Abstract

Mast cells have long been recognized to have a direct and critical role in allergic and inflammatory reactions. In allergic diseases, these cells exert both local and systemic responses, including allergic rhinitis and anaphylaxis. Mast cell mediators are also related to many chronic inflammatory conditions. Besides the roles in pathological conditions, the biological functions of mast cells include roles in innate immunity, involvement in host defense mechanisms against parasites, immunomodulation of the immune system, tissue repair, and angiogenesis. Despite their growing significance in physiological and pathological conditions, much still remains to be learned about mast cell biology. This paper presents evidence that lipid rafts or raft components modulate many of the biological processes in mast cells, such as degranulation and endocytosis, play a role in mast cell development and recruitment, and contribute to the overall preservation of mast cell structure and organization.

1. Introduction

Mast cells, like blood cells, are derived from pluripotent bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells but, unlike blood cells, they leave the bone marrow as progenitors and migrate into virtually all vascularized tissues to complete their differentiation under the influence of factors present at each tissue site. It is the microenvironment surrounding the mast cells that determines their mature phenotype [1–6]. Mast cells are effector cells of allergic and anaphylactic reactions and play a role in many physiological and pathological processes [7, 8]. Recently, they have gained new importance as immunoregulatory cells with the recognition that they are a major source of cytokines and chemokines and play roles in both innate and adaptive immunities [7, 9, 10]. Although mast cells may be activated by a number of stimuli and pathways [11, 12], the major mechanism for their activation and subsequent degranulation is through the high-affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E (FcεRI), present in the plasma membrane of mast cells, epidermal Langerhans cells, eosinophils, and basophils [13]. FcεRI is expressed as a heterotetrameric structure composed of one α subunit with an extracellular domain that binds IgE, a four-transmembrane-spanning β subunit, and two identical disulphide linked γ subunits [14–17]. The β subunit serves as an important amplifier of IgE and antigen-induced signaling events. Furthermore, the γ subunits are essential for initiating signaling events downstream of FcεRI [17, 18]. The carboxyl terminal cytoplasmic domains of both the β and γ subunits contain an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM), common to all multisubunit immune recognition receptors, that is critical for cell activation. Because the receptor subunits lack any known enzymatic activity, FcεRI must rely on associated molecules for transducing intracellular signals [16, 19, 20]. Mast cell activation is initiated by the binding of oligomeric antigens to receptor-bound IgE, which crosslinks FcεRI and results in its aggregation. The first recognized biochemical event of the cytoplasmic signal transduction cascade involves phosphorylation, presumably by Lyn, of two conserved tyrosine residues within the ITAMs of both β and γ subunits of the receptor. The tyrosine-phosphorylated ITAMs create a novel binding surface that is recognized by additional cytoplasmic signaling molecules, such as the protein tyrosine kinase Syk which binds mainly to the γ subunit, via its tandem Src homology 2 (SH2) domains. This interaction results in a conformational change in Syk, followed by its activation and autophosphorylation. This results in an increased kinase activity that rapidly shifts the equilibrium of the cell from a resting state (where phosphorylation and dephosphorylation activities are approximately equal) to an activated state (where phosphorylation activity increases exponentially and cannot be counteracted by dephosphorylation). This Syk-mediated signal amplification results in a direct or indirect activation of several proteins, including linker for activation of T cells (LAT), Vav, phospholipase C-γ1 (PLC-γ1), and PLC-γ2. Finally, downstream activation results in an increase in intracellular calcium levels, activation of other enzymes and adaptors, and rearrangement of the cytoskeleton that culminates in the release of three classes of mediators: (1) preformed mediators (stored in secretory granules), such as histamine, heparin, β-hexosaminidase, neutral proteases, acid hydrolases, major basic protein, carboxypeptidases, and some cytokines and growth factors, (2) newly formed lipid mediators, such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes, and (3) newly synthesized mediators, that include growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines [14, 21, 22]. Accumulating evidence suggests that lipid rafts or raft components play a pivotal role in signal transduction via FcεRI in mast cells and that the organization of various molecules in lipid rafts could modulate many biological processes in these cells.

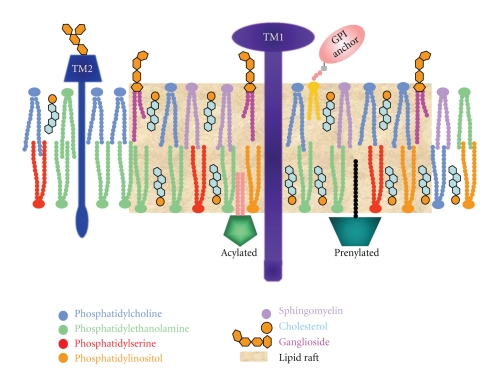

Lipid rafts, present in all eukaryotic cells, are currently defined as dynamic-ordered nanoscale assemblies of proteins and lipids of the plasma membrane and other intracellular membranes, such as Golgi membranes, that associate and dissociate on a subsecond timescale [4, 23, 24]. They contain high levels of cholesterol, sphingolipids (such as sphingomyelin), and gangliosides. Lipid rafts selectively concentrate glycosylphosphatidylinositol- (GPI-) anchored proteins on their outer side and proteins anchored by saturated palmitoyl or myristoyl groups and cholesterol-binding proteins on the cytoplasmic side [25–29]. Their lipid composition (Figure 1), with a preponderance of longer saturated hydrocarbon chains that potentiate interdigitation between leaflets [30] and favors interaction with cholesterol [31], allows cholesterol to be tightly intercalated. Lipid rafts are highly organized and probably exist in a liquid-ordered (l o) phase, different from the rest of the plasma membrane which consists mainly of phospholipids (with unsaturated tails) in a liquid-disordered (l d) phase [32]. The extent of packing depends on the degree of saturation. The cis double bond present on unsaturated lipids introduces a rigid bend in the hydrocarbon tail which interferes with the tight packing and results in less stable aggregates [33]. Lipid rafts are characterized by high melting temperature and a resistance to solubilization in nonionic detergents such as Triton X-100, at low temperature [34]. They are dynamic in that both proteins and lipids can move in and out of raft domains with different partitioning kinetics [28], as well as by coalescing or by breaking up into smaller units [29]. Lipid rafts can also form stabile platforms that are important in signaling, viral infection, and membrane trafficking [24]. Despite a body of evidence supporting the existence of raft domains, the raft concept is still being debated [35] because the mechanisms that govern the associations among sphingolipid, cholesterol, and specific membrane proteins in live cell membranes remain unclear [36]. The controversy is largely due to the lack of standardized methodology for lipid raft studies and the difficulty in proving definitively that rafts exist in living cells without causing significant nonphysiological perturbations by using low temperatures or by extensive cross-linking [37]. The majority of the studies involving lipid rafts begin with detergent solubilization of whole cells followed by sucrose density gradient centrifugation and the recovery of detergent-resistant membranes from the light fractions of the gradient [19, 20]. However, the analysis of density gradient centrifugation experiments remains controversial because there is an indication that detergents may force associations between components that are not colocalized in intact cells [38]. Fractionation results are also known to be severely altered by varying the concentration of Triton X-100 [39, 40], by the use of different detergents, [41, 42], or by omission of detergents in general [43–45]. Another difficulty has been demonstrating the coexistence of l o and l d phases in live cells. However, technological advances have produced compelling data that self-organization of lipids and proteins can induce subcompartmentalization that organizes the bioactivity of cell membranes [31]. Recently, the lipid-based phase separation into liquid-ordered-like and liquid-disordered-like phases has been seen in giant plasma membrane vesicles (GPMVs) obtained by chemically induced blebbing from cultured cells [46, 47] or by using cell swelling to generate plasma membrane spheres (PMS) [48]. In 2010, Johnson et al. [49] using GPMVs showed that peripheral protein binding may be a regulator for lateral heterogeneity in vivo. These new approaches are very promising, allowing studies of the lipid domains in the absence of detergents and other perturbations of membrane structure. Advances in imaging and studies with improved integrated methodologies, such as flotation of detergent-resistant membranes, antibody patching and immunofluorescence microscopy, immunoelectron microscopy, chemical crosslinking, single fluorophore tracking microscopy, photonic force microscopy, spectrofluorimetry, mass spectrometry, and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) are now providing insights into the existence and behavior of lipid rafts [2, 16, 24, 50–56].

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of a lipid raft. Lipid rafts are enriched in cholesterol, sphingolipids, and gangliosides. GPI anchored proteins, sphingomyelin, phosphatidylcholine and gangliosides are present in the outer membrane leaflet. Prenylated proteins, acylated proteins, phosphatidlyserine, and phosphatidylethanolamine are present in the inner leaflet. Cholesterol is present in both leaflets and functions as a space filling molecule under the sphingolipid head groups. TM1, TM2, Transmembrane proteins 1 and 2.

The lipid microdomains are variable in stability, size, shape, lifetime, and molecular composition [29, 37]. Due to differing molecular composition, studies of lipid rafts have also been complicated by imprecise nomenclature [24]. For example, caveolae was synonymous with lipid rafts for many years. In 1998, Harder et al. [57], using a cell system lacking caveolae, demonstrated that raft and nonraft markers segregated in the same cholesterol-dependent way in the absence of caveolae. These results showed that clustered raft markers segregate away from nonraft proteins in a cholesterol-dependent, but caveolin independent manner [56]. Today caveolae are considered a subset of lipid rafts [16, 58].

Membrane rafts in most cell types are enriched with signaling molecules by virtue of the affinity of signaling proteins including transmembrane receptors, GPI anchored proteins, G proteins, RhoA and Src kinases for rafts [1, 35]. The number of proteins reported to be regulated by specific lipid interaction is steadily increasing, but the precise structural mechanisms behind specific binding and receptor regulation in membranes remain uncharacterized [56]. A wealth of biochemical and genetic data have lent credence to the notion that raft function as a specialized signaling platform in cell membranes [59–65]. Most likely, the function of rafts is aided by stimulation-induced association and recruitment of various molecules with raft affinity, as well as varying degrees of raft engagement with the cytoskeleton [3, 4, 29]. Lipid rafts are also thought to be important sites for protein tyrosine kinase-mediated protein-protein interactions that are involved in the initiation of receptor signaling pathways [5, 6, 16]. It is well known that, in the case of tyrosine kinase receptors, adaptors, scaffolding proteins, and enzymes are recruited to the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane as a result of ligand binding to form a signaling complex [66]. If receptor activation takes place in an ordered lipid raft, the signaling complex is protected from other proteins, such as membrane phosphatases, localized in the disordered region of the plasma membrane, that otherwise could affect the signaling process [35, 51, 67]. Lipid rafts are implicated in the function of diverse signaling pathways such as those mediated by growth factors, morphogens, integrins [16] and antigen receptors on immune cells, including mast cells [68–71]. The structural basis for the association of FcεRI with lipid rafts is partially understood and appears to involve the transmembrane segments of FcεRI α and/or γ subunits. However, the structural features of FcεRI that mediate the detergent-sensitive interaction with lipid rafts occur selectively but not uniquely with this receptor [39]. Both β and γ subunits are palmitoylated, which could facilitate their association with lipid rafts [72].

Studies have shown that establishing and maintaining lipid rafts is important for many biological processes besides cell signaling [73, 74]. These membrane microdomains have been implicated in such processes as exocytosis, endocytosis, membrane trafficking, and cell adhesion. The structure-function relationship of lipid rafts or rafts constitutes are important in various aspects of mast cell biology.

2. Morphology

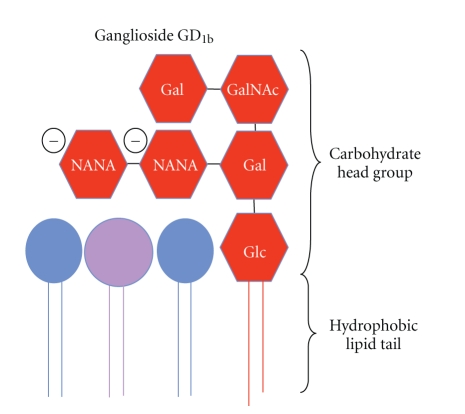

The ability to form lipid rafts appears to be important for maintaining the typical morphology of mast cells. Gangliosides (Figure 2), lipid raft components, are complex glycosphingolipids that are ubiquitous membrane constituents [5, 75–77] and seem to be structurally important for lipid raft assembly and function. The rigid structural nature of the ceramide anchor in gangliosides, coupled with the ability of sphingolipids to associate with cholesterol, is thought to drive the assembly of lipid rafts [16, 78].

Figure 2.

Diagrammatic representation of ganglioside GD1b. The ganglioside is composed of a carbohydrate head group and a hydrophobic lipid tail.

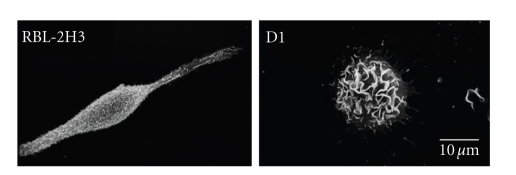

The influence of gangliosides and/or lipid rafts on cell structure and organization was examined [79] using a ganglioside-deficient cell line, D1, and the parent cell line, RBL-2H3, a cell line with homology to mucosal mast cells [80–84]. The D1 cell line is deficient in GM1 gangliosides and in mast cell specific α-galactosyl derivatives of the ganglioside GD1b. The α-galactosyl derivatives of the ganglioside GD1b, antigens I and II, contain, respectively, one and two additional α-galactosyl residues when compared with GD1b. These unique gangliosides are present on the surface of rodent mast cells and are specifically recognized by the monoclonal antibody (mAb) AA4 [85]. These gangliosides derived from GD1b have been identified as components of lipid rafts in the plasma membrane of RBL-2H3 cells [86, 87]. The mutant cell line D1 showed a cellular morphology which is distinct from RBL-2H3 cells (Figure 3), suggesting that the gangliosides are important in the maintenance of normal cell morphology.

Figure 3.

Ganglioside-deficient D1 cells have an altered morphology. By scanning electron microscopy, RBL-2H3 cells are spindle shaped and their surface is covered with short microvilli. In contrast, D1 cells are rounded and their surface is covered with large membrane ruffles.

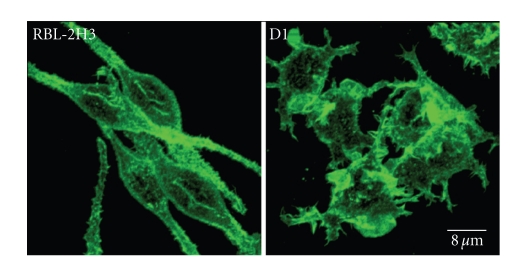

The morphological changes observed in D1 cells could be related to the lipid composition of these cells. This cell line presents a large decrease in glycosphingolipids, such as GM1 and the α-galactosyl derivatives of the ganglioside GD1b, which may affect many physicochemical properties of the plasma membrane. According to Kato et al. [88], the lipid composition could influence membrane stability, membrane fluidity, lipid packing, bilayer curvature, and hydration elasticity, as well as anchorage of the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane. Silveira e Souza et al. [79] also observed that the D1 cells showed an abnormal distribution of actin filaments and microtubules. A growing body of evidence indicates that lipid rafts are essential for membrane-cytoskeleton coupling, and the association of Lyn and other raft markers with crosslinked FcεRI is regulated by interactions with F-actin [89–91]. It is possible that in the D1 mutant cells, the disorganization of both lipid rafts and actin filaments (Figure 4) leads to impaired degranulation after FcεRI stimulation [79, 87]. Furthermore, the actin cytoskeleton is known to participate in regulating and activating raft-associated signaling events [92–94].

Figure 4.

The F-actin distribution in RBL-2H3 and D1 cells reflects their morphology. Actin filaments in RBL-2H3 cells lie under the plasma membrane following the spindle shape of the cells and in association with microvilli. The actin cytoskeleton is altered in D1 cells and the actin filaments are concentrated in large membrane ruffles. The cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with phalloidin conjugated to Alexa 488. Samples were examined using a Leica TCS-NT laser scanning confocal microscope.

The factors that govern the formation of lipid rafts continue to be elucidated, but lipid raft formation often requires actin filaments. The connection between lipid raft proteins and actin filaments can affect the lateral distribution and mobility of these membrane proteins [59, 95]. The extent to which the actin cytoskeleton participates in the formation of membrane rafts is not yet established. Han et al. [96] observed that perturbations in the actin filaments (with cytochalasin D and latrunculin A) affect the organization of lipid rafts in RBL-2H3 cells. Importantly, the actin cytoskeleton is a dynamic structure that changes in response to extracellular signals, and it may therefore represent one mechanism for governing the establishment and distribution of lipid rafts in the plasma membrane [97]. Chichili and Rodgers [98] showed that lipid rafts may be structured by a synergistic interaction between the cortical actin filaments and the lipid rafts themselves, and that many of the structural and functional properties of rafts require an intact actin cytoskeleton. An important regulator of membrane-cytoskeleton interactions is the phosphoinositide PIP2, which is a minor lipid component of the plasma membrane that is known to regulate the organization of the actin cytoskeleton and in particular the formation of actin-membrane linkages [99]. PIP2 also serves as a cofactor for many of the proteins that anchor actin filaments to the plasma membrane [99, 100]. Protein binding to PIP2 often occurs through a PIP2-specific recognition sequence, in many cases represented by a PIP2-specific pleckstrin homology (PH) domain [101–103]. Some actin binding proteins (ABPs) are thought to link actin filaments and PIP2-enriched rafts. Gelsolin is one of the ABPs present in lipid rafts [104]. Microtubules are one of the major determinants of cell shape and polarity [105, 106]. In the ganglioside-deficient D1 cells, the arrangement of microtubules was completely disorganized. The results from this study have demonstrated that the abnormal morphology observed in the mutant cell line could be related to the decrease in gangliosides that leads to lipid raft disorganization [79].

3. Endocytosis

When the concept of lipid rafts and the mobility of proteins in the plasma membrane originated, it was observed that plasma membrane associated proteins could suffer a selective reorganization followed by internalization of these proteins [107–109]. Receptor-mediated endocytosis, including endocytosis of FcεRI, is a temporally and spatially organized process [22, 110]. After activation, crosslinked FcεRI is endocytosed through clathrin-coated vesicles and transported by the endosomal system for eventual degradation in lysosomes [111–113]. In unstimulated mast cells, FcεRI is dispersed throughout the plasma membrane but upon activation the receptors rapidly aggregate and can be found on the cell surface in lipid rafts in association with GM1 [114, 115], gangliosides derived from GD1b, protein tyrosine kinase Lyn and LAT, [22, 39, 86]. However, only when the mast cells are activated via FcεRI does a significant internalization of the GD1b derivatives occur [22, 116]. The endocytosis process itself may play an important role in signal transduction [110, 117]. Oliver et al. [22] showed that upon activation of FcεRI, the gangliosides derived from GD1b are internalized together with the receptor, following the same pathway to lysosomes (Figure 5). This may facilitate the structural preservation of signaling complexes and the prolongation of the signal since these gangliosides and the FcεRI are associated in lipid rafts.

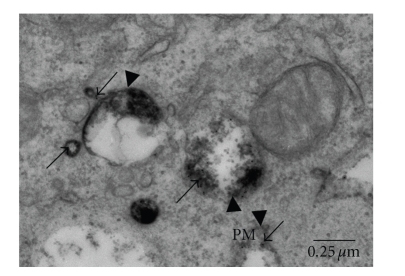

Figure 5.

The gangliosides follow the same endocytic pathway as FcεRI. At 15 minutes of incubation with both mAb BC4-gold (which recognizes the α subunit of FcεRI) and mAb AA4-HRP (which recognizes gangliosides derived from GD1b), the BC4-gold (arrows) and AA4-HRP (arrowheads) are colocalized in early endosomes adjacent to the plasma membrane (PM).

In view of the importance of lipid raft integrity for efficient receptor endocytosis, it has been observed that the FcεRI ubiquitination is a key mechanism for the regulation and control of antigen-dependent endocytosis of receptor complexes [118]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that ubiquitin ligases Cbl and Nedd4 are recruited into lipid rafts upon IgE triggered cell signaling [119]. Nedd4 was shown to ubiquitinate membrane receptors [120]. The ubiquitin Cbl is a good candidate to mediate FcεRI ubiquitination since it participates in various functions such as cis-and-trans-ubiquitination [121]. It is phosphorylated upon FcεRI engagement [122] and negatively regulates Syk kinase [123]. Molfetta et al. [124, 125] suggested that the recruitment of engaged FcεRI subunits into lipid rafts precedes their ubiquitination, and that integrity of lipid rafts is required for receptor ubiquitination and endocytosis, contributing to the down-regulation of FcεRI-mediated signaling.

4. Signal Transduction

In mast cells, the first signaling complex convincingly shown to involve lipid rafts was immunoglobulin E (IgE). IgE signaling was initially thought to be based on protein-protein interactions alone, but several observations indicated that lipid rafts are involved in this process [37, 68, 126–131]. The first hint came from the finding that FcεRI is soluble in Triton X-100 at steady state but becomes insoluble in low concentrations of this detergent after crosslinking [68]. Moreover, in unstimulated cells, FcεRI is dispersed throughout the plasma membrane, but upon activation rapidly aggregates [115, 132] and can then be found on the cell surface in association with the ganglioside GM1 [57, 114, 133] and GPI-anchored proteins [89, 134]. Despite numerous studies on mast cell activation through FcεRI, the detailed mechanism by which cross-linking promotes the initial phosphorylation by Lyn and the molecular mechanisms for Lyn activation are still unclear [67, 77, 135, 136]. Davey et al. [37] suggested that protein-protein interaction (IgE-FcεRI cross-linking) recruits essential signaling proteins and lipid molecules into more ordered domains that serve as a platform for signaling.

An approach intensively used to better understand the role of lipid rafts in FcεRI-mediated signaling has been the study and/or the manipulation of the lipid constituents of rafts, such as cholesterol and gangliosides [16, 87, 136]. Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), a carbohydrate molecule with a pocket for binding cholesterol, [16] is extensively used to deplete the surface cholesterol and subsequently disrupt lipid rafts. MβCD has been used to study the role of lipid rafts in FcεRI-mediated signaling, particularly in early events of signal transduction such as tyrosine phosphorylation of FcεRI by Lyn [136]. Sheets et al. [86] have demonstrated that phosphorylation of FcεRI proceeds in a cholesterol-dependent manner and that cholesterol depletion reduces stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of FcεRI. In parallel to its inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation, cholesterol depletion disrupts the interactions of aggregated FcεRI and Lyn in intact cells. Cholesterol repletion restores receptor phosphorylation together with the structural interactions, providing strong evidence that lipid raft structure, maintained by cholesterol, plays a critical role in the initiation of FcεRI signaling. Cholesterol depletion by MβCD in RBL-2H3 cells also reduced the release of β-hexosaminidase activity in cells stimulated via FcεRI [87, 88, 137, 138]. These data suggest that the cholesterol depletion by MβCD affects the IgE signaling due to the disruption of lipid rafts and consequently results in a failure to form a signaling complex. Moreover, Young et al. [67] showed evidence that Lyn isolated in lipid rafts has substantially higher Lyn kinase activity than Lyn outside of these membrane microdomains. These data suggest that some unknown components in lipid rafts may influence the kinase activity of Lyn [136] and subsequently FcεRI signal transduction.

Flotillin-1 is another constituent of lipid rafts [139, 140]. It was initially identified as a caveolae-associated membrane protein and is a marker protein of lipid rafts, but its physiological role is still not clear. Kato et al. [136] using flotillin-1 knockdown RBL-2H3 cells showed that flotillin-1 regulates the kinase activity of Lyn in mast cells. In the flotillin-1 knockdown cells, there was a significant decrease in Ca2+ mobilization, the phosphorylation of ERKs, tyrosine phosphorylation of the γ-subunit of FcεRI, and IgE-mediated degranulation. This study also showed that flotillin-1 is constitutively associated with Lyn in lipid rafts in RBL-2H3 cells, and that antigen stimulation induced an increase in flotillin-1 binding to Lyn, resulting in enhancement of the kinase activity of Lyn. These data suggest that this raft protein is an important component of FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation and regulates the kinase activity of Lyn in lipid rafts.

The α-galactosyl derivatives of the gangliosides GD1b also seem to be intimately involved with signaling through FcεRI. Although the functional role of these gangliosides is not clear, previous studies have shown that when the α-galactosyl derivatives of ganglioside GD1b are bound by mAb AA4, histamine release was inhibited in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. Binding of mAb AA4 to RBL-2H3 cells resulted in an increase in intracellular calcium, phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis, and a redistribution of PKC. However, the magnitude of these changes was less than those after FcεRI aggregation, and unlike FcεRI activation, these changes were not accompanied by histamine release [81]. The derivatives of the ganglioside GD1b coprecipitated with the Src family tyrosine kinase Lyn and that in spite of the fact that mAb AA4 binds to sites close to FcεRI the association between Lyn and these gangliosides was not mediated by FcεRI. The association of Lyn with these gangliosides is much stronger than the association of Lyn with FcεRI. These associations suggest that a complex of molecules that includes gangliosides, FcεRI, and Lyn is essential for modulation of signal transduction in mast cells [81, 141–144].

Furthermore, analysis of the subcellular distribution of the gangliosides recognized by mAb AA4 and of FcεRI on sucrose gradients showed that, following FcεRI activation, there was a shift in the distribution of the gangliosides to the lipid raft fractions [22, 87]. The movement of these gangliosides into the lipid rafts may be another mechanism that regulates signal transduction in mast cells.

As previously stated, using a cell line deficient in the α-galactosyl derivatives of ganglioside GD1b, as well as the parent cell line, RBL-2H3, Silveira e Souza et al. [87] demonstrated and confirmed the importance of these gangliosides for lipid raft organization and consequently for FcεRI-mediated degranulation in rodent mast cells. In this study, the authors observed a decreased release of β-hexosaminidase activity in the mutant cell line after FcεRI stimulation, but not after exposure to calcium ionophore. These results show that release of β-hexosaminidase activity is calcium-dependent and furthermore indicated that the mutant cell line possesses the capacity to degranulate. Moreover, reduced release of β-hexosaminidase activity in RBL-2H3 cells treated with compounds that inhibit ganglioside synthesis was also observed.

In addition to lipid raft assembly, another possible role for the mast cell-specific gangliosides in signal transduction could be to facilitate the association of Lyn with FcεRI. Because FcεRI itself has no intrinsic kinase activity, the tyrosine phosphorylations induced by receptor cross-linking could be a secondary event that occurs after aggregation of FcεRI and its movement into lipid rafts [143]. Therefore, these lipid raft complexes that include gangliosides, associated proteins, such as Lyn, LAT, flotillin-1 and FcεRI, have an important role in receptor-mediated signal transduction.

Recently, Fifadara et al. [8] reported that mast cells produce structures such as cytonemes or tunneling nanotubes used for intercellular communication and that intercellular communication may be important during allergic and inflammatory responses following costimulation of FcεRI and CCR1. Albeit the process of cytoneme formation remains poorly understood, the fact that cholesterol depletion reduced the formation of cytonemes suggests that lipid rafts may participate in cytoneme formation in mast cells, either by promoting membrane integrity or by participating in cell signaling.

5. Mast Cell Development and Recruitment

The expression of the α-galactosyl derivatives of the ganglioside GD1b on the mast cell surface also appears to be related to mast cell development and recruitment. Previous studies using mAb AA4 showed that the α-galactosyl derivatives of the ganglioside GD1b were present only in mast cells and not in any other cell type in all 23 rat tissues examined [81, 85]. However, in bone marrow, a population of large, poorly differentiated cells, presumably immature mast cells were also stained with mAb AA4 [81]. Later these cells were indeed shown to be very immature and immature mast cells [145, 146]. Since the heterogeneity of the maturing mast cells makes them impossible to separate from other cells on the basis of their density and mAb AA4 binds only to cells which can be identified as mast cells [146, 147], the gangliosides recognized by mAb AA4 may be considered a powerful marker for rodent mast cells.

The ability to characterize the maturation of bone marrow-derived and peritoneal mast cells has been impaired both by the lack of mast cell-specific markers and by the inability to rapidly and efficiently separate mast cells in all stages of maturation from a mixed population of cells [148]. Using mAb AA4 conjugated to tosylactivated Dynabeads 450, Jamur et al. [145] successfully separated mast cells from rat bone marrow and the peritoneal lavage. They [146] then went on to isolate and characterize bone marrow mast cells at various stages of maturation. In this study, the very immature mast cells, which had not been previously described, were identified by the presence of the derivatives of the ganglioside GD1b on their surface. These cells which could not be recognized as mast cells by standard cytological methods contained only a few small cytoplasmic granules. On the other hand, undifferentiated mast cell precursors in the bone marrow do not express the α-galactosyl derivatives of the ganglioside GD1b recognized by mAb AA4. These gangliosides begin to be expressed on the cell surface jointly with FcεRI and at the same time as the initiation of the formation of cytoplasmic granules in very immature mast cells. The gangliosides derived from GD1b continue to be expressed by mast cells in all stages of maturation [149]. These data suggest that mast cell lipid rafts or raft constitutes are related to mast cell maturation and function.

6. Conclusions

Several aspects of raft structure and function in mast cell biology still need to be elucidated. Undoubtedly, lipid rafts and their constitutes play a role in many aspects of mast cell biology, such as activation through FcεRI, morphology, endocytosis, and maturation. Further research to better define the role of lipid rafts in mast cells could offer novel targets for immunotherapies and treatment of diseases in which mast cells and/or their mediators are involved.

Acknowledgment

A. M. M. Silveira e Souza and V. M. Mazucato contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Allende ML, Proia RL. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors and the development of the vascular system. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2002;1582(1–3):222–227. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pralle A, Keller P, Florin EL, Simons K, Hörber JKH. Sphingolipid-cholesterol rafts diffuse as small entities in the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;148(5):997–1007. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.5.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kusumi A, Ike H, Nakada C, Murase K, Fujiwara T. Single-molecule tracking of membrane molecules: plasma membrane compartmentalization and dynamic assembly of raft-philic signaling molecules. Seminars in Immunology. 2005;17(1):3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hancock JF. Lipid rafts: contentious only from simplistic standpoints. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2006;7(6):456–462. doi: 10.1038/nrm1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pike LJ. Lipid rafts: heterogeneity on the high seas. Biochemical Journal. 2004;378(2):281–292. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilfillan AM, Tkaczyk C. Integrated signalling pathways for mast-cell activation. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2006;6(3):218–230. doi: 10.1038/nri1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao KN, Brown MA. Mast cells: multifaceted immune cells with diverse roles in health and disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1143:83–104. doi: 10.1196/annals.1443.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fifadara NH, Beer F, Ono S, Ono SJ. Interaction between activated chemokine receptor 1 and FcεRI at membrane rafts promotes communication and F-actin-rich cytoneme extensions between mast cells. International Immunology. 2010;22(2):113–128. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalesnikoff J, Galli SJ. New developments in mast cell biology. Nature Immunology. 2008;9(11):1215–1223. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaven MA. Our perception of the mast cell from Paul Ehrlich to now. European Journal of Immunology. 2009;39(1):11–25. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crivellato E, Ribatti D, Mallardi F, Beltrami CA. The mast cell: a multifunctional effector cell. Advances in Clinical Pathology. 2003;7(1):13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Almeida Buranello, PA, Moulin MR, Souza DA, Jamur MC, Roque-Barreira MC, Oliver C. The lectin ArtinM induces recruitment of rat mast cells from the bone marrow to the peritoneal cavity. PLoS One. 2010;5(3, article e9776) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Von Bubnoff D, Novak N, Kraft S, Bieber T. The central role of FcεRi in allergy. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2003;28(2):184–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metzger H. The receptor with high affinity for IgE. Immunological Reviews. 1992;(125):37–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinet JP. The high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI): from physiology to pathology. Annual Review of Immunology. 1999;17:931–972. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simons K, Toomre D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nature Reviews. 2000;1(1):31–39. doi: 10.1038/35036052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivera J. Molecular adapters in FcεRI signaling and the allergic response. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2002;14(6):688–693. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00396-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadler MJS, Matthews SA, Turner H, Kinet JP. Signal transduction by the high-affinity immunoglobulin E receptor FcεRI: coupling form to function. Advances in Immunology. 2000;76:325–355. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)76022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivera J, Arudchandran R, Gonzalez-Espinosa C, Manetz TS, Xirasagar S. A perspective: regulation of IgE receptor-mediated mast cell responses by a LAT-organized plasma membrane-localized signaling complex. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2001;124(1–3):137–141. doi: 10.1159/000053692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura T, Hisano M, Inoue Y, Adachi M. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the linker for activator of T cells in mast cells by stimulation with the high affinity IgE receptor. Immunology Letters. 2001;75(2):123–129. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(00)00295-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siraganian RP. Mast cell signal transduction from the high-affinity IgE receptor. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2003;15(6):639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliver C, Fujimura A, Silveira e Souza AMM, De Castro RO, Siraganian RP, Jamur MC. Mast cell-specific gangliosides and FcεRI follow the same endocytic pathway from lipid rafts in RBL-2H3 cells. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2007;55(4):315–325. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7037.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pike LJ. Rafts defined: a report on the Keystone symposium on lipid rafts and cell function. Journal of Lipid Research. 2006;47(7):1597–1598. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E600002-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simons K, Gerl MJ. Revitalizing membrane rafts: new tools and insights. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2010;11(10):688–699. doi: 10.1038/nrm2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simons K, Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387(6633):569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melkonian KA, Ostermeyer AG, Chen JZ, Roth MG, Brown DA. Role of lipid modifications in targeting proteins to detergent-resistant membrane rafts. Many raft proteins are acylated, while few are prenylated. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(6):3910–3917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pike LJ. Lipid rafts: bringing order to chaos. Journal of Lipid Research. 2003;44(4):655–667. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R200021-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajendran L, Simons K. Lipid rafts and membrane dynamics. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118(6):1099–1102. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szöor Á, Szöllosi J, Vereb G. Rafts and the battleships of defense: the multifaceted microdomains for positive and negative signals in immune cells. Immunology Letters. 2010;130(1-2):2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niemelä PS, Hyvönen MT, Vattulainen I. Influence of chain length and unsaturation on sphingomyelin bilayers. Biophysical Journal. 2006;90(3):851–863. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.067371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lingwood D, Simons K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science. 2010;327(5961):46–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1174621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simons K, Vaz WLC. Model systems, lipid rafts, and cell membranes. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 2004;33:269–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.141803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li XM, Momsen MM, Smaby JM, Brockman HL, Brown RE. Cholesterol decreases the interfacial elasticity and detergent solubility of sphingomyelins. Biochemistry. 2001;40(20):5954–5963. doi: 10.1021/bi002791n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown DA, Rose JK. Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains during transport to the apical cell surface. Cell. 1992;68(3):533–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90189-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edidin M. The state of lipid rafts: from model membranes to cells. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 2003;32:257–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaiser H-J, Lingwood D, Levental I, et al. Order of lipid phases in model and plasma membranes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(39):16645–16650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908987106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davey AM, Walvick RP, Liu Y, Heikal AA, Sheets ED. Membrane order and molecular dynamics associated with IgE receptor cross-linking in mast cells. Biophysical Journal. 2007;92(1):343–355. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayor S, Maxfield FR. Insolubility and redistribution of GPI-anchored proteins at the cell surface after detergent treatment. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1995;6(7):929–944. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.7.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Field KA, Holowka D, Baird B. Structural aspects of the association of FcεRI with detergent-resistant membranes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(3):1753–1758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parolini I, Topa S, Sorice M, et al. Phorbol ester-induced disruption of the CD4-Lck complex occurs within a detergent-resistant microdomain of the plasma membrane: involvement of the translocation of activated protein kinase C isoforms. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(20):14176–14187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montixi C, Langlet C, Bernard AM, et al. Engagement of T cell receptor triggers its recruitment to low-density detergent-insoluble membrane domains. EMBO Journal. 1998;17(18):5334–5348. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Surviladze Z, Dráberová L, Kubínová L, Dráber P. Functional heterogeneity of Thy-1 membrane microdomains in rat basophilic leukemia cells. European Journal of Immunology. 1998;28(6):1847–1858. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199806)28:06<1847::AID-IMMU1847>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ilangumaran S, Arni S, Van Echten-Deckert G, Borisch B, Hoessli DC. Microdomain-dependent regulation of Lck and Fyn protein-tyrosine kinases in T lymphocyte plasma membranes. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1999;10(4):891–905. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harder T, Kuhn M. Selective accumulation of raft-associated membrane protein LAT in T cell receptor signaling assemblies. Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;151(2):199–207. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamanaka T, Straumfors A, Morton HC, Fausa O, Brandtzaeg P, Farstad IN. Differential sensitivity to acute cholesterol lowering of activation mediated via the high-affinity IgE receptor and Thy-1 glycoprotein. European Journal of Immunology. 2001;31(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200101)31:1<1::AID-IMMU1>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baumgart T, Hammond AT, Sengupta P, et al. Large-scale fluid/fluid phase separation of proteins and lipids in giant plasma membrane vesicles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(9):3165–3170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611357104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sengupta P, Hammond A, Holowka D, Baird B. Structural determinants for partitioning of lipids and proteins between coexisting fluid phases in giant plasma membrane vesicles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2008;1778(1):20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lingwood D, Ries J, Schwille P, Simons K. Plasma membranes are poised for activation of raft phase coalescence at physiological temperature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(29):10005–10010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804374105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson SA, Stinson BM, Go MS, et al. Temperature-dependent phase behavior and protein partitioning in giant plasma membrane vesicles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2010;1798(7):1427–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varma R, Mayor S. GPI-anchored proteins are organized in submicron domains at the cell surface. Nature. 1998;394(6695):798–801. doi: 10.1038/29563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson BS, Pfeiffer JR, Oliver JM. Observing FcεRI signaling from the inside of the mast cell membrane. Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;149(5):1131–1142. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.5.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parton RG, Richards AA. Lipid rafts and caveolae as portals for endocytosis: new insights and common mechanisms. Traffic. 2003;4(11):724–738. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vereb G, Matkó J, Szöllösi J. Cytometry of fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Methods in Cell Biology. 2004;2004(75):105–152. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)75005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bíró A, Cervenak L, Balogh A, et al. Novel anti-cholesterol monoclonal immunoglobulin G antibodies as probes and potential modulators of membrane raft-dependent immune functions. Journal of Lipid Research. 2007;48(1):19–29. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600158-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gombos I, Steinbach G, Pomozi I, et al. Some new faces of membrane microdomains: a complex confocal fluorescence, differential polarization, and FCS imaging study on live immune cells. Cytometry A. 2008;73(3):220–229. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coskun Ü, Simons K. Membrane rafting: from apical sorting to phase segregation. FEBS Letters. 2010;584(9):1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harder T, Scheiffele P, Verkade P, Simons K. Lipid domain structure of the plasma membrane revealed by patching of membrane components. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;141(4):929–942. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parton RG, Simons K. The multiple faces of caveolae. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(3):185–194. doi: 10.1038/nrm2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodgers W, Glaser M. Distributions of proteins and lipids in the erythrocyte membrane. Biochemistry. 1993;32(47):12591–12598. doi: 10.1021/bi00210a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kabouridis PS, Magee AI, Ley SC. S-acylation of LCK protein tyrosine kinase is essential for its signalling function in T lymphocytes. EMBO Journal. 1997;16(16):4983–4998. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang W, Trible RP, Samelson LE. LAT palmitoylation: its essential role in membrane microdomain targeting and tyrosine phosphorylation during T cell activation. Immunity. 1998;9(2):239–246. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xavier R, Brennan T, Li Q, McCormack C, Seed B. Membrane compartmentation is required for efficient T cell activation. Immunity. 1998;8(6):723–732. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80577-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roy S, Luetterforst R, Harding A, et al. Dominant-negative caveolin inhibits H-Ras function by disrupting cholesterol-rich plasma membrane domains. Nature Cell Biology. 1999;1(2):98–105. doi: 10.1038/10067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Viola A, Schroeder S, Sakakibara Y, Lanzavecchia A. T lymphocyte costimulation mediated by reorganization of membrane microdomains. Science. 1999;283(5402):680–682. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brdička T, Pavlištová D, Leo A, et al. Phosphoprotein associated with glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains (PAG), a novel ubiquitously expressed transmembrane adaptor protein, binds the protein tyrosine kinase Csk and is involved in regulation of T cell activation. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2000;191(9):1591–1604. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hunter AJ, Ottoson N, Boerth N, Koretzky GA, Shimizu Y. Cutting edge: a novel function for the SLAP-130/FYB adapter protein in β integrin signaling and T lymphocyte migration. Journal of Immunology. 2000;164(3):1143–1147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Young RM, Holowka D, Baird B. A lipid raft environment enhances Lyn kinase activity by protecting the active site tyrosine from dephosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(23):20746–20752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211402200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Field KA, Holowka D, Baird B. FcεRI-mediated recruitment of p53/56(lyn) to detergent-resistant membrane domains accompanies cellular signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(20):9201–9205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miceli MC, Moran M, Chung CD, Patel VP, Low T, Zinnanti W. Co-stimulation and counter-stimulation: lipid raft clustering controls TCR signaling and functional outcomes. Seminars in Immunology. 2001;13(2):115–128. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheng PC, Brown BK, Song W, Pierce SK. Translocation of the B cell antigen receptor into lipid rafts reveals a novel step in signaling. Journal of Immunology. 2001;166(6):3693–3701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Holowka D, Baird B. FcεRI as a paradigm for a lipid raft-dependent receptor in hematopoietic cells. Seminars in Immunology. 2001;13(2):99–105. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kinet JP, Alcaraz G, Leonard A, Wank S, Metzger H. Dissociation of the receptor for immunoglobulin E in mild detergents. Biochemistry. 1985;24(15):4117–4124. doi: 10.1021/bi00336a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Furne C, Corset V, Hérincs Z, Cahuzac N, Hueber AO, Mehlen P. The dependence receptor DCC requires lipid raft localization for cell death signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(11):4128–4133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507864103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koenig A, Russell JQ, Rodgers WA, Budd RC. Spatial differences in active caspase-8 defines its role in T-cell activation versus cell death. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2008;15(11):1701–1711. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hakomori -i S. Structure and function of sphingoglycolipids in transmembrane signalling and cell-cell interactions. Biochemical Society Transactions. 1993;21(3):583–595. doi: 10.1042/bst0210583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brown DA, London E. Functions of lipid rafts in biological membranes. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 1998;14:111–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dráber P, Dráberová L. Lipid rafts in mast cell signaling. Molecular Immunology. 2002;38(16–18):1247–1252. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kolter T, Proia RL, Sandhoff K. Combinatorial ganglioside biosynthesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(29):25859–25862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Silveira e Souza AMM, Trindade ES, Jamur MC, Oliver C. Gangliosides are important for the preservation of the structure and organization of RBL-2H3 mast cells. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2010;58(1):83–93. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.954776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Galli SJ. New insights into ‘The riddle of the mast cells’: microenvironmental regulation of mast cell development and phenotypic heterogeneity. Laboratory Investigation. 1990;62(1):5–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oliver C, Sahara N, Kitani S, Robbins AR, Mertz LM, Siraganian RP. Binding of monoclonal antibody AA4 to gangliosides on rat basophilic leukemia cells produces changes similar to those seen with Fcε receptor activation. Journal of Cell Biology. 1992;116(3):635–646. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.3.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yong LCJ. The mast cell: origin, morphology, distribution, and function. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 1997;49(6):409–424. doi: 10.1016/S0940-2993(97)80129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Metcalfe DD, Baram D, Mekori YA. Mast cells. Physiological Reviews. 1997;77(4):1033–1079. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Passante E, Frankish N. The RBL-2H3 cell line: its provenance and suitability as a model for the mast cell. Inflammation Research. 2009;58(11):737–745. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0074-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guo N, Her GR, Reinhold VN, Brennan MJ, Siraganian RP, Ginsburg V. Monoclonal antibody AA4, which inhibits binding of IgE to high affinity receptors on rat basophilic leukemia cells, binds to novel α-galactosyl derivatives of gangliosides G(D1b) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264(22):13267–13272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sheets ED, Holowka D, Baird B. Critical role for cholesterol in Lyn-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of FcεRI and their association with detergent-resistant membranes. Journal of Cell Biology. 1999;145(4):877–887. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Silveira e Souza AMM, Mazucato VM, de Castro RO, et al. The α-galactosyl derivatives of ganglioside GD are essential for the organization of lipid rafts in RBL-2H3 mast cells. Experimental Cell Research. 2008;314(13):2515–2528. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kato N, Nakanishi M, Hirashima N. Cholesterol depletion inhibits store-operated calcium currents and exocytotic membrane fusion in RBL-2H3 cells. Biochemistry. 2003;42(40):11808–11814. doi: 10.1021/bi034758h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Holowka D, Sheets ED, Baird B. Interactions between FcεRI and lipid raft components are regulated by the actin cytoskeleton. Journal of Cell Science. 2000;113(6):1009–1019. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.6.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Levitan I, Gooch KJ. Lipid rafts in membrane-cytoskeleton interactions and control of cellular biomechanics: actions of oxLDL. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2007;9(9):1519–1534. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pike LJ. The challenge of lipid rafts. Journal of Lipid Research. 2009;50:S323–S328. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800040-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bunnell SC, Kapoor V, Trible RP, Zhang W, Samelson LE. Dynamic actin polymerization drives T cell receptor-induced spreading: a role for the signal transduction adaptor LAT. Immunity. 2001;14(3):315–329. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Barda-Saad M, Braiman A, Titerence R, Bunnell SC, Barr VA, Samelson LE. Dynamic molecular interactions linking the T cell antigen receptor to the actin cytoskeleton. Nature Immunology. 2005;6(1):80–89. doi: 10.1038/ni1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gomez TS, Hamann MJ, McCarney S, et al. Dynamin 2 regulates T cell activation by controlling actin polymerization at the immunological synapse. Nature Immunology. 2005;6(3):261–270. doi: 10.1038/ni1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lenne PF, Wawrezinieck L, Conchonaud F, et al. Dynamic molecular confinement in the plasma membrane by microdomains and the cytoskeleton meshwork. EMBO Journal. 2006;25(14):3245–3256. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Han X, Smith NL, Sil D, Holowka DA, McLafferty FW, Baird BA. IgE receptor-mediated alteration of membrane-cytoskeleton interactions revealed by mass spectrometric analysis of detergent-resistant membranes. Biochemistry. 2009;48(27):6540–6550. doi: 10.1021/bi900181w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chichili GR, Rodgers W. Clustering of membrane raft proteins by the actin cytoskeleton. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(50):36682–36691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chichili GR, Rodgers W. Cytoskeleton-membrane interactions in membrane raft structure. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2009;66(14):2319–2328. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0022-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yin HL, Janmey PA. Phosphoinositide regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Annual Review of Physiology. 2003;65:761–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Czech MP. Signal transduction: lipid rafts and insulin action. Nature. 2000;407(6801):147–148. doi: 10.1038/35025183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Harlan JE, Hajduk PJ, Yoon HS, Fesik SW. Pleckstrin homology domains bind to phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Nature. 1994;371(6493):168–170. doi: 10.1038/371168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Várnai P, Balla T. Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: calcium- and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[H]inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;143(2):501–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lemon G, Gibson WG, Bennett MR. Metabotropic receptor activation, desensitization and sequestration - I: modelling calcium and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate dynamics following receptor activation. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2003;223(1):93–111. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(03)00079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Funatsu N, Kumanogoh H, Sokawa Y, Maekawa S. Identification of gelsolin as an actin regulatory component in a Triton insoluble low density fraction (raft) of newborn bovine brain. Neuroscience Research. 2000;36(4):311–317. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(99)00125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ilschner S, Brandt R. The transition of microglia to a ramified phenotype is associated with the formation of stable acetylated and detyrosinated microtubules. Glia. 1996;18(2):129–140. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199610)18:2<129::AID-GLIA5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Conde C, Cáceres A. Microtubule assembly, organization and dynamics in axons and dendrites. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(5):319–332. doi: 10.1038/nrn2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tsan MF, Berlin RD. Effect of phagocytosis on membrane transport of nonelectrolytes. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1971;134(4):1016–1035. doi: 10.1084/jem.134.4.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Edelman GM, Yahara I, Wang JL. Receptor mobility and receptor-cytoplasmic interactions in lymphocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1973;70(5):1442–1446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.5.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Oliver JM, Ukena TE, Berlin RD. Effects of phagocytosis and colchicine on the distribution of lectin binding sites on cell surfaces. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1974;71(2):394–398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.2.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ceresa BP, Schmid SL. Regulation of signal transduction by endocytosis. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2000;12(2):204–210. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stump RF, Pfeiffer JR, Seagrave J, Oliver JM. Mapping gold-labeled IgE receptors on mast cells by scanning electron microscopy: receptor distributions revealed by silver enhancement, backscattered electron imaging, and digital image analysis. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 1988;36(5):493–502. doi: 10.1177/36.5.2965720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mao SY, Pfeiffer JR, Oliver JM, Metzger H. Effects of subunit mutation on the localization to coated pits and internalization of cross-linked IgE-receptor complexes. Journal of Immunology. 1993;151(5):2760–2774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bonifacino JS, Traub LM. Signals for sorting of transmembrane proteins to endosomes and lysosomes. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2003;72:395–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wilson BS, Steinberg SL, Liederman K, et al. Markers for detergent-resistant lipid rafts occupy distinct and dynamic domains in native membranes. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2004;15(6):2580–2592. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wilson BS, Pfeiffer JR, Surviladze Z, Gaudet EA, Oliver JM. High resolution mapping of mast cell membranes reveals primary and secondary domains of FcεRI and LAT. Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;154(3):645–658. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mazucato VM, Silveira e Souza AM, Nicoletti LM, Jamur MC, Oliver C. GD1b-derived gangliosides modulate FcεRI endocytosis. doi: 10.1369/0022155411400868. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.McPherson PS, Kay BK, Hussain NK. Signaling on the endocytic pathway. Traffic. 2001;2(6):375–384. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.002006375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Molfetta R, Gasparrini F, Santoni A, Paolini R. Ubiquitination and endocytosis of the high affinity receptor for IgE. Molecular Immunology. 2010;47(15):2427–2434. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lafont F, Simons K. Raft-partitioning of the ubiquitin ligases Cbl and Nedd4 upon IgE-triggered cell signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(6):3180–3184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051003498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Harvey KF, Kumar S. Nedd4-like proteins: an emerging family of ubiquitin-protein ligases implicated in diverse cellular functions. Trends in Cell Biology. 1999;9(5):166–169. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01541-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Freemont PS. Ubiquitination: RING for destruction? Current Biology. 2000;10(2):R84–R87. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ota Y, Beitz LO, Scharenberg AM, Donovan JA, Kinet JP, Samelson LE. Characterization of Cbl tyrosine phosphorylation and a Cbl-Syk complex in RBL-2H3 cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1996;184(5):1713–1723. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ota Y, Samelson LE. The product of the proto-oncogene c-cbl: a negative regulator of the Syk tyrosine kinase. Science. 1997;276(5311):418–420. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5311.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Molfetta R, Gasparrini F, Peruzzi G, et al. Lipid raft-dependent FcεRI ubiquitination regulates receptor endocytosis through the action of ubiquitin binding adaptors. PLoS One. 2009;4(5, article e5604) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Molfetta R, Gasparrini F, Santoni A, Paolini R. Ubiquitination and endocytosis of the high affinity receptor for IgE. Molecular Immunology. 2010;47(15):2427–2434. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Field KA, Apgar JR, Hong-Geller E, Siraganian RP, Baird B, Holowka D. Mutant RBL mast cells defective in FcεRI signaling and lipid raft biosynthesis are reconstituted by activated Rho-family GTPases. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2000;11(10):3661–3673. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Metzger H. It’s spring, and thoughts turn to ... allergies. Cell. 1999;97(3):287–290. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80738-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hanai N, Nores GA, MacLeod C, Torres-Mendez CR, Hakomori S. Ganglioside-mediated modulation of cell growth. Specific effects of GM and lyso-GM in tyrosine phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263(22):10915–10921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Weis FMB, Davis RJ. Regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor signal transduction. Role of gangliosides. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265(20):12059–12066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Baird B, Sheets ED, Holowka D. How does the plasma membrane participate in cellular signaling by receptors for immunoglobulin E? Biophysical Chemistry. 1999;82(2-3):109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(99)00110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang XQ, Sun P, Paller AS. Ganglioside modulation regulates epithelial cell adhesion and spreading via ganglioside-specific effects on signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(43):40410–40419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Stump RF, Pfeiffer JR, Schneebeck MC, Seagrave JC, Oliver JM. Mapping gold-labeled receptors on cell surfaces by backscattered electron imaging and digital image analysis: studies of the IgE receptor on mast cells. American Journal of Anatomy. 1989;185(2-3):128–141. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001850206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Brown DA, London E. Structure and function of sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich membrane rafts. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(23):17221–17224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Stauffer TP, Meyer T. Compartmentalized IgE receptor-mediated signal transduction in living cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;139(6):1447–1454. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.6.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Pyenta PS, Holowka D, Baird B. Cross-correlation analysis of inner-leaflet-anchored green fluorescent protein co-redistributed with IgE receptors and outer leaflet lipid raft components. Biophysical Journal. 2001;80(5):2120–2132. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76185-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kato N, Nakanishi M, Hirashima N. Flotillin-1 regulates IgE receptor-mediated signaling in rat basophilic leukemia (RBL-2H3) cells. Journal of Immunology. 2006;177(1):147–154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yamashita T, Yamaguchi T, Murakami K, Nagasawa S. Detergent-resistant membrane domains are required for mast cell activation but dispensable for tyrosine phosphorylation upon aggregation of the high affinity receptor for IgE. Journal of Biochemistry. 2001;129(6):861–868. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Fifadara NH, Aye CC, Raghuwanshi SK, Richardson RM, Ono SJ. CCR1 expression and signal transduction by murine BMMC results in secretion of TNF-α, TGFβ-1 and IL-6. International Immunology. 2009;21(8):991–1001. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Volonté D, Galbiati F, Li S, Nishiyama K, Okamoto T, Lisanti MP. Flotillins/cavatellins are differentially expressed in cells and tissues and form a hetero-oligomeric complex with caveolins in vivo: characterization and epitope-mapping of a novel flotillin-1 monoclonal antibody probe. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(18):12702–12709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Bickel PE, Scherer PE, Schnitzer JE, Oh P, Lisanti MP, Lodish HF. Flotillin and epidermal surface antigen define a new family of caveolae-associated integral membrane proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(21):13793–13802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Stracke ML, Basciano LK, Siraganian RP. Binding properties and histamine release in variants of rat basophilic leukemia cells with changes in the IgE receptor. Immunology Letters. 1987;14(4):287–292. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(87)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Stephan V, Guo N, Ginsburg V, Siraganian RP. Immunoprecipitation of membrane proteins from rat basophilic leukemia cells by the antiganglioside monoclonal antibody AA4. Journal of Immunology. 1991;146(12):4271–4277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Minoguchi K, Swaim WD, Berenstein EH, Siraganian RP. Src family tyrosine kinase p53/56lyn, a serine kinase and FcεRI associate with α-galactosyl derivatives of ganglioside GDlb in rat basophilic leukemia RBL-2H3 cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(7):5249–5254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Swaim WD, Minoguchi K, Oliver C, et al. The anti-ganglioside monoclonal antibody AA4 induces protein tyrosine phosphorylations, but not degranulation, in rat basophilic leukemia cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(30):19466–19473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Jamur MC, Grodzki ACG, Moreno AN, Swaim WD, Siraganian RP, Oliver C. Immunomagnetic isolation of rat bone marrow-derived and peritoneal mast cells. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 1997;45(12):1715–1722. doi: 10.1177/002215549704501215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Jamur MC, Grodzki ACG, Moreno AN, et al. Identification and isolation of rat bone marrow-derived mast cells using the mast cell-specific monoclonal antibody AA4. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2001;49(2):219–228. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Faraco CD, Vugman I, Siraganian RP, Jamur MC, Oliver C. Immunocytochemical identification of immature rat peritoneal mast cells using a monoclonal antibody specific for rat mast cells. Acta Histochemica. 1997;99(1):23–27. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(97)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Valent P, Sillaber C, Bettelheim P. The growth and differentiation of mast cells. Progress in Growth Factor Research. 1991;3(1):27–41. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(91)90011-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Jamur MC, Grodzki ACG, Berenstein EH, Hamawy MM, Siraganian RP, Oliver C. Identification and characterization of undifferentiated mast cells in mouse bone marrow. Blood. 2005;105(11):4282–4289. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]