Abstract

A mouse model has been extensively used to investigate disease intervention approaches and correlates of immunity following influenza virus infection. The majority of studies examining cross-reactive and protective immune responses have used intranasal (IN) virus inoculation; however, infectious aerosols are a common means of transmitting influenza in the human population. In this study, IN and aerosol routes of inoculation were compared and end-points of immunity and disease pathogenesis were evaluated in mice using mouse-adapted H3N2 A/Aichi/2/68 (x31). Aerosol inoculation with sub-lethal x31 levels caused more robust infection, which was characterized by enhanced morbidity, mortality, pulmonary cell infiltration, and inflammation, compared to IN-inoculated mice, as well as higher levels of IL-6 expression in the lung. Treatment with IL-6-blocking antibodies reduced pulmonary infiltrates and lung pathology in aerosol-inoculated mice. This study shows that aerosol inoculation results in a distinctive host response and disease outcome compared to IN inoculation, and suggests a possible role for IL-6 in lung pathogenesis.

Introduction

Influenza virus infection can cause a range of clinical symptoms, from asymptomatic to viral pneumonia, resulting in at least 200,000 hospitalizations and an estimated 36,000 deaths in the United States annually (50,51). Influenza can be transmitted by aerosol and by direct contact with secretions or fomites (22,32,52); however, infectious aerosols are a common means of transmitting influenza because suspensions can remain airborne for prolonged periods where they can be inhaled (49). Importantly, the distribution of aerosol particles in the respiratory tract corresponds to the particle sizes inhaled. Particles of >5 μm median aerosol diameter generally locate to the upper respiratory tract, whereas particles <5 μm median aerosol diameter can traverse the entire airway and deposit in the lungs (25,26). Experimental studies with influenza in human volunteers have shown that the infectious dose is considerably smaller when the virus is delivered by aerosol compared to intranasal (IN) inoculation, with typical clinical signs observed only after aerosol infection (1,30).

Efforts to understand the host response to influenza virus infection or vaccination have used a variety of animal species (52); however, the foremost animal models include mice and ferrets (52,54). Despite a lack of natural susceptibility to human influenza viruses, mice provide a well-characterized model with predictive efficacy for the study of the immune response to infection (53) through adapted viruses (4,52). The majority of mouse studies have investigated IN infection or challenge that predominantly results in localized lower respiratory tract infection, despite the fact that all airway epithelial cells of the bronchi and alveoli are susceptible (34). Typical influenza viruses used in the mouse model include strains H1N1 A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (PR8) and H3N2 A/Aichi/2/68 (x31), a reassortant that contains the six internal genes of PR8, and the surface hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) from a prototypical H3N2 virus (12). These mouse-adapted influenza viruses are antigenically distinct, which makes them useful for evaluating primary and memory immune responses without interference from neutralizing antibody responses. These viruses have been extensively studied to determine the relative importance of immune defense activities that control infection. The lethal doses (LD50) of x31 and PR8 in mice after IN inoculation are different, as x31 is sub-lethal and PR8 is lethal at low doses (15,35). Few studies have compared aerosol to IN inoculation with these prototypical laboratory strains. In one study, mice were first inoculated by either route, and then challenged 42 d later with homologous virus delivered by the same or alternative route. Three days after challenge, pulmonary virus titers were determined, and the results showed that IN inoculation appeared to be more effective, both in inducing and challenging immunity from a previous infection (24). In a related study, aerosol inoculation with PR8 resulted in virus replication in lung tissues similar to natural infection in humans, suggesting that the course of infection was affected by the mode of virus administration (13).

The importance of particle size has been considered for aerosol delivery of influenza virus and in vaccination. It has been shown in mice that large-particle (10 μm median diameter) aerosols are primarily localized to the upper respiratory tract, and that such particle sizes require greater virus doses to initiate infection and stimulate antibody production than smaller-particle (2 μm median diameter) aerosols (42). In the same study, it was also shown that mice immunized with small-particle aerosols were resistant to challenge with a lethal dose of virus (A/Aichi/2/68), whereas large-particle-immunized mice were not protected. Consistent with these findings, a related study examined vaccination of mice with large (8 μm) or small (2 μm) particles of attenuated recombinant influenza (H3N2) virus, and showed that serum-neutralizing and hemagglutinin-inhibition (HAI) antibodies were detected in all vaccinated mice by 28 d, but HAI and neutralizing antibodies were only detected in the small-particle-vaccinated group (23). In addition, it was also shown that small-particle-vaccinated mice were fully protected after challenge with a virulent, mouse-adapted variant of A/Aichi/2/68 (H3N2), whereas only 89% of the larger-particle group survived. These results show that influenza aerosol particle size and distribution are important in the concomitant host response to infection.

In this study, we examined how the method of inoculation affected immune and disease outcomes using a mouse model of influenza virus infection with the prototypic strain x31. Our results show that aerosol inoculation with x31 caused more severe lung pathology and enhanced morbidity and mortality compared to IN inoculation with x31. In addition, our data suggest that enhanced disease may be associated with increased pulmonary IL-6 expression. The results of this study have important implications for interpreting the relevant host responses in studies examining IN inoculation of influenza virus, and in understanding the features of disease pathogenesis attributed to aerosol infection with influenza virus.

Materials and Methods

Viruses

Mouse-adapted H3N2 reassortant A/Aichi/2/68 (x31) and H1N1 A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (PR8) were grown in the allantoic cavity of 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs for 48 h at 37°C. Stock virus was aliquotted and stored at −80°C until use. The 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of each virus was determined by the Reed and Meunch method (40).

Mice and inoculations

Six- to 8-week-old specific-pathogen-free female BALB/c mice (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were housed in microisolator cages, and food and water were provided ad libitum. The studies were reviewed and approved by the university institutional animal care and use committee. The mice were anesthetized with 0.2 mL Aveitin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol) by IP injection prior to inoculation with or aerosol exposure to x31 virus. The mice were inoculated by IN instillation of 0.05 mL/nare, for a total inoculation of 0.1 mL with 106 TCID50/mL x31 virus. The same virus suspension was used for aerosol delivery to the mice. Each mouse was individually inoculated for 45 sec using a nebulizer (Creare Inc., Hanover, NH) with a hydrophobic plastic cone that covered the nares and mouth of the mice. The mice were exposed to approximately 750 μL of virus suspension, based on exposure time at a flow rate of 1 cc/min. The nebulizer delivered a 30-μm median particle size, which represents the mean under the curve of particle sizes, utilizing an ultrasonic vibrating mesh technology and disposable aerosolizing elements, with very few (<1% by volume) respirable particles as determined by the device manufacturer. The air and liquid flow rate was controlled by an internal or external pump, and these parameters can be adjusted by the user. The particle size and viability of virus after aerosol delivery were determined by the device manufacturer, as well as by our laboratory, using a next-generation cascade impactor having seven impaction stages, with D50 values between 0.54 and 6.12 μm at all design flow rates. There was no detectable loss of influenza virus viability post-nebulization, as determined by infectious virus plaque assay (data not shown). The 50% mouse lethal dose (MLD50) was determined as previously described (6). Briefly, five mice per group were inoculated by IN instillation or aerosol exposure with 10-fold dilutions (106−102 TCID50/mL) of x31 virus. Clinical disease signs (ruffled fur and inappetence) and weights of the mice were recorded daily for 14 d. Mice with weight loss of ≥20% were euthanized. Moribund mice were sacrificed and the lungs were perfused with 10% normal buffered formalin for histopathological examination by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining or immunohistochemical staining. It was assumed that the animals inhaled about half of what they were exposed to based on related published reports (44); however, the MLD50 was calculated by the Reed and Meunch method (40), and given as the TCID50 value of the virus suspension that the mice were exposed to, and not on the amount of virus that was theoretically inhaled.

Lung virus titers and sampling

Nasal washes and lungs were obtained from five mice per group at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 days post-inoculation (dpi), and the samples were frozen at −80°C until virus titers were determined. Nasal washes of the mice were performed using 0.5 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin, penicillin (4000 U/mL; Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ), streptomycin (800 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), polymyxin B (400 U/mL; MP Biochemicals, LLC, Solon, OH), and gentamicin (100 μg/mL; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA). The nasal washes were thawed in a 37°C water bath and mixed before use. To prepare lung tissue, 1 mL of PBS containing antibiotics and 0.5% bovine serum albumin was added to each sample. The samples were homogenized using a TissueLyser (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. A TCID50 was used to determine virus titers for each sample as previously described (16). Briefly, 10-fold serial dilutions of the specimens were made in modified Eagle's medium (MEM), with TPCK [L-(tosylamido-2-pheyl) ethyl chloromethyl ketone]-treated trypsin (1 μg/mL; Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ). Dilutions of each sample were added to Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (four wells for each dilution, 200 μL/well), and the cells were incubated for 48 h at 37°C. The contents of each well were tested for hemagglutination, and the TCID50 was calculated by the Reed and Meunch method (40).

Hemagglutination inhibition

Serum samples were collected from each mouse prior to inoculation and at 14 dpi. All sera were treated with receptor-destroying enzyme (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY), and tested for inhibitory antibodies in an HAI with 0.5% chicken red blood cells) as previously described (55). The viruses were diluted to contain four agglutinating units in sterile PBS.

Histopathological examination

For histopathological examination, the lungs were harvested from the mice in each group at 1, 3, 5, and 7 dpi, and fixed by inflation and immersion in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). Formalin-fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned (4 μm thick; Leica Autocut microtome 2055; Leica, Solms, Germany), and placed on glass slides. To evaluate inflammation and lesions, fixed lung sections were subjected to H&E staining and scored (0 [none] to 3 [extreme]) on the basis of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cell infiltration, perivascular and peribronchiolar cuffing, and by extent of lung involvement.

Immunohistochemical staining for the detection of influenza viral antigen in lung sections was performed as previously described (19). Briefly, the slides were de-paraffinized using Histo-choice (Amersco, Solon, OH), and rehydrated in graduated ethanol baths. The lung sections were treated in 10 mM citric acid (pH 6) as described previously (12). The slides were then treated with 3% H2O2 for 20 min., blocked using an avidin-biotin block and Serum Free Protein Block (Dako USA, Carpinteria, CA) for 30 min., and incubated with influenza NP-specific monoclonal antibody (Biodesign International, Saco, ME) for 60 min at 37°C. The slides were washed with PBS (three times for 3 min each at room temperature), incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse antibody for 60 min at room temperature, and then with ABC substrate according to the manufacturer's specifications (ABC elite KIT; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used as chromogen, and the slides were lightly counter-stained with Lillie-Mayer hematoxylin for 2 min., and mounted using Permount mounting medium (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ).

Flow cytometry

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was collected from five mice per infection group at 1, 3, or 6 dpi, as previously described (3). Uninfected mice and mice administered PBS by IN or aerosol were used as controls. Red blood cells were lysed with BD Pharm Lyse buffer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 10 min at room temperature. Viable BAL cell counts were determined by light microscopic examination using trypan blue exclusion. The cells were subsequently washed twice with PBS containing 1% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 0.1% sodium azide (PBS-FBS), and incubated at 4°C for 20 min with anti-mouse CD3-Alexa Fluor 647 (17A2), CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5 (RM4-5), and CD8a-APC-Cy7 (53-6.7), or CD3-Alexa Fluor 647 (17A2), CD45R-PerCP-Cy5.5 (RA3-6B2), CD49b-FITC (DX5), Ly6G/C-PE (RB6-8C5), and CD11b-APC-Cy7 (M1/70), or appropriate isotype controls (all from BD Biosciences). The cells were washed twice with PBS-FBS and fixed with 2% formaldehyde (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) in PBS, prior to data acquisition on a LSR-II flow cytometer using FACSDiva 4.1.2 software (BD Biosciences).

Measurement of intracellular hydrogen peroxide

The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) was measured using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate as a fluorescent probe as previously described (47). Briefly, 50 μM H2DCF [6-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, di (acetoxymethyl ester)]; (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The washed cells were subsequently incubated with 1 μg/mL of PE-Cy7 conjugated anti-Ly6G/C, clone RB6-8C5 (BD Biosciences), for 20 min at 4°C. Fluorescent 2′7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) levels were determined in Ly6G/C+ cells by flow cytometry.

Measurement of cytokine concentrations

A multiplexed assay using the Milliplex MAP system kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used to quantify multiple cytokines simultaneously in BAL fluid from IN- and aerosol-infected mice (7). Briefly, BAL fluid was collected from five mice per infection group at 1, 3, or 6 dpi, as previously described (3). Capture monoclonal antibodies specific for mouse IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-15, IL-17, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, covalently coupled to individual microsphere bead sets by the manufacturer, were multiplexed and mixed with BAL specimens, standards, or controls, in 96-well filter plates as previously described (7). After overnight incubation at 4°C with gentle shaking, unbound extraneous material and buffer was aspirated through the filter plate using an ELx50 plate washer (BioTek, Winooski, VT), and the beads were washed twice with kit wash buffer. The beads were resuspended with biotinylated detection monoclonal antibodies and incubated at room temperature for 60 min with gentle shaking. Streptavidin-phycoerythrin was added to each well and the plate was incubated at room temperature for an additional 30 min with gentle shaking. Finally, the beads were washed twice to remove excess streptavidin-phycoerythrin and resuspended in PBS for analysis using a Luminex-200 System (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX), and xPONENT 3.0.380.0 software (Millipore).

Prophylactic anti-IL-6 treatment

The mice were divided into groups of nine mice per group, and IP injected with 0.5 μg of either a purified rat IgG isotype control antibody (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN), or a monoclonal anti-mouse IL-6 antibody (R&D Systems, Inc.) in 100 μL PBS. The mice were inoculated with x31 by aerosol exposure 24 h after treatment, and were euthanized at 3 dpi for sample collection. Lungs were harvested from three mice per group to determine virus titers. Lungs from an additional three mice per group were harvested for histopathological examination. BAL fluid was collected from the remaining three mice per group for cytokine analysis. The samples were processed as previously described.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U test for unpaired samples was used to compare the responses between aerosol- and IN-inoculated mice. A two-tailed Student's t-test for unpaired samples was used to compare the cytokine response between IN- and aerosol-inoculated mice. GraphPad Prism version 5.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), and Microsoft Excel were used for statistical analysis. Differences with p values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Aerosol inoculation of sub-lethal x31 causes mortality

A/Aichi/2/68 (x31) is a sub-lethal mouse-adapted strain of influenza A virus that has been previously reported to have a high MLD50 (2,3), and IN inoculation with a dose of virus equivalent to 600 hemagglutinating units (HAU) induces a severe but nonfatal pneumonia (9). The MLD50 of x31 was evaluated after IN or aerosol inoculation. At 1 dpi, the mice in the aerosol group exhibited clinical signs of illness (ruffled fur), at 2 dpi they exhibited more substantial signs of illness (huddling and inappetence), and by 4 dpi the mice began to succumb to infection. In contrast, IN-inoculated mice showed no signs of clinical illness out to 4 dpi, with only a few of the mice showing mild signs of illness (ruffled fur) at 5 dpi, but by 8 dpi some mortality had occurred. The results show that the MLD50 of x31 by aerosol infection is considerably lower (105.2 TCID50) than that for IN infection (>106.7 TCID50).

Differences in mortality are not associated with higher levels of virus replication

To determine if the differences in virus titers contributed to differences in mortality after aerosol or IN inoculation, the levels of infectious virus were determined in the nasal washes and lungs (Fig. 1). The amount of virus isolated from the nasal washes of mice was not significantly different at any time point after inoculation. Peak virus titers in nasal washes were evident at 3 dpi, and were similar for aerosol- (104.7 TCID50 /mL) and IN-inoculated (105.4 TCID50 /mL) mice. At 7 dpi, virus titers in nasal wash samples were at or below the limit of detection, with the exception of one IN-inoculated mouse and two aerosol-inoculated mice. By 10 dpi, virus was no longer detectable in either group of mice (data not shown).

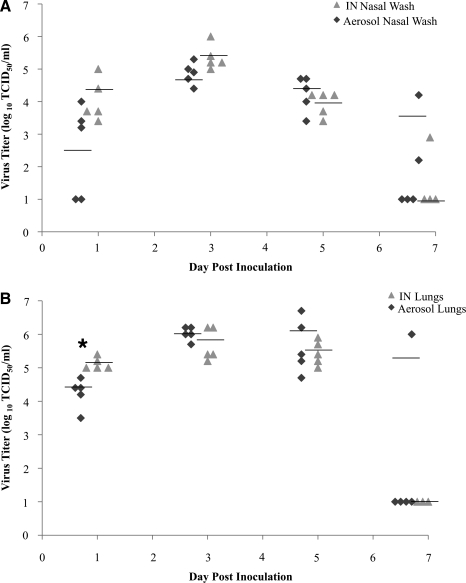

FIG. 1.

Replication kinetics of x31 in mice following aerosol or intranasal (IN) infection. Virus titers (log10 TCID50/mL) in nasal washes (A) and lungs of mice (B). Groups of five mice were used for each time point. Each point represents the value in an inoculated mouse, and the line represents the mean virus titer for each group (*p < 0.05 by Mann-Whitney U test; TCID50, 50% tissue culture infectious dose).

At 1 dpi, there was significantly (p < 0.05) less virus detected in the lungs of aerosol-exposed mice compared to IN-inoculated mice. The levels of infectious virus in the lungs of aerosol- and IN-inoculated mice were similar from 3 to 7 dpi, with peak virus titers (range 105.8−106.0 TCID50/mL) occurring at 3 dpi (Fig. 1B). Virus was isolated from the lungs (106.0 TCID50/mL) of one mouse in the aerosol-inoculated group at 7 dpi; however, lung virus titers for IN-inoculated mice were at or below the limit of detection. By 10 dpi, no infectious virus was detected in the lungs of aerosol- or IN-inoculated mice (data not shown). These results suggest that the differences in mortality observed between aerosol and IN inoculation are not linked to differences in virus titer.

Lung pathology was more extensive in aerosol-inoculated mice

Histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were performed on the lungs of aerosol- or IN-inoculated mice to determine the level of lung pathology associated with infection (Table 1 and Figs. 2 and 3). The magnitude and breadth of lung pathology was more severe in aerosol-inoculated than in IN-inoculated mice. Aerosol-inoculated mice had more severe bronchointerstitial pneumonia across all lung lobes, and evidence of acute alveolar injury with necrosis of the lung airways, including alveoli filled with fibrin, hemorrhage, and neutrophils in the alveolar lumen, and lesions appeared earlier after infection than in IN-inoculated animals. At 1 and 3 dpi, 25–50% of the lung structure in aerosol-inoculated mice exhibited alveolar wall necrosis with exudate in the alveolar lumen (Table 1 and Fig. 2B and D). Lung pathology for IN-inoculated mice was typically confined to one lung lobe with no substantial pathology evident until 3 dpi, when neutrophilic infiltrates and bronchiolar epithelial cells filled the bronchiolar lumen (Fig. 2C).

Table 1.

Severity of Pulmonary Lesions in Mice After Inoculation With x31

|

Severitya[extent (% of anatomical structures affected)] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Aerosol |

Intranasal |

||||||

| Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 7 | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 7 | |

| Necrosis/bronchiolar epithelium | + | + | +++ | 0 | 0/+ | +++ | ++ | + |

| (0–25) | (0–25) | (25–50) | (0) | (0–25) | (25–50) | (25–50) | (0–25) | |

| Necrosis/alveolar wall | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | 0 | + | ++ | + |

| (0–25) | (25–50) | (0–25) | (0–25) | (0) | (0–25) | (0–25) | (0–25) | |

| Exudate/alveolar lumen | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | 0 | + | + | + |

| (0–25) | (25–50) | (0–25) | (0–25) | (0) | (0–25) | (0–25) | (0–25) | |

0/+, minimal; +, mild; ++, moderate; +++, severe.

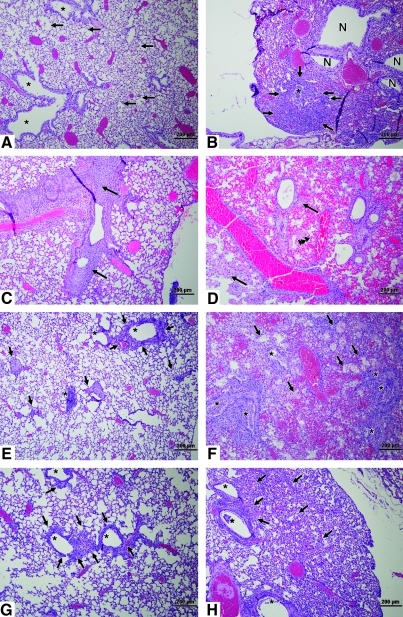

FIG. 2.

Histopathology in the lungs of mice. Shown are hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained images from IN-inoculated (A, C, E, and G), or aerosol-exposed (B, D, F, and H) mice (scale bars = 200 μm). (A) At 1 dpi, bronchiole linings (asterisks) are intact, and the lumina, terminal bronchioles, and alveoli are clear (arrows). (B) At 1 dpi, a single bronchiole (asterisk) is filled with inflammatory infiltrate and necrotic epithelial cells with proximal areas of inflammation (arrows). (C) At 3 dpi, a dense neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate with desquamated bronchiolar epithelial cells fill the bronchiolar lumen (arrows). (D) At 3 dpi, the lung is consolidated, with inflammation present around airways and blood vessels; necrotic areas are also evident (arrows). Fibrin was present in the lumina of necrotic alveoli (arrowheads). (E) At 5 dpi, scattered inflammation is associated with bronchioles (asterisks), and in alveolar spaces (arrows). (F) At 5 dpi, bronchioles (asterisks) are difficult to distinguish because of the extensive inflammatory exudate and necrotic epithelial cells filling the lumina. Arrows indicate still-recognizable alveolar spaces. (G) At 7 dpi, inflammation (arrows) is present around bronchioles (asterisks). (H) At 7 dpi, bronchioles (asterisks) contain moderate inflammatory exudate and necrotic epithelial cells, and intervening alveolar spaces contain dense cellular infiltrate (arrows) with thickened alveolar walls. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/vim.

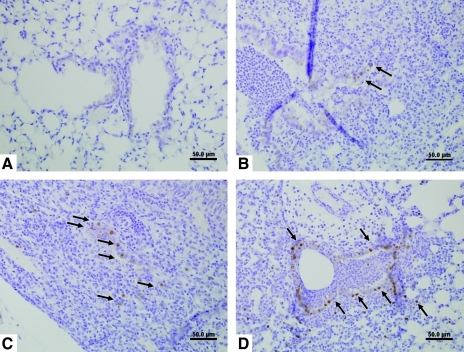

FIG. 3.

Immunostaining for viral antigen from IN- (A and C) and aerosol-inoculated (B and D) mice (scale bars = 50 μm). (A) At 1 dpi, no virus antigen was detected. (B) At 1 dpi, virus antigen was detected in bronchiolar epithelial cells (arrows). (C) At 3 dpi, virus antigen was detected within bronchiolar epithelial cells, and inflammatory cells surround the bronchiole (arrows). (D) At 3 dpi, virus antigen was detected in the majority of bronchiolar epithelial cells, and among inflammatory cells surrounding an affected bronchiole (arrows). Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/vim.

As x31 infection progressed at 5 and 7 dpi in aerosol- and IN-inoculated mice, the more distal airway portions became involved (Fig. 2). For IN-inoculated mice, the primary disease manifestation was necrosis and recruitment of neutrophils (Fig. 2E), whereas for aerosol-inoculated mice, there was a greater extent of lung damage (Table 1 and Fig. 2F and H). At 5 dpi, 50–75% of lung anatomical structures showed severe infection, with evidence of bronchiolar epithelium and alveolar wall necrosis, and exudates in the alveolar lumina of the aerosol-inoculated group, compared to IN-inoculated mice, which showed mild to moderate lung pathology, with inflammation around the bronchioles and alveolar spaces (Table 1 and Fig. 2E and F). In addition, aerosol-inoculated mice had significant inflammation centered in the bronchioles, which were filled with neutrophilic infiltrates and necrotic epithelial cells, with inflammation spilling over into the adjacent alveoli, indicating the development of bronchiolitis and alveolitis (Fig. 2F). At 7 dpi, inflammation was present around the bronchioles of IN-inoculated mice (Fig. 2G), while the bronchioles of aerosol-exposed mice contained inflammatory exudates and necrotic epithelial cells (Fig. 2H). The striking contrast in lung pathology between IN-inoculated (Fig. 2E) and aerosol-inoculated mice (Fig. 2F) suggests that the differences in mortality observed for the different routes of infection are associated with more severe lung pathology and extent of lung involvement.

To determine if histopathology correlated with the presence of viral antigen, IHC was performed and showed that viral antigen was present at sites of lung pathology in aerosol- and IN-inoculated mice (Fig. 3). Discrete staining was detected in the lungs of aerosol-inoculated mice at 1 dpi (Fig. 3B); however, strong staining was evident in the majority of bronchiolar epithelial cells and in some inflammatory cells surrounding the affected bronchiole at 3 dpi (arrows in Fig. 3D). In contrast, no staining was present in IN-inoculated mice at 1 dpi (Fig. 3A); however, at 3 dpi, virus antigen was detected in the bronchiolar lumen and along scattered bronchiolar epithelial cells (arrows in Fig. 3C). At 7 dpi, no appreciable influenza virus antigen was detected in the lungs of either IN- or aerosol-inoculated mice (data not shown).

Immune inflammatory cell infiltration is more extensive in aerosol-inoculated mice

To elucidate features of the immune response that may contribute to the rapid and severe pathology associated with aerosol inoculation, the total numbers and type of leukocytes in BAL fluid samples were determined in both aerosol- and IN-inoculated mice. Controls included un-inoculated mice and mice administered PBS by IN or aerosol exposure. Total mean cell counts for controls were <105 viable cells/mL, and there was no difference in the number of cells in BAL fluid from un-inoculated mice and mice administered sterile PBS by either route. The mean total cell counts in aerosol-inoculated mice at 3 dpi (2.9 × 106 WBC/mL) were significantly higher compared to IN inoculation (1.45 × 106 WBC/mL; Fig. 4A); however, there was no significant difference in mean cell counts between the two groups at 1 or 6 dpi. At 3 dpi, analysis of the numbers of T-helper cells (CD3+/CD4+), cytotoxic T cells (CD3+/CD8+), B cells (CD45R+), NK cells (CD49b+), PMNs (Ly6G/C+), macrophages (Ly6G/C−,CD11b+), and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) (CD45R−/Ly6G/C+/CD11b+), showed PMNs were the most prevalent cell type (67.5% in the aerosol group and 49.9% in the IN group), followed by macrophages (9.6% in the aerosol group 9.5% in the IN group), B cells (2.6% in the aerosol group and 2.4% in the IN group), pDCs (2.4% in the aerosol group and 2.1% in the IN group), and NK cells (2.2% in the aerosol group and 2.0% in the IN group). As expected, few CD3+ cell types were present in the BAL fluid at 3 dpi (data not shown). The numbers of CD4+ T cells (104.3 cells/mL), PMNs (106.3 cells/mL), and pDCs (104.8 cells/mL) in the BAL fluid were significantly higher in aerosol-inoculated mice than in IN-inoculated mice (103.8, 105.9, and 104.4 cells/mL, respectively; Fig. 4B). The high degree of neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrates suggests that these cell types may be contributing to the observed lung pathology.

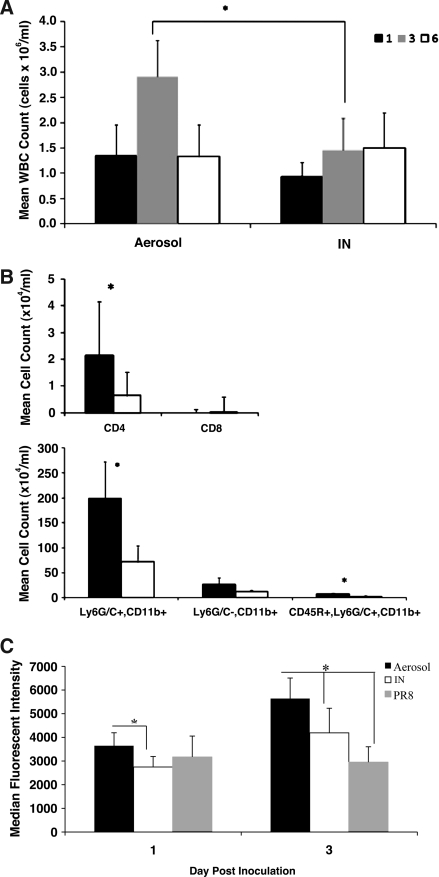

FIG. 4.

Inflammatory cell infiltrates in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of mice after aerosol or IN inoculation. (A) Mean total viable cell counts from the BAL fluids of mice at different time points after inoculation with x31. (B) Cell populations in the BAL fluids of mice at 3 dpi in aerosol- (black bars) or IN-inoculated mice (white bars) as measured by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean of five mice per group. (C) Levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in Ly6G/C+ cells at 1 and 3 dpi (*p < 0.05 by two-tailed Student's t-test).

The level of lung granular cell activation is higher in aerosol-inoculated mice

Activated neutrophils can non-specifically injure host tissues by the release of reactive oxygen intermediates that are produced to control pathogens (47). The production of ROS by granular cells was determined to evaluate the level of activity dominated by PMNs in the BAL fluid that could contribute to lung pathology. BAL fluid cells were collected from aerosol- and IN-infected mice at 1 and 3 dpi and evaluated for ROS production. Controls for this study were mice IN inoculated with PR8. PMNs from aerosol-infected mice had significantly higher ROS activity at 1 and 3 dpi than did PMNs from IN-infected mice (Fig. 4C), suggesting that activated granular cells in the BAL of aerosol-infected mice may have contributed to the more severe lung pathology.

Aerosol inoculation induces greater IL-6 and reduced IFN-γ expression in the lungs of infected mice

To determine differences in the pattern and magnitude of expression in the lungs of aerosol- or IN-infected mice, cytokines were measured in the non-cellular fraction of BAL fluid at 1, 3, and 6 dpi. Consistent with the finding of no significant differences in mean BAL cell counts between aerosol- and IN-infected mice at 1 or 6 dpi, there were also no significant differences in cytokine levels between aerosol- and IN-infected mice (data not shown). However, considerable differences in the levels of IFN-γ, IL-5, and IL-6 expression were identified at 3 dpi for IN- and aerosol-infected mice, based on the combined results from two independent experiments (Table 2). The level of IFN-γ was significantly lower in aerosol- than in IN-infected mice, while the levels of IL-5 and IL-6 were significantly higher in aerosol- than in IN-infected mice. All other cytokine levels examined (IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-15, and IL-17) were very low or below the limit of detection for both groups, and there was no significant difference in levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-12, and TNF-α between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cytokine Levels in BAL Fluid of Mice after Inoculation with x31

| |

Day 3 post-infection |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine (pg/mL) | Intranasala | Aerosol | p Value |

| IL-2 | ND | ND | |

| IL-12 | 3.3 ± 8.1 | 16.8 ± 47.4 | 0.60 |

| IFN γ | 252.4 ± 190.1 | 43.6 ± 69.6 | <0.01 |

| TNF α | 65.1 ± 39.6 | 71.3 ± 57.0 | 0.92 |

| IL-4 | ND | ND | |

| IL-5 | ND | 15.5 ± 15.0 | <0.01 |

| IL-6 | 349.5 ± 170.6 | 3171.5 ± 3751.0 | <0.01 |

| IL-10 | ND | ND | |

| IL-1α | ND | 8.7 ± 15.5 | |

| IL-1β | 5.7 ± 9.0 | 7.4 ± 11.2 | 0.87 |

| IL-15 | ND | ND | |

| IL-17 | ND | 3.3 ± 6.6 | 0.12 |

n = 13 for each group.

ND, below the limit of detection; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage.

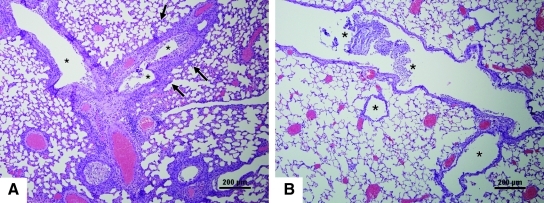

Treatment with anti-IL-6 antibody reduces lung pathology

The substantially higher levels of IL-6 in the BAL fluid, and more severe lung pathology in aerosol- compared to IN-infected mice, is consistent with previous findings that high levels of IL-6 expression are correlated with more severe influenza virus infection in mice and ferrets (7,45). To determine the role of IL-6 in lung pathology and severity of disease, aerosol-inoculated mice were prophylactically treated with anti-IL-6 or isotype control antibody. Antibody treatment had no effect on virus replication as determined by virus titers in the nasal washes and lungs of infected mice at 3 dpi (data not shown). Mean IL-6 levels in treated mice were approximately twofold lower compared to untreated mice, although the difference was not statistically different. However, treatment with anti-IL-6 antibodies dramatically reduced neutrophilic infiltration and lung pathology compared to isotype control antibody-treated mice (Fig. 5). Inflammatory cellular infiltrates filled the bronchioles of untreated mice, and inflammation was also present in the alveolar spaces (Fig. 5A); however, in prophylactically-treated mice, inflammation in the bronchioles was minimal, and there was no inflammation in the surrounding alveoli (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that higher lung IL-6 levels were correlated with more severe disease, and support the notion that lung damage in aerosol-inoculated mice was due to the host immune response and not virus replication.

FIG. 5.

Lung pathology at 3 dpi in aerosol-inoculated untreated or anti-IL-6-treated mice. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained images from an aerosol-inoculated mouse with no treatment (A), or treated with anti-IL-6 antibody (B; scale bars = 200 μm). (A) Inflammatory infiltrates fill a bronchiole (asterisks), and the inflammation is present within the adjacent alveolar spaces and alveolar walls (arrows). (B) After treatment, inflammation in the individual bronchioles is much less intense (asterisks), and the surrounding alveoli and alveolar walls are free of inflammatory exudate. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/vim.

Discussion

It is well established that the route of infection affects the nature of the innate and adaptive immune response; however, little is known about the immune response and disease outcomes after aerosol infection by influenza virus. In natural infections, transmission of influenza likely occurs through aerosols, based on observations consistent with rapid and simultaneous onset of disease in multiple individuals and in nosocomial outbreaks (41). In this study, immune and disease outcomes following two different routes of influenza virus inoculation were evaluated using a sub-lethal mouse-adapted strain of influenza. Aerosol inoculation resulted in a more robust infection and a higher level of pulmonary disease pathogenesis, characterized by a greater extent of inflammatory cell infiltration and granular cell activation compared to IN-inoculated mice. Aerosol inoculation also resulted in increased IL-6 expression in the lung compared to IN inoculation. While IL-6 levels were not significantly altered, treatment with IL-6-blocking antibodies reduced associated pulmonary inflammation and disease. Because the virus-replication kinetics were independent of the method of inoculation, we suggest that the differences in lung pathology observed between aerosol- and IN-inoculated mice may be linked to higher levels of activation of granular cell infiltrates, and possibly IL-6 levels.

It is well established that neutrophilic lung infiltration is associated with the inflammatory response to influenza virus infection. Following influenza infection, neutrophils are recruited to and accumulate in the lungs as early as 8 h post-infection (47). Studies have shown a critical role of neutrophils in containment and clearance of influenza virus, by restricting early virus replication (47,48). In these studies, neutrophil depletion was shown to exacerbate pulmonary inflammation by enhancing virus replication and accelerating disease, as well as altering the pathogenicity of a non-lethal influenza virus. However, increased neutrophil infiltrates have been observed in cases of severe influenza infection in mice, suggesting that these cells may also have a role in acute lung inflammation (8,11,38), and perhaps disease pathogenesis.

Lung pathology associated with severe influenza virus infection has been associated with an excessive innate immune response (28,31). Toll-like receptor signaling pathways are important in innate responses that affect disease outcomes, one example being the recent finding that TRIF-TRAF6 signaling can control the severity of acute lung injury (21). In this study, TLR4-TRIF-TRAF6 pathway signaling in lung macrophages, and the subsequent expression of IL-6, was associated with neutrophil recruitment and activation. The respiratory burst by neutrophils and the expression of reactive oxygen intermediates typically contribute to pathogen control; however, oxygen radical formation also contributes to the pathogenesis. This has been shown in influenza virus studies in which inhibitors of oxygen free radicals improved lung pathology and survival in mice after infection (37). Thus the high levels of activated neutrophils in the BAL fluid of aerosol-inoculated mice shown in this study likely contributed to the observed lung pathology.

Influenza virus infection induces a cascade of proinflammatory cytokines in the lung, including type I interferon (IFN-α/β), TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 (31). Studies of human volunteers have shown a direct correlation between disease severity and levels of these cytokines in nasal wash fluids and plasma (14,18,43). In human volunteers infected with an influenza A H1N1 isolate, increased levels of IL-6 and IFN-α were correlated with illness and the rate of virus replication (18). In animal models of influenza infection, severe infection characterized by increased lung pathology has also been associated with increased levels of IL-6 in nasal wash fluids and sera, particularly at 3 dpi (27,45). In ferrets, IL-6 was only detected in nasal wash samples from animals inoculated with more virulent H1N1 and H3N2 influenza viruses (45). IN infection of mice with a lethal dose of PR8 resulted in an early increase in IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, GM-CSF, and LTB4 in lung fluids, with peak cytokine responses occurring from 36 h to 3 dpi (20). In another mouse study, IL-6 levels were shown to increase over a 6-day period after sub-lethal infection with PR8, and showed an acute and significant elevation following infection with a lethal dose of virus (10). In addition, IL-1α and IL-1β, as well as IL-6 and IFN-γ, have been shown to be elevated in the lungs of mice IN infected with the highly pathogenic H5N1 and 1918 influenza viruses, and significantly higher levels of IL-6 were detected in their lungs compared to mice infected with low-pathogenic isolates (28,29,46). The results reported here suggest that aerosol infection induces predominately a Th-2-type cytokine response. Interestingly, the level of IL-6 was at least sixfold higher in the BAL fluid from aerosol-infected mice than in IN-infected mice (Table 2). These results are consistent with the finding of higher levels of PMNs recruited to the lungs of aerosol-infected mice, and the known interplay between low IFN-γ and high IL-6 expression in PMN recruitment (33). Together, these findings implicate increased IL-6 expression as a biomarker of severe lung pathology.

IFN-γ is a well-known immune regulatory cytokine that drives proinflammatory immune responses and CTL activity; however, several studies have shown that its expression is not essential for influenza clearance (5,17,36,39). For example, mice treated with anti-IFN-γ antibodies showed no significant difference in virus clearance and lung pathology from controls; however, the total number of cells isolated from the lungs of these treated mice was significantly reduced compared to mock-treated animals, suggesting that IFN-γ is important in leukocyte recruitment and retention (5). IFN-γ has been shown to control PMN infiltration during peritoneal inflammation and to modulate IL-6 signaling; IFN-γ-deficient mice had impaired PMN recruitment to the peritoneum and decreased caspase 3 activity (33). In our studies, at 3 dpi, aerosol-inoculated mice had low levels of IFN-γ, high levels of IL-6, and increased PMN numbers in the lung, compared to IN-inoculated mice. Together these findings suggest that the interplay between high IL-6 and low IFN-γ in the lung is important in PMN and inflammatory cell recruitment, as well as granular cell activation and related disease pathogenesis.

The results of this study demonstrate that the route of influenza infection (i.e., topical instillation or aerosol delivery) affects morbidity, mortality, and lung pathology, all features that are linked to lung inflammatory responses. As influenza can be transmitted among humans by inhalation of small airborne particles, and in this study the host responses and disease outcomes were shown to be different in aerosol-inoculated and IN-inoculated mice, this suggests that using aerosol as a route of exposure may facilitate a better understanding of the disease process in humans. The findings of this study also suggest a role for activated neutrophils in influenza virus-induced pathology, and indicate that controlling IL-6 expression may serve as a potential intervention strategy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Georgia Research Alliance, and in part by National Institutes of Health grant no. HHSN266200700006C. The authors would like to thank Dr. Mark Papania at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, and Cheryl Jones for their support and advice.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Alford RH. Kasel JA. Gerone PJ. Knight V. Human influenza resulting from aerosol inhalation. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1966;122:800–804. doi: 10.3181/00379727-122-31255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allan W. Carding SR. Eichelberger M. Doherty PC. hsp65 mRNA+ macrophages and gamma delta T cells in influenza virus-infected mice depleted of the CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte subsets. Microb Pathog. 1993;14:75–84. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allan W. Tabi Z. Cleary A. Doherty PC. Cellular events in the lymph node and lung of mice with influenza. Consequences of depleting CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1990;144:3980–3986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnard DL. Animal models for the study of influenza pathogenesis and therapy. Antiviral Res. 2009;82:A110–A122. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumgarth N. Kelso A. In vivo blockade of gamma interferon affects the influenza virus-induced humoral and the local cellular immune response in lung tissue. J Virol. 1996;70:4411–4418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4411-4418.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belser JA. Wadford DA. Pappas C, et al. Pathogenesis of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) and triple-reassortant swine influenza A (H1) viruses in mice. J Virol. 1996;84:4194–4203. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02742-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brydon EW. Morris SJ. Sweet C. Role of apoptosis and cytokines in influenza virus morbidity. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:837–850. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchweitz JP. Harkema JR. Kaminski NE. Time-dependent airway epithelial and inflammatory cell responses induced by influenza virus A/PR/8/34 in C57BL/6 mice. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:424–435. doi: 10.1080/01926230701302558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carding SR. Allan W. Kyes S. Hayday A. Bottomly K. Doherty PC. Late dominance of the inflammatory process in murine influenza by gamma/delta + T cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1225–1231. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conn CA. McClellan JL. Maassab HF. Smitka CW. Majde JA. Kluger MJ. Cytokines and the acute phase response to influenza virus in mice. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:R78–R84. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.1.R78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng G. Bi J. Kong F, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome induced by H9N2 virus in mice. Arch Virol. 1995;155:187–195. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0560-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dilbeck PM. McElwain TF. Immunohistochemical detection of Coxiella burnetti in formalin-fixed placenta. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1994;6:125–127. doi: 10.1177/104063879400600129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankova V. Inhalatory infection of mice with influenza A0/PR8 virus. I. The site of primary virus replication and its spread in the respiratory tract. Acta Virol. 1975;19:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gentile D. Doyle W. Whiteside T. Fireman P. Hayden FG. Skoner D. Increased interleukin-6 levels in nasal lavage samples following experimental influenza A virus infection. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:604–608. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.5.604-608.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerhard W. Mozdzanowska K. Furchner M. Washko G. Maiese K. Role of the B-cell response in recovery of mice from primary influenza virus infection. Immunol Rev. 1997;159:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Govorkova EA. Kaverin NV. Gubareva LV. Meignier B. Webster RG. Replication of influenza A viruses in a green monkey kidney continuous cell line (Vero) J Infect Dis. 1995;172:250–253. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham MB. Dalton DK. Giltinan D. Braciale VL. Stewart TA. Braciale TJ. Response to influenza infection in mice with a targeted disruption in the interferon gamma gene. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1725–1732. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayden FG. Fritz R. Lobo MC. Alvord W. Strober W. Straus SE. Local and systemic cytokine responses during experimental human influenza A virus infection. Relation to symptom formation and host defense. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:643–649. doi: 10.1172/JCI1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He F. Du Q. Ho Y. Kwang J. Immunohistochemical detection of influenza virus infection in formalin-fixed tissues with anti-H5 monoclonal antibody recognizing FFWTILKP. J Virol Methods. 2009;155:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hennet T. Ziltener HJ. Frei K. Peterhans E. A kinetic study of immune mediators in the lungs of mice infected with influenza A virus. J Immunol. 1992;149:932–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imai Y. Kuba K. Neely GG, et al. Identification of oxidative stress and toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell. 2008;133:235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jefferson T. Foxlee R. Del Mar C, et al. Interventions for the interruption or reduction of the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD006207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006207.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jemski JV. Walker JS. Aerosol vaccination of mice with a live, temperature-sensitive recombinant influenza virus. Infect Immun. 1976;13:818–824. doi: 10.1128/iai.13.3.818-824.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johansson BE. Kilbourne ED. Comparison of intranasal and aerosol infection of mice in assessment of immunity to influenza virus infection. J Virol Methods. 1991;35:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(91)90090-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knight V. Viruses as agents of airborne contagion. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1980;353:147–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb18917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knight V. Aerosol treatment of influenza. Cardiovasc Res Cent Bull. 1981;19:118–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobasa D. Jones SM. Shinya K, et al. Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2007;445:319–323. doi: 10.1038/nature05495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobasa D. Takada A. Shinya K, et al. Enhanced virulence of influenza A viruses with the haemagglutinin of the 1918 pandemic virus. Nature. 2004;431:703–707. doi: 10.1038/nature02951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipatov AS. Andreansky S. Webby RJ, et al. Pathogenesis of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza virus NS gene reassortants in mice: the role of cytokines and B- and T-cell responses. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:1121–1130. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Little JW. Douglas RG Jr. Hall WJ. Roth FK. Attenuated influenza produced by experimental intranasal inoculation. J Med Virol. 1979;3:177–188. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890030303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maines TR. Szretter KJ. Perrone L, et al. Pathogenesis of emerging avian influenza viruses in mammals and the host innate immune response. Immunol Rev. 2008;225:68–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maltezou HC. Nosocomial influenza: new concepts and practice. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:337–343. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283013945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLoughlin RM. Witowski J. Robson RL, et al. Interplay between IFN-gamma and IL-6 signaling governs neutrophil trafficking and apoptosis during acute inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:598–607. doi: 10.1172/JCI17129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mount AM. Belz GT. Mouse models of viral infection: influenza infection in the lung. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;595:299–318. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-421-0_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mozdzanowska K. Maiese K. Gerhard W. Th cell-deficient mice control influenza virus infection more effectively than Th- and B cell-deficient mice: evidence for a Th-independent contribution by B cells to virus clearance. J Immunol. 2000;164:2635–2643. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen HH. van Ginkel FW. Vu HL. Novak MJ. McGhee JR. Mestecky J. Gamma interferon is not required for mucosal cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses or heterosubtypic immunity to influenza A virus infection in mice. J Virol. 2000;74:5495–5501. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.12.5495-5501.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oda T. Akaike T. Hamamoto T. Suzuki F. Hirano T. Maeda H. Oxygen radicals in influenza-induced pathogenesis and treatment with pyran polymer-conjugated SOD. Science. 1989;244:974–976. doi: 10.1126/science.2543070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perrone LA. Plowden JK. Garcia-Sastre A. Katz JM. Tumpey TM. H5N1 and 1918 pandemic influenza virus infection results in early and excessive infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils in the lungs of mice. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000115. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price GE. Gaszewska-Mastarlarz A. Moskophidis D. The role of alpha/beta and gamma interferons in development of immunity to influenza A virus in mice. J Virol. 2000;74:3996–4003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.3996-4003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reed LJ. Meunch H. A simple method for estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hygiene. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salgado CD. Farr BM. Hall KK. Hayden FG. Influenza in the acute hospital setting. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott GH. Sydiskis RJ. Responses of mice immunized with influenza virus by serosol and parenteral routes. Infect Immun. 1976;13:696–703. doi: 10.1128/iai.13.3.696-703.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skoner DP. Gentile DA. Patel A. Doyle WJ. Evidence for cytokine mediation of disease expression in adults experimentally infected with influenza A virus. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:10–14. doi: 10.1086/314823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snyder MH. Stephenson EH. Young H, et al. Infectivity and antigenicity of live avian-human influenza A reassortant virus: comparison of intranasal and aerosol routes in squirrel monkeys. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:709–711. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Svitek N. Rudd PA. Obojes K. Pillet S. von Messling V. Severe seasonal influenza in ferrets correlates with reduced interferon and increased IL-6 induction. Virology. 2008;376:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szretter KJ. Gangappa S. Lu X, et al. Role of host cytokine responses in the pathogenesis of avian H5N1 influenza viruses in mice. J Virol. 2007;81:2736–2744. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02336-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tate MD. Brooks AG. Reading PC. The role of neutrophils in the upper and lower respiratory tract during influenza virus infection of mice. Respir Res. 2008;9:57. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tate MD. Deng YM. Jones JE. Anderson GP. Brooks AG. Reading PC. Neutrophils ameliorate lung injury and the development of severe disease during influenza infection. J Immunol. 2009;183:7441–7450. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tellier R. Review of aerosol transmission of influenza A virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1657–1662. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson WW. Shay DK. Weintraub E. Brammer L. Bridges CB. Cox NJ. Fukuda K. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333–1340. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson WW. Shay DK. Weintraub E. Brammer L. Cox N. Anderson LJ. Fukuda K. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tripp RA. Tompkins SM. Animal models for evaluation of influenza vaccines. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;333:397–412. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-92165-3_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turner SJ. Kedzierska K. La Gruta NL. Webby R. Doherty PC. Characterization of CD8+ T cell repertoire diversity and persistence in the influenza A virus model of localized, transient infection. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Laan JW. Herberts C. Lambkin-Williams R. Boyers A. Mann AJ. Oxford J. Animal models in influenza vaccine testing. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7:783–793. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.6.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Webster RG. Laver WG. Kilbourne ED. Reactions of antibodies with surface antigens of influenza virus. J Gen Virol. 1968;3:315–326. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-3-3-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]