Comments and links on blogs provide evidence of what Talja and Hansen call a “community of sharing” [4], a group of people who develop shared understandings and create knowledge structures that may in turn be used by others. Blogs allow both members and nonmembers of epistemic cultures to interact in dialogue and to participate in the culture [24]. They therefore offer the possibility of extending the face-to-face social networks that Veinot [6] has shown to mediate information validation. LIS researchers have begun to study social and community aspects of health- and illness-related information work [6, 25–27]. Important findings about the readers of illness blogs have been identified [10]. However, there has so far been little consideration of what the blogs themselves can tell librarians and researchers about how people living with chronic illness evaluate information sources.

METHODS

The chosen method begins from the perspective that the criteria for evaluating information sources are collective, not individual [28]. Practices such as framing information needs and evaluating information sources are therefore always situated within social relationships and involve tacit knowledge of the conventions and procedures shared and developed by members of the community [4].

Sample

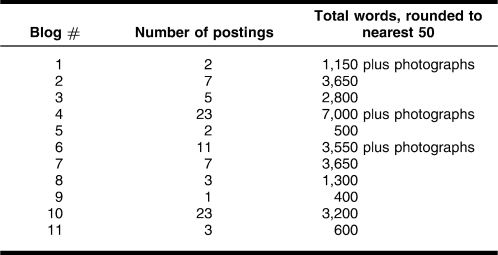

Eleven blogs were selected, authored by women living with endometriosis and focused exclusively or primarily on their authors' experiences of endometriosis. Beginning with one prominent chronic illness blog, successive links were searched until all known endometriosis blogs had been identified. Bloggers who incorporated experience with multiple chronic illnesses, as well as bloggers with endometriosis who mainly posted about infertility, were excluded. Posts from each blog for the same 2-month period were captured. Frequency and length of postings varied substantially across blogs, as can be seen in Table 1. In total, the data set consisted of 87 posts, comprising nearly 27,500 words.

Table 1.

Frequency and length of endometriosis blog postings, November–December 2009

As Table 1 shows, blogs varied in the number and length of posts. They also varied in scope and content. Some were very broad, describing endometriosis symptoms and treatments and personal and family happenings. Others were more focused on the illness. There was also substantial variation in the kinds of things happening in bloggers' lives during the data collection period. Those who posted the most content described major life events such as weddings, job changes, infertility treatments, pregnancy loss, and birth. Because each blogger chose to publish her posts, the blogs were viewed as publicly available information, but the bloggers have been de-identified in this article.

Analysis

Potter's discourse analytic approach was used to analyze how bloggers described, supported, or challenged the authority of information sources [28, 29]. Discourse analysis sees language not as a transparent medium for conveying meaning, but as constructed within a particular community and a broader social context [30]. Potter's approach focuses on the ways that speakers and writers assemble their versions of the world. It therefore provides insight into the ways that concepts such as “normal,” “appropriate,” and “authoritative” are negotiated within epistemological communities and is particularly well suited for analyzing the ways that the authority of information sources is presented, challenged, and defended [31]. This approach has been widely used in both health sciences [32–36] and LIS [19–21, 28, 29, 37–43].

Discourse analysis requires close study of the details of actual language use and the construction of accounts, both within and across instances, to identify the discursive building blocks (“interpretative repertoires” [29, 44]) that bloggers use to represent information sources. The analysis thereby makes it possible to identify coherent patterns that exist across bloggers and that provide evidence of broader community practices and conventions in which collaborative information behavior operates in this context. The goal is not to show how frequently a particular strategy is used or to produce a generalizable analysis, but rather to show how members of a community, in this case the endometriosis blogging community, make cases for the authority—or lack thereof—of the sources they describe and how they then use that authority to lend support to claims they make themselves.

The analysis was done in several iterative stages. First, each author read the entire corpus and individually identified instances in which the bloggers discussed information sources [21]. In effect, the authors looked for the lay equivalent of citations in scholarly writing. For example, phrases such as “told me that,” “found out,” “according to,” “said,” or “I read/heard/saw” were attended to, and statements that a blogger knew something to be true or explained how or why she knew it to be true were considered.

Next, the authors individually analyzed the rhetorical strategies that bloggers used to present or challenge the authority of information sources. They looked systematically for the interpretative repertoires underlying bloggers' accounts and considered how bloggers used “category entitlements” [29, 45], the idea that certain categories of people are treated as knowledgeable by virtue of membership in that category. They met regularly to compare their individual analyses, to look for confirming and disconfirming examples, and to analyze the functions performed by bloggers' accounts (e.g., undermining authority, making claims or counterclaims) until they had identified and agreed on the major techniques. Together, they selected examples that provided the clearest representations of these techniques to include in the final article. Because discourse analysis involves the presentation of the data, the reader provides the final assessment of the faithfulness of the interpretation.

RESULTS

Representations of cognitive authority

The bloggers in the sample invoked biomedical forms of knowledge (e.g., health care providers, the biomedical literature), experiential knowledge (including their own bodies, instincts, and their personal experience as well as information gleaned from the face-to-face and online endometriosis communities), and spiritual and intuitive sources of information. As studies of other health information seekers have found [19–21], this study found that endometriosis bloggers made and disputed claims about the cognitive authority of multiple forms of knowledge and of their associated information sources.

When bloggers invoked a source, a common strategy was to draw directly or indirectly on its category entitlement. Referring to the category entitlement removes the need to ask how the person knows; instead, simply being a member of some category—doctor, hockey player, person with endometriosis—is treated as sufficient to accept their knowledge of a specific domain [31]:

I spoke with my gynecologist about the issue at my annual a few weeks ago. [Blogger 6]

Many thanks to [name], moderator of the [XXX] email list, for finding this hair-raising story. [Blogger 3]

The category entitlement of biomedical sources was commonly expressed simply by invoking the category (“my doc”), by identifying the medical specialty, or by providing specific professional detail. The following example provides partial bibliographic details and a characterization of the journal as “medical.” This account looks almost like a scholarly citation:

In Volume 1, No. 1, 2009 edition of the medical journal Human Reproduction a debate paper debuted titled: A call for more transparency of registered clinical trials on endometriosis. This was published by Sun-Wei Gou of Renji Hospital, and the institute of Obstetric and Gynecological Research; Lone Hummelshoj—Secretary General of the World Endometriosis Society. [Blogger 2]

Bloggers used parallel characteristics (role, biographical detail) for justifying the category entitlement of experiential sources. Here, women's experiences with side effects were presented as evidence of their experiential entitlement to speak authoritatively about the relative merits of two drugs:

I have been doing some research though on the cancer drug Femera for endometriosis…. I've been reading forums where women have taken both that and Lupron and claim the side effects were MUCH more tolerable on Femera than Lupron. [Blogger 2]

Words that highlight experience (e.g., “familiar,” “not the first time”) and specific details (e.g., about the location of pain) served as evidence to support a blogger's own authority claim [31]:

I got that familiar feeling, and no, it was nothing good…. It was the familiar pain of having endometriosis. The pain was located in the exact spots that I've had the pain before. [Blogger 1]

The bad news is that my instincts were right, and my body simply does not perform on command. [Blogger 6]

With this understanding in mind, it is possible to see how elements of postings that look like “small talk or everyday conversation” [11], such as the bloggers' own biographies, become important to establishing their own category entitlement to experiential knowledge. A blogger's medical history had the effect of serving as her experiential curriculum vitae:

I have Stage IV endometriosis. I've always had painful periods, but, was on birth control from early on in my teens to regulate my periods and pain. [Blogger 4]

Two kinds of challenges can be made to category entitlements. First, the authority of the entire category can be called into question. In the endometriosis blogging community, the uncertainty around the disease itself was used quite frequently as evidence against the authority of biomedical sources and, conversely, enhanced the authority of the knowledge of the women themselves:

Endometriosis patients have or will learn at some point that medical science is at a loss as to what exactly causes endometriosis. Yes, they don't know. And because they don't know, they don't really know how to fix it. [Blogger 2]

I think one of the most difficult things for me is conveying to people that even if I am feeling better, I am still well below the level of energy of a healthy adult…. When talking to doctors, doing better or feeling good are usually the only words heard, even if the explanation that follows allows for much greater improvement before “normal” is reached. [Blogger 6]

The second kind of challenge is to the legitimacy of an individual's entitlement to membership in a community. This technique takes the form of a critique of a specific individual that stops short of critiquing an entire category:

I had a chance to speak with my [medical specialist] this week about the strange and unpleasant reaction I have to [class of drug]. They (my doctor consulted with a [colleague] who specializes in [relevant area]) have never heard of such a response. [Blogger 6]

As a general principle, invoking an outside source allowed the blogger to present herself as merely presenting the perspective of someone else [31]. This strategy minimizes the speaker's stake in the statement, as the claim then becomes a report from others and cannot be dismissed as merely the speaker's own opinion. Invoking more than one source, particularly if those sources can be demonstrated to be entirely independent of one another, can strengthen a claim, such as when personal accounts or embodied experience validate medical opinion:

There is literature touting the benefits and negatives of [a specific] therapy, as well as a plethora of personal accounts to be found on-line as to both. [Blogger 2]

All in all I'm feeling really good these days! Every once in a while I'll have a painful day, but they are not frequent at all, thank goodness. Whatever my doc did this last Lap seems to have worked. [Blogger 5]

Conversely, one category entitlement might be pitted against another. A particularly effective strategy is a comparative evaluation that builds up the authority of one source, at the same time that it challenges the authority of another [31]:

I think our RE [reproductive endocrinologist] is too conservative. I am reading about bloggers whose RE's transferred 3–5 eight-celled good to excellent embryos. Ours said “no way” to three! [Blogger 10]

Two interpretative repertoires underlay many of the authority claims bloggers made. The first was built on a concern about the role and interests of the pharmaceutical industry in driving endometriosis research and treatment. The suggestion that individual doctors might be unduly influenced by “Big Pharma” was a very effective strategy for challenging biomedical perspectives that might otherwise be unassailably authoritative:

Patents are pending for this… technology in the United States. But I wonder, will [drug company] merely use this new technology as a platform to reach more endometriosis patients with their medication? … will doctors begin pushing yet another drug onto already frustrated endometriosis patients. [Blogger 2]

The second interpretative repertoire bloggers used was underpinned by an understanding of endometriosis as so idiosyncratic that each woman's experience is unique. This repertoire strengthened critiques of one-size-fits-all sources and justified information seekers' strategies of searching out other women whose symptoms and situations were similar to theirs:

This med has about a 60% effectiveness. You all know how I feel about statistics these days. I'm always the minority 1–2% it seems lately. [Blogger 4]

Some people experience horrific side effects with GnRH agonists—some lasting for years after stopping therapy—while others swear by the medication and wish they could take them continuously. Knowing how your body reacts to medications is vital in choosing which medicinal therapy to employ for your battle with endometriosis. And that is a decision that should be made between you and your doctor. [Blogger 1]

Together, these two repertoires presented the woman with endometriosis as needing to advocate for herself and supported the active seeking and sharing of information as part of this advocacy:

If you are a regular reader… then you will know how adamant I, and other endometriosis bloggers, have been about the need for clear transparency when it comes to endometriosis drug trials. [Blogger 2]

Representations of affective authority

In addition to making claims about the cognitive authority of sources, the authors found that bloggers made and contested claims for what might be called affective authority, the extent to which users think the information is subjectively appropriate, empathetic, emotionally supportive, and/or aesthetically pleasing. Affective authority claims were made on different bases than cognitive authority claims. Three characteristic ways of making affective claims were identified: First, social context played a crucial role, and sources with long-term and/or intimate knowledge of the blogger's context were presented as providing more personal and therefore more emotionally supportive information. Authority claims of this sort rested not on the category entitlement of a group of people, but rather on the unique characteristics of an individual member. In the next example, a blogger reports using affective criteria to make a decision that seems to make little cognitive sense:

I have given this [drug] its fair shake. I really have. In the past, and if this had been my old doctor who I had built a long relationship with, I would have given up on the med a long time ago. But, because this is a new, budding relationship I'm trying to foster, I gave it a go. I stuck with it despite the hell it's brought me. Headaches. Nausea. And no relief. [Blogger 2]

Second, bloggers identified similar experiences as a criterion for a source's affective as well as cognitive authoritativeness:

Which brings me to my blog. I am thankful to have a place where there are others who understand how bad it can get, how wonderful the small (by normal standards) accomplishments are. [Blogger 6]

You know what's the worst—when you mention “infertility” and everyone (I mean Everyone) says “oh you never know what could happen…don't give up on it…it's when you stop trying that it will happen…” I mean, do they even know what I'm talking about? How can one say something like that when they don't know the full details? Hope is a very sensitive thing. [Blogger 7]

I went to lunch with my dear friend… today. We have so much in common and always have a great time sharing our lives catching up. [Blogger 8]

For many bloggers, gestational motherhood was a very important goal. For those undergoing fertility treatment, stories from others who had had positive experiences offered encouragement:

I found this great article about a couple who know our pain and have walked in our shoes…. The story made my eyes water. [Blogger 10]

However, when a woman had difficulty conceiving or experienced pregnancy loss, these very sources became a source of deep discouragement.

Why do I personally know 4 people that are having babies within 1–2 weeks of my “due date”? … and many other bloggers (also due around when I was). [Blogger 4]

The online infertility community is deeply sensitive to this consideration, and bloggers prefaced talk about pregnancy, birth, or babies with “spoiler” alerts:

* Warning to my friends with fertility issues, I will be putting a picture or two at the bottom of the post.* [Blogger 1, italics in original]

Finally, aesthetic and spiritual components played into descriptions of affective authority. Sources were described as speaking or writing beautifully, and bloggers highlighted their ability to comfort or inspire rather than the ability to inform:

[Clergy] gave an amazing sermon—it was so personal. He is such a wonderful speaker. We are so thankful that he was there today. [Blogger 4]

The ceremony was short but personal, and very emotional. [Blogger 7]

I'm thankful that God showed me His will… .i had been praying [for a long time] about [question] and even though it took a long time for an answer i know truly and wholeheartedly that i am called to [take a particular course of action]. [Blogger 11]

In my genuine deep despair last week, [partner said something encouraging]. I was speechless. It made me cry. It slightly lifted the fog surrounding my soul. [Blogger 10]

Although recent LIS research has considered affect's roles in information seeking and system design [46], no work has identified affect as a claim to authority. Additional research is needed to further investigate this finding.

DISCUSSION

This study's findings mirror those of other researchers who address both cognitive and affective characteristics of online peer health information services. Postings to breast cancer discussion forums provide detailed accounts of users' personal illness experiences, including related emotional states [26]. The perceived credibility of cancer blogs contributed significantly to readers' problem solving and information seeking, but hosting one's own blog was significantly related to emotion management [7]. This finding suggests that the emotional value that readers experienced might be more related to social engagement than to the content of the blogs themselves. Professional recognition of the ways that information seekers value both cognitive and affective authority has the potential to address the “information work” burden involved in managing chronic illness and its attendant psychological and physical burdens [1, 20, 26, 27].

Researchers and librarians who are evaluating consumer health resources solely using the collection development guidelines and authority determination criteria outlined in this paper's introduction are therefore missing a large part of the story from the users' perspective. The point here is not to set up a hierarchy of evidence or of information sources. Despite their rigor, biomedical understandings are not infallible: Researchers and medical practitioners can make errors, and a study may not tell the whole story. At the same time, a drug that is profitable to a large pharmaceutical company may indeed benefit those who take it, as may folk remedies without a biomedical evidence base. What is important is that interpretative repertoires such as those identified above play out within a community. Attending to the repertoires that lay information seekers use can provide researchers with a more complete understanding of collaborative information validation [6] in a particular epistemological community. Attending to lay representations can also enable professionals to make evaluation decisions that reflect the community's own criteria for collaborative information validation rather than just the librarian's.

It is not suggested here that librarians should abandon evidence-based standards. However, readers are reminded that these are the standards of the scholarly and librarian community and that they may not reflect the standards of the user community. It is known that information seekers in everyday life do not generally make use of professionals' criteria when evaluating online resources [15]. It is also known that the sources that score highest on traditional authority criteria are not the only ones that seekers want. A user-centered approach to evaluating consumer health resources may need to take broader community standards into account.

A strategy for doing so might be borrowed from the readers' advisory literature [47, 48]. Readers' advisors may certainly evaluate the epistemic content of leisure reading material, for example, the physical plausibility of a science fiction universe, or the historical accuracy of a novel. However, they recognize that epistemic content is just one of many factors readers themselves might use to choose a book, including a book's pacing, characterization, storyline, and frame [49]. A similarly broad perspective would allow for a more user-centered evaluation of peer health resources.

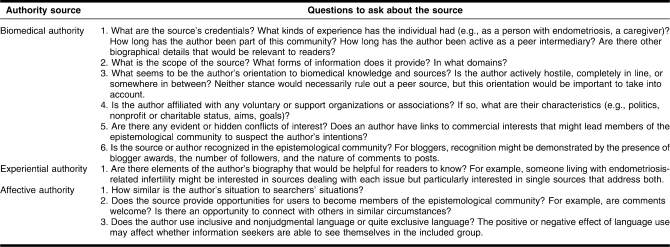

This study's analysis revealed several factors that endometriosis bloggers identified as important to their evaluations of sources. These factors, described in Table 2, offer a starting place for researchers and practitioners who seek to extend their thinking about user-centered evaluation strategies. While biomedical authority is appropriately evaluated by using the strategies familiar to medical librarians, evaluating experiential and affective authority may require some modifications to standard practice.

Table 2.

Potential user-centered evaluative sources of authority for consumer health information

In the end, of course, the most important questions to ask are those that librarians put to their communities of users. What evaluation criteria are important to a community, and how might librarians with consumer health information repositories take these into account when making collection and referral decisions?

Neal provides suggestions for incorporating nontraditionally authoritative resources into the library's consumer health information offerings, with special consideration given to the growing Web 2.0 and mobile telephone influences on the public's information-seeking habits. Ideas include allowing patron-contributed reviews about materials in a library's collection to appear in the online public access catalog (OPAC), creating a library-sponsored social networking profile or wiki that allows patrons to share links and conversations, providing links to multimedia resources and smart phone applications, and explaining the positives and negatives of both traditional and nontraditional resource types to patrons [16].

Limitations of the study

This study offers a very preliminary analysis. It considers only eleven blogs for a limited period of time. For this paper, the authors only analyzed the bloggers' postings and not readers' responses to them. The authors speculate, based on Veinot's findings [6], that readers of these blogs might likewise distinguish between cognitive and affective benefits, but this study does not provide the data to make that claim. The data source further does not allow the authors to make inferences about the motivations of the bloggers themselves. Interviews with bloggers and readers would complement the analysis that has been presented here.

CONCLUSIONS

While peer support tools such as health blogs may not meet librarians' traditional standards for authority, they might provide both the social support and the affectively authoritative and situationally relevant information that information seekers value [16]. Reading or listening to peer accounts and attending to the authority claims and the interpretative repertoires that underlie them offer both researchers and practitioners a tool for developing an understanding of how a specific epistemological community constructs its authority. For researchers, this analysis takes a further step in the study of affective elements of information behavior [46]. For practitioners, it offers possibilities for facilitating user-centered decision making about information resources and programs.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this article was presented at the 38th Annual Conference of the Canadian Association for Information Science/L'Association canadienne des sciences de l'information; Montréal, QC, Canada; June 3, 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hogan T.P, Palmer C.L. “Information work” and chronic illness: interpreting results from a nationwide survey of people living with HIV/AIDS. Proc Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2005;42(1):150–69. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker L.M. A study of the nature of information needed by women with multiple sclerosis. Libr Inf Sci Res. 1996 Winter;18(1):67–81. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foster J. Collaborative information seeking and retrieval. In: Cronin B, editor. Annual review of information science and technology. Vol. 40. Medford, NJ: Information Today; 2006. pp. 329–56. p. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talja S, Hansen P. Information sharing. In: Spink A, Cole C, editors. New directions in human information behavior. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 1996. pp. 113–34. p. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris R.M, Dewdney P. Theory and research on information seeking. In: Harris R, Dewdney P, editors. Barriers to information: how formal help systems fail battered women. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1994. pp. 7–34. p. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veinot T.C. Interactive acquisition and sharing: understanding the dynamics of HIV/AIDS information networks. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2009 Nov;60(11):2313–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borkman T.J. Introduction to the special issue. Am J Community Psychol. 1991 Oct;19(5):643–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00938036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy L. Mutual support groups in Great Britain: a survey. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16(13):1265–75. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottlieb B.H. Social networks and social support in community mental health. In: Gottlieb B.H, editor. Social networks and social support. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1981. pp. 11–39. p. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung D.S, Kim S. Blogging activity among cancer patients and their companions: uses, gratifications, and predictors of outcomes. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2008 Jan;59(2):297–306. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schubert M.A, Borkman T. Identifying the experiential knowledge developed within a self-help group. In: Powell T.J, editor. Understanding the self-help organization: frameworks and findings. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 227–46. p. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson L.L, Higa M.L. Journal collection development: challenges, issues, and strategies. In: Wood M.S, editor. Introduction to health sciences librarianship. New York, NY: The Haworth Press; 2008. pp. 69–96. p. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrigan E, Higa M.L, Tobia R. Monographic and digital resource collection development. In: Wood M.S, editor. Introduction to health sciences librarianship. New York, NY: The Haworth Press; 2008. pp. 97–126. p. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith C.A. Consumer health information. In: Wood M.S, editor. Introduction to health sciences librarianship. New York, NY: The Haworth Press; 2008. pp. 429–58. p. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wathen C.N, Burkell J. Believe it or not: factors influencing credibility on the web. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2002 Jan;53(2):134–44. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neal D. The conundrum of providing authoritative online consumer health information: current research and implications for information professionals. Bull Am Soc Inf Sci Technol [Internet] 2010 Apr/May;36(4):33–7. [cited 9 Jun 2010]. < http://www.asis.org/Bulletin/Apr-10/AprMay10_Neal.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson P. Second hand knowledge: an inquiry into cognitive authority. Westport, CT: Greenwood; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieh S.Y. Judgment of information quality and cognitive authority in the web. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2002 Jan;53(2):145–61. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKenzie P.J. Justifying cognitive authority decisions: discursive strategies of information seekers. Libr Q. 2003 Jul;73(3):261–88. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliphant T. “I am making my decision on the basis of my experience”: constructing authoritative knowledge about treatments for depression. Can J Inf Libr Sci. 2009 Sep–Dec;33(3/4):215–32. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKenzie P.J, Oliphant T. Informing evidence: claimsmaking in midwives' and clients' talk about interventions. Qual Health Res. 2010 Jan;20(1):29–41. doi: 10.1177/1049732309355591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ballweg M.L. Endometriosis: the complete reference for taking charge of your health. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whelan E. “No one agrees except for those of us who have it”: endometriosis patients as an epistemological community. Sociol Health Illness. 2007 Nov;29(7):957–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kjellberg S. Scholarly blogging practice as situated genre: an analytical framework based on genre theory. Inf Res [Internet] 2009 Sep;14(3) [cited 9 Jun 2010]. < http://www.informationr.net/ir/14-3/paper410.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abrahamson J.A, Fisher K.E, Turner A.G, Durrance J.C, Turner T.C. Lay information mediary behavior uncovered: exploring how nonprofessionals seek health information for themselves and others online. J Med Libr Assoc. 2008 Oct;96(4):310–23. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.96.4.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubenstein E. Dimensions of information exchange in an online breast cancer support group. Proc Am Soc Inf Sci Technol [Internet] 2009;46(1) [cited 9 Jun 2010]. < http://www.asis.org/Conferences/AM09/open-proceedings/posters/23.xml>. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Souden M. Information work in the chronic illness experience. Proc Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. [Internet] 2008;45(1) [cited 9 Jun 2010]. < http://www.asis.org/Conferences/AM08/posters/144.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Talja S, McKenzie P.J. Editors' introduction: special issue on discursive approaches to information seeking in context. Libr Q. 2007 Apr;77(2):97–108. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuominen K, Savolainen R. A social constructionist approach to the study of information use as a discursive action. In: Vakkari P, Savolainen R, Dervin B, editors. Information seeking in context: proceedings of an international conference in information needs, seeking and use in different contexts. London, UK: Taylor Graham; 1997. pp. 81–96. p. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wetherell M, Taylor S, Yates S, editors. Discourse theory and practice: a reader. London, UK: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potter J. Representing reality: discourse, rhetoric and social construction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adelswärd V, Sachs L. The meaning of 6.8: numeracy and normality in health information talks. Soc Sci Med. 1996 Oct;43(8):1179–87. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bishop F.L, Yardley L. Constructing agency in treatment decisions: negotiating responsibility in cancer. Health. 2004 Oct;8(4):465–82. doi: 10.1177/1363459304045699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ho E.Y. “Have you seen your aura lately?” examining boundary-work in holistic health pamphlets. Qual Health Res. 2007 Jan;17(1):26–37. doi: 10.1177/1049732306296364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lumme-Sandt K, Hervonen A, Jylhä M. Interpretative repertoires of medication among the oldest-old. Soc Sci Med. 2000 Jun;50(12):1843–50. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson S, Kitzinger C. Thinking differently about thinking positive: a discursive approach to cancer patients' talk. Soc Sci Med. 2000 Mar;50(6):797–811. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dewdney P, Ross C.S. Flying a light aircraft: reference service evaluation from a user's viewpoint. RQ. 1994 Winter;34(2):217–30. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross C.S, Dewdney P. Negative closure: strategies and counter-strategies in the reference transaction. Ref User Serv Q. 1999 Win;38(2):151–63. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Talja S. Analyzing qualitative interview data: the discourse analytic method. Libr Inf Sci Res. 1999 Nov;21(4):459–77. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobs N. Information technology and interests in scholarly communication: a discourse analysis. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2001 Nov;52(13):1122–33. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Talja S. The social and discursive construction of computing skills. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2005 Jan;56(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tuominen K. ‘Whoever increases his knowledge merely increases his heartache.’ moral tensions in heart surgery patients' and their spouses' talk about information seeking. Inf Res [Internet] 2004 Oct;10(1) [cited 12 Sep 2010]. < http://www.informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper202.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savolainen R. Enthusiastic, realistic and critical: discourses of Internet use in the context of everyday life information seeking. Inf Res [Internet] 2004 Oct;10(1) [cited 12 Sep 2010]. < http://www.informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper198.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKenzie P.J. Interpretative repertoires. In: Fisher K, Erdelez S, McKechnie E.F, editors. Theories of information behavior: a researcher's guide. Medford, NJ: Information Today; 2005. pp. 221–4. p. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKenzie P.J, Stooke R.K. Who is entitled to authoritative knowledge? category entitlements of parents and professionals in the literature on children's literacy learning. In: Beyond the web: technologies, knowledge and people/Au dela du web: les technologies, la connaissance et les gens: Proceedings of the 29th Annual Conference of the Canadian Association for Information Science/L'Association canadienne des sciences de l'information, Quebec, Canada, 2001 [Internet]. Canadian Association for Information Science/L'Association canadienne des sciences de l'information [cited 12 Sep 2010]. < http://www.cais-acsi.ca/proceedings/2001/McKenzie_2001.pdf>.

- 46.Nahl D, Bilal D. Information and emotion: the emergent affective paradigm in information behavior research and theory. Medford, NJ: Information Today; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saricks J. Readers' advisory service in the public library. 3rd ed. Chicago, IL: ALA Editions; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saricks J. The readers' advisory guide to genre fiction. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: ALA Editions; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chelton M.K. A crash course in RA: common mistakes librarians make and how to avoid them. Libr J. 2003 Nov;128(18):38–9. [Google Scholar]