The authors used several different proteomic techniques to identify 676 proteins in human aqueous humor. This comprehensive list of proteins can be used to establish a foundation for protein function analysis and identification of differentially expressed markers associated with anterior segment disorders.

Abstract

Purpose.

Human aqueous humor (hAH) provides nutrition and immunity within the anterior chamber of the eye. Characterization of the protein composition of hAH will identify molecules involved in maintaining a homeostatic environment for anterior segment tissues. The present study was conducted to analyze the proteome of hAH.

Methods.

hAH samples obtained during elective cataract surgery were divided into three matched groups and immunodepleted of albumin, IgG, IgA, haploglobin, antitrypsin, and transferrin. Reduced and denatured proteins (20 μg) from each group were separated by gel electrophoresis. Thirty-three gel slices were excised from each of three gel lanes (n = 99), digested with trypsin, and subjected to nanoflow liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS). The protein component of hAH was also analyzed by antibody-based protein arrays, and selected proteins were quantified.

Results.

A total of 676 proteins were identified in hAH. Of the 355 proteins identified by nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS, 206 were found in all three groups. Most of the proteins identified by nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS had catalytic, enzymatic, and structural properties. Using antibody-based protein arrays, 328 cytokines, chemokines, and receptors were identified. Most of the quantified proteins had concentrations that ranged between 0.1 and 2.5 ng/mL. Ten proteins were identified by both nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS and antibody protein arrays.

Conclusions.

Proteomic analysis of hAH identified 676 nonredundant proteins. More than 80% of these proteins are novel identifications. The elucidation of the aqueous proteome will establish a foundation for protein function analysis and identification of differentially expressed markers associated with diseases of the anterior segment.

Human aqueous humor (hAH) is a complex mixture of electrolytes, organic solutes, growth factors, cytokines, and additional proteins that provide the metabolic requirements to the avascular tissues of the anterior segment.1–5 It is produced from the nonpigmented ciliary body epithelium through active transport of ions and solutes and secreted into the posterior chamber.1,6,7 From the posterior chamber, aqueous flows between the lens and iris into the anterior chamber. hAH exits the anterior chamber via the trabecular meshwork/Schlemm's canal (conventional outflow pathway) and through the ciliary muscle bundles into the supraciliary and suprachoroidal spaces (uveoscleral pathway). A balance between the production and the drainage of hAH is important for maintaining the normal physiological intraocular pressure that is essential to maintaining the optical and refractive properties of the eye.8

The protein component of hAH is minimal, containing between 120 and 500 ng/μL of protein.9,10 The proteins in hAH are thought to arise from plasma as the result of filtration through fenestrated capillaries of the ciliary body stroma via the iris root.3 However, hAH is not a simple diffusate of plasma, since it has both qualitative and quantitative differences in protein and ion content in comparison with plasma.9–11 Furthermore, proteins in hAH that are secreted from the anterior segment tissues may have a significant role in the pathogenesis of various eye diseases.12 Several reports have indicated that changes in hAH proteomics can correlate with the prognosis of eye disorders.13–15

Identifying the protein component of tissues or fluids is vital to understanding the role these proteins have in normal physiology. Proteomic approaches have been used to identify proteins in plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and vitreous.16–21 An exhaustive database search and review of the protein component of plasma identified 1175 nonredundant proteins,22 and the Human Proteome Organization (HUPO) plasma proteome project database (http://www.bioinformatics.med.umich.edu/hupo/ppp/ provided in the public domain by the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI) contains more than 3000 proteins and protein isoforms.23 In comparison, literature searches identified less than 150 proteins in hAH. Many of these proteins were identified as individual proteins based on targeted molecules of interest by Western blot analysis or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Others were identified using proteomic approaches such as Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT)24 and differential protein expression.25 Other studies using one- and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis coupled with mass spectrometry have relied mostly on comparative studies (between control and disease eyes).25–27 Studies on rabbit aqueous humor identified 98 proteins,28 but extrapolation to hAH is difficult due to species variation. A large variation in protein identification exists in the various studies, and only a few of the proteins have been confirmed across studies. Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that little is known about the protein composition of hAH.

Characterization of the hAH proteome will provide new insights into the factors involved in maintaining anterior segment homeostasis and will also establish a foundation for biomarker discovery in various eye diseases of the anterior segment, such as glaucoma and corneal dystrophies. In the present study, we undertook a comprehensive nanoflow liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS) and antibody-based protein array approach to identifying moderate to low abundance proteins in hAH.

Methods

Collection of Human Aqueous Humor

The protocol for collection of hAH was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki. hAH was collected from patients undergoing elective cataract surgery, as previously described.29,30 Briefly, a 30-gauge needle was inserted into the midanterior chamber through a paracentesis tract. hAH was slowly aspirated until the anterior chamber began to shallow. The sample was immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C before screening. Patients had no other eye abnormalities except for the cataracts. A Bradford protein assay was performed on each hAH sample. A total of 155 hAH samples, each having a total protein concentration within the normal range (100–500 ng/μL),9,10 were used in this study.

Immunodepletion and Electrophoresis

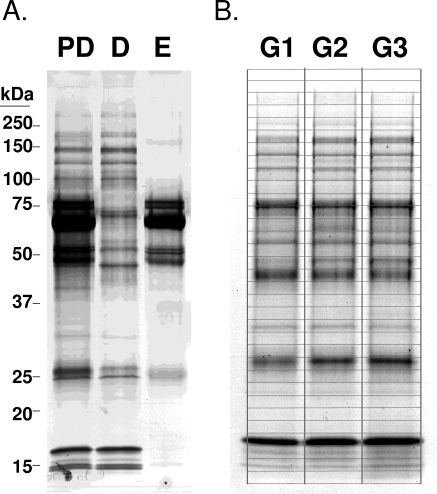

To ensure adequate volume and protein concentration for proteome analysis, 85 hAH samples were divided into three groups. Each group contained hAH acquired from individuals with similar age, sex, and protein concentrations (Table 1). Because hAH contains several abundant proteins that have been identified, an immunodepletion was performed to ensure identification of less abundant proteins. Each of the three hAH groups were run individually over a 4.6 × 50-mm commercially available protein removal system (MARS6 Multiple Affinity Removal System column; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) and immunodepleted of albumin, transferrin, antitrypsin, haploglobin, IgG, and IgA. The nonbound flow-through fraction (depleted fraction) was collected, buffer exchanged into 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate, and assayed for protein concentration. An equivalent volume of 20 μg for each sample was concentrated to dryness in a centrifugal vacuum system. Each sample was reconstituted in SDS-PAGE sample buffer with 5% β-mercaptoethanol and electrophoresed on a 10% to 14.5% SDS-PAGE precast gel (Criterion; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The gel was fixed and stained with colloidal Coomassie stain (BioSafe; Bio-Rad). Thirty-three gel slices were excised from each lane (for each group) and processed for nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Summary of Human Aqueous Humor Samples

| Sample Size (n) | Age (Mean ± SD) | Sex (M/F) | Protein Conc. (μg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectometry | ||||

| Group 1 | 30 | 72.7 ± 9.9 | 15/15 | 0.22 |

| Group 2 | 30 | 72.2 ± 9.7 | 14/16 | 0.20 |

| Group 3 | 25 | 72.7 ± 9.9 | 10/15 | 0.20 |

| Protein array | ||||

| L-series 507 | ||||

| Group 4 | 5 | 72.4 ± 9.0 | 3/2 | 0.21 |

| Group 5 | 5 | 67.8 ± 8.7 | 3/2 | 0.20 |

| Group 6 | 5 | 75.4 ± 7.2 | 2/3 | 0.16 |

| Group 7 | 6 | 69.7 ± 12.5 | 2/4 | 0.17 |

| Chemokine array | ||||

| Sample 1 | 1 | 74 | 1/0 | 0.21 |

| Sample 2 | 1 | 76 | 1/0 | 0.19 |

| Sample 3 | 1 | 89 | 1/0 | 0.40 |

| Sample 4 | 1 | 76 | 0/1 | 0.23 |

| Sample 5 | 1 | 68 | 0/1 | 0.45 |

| Sample 6 | 1 | 70 | 0/1 | 0.11 |

| Sample 7 | 3 | 80.7 ± 2.1 | 3/0 | 0.20 |

| Sample 8 | 3 | 71.3 ± 5.9 | 0/3 | 0.19 |

| Sample 9 | 5 | 73.2 ± 1.8 | 5/0 | 0.20 |

| Sample 10 | 6 | 74.5 ± 8.4 | 0/6 | 0.22 |

| Western Blot | ||||

| Sample 11 | 11 | 76.4 ± 7.3 | 2/9 | 0.28 |

| ELISA | ||||

| Sample 12 | 1 | 87 | 0/1 | 0.21 |

| Sample 13 | 1 | 71 | 1/0 | 0.19 |

| Sample 14 | 1 | 71 | 1/0 | 0.18 |

| Sample 15 | 1 | 86 | 0/1 | 0.12 |

| Sample 16 | 1 | 66 | 0/1 | 0.22 |

| Sample 17 | 1 | 60 | 0/1 | 0.19 |

| Sample 18 | 1 | 76 | 0/1 | 0.14 |

| Sample 19 | 1 | 72 | 1/0 | 0.40 |

| Sample 20 | 1 | 84 | 1/0 | 0.30 |

| Sample 21 | 1 | 78 | 0/1 | 0.10 |

| Sample 22 | 1 | 79 | 1/0 | 0.24 |

| Sample 23 | 1 | 52 | 0/1 | 0.13 |

| Sample 24 | 1 | 81 | 1/0 | 0.13 |

| Sample 25 | 1 | 91 | 0/1 | 0.48 |

| Sample 26 | 1 | 78 | 0/1 | 0.34 |

Figure 1.

Immunodepletion of hAH. (A) Eighty-five hAH samples were divided into three groups and immunodepleted of albumin, transferrin, antitrypsin, haploglobin, IgG, and IgA. Groups were separated on 10% to 14.5% SDS-PAGE gradient gels. PD, predepletion; D, immunodepleted (flow-thru); E, eluted from column. (B) Thirty-three gel slices were isolated from each group, independently trypsinized, and processed for nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS. G1, group 1; G2, group 2: G3, group 3.

Nanoflow Liquid Chromatography Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry

The 99 gel slices obtained from the three SDS-PAGE gel lanes were subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion, and the extracted peptides analyzed by nano-ESI-LC/MS/MS with a mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan LTQ Orbitrap Hybrid; ThermoElectron, Bremen, Germany) coupled to a nano-LC-2D HPLC system (Eksigent, Dublin, CA). The mass spectrometer experiment was set to perform an FT full scan from 375 to 1600 m/z, with resolution set at 60,000 (at 400 m/z), followed by linear ion trap MS/MS scans on the top five [M+2H]2+ or [M+3H]3+ ions. All MS/MS spectra were analyzed by using Mascot (version 2.2.04; Matrix Science, London, UK;), Sequest (ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, CA; version 27, rev. 12), and X! Tandem (www.thegpm.org; version 2006.09.15.3/ provided in the public domain by the Global Proteome Machine Organization, Manitoba Centre for Proteomics and Systems Biology, Winnipeg, MB, Canada). Each was set up to search the most current SwissProt database, assuming semitrypsin or full trypsin digestion with a fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.80 Da and a parent ion tolerance of 10.0 PPM (SwissProt is provided in the public domain by the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Geneva, Switzerland, http://www.expasy.ch/sprot/). Oxidation of methionine and iodoacetamide derivatives of cysteine was specified as variable modifications. Proteomics software (Scaffold, ver. 2.00.02; Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR) was used to validate MS/MS-based peptide and protein identifications. Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at a higher than 95.0% probability, as specified by the peptide prophet algorithm.31 Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at a higher than 95% probability and contain at least two unique peptides. Protein probabilities were assigned by the protein prophet algorithm.32 Proteins that contained similar peptides and could not be differentiated based on MS/MS analysis alone were grouped to satisfy the principles of parsimony.

Western Blot

hAH (300 μL) was mixed in Laemmli buffer, boiled, and separated on 4% to 15% SDS-PAGE preparative gradient gels (Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene diflouride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA) in 1× transfer buffer (50 mM Tris, 384 mM glycine, 0.01% SDS, 20% methanol). Membranes were blocked in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween, and 2% evaporated milk. Blots were probed with BigH3 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and fibulin-3 (Chemicon International, Billerica, MA) monoclonal antibodies and with myocilin polyclonal antibody (developed in our laboratory),33 followed by a secondary horseradish-peroxidase–linked anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibody (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) using a multiscreen apparatus (Bio-Rad). Antibody–antigen complexes were detected using ECL Western blot signal detection reagent (GE Healthcare). Autoradiograph film (BioMax XAR; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) was used to visualize the protein signals. Each film was digitized with a photo scanner (Perfection 2400; Epson, Long Beach, CA).

Protein Array

hAH from 21 individuals were divided into four groups, with each group having a similar age, sex, and protein concentration distribution (groups 4–7; Table 1). Each of the groups was assayed using four independent biotin label-based arrays (RayBiotech, Inc., Norcross, GA). Briefly, the four groups of hAH were independently dialyzed and the primary amine of the proteins in the sample was biotinylated, followed by dialysis to remove free biotin. The biotinylated samples were added to four different protein array slides (one sample group for each slide), which were prespotted in triplicate with antibodies for 507 different growth factors, cytokines and receptors. After incubation with Cy3-streptavidin, the signals were visualized by fluorescence. An internal control was included to monitor the function of the array process. Total signal strength was based on the average of the three spots. Proteins that had signal strength of more than threefold over the negative control (95% confidence) were considered positive.

Human Chemokine Array

Quantification of several proteins identified by the antibody-based protein array was performed (Quantikine Human Chemokine Array 1; RayBiotech). Using a glass chip–based multiplex sandwich ELISA system, we quantified proteins in 10 independent hAH samples (Table 1). Briefly, 100 μL of sample diluent was added to each well of a 16-well gasket that was fitted onto a glass slide. After an initial 30-minute incubation, 50 μL of sample was added to the well and left on a rotator for 1 hour at room temperature. After incubation, the samples were decanted from the wells and rinsed with wash buffer (supplied with the kit). Cy3-equivalent dye-conjugated streptavidin was added to each well and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. The wells were washed, and signal intensity was captured with a laser microarray scanner (GenePix 4000B; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at excitation 555 nm, emission 565 nm, and resolution 10 μm. The fluorescence intensity from the array dots corresponded to the concentration of the respective cytokine in the sample. Absolute quantification of the cytokines was calculated (RayBio Q Analyzer software ver. 5.40; RayBiotech, Inc.). Concentration of protein was established after analysis of a serial diluted five-point standard curve for each cytokine.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

A sandwich ELISA kit was used to quantify eotaxin-2 in 15 hAH samples (Table 1, samples 11–25; RayBio Human Eotaxin-2; RayBiotech, Inc.). Briefly, 50 μL of hAH was mixed with 50 μL sample dilution buffer, incubated for 2.5 hours in a microtiter plate, rinsed with wash buffer (four times), and incubated with 100 μL of biotinylated antibody for 1 hour. The solution was discarded, rinsed, incubated with 100 μL of streptavidin for 45 minutes, rinsed again, and incubated with 100 μL of substrate reagent (TMB One-Step; DakoUSA, Carpinteria, CA) for 30 minutes and read at 450 nm on a microplate reader (Infinite M200; Tecan Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA). The final concentration of eotaxin-2, expressed in pg/mL was determined by using the intersect of the standard curve prepared by assaying known concentrations of recombinant eotaxin-2.

Results

Analysis of Aqueous Humor Proteome by Nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS

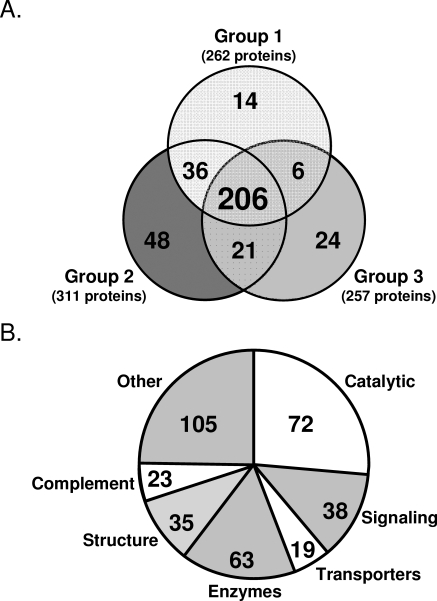

Abundant proteins, such as albumin which constitutes nearly 50% of the protein composition of hAH, tend to diminish the characterization of less abundant proteins. To remove abundant proteins and facilitate identification of intermediately expressed proteins, we immunodepleted groups 1 to 3 of hAH (Table 1) of albumin, transferrin, antitrypsin, haploglobin, fibrinogen, IgG, and IgA and separated them by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1). By means of gel slice extraction and trypsin digestion, nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS identified 355 proteins, of which 206 were in all three groups (Fig. 2A, Table 2). An additional 63 proteins were identified in two of the three groups, whereas another 86 were found in only one of the three groups (Table 2). Most the nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS identified proteins could be classified as having structural, enzymatic or catalytic properties (Fig. 2B). More than than 80% of the 355 proteins identified by nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS have not been reported in hAH. Comparison of our hAH protein dataset with two independent plasma proteome databases22,23 showed that only 58% of the hAH proteins have also been identified in human plasma.

Figure 2.

The number of hAH proteins identified by nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS. (A) The Venn diagram showing proteins that are common and unique between groups 1, 2, and 3. (B) Distribution by function of all 355 proteins identified by nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS.

Table 2.

Aqueous Humor Proteins Identified by Nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS

| Found in 3 of 3 Groups | ||

|---|---|---|

| Acid ceramidase (Q13510) | Collagen alpha-1(VI) chain (P12109) | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (P04406) |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 1 (P60709) | Collagen alpha-2(IX) chain (Q14055) | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 13 (P48723) |

| Afamin (P43652) | Complement C1r subcomponent (P00736) | Hemoglobin alpha chain (P69905) |

| Agrin (O00468) | Complement C1s subcomponent (P09871) | Hemoglobin beta chain (P68871) |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase (P30838) | Complement C2 (P06681) | Hemoglobin delta chain (P02042) |

| Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 1 (P02763) | Complement C3 (P01024) | Hemopexin (P02790) |

| Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 2 (P19652) | Complement C5 (P01031) | Heparin cofactor 2 (P05546) |

| Alpha-1-antichymotrypsin (P01011) | Complement component C6 (P13671) | Hevin (Q14515) |

| Alpha-1B-glycoprotein (P04217) | Complement component C7 (P10643) | Hexosaminidase B (P07686) |

| Alpha-2-plasmin inhibitor (P08697) | Complement component C8 α (P07357) | Histidine-proline-rich glycoprotein (P04196) |

| Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein (P02765) | Complement component C8 β (P07358) | Hyaluronan-binding protein 2 (Q14520) |

| Alpha-2-macroglobulin (P01023) | Complement component C8 γ (P07360) | Ig gamma-1 chain C region (P01857) |

| Alpha-enolase (P06733) | Complement component C9 γ (P02748) | Ins (1,3,4,5)P(4) 3-phosphate (Q9UNW1) |

| Alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase (P54802) | Complement factor B (P00751) | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 6 (P24592) |

| Amyloid beta A4 (P05067) | Complement factor H (P08603) | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (Q16270) |

| Amyloid-like 2 (Q06481) | Complement factor I (P05156) | Insulin-like growth factor-binding, acid labile (P35858) |

| Angiotensinogen (P01019) | Connective tissue growth factor (P29279) | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H1 (P19827) |

| Antithrombin-III (P01008) | Contactin-1 (Q12860) | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 (Q14624) |

| Apolipoprotein A-I (P02647) | Contactin-2 (Q02246) | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H2 (P19823) |

| Apolipoprotein A-II (P02652) | Corticosteroid-binding globulin (P08185) | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H3 (Q06033) |

| Apolipoprotein A-IV (P06727) | Cystatin A (P01040) | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor light chain (P02760) |

| Apolipoprotein D (P05090) | Cystatin C (P01034) | Interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (P10745) |

| Apolipoprotein E (P02649) | Decorin (P07585) | Kallistatin (P29622) |

| Apolipoprotein H (P02749) | Dermcidin (P81605) | Kininogen-1 (P01042) |

| Attractin (O75882) | Dickkopf-related 3 (Q9UBP4) | Latent-TGF beta-binding 2 (Q14767) |

| Autotaxin (Q13822) | Dipeptidyl-peptidase 2 (Q9UHL4) | Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein (P02750) |

| Beta crystallin B2 (P43320) | Dystroglycan (Q14118) | Limbic system-associated membrane (Q13449) |

| Beta crystallin S (P22914) | EGF-like domain-containing protein 4 (Q7Z7M0) | Lipocalin-1 (P31025) |

| Beta-2-microglobulin (P61769) | Epididymal secretory protein E1 (P61916) | Lipocalin-2 (P80188) |

| Beta-Ala-His dipeptidase (Q96KN2) | Extracellular matrix protein 1 (Q16610) | L-lactate dehydrogenase A chain (P00338) |

| Biotinidase (P43251) | Extracellular superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] (P08294) | L-lactate dehydrogenase B chain (P07195) |

| Calgranulin-A (P05109) | Ferritin heavy chain (P02794) | Lumican (P51884) |

| Calsyntenin-1 (O94985) | Ferroxidase (P00450) | Malate dehydrogenase, cytoplasmic (P40925) |

| Carbonic anhydrase 1 (P00915) | Fetuin-B (Q9UGM5) | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 (P08253) |

| Carbonic anhydrase 2 (P00918) | Fibrillin-1 (P35555) | Megalin (P98164) |

| Carbonic anhydrase-related 10 (Q9NS85) | Fibrinogen alpha chain (P02671) | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 (P01033) |

| Carboxypeptidase B2 (Q96IY4) | Fibrinogen beta chain (P02675) | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 2 (P16035) |

| Carboxypeptidase E (P16870) | Fibrinogen gamma chain (P02679) | Monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 (P08571) |

| Cartilage acidic 1 (Q9NQ79) | Fibronectin precursor (P02751) | N(4)-(beta-N-acetylglucosaminyl)-L-asparaginase (P20933) |

| Catalase (P04040) | Fibulin-1 (P23142) | N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfatase (P15586) |

| Cathepsin B (P07858) | Fibulin-3 (Q12805) | N-acetyllactosaminide β-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (O43505) |

| Cathepsin D (P07339) | Follistatin-like 5 (Q8N475) | N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase (Q96PD5) |

| Cathepsin L (P07711) | Galectin-3-binding protein (Q08380) | Neural cell adhesion molecule 1, 140 kDa (P13591) |

| Cathepsin Z (Q9UBR2) | Gamma crystallin D (P07320) | Neural cell adhesion molecule L1-like protein (O00533) |

| CD59 glycoprotein (P13987) | Gamma-Glu-X carboxypeptidase (Q92820) | Neurexin-3-alpha (Q9Y4C0) |

| Ceroid-lipofuscinosis neuronal 5(O75503) | Gelsolin (P06396) | Neuronal cell adhesion molecule (Q92823) |

| Chitinase-3-like 1 (P36222) | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (P06744) | Neuronal growth regulator 1 (Q7Z3B1) |

| Clusterin (P10909) | Glutaminyl-peptide cyclotransferase (Q16769) | Neuroserpin (Q99574) |

| Coagulation factor V (P12259) | Glutathione peroxidase 3 (P22352) | Neurotrimin (Q9P121) |

| Coagulation factor II (P00734) | Glutathione S-transferase P (P09211) | Nucleobindin-1 (Q02818) |

| Opticin (Oculoglycan) (Q9UBM4) | Protein-tyrosine-protein phosphatase zeta (P23471) | Target of Nesh-SH3 (Q7Z7G0) |

| Osteopontin (P10451) | Reelin (P78509) | Tenascin-R (Q92752) |

| Pappalysin-2 (Q9BXP8) | Retinal dehydrogenase 1 (P00352) | Testican-1 (Q08629 |

| PEBP family protein (Q96S96) | Retinoic acid receptor responder 2 (Q99969) | Testican-2 (Q92563) |

| Perlecan (P98160) | Retinoschisin (O15537) | Tetranectin (P05452) |

| Peroxiredoxin-2 (P32119) | RNase A (P07998) | Thyroxine-binding globulin (P05543) |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding 1 (P30086) | Ribonuclease T2 (O00584) | Transforming growth factor-β-induced ig-h3 (Q15582) |

| Pigment epithelium-derived factor (P36955) | Secreted frizzled-related 3 (Q92765) | Transketolase (P29401) |

| Plasma protease C1 inhibitor (P05155) | Selenium-binding 1 (Q13228) | Transthyretin (P02766) |

| Plasma retinol-binding (P02753) | Selenoprotein P (P49908) | Triosephosphate isomerase (P60174) |

| Plasma serine protease inhibitor (P05154) | Semaphorin-4B (Q9NPR2) | Tripeptidyl-peptidase 1 (O14773) |

| Plasminogen (P00747) | Semaphorin-7A (O75326) | Ubiquitin (P62988) |

| Proactivator polypeptide (P07602) | Serum albumin (P02768) | Vasorin (Q6EMK4) |

| Procollagen C-proteinase enhancer 1 (Q15113) | Serum paraoxonase/arylesterase 1 (P27169) | Vesicular integral-membrane VIP36 (Q12907) |

| Prolactin-inducible (P12273) | Sialate O-acetylesterase (Q9HAT2) | Vitamin D-binding (P02774) |

| Prostaglandin-D2 synthase (P41222) | SPARC (P09486) | Vitamin K-dependent S (P07225) |

| Protein CutA (O60888) | Spondin-1 (Q9HCB6) | Vitronectin (P04004) |

| Protein FAM3C (Q92520) | Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] (P00441) | Zinc-alpha-2-glycoprotein (P25311) |

| Protein kinase C-binding NELL2 (Q99435) | ||

| Found in 2 of 3 Groups | ||

|---|---|---|

| 14–3-3 protein zeta/delta (P63104) | Ferritin light chain (P02792) | Macrophage stimulatory protein (P26927) |

| Alpha-1-antitrypsin (P01009) | Follistatin-related protein 1 (Q12841) | Major prion protein (P04156) |

| Alpha-L-fucosidase 2 (Q9BTY2) | Gamma crystallin C (P07315) | Mammalian ependymin-related protein 1 (Q9UM22) |

| Amyloid-like 1 (P51693) | Gamma-enolase (P09104) | Mannosyl-oligosaccharide 1,2-alpha-mannosidase IA (P33908) |

| Angiogenin (P03950) | Growth-arrest-specific protein 6 (Q14393) | N-cadherin (P19022) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, cytoplasmic (P17174) | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1 (P08107) | Neurexin-2-alpha (Q9P2S2) |

| Beta-1,4-galactosyltransferase 1 (P15291) | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1L (P34931) | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase A (P15531) |

| Beta-mannosidase (O00462) | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 8 (P11142) | Peptidyl-glycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase (P19021) |

| Calcyclin (P06703) | Hornerin (Q86YZ3) | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A (P62937) |

| Calgranulin-B (P06702) | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (P00492) | Protein C7orf24 (O75223) |

| Calreticulin (P27797) | Iduronate 2-sulfatase (P22304) | Seizure 6-like protein (Q9BYH1) |

| Calsyntenin-3 (Q9BQT9) | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2 (P18065) | Semaphorin-3A (Q14563) |

| Coagulation factor X (P00742) | Interleukin-6 receptor beta chain (P40189) | Serum amyloid P-component (P02743) |

| Complement C1q TNF-related 3 (Q9BXJ4) | Kininogenin (P03952) | Sex hormone-binding globulin (P04278) |

| Complement C4-A (P0C0L4) | Lactotransferrin (P02788) | Soluble calcium-activated nucleotidase 1 (Q8WVQ1) |

| Complement factor H-related 1 (Q03591) | Leukocyte elastase inhibitor (P30740) | Stromal cell-derived factor 4 (Q9BRK5) |

| C-reactive protein (P02741) | Lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 2 (P13473) | Transaldolase (P37837) |

| Delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (P13716) | Lysozyme C (P61626) | Transferrin (P02787) |

| Dermatopontin (Q07507) | Lysyl hydroxylase 1 (Q02809) | TGF-beta-2 (P61812) |

| Desmocollin-1 (Q08554) | Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (P07333) | VPS10 domain-containing receptor SorCS1 (Q8WY21) |

| Di-N-acetylchitobiase (Q01459) | Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (P14174) | Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (Q9Y5W5) |

| Found in 1 of 3 Groups | ||

|---|---|---|

| 14–3-3 protein epsilon (P62258) | Complement C4-B (P0C0L5) | Leucine-rich repeat-containing 4B (Q9NT99) |

| 14–3-3 protein sigma (P31947) | Complement factor D (P00746) | Lipophilin-B (O95969) |

| 40S ribosomal protein S5 (P46782) | Complement factor H-related 2 (P36980) | Microfibril-associated glycoprotein 4 (P55083) |

| 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating (P52209) | Cystatin S (P01036) | Neogenin (Q92859) |

| Adipocyte-derived leucine aminopeptidase (Q9NZ08) | Desmocollin-3 (Q14574) | Neutrophil defensin 1 (P59665) |

| Aldose reductase (P15121) | Desmoglein-2 (Q14126) | Nidogen-1 (P14543) |

| Alpha-mannosidase 2 (Q16706) | Desmoplakin (P15924) | Peroxiredoxin-1 (Q06830) |

| Alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminidase (P17050) | Desmoplakin-3 (P14923) | Peroxiredoxin-6 (P30041) |

| Angiopoietin-like 7 factor (O43827) | Elongation factor 1-alpha 1 (P68104) | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 (P18669) |

| Annexin A1 (P04083) | Elongation factor 2 (P13639) | Plexin-B2 (O15031) |

| Annexin A2 (P07355) | Fatty acid-binding protein, epidermal (Q01469) | Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2 (Q10471) |

| Annexin A5 (P08758) | Fibroblast growth factor-binding 2 (Q98YJ0) | Proteasome subunit alpha type 5 (P28066) |

| Apolipoprotein B-100 (P04114) | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A (P04075) | Protein S100-A7 (P31151) |

| Arginase-1 (P05089) | Galectin-7 (P47929) | Protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor (Q9UK55) |

| ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial (P06576) | Ganglioside GM2 activator (P17900) | Protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase E (Q08188) |

| Beta crystallin B1 (P53674) | Glucosidase 2 subunit beta (P14314) | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase (P00491) |

| Beta-hexosaminidase alpha chain (P06865) | Glutamate receptor 4 (P48058) | Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 (P14618) |

| Cadherin-6 (P55285) | Glutathione reductase, mitochondrial (P00390) | Retinoic acid receptor responder 1 (P49788) |

| Calsyntenin-2 (Q9H4D0) | Glutathione synthetase (P48637) | Salivary alpha-amylase (P04745) |

| Carbonic anhydrase 3 (P07451) | Glutathione transferase omega-1 (P78417) | S-arrestin (P10523) |

| Carboxypeptidase A4 (Q9UI42) | Hemoglobin subunit gamma-1 (P69891) | Secretogranin-1 (P05060) |

| Caspase-14 (P31944) | Hepatocyte growth factor activator (Q04756) | Serpin B12 (Q96P63) |

| CD44 antigen (P16070) | Ig gamma-2 chain C region (P01859) | Serpin B3 (P29508) |

| CD98 antigen (P08195) | Ig gamma-4 chain C region (P01861) | Serpin B6 (P35237) |

| Coagulation factor XII (P00748) | Ig kappa chain C region (P01834) | Serum amyloid A-4 (P35542) |

| Collagen alpha-3(VI) chain (P12111) | Insulin-like growth factor-binding 4 (P22692) | Thrombospondin-4 (P35443) |

| Complement C1q subcomponent subunit A (P02745) | Insulin-like growth factor-binding 5 (P24593) | Tropomyosin alpha-3 chain (P06753) |

| Complement C1q subcomponent subunit B (P02746) | Kallikrein-11 (Q9UBX7) | Vacuolar ATP synthase subunit S1 (Q15904) |

| Complement C1q subcomponent subunit C (P02747) | Keratocan (O60938) | |

The UniProt accession number is shown in parentheses for each protein (UniProt is provided in the public domain by The UniProt Consortium; http://www.uniprot.org).

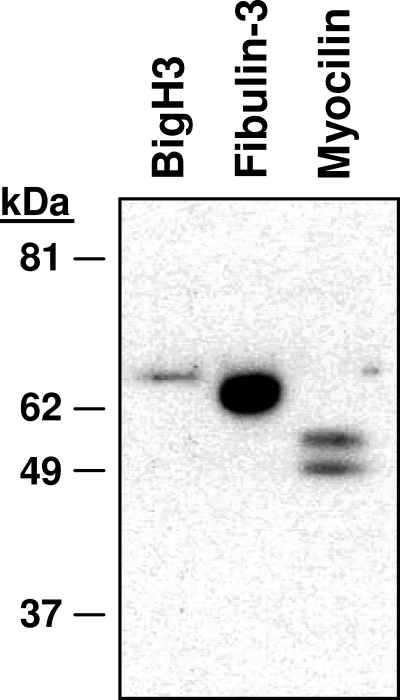

To verify our mass spectrometry results, we analyzed two random proteins, BigH3 (kerato-epithelin) and fibulin-3, by Western blot for their presence in an independent hAH sample (Table 1). Antibodies against both proteins confirmed the presence of BigH3 and fibulin-3 in hAH (Fig. 3). A third protein, myocilin, which has been reported in hAH34,35 and confirmed by our nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS study, was also identified in hAH by Western blot (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Verification of BigH3, fibulin-3, and myocilin in hAH. Three proteins—BigH3, fibulin-3, and myocilin—were assessed by Western blot for their presence in hAH. All three proteins were determined to be present in the three groups by nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS and were confirmed by Western blot analysis.

Growth Factor, Cytokine, and Receptor Identification in Aqueous Humor

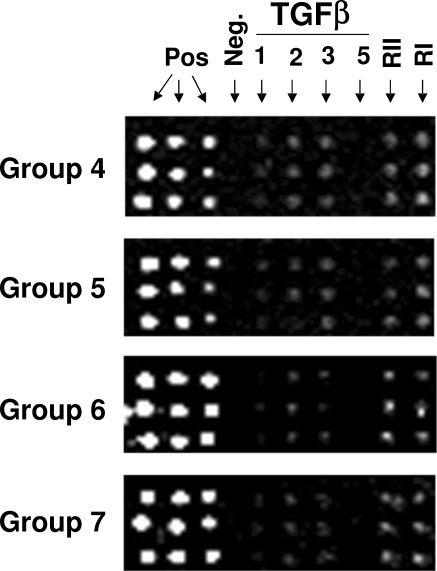

Of the 355 proteins identified by mass spectrometry, only a small percentage of the proteins were growth factors, cytokines, or receptors, which is not surprising considering their relative low abundance. We implemented a more targeted approach to identify growth factors, cytokines, and receptors in hAH, where 21 hAH samples were divided into four groups (groups 4–7, Table 1) and used to independently probe antibody-based protein arrays (RayBiotech). Of the 507 proteins on the arrays, 328 were identified in hAH. A total of 217 proteins were identified in at least three of four groups, whereas another 111 proteins were found in only one or two groups (Table 3). An illustration of the results for some of the TGFβ family members is shown in Figure 4. TGFβ2 and -3 and TGFβ type I and II receptors were identified in all four groups. TGFβ1 was identified in two groups (groups 4 and 5) and TGFβ5 was not present in any of the four groups. Only 10 proteins identified by the antibody-based protein array were also detected in nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS studies.

Table 3.

Growth Factors, Cytokines, and Receptors in Aqueous Humor

| In 4 of 4 Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activin RIA/ALK-2 | CXCL11 | GASP-1/WFIKKNRP | Leptin (OB) | Osteocrin |

| Activin RIB/ALK-4 | CXCL13 | G-CSF R/CD 114 | LIF R alpha | OX40 ligand/TNFSF4 |

| Angiopoietin-2 | CXCL14/BRAK | GFR alpha-2 | LIGHT/TNFSF14 | PD-ECGF |

| Angiopoietin-4 | CXCR2/IL-8 RB | GFR alpha-3 | Lipocalin-1 | PF4/CXCL4 |

| Angiopoietin-like 1 | CXCR3 | GFR alpha-4 | L-Selectin (CD62L) | Pref-1 |

| APRIL | CXCR4 (fusin) | Glucagon | Luciferase | RELM beta |

| AR (Amphiregulin) | CXCR5/BLR-1 | Glut1 | Lymphotoxin beta R | S100 A8/A9 |

| Artemin | DcR3/TNFRSF6B | Glut3 | MCP-1 | Smad 8 |

| Axl | Dkk-3 | Glut5 | MCP-2 | Soggy-1 |

| B7-1/CD80 | Dkk-4 | Glypican 3 | M-CSF | SPARC |

| BD-1 | DR3/TNFRSF25 | ICAM-2 | M-CSF R | Spinesin |

| beta-NGF | Dtk | IFN-alpha/beta R1 | MFG-E8 | TACI/TNFRSF13B |

| BMP-5 | EGF | IFN-gamma R1 | MFRP | TCCR/WSX-1 |

| BMPR-IA/ALK-3 | Epiregulin | IGFBP-1 | MIF | TGF-beta 2 |

| CCL28/VIC | ErbB3 | IGFBP-2 | MIP-1b | TGF-beta 3 |

| CCR1 | Fas Ligand | IGFBP-3 | MMP-10 | TGF-beta RI/ALK-5 |

| CCR2 | FGF Basic | IL-1 R9 | MMP-11/Stromelysin-3 | TGF-beta RII |

| CCR3 | FGF R3 | IL-12 p70 | MMP-13 | Thrombospondin-1 |

| CCR4 | FGF R4 | IL-12 R beta 1 | MMP-15 | Thrombospondin-2 |

| CCR7 | FGF-11 | IL-17E | MMP-24/MT5-MMP | TLR1 |

| CCR8 | FGF-18 | IL-21 R | MMP-7 | TLR4 |

| CCR9 | FGF-4 | IL-23 | MMP-8 | TRAIL R4/TNFRSF10D |

| CD14 | FGF-5 | IL-23 R | MMP-9 | TREM-1 |

| CD117 | FGF-9 | IL-3 R alpha | NAP-2 | TROY/TNFRSF19 |

| CD154 | FGF-BP | IL-31 | NCAM-1/CD56 | TSG-6 |

| CD163 | Follistatin | IL-31 RA | Neuropilin-2 | VCAM-1 (CD106) |

| Chordin-Like 1 | Follistatin-like 1 | IL-6 R | Neurturin | VE-Cadherin |

| Chordin-Like 2 | Fractalkine | Inhibin B | NGF R | VEGF-B |

| CLC | Frizzled-3 | Kremen-2 | NOV/CCN3 | VEGI |

| CNTF R alpha | Frizzled-4 | LBP | Orexin B | WIF-1 |

| CRTH-2 | ||||

| In 3 of 4 Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6Ckine | EDA-A2 | Glut2 | IL-20 R beta | Osteoprotegerin |

| Activin RII A/B | EDG-1 | HRG-beta 1 | IL-24 | PDGF-D |

| Adiponectin | Eotaxin/CCL11 | ICAM-1 | Inhibin A | Persephin |

| AgRP | Eotaxin-2/MPIF-2 | IGFBP-rp1/IGFBP-7 | IP-10 | PIGF |

| Angiopoietin-like factor | ErbB4 | IL-1 F7/FIL1 zeta | Kininostatin | RELT/TNFRSF19L |

| Angiostatin | Erythropoietin | IL-1 R6/IL-1 Rrp2 | Kremen-1 | SDF-1/CXCL12 |

| BCMA/TNFRSF17 | E-Selectin | IL-1 F10/IL-1HY2 | Latent TGF-beta bp1 | sFRP-1 |

| beta-Catenin | FAM3B | IL-13 R alpha 2 | Lck | Siglec-9 |

| BIK | FGF-20 | IL-17F | Lefty - A | SLPI |

| CCL14 | FGF-7/KGF | IL-17RC | LRP-6 | Thrombopoietin (TPO) |

| CCR6 | Frizzled-1 | IL-18 R beta/AcPL | Lymphotoxin beta | Thrombospondin-4 |

| Cerberus 1 | GASP-2/WFIKKN | IL-20 | MCP-4/CCL13 | TLR3 |

| Chem R23 | GCP-2/CXCL6 | IL-20 R alpha | MDC | VEGF-D |

| Decorin | ||||

| In 2 of 4 Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activin A | EDAR | GDF1 | HGFR | MMP-14 |

| Activin B | EGF R/ErbB1 | GDF3 | IGF-II | MMP-16/MT3-MMP |

| Activin C | EG-VEGF/PK1 | GDF5 | IL-1 F6/FIL1 epsilon | MSP alpha chain |

| Activin RIIA | Endoglin/CD105 | GDF8 | IL-1 F9/IL-1 H1 | MSP beta-chain |

| Angiogenin | Endostatin | GDF9 | IL-17RD | NT-4 |

| Angiopoietin-like 2 | EN-RAGE | GDF11 | IL-18 R alpha/IL-1 R5 | PLUNC |

| APJ | Eotaxin-3/CCL26 | GDF-15 | IL-8 | P-selectin |

| BDNF | Fas/TNFRSF6 | GFR alpha-1 | IL-9 | sgp130 |

| beta-Defensin 2 | FGF-12 | GITR Ligand | Insulin R | TFPI |

| BMP-2 | FGF-19 | GM-CSF | Leptin R | TGF-beta 1 |

| BMP-6 | FGF-21 | GREMLIN | LIF | Thrombospondin |

| BMP-15 | FGF-8 | GRO-a | Lymphotactin/XCL1 | TMEFF2 |

| CTACK/CCL27 | GCSF | Hepassocin | MIP-1a | |

| In 1 of 4 Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP-7 | Galectin-3 | IL-11 | Insulin | Siglec-5/CD170 |

| BMP-8 | Granzyme A | IL-12 p40 | LRP-1 | SMDF/NRG1Isoform |

| BTC | HCR/CRAM-A/B | IL-12 R beta 2 | MAC-1 | Tissue Factor |

| CD40/TNFRSF5 | HGF | IL-17B R | MIP-3 beta | TNF-beta |

| CTLA-4/CD152 | HRG-alpha | IL-19 | MMP-3 | TRAIL R3/TNFRSF10C |

| CXCR1/IL-8 RA | IGFBP-6 | IL-2 R gamma | MMP-12 | TWEAK/TNFSF12 |

| D6 | IGF-I SR | IL-21 | Musk | Ubiquitin 1 |

| Endocan | IL-1 alpha | IL-22 BP | Neuregulin | VEGF |

| FGF-6 | IL-1 beta | IL-7 R alpha | PARC/CCL18 | VEFR R3 |

| Frizzled-7 | IL-1 ra | |||

Figure 4.

Presence and absence of several TGFβ family members in hAH. Representative images of several TGFβ-family members and their corresponding fluorescent signal intensity from antibody-based protein arrays. TGFβ2, TGFβ3, type I, and type II receptors were present in all four groups (groups 4–7). TGFβ1 was present in groups 4 and 5, but was “absent” in groups 6 and 7 because of low signal strength of less than threefold above background. TGFβ5 was negative in all groups.

Quantification of Growth Factors and Cytokines

Using independent hAH samples (Table 1, samples 1–10) and a chemokine array kit (Quantibody Human Chemokine Array 1; RayBiotech), we quantified 25 proteins (Table 4). Most of the growth factors and cytokines quantified had concentrations between 0.1 and 2.5 ng/mL. Osteopontin, a member of the matricellular protein family, originally identified in hAH by the nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS studies had exhibited levels near 70 ng/mL. Three additional proteins, IL-18 BPA, IL-28A, and IL-29, that were analyzed on the chemokine array, but were not included in the antibody-based protein array containing 507 proteins, were also identified in hAH. Six additional quantified proteins (IL-17P, MCP-3, MIP-3a, MPIF-1, TARC, and TSLP) that were not present in the antibody-based protein array were confirmed to be absent by the cytokine array. Eotaxin-2, which was not one of the cytokines spotted on the cytokine array, was assayed by ELISA (Table 1, samples 11–25). Eotaxin-2 was confirmed to be present in hAH with a concentration of 49 ± 31 pg/mL (mean ± SD, n = 15).

Table 4.

Quantification of 25 Aqueous Humor Proteins

| Protein | hAH (pg/mL) |

|---|---|

| 6Ckine | 713 ± 186 |

| CTACK | 1259 ± 330 |

| CCL28 | 220 ± 56 |

| Eotaxin-2 | 49 ± 31* |

| Eotaxin-3 | 484 ± 111 |

| GCP-2 | 129 ± 48 |

| GRO | 239 ± 52 |

| HCC-1 | 2507 ± 843 |

| IL-9 | 6881 ± 2585 |

| IL-17P | NP |

| IL-18 BPA | 689 ± 409 |

| IL-28A | 317 ± 118 |

| IL-29 | 2205 ± 672 |

| IP-10 | 225 ± 277 |

| LIF | 133 ± 59 |

| MCP-2 | 10 ± 7 |

| MCP-3 | NP |

| MDC | 24 ± 23 |

| MIP-3a | NP |

| MPIF-1 | NP |

| NAP-2 | 1261 ± 851 |

| OPN | 69813 ± 21625 |

| PARC | 1656 ± 1101 |

| TARC | NP |

| TSLP | NP |

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 10). NP, not present (below assay's sensitivity).

Analyzed by ELISA.

Discussion

Avascular tissues of the anterior chamber receive their external cues from components of aqueous humor. Changes in protein or ionic concentrations within aqueous humor may have significant effects on cellular function and cell–matrix communication. However, only approximately 150 proteins have been identified in hAH. Using an approach that included multiple proteomic techniques and multigroup comparisons, we have identified 676 nonredundant proteins in hAH. More than 80% of the proteins are novel identifications for aqueous humor. To date, this study provides the most comprehensive list of proteins present in hAH.

Aqueous humor maintains a normal homeostatic environment and is essential to the proper functioning of anterior chamber tissues. Therefore, it is not surprising that most of the proteins identified by nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS have catalytic and enzymatic functions. For example, one of the functions of aqueous humor is to maintain a pathogen-free environment. Being immunoprivileged, the anterior chamber relies on complement to successfully rid the chamber of pathogens. Our proteomic data supports the presence of both the classic and alternative complement pathways. In all, 23 complement proteins were identified in hAH including C1q, C1r, C1s, C2–9, and complement regulatory molecules such as CD59; complement B, D, H, and I; and C1 inhibitor. The balance between complement activation molecules and complement regulatory molecules is important in maintaining healthy anterior segment tissues and avoiding autoimmune reactions that would significantly alter the function of these tissues.

Catalytic proteins such as type IV collagen are principal components of basement membranes36 and are one of the major extracellular matrix proteins upregulated during glaucoma. Other catalytic enzymes found in hAH, such as lactate dehydrogenase, have already been suggested to have a role in hAH outflow regulation, while showing a strong presence in the uveoscleral tissue.37 Several respiratory pathway catalytic enzymes such as aldolase and ketolase were also found in hAH and may have been secreted into the hAH by cells bathed by the fluid. The presence of strong angiogenic inducers as angiogenin and angiogenic inhibitors PEDF,38 type IV collagen,39 and vitamin D binding protein,40 suggests the presence of an equilibrium within hAH between proangiogenic and antiangiogenic molecules. The balance between angiogenic and antiangiogenic proteins may be important in the pathogenesis of anterior segment diseases.

Our antibody-based protein array study served the purpose of identifying proteins in the hAH that are present in low abundance and therefore are difficult to identify by nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS. Several members of the transforming growth factor β, tumor necrosis factor, fibroblast growth factor, interleukin, and growth differentiation factor families were identified. In addition, numerous growth factor and cytokine receptors were found in hAH, including receptors of the C-C chemokine, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin superfamilies. In other biological fluids, circulating and soluble receptors play an important role in regulating growth factor and cytokine activity. Soluble receptors are normal components of body fluids in healthy individuals and levels of these receptors can modulate various growth factor and cytokine activities.41 For example, ligand binding to soluble receptors can protect the ligand from degradation, inhibit the ligand from initiating a signaling cascade or act in an agonistic manner. In the case of IL-6, the binding of IL-6 to its soluble receptor can stimulate cells that do not normally express an IL-6 receptor.42,43 Analysis of soluble receptors in hAH isolated from anterior chamber disorders, such as corneal dystrophies and glaucoma, may serve, not only as markers for the disease but as therapeutic targets in treating the disorder.

An important question in the midst of the description of the hAH proteome is “where are all the proteins found in hAH coming from?” Although hAH is considered to be a plasma filtrate, there are considerable differences between plasma and hAH that suggest several cells and tissues from the anterior segment may be involved in active secretion of ions/proteins into hAH.9–11 Bovine and primate studies suggest that hAH proteins originate in the ciliary body capillaries and move via a protein gradient toward the iris root where they diffuse through the ciliary epithelium into hAH.2,44,45 However, other studies have suggested that the ciliary epithelium and the pigmented and nonpigmented cells of the ciliary body are actively involved in pumping out regulatory proteins into the hAH possibly in conjunction with tissues surrounding the anterior/posterior chambers.46,47 These proteins include hemopexin, ceruloplasmin, ferroxidase, and glutathione S-transferase, enzymatic proteins involved in detoxification and oxidative damage protection.48 Although many of the proteins identified may come from blood, cDNAs encoding plasma proteins have also been identified in the ciliary body.46 Among these are complement component C4, α2-macroglobulin, and the plasma form of glutathione peroxidase.46 Our study confirmed their presence in human hAH and suggests that the ciliary body may be one of the tissues in the anterior chamber that has the ability to produce and secrete traditional plasma proteins into hAH.

hAH samples obtained from patients undergoing cataract removal has been the traditional control in studies of hAH from patients with anterior chamber disorders, such as uveal melanoma, myopia, corneal rejection, and glaucoma.25–27,49,50 Although considered normal, the presence of a cataract affects the concentration and components of hAH as suggested by the increase in α-antitrypsin, α2-macroglobulin, and β-crystallin proteins.51,52 Although hAH collected from normal healthy adults would have been ideal, such samples cannot be obtained ethically.53 Therefore, it is possible that some of the proteins identified in our study are present because of the underlying cataract condition. Another limitation of this study was that our growth factor, cytokine, and receptor analysis was limited to the proteins that were present on the protein array. Therefore, not all growth factors, cytokines, and receptors in hAH were identified. Although our study was thorough, 676 proteins are probably only a fraction of the overall protein profile within hAH. Nevertheless, our study provides a comprehensive list of the hAH proteins. This list may be considered as a reference to look for differences in protein expression in various pathologic conditions of the anterior segment with the possibility of identifying novel biomarkers for the disease and possible targets for novel therapeutic treatments.

Footnotes

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health research Grants EY07065 and EY15736; Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York; and the Mayo Foundation, Rochester, Minnesota.

Disclosure: U. Roy Chowdhury, None; B.J. Madden, None; M.C. Charlesworth, None; M.P. Fautsch, None

References

- 1. To CH, Kong CW, Chan CY, Shahidullah M, Do CW. The mechanism of aqueous humour formation. Clin Exp Optom. 2002;85:335–349 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barsotti MF, Bartels SP, Freddo TF, Kamm RD. The source of protein in the aqueous humor of the normal monkey eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:581–595 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Freddo TF, Bartels SP, Barsotti MF, Kamm RD. The source of proteins in the aqueous humor of the normal rabbit. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:125–137 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Freddo TF. The Glenn A. Fry Award Lecture 1992: aqueous humor proteins: a key for unlocking glaucoma? Optom Vis Sci. 1993;70:263–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McLaren JW, Ziai N, Brubaker RF. A simple three-compartment model of anterior segment kinetics. Exp Eye Res. 1993;56:355–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fitt AD, Gonzalez G. Fluid mechanics of the human eye: aqueous humour flow in the anterior chamber. Bull Math Biol. 2006;68:53–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murray DL, Bartels SP. The relationship between aqueous humor flow and anterior chamber protein concentration in rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:370–376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mark HH. Aqueous humor dynamics in historical perspective. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55:89–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cole DF. Comparative aspects of the intraocular fluids. In: Davson H, Graham LT., Jr eds. The Eye. New York: Academic Press; 1974:71–121 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tripathi RC, Millard CB, Tripathi BJ. Protein composition of human aqueous humor: SDS-PAGE analysis of surgical and post-mortem samples. Exp Eye Res. 1989;48:117–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kinsey VE. The chemical composition and the osmotic pressure of the aqueous humor and plasma of the rabbit. J Gen Physiol. 1951;34:389–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klenkler B, Sheardown H. Growth factors in the anterior segment: role in tissue maintenance, wound healing and ocular pathology. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:677–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fleenor DL, Shepard AR, Hellberg PE, Jacobson N, Pang IH, Clark AF. TGFbeta2-induced changes in human trabecular meshwork: implications for intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:226–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maatta M, Tervahartiala T, Harju M, Airaksinen J, Autio-Harmainen H, Sorsa T. Matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors in aqueous humor of patients with primary open-angle glaucoma, exfoliation syndrome, and exfoliation glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2005;14:64–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ozcan AA, Ozdemir N, Canataroglu A. The aqueous levels of TGF-beta2 in patients with glaucoma. Int Ophthalmol. 2004;25:19–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garcia-Ramirez M, Canals F, Hernandez C, et al. Proteomic analysis of human vitreous fluid by fluorescence-based difference gel electrophoresis (DIGE): a new strategy for identifying potential candidates in the pathogenesis of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1294–1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goldman D, Merril CR, Ebert MH. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of cerebrospinal fluid proteins. Clin Chem. 1980;26:1317–1322 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim T, Kim SJ, Kim K, et al. Profiling of vitreous proteomes from proliferative diabetic retinopathy and nondiabetic patients. Proteomics. 2007;7:4203–4215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sickmann A, Dormeyer W, Wortelkamp S, Woitalla D, Kuhn W, Meyer HE. Towards a high resolution separation of human cerebrospinal fluid. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;771:167–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yuan X, Desiderio DM. Proteomics analysis of human cerebrospinal fluid. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;815:179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yuan X, Desiderio DM. Proteomics analysis of prefractionated human lumbar cerebrospinal fluid. Proteomics. 2005;5:541–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anderson NL, Polanski M, Pieper R, et al. The human plasma proteome: a nonredundant list developed by combination of four separate sources. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:311–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Omenn GS, States DJ, Adamski MR, et al. Overview of the HUGO Plasma Proteome Project: results from the pilot phase with 35 collaborating laboritories and multiple analytical groups, generating a core dataset of 3020 proteins and a publicly-available database. Proteomics. 2005;5:3226–3245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Richardson MR, Price MO, Price FW, et al. Proteomic analysis of human aqueous humor using multidimensional protein identification technology. Mol Vis. 2009;15:2740–2750 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rohde E, Tomlinson AJ, Johnson DH, Naylor S. Comparison of protein mixtures in aqueous humor by membrane preconcentration-capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:2361–2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duan X, Lu Q, Xue P, et al. Proteomic analysis of aqueous humor from patients with myopia. Mol Vis. 2008;14:370–377 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Funding M, Vorum H, Honore B, Nexo E, Ehlers N. Proteomic analysis of aqueous humour from patients with acute corneal rejection. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005;83:31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stastna M, Behrens A, Noguera G, Herretes S, McDonnell P, Van Eyk JE. Proteomics of the aqueous humor in healthy New Zealand rabbits. Proteomics. 2007;7:4358–4375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fautsch MP, Johnson DH. Characterization of myocilin-myocilin interactions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2324–2331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fautsch MP, Vrabel AM, Peterson SL, Johnson DH. In vitro and in vivo characterization of disulfide bond use in myocilin complex formation. Mol Vis. 2004;10:417–425 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem. 2002;74:5383–5392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nesvizhskii AI, Keller A, Kolker E, Aebersold R. A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2003;75:4646–4658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fautsch MP, Bahler CK, Jewison DJ, Johnson DH. Recombinant TIGR/MYOC increases outflow resistance in the human anterior segment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:4163–4168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rao PV, Allingham RR, Epstein DL. TIGR/myocilin in human aqueous humor. Exp Eye Res. 2000;71:637–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Russell P, Tamm ER, Grehn FJ, Picht G, Johnson M. The presence and properties of myocilin in the aqueous humor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:983–986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kefalides NA. Structure and biosynthesis of basement membranes. Int Rev Connect Tissue Res. 1973;6:63–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cavallotti C, Pescosolido N, Artico M, Cavallotti D. Uveoscleral outflow in dog's eye: role of several enzymes. Int Ophthalmol. 1998;22:233–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dawson DW, Volpert OV, Gillis P, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor: a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Science. 1999;285:245–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Colorado PC, Torre A, Kamphaus G, et al. Anti-angiogenic cues from vascular basement membrane collagen. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2520–2526 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kalkunte S, Brard L, Granai CO, Swamy N. Inhibition of angiogenesis by vitamin D-binding protein: characterization of anti-endothelial activity of DBP-maf. Angiogenesis. 2005;8:349–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Heaney ML, Golde DW. Soluble receptors and human disease. J Leukocyte Biol. 1998;64:135–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mackiewicz A, Schooltink H, Heinrich PC, Rose-John S. Complex of soluble human IL-6-receptor/IL-6 up-regulates expression of acute-phase proteins. J Immunol. 1992;149:2021–2027 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Taga T, Hibi M, Hirata Y, et al. Interleukin-6 triggers the association of its receptor with a possible signal transducer, gp130. Cell. 1989;58:573–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Allansmith MR, Whitney CR, McClellan BH, Newman LP. Immunoglobulins in the human eye: location, type, and amount. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;89:36–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Radius RL, Anderson DR. Distribution of albumin in the normal monkey eye as revealed by Evans blue fluorescence microscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1980;19:238–243 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Coca-Prados M, Escribano J, Ortego J. Differential gene expression in the human ciliary epithelium. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:403–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ortego J, Escribano J, Coca-Prados M. Gene expression of proteases and protease inhibitors in the human ciliary epithelium and ODM-2 cells. Exp Eye Res. 1997;65:289–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ahmad H, Singh SV, Srivastava SK, Awasthi YC. Glutathione S-transferase of bovine iris and ciliary body: characterization of isoenzymes. Curr Eye Res. 1989;8:175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Missotten GS, Beijnen JH, Keunen JEE, Bonfrer JMG. Proteomics of uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:627–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Howell KG, Vrabel AM, Roy Chowdhury U, Stamer WD, Fautsch MF. Myocilin levels in primary open-angle glaucoma and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma human aqueous humor. J Glaucoma. Published online February 22, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nakamura M, Russell P, Carper DA, Inana G, Kinoshita JH. Alteration of a developmentally regulated, heat-stable polypeptide in the lens of the Philly mouse. Implications for cataract formation. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:19218–19221 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ando H, Twining SS, Yue BY, et al. MMPs and proteinase inhibitors in the human aqueous humor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:3541–3548 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Escoffier P, Paris L, Bodaghi B, Danis M, Mazier D, Marinach-Patrice C. Pooling aqueous humor samples: bias in 2D-LC-MS/MS strategy? J Proteome Res. 2010;9:789–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]