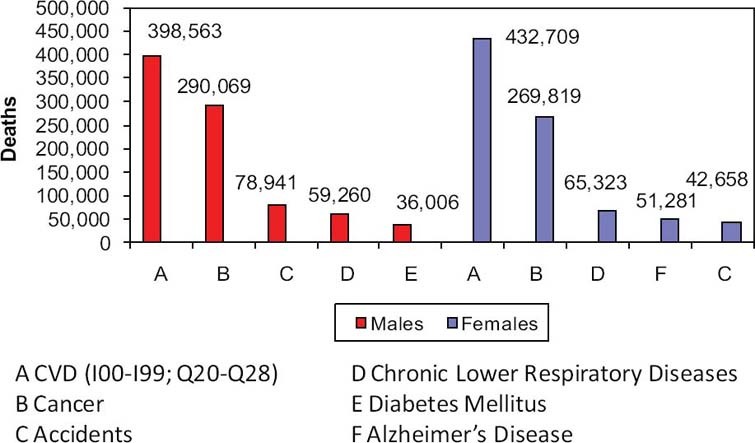

Cardiovascular disease (CVD)—the leading cause of death in both men and women among all racial and ethnic groups in the United States—resulted in 631,636 deaths in 2006.1 It remains the number-one threat to women's health in the developing world (Fig. 1). More women than men die each year of CVD. In 2006, the number of deaths attributed to CVD was approximately 432,700 in women and 398,600 in men. The lifetime risk of a woman's developing CVD by age 50 is an estimated 39%.2

Fig. 1 Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and other major causes of death for men and women in the United States (2006).

Sources: National Center for Health Statistics. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Although not curable, CVD is largely preventable. Modification of 9 easily measured clinical and laboratory risk factors can prevent up to 90% of first myocardial infarctions.3 The long-recognized risk factors include age, sex, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, smoking status, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and a sedentary lifestyle. In addition, chronic kidney disease and insulin resistance (pre-diabetes) can be important risk factors for CVD.

Modifying the more common risk factors associated with heart disease through lifestyle changes (quitting smoking and increasing physical activity) or the use of medications (lowering blood pressure and reducing cholesterol levels) has decreased death associated with CVD in women by 23% since 2000.4 Tobacco use in women has decreased by an absolute 3.6% (from 23% to 19.7%) since 2000, and 3% more women report regular physical activity. In addition, death from stroke has decreased significantly since 1998. This is largely attributable to improved medical therapies for hypertension—the risk factor that contributes to more CVD deaths in women than does any other modifiable cardiac risk factor.5 Great strides also have been made in reducing cholesterol levels in women, through both primary and secondary CVD-prevention strategies. Statin use from 2000 through 2010 has increased from 1.9% to 13.5% in women aged 45 to 65 years and from 3.5% to 32.8% in women aged >65 years. Unfortunately, statin use in women still lags behind that of men.4

The prevalence of other modifiable cardiac risk factors among women has increased in the past decade. Obesity and diabetes rates are increasing and show a marked variation by race or ethnicity. According to 2006 statistics from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 31.3% of white women, 53.2% of black women, and 41.8% of Mexican-American women are obese (body mass index, ≥30 kg/m2), which corresponds to a gradient in the incidence of diabetes of 8.2% in white women, 15.3% in black women, and 16.9% in Mexican-American women.

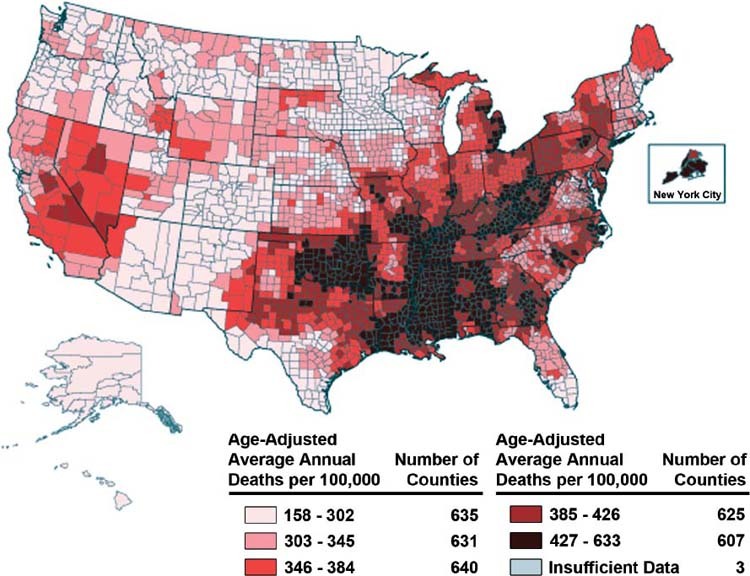

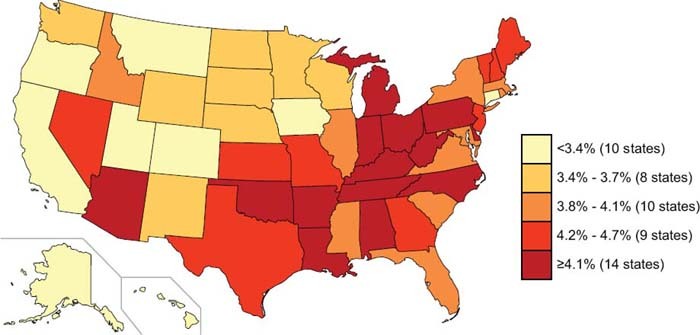

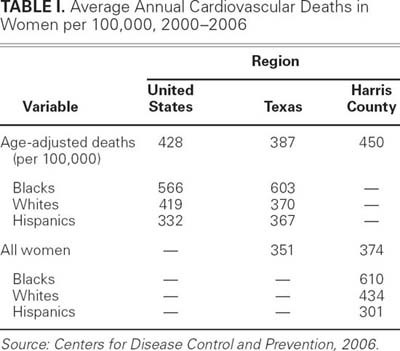

In June 2010, statistics from the CDC showed significant geographic variation in death rates due to CVD, according to county (Fig. 2). Residents in the southeastern U.S. were at highest risk for CVD. Overall, rates of obesity, poverty, and hypertension mirror the geographic distribution of CVD death (Fig. 3). We investigated the age-adjusted CVD mortality rate for women in Texas and in Harris County (the second most populous county in the U.S., Harris has a population that exceeds the populations of 23 states) and found a much higher CVD mortality rate than in the United States at large during this same period (Table I).6 The racial disparity was striking. Cardiovascular death was greatest for black women (566 CVD deaths per 100,000 in the U.S., 603 per 100,000 in Texas, and 610 per 100,000 in Harris County) and lowest for Hispanic women (332 CVD deaths per 100,000 in the U.S., 367 per 100,000 in Texas, and 301 per 100,000 in Harris County). White women had intermediate outcomes (419 CVD deaths per 100,000 in the U.S., 370 per 100,000 in Texas, and 434 per 100,000 in Harris County). For black women in Harris County, CVD death was 41% greater than for white women and 100% greater than for Hispanic women—an intriguing finding, since the burden of disease in a given group should be proportional to the underlying cardiovascular risk factor burden for that group. Women of a lower socioeconomic status and education level and those with little access to medical care have been shown to have an increased risk for CVD. Hispanic women more frequently have biologic risk factors such as obesity and diabetes than do white women, but the rates of obesity and hypertension among Hispanic women are lower than in black women. Therefore, a greater magnitude of, earlier exposure to, and longer duration of hypertension in black women may contribute to their increased CVD mortality rate.

Fig. 2 Average annual heart disease death rates by county in all adult women aged 35 years and older (2000–2006).

Sources: National Vital Statistics System and the U.S. Census Bureau.

Fig. 3 Coronary heart disease and stroke trends by state (2007).

Sources: Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention: Data Trends & Maps Web site. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

TABLE I. Average Annual Cardiovascular Deaths in Women per 100,000, 2000–2006

Socioeconomic status has been shown to have a significant effect on rates of hypertension, obesity, and diabetes. For women living just below the poverty level, rates of obesity have increased only slightly (by 0.3%) in the past decade. However, in those with income levels at 100% to 199% of the poverty level, obesity rates have increased 1.8%; in those with income levels at greater than 200% of the poverty level, obesity rates have increased by 3.6%.4 Brown and O'Connor4 describe this as the “dose-response relationship between obesity and income,” and there probably is a corresponding influence on the rates of hypertension, which also vary by income level.

The best treatment for CVD is prevention. Identification and modification of clinical and metabolic risk factors has dramatically reduced the mortality rates in women in association with stroke, myocardial infarction, and coronary heart disease. Although the disparities in CVD mortality rates between men and women are declining, ethnic and racial disparities persist.7 Geographic increases in the rates of obesity and diabetes in women threaten to erode 2 decades of decline in CVD mortality rates. Healthier communities begin with education and with encouraging women to incorporate CVD-prevention strategies into their everyday lives.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Stephanie A. Coulter, MD, 6720 Bertner Ave., Houston, TX 77030. E-mail: scoulter@texasheart.org

Presented at the Risk, Diagnosis and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease in Women symposium; Denton A. Cooley Auditorium, Texas Heart Institute, Houston; 11 September 2010.

References

- 1.Heron M, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B; Division of Vital Statistics. Deaths: final data for 2006 [report on the Internet]. National Vital Statistics Reports Vol. 57, No. 14. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics, 2009 Apr 17 [cited 2011 Feb 3]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr57/nvsr57_14.pdf. [PubMed]

- 2.D'Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117(6):743–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 2004;364(9438):937–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Brown JR, O'Connor GT. Coronary heart disease and prevention in the United States. N Engl J Med 2010;362(23):2150–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee [published errata appear in Circulation 2009;119 (3):e182 and Circulation 2010;122(1):e11]. Circulation 2009; 119(3):e21–181. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart disease & stroke maps [report on the Internet; cited 2011 Feb 3]. Available from: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/giscvh2/Default.aspx.

- 7.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation 2005;111(10):1233–41. [DOI] [PubMed]