Abstract

PER-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Gram-negative bacilli are resistant to oxyimino-cephalosporins. However, the blaPER-1 gene has never been reported in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Here, we studied interspecies dissemination of the blaPER-1 gene by horizontal transfer of Tn1213 among Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae. In a K. pneumoniae clinical isolate, the blaPER-1 gene was located on a 150-kbp incompatibility group A/C plasmid.

The bla gene encoding PER-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL), which can hydrolyze penicillins, oxyimino-cephalosporins, and aztreonam but not oxacillins, cephamycins, and carbapenems, was first detected on a plasmid of Pseudomonas aeruginosa RNL-1 from France in 1991 (9). The widespread dissemination of the gene in Acinetobacter spp. (46%) and P. aeruginosa (11%) in Turkey was reported in 1997, and further dissemination of the gene into European countries, such as Italy, Belgium, and Russia, has been noted (5, 7, 8, 10, 19). In 2003, a high prevalence of the blaPER-1 gene in Acinetobacter spp. (55%) isolated from patients hospitalized in an intensive care unit (ICU) in Korea was reported, and further dissemination of the gene into Asian countries, such as China, Japan, and India, has also been detected (6, 20-22). The blaPER-1 gene has been detected mainly in glucose-nonfermenting Gram-negative bacilli, such as P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter spp., and Alcaligenes faecalis; however, it has also recently been found in Enterobacteriaceae, such as Providencia spp., Proteus spp., Salmonella spp., and Aeromonas media (2, 9, 11-13, 18, 19).

A 68-year-old female who presented with dyspnea and facial paralysis after a bamboo stick injury on the left leg was admitted to the ICU of a tertiary-care hospital in Gwangju, Republic of Korea, on 16 May 2006. She showed symptoms of pneumonia, and Acinetobacter baumannii and Staphylococcus aureus were repeatedly recovered from sputum specimens. Ceftazidime and vancomycin were administered for the treatment of pneumonia; however, she expired on 16 June due to the occurrence of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Klebsiella pneumoniae CS1711 isolate was recovered from the blood specimen obtained 1 day before she died.

Strain CS1711 exhibited resistance to ampicillin, piperacillin, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, cefepime, gentamicin, amikacin, and tetracycline and was susceptible to cefoxitin and imipenem by a disk diffusion assay (5). Synergy was observed between the amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (20 and 10 μg) disk and the ceftazidime (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), and aztreonam (30 μg) disks (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) in double-disk synergy tests, indicating the production of ESBL (17). Agar dilution MIC testing on Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) with an inoculum of 104 CFU per spot confirmed MICs of ceftazidime (MIC, 16 μg/ml), cefotaxime (MIC, 64 μg/ml), cefepime (MIC, 64 μg/ml), aztreonam (MIC, 16 μg/ml), cefoxitin (MIC, 4 μg/ml), amikacin (MIC, >256 μg/ml), and ciprofloxacin (MIC, 1 μg/ml) for strain CS1711 (17). Clavulanic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml lowered the MICs of ceftazidime, cefotaxime, and cefepime to 1 μg/ml, 0.12 μg/ml, and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

MICs of K. pneumoniae wild strain (CS1711), its transconjugant, and the recipient E. coli J53

| Antimicrobial agenta | MIC (μg/ml) of strains |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild strain, K. pneumoniae CS1711 | Transconjugant, E. coli trcCS1711 | Recipient, E. coli J53 | |

| Ceftazidime | 16 | 4 | 0.25 |

| Ceftazidime-clavulanic acid | 1 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Cefotaxime | 64 | 32 | 0.06 |

| Cefotaxime-clavulanic acid | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Cefepime | 64 | 8 | 0.06 |

| Cefepime-clavulanic acid | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Aztreonam | 16 | 8 | 0.25 |

| Cefoxitin | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Amikacin | >256 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 | 0.25 | 0.015 |

Clavulanic acid was added at a fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml.

The strain transferred an ∼150-kbp plasmid (pCS1711) to the Escherichia coli J53 azideR recipient in mating experiments in which transconjugants were selected on MacConkey agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) plates supplemented with cefotaxime (2 μg/ml) and sodium azide (100 μg/ml) (3). MICs of ceftazidime, cefotaxime, cefepime, amikacin, and ciprofloxacin for the transconjugant (trcCS1711) were 4 μg/ml, 32 μg/ml, 8 μg/ml, 0.25 μg/ml, and 0.025 μg/ml, respectively (Table 1).

PCR and sequencing experiments for the detection of genes encoding TEM-, SHV-, CTX-M-, GES-, VEB-, and PER-type ESBLs were performed as described previously (1) (Table 2). Strain CS1711 carried two β-lactamase genes, blaPER-1 and blaCTX-M-9. The location of antimicrobial resistance genes was identified by hybridization of I-CeuI-digested genomic DNA or S1 nuclease-treated linearized plasmids with probes specific for the β-lactamase genes, various replicons of plasmids, and 16S rRNA genes as described previously (16). Clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa (n = 8) and A. baumannii (n = 14), which were recovered from clinical samples of patients hospitalized at the same hospital during May and June 2006, carrying the blaPER-1 gene were included in this study for comparison. The blaPER-1 and the blaCTX-M-9 genes in K. pneumoniae strain CS1711 were located on the ∼150-kbp IncA/C plasmid (pCS1711 in transconjugant E. coli trcCS1711). However, the probe specific for the blaPER-1 gene did not hybridize with any plasmids in 8 P. aeruginosa isolates and 14 A. baumannii isolates. The probe hybridized with I-CeuI macrorestriction fragments of ∼500 kbp and ∼800 kbp in P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii isolates, respectively. The probe specific for 16S rRNA genes also hybridized with the I-CeuI macrorestriction fragments, indicating chromosomal location of the blaPER-1 gene in those P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii isolates.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in PCR and sequencing studies for antimicrobial resistance genes

| Target gene(s) | Primer name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Position in Fig. 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| blaTEM | TEM-F | TCCGCTCATGAGACAATAACC | |

| cluster | TEM-R | ACGCTCAGTGGAACGAAAAC | |

| blaSHV | SHV-F | CGCCGGGTTATTCTTATTTG | |

| cluster | SHV-R | CCACGTTTATGGCGTTACCT | |

| blaVEB | VEB-F | AAAATGCCAGAATAGGAGTAGCA | |

| cluster | VEB-R | TCCACGTTATTTTTGCAATGTC | |

| blaGES | GES-F | CGCTTCATTCACGCACTATT | |

| cluster | GES-R | GTCCGTGCTCAGGATGAGTT | |

| blaCTX-M-1 | CTX-M-1F | CCGTCACGCTGTTGTTAGG | |

| cluster | CTX-M-1R | ACGGCTTTCTGCCTTAGGTT | |

| blaCTX-M-9 | CTX-M9-F | CAAAGAGAGTGCAACGGATG | |

| cluster | CTX-M9-R | CCTTCGGCGATGATTCTC | |

| blaPER-1 | PER-F | CCTGACGATCTGGAACCTTT | 1 |

| cluster | PER-R | TGGTCCTGTGGTGGTTTC | 2 |

| ISPa12 gene | ISPa12-F | AAGCCCTGTTTTCAGAGCAA | 3 |

| ISPa12-R | AATCAACGTTTCGGCTATCG | 4 | |

| ISPa12-mF | GCCGATGCAGGTTATTTTTC | 5 | |

| ISPa12-wR | TCATGATTCATATGTGATTTCCAA | 6 | |

| ISPa13 gene | ISPa13-F | TTTTCAGCAGCAGAGCTTGA | 7 |

| ISPa13-R | CGTTGATTAGCCAGCGTTTT | 8 | |

| ISPa13-mF | TGATAAAGAGGCGGGTGAAG | 9 | |

| ISPa13-wR | TTTACGCCTCATAGGTATGATCTTTAG | 10 | |

| gst gene | GST-F | CCCCTTTTGTTCGTCGTTTA | 11 |

| GST-R | AAGGAGTCTGTGCAGGCATT | 12 |

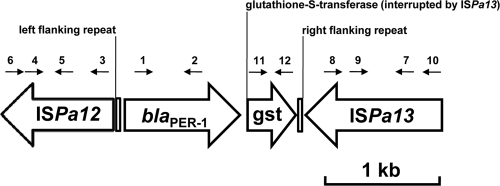

To investigate genetic environments surrounding the blaPER-1 gene, sequencing experiments of several overlapping PCR fragments obtained from whole DNA of the K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, and P. aeruginosa isolates with primers corresponding to internal region of Tn1213 were performed as previously described (15). Identically to the results for the blaPER-1 gene located on the chromosome in P. aeruginosa RNL-1 (GenBank accession no. AY779042), ISPa12 and ISPa13 elements were present upstream and downstream of the blaPER-1 gene, respectively, in all the isolates studied. The blaPER-1 gene located on a plasmid in two Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolates and in strain A. baumannii C.A. has been reported to be preceded by ISPa12 but not followed by ISPa13, while the blaPER-1 gene located on the plasmid pCS1711 was surrounded by both ISPa12 and ISPa13 elements (4, 14, 15) (Fig. 1). Our results suggest that the blaPER-1 gene in K. pneumoniae strain CS1711 might be mobilized from blaPER-1 gene-carrying A. baumannii or P. aeruginosa, since the genetic environments of the gene in those strains were identical.

FIG. 1.

Genetic environment of the blaPER-1 gene in K. pneumonia CS1711. Numbered arrows indicate positions and directions of the primers used in this study as listed in Table 2.

This report shows further dissemination of the blaPER-1 gene into Enterobacteriaceae and is the first report of K. pneumoniae carrying the blaPER-1 gene.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a faculty research grant of Yonsei University College of Medicine for 2010 (6-2010-0060).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bae, I. K., et al. 2006. A novel ceftazidime-hydrolysing extended-spectrum β-lactamase, CTX-M-54, with a single amino acid substitution at position 167 in the omega loop. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:315-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahar, G., B. Eraç, A. Mert, and Z. Gülay. 2004. PER-1 production in a urinary isolate of Providencia rettgeri. J. Chemother. 16:343-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bermudes, H., et al. 1999. Molecular characterization of TEM-59 (IRT-17), a novel inhibitor-resistant TEM-derived β-lactamase in a clinical isolate of Klebsiella oxytoca. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1657-1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casin, I., B. Hanau-Berçot, I. Podglajen, H. Vahaboglu, and E. Collatz. 2003. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium blaPER-1-carrying plasmid pSTI1 encodes an extended-spectrum aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase of type Ib. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:697-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2007. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; seventeenth informational supplement. M100-17. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 6.Litake, G. M., V. S. Ghole, K. B. Niphadkar, and S. G. Joshi. 2009. PER-1-type extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates from India. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34:388-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naas, T., et al. 2006. Emergence of PER and VEB extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Acinetobacter baumannii in Belgium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:178-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naas, T., S. Kernbaum, S. Allali, and P. Nordmann. 2007. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, Russia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:669-671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordmann, P., et al. 1993. Characterization of a novel extended-spectrum β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:962-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pagani, L., et al. 2004. Multifocal detection of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing the PER-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase in Northern Italy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2523-2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pagani, L., et al. 2002. Emerging extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Proteus mirabilis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1549-1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira, M., et al. 2000. PER-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase production in an Alcaligenes faecalis clinical isolate resistant to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and monobactams from a hospital in Northern Italy. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picão, R. C., et al. 2008. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in Aeromonas allosaccharophila recovered from a Swiss lake. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:948-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poirel, L., et al. 1999. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing strain of Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from a patient in France. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:157-158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poirel, L., L. Cabanne, H. Vahaboglu, and P. Nordman. 2005. Genetic environment and expression of the extended-spectrum β-lactamase blaPER-1 gene in Gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1708-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 17.Sirot, D. L., et al. 1992. Resistance to cefotaxime and seven other β-lactams in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae: a 3-year survey in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:1677-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vahaboglu, H., et al. 1995. Resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, caused by PER-1 β-lactamase, in Salmonella typhimurium from Istanbul, Turkey. 43:294-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vahaboglu, H., et al. 1997. Widespread detection of PER-1-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases among nosocomial Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in Turkey: a nationwide multicenter study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2265-2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, H., et al. 2007. Molecular epidemiology of clinical isolates of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. from Chinese hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4022-4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamano, Y., et al. 2006. Occurrence of PER-1-producing clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Japan and their susceptibility to doripenem. J. Antibiot. 59:791-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yong, D., et al. 2003. High prevalence of PER-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Acinetobacter spp. in Korea. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1749-1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]