Abstract

Fluoroquinolones, which target gyrase and topoisomerase IV, are used for treating Streptococcus pneumoniae infections. Fluoroquinolone resistance in this bacterium can arise via point mutation or interspecific recombination with genetically related streptococci. Our previous study on the fitness cost of resistance mutations and recombinant topoisomerases identified GyrAE85K as a high-cost change. However, this cost was compensated for by the presence of a recombinant topoisomerase IV (parC and parE recombinant genes) in strain T14. In this study, we purified wild-type and mutant topoisomerases and compared their enzymatic activities. In strain T14, both gyrase carrying GyrAE85K and recombinant topoisomerase IV showed lower activities (from 2.0- to 3.7-fold) than the wild-type enzymes. These variations of in vitro activity corresponded to changes of in vivo supercoiling levels that were analyzed by two-dimensional electrophoresis of an internal plasmid. Strains carrying GyrAE85K and nonrecombinant topoisomerases had lower (11.1% to 14.3%) supercoiling density (σ) values than the wild type. Those carrying GyrAE85K and recombinant topoisomerases showed either partial or total supercoiling level restoration, with σ values being 7.9% (recombinant ParC) and 1.6% (recombinant ParC and recombinant ParE) lower than those for the wild type. These data suggested that changes acquired by interspecific recombination might be selected because they reduce the fitness cost associated with fluoroquinolone resistance mutations. An increase in the incidence of fluoroquinolone resistance, even in the absence of further antibiotic exposure, is envisaged.

In spite of the development of vaccines and chemotherapy, Streptococcus pneumoniae continues to be a main human pathogen, due in part to its high rate of resistance to antibiotics and in part to the low coverage and partial inefficiency of available vaccines. The World Health Organization estimates that about 1 million children aged <5 years die annually of pneumococcal pneumonia, meningitis, and/or sepsis worldwide (65). After the usage of the pneumococcal 7-valent conjugate vaccine in children, which includes most of the antibiotic-resistant serotypes, the incidence of invasive disease declined in both children and adults, reflecting herd immunity (34, 64). This was associated with a decline in penicillin resistance rates in many countries (17, 34, 52). However, emergence of serotypes not included in the vaccine, especially multiresistant serotype 19A, has been observed (9, 17, 44).

Pneumococcal resistance to β-lactams and macrolides has spread worldwide in the last 3 decades (27). Currently, new respiratory fluoroquinolones, which target DNA gyrase (gyrase) and DNA topoisomerase IV (topo IV), the essential type II DNA topoisomerases, are recommended as therapeutic alternatives for treatment of adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia (38). DNA topoisomerases catalyze the interconversions of different topological DNA forms and thus solve the topological problems associated with DNA replication, transcription, and recombination (7). DNA supercoiling is maintained in bacteria homeostatically by the opposing activities of topoisomerases that relax DNA and by gyrase, which introduces negative supercoils. In Escherichia coli, transcription of the DNA topoisomerase I gene increases when negative supercoiling increases (62), and that of the gyrase genes increases after DNA relaxation (41-43). Likewise, gyrase upregulation in response to relaxation has also been observed in Streptomyces and Mycobacterium (60, 63). We have recently described the transcriptional response to DNA relaxation that affects all S. pneumoniae topoisomerases, triggering the upregulation of gyrase and the downregulation of topoisomerases I and IV (19). We have shown that the pneumococcal genome is organized in topology-reacting gene clusters that share particular AT content and codon composition characteristics (19). S. pneumoniae is part of the commensal flora of the human nasopharynx. However, under specific circumstances, it migrates to other niches (ear, lung, bloodstream, cerebrospinal fluid), causing diverse pathologies. Since the level of bacterial DNA supercoiling is affected by diverse environmental conditions (13, 56, 61) and global genome transcription is dependent on the degree of supercoiling (19, 25, 29, 51), changes in DNA topology would be crucial for cell viability and for the infective capacity of S. pneumoniae on its diverse niches (with diverse environmental conditions) in the human host.

Gyrase (GyrA2GyrB2) introduces negative supercoils into DNA (23), and topo IV (ParC2ParE2) acts mainly in chromosome partitioning (31). Fluoroquinolones inhibit these enzymes by forming a ternary complex of drug, enzyme, and DNA. Cellular processes acting on this complex would yield to the formation of irreparable double-stranded DNA breaks that cause bacterial death (14). Genetic and biochemical studies have shown that ciprofloxacin (CIP) and levofloxacin target primarily topo IV and secondarily gyrase in S. pneumoniae (18, 28, 45, 48, 59). However, for moxifloxacin, gyrase is the primary target (26).

Fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates carry mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs), which are located in the N terminus of ParC or GyrA and in the C terminus of ParE. Although CIP is not an effective antipneumococcal drug, we used it to detect fluoroquinolone resistance and considered a CIP resistance breakpoint MIC of ≥4 μg/ml to improve detection of first-step mutant strains (8, 10, 11). Low-level-CIP-resistant strains (MICs, 4 to 8 μg/ml) had mutations altering the QRDRs of one of the two subunits of topo IV: S79, S80, or D83 of ParC (10, 28, 45) and D435 of ParE (50). High-level-CIP-resistant strains (MICs, ≥16 μg/ml) had additional GyrA changes (S81 or E85) (28, 45).

A study (in the years 2004 and 2005) including 15 European countries (54) showed a low level (<3%) of fluoroquinolone resistance in S. pneumoniae in all countries, with the exception of Poland (4.4%), Finland (6.6%), and Italy (7.2%). Higher rates have been detected in some Asian countries (21), as well as in Canada (1). In Canada, an increase in the rate of CIP resistance between 1998 (0.6%) and 2006 (7.3%) occurred in conjunction with increased consumption (1). In Spain, two epidemiological studies performed in 2002 (11) and 2006 (10) showed a stable low rate of CIP resistance (≤2.3%), maybe influenced by the stabilization of CIP consumption during this period. However, an increase in resistance in some European countries in which fluoroquinolone use has increased (data from European surveillance of antimicrobial consumption, http//www.esac.ua.ac.be) is not unexpected.

Resistance changes can be acquired either by spontaneous mutation or by intraspecific (58) or interspecific (5, 11, 20, 58) recombination with related streptococci of the mitis group (SGM). The fluoroquinolone-resistant pneumococcal recombinant isolates studied by our group have acquired portions of either parE (unpublished results), parC (11), or parE plus parC (5, 11, 20) from SMG. In the latter case, given the presence of the ant gene in the intergenic parE-parC region of SMG, recombinants acquired an extra gene in the recombination process and, consequently, had larger intergenic parE-parC regions (1.1 to 7.2 kb) than nonrecombinant pneumococci (0.4 kb).

The evolution of antibiotic resistance depends on the balance between antibiotic use and the fitness cost (typically observed as a reduced growth rate) imposed by resistance mutations (2). A direct relation between fluoroquinolone consumption and an increase in the rate of resistance in S. pneumoniae has been described (8, 36). In addition, fitness depends on the specific drug-mutation combination (15, 22, 33, 37), and compensatory mutations that ameliorate the fitness loss have been described (6). There are a few reports on the fitness cost of fluoroquinolone resistance mutations in S. pneumoniae (4, 24, 30, 55), and there is only one report of a study in which recombinant strains were considered (4). In our previous study, we analyzed a set of 24 CIP-resistant isogenic strains and categorized the mutations as conferring no, a low, or a high biological cost to the strains (4). The mutation causing the GyrAE85K change was identified as a high-cost mutation. However, the fitness cost imposed by this change was compensated for by the presence of a recombinant topo IV in strain T14. A single study, in which enzymatic activity determinations were not made, has related the fitness cost of quinolone resistance mutations in E. coli gyrase and supercoiling level, measured by monodimensional agarose gel electrophoresis (3). In this study, we combined high-resolution two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis with enzymatic assays to get insight into the compensation of the fitness cost imposed by GyrAE85K by the presence of a recombinant topo IV enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth, and transformation of bacteria.

The S. pneumoniae strains used were wild-type (wt) R6 and its isogenic derivatives Tr7, T1, T4, T9, and T14 (4). They were grown in a casein hydrolysate-based medium with 0.3% sucrose (AGCH) as the energy source and transformed as described previously (35). E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and transformed as described previously (57). The pQE1 vector/E. coli M15 host system (Qiagen) was used to overexpress S. pneumoniae GyrB, GyrA, ParC, and ParE proteins in E. coli.

Cloning of topoisomerase genes, protein overexpression, and purification.

Genes were amplified from chromosomal DNA of strains R6, T1, T9, or T14. Forward oligonucleotides were previously phosphorylated, and reverse primers contained SphI restriction sites at their 5′ ends (Table 1). Amplifications (50 μl) were performed with 2.5 U of Pfu DNA polymerase (Fermentas), 0.1 μg of template DNA, 1 μM (each) oligonucleotide primers, and 0.2 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates. PCRs included 1 cycle of 5 min of denaturation at 94°C, 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C and 1 min at 55 or 45°C, a 3-min polymerase extension step at 72°C, a final 5-min extension step at 72°C, and slow cooling at 4°C. Oligonucleotides were removed (QIAquick PCR purification kit; Qiagen), and the PCR products were cut with SphI, cloned into plasmid pQE1 digested with SphI-PvuII, and established in E. coli M15(pREP4). Transformants were selected on LB plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml; for pQE1 selection) and kanamycin (25 μg/ml; for pREP4 selection). The pQE1 vector/M15(pREP4) system permits the controlled hyperproduction of proteins with an N-terminal Met-Lys-(His)6-Gln fusion encoded by genes placed under the control of a phage T5 promoter and two lac operator sequences. Plasmid pREP4 constitutively expresses the LacI repressor. Expression of recombinant proteins cloned into pQE vectors is induced by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), which binds to LacI and inactivates it. This inactivation allows the host cell's RNA polymerase to transcribe the sequences downstream from the T5 promoter. The various E. coli M15(pREP4) strains harbored pQE1 recombinant plasmids carrying either the parC (from R6, T1, T9, and T14), parE (from R6 and T14), gyrA (from R6 and T14), or gyrB (from R6) gene. Strains were grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium, diluted 20-fold in 200 ml medium, and grown at 37°C (for GyrB or ParE overproduction) or at 30°C (for GyrA or ParC overproduction) until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was 0.6. At this moment, 1 mM IPTG was added and growth was continued for another 30 min. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation and suspended in 4 ml of 50 mM NaH2PO4-300 mM NaCl (column buffer) containing 10 mM imidazole, before they were flash frozen in dry ice. The suspension was thawed at 0°C and incubated for 30 min with lysozyme (1 mg/ml) and Triton X-100 (0.2%). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C), and the supernatant was mixed with 2 ml of 50% nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin slurry (Qiagen) by slow agitation on a rotary shaker at 4°C for 1 h. The mixture was packed in a column and washed with 8 ml of column buffer containing 20 mM imidazole. His-tagged proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 50 to 250 mM imidazole in column buffer. Protein fractions were examined by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and those containing proteins of the expected size were pooled and dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 50% glycerol.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this work

| Oligonucleotidea | Sequence (5′-3′)b |

|---|---|

| pLS1F | GTGCCGAGTGCCAAAATCAA |

| pLS1R | TTTCAAGTACCGATTCACTTAATG |

| pBR-1 | CGGTGAAAACCTCTGACACA |

| pBR-2 | CGCCACCTCTGACTTGAGC |

| gyrAF | ATGCAGGATAAAAATTTAGTG |

| gyrAR | gcgcgcatgcGCCAGTGACAGTAATATCAGAAATCCTGC |

| gyrBF | ATGACAGAAGAAATCAAAAATCTGC |

| gyrBR | gcgcgcatgcGACCAAGGGAACTACTTCTCCC |

| parCF | ATGTCTAACATTCAAAACATGTCCC |

| parCR | gcgcgcatgcCCTCCAATAAAAACCATC |

| parEF | GTGTCAAAAAAGGAAATC |

| parER | gcgcgcatgcCATAGTCATTCACATCCGACTC |

| T11parER | gcgcgcatgcCCGTGAACCAGACATGGCCACAGCCG |

F, forward; R, reverse.

The 5′ ends of some of the primers contained a sequence including a SphI restriction site, which is underlined. Bases not present in the R6 strain sequence are lowercase.

Topoisomerase catalytic assays.

Gyrase and topo IV were reconstituted by incubation of their corresponding subunits with an excess of GyrB or ParE subunits (1:3.8 ratio) for 1 h at 4°C. Gyrase-mediated supercoiling reactions (100 μl) were performed for 1 h at 37°C as described previously (18) using 0.4 μg of relaxed pBR322 DNA (Inspiralis, Norwich, United Kingdom) and reconstituted gyrase. The reaction was terminated by addition of 7.5 μl of 0.5 M EDTA (1-min incubation) and further addition of 1% SDS and 50 μg/ml proteinase K (15-min incubation at 37°C). Samples were ethanol precipitated, suspended in electrophoresis loading buffer, and analyzed in 1% agarose gels run at 2 V/cm for 12 h. Topo IV decatenation assays (12 μl) were performed as described previously (18) using 0.4 μg of concatenated kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) from Crithidia fasciculata (Inspiralis) and reconstituted topo IV. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h and terminated by addition of 6 μl of loading buffer and 12 μl of H2O. Samples were analyzed by electrophoresis in 0.7% agarose gels run at 3 V/cm for 1 h and then at 7 V/cm for 2 h. Relaxation assays (20 μl) were performed as described previously (49) using 50 ng of supercoiled pBR322 and a 12.5-fold larger amount of reconstituted topo IV than that used in the decatenation assay. Samples were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1.4% agarose gels run at 1.8 V/cm for 22 h. After electrophoresis, gels were subjected to Southern hybridization using a 506-bp pBR322 probe obtained by amplification of plasmid DNA with 5′-biotinylated pBR-1 and pBR-2 oligonucleotides (Table 1). Southern blotting and hybridization were performed following the Phototope-Star kit (New England BioLabs) instructions. Cleavage assays were carried out either in 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 6 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 200 mM potassium glutamate and 50 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) (for topo IV) or in 35 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 24 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, and 0.1 mg/ml BSA (for gyrase). Reconstituted topoisomerases were incubated with 0.4 μg of supercoiled pBR322 in 25-μl reaction mixtures in the presence of different concentrations of ciprofloxacin to account for 16× MIC for each strain (for topo IV) or for 100× MIC (for gyrase). After a 30-min incubation at 37°C, 1 μl of 10% SDS and 2 μl of 20 mg/ml proteinase K were added, and incubation was continued for 30 min at 45°C. Loading buffer was added to the samples, which were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels, which were run at 2 V/cm for 12 h.

Two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis.

Isolation of plasmid DNA from S. pneumoniae cultures grown on AGCH containing 1 μg/ml of tetracycline (for selection of pLS1) was performed using a neutral method to avoid plasmid denaturation. Exponentially growing cells were harvested and lysed by treatment with lysozyme and a detergent solution of 1% Brij 58 and 0.4% sodium deoxycholate (40). Plasmid molecules were analyzed in neutral/neutral two-dimensional agarose gels. The first dimension was run in a 0.4% (wt/vol) agarose (Seakem; FMC Bioproducts) gel in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer containing 1 μg/ml of chloroquine (Sigma) at 1.5 V/cm at room temperature for 19 h. The second dimension was run in a 1% agarose gel in TBE buffer containing 2 μg/ml of chloroquine at 7.5 V/cm for 7 to 9 h at 4°C. Chloroquine was added to the TBE buffer in both the agarose and the running buffer. After electrophoresis, gels were subjected to Southern hybridization using a 240-bp PCR fragment obtained from pLS1 DNA with 5′-biotinylated pLS1F and pLS1R (Table 1) as probes on gels transferred to nylon membranes (Inmobylon NY+; Millipore). Chemiluminescent detection of DNA was performed with the Phototope-Star kit (New England BioLabs). Images were captured in a VersaDoc MP400 system and analyzed with the Quantity One program (Bio-Rad). DNA linking number (Lk) was analyzed by quantifying the amount of every given topoisomer. DNA supercoiling density (σ) was calculated by ΔLk/Lk0, where ΔLk is the linking number difference. ΔLk values were determined with the equation Lk − Lk0, in which Lk0 (the linking number of the molecule when relaxed) = N/10.5, where N is the DNA size (in bp; 4,408 bp for pLS1) and 10.5 is the number of bp per one complete turn in B-DNA, the most probable helical repeat of DNA under the conditions used.

RESULTS

Mutant DNA topoisomerases are less active than wild-type enzymes.

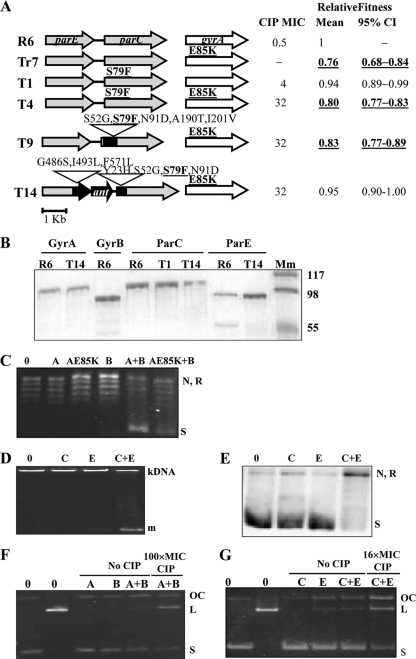

Five strains (Fig. 1 A) which carry various fluoroquinolone resistance mutations and parE-parC structures were selected for this study from among a series of isogenic R6-derived strains previously constructed (4). While strain T1, which was used as a control, carried ParCS79F as a single change, the remaining four strains carried GyrAE85K: one as a single change (Tr7) and three (T4, T9, and T14) in combination with ParCS79F. Of the last three strains, while T4 carried a nonrecombinant parC gene, T9 carried a recombinant parC and T14 carried both parE and parC recombinant genes and, accordingly, the ant gene in its intergenic region. Consequently, T9 and T14 carried recombinant topoisomerase subunits that have, in addition to changes involved in resistance, other changes (Fig. 1A) not involved in resistance (4). Changes present in recombinant ParC (recParC) of strain T9 were S52G, N91D, A190T, and I201V. Strain T14 had the S52G and N91D changes and carried, in addition, Y23H. The recombinant ParE (recParE) subunit of strain T14 carried the G486S, I493L, and F571L changes, which are not involved in resistance (Fig. 1A). The fitness cost of these strains has previously been determined in competition experiments with the R6 strain (4). In our previous study, mixed cultures of R6 and each isogenic resistant strain were incubated in antibiotic-free medium for 6 h (ca. 10 to 12 generations), diluted 1,000-fold, and regrown for an additional 6-h period. The number of viable cells was determined at 0 h, at the end of the first 6-h cycle, and after the second 6-h cycle. Strains were classified as high cost when they showed a relative mean fitness value lower than 1 both in one-cycle (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.79 to 0.99) and in two-cycle (95% CI = 0.63 to 0.89) competitive growth experiments. Low-cost strains showed a relative mean fitness value lower than 1 only in the two-cycle (95% CI = 0.81 to 0.99) experiments, while for the no-cost strains, the 95% CI of the mean relative fitness value includes the value of 1. From this classification, T1 was considered to be a low-fitness-cost strain, and all strains carrying GyrAE85K, except T14, which showed no cost, were classified as high-fitness-cost strains.

FIG. 1.

Characteristics of the strains used and of their gyrase and topo IV enzymes. (A) Amino acids that change in strains Tr7, T1, T4, T9, and T14 with respect to the strain R6 sequence are indicated, and those involved in fluoroquinolone resistance are showed in boldface and underlined. For each strain are shown their CIP MIC, mean relative fitness, and 95% CI calculated in competition experiments with R6 (4). Fitness cost categorized as high is shown in boldface and underlined. (B) Purified topoisomerase subunits revealed by staining with Coomassie blue. His-tagged proteins were overexpressed in E. coli, purified by nickel resin chromatography, and examined on an SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel. Lane Mm, molecular mass marker (kDa). Approximately 0.5 μg of each protein was loaded per well. (C) Supercoiling activity of gyrase subunits. Reaction mixtures contained no enzyme (lane 0), 142.5 fmol of GyrA (lane A) or GyrAE85K (lane AE85K), 541.5 fmol of GyrB (lane B), or reconstituted wild-type (lane A+B) and mutant (lane E85K+B) gyrase. N, nicked pBR322; R, relaxed pBR322; S, negatively supercoiled pBR322. (D) Decatenation activity of topo IV. Standard reaction mixtures contained either no enzyme (lane 0), 16 fmol of ParC (lane C), 61 fmol of ParE (lane E), or reconstituted topo IV (lane C+E). m, monomers. (E) Relaxation activity of topo IV. Standard reaction mixtures contained either no enzyme (lane 0), 2.5 pmol of ParC (lane C), 9.3 pmol of ParE (lane E), or reconstituted topo IV (lane C+E). (F) Stimulation of gyrase-mediated cleavage activity by CIP. Reaction mixtures contained either no enzyme (lanes 0), 1.1 pmol of GyrA (lane A), 5.9 pmol of GyrB (lane B), or reconstituted gyrase (lanes A+B). (G) Stimulation of topo IV-mediated cleavage activity by CIP. Reaction mixtures contained either no enzyme (lanes 0), 2.3 pmol of ParC (lane C), 8.7 pmol of ParE (lane E), or reconstituted topo IV (lanes C+E). (F and G) The different forms of plasmid pBR322 are indicated: OC, open circle; L, linear; S, negatively supercoiled.

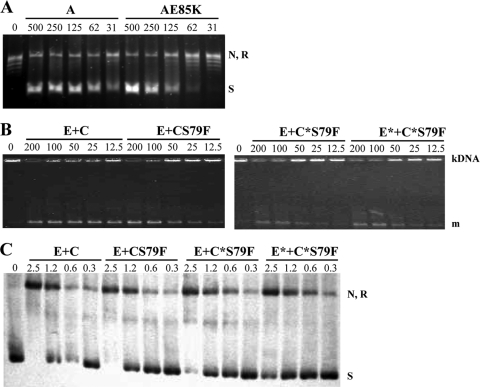

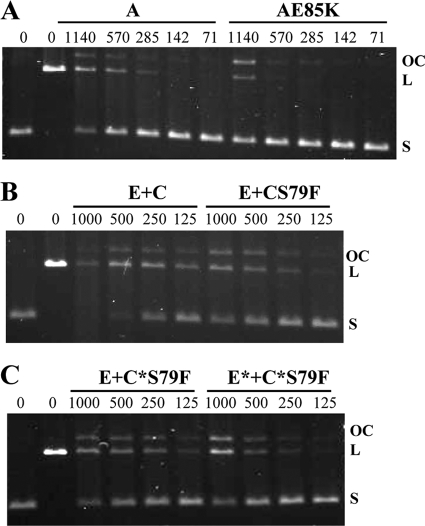

A series of His-tagged topoisomerase subunits were overexpressed and purified (Fig. 1B) in order to perform enzymatic assays. All wt subunits were obtained from strain R6, GyrAE85K was obtained from T14, ParC subunits were obtained from T1 and T14, and ParE was obtained from T14. Most proteins were obtained in soluble form with >90% homogeneity. However, additional bands of lower molecular weight were observed in GyrB and ParE of R6 (Fig. 1B). As shown below, these additional proteins did not interfere with the topoisomerase enzymatic assays used. The main gyrase activity, the ability to supercoil relaxed pBR322 in the presence of ATP, was assayed. No supercoiling activity was observed when either the GyrA (Fig. 1C, lanes A and AE85K) or the wt GyrB (Fig. 1C, lane B) subunits alone were assayed. Supercoiling activities were observed only when both subunits were combined (Fig. 1C, lanes A+B and AE85K+B). To achieve 50% supercoiling activity, 125 fmol and 250 fmol of the wt GyrA and GyrAE85K subunits, respectively, were required (Fig. 2 A), showing that the mutant subunit is 2-fold less active than the wild-type GyrA subunit (Table 2). Two activities were assayed for topo IV: decatenation and relaxation. Decatenation, which was assayed using kDNA as a substrate, was observed when the ParC and ParE subunits were combined (Fig. 1D, lanes C+E), while no activity was observed with either the ParC or the ParE subunit alone (Fig. 1D, lanes C and E). The decatenation activities of topo IV enzymes reconstituted with wt ParC (from R6) or ParC mutant subunits (ParCS79F from T1 and recParC S79F from T14) were compared. The ParE subunits assayed were wt ParE (from R6) and recParE from T14. As shown in Fig. 2, 50% decatenation activity was achieved with 50 fmol (wt ParC plus wt ParE), 100 fmol (ParCS79F plus wt ParE), 163 fmol (recParC S79F plus wt ParE), and 127 fmol (recParC S79F plus recParE) (Fig. 2B and C). These results showed that ParCS79F had 2-fold lower activity than wt ParC and that topo IV reconstituted with recParC or recParE plus recParC showed decatenation activities 3.3- and 2.5-fold lower, respectively, than the activity of wt topo IV (Table 2). Relaxation activity for topo IV was about 100-fold lower than that of decatenation, as has been previously described (49); for this reason, 50 ng instead 400 ng of supercoiled pBR322 was used as a substrate and the reaction products were detected after Southern blot hybridization as described in Materials and Methods. Relaxation was observed when the ParC and ParE subunits were combined (Fig. 1E, lane C+E), while no activity was observed with either the ParC or ParE subunit alone (Fig. 1E, lanes C and E). The relaxation activities of topo IV enzymes reconstituted as described above were compared. As shown in Fig. 2, 50% relaxation activity was achieved with 0.8 pmol (wt ParC plus wt ParE), 1.2 pmol (ParCS79F plus wt ParE), 1.2 pmol (recParCS79F plus wt ParE), and 1.6 pmol (recParC S79F plus recParE) (Fig. 2C). These results showed that ParCS79F and recParC had activities 1.5-fold lower than the activity of wt ParC and that topo IV reconstituted with recParE plus recParC showed relaxation activity 2.0-fold lower than that of wt topo IV (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

The supercoiling decatenation and relaxation activities of mutant topoisomerases are lower than those of the wild-type enzyme. (A) Gyrase supercoiling. Subunit wt GyrA or GyrAE85K (lane AE85K) was reconstituted with wt GyrB in a 1:3.8 proportion and used to supercoil relaxed plasmid pBR322 (0.4 μg) with various amounts of reconstituted gyrase (31 to 500 fmol GyrA). Lane 0, relaxed pBR322 substrate. (B) Decatenation activity of topo IV (lanes E+C) and its ParCS79F mutant (lanes E+CS79F) reconstituted with wt ParE, recParC (lanes E+C*S79F), or recParE plus recParC (lanes E*+C*S79F) in a 3.8:1 proportion (12.5 to 200 fmol ParC). Enzymes were incubated with kDNA (0.4 μg). m, monomers. (C) Relaxation activity of topo IV and its ParCS79F mutant reconstituted with wt ParE, recParC, or recParE plus recParC in a 3.8:1 proportion (0.3 to 2.5 pmol ParC). Enzymes were incubated with 50 ng of supercoiled plasmid pBR322. N, nicked pBR322; R, relaxed pBR322; S, negatively supercoiled pBR322.

TABLE 2.

Enzymatic activities of type II DNA topoisomerases

| Strain source of subunit for purification |

Enzyme sp acta |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gyrase |

Topo IV |

|||||||

| ParC | ParE | GyrA | GyrB | Supercoilingb | Cleavagec | Decatenationd | Relaxatione | Cleavagef |

| - | - | R6 | R6 | 8.6 | 3.7 | - | - | - |

| - | - | T14 | R6 | 4.3 (2.0) | 1.0 (3.7) | - | - | - |

| R6 | R6 | - | - | - | - | 21.2 | 1.4 | 3.8 |

| T1 | R6 | - | - | - | - | 10.6 (2.0) | 0.9 (1.5) | 1.2 (3.2) |

| T14 | R6 | - | - | - | - | 6.5 (3.3) | 0.9 (1.5) | 1.4 (2.7) |

| T14 | T14 | - | - | - | - | 8.3 (2.5) | 0.7 (2.0) | 1.1 (3.4) |

Activities are in units/mg × 104, and numbers in parentheses are the fold decrease in activity with respect to that of the R6 enzyme.

One unit defined as the amount of enzyme required to convert 50% of 0.4 μg of relaxed pBR322 to the supercoiled form in 1 h at 37°C.

One unit defined as the amount of enzyme required to linearize 20% of 0.4 μg of CCC pBR322 in 30 min at 37°C.

One unit defined as the amount of enzyme required to decatenate 50% of 0.4 μg of kDNA in 1 h at 37°C.

One unit defined as the amount of enzyme required to convert 50% of 50 ng of CCC pBR322 to the open circle form in 1 h at 37°C.

One unit defined as the amount of enzyme required to linearize 50% of 0.4 μg of CCC pBR322 in 30 min at 37°C.

Since it has been suggested that fluoroquinolone action is better assayed by stimulation of topoisomerase-mediated cleavage, this assay was performed with both gyrase and topo IV in the presence of an excess of CIP (100× MIC and 16× MIC, respectively). In these assays, the enzyme is blocked in a reaction intermediary and renders linear DNA from covalently closed circular (CCC) pBR322 after treatment with proteinase K and SDS, as described in Materials and Methods. When the activities of the GyrA and GyrB subunits were analyzed, linearization was observed only when the GyrA and GyrB subunits were combined (Fig. 1F, lanes A+B), while no activity was observed with either subunit alone. When this cleavage assay was performed using wt GyrA and GyrAE85K subunits, 20% activity was achieved with 289 fmol (wt GyrA plus GyrB) and 1,035 fmol (GyrAE85K plus GyrB), showing that GyrAE85K had 3.7-fold lower activity than the wt enzyme (Fig. 3 A). When the activities of the ParC and ParE subunits of topo IV were analyzed (Fig. 1G), some linearization was observed when only the E subunit was used; however, this residual activity, which is probably due to the contaminating band observed in the purification (Fig. 1B), did not interfere with the assay. When ParC and ParE subunits were combined, a 3-fold greater activity was observed when the assay was performed in the presence of ciprofloxacin than in its absence (Fig. 1G). When this cleavage assay was used to test topo IV enzymes, 50% activity was achieved with 282 fmol (ParC plus wt ParE), 848 fmol (ParCS79F plus wt ParE), 740 fmol (recParC S79F plus wt ParE), and 963 fmol (recParCS79F plus recParE) (Fig. 3B and C). These results showed that topo IV carrying ParCS79F, recParC, and recParC plus recParE had 3.2-, 2.7-, and 3.4-fold lower cleavage activity than the wt enzyme, respectively (Table 2).

FIG. 3.

Mutant topoisomerases showed lower ciprofloxacin-promoted DNA cleavage activities than wild-type enzyme. (A) CIP-promoted DNA cleavage of gyrase. Plasmid pBR322 DNA (0.4 μg) was incubated with different amounts of reconstituted gyrase (lanes A) and its AE85K mutant (lanes AE85K), using 71 to 1,140 fmol GyrA. (B) CIP-promoted DNA cleavage with different amounts of reconstituted topo IV (lanes E+C) and its ParCS79F mutant (lanes E+CS79F), using 125 to 1,000 fmol ParC. (C) CIP-promoted DNA cleavage by topo IV with recParC (lanes E+C*S79F) or recParE plus recParC (lanes E*+C*S79F).

DNA topoisomer distribution varied in isogenic strains carrying the GyrAE85K change.

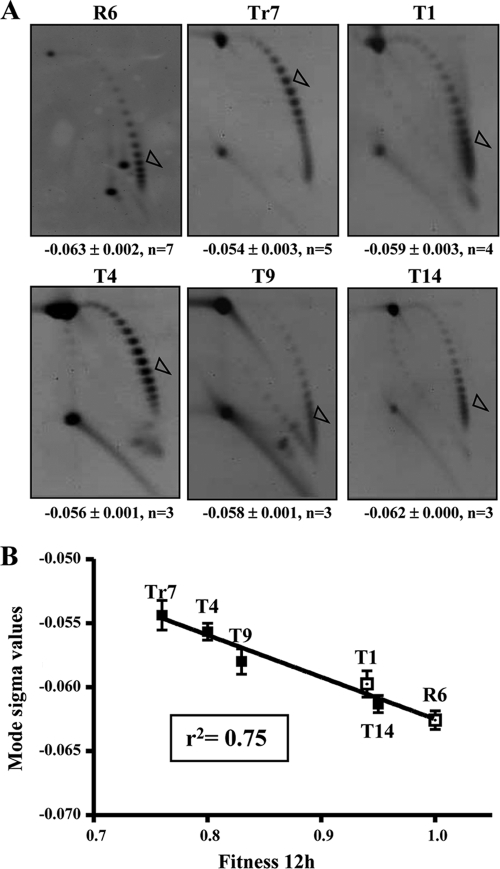

To estimate the supercoiling level in vivo, we analyzed the influence of the parC and gyrA mutations in the supercoiling level of plasmid pLS1, which is able to replicate in S. pneumoniae. This plasmid was introduced into strains R6, Tr7, T1, T4, T9, and T14, and their topoisomer distribution was analyzed by using two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4 A). The use of plasmid pLS1 is appropriate to study gyrase activity, given that it replicates by a rolling circle mechanism (12) and all its genes are transcribed in the same direction, avoiding problems of transcription interference during replication (47). Topoisomers were distributed in the autoradiograms in a bubble-shaped arc, with negatively supercoiled molecules being located to the right and positively supercoiled ones being located to the left (Fig. 4A). To calculate the σ values, it was considered that the induced ΔLk of monomers by 2 μg/ml chloroquine in pLS1 is −14 (19). No significant difference (6.3%) in σ values was observed between the wt strain R6 (−0.063) and T1 carrying the ParCS79F change (−0.059). However, σ values for strains carrying GyrAE85K, such as Tr7, which carries this single change (−0.054), and T4, which also carries ParCS79F (−0.056), were 14.3 and 11.1% lower, respectively, than the value for R6. These results suggest that the GyrAE85K change causes a supercoiling level deficiency. However, two recombinant strains (T9 and T14) that also carry GyrAE85K showed σ values that differed from those of the nonrecombinant (Tr7 and T4) strains. While T9 (recParC) had a σ value (−0.058) 7.9% lower than that of R6, T14 (recParC plus recParE) had a σ value (−0.062) equivalent (1.6% lower) to that of R6. Supercoiling densities and mean relative fitness after 12 h of competitive growth showed a good correlation (r2 = 0.75, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Supercoiling levels correlate with bacterial fitness. (A) Distribution of pLS1 topoisomers of the indicated isogenic strains after two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis run in the presence of 1 and 2 μg/ml chloroquine in the first and second dimensions, respectively. An empty arrowhead indicates the most abundant topoisomer. σ values are indicated below the image of one characteristic gel of each strain as the average ± standard deviation, n (number of determinations). (B) Correlation between supercoiling density and fitness at 12 h of growth in competition with R6. A black square indicates those strains carrying the GyrAE85K change.

DISCUSSION

Under laboratory conditions, the frequencies of CIP resistance acquisition via either interspecific recombination or mutation are about 10−3 (27, 30) and 10−9 (54), respectively. However, the prevalence of CIP-resistant S. pneumoniae clinical isolates that have acquired resistance by interchange with SMG is unexpectedly low, with such isolates accounting for 3 to 10% of the resistant isolates (5, 12, 63). Even when factors such as DNA availability and the competence state of the recipient cells in the natural environment could affect horizontal transfer, it has been estimated that the ratio of recombination/mutation in natural S. pneumoniae populations is 10:1 (17).

The fitness cost imposed by the DNA interchange could explain the low frequency of fluoroquinolone-resistant recombinant S. pneumoniae clinical isolates. Strain T14 had a parE-ant-parC structure and carries recParE plus recParC subunits. Two factors could theoretically affect the fitness of this recombinant; one is a putative discoordination of the parE-ant-parC operon transcription, and the other is the existence of recombinant topo IV subunits. With respect to the first factor, we have previously shown that transcription of the operon from a promoter located upstream of parE was not affected either in T14 or in other clinical isolates with small (<2-kb) intergenic regions (4). With respect to the second factor, it would be expected that a recombinant gyrase or topo IV enzyme, which has a tetrameric structure, would be a less efficient enzyme than a nonrecombinant one and would cause a fitness cost to the strain that carried it. However, strain T14 shows a compensation for the fitness cost imposed by the GyrAE85K change (4), maintaining its chromosome supercoiling level due to the conjunction of suboptimal activities of its recombinant topo IV and mutant gyrase enzymes. Since the strains analyzed in this study were isogenic, no alteration in topoisomerase I activity is expected. We showed that the reduced gyrase activity on supercoiling produces a decrease in bacterial fitness, which is compensated for by a reduced relaxing activity of topo IV. The two effects balance to give a nearly wild-type level of supercoiling and, thus, of bacterial fitness.

Gyrase enzymatic assays showed that the GyrAE85K enzyme has lower activity (Fig. 2 and 3; Table 2) than the wt enzyme. As a consequence, the supercoiling level detected in pLS1 of strains carrying this change is affected. Although we have not measured the supercoiling level of the bacterial chromosome, the values obtained on small plasmids provide a good estimate of chromosomal supercoiling (53). Supercoiling density values for plasmid pLS1 in strains Tr7 and T4, which carry GyrAE85K, were 14.3 and 11.1% lower, respectively, than the value for the wt strain (Fig. 4). However, the recombinant strain showed a recovery. Full recovery of the supercoiling level (σ value, −0.062, equivalent to that of R6) was observed in strain T14 (recParC plus recParE), which is in accordance with the lower activities of its topo IV enzyme. Then, the lower enzymatic activities of gyrase and topo IV of strain T14 allowed an appropriate supercoiling level in vivo. Likewise, partial restoration of the supercoiling level (σ value, 7.9% lower than that of R6) was observed in T9 (recParC). Although we do not have purified topo IV of strain T9, it can be assumed that its activity would be equivalent to that of recParC S79F from T14 and wt ParE from R6. Then, the partial restoration of σ values could be due to a lower level of activity of its topo IV enzyme.

The lower levels of activity of the recombinant topo IV enzymes from T9 and T14 could be attributed in part to the presence of the ParCS79F change involved in resistance and in part to the rest of the amino acid changes not involved in resistance. Of their 3.3-fold (T9) and 2.5-fold (T14) lower levels of activity detected in decatenation assays, only part (about 2-fold) could be attributed to the ParCS79F change of strain T1. Likewise, of the 2.0-fold lower level of activity detected in relaxation assays of T14, only part (about 1.5-fold) could be attributed to the ParCS79F change. However, this correspondence was not total when the cleavage complex formation activity was considered: activity decreases for ParCS79F (3.2-fold), recParC S79F (2.7-fold), and recParC S79F plus recParE (3.4-fold) with respect to the activity of the wt ParC do not perfectly fit with the estimated in vivo supercoiling level. These differences may be due to the in vitro activity conditions that do not necessarily reflect the in vivo conditions. Nevertheless, a good correlation was observed between σ values and mean relative fitness (Fig. 4B). These results show that the in vivo determinations are more accurate and sensitive than the enzymatic assays in vitro and suggest that the fitness cost is related to the level of supercoiling of the plasmid and, presumably, of the chromosome.

In conclusion, the presence of suboptimal topoisomerases, both gyrase that introduces negative supercoils and topo IV that relaxes DNA, allows the restoration of wild-type supercoiling levels and bacterial fitness. A similar phenomenon was noticed in E. coli fluoroquinolone-resistant strains, where the addition of a parC resistance mutation to an already-low-fitness gyrase mutant caused a further reduction in drug susceptibility and an increase in relative fitness (39).

The variations in the σ values of the various strains used in our study were in the 1.6% (T14) to 14.3% (Tr7) range. These values are considerably lower than the 23% variation that triggers a global transcriptional response in S. pneumoniae, which includes upregulation of gyrase and downregulation of relaxing topoisomerases and allows the recovery of the supercoiling levels (19). To test if an inherent transcriptional response occurred in the strains used in our study, real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) experiments were performed to detect changes in the expression of topoisomerase genes. No significant variations (data not shown) were detected, suggesting that either σ variations of >14.3% are necessary to trigger the supercoiling homeostatic response or that real-time RT-PCR is not sensitive enough to detect the predicted low levels of variation in transcription of the topoisomerase genes.

It is well-known that the fitness cost of drug resistance can be reduced by selection of low-cost mutations (4, 30, 55) or by accumulation of secondary fitness-compensating mutations that do not reduce resistance (32, 46). During evolution, compensatory mutations that arise spontaneously are selected because they provide a competitive advantage. Our data show that mutations acquired by S. pneumoniae by interspecific recombination might be selected because they reduce the fitness costs of some fluoroquinolone resistance mutations. Given the 10:1 prevalence of transformation versus mutation in natural S. pneumoniae populations (16), an increase in the incidence of fluoroquinolone resistance, even in the absence of additional antibiotic exposure, is envisaged.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants BIO2008-02154 from Plan Nacional de I+D+I of the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and COMBACT-S-BIO-0260/2006 from the Comunidad de Madrid. Ciber Enfermedades Respiratorias is an initiative from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. A. G. de la Campa is an Investigador Científico from the CSIC.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam, H. J., D. J. Hoban, A. S. Gin, and G. G. Zhanel. 2009. Association between fluoroquinolone usage and a dramatic rise in ciprofloxacin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Canada, 1997-2006. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34:82-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, D. I., and D. Hughes. 2010. Antibiotic resistance and its cost: is it possible to reverse resistance? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:260-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagel, S., V. Hullen, B. Wiedemann, and P. Heisig. 1999. Impact of gyrA and parC mutations on quinolone resistance, doubling time, and supercoiling degree of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:868-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balsalobre, L., and A. G. de la Campa. 2008. Fitness of Streptococcus pneumoniae fluoroquinolone-resistant strains with topoisomerase IV recombinant genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:822-830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balsalobre, L., M. J. Ferrándiz, J. Linares, F. Tubau, and A. G. de la Campa. 2003. Viridans group streptococci are donors in horizontal transfer of topoisomerase IV genes to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2072-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorkholm, B., et al. 2001. Mutation frequency and biological cost of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:14607-14612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Champoux, J. J. 2001. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:369-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, D. K., A. McGeer, J. C. de Azavedo, and D. E. Low. 1999. Decreased susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to fluoroquinolones in Canada. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi, E. H., et al. 2008. Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19A in children, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:275-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Campa, A. G., et al. 2009. Changes in fluoroquinolone-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae after 7-valent conjugate vaccination, Spain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:905-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de la Campa, A. G., et al. 2004. Fluoroquinolone resistance in penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae clones, Spain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1751-1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Campa, A. G., G. H. del Solar, and M. Espinosa. 1990. Initiation of replication of plasmid pLS1. The initiator protein RepB acts on two distant DNA regions. J. Mol. Biol. 213:247-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorman, C. J. 1991. DNA supercoiling and environmental regulation of gene expression in pathogenic bacteria. Infect. Immun. 59:745-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drlica, K., M. Malik, R. J. Kerns, and X. Zhao. 2008. Quinolone-mediated bacterial death. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:385-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ender, M., N. McCallum, R. Adhikari, and B. Berger-Bachi. 2004. Fitness cost of SCCmec and methicillin resistance levels in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2295-2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feil, E. J., et al. 2001. Recombination within natural populations of pathogenic bacteria: short-term empirical estimates and long-term phylogenetic consequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:182-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenoll, A., et al. 2009. Temporal trends of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes and antimicrobial resistance patterns in Spain from 1979 to 2007. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1012-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernández-Moreira, E., D. Balas, I. González, and A. G. de la Campa. 2000. Fluoroquinolones inhibit preferentially Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA topoisomerase IV than DNA gyrase native proteins. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:259-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrándiz, M. J., A. J. Martín-Galiano, J. B. Schvartzman, and A. G. de la Campa. 2010. The genome of Streptococcus pneumoniae is organized in topology-reacting gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:3570-3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrándiz, M. J., A. Fenoll, J. Liñares, and A. G. de la Campa. 2000. Horizontal transfer of parC and gyrA in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:840-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuller, J. D., and D. E. Low. 2005. A review of Streptococcus pneumoniae infection treatment failures associated with fluoroquinolone resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:118-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gagneux, S., et al. 2006. The competitive cost of antibiotic resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 312:1944-1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gellert, M., K. Mizuuchi, M. H. O'Dea, and H. A. Nash. 1976. DNA gyrase: an enzyme that introduces superhelical turns into DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 73:3872-3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gillespie, S. H., L. L. Voelker, J. E. Ambler, C. Traini, and A. Dickens. 2003. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: evidence that gyrA mutations arise at a lower rate and that mutation in gyrA or parC predisposes to further mutation. Microb. Drug Resist. 9:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gmüender, H., et al. 2001. Gene expression changes triggered by exposure of Haemophilus influenzae to novobiocin or ciprofloxacin: combined transcription and translation analysis. Genome Res. 11:28-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Houssaye, S., L. Gutmann, and E. Varon. 2002. Topoisomerase mutations associated with in vitro selection of resistance to moxifloxacin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2712-2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobs, M. R., D. Felmingham, P. C. Appelbaum, R. N. Grüneberg, and the Alexander Project Group. 2003. The Alexander project 1998-2000: susceptibility of pathogens isolated from community-acquired respiratory tract infection to commonly used antimicrobial agents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:229-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janoir, C., V. Zeller, M.-D. Kitzis, N. J. Moreau, and L. Gutmann. 1996. High-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae requires mutations in parC and gyrA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2760-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeong, K. S., Y. Xie, H. Hiasa, and A. B. Khodursky. 2006. Analysis of pleiotropic transcriptional profiles: a case study of DNA gyrase inhibition. PLoS Genet. 2:e152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson, C. N., D. E. Briles, W. H. Benjamin, S. K. Hollingshead, and K. B. Waites. 2005. Relative fitness of fluoroquinolone-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:814-820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato, J., et al. 1990. New topoisomerase essential for chromosome segregation in E. coli. Cell 63:393-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Komp Lindgren, P., L. L. Marcusson, D. Sandvang, N. Frimodt-Moller, and D. Hughes. 2005. Biological cost of single and multiple norfloxacin resistance mutations in Escherichia coli implicated in urinary tract infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2343-2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kusuma, C., A. Jadanova, T. Chanturiya, and J. F. Kokai-Kun. 2007. Lysostaphin-resistant variants of Staphylococcus aureus demonstrate reduced fitness in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:475-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kyaw, M. H., et al. 2006. Effect of introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. N. Engl. J. Med. 354:1455-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lacks, S. A., P. López, B. Greenberg, and M. Espinosa. 1986. Identification and analysis of genes for tetracycline resistance and replication functions in the broad-host-range plasmid pLS1. J. Mol. Biol. 192:753-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liñares, J., A. G. de la Campa, and R. Pallarés. 1999. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:1546-1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo, N., et al. 2005. Enhanced in vivo fitness of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:541-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandell, L. A., et al. 2007. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44(Suppl. 2):S27-S72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcusson, L. L., N. Frimodt-Moller, and D. Hughes. 2009. Interplay in the selection of fluoroquinolone resistance and bacterial fitness. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martín-Parras, L., et al. 1998. Topological complexity of different populations of pBR322 as visualized by two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:3424-3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menzel, R., and M. Gellert. 1987. Fusions of the Escherichia coli gyrA and gyrB control regions to the galactokinase gene are inducible by coumermycin treatment. J. Bacteriol. 169:1272-1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Menzel, R., and M. Gellert. 1987. Modulation of transcription by DNA supercoiling: a deletion analysis of the Escherichia coli gyrA and gyrB promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84:4185-4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menzel, R., and M. Gellert. 1983. Regulation of the genes for E. coli DNA gyrase: homeostatic control of DNA supercoiling. Cell 34:105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore, M. R., et al. 2008. Population snapshot of emergent Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19A in the United States, 2005. J. Infect. Dis. 197:1016-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muñoz, R., and A. G. de la Campa. 1996. ParC subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a primary target of fluoroquinolones and cooperates with DNA gyrase A subunit in forming resistance phenotype. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2252-2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagaev, I., J. Bjorkman, D. I. Andersson, and D. Hughes. 2001. Biological cost and compensatory evolution in fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 40:433-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olavarrieta, L., P. Hernández, D. B. Krimer, and J. B. Schvartzman. 2002. DNA knotting caused by head-on collision of transcription and replication. J. Mol. Biol. 322:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan, X.-S., J. Ambler, S. Mehtar, and L. M. Fisher. 1996. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2321-2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pan, X. S., and L. M. Fisher. 1999. Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV: overexpression, purification, and differential inhibition by fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1129-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perichon, B., J. Tankovic, and P. Courvalin. 1997. Characterization of a mutation in the parE gene that confers fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:166-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peter, B. J., et al. 2004. Genomic transcriptional response to loss of chromosomal supercoiling in Escherichia coli. Genome Biol. 5:R87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pilishvili, T., et al. 2010. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 201:32-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pruss, G., S. Manes, and K. Drlica. 1982. Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I mutants: increased supercoiling is corrected by mutations near gyrase genes. Cell 31:35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riedel, S., et al. 2007. Antimicrobial use in Europe and antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 26:485-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rozen, D. E., L. McGee, B. R. Levin, and K. P. Klugman. 2007. Fitness costs of fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:412-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rui, S., and Y. C. Tse-Dhin. 2003. Topoisomerase function during bacterial responses to environmental challenge. Front. Biosci. 8:d256-d263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 58.Stanhope, M. J., et al. 2005. Molecular evolution perspectives on intraspecific lateral DNA transfer of topoisomerase and gyrase loci in Streptococcus pneumoniae, with implications for fluoroquinolone resistance development and spread. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4315-4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tankovic, J., B. Perichon, J. Duval, and P. Courvalin. 1996. Contribution of mutations in gyrA and parC genes to fluoroquinolone resistance of mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae obtained in vivo and in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2505-2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thiara, A. S., and E. Cundliffe. 1993. Expression and analysis of two gyrB genes from the novobiocin producer, Streptomyces sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol. 8:495-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Travers, A., and G. Muskhelishvili. 2005. DNA supercoiling—a global transcriptional regulator for enterobacterial growth? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:157-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tse-Dinh, Y. C. 1985. Regulation of the Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I gene by DNA supercoiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 13:4751-4763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Unniraman, S., M. Chatterji, and V. Nagaraja. 2002. DNA gyrase genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a single operon driven by multiple promoters. J. Bacteriol. 184:5449-5456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whitney, C. G., et al. 2003. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1737-1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.World and Health Organization. 2007. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for childhood immunization—WHO position paper. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 82:93-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]