Abstract

Infected cardiac myxoma is a rare cause of endocarditis. The finding of coexisting infected cardiac myxomas is highly unusual. Herein, we present the case of a 58-year-old woman with a low-grade fever. Laboratory findings strongly indicated inflammation, and blood cultures detected Staphylococcus species. Echocardiograms revealed mobile masses in the area of the mitral valve. Transesophageal echocardiograms showed 2 formations that arose from opposite sides of the mitral annulus and protruded into the left ventricle during systole. During emergency surgery, 2 abnormal growths with numerous vegetations were completely excised. The diagnosis of myxoma was confirmed upon histologic evaluation. Microbiological and polymerase chain reaction analysis of the myxomas detected the bacterial strain Enterococcus faecalis. Five months postoperatively, the patient showed no signs of recurrent infection and had a normal echocardiographic appearance.

This report is the first of an infected cardiac myxoma in the Czech population and one of approximately 60 reports in the medical literature from 1956 to the present. In addition to the case of our patient, we discuss the discrepancy between the bacteriologic findings.

Key words: Bacteroidaceaeinfections/complications/diagnosis/drug therapy; echocardiography; heart atria/pathology; heart neoplasms/diagnosis/surgery; heart valve diseases/surgery; myxoma/diagnosis/pathology/surgery; neoplasms, second primary; treatment outcome

Cardiac myxoma is a rare tumor. In a very few cases, this benign neoplasm becomes infected, manifesting itself with symptoms of fever or with sepsis of unclear origin. The discovery of 2 infected cardiac myxomas in 1 patient is highly unusual. Herein, we discuss the case and surgical treatment of our patient with this condition.

Case Report

In April 2009, a 58-year-old woman presented at our hospital with a low-grade fever and no chest pain. Three weeks earlier, she had been given antibiotic therapy for inflammation of the Achilles tendon. Upon her examination in the department of infectious disease, laboratory findings strongly indicated inflammation. Blood cultures detected a plasma coagulase-negative strain of Staphylococcus species. The patient was admitted to the hospital, and targeted therapy with antibiotics was initiated. Echocardiograms showed 2 mobile, lobe-shaped growths in the left ventricle (LV) in the region of the mitral valve. Peripheral embolism was not found. The patient was transferred to the department of cardiac surgery because of suspected mitral valve endocarditis.

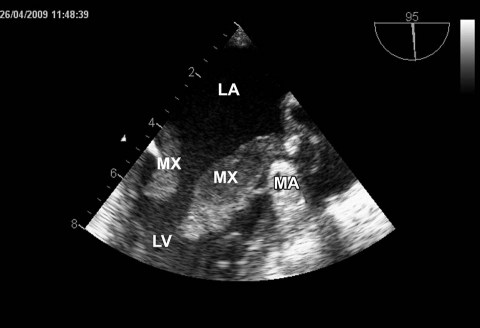

Upon transfer, the patient still had a low-grade fever. Chest and lung radiographs showed a cardiac silhouette of normal size, adequate pulmonary markings, and no focal lesions. An electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia (heart rate, 100 beats/min) and no myocardial ischemia. Laboratory investigations revealed leukocytosis (total leukocytes, 16.6 ×109/L) and elevated levels of C-reactive protein (187 mg/L) and procalcitonin (1.76 μg/L). Computed tomography ruled out an extracardiac origin of the growths in the LV. Transesophageal echocardiography confirmed that 2 masses arose from opposite sides of the mitral annulus and protruded into the LV during diastole (Fig. 1). No other abnormal structures were seen in the cardiac chambers. The mitral valve showed no signs of destruction or perforation; there was mild mitral regurgitation, no annular dilation, and no lesion on the aortic valve. Overall LV systolic function was good (ejection fraction, >0.60). Because the patient had no cardiac history and showed no signs of myocardial ischemia, coronary angiography was not performed. Blood cultures obtained preoperatively in our center had been negative for bacteria.

Fig. 1 Transesophageal echocardiography shows 2 formations that arise from opposite sides of the mitral annulus (MA) and protrude into the left ventricle (LV) during diastole.

LA = left atrium; MX = myxoma

The diagnosis of left atrial myxoma was made, and emergent on-pump surgery was performed. An aortic cannula and 2 venous cannulae were inserted into both caval veins. The aorta was cross-clamped, and cold-blood cardioplegic solution was injected into the aortic root. Visual inspection of the mitral valve through a surgical opening in the left atrium revealed 2 growths. The 1st myxoma (size, approximately 1 × 2 cm) arose from an area close to the mitral annulus, not far from the posteromedial commissure. The other myxoma (size, 6 × 1 cm) originated from the margin of the left atrial appendage. Numerous brittle vegetations with a high potential for embolism were seen at the distal ends of both formations. Both abnormal structures were completely removed. The left atrium was sutured, extracorporeal circulation was terminated uneventfully, and the operation was completed upon the suturing of the surgical wound. The total time that the patient was on cardiopulmonary bypass was 50 min, with 40 min of cross-clamping. She was hemodynamically stable without pharmacologic support and was extubated later on the day of surgery.

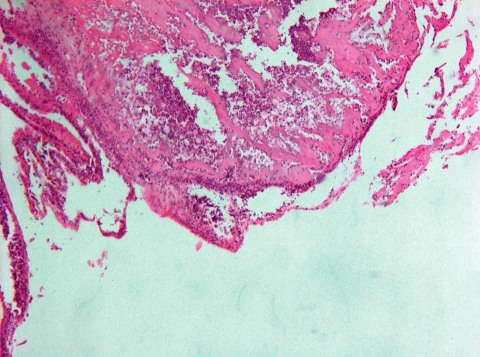

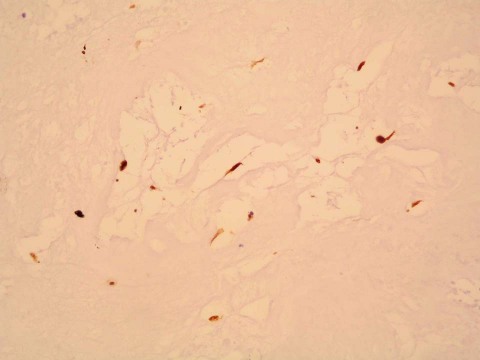

The patient's postoperative course was uneventful, the blood cultures were negative for bacteria, and the low-grade fever disappeared. She was given antibiotic therapy because of the postoperative microbiological finding of Enterococcus faecalis in the myxomatous tissue. This finding was further confirmed by means of microbial DNA analysis using polymerase chain reaction. Histologic results confirmed the diagnosis of myxoma with extensive surface vegetations (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2 Photomicrograph shows myxomatous tissue with endocarditis-related vegetation and thrombus composed of fibrin with neutrophils and macrophages (H & E, orig. ×50).

Fig. 3 Photomicrograph is positive for calretinin in the myxomatous cells (H & E, orig. ×200).

The patient was transferred to the cardiology department on postoperative day 14 to continue receiving parenteral antibiotic therapy. She was discharged from the hospital 3 days thereafter. Upon follow-up examinations 5 months and 1 year postoperatively, she had completely recovered and was afebrile.

Discussion

Approximately half of all cardiac neoplasms are myxomas. In sporadic (nonfamilial) form, myxomas develop more often in women than in men. Whereas 75% of myxomas are found in the left atrium and 20% are found in the right atrium, 3% to 5% of myxomas grow in the cardiac ventricles.1,2 The tumor is benign, with a potential for recurrence in about 3% of cases.3 The likelihood of recurrence is higher in some types of hereditary myxomas, which, along with other manifestations, are part of a syndrome called Carney complex. First described in 1985, Carney complex is a clinical syndrome of multiple cardiac and noncardiac myxomas, abnormal skin pigmentation, endocrine abnormalities, and neural disease (schwannoma). Multicentric myxomas are associated with the syndrome of hereditary myxoma, so the finding of 2 sporadic myxomas in 1 patient is atypical.3–5

Symptoms of myxoma vary and often can be mistaken for symptoms of other conditions. The most common systemic symptoms include fatigability, joint pain, weight loss, and low-grade fever. Myxoma can mimic mitral annular obstruction or lead to mitral regurgitation, thus producing symptoms such as dyspnea, syncope, angina pectoris, peripheral embolism, and heart failure.1,2,6,7 The optimal diagnostic methods by which to identify cardiac myxomas are transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography; however, the mediastinum and the paracardiac spaces are best examined by means of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging.8

Low-grade fever that accompanies myxoma does not necessarily mean that the neoplasm is infected. According to Revankar and Clark,9 myxoma is infected when bacteria are present in myxomatous tissue as confirmed by histologic results, or when blood cultures are positive and signs of inflammation are seen in the histologic specimen. In our patient, histologic examination did not reveal bacteria; however, the myxomatous tissue showed endocarditis-related vegetation and a thrombus composed of fibrin with neutrophils and macrophages, and the finding was confirmed by use of polymerase chain reaction. Hence, the diagnosis of infected myxoma was not in doubt.

This is the 1st report of infected myxoma in the Czech population. Since infected cardiac myxoma was first reported in 1956,10 fewer than 60 reports have been published—an indication that the condition is indeed very rare.9 Infected cardiac myxoma with coexisting valvular endocarditis has also been reported.11

Of note in our case is the discrepancy between the results of the initial blood culture (detection of Staphylococcus species) and the final finding of a different infectious agent (E. faecalis) in the myxomatous tissue. The Staphylococcus species may have been residual infection of the patient's Achilles tendon or contamination from the skin, and the failure to detect the enterococcus in the preoperative blood culture may have been due to the patient's prior antimicrobial therapy.

Enterococcus faecalis is the 3rd most common cause of infected myxomas (after Streptococcus species and Staphylococcus species).9 Infection of myxomas can be preceded by dental procedures and untreated caries, illegal-drug abuse, invasive procedures, prolonged corticosteroid use, and (as in our patient's case) recent infection.12 Because fever is associated with myriad diseases, the possible diagnosis of cardiac myxoma might be overlooked. Accordingly, a patient with fever of unknown origin should undergo transthoracic or transesophageal echocardiography—methods that detect myxomas with 100% sensitivity.9

The treatment for cardiac myxoma is complete surgical resection. Patients with growths that impede the circulation (as in blockage of the mitral annulus) should undergo surgery as soon as possible. Myxomas are very friable and have a high potential for embolism. Therefore, early resection is equally crucial in regard to asymptomatic myxomas, whether infected or uninfected. Regardless of infection, myxomas embolize with a similar incidence of approximately 20%.9 Intraoperatively, manipulation of the heart before clamping should be avoided.

When infected myxoma is diagnosed in time and removed without delay, it is an easily treatable disease with excellent patient outcomes.9,13 Our patient recovered completely and without sequelae.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Marek Adamira, MD, Department of Cardiology, Institute for Clinical & Experimental Medicine (IKEM), Videnska 1958/9, 140 21 Prague 4, Czech Republic. E-mail: marek.adamira@ikem.cz

References

- 1.Schaff HV, Mullany CJ. Surgery for cardiac myxomas. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000;12(2):77–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Tillmanns H. Clinical aspects of cardiac tumors. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1990;38 Suppl 2:152–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Shinfeld A, Katsumata T, Westaby S. Recurrent cardiac myxoma: seeding or multifocal disease? Ann Thorac Surg 1998; 66(1):285–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Mahilmaran A, Seshadri M, Nayar PG, Sudarsana G, Abraham KA. Familial cardiac myxoma: Carney's complex. Tex Heart Inst J 2003;30(1):80–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Carney JA. Differences between nonfamilial and familial cardiac myxoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1985;9(1):53–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Zaviacic L, Zaviacic L. Left atrial myxoma. Cor et Vasa 2007; 49(7–8):250–3.

- 7.Janion M, Sielski J, Ciuraszkiewicz K. Sepsis complicating giant cardiac myxoma. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26(3):387:e3–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Puvaneswary M, Thomson D. Magnetic resonance imaging features of an infected right atrial myxoma. Australas Radiol 2001;45(4):501–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Revankar SG, Clark RA. Infected cardiac myxoma. Case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 1998;77(5):337–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Dick HJ, Mullin EW. Myxoma of the heart complicated by bloodstream infection by Staphylococcus aureus and Candida parapsilosis. N Y State J Med 1956;56(6):856–9. [PubMed]

- 11.Vogt PR, Jenni R, Turina MI. Infected left atrial myxoma with concomitant mitral valve endocarditis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1996;10(1):71–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Garcia-Quintana A, Martin-Lorenzo P, Suarez de Lezo J, Diaz-Escofet M, Llorens R, Medina A. Infected left atrial myxoma [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Cardiol 2005;58(11):1358–60. [PubMed]

- 13.Riad MG, Parks JD, Murphy PB, Thangathurai D. Infected atrial myxoma presenting with septic shock. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2005;19(4):508–11. [DOI] [PubMed]