Abstract

Fifty-six serum posaconazole trough levels were measured in 17 cardiothoracic transplant recipients. Initial levels were ≤0.5, 0.51 to 0.99, and ≥1 μg/ml for 47, 29, and 24% of patients, respectively. Median trough levels associated with therapeutic success were higher than those associated with failure (1.55 versus 0.34 μg/ml; P = 0.006). Patients with levels consistently >0.5 μg/ml were more likely to have successful outcome (P = 0.055). Age ≥65 years, oral administration, and absence of proton pump inhibitors were associated with higher levels of posaconazole (P = 0.006, 0.006, and 0.001, respectively).

Posaconazole is a new triazole antifungal agent that has broad activity against pathogenic fungi, making it an attractive option for the treatment and prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections (IFIs). Currently, posaconazole is approved for prophylaxis in hematopoietic stem-cell transplant (HSCT) recipients (12). In this population, significant exposure-response relationships have been documented (7). Solid-organ transplant (SOT) recipients, in particular lung transplant recipients, are also at an increased risk for the development of IFIs (14). There is less experience, however, with posaconazole usage among SOT recipients than HSCT recipients. The objectives of this study were to describe the results of posaconazole therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) among cardiothoracic transplant recipients at our center, correlate serum posaconazole trough levels with response to therapy, and identify factors that impacted levels.

Between January 2008 and July 2010, a total of 56 serum posaconazole trough levels from 17 cardiothoracic transplant patients, as measured by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), were available for analysis (Table 1). Six patients had a single level measured, and 11 had multiple levels measured (median = 5). No patients received rifampin, phenytoin, or carbamazepine. The most common initial posaconazole dosage was 200 mg three times daily (53%; 9/17 patients), followed by 200 mg four times daily (24%; 4/17 patients) and 400 mg twice daily (24%; 4/17 patients). The median time from the start of therapy to the first level was 20.5 days. The initial posaconazole levels were ≤0.50 μg/ml for 47% (8/17) of patients, 0.51 to 0.99 μg/ml for 29% (5/17) of patients, and ≥1.0 μg/ml for 24% (4/17) of patients.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive data of patients receiving posaconazole

| Patient no. | Age (yr)/sexa | Underlying disease | Indicationb | Posaconazole level (μg/ml) |

Dose adjustment based on level | Outcome | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Median (range) | |||||||

| 1 | 55/F | Lung transplant | Primary prophylaxis (voriconazole intolerance) | 0.14 | 0.14 | No | Failure | Breakthrough Aspergillus colonization |

| 2 | 43/M | Lung transplant | Primary prophylaxis (voriconazole intolerance) | 0.81 | 0.22 (≤0.1-0.81) | Yes | Failure | Breakthrough Aspergillus colonization |

| 3 | 48/F | Lung transplant | Secondary prophylaxis (A. terreus and voriconazole intolerance) | 0.25 | 0.25 (≤0.1-0.95) | Yes | Failure | Persistent A. terreus colonization |

| 4 | 72/M | Lung transplant | Secondary prophylaxis (Rhizomucor) | 1.10 | 0.88 (0.69-1.1) | No | Failure | Breakthrough Aspergillus tracheobronchitis |

| 5 | 65/F | Lung transplant | Secondary prophylaxis (Rhizomucor) | 1.52 | 1.55 (1.52-1.57) | No | Success | |

| 6 | 62/M | Lung transplant | Primary prophylaxis (voriconazole intolerance) | 0.35 | 0.35 | No | Failure | Breakthrough Aspergillus colonization |

| 7 | 27/M | Lung transplant | Primary prophylaxis (voriconazole intolerance) | 0.32 | 0.32 | No | Failure | Discontinuation due to hepatotoxicity |

| 8 | 58/M | Lung transplant | Secondary prophylaxis (Syncephalastrum) | 0.85 | 0.76 (0.66-0.85) | No | Failure | Breakthrough Aspergillus colonization |

| 9 | 62/F | Lung transplant | Secondary prophylaxis (Scedosporium) | 0.58 | 0.66 (0.58-0.74) | No | Success | |

| 10 | 53/M | Lung transplant | Secondary prophylaxis (Rhizomucor- donor) | 1.10 | 1.10 | No | Failure | Breakthrough Aspergillus colonization |

| 11 | 45/F | Lung transplant | Secondary prophylaxis (A. fumigatus) | 0.66 | 0.50 (0.5-0.66) | Yes | Failure | Discontinuation due to hepatotoxicity |

| 12 | 57/M | Lung transplant | Primary therapy for proven Wangiella skin nodules | 0.40 | 0.40 | No | Failure | Recurrent Wangiella infection |

| 13 | 71/M | Heart transplant | Primary therapy for proven Rhizomucor soft tissue infection | 2.54 | 2.54 | No | Success | Underwent adjunctive surgical debridement |

| 14 | 56/M | Lung transplant | Primary therapy for possible IPAc | 0.58 | 0.41 (≤0.1-0.8) | Yes | Failure | Death due to persistent aspergillosis |

| 15 | 70/F | Lung transplant | Primary therapy for possible IPA | 0.50 | 0.64 4 (0.5-1.07) | Yes | Failure | Discontinuation due to hepatotoxicity |

| 16 | 57/M | Lung transplant | Stepdown therapy for proven Rhizomucor tracheobronchitisd | 0.21 | 0.30 (0.18-1.04) | Yes | Failure | Relapse 1 mo after discontinuation |

| 17 | 60/F | Lung transplant | Primary therapy for proven Wangiella tracheobronchitis and probable Wangiella pulmonary infection | 0.34 | 0.24 (≤0.1-0.65) | Yes | Failure | Persistent Wangiella infection |

F, female; M, male.

Primary prophylaxis was used immediately after transplant to prevent fungal infections according to standard practice guidelines at our institution. Secondary prophylaxis is defined as prophylaxis to prevent recurrence or relapse of IFI in patients with previous IFI.

IPA, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Posaconazole was used as step-down therapy, after the acute infection was treated with a lipid formulation of amphotericin B.

Posaconazole was used to treat IFIs in 6 patients and as prophylaxis in 11 patients (Table 1). Three patients had posaconazole discontinued due to hepatotoxicity (Table 1); their levels were not considered in assessing correlations with outcome. For the remaining 14 patients, therapeutic failure was defined according to the Mycosis Study Group and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (MSG/EORTC) consensus criteria (15). In addition, patients who developed a breakthrough fungal infection during posaconazole prophylaxis were also classified as showing therapeutic failure (4). The median posaconazole trough level in patients who were successfully treated (1.55 ± 0.78 μg/ml) was higher than the level in patients who failed therapy (0.34 ± 0.37 μg/ml; P = 0.006). Overall, 50% (3/6) of patients with levels consistently >0.5 μg/ml had therapeutic success, whereas 100% (8/8) of patients who did not maintain levels >0.5 μg/ml failed therapy (P = 0.055).

To evaluate factors that influenced posaconazole levels, we first assessed the impact of patient characteristics such as age, sex, weight, and race on the initial serum trough concentrations from all 17 patients. The median trough level was significantly higher for patients who were ≥65 years old and not overweight, but did not significantly differ by sex or race (Table 2). Age ≥65 years was the only factor associated with a significantly higher initial trough by multiple regression analysis (P = 0.006) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Impact of patient characteristics on initial posaconazole trough levels

| Patient factor | Posaconazole concn (μg/ml) with factor: |

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | ||

| Age ≥65 years | |||

| Median | 1.31 | 0.40 | 0.02 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.42 ± 0.86 | 0.51 ± 0.28 | |

| Male sex | |||

| Median | 0.81 | 0.54 | |

| Mean ± SD | 0.8 ± 0.72 | 0.8 ± 0.43 | NS (0.18) |

| Overweightb | |||

| Median | 0.43 | 0.66 | |

| Mean ± SD | 0.46 ± 0.22 | 0.86 ± 0.70 | 0.04 |

| Caucasian | |||

| Median | 0.58 | 0.50 | |

| Mean ± SD | 0.75 ± 0.63 | 0.50 ± 0.23 | NS (0.41) |

Mann-Whitney test. Note that when using variables with a P value of <0.20, we identified age ≥65 years to be associated with significantly higher initial trough levels by multiple regression analysis (P = 0.006). Weight (P = 0.12) and sex (P = 0.24) were not significantly associated (NS).

As defined by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria (http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/defining.html) (e.g., ≥169 pounds for a person who is 69 in. tall).

Although therapeutic targets for posaconazole have not been defined, tentative recommendations suggest targeting a trough level greater than 0.5 μg/ml for both treatment and prophylaxis (1). At our center, the general practice in response to posaconazole troughs ≤0.5 μg/ml is to encourage oral administration in conjunction with a high-fat meal (rather than feeding tube administration). If this approach is already being taken or trough levels do not improve, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 antagonists are commonly discontinued in a stepwise fashion. To assess the impact of this approach, we evaluated modifiable factors such as route of posaconazole administration and receipt of concomitant H2 antagonists or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs); in this analysis, we included all serum trough levels. Indeed, median serum trough levels were significantly higher in patients taking posaconazole orally and those not taking a concomitant PPI (Table 3). These factors also were found to be independently associated with higher troughs by multiple regression analysis (P = 0.006 and P = 0.001, respectively) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Impact of modifiable factors on posaconazole trough levels

| Treatment factor | Posaconazole concn (μg/ml) with factor: |

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | ||

| Oral administration | |||

| Median | 0.63 | 0.32 | 0.01 |

| Mean ± SD | 0.57 ± 0.49 | 0.37 ± 0.27 | |

| Concomitant H2 antagonist | |||

| Median | 0.50 | 0.50 | NS (0.6) |

| Mean ± SD | 0.75 ± 0.66 | 0.48 ± 0.30 | |

| Concomitant PPI | |||

| Median | 0.40 | 0.64 | 0.02 |

| Mean ± SD | 0.44 ± 0.30 | 0.77 ± 0.60 | |

Mann-Whitney test. Note that when using variables with a P value of <0.20, oral administration and lack of concomitant protein pump inhibitors (PPI) were associated with significantly higher levels by multiple regression analysis (P = 0.006 and 0.001, respectively). NS, not significant.

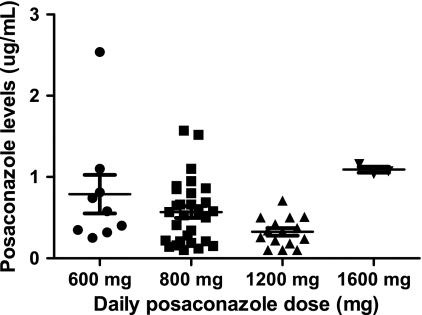

For seven patients, providers elected to treat with 1,200 mg of posaconazole daily, a dosage that is higher than currently recommended. In three patients, the dosage was subsequently increased to 1,600 mg daily. In each of the seven patients, higher-than-recommended doses were prescribed in response to serum trough levels that were felt to be suboptimal despite the interventions described above. Overall, there was no significant difference in median trough levels among patients treated with 600, 800, and 1,200 mg of posaconazole daily (Fig. 1). Administration of 1,600 mg daily, on the other hand, consistently yielded levels ≥1 μg/ml. Side effects were observed in all patients receiving 1,600 mg/day, including elevated hepatic enzymes, gastrointestinal toxicity (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea), and somnolence (67%; 2/3 patients for each type of toxicity).

FIG. 1.

Association between the cumulative daily dose of posaconazole and corresponding serum trough levels.

Taken together, our data highlight several clinical aspects of posaconazole usage that are unique to lung and heart transplant recipients. While some of our findings are consistent with previous reports in HSCT populations, our experience draws attention to important ways in which cardiothoracic transplant recipients differ. The median trough posaconazole level among our patients (0.50 μg/ml) was similar to levels described among HSCT recipients, as was the percentage of patients who did not achieve levels >0.5 μg/ml (9, 10, 17). At the same time, however, factors that classically impact the absorption of posaconazole in HSCT recipients, such as mucositis, acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and chronic diarrhea, were not relevant in our patients (9, 10, 18). Rather, lower serum levels of posaconazole were correlated by multivariate analysis with concomitant receipt of PPI and higher levels with increased age and oral rather than tube feed administration.

The importance of PPI administration, age, and oral dosing is consistent with several distinctive characteristics of cardiothoracic transplant recipients, in particular lung transplant recipients. First, the incidence of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) after lung transplantation is as high as 54%, likely as a result of esophageal or vagal nerve injury during surgery (2). Since GER predisposes patients to microaspiration of bile acids that might lead to allograft injury, most of our lung transplant patients were placed on a PPI. Indeed, 64% (36/56) of posaconazole levels were measured during PPI therapy. Our results are consistent with the observation that the administration of a PPI decreases the mean posaconazole area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) by 32% (11). Second, malnutrition occurs in as many as 61% of lung transplant recipients (3), a phenomenon that can be compounded by a high incidence of gastrointestinal (GI) side effects from immunosuppressive drugs like mycophenolic acid. As such, feeding tube placement to maintain adequate caloric intake after lung transplantation is common. Again, our findings are consistent with previous data that nasogastric tube administration of posaconazole resulted in maximum concentration of drug in serum (Cmax) and AUC values that were only 80% of those observed after oral administration (6). Third, lung transplantation is increasingly offered to older patients. Indeed, almost half of lung transplants at our center in 2009 were performed in patients ≥65 years of age (16), a trend that has accelerated over the past decade. Each patient ≥65 years old in this study consistently exhibited posaconazole levels ≥0.50 μg/ml, an observation that may reflect, at least in part, smaller volumes of distribution (8). Along similar lines, allogeneic HSCT recipients >45 years old had 11% higher average posaconazole concentrations than patients 18 to 45 years of age (10).

Patients who were overweight had a lower median initial posaconazole level than patients who were not overweight, but the significance was lost upon multiple regression analysis (P = 0.12). A similar observation was made in HSCT recipients, where the median posaconazole concentration decreased from 1,128 ng/ml to 879 ng/ml to 814 ng/ml in patients weighing <65, 65 to 80, and >80 kg, respectively (10). Although pharmacokinetic data are limited, posaconazole appears to have a volume of distribution ranging from 5 to 25 liters/kg, which would suggest extensive extravascular distribution (13). The impact of body weight on posaconazole concentrations deserves further investigation.

Identification of a putative cutoff value for adequate posaconazole serum concentrations has proven to be a challenge due to marked inter- and intrapatient variability (13). Recently, a trough level of >0.5 μg/ml was proposed based on evidence generated from the HSCT population (1). Likewise, current understanding of the posaconazole exposure-response relationship is based upon data derived almost exclusively from HSCT recipients (7, 10, 17). To our knowledge, this is the first report to focus on SOT patients receiving posaconazole. Despite our small sample, our findings suggest that a similar cutoff may be applicable. In fact, no patient in our analysis had a positive clinical outcome if posaconazole levels were not consistently >0.5 μg/ml during therapy. In comparison, 50% (3/6) of patients who maintained levels >0.5 μg/ml had a positive clinical outcome.

Our experience also suggests that dose escalation from 800 mg to 1,200 mg daily in an attempt to increase posaconazole levels was largely ineffective. We found that only 29% (2/7) of our patients achieved serum trough levels >0.5 μg/ml when the dose was increased to 1,200 mg/day. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that no further increases in plasma drug concentrations were noted in healthy volunteers or neutropenic patients receiving 1,200 mg daily compared with 800 mg daily (5, 12). To our knowledge, however, this is the first report of increased serum drug levels in response to doses of 1,600 mg/day. The finding that higher levels were achieved with the 1,600-mg daily dosage was not suspected, given the current belief that absorption of posaconazole is saturated beyond 800 mg (5). Indeed, our findings suggest that repeated high doses of posaconazole may overcome the limits of saturable absorption or point to a new transport mechanism for this agent. Unfortunately, the 1,600-mg daily dosage was not well tolerated in our patients due to gastrointestinal distress and hepatotoxicity. Until further data are available, we do not advocate using higher-than-recommended doses in response to subtherapeutic posaconazole levels. Rather, we urge clinicians to correct modifiable patient factors that may improve oral absorption.

In conclusion, we have highlighted the challenges of posaconazole use in cardiothoracic transplant recipients. It is important for clinicians to recognize that experience in HSCT patients cannot necessarily be extrapolated to SOT or other populations. Clearly, further studies of posaconazole in diverse groups are needed to optimize the use of this antifungal agent.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lloyd Clarke for assistance with data extraction.

Potential conflicts of interest are as follows. M.H.N. has received research funding from Pfizer, Enzon Pharmaceuticals, and Merck. E.J.K. and F.P.S. have received research funding from Pfizer. C.J.C. has received research funding from Pfizer, Astellas, and Merck. R.K.S. has received research funding from Astellas and Merck.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andes, D., A. Pascual, and O. Marchetti. 2009. Antifungal therapeutic drug monitoring: established and emerging indications. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:24-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blondeau, K., et al. 2009. Nocturnal weakly acidic reflux promotes aspiration of bile acids in lung transplant recipients. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 28:141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calanas-Continente, A. J., et al. 2002. Prevalence of malnutrition among candidates for lung transplantation. Nutr. Hosp. 17:197-203. (In Spanish.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clancy, C. J., V. L. Yu, A. J. Morris, D. R. Snydman, and M. H. Nguyen. 2005. Fluconazole MIC and the fluconazole dose/MIC ratio correlate with therapeutic response among patients with candidemia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3171-3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courtney, R., S. Pai, M. Laughlin, J. Lim, and V. Batra. 2003. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of oral posaconazole administered in single and multiple doses in healthy adults. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2788-2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodds Ashley, E. S., et al. 2009. Pharmacokinetics of posaconazole administered orally or by nasogastric tube in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2960-2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang, S. H., P. M. Colangelo, and J. V. Gobburu. 2010. Exposure-response of posaconazole used for prophylaxis against invasive fungal infections: evaluating the need to adjust doses based on drug concentrations in plasma. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 88:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kohl, V., et al. 2010. Factors influencing pharmacokinetics of prophylactic posaconazole in patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:207-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishna, G., et al. 2008. Pharmacokinetics of oral posaconazole in neutropenic patients receiving chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. Pharmacotherapy 28:1223-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishna, G., M. Martinho, P. Chandrasekar, A. J. Ullmann, and H. Patino. 2007. Pharmacokinetics of oral posaconazole in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients with graft-versus-host disease. Pharmacotherapy 27:1627-1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishna, G., A. Moton, L. Ma, M. M. Medlock, and J. McLeod. 2009. Pharmacokinetics and absorption of posaconazole oral suspension under various gastric conditions in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:958-966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanser, S., S. J. McNabb, and J. M. Horan. 1994. A computerized surveillance system for disease outbreaks in Oklahoma. Am. J. Public Health 84:2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, Y., U. Theuretzbacher, C. J. Clancy, M. H. Nguyen, and H. Derendorf. 2010. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profile of posaconazole. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 49:379-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pappas, P. G., et al. 2010. Invasive fungal infections among organ transplant recipients: results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET). Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:1101-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segal, B. H., et al. 2008. Defining responses to therapy and study outcomes in clinical trials of invasive fungal disease: Mycoses Study Group and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus criteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47:674-683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vadnerkar, A., et al. 6 December 2010, posting date. Age-specific complications among lung transplant recipients 60 years of age and older. J. Heart Lung Transplant. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Walsh, T. J., et al. 2007. Treatment of invasive aspergillosis with posaconazole in patients who are refractory to or intolerant of conventional therapy: an externally controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:2-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winston, D. J., K. Bartoni, M. C. Territo, and G. J. Schiller. 8 May 2010, posting date. Efficacy, safety, and breakthrough infections associated with standard long-term posaconazole antifungal prophylaxis in allogeneic stem-cell transplant recipients. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed]