Abstract

The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy and safety of tigecycline, a newly developed glycylcycline antibiotic, with those of empirical antibiotic regimens which have been reported to possess good efficacy for complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSIs), complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAIs), community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), and other infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) identified in PubMed, the Cochrane Library, and Embase was performed. Eight RCTs involving 4,651 patients were included in the meta-analysis. Compared with therapy with empirical antibiotic regimens, tigecycline monotherapy was associated with similar clinical treatment success rates (for the clinically evaluable [CE] population, odds ratio [OR] = 0.92, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.76 to 1.12, P = 0.42; for the clinical modified intent-to-treat [c-mITT] population, OR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.74 to 1.01, P = 0.06) and similar microbiological treatment success rates (for the microbiologically evaluable [ME] population, OR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.69 to 1.07, P = 0.19). The incidence of adverse events in the tigecycline group was significantly higher than that in the other therapy groups with a statistical margin (for the modified intent-to-treat [mITT] population, OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.17 to 1.52, P < 0.0001), especially in the digestive system (mITT population, OR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.67 to 3.46, P < 0.00001). No difference regarding all-cause mortality and drug-related mortality between tigecycline and the other regimens was found, although numerically higher mortality was found in the tigecycline group. This meta-analysis provides evidence that tigecycline monotherapy may be used as effectively as the comparison therapy for cSSSI, cIAIs, CAP, and infections caused by MRSA/VRE. However, because of the high risk of mortality, AEs, and emergence of resistant isolates, prudence with the clinical use of tigecycline monotherapy in infections is required.

The threat of antimicrobial resistance has been identified as one of the major challenges facing public health, and antimicrobial resistance has increased rates of morbidity and mortality and socioeconomic costs. The rapid rate of microbial evolution underscores the urgent need for development of new agents that overcome existing mechanisms of resistance displayed by multidrug-resistant bacteria.

Tigecycline is a first-in-class expanded-broad-spectrum glycylcycline. It inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit but with a five times higher affinity than that for the tetracyclines (4). In vitro studies demonstrate that it has good activity against many commonly encountered respiratory bacteria, including multiple resistant Gram-positive, Gram-negative, anaerobic, as well as multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (PRSP), and β-lactamase-producing Haemophilus influenzae, among others (5). Tigecycline overcomes the two key tetracycline resistance mechanisms (efflux pumps and ribosomal protection) and is unaffected by other bacterial mechanisms of resistance, such as extended-spectrum β-lactamases (32).

Tigecycline was first approved for use for indications of complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSIs) and complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAIs). Currently, it is approved for use for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). It has also been found to be effective for the treatment of hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia and bacteremia, sepsis with shock, and urinary tract infections.

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have compared tigecycline and other antibiotics for the treatment of infectious disease. The results mainly suggest that tigecycline is at least as effective as other therapies. However, these results were not completely consistent and did not necessarily justify that tigecycline was as effective as other therapies. Some reviews also discussed the efficacy and safety of tigecycline; however, they have limitations because without statistical evaluation of the literature, biases in the conclusions probably exist. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis of RCTs to clarify whether the use of tigecycline could be associated with improved outcomes in comparison with those achieved with other antibiotics for the treatment of infections, including cSSSIs, cIAIs, CAP, and infections caused by MDR pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources.

A systematic search of the literature in PubMed (up to November 2010), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Cochrane Library, issue 3, 2010), and Embase (1980 to November 2010) was conducted to identify relevant RCTs for our meta-analysis. The terms used for the search strategy were “tigecycline,” “glycylcycline,” “infection,” “skin and soft tissue infection,” “intra-abdominal infection,” “pneumonia,” “bacteremia,” “sepsis,” and “urinary tract infection.” Searches were limited to RCTs only. In addition, the references of the initially identified articles, including relevant review papers, were hand searched and reviewed. Abstracts presented in scientific conferences were not searched for.

Study selection.

Two reviewers (Y.C. and R.W.) independently searched the literature and examined relevant RCTs for further assessment of data on efficacy and safety. A study was considered eligible if it was a clinical RCT; if it studied the role of tigecycline in comparison with that of other antibiotics in the treatment of infections caused by Gram-positive, Gram-negative, anaerobic, or atypical bacteria; and if it assessed the efficacy, safety, or mortality for both therapeutic regimens. Hospital admission of patients was required for eligibility. Experimental trials and trials focusing on pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic variables were excluded.

Data extraction.

The following data were extracted from each study: (i) year of publication, (ii) patient population, (iii) number of patients, (iv) antimicrobial agents and dosages used, (v) clinical and microbiological outcomes, (vi) adverse effects (AEs), and (vii) mortality.

The intent-to-treat (ITT) population consists of patients who were initially screened for enrollment in the studies, who met the eligibility criteria, and who were randomly assigned to treatment. Patients who received at least one dose of study medication constituted the modified ITT (mITT) population. Patients in the mITT population who had clinical evidence of disease by meeting minimal disease criteria comprised the clinical mITT (c-mITT) population. The microbiological mITT (m-mITT) population consisted of patients in the c-mITT population who had one isolate identified at the baseline. The clinically evaluable (CE) population consisted of c-mITT patients who did not have Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a baseline primary isolate (tigecycline has no effect on Pseudomonas aeruginosa), who did not receive concomitant antibiotics after the first dose of tigecycline, and who met criteria for either clinical cure or failure at the test-of-cure (TOC) visit. The microbiologically evaluable (ME) population consisted of CE patients who had an identifiable primary isolate(s) that was susceptible to tigecycline and the comparator drugs and who had clinical and microbiological outcomes (i.e., eradication, persistence, or superinfection) at the TOC visit.

Qualitative assessment.

The two reviewers (Y.C. and R.W.) independently extracted the relevant data. A quality review of each RCT was done to include details of randomization, generation of random numbers, details of the double-blinding procedure, information on withdrawals, and allocation concealment. One point was awarded for the specification of each criterion, with the maximum score being 5. High-quality RCTs scored 3 or more points, whereas low-quality RCTs scored 2 or fewer points, according to a modified Jadad score (24).

Analyzed outcomes.

The primary efficacy outcome of this meta-analysis was clinical treatment success (defined as complete resolution or substantial improvement of symptoms and signs of CAP, cSSSIs, cIAIs, and other infections or no further antimicrobial therapy and surgical intervention for infection being necessary), assessed at the TOC visit employed in each individual study. The secondary efficacy outcomes were microbiological treatment success (defined as the eradication of baseline pathogens or as presumed eradication on the basis of the clinical outcomes when posttreatment cultures were not performed) and mortality. Outcomes on effectiveness were analyzed in the following groups: (i) patients with CAP, cSSSIs, cIAIs, and other infections and (ii) patients in the c-mITT and CE populations. Microbiological assessment and eradication (documented or presumed) were based on ME populations. AEs and mortality were based on m-ITT populations.

Data analysis and statistical methods.

Statistical analysis was done with the Review Manager program, version 5.0.17 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom). We assessed the heterogeneity of trial results by calculating a chi-square test of heterogeneity and the I2 measure of inconsistency. The publication bias was assessed by examining the funnel plot. We used a Mantel-Haenszel fixed-effect model (FEM) for pooling odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all primary and secondary outcomes (including the m-ITT, c-mITT, CE, and ME populations) throughout the meta-analysis, unless statistically significant heterogeneity was found (P < 0.10 or I2 > 50%), in which case we chose a DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model (REM). Heterogeneity was investigated through subgroup analysis, as defined above.

RESULTS

Selected randomized controlled trials.

Of 33 potentially relevant articles, 19 articles were excluded because they lacked a randomized control design. Four articles were excluded because they were part of other RCTs already included in this meta-analysis (e.g., data from European study sites that participated in a larger trial) (12, 17, 30, 44). Another two articles were excluded because they were combinations of RCTs already included in this meta-analysis (18, 42). Thus, eight RCTs were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram of the RCTs reviewed.

The main characteristics of the analyzed RCTs are shown in Table 1. The mean quality score of the included RCTs was 3.88 (range, 3 to 5). The quality of all the RCTs was high (scores, ≥3). A high Jadad score indicated the high quality of the RCTs included in the meta-analysis. All of the included RCTs were performed exclusively with adult patients (three RCTs involved patients with cIAIs, and two of those compared tigecycline with imipenem-cilastatin and the other one compared tigecycline with ceftriaxone plus metronidazole; two RCTs involved patients with cSSSIs and compared tigecycline with vancomycin and aztreonam; two RCTs involved patients with CAP and compared tigecycline with levofloxacin; and one RCT involved patients with MRSA or VRE infections and compared tigecycline with vancomycin or linezolid). Six RCTs had double-blind designs, while two RCTs were open label. We examined the funnel plot (standard error SE of log OR plotted against ORs) to estimate publication bias, showing a symmetric inverse funnel distribution.

TABLE 1.

Main characteristics of the trials included in the meta-analysisa

| Authors (reference) | RCT study design | Population | Drug regimen |

No. of patients enrolled | No. of patients in tigecycline group vs no. of patients in comparator group |

Study quality score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tigecycline | Comparator | ITT | m-ITT | c-mITT | CE | m-mITT | ME | |||||

| Babinchak et al. (2) | MC, DB, phase III | Patients ≥18 yr old requiring a surgical procedure for cIAI | 100-mg i.v. infusion over 30 min, followed by 50 mg i.v. q12h | Imipenem-cilastatin at 500 mg/500 mg i.v. q6h or dose adjusted on the basis of wt and creatinine clearance or according to local data sheet | 1,759 | 826 vs 832 | 817 vs 825 | 801 vs 800 | 685 vs 697 | 631 vs 631 | 512 vs 513 | 4 |

| Bergallo et al. (3) | MC, DB, phase III | Patients ≥18 yr old with CAP | 100 mg i.v., followed by 50 mg q12h | Levofloxacin at 500 mg i.v. q24h for creatinine clearance rates of at least 50 ml/min | 442 | 212 vs 213 | 208 vs 210 | 191 vs 203 | 138 vs 156 | 100 vs 115 | 75 vs 93 | 4 |

| Breedt et al. (6) | MC, DB, Phase III | Patients ≥18 yr old with cSSSI | 100 mg i.v., followed by 50 mg twice a day | 1 g vancomycin i.v. over 60 min, plus 2 g aztreonam over 60 min twice a day | 557 | 275 vs 271 | 274 vs 269 | 261 vs 259 | 223 vs 213 | 209 vs 203 | 164 vs 148 | 3 |

| Chen et al. (7) | MC, OL, phase III | Patients ≥18 yr old with known or suspected diagnosis of cIAI | 100-mg i.v. infusion over 30 min, followed by i.v. 50 mg q12h | Imipenem-cilastatin at 500 mg/500 mg i.v. q6h or dose adjusted on the basis of wt and creatinine clearance | 203 | 99 vs 104 | 97 vs 102 | 97 vs 98 | 77 vs 87 | 60 vs 55 | 52 vs 48 | 3 |

| Florescu et al. (16) | MC, DB, phase III | Patients ≥18 yr old infected with MRSA or VRE | 100 mg i.v., followed by 50 mg q12h | For MRSA infection, vancomycin at 1 g i.v. q12h | — | 118 vs 39 | 117 vs 39 | 100 vs 33 | 86 vs 31 | 100 vs 33 | 86 vs 31 | 5 |

| MC, DB, phase III | Patients ≥18 yr old infected with MRSA or VRE | 100 mg i.v., followed by 50 mg q12h | For VRE infection, linezolid at 600 mg i.v. q12h | — | 11 vs 4 | 11 vs 4 | 8 vs 3 | 3 vs 3 | 8 vs 3 | 3 vs 3 | 5 | |

| Sacchidanand et al. (35) | MC, DB, phase III | Patients ≥18 yr old with cSSSI | 100 mg i.v., followed by 50 mg twice a day | 1 g vancomycin i.v. over 60 min, plus 2 g aztreonam over 60 min twice a day | 596 | 295 vs 288 | 292 vs 281 | 277 vs 260 | 199 vs 198 | 186 vs 171 | 115 vs 113 | 4 |

| Tanaseanu et al. (42) | MC, DB, phase III | Patients ≥18 yr old with CAP | 100-mg infusion over 60 min, followed by 50 mg i.v. q12h | Levofloxacin at i.v. 500 mg once/twice a day; for creatinine clearance rate of 20-49 ml/min, 500 mg i.v., followed by 250 mg once/twice a day | 449 | 220 vs 214 | 216 vs 212 | 203 vs 200 | 144 vs 136 | 125 vs 117 | 91 vs 86 | 5 |

| Towfigh et al. (45) | MC, OL, phase IIIb/IV | Patients with a known or suspected diagnosis of cIAI | 100-mg infusion i.v. over 30 min, followed by 50 mg i.v. q12h | Ceftriaxone at 2 g i.v. once daily plus metronidazole at 1-2 g daily given in divided doses | 473 | 237 vs 236 | 236 vs 231 | 228 vs 220 | 189 vs 187 | 163 vs 158 | 138 vs 137 | 3 |

Abbreviations and symbols: DB, double blind; MC, multicenter; OL, open label; i.v., intravenous; q12h, every 12 h; —, not available.

Treatment success in CE and c-mITT patients.

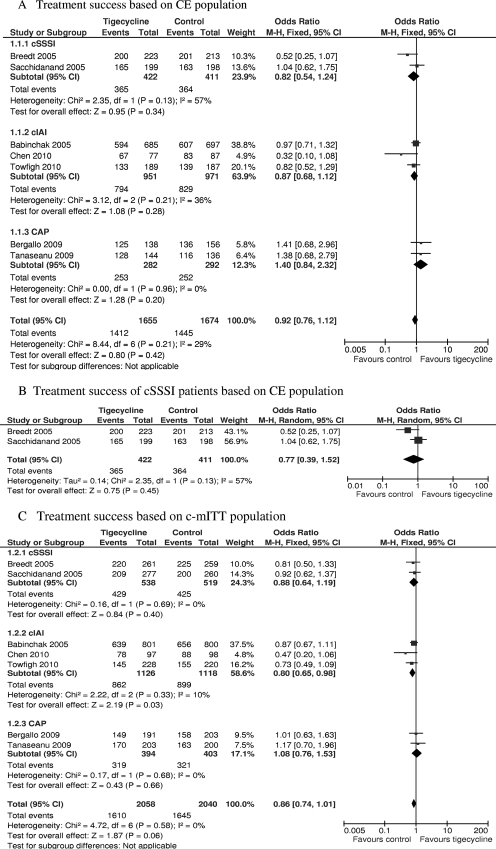

Data regarding the success of treatment with the administered antimicrobial regimens for CE and c-mITT patients were reported in seven RCTs (2, 3, 6, 7, 35, 43, 45). The treatment success of one RCT (16) was based on ME and m-mITT populations, so it was not included here. There was no significant difference in treatment success in the CE population between patients treated with tigecycline and those treated with comparators (3,329 patients, FEM, OR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.76 to 1.12, P = 0.42, Fig. 2A). The same was true for c-mITT patients (4,098 patients, FEM, OR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.74 to 1.01, P = 0.06, Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Meta-analysis of treatment success based on CE and c-mITT populations. df, degrees of freedom; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel method.

Regarding the cSSSI, cIAI, and CAP subgroups, there was also no significant difference in treatment success at the TOC visit between the CE patients treated with tigecycline and those treated with comparators (for two RCTs with the cSSSI subgroup, 833 patients, REM, OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.39 to 1.52, P = 0.45, Fig. 2B; for three RCTs with the cIAI subgroup, 1,922 patients, FEM, OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.68 to 1.12, P = 0.28, Fig. 2A; for the CAP subgroup, 574 patients, FEM, OR = 1.40, 95% CI = 0.84 to 2.32, P = 0.20, Fig. 2A). The conservative c-mITT analysis of the cSSSI and CAP subgroup confirmed the above results (for the cSSSI subgroup, 1,057 patients, FEM, OR = 0.88, 95% CI = 0.64 to 1.19, P = 0.40; for the CAP subgroup, 797 patients, FEM, OR = 1.08, 95% CI = 0.76 to 1.53, P = 0.66; Fig. 2C). However, the success of tigecycline treatment in the cIAI subgroup was significantly lower than that in the comparator groups (2,244 patients, FEM, OR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.65 to 0.98, P = 0.03, Fig. 2C).

Microbiological treatment success in ME patients.

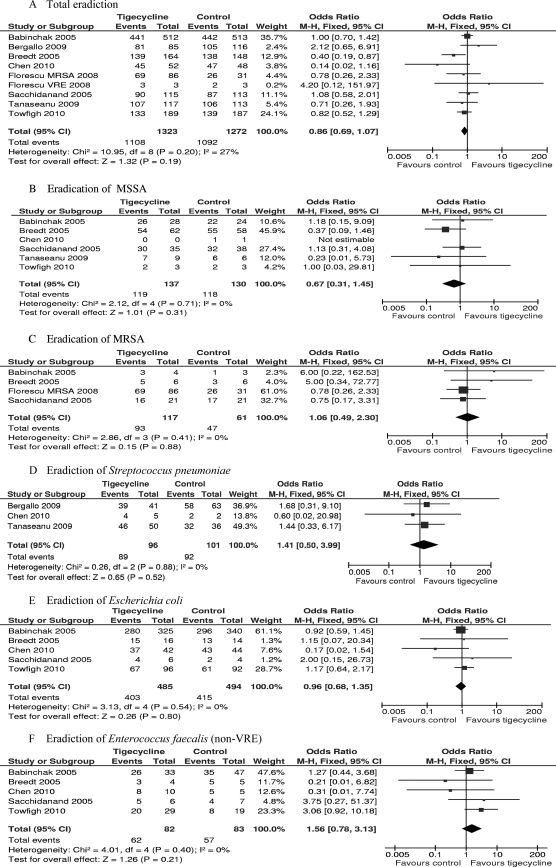

All eight RCTs included in the meta-analysis reported data on ME patients. In our meta-analysis, the study of Florescu et al. (16) was split according to the bacterial pathogen because two comparator drugs were used according to different pathogens. The total microbiological treatment success for the tigecycline group was numerically lower than that for the comparator group in the ME population at the TOC visit, but there was no significant difference (2,595 patients, FEM, OR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.69 to 1.07, P = 0.19, Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Meta-analyses of pathogen eradication in total and for MSSA, MRSA, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus faecalis (non-VRE) for ME population. df, degrees of freedom; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel method.

More specifically, treatment with tigecycline was associated with numerically higher eradication rates for MRSA, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Enterococcus faecalis (non-VRE) (for MRSA, 178 strains, FEM, OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.49 to 2.30, P = 0.88, Fig. 3C; for S. pneumoniae, 197 strains, FEM, OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 0.50 to 3.99, P = 0.52, Fig. 3D; for E. faecalis, 165 strains, FEM, OR = 1.56, 95% CI = 0.78 to 3.13, P = 0.21, Fig. 3F). Treatment with tigecycline was associated with numerically lower eradication rates for methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and Escherichia coli (for MSSA, 267 strains, FEM, OR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.31 to 1.45, P = 0.31, Fig. 3B; for E. coli, 979 strains, FEM, OR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.68 to 1.35, P = 0.80, Fig. 3E). However, there were no significant differences in eradication for all these species.

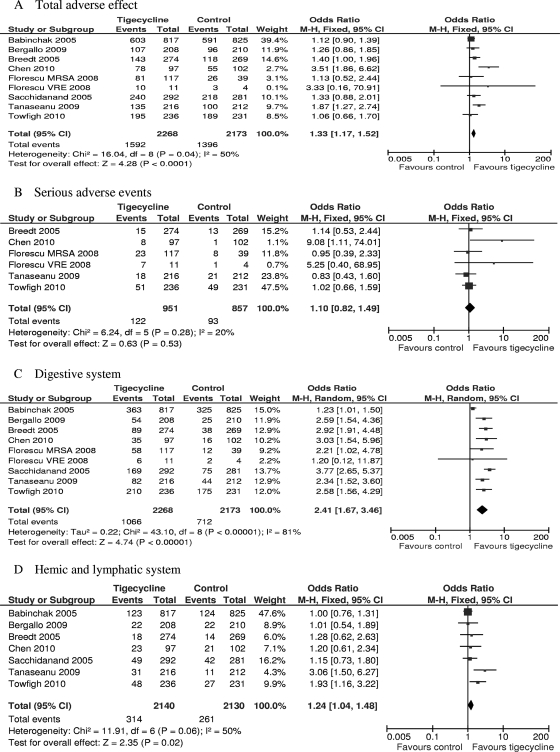

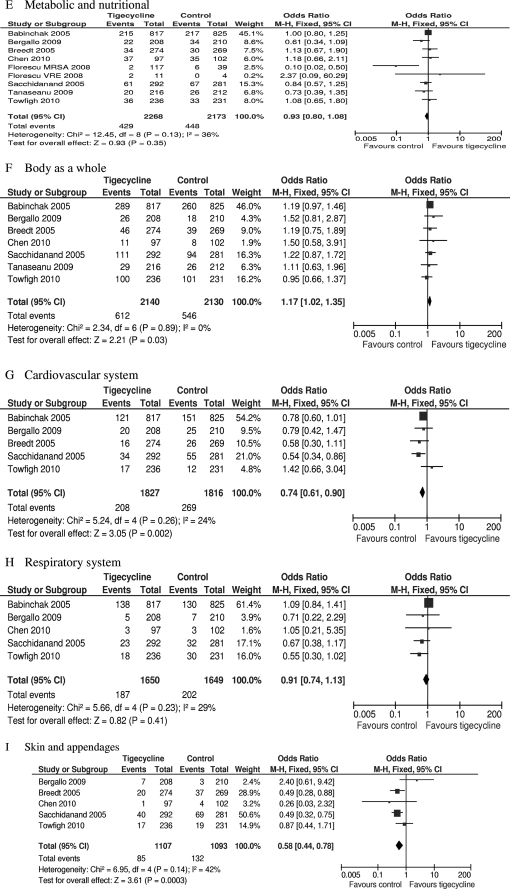

Adverse effects.

Data on AEs possibly or probably related to the study medications were reported for all included trials. Three trials did not report the severe AEs (SAEs) and were therefore excluded from the analysis of SAEs (2, 3, 35). The total numbers of adverse events in the tigecycline groups were significantly higher than the numbers in the comparators in the mITT population (eight RCTs, mITT population, 4,441 patients, FEM, OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.17 to 1.52, P < 0.0001, Fig. 4A). There was no difference in SAEs (five RCTs, mITT population, 1,808 patients, FEM, OR = 1.10, 95% CI = 0.82 to 1.49, P = 0.53, Fig. 4B). Significantly more episodes of AEs in the digestive system, hemic and lymphatic system, and body as a whole were reported in tigecycline-treated patients (eight RCTs, mITT population, 4,441 patients, REM, OR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.67 to 3.46, P < 0.00001, Fig. 4C; seven RCTs, mITT population, 4,270 patients, FEM, OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.04 to 1.48, P = 0.02, Fig. 4D; seven RCTs, mITT population, 4,270 patients, FEM, OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.02 to 1.35, P = 0.03, Fig. 4F). Significantly fewer episodes of AEs in the cardiovascular system and skin/appendages were reported in the tigecycline groups (five RCTs, mITT population, 3,643 patients, FEM, OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.61 to 0.90, P = 0.02, Fig. 4G; five RCTs, mITT population, 2,200 patients, FEM, OR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.44 to 0.78, P = 0.0003, Fig. 4I). There was no significant difference in the proportions of patients who developed AEs in the metabolic and nutritional system and respiratory system between the compared regimens (eight RCTs, mITT population, 4,441 patients, FEM, OR = 0.93, 95% = CI 0.80 to 1.08, Fig. 4E; five RCTs, mITT population, 3,299 patients, FEM, OR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.74 to 1.13, Fig. 4H).

FIG. 4.

Meta-analyses of adverse effects probably or possibly related to studied medications. df, degrees of freedom; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel method.

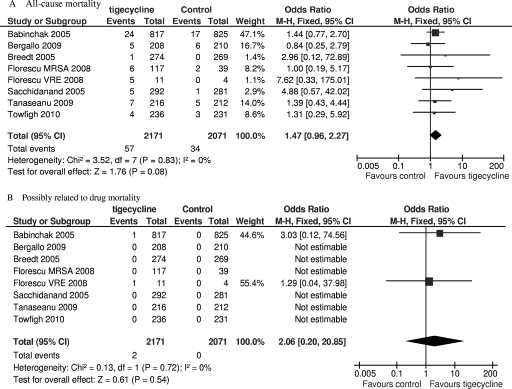

Mortality.

All-cause mortality and mortality possibly related to the study drug during the study period were available in seven of the eight included trials. Although numerically higher mortality in the tigecycline groups can be seen, there was no significant difference in mortality between the tigecycline and comparator groups (mITT population, 4,242 patients, FEM, OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 0.96 to 2.27, P = 0.08, Fig. 5A; mITT population, 4,242 patients, FEM, OR = 2.06, 95% CI = 0.20 to 20.85, P = 0.54, Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Meta-analyses of all-cause mortality and mortality possibly related to study drug. df, degrees of freedom; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel method.

DISCUSSION

The results of the current meta-analysis suggest that tigecycline is as clinically effective as vancomycin and aztreonam for cSSSIs, imipenem-cilastatin, or ceftriaxone plus metronidazole for cIAIs and levofloxacin for CAP in both CE and c-mITT populations. Although tigecycline treatment showed no significant difference in eradiation rate from that for the comparator groups for almost all types of pathogens, we can find better eradication rates for MRSA, S. pneumoniae, and E. faecalis (non-VRE) than for MSSA and E. coli. Several clinical trials also confirmed tigecycline's efficacy. Grolman (20) showed that tigecycline was shown to be noninferior to combination vancomycin-aztreonam regimens and exhibited high clinical success rates for cSSSIs. In a noncomparative study, tigecycline appeared to be safe and efficacious in patients with difficult-to-treat serious infections caused by resistant Gram-negative organisms, the clinical cure rate was 72.2%, and the microbiological eradication rate was 66.7% (46). Many other case series and case reports have revealed the success of treatment with tigecycline against MDR isolates, such as MRSA (27, 29), Acinetobacter spp. (10, 37, 41, 47), Klebsiella pneumoniae (8, 11, 14), Klebsiella pneumoniae causing meningitis (48), VRE (25, 36), E. coli (28, 40), and Clostridium difficile (21), although in some of these studies tigecycline was combined with other antibiotics, such as colistin (8, 37, 38), daptomycin (25), and ciprofloxacin (48). However, recent several articles (1, 33) reported on the emergence of tigecycline-resistant strains after tigecycline therapy. Cui et al. (9) suggest that tigecycline concentrations would fall between the MIC and the mutant prevention concentration (MPC) for most of the entire dosing period, so this compound may be prone to the emergence of resistance when it is used with A. baumannii. Taken together, tigecycline is an efficacious antibiotic in infected patients, especially for those infected by MDR pathogens, and prudence is required when it is used alone against infections caused by nonresistant strains.

From this meta-analysis, tigecycline regimens had a significantly increased incidence of total AEs. The numbers of AEs related to the digestive system in the tigecycline treatment group were much higher than those in the comparator groups. An increased incidence of AEs in the hemic and lymphatic system and the body as a whole (including fever, headache, infection, abdominal pain, chills, and pain) were also found in tigecycline-treated patients. Nausea and diarrhea were also confirmed to be the adverse drug reactions most often reported in both healthy volunteers and clinically infected patients in many other studies of tigecycline treatment (14, 25, 31, 34, 46). The possibility of tigecycline-induced acute pancreatitis has recently been raised (19, 23) and has also been associated with the tetracycline class of antibiotics. Therefore, it is strongly recommended that clinicians monitor their patients for signs and symptoms of digestive system AEs during treatment with tigecycline.

Although the rate of mortality from the tigecycline regimen was numerically higher than that from the comparator regimens for both all-cause mortality and mortality possibly related to the study drug in our meta-analysis, the difference was not significant. However, an FDA Drug Safety Communication (1 September 2010) reminded health care professionals of the increased mortality risk associated with the use of the intravenous antibacterial tigecycline compared to that associated with the use of other drugs used to treat a variety of serious infections. Death occurred in 4.0% (150/3,788) of patients receiving tigecycline, whereas it occurred in 3.0% (110/3,646) of patients receiving other antibiotics, with the adjusted risk difference of all-cause mortality being 0.6% (95% CI = 0.1 to 1.2) (15). The difference in the rates of mortality between our meta-analysis and the FDA report is mainly due to unpublished data on the use of tigecycline to treat hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP). Particularly high mortality was seen among patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) when they were treated with tigecycline (25/131 [19.1%] versus 15/122 [12.3%] for the comparator group) (15). Taking into account the increased risk of all-cause mortality in patients with certain severe infections, clinicians need to fully consider the benefit and risk of tigecycline before its prescription.

Although the present evidence suggests that tigecycline has a similar efficacy as comparator agents, several unique characteristics make it an alternative to existing regimens. First, tigecycline has a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, ranging from aerobic to anaerobic, Gram-positive, and Gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, it has an excellent effect against MRSA, VRE, drug-resistant S. pneumoniae, and respiratory Gram-negative pathogens, such as H. influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. This is quite important for severe infections caused by mixed pathogens. For example, tigecycline might be the only monotherapy strategy for infections caused by MRSA mixed with MDR Gram-negative strains. So the empirical use of tigecycline for cSSSIs and cIAIs seems attractive, because in those settings, the likely pathogens often include both Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains. Second, tigecycline is also active against atypical organisms (i.e., Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Legionella pneumophila), which are frequently isolated from patients who require hospitalization for CAP (49). So the antibiotic with a spectrum that includes atypical organisms might have better clinical effects. Our meta-analysis also indicates that tigecycline therapy showed better efficacy numerically than levofloxacin therapy. Third, no dosage adjustment of tigecycline is necessary in patients with renal insufficiency or mild to moderate hepatic impairment and the aged population, although in the population with severe hepatic impairment, the initial dose should be 100 mg, followed by a reduced maintenance dose of 25 mg every 12 h (13, 26). This may offer benefits over other antibiotics that have limitations for use by special populations, such as vancomycin.

The findings of the present study must be viewed in the context of potential limitations. First, the meta-analysis does not include all the RCTs on tigecycline, as we mentioned above for mortality. FDA reported on more RCTs than we included; however, we have no means to get the unpublished data. So the results of our meta-analysis were limited to studies of infections for which the use of tigecycline is currently approved: cSSSIs, cIAIs, and CAP. Second, the meta-analysis is based on a relatively small number of RCTs, and the limited number of studies raises the possibility of a second-order sampling error. However, meta-analyses often include small numbers of studies. One study evaluated 39 Cochrane reviews and found that 67% of them included ≤5 studies and 20% included ≤10 studies (22). What is more, a lower threshold for the number of studies to be included in a meta-analysis has not yet been established (39). Third, there is heterogeneity in some of the relevant aspects (the patients and comparative drugs included). Given this uncertainty resulting from clinical heterogeneity, subgroup analysis was performed on different patients and comparative drugs about treatment success. Finally, all of the eight included trials were supported by the branding pharmaceutical company of tigecycline, a factor that might generate bias in the assessment of outcomes.

In conclusion, despite the limitations of our meta-analysis, we conclude that tigecycline monotherapy has clinical efficacy and microbiological treatment success rates similar to those of comparator drugs for cSSSIs, cIAIs, and CAP. Tigecycline is associated with a greater risk of AEs than the comparators, especially in the digestive system. Tigecycline therapy may be a useful alternative to empirical treatment for cSSSIs, cIAIs, and CAP. However, health care professionals should be prudent when they use tigecycline in patients with severe infections because of the increased risk of mortality.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the authors of the primary studies, without whose contributions this work would not have been possible.

We have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical approval for this study was not required.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthony, K. B., et al. 2008. Clinical and microbiological outcomes of serious infections with multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms treated with tigecycline. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:567-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babinchak, T., et al. 2005. The efficacy and safety of tigecycline for the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections: analysis of pooled clinical trial data. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41(Suppl. 5):S354-S367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergallo, C., et al. 2009. Safety and efficacy of intravenous tigecycline in treatment of community-acquired pneumonia: results from a double-blind randomized phase 3 comparison study with levofloxacin. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 63:52-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergeron, J., et al. 1996. Glycylcyclines bind to the high-affinity tetracycline ribosomal binding site and evade Tet(M)- and Tet(O)-mediated ribosomal protection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2226-2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharya, M., A. Parakh, and M. Narang. 2009. Tigecycline. J. Postgrad. Med. 55:65-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breedt, J., et al. 2005. Safety and efficacy of tigecycline in treatment of skin and skin structure infections: results of a double-blind phase 3 comparison study with vancomycin-aztreonam. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4658-4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, Z., et al. 2010. Efficacy and safety of tigecycline monotherapy vs. imipenem/cilastatin in Chinese patients with complicated intra-abdominal infections: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 10:217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cobo, J., et al. 2008. Use of tigecycline for the treatment of prolonged bacteremia due to a multiresistant VIM-1 and SHV-12 beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae epidemic clone. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 60:319-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui, J. C., Y. N. Liu, and L. A. Chen. 2010. Mutant prevention concentration of tigecycline for carbapenem-susceptible and -resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 63:29-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curcio, D., F. Fernandez, J. Vergara, W. Vazquez, and C. M. Luna. 2009. Late onset ventilator-associated pneumonia due to multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter spp.: experience with tigecycline. J. Chemother. 21:58-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daly, M. W., D. J. Riddle, N. A. Ledeboer, W. M. Dunne, and D. J. Ritchie. 2007. Tigecycline for treatment of pneumonia and empyema caused by carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pharmacotherapy 27:1052-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dartois, N., N. Castaing, H. Gandjini, A. Cooper, and G. Tigecycline 313 Study. 2008. Tigecycline versus levofloxacin for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia: European experience. J. Chemother. 20(Suppl. 1):28-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doan, T. L., H. B. Fung, D. Mehta, and P. F. Riska. 2006. Tigecycline: a glycylcycline antimicrobial agent. Clin. Ther. 28:1079-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evagelopoulou, P., P. Myrianthefs, A. Markogiannakis, G. Baltopoulos, and A. Tsakris. 2008. Multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae mediastinitis safely and effectively treated with prolonged administration of tigecycline. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:1932-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.FDA. 2010. Drug safety announcement—tigecycline. FDA, Rockville, MD. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm224370.htm. Accessed 1 September 2010.

- 16.Florescu, I., et al. 2008. Efficacy and safety of tigecycline compared with vancomycin or linezolid for treatment of serious infections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or vancomycin-resistant enterococci: a phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, randomized study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62(Suppl. 1):i17-i28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fomin, P., et al. 2008. The efficacy and safety of tigecycline for the treatment of complicated intra-adominal infections—the European experience. J. Chemother. 20:12-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardiner, D., G. Dukart, A. Cooper, and T. Babinchak. 2010. Safety and efficacy of intravenous tigecycline in subjects with secondary bacteremia: pooled results from 8 phase III clinical trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:229-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilson, M., et al. 2008. Acute pancreatitis related to tigecycline: case report and review of the literature. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 40:681-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grolman, D. C. 2007. Therapeutic applications of tigecycline in the management of complicated skin and skin structure infections. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 11:S7-S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herpers, B. L., et al. 2009. Intravenous tigecycline as adjunctive or alternative therapy for severe refractory Clostridium difficile infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1732-1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins, J., S. Thompson, J. Deeks, and D. Altman. 2002. Statistical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of clinical trials: a critical appraisal of guidelines and practice. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 7:51-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung, W. Y., L. Kogelman, G. Volpe, M. Iafrati, and L. Davidson. 2009. Tigecycline-induced acute pancreatitis: case report and literature review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34:486-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jadad, A. R., et al. 1996. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin. Trials 17:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkins, I. 2007. Linezolid- and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium endocarditis: successful treatment with tigecycline and daptomycin. J. Hosp. Med. 2:343-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasbekar, N. 2006. Tigecycline: a new glycylcycline antimicrobial agent. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 63:1235-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khanna, N., and T. Inkster. 2008. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus hepatic abscess treated with tigecycline. J. Clin. Pathol. 61:967-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krueger, W. A., et al. 2008. Treatment with tigecycline of recurrent urosepsis caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:817-820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munoz-Price, L. S., K. Lolans, and J. P. Quinn. 2006. Four cases of invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections treated with tigecycline. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 38:1081-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliva, M. E., et al. 2005. A multicenter trial of the efficacy and safety of tigecycline versus imipenem/cilastatin in patients with complicated intra-abdominal infections [Study ID numbers: 3074A1-301-WW; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00081744]. BMC Infect. Dis. 5:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Passarell, J., et al. 2009. Exposure-response analyses of tigecycline tolerability in healthy subjects. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 65:123-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterson, L. R. 2008. A review of tigecycline—the first glycylcycline. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 32(Suppl. 4):S215-S222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reid, G. E., S. A. Grim, C. A. Aldeza, W. M. Janda, and N. M. Clark. 2007. Rapid development of Acinetobacter baumannii resistance to tigecycline. Pharmacotherapy 27:1198-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rello, J. 2005. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety and tolerability of tigecycline. J. Chemother. 17:12-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sacchidanand, S., et al. 2005. Efficacy and safety of tigecycline monotherapy compared with vancomycin plus aztreonam in patients with complicated skin and skin structure infections: results from a phase 3, randomized, double-blind trial. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 9:251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheetz, M. H., et al. 2006. Peritoneal fluid penetration of tigecycline. Ann. Pharmacother. 40:2064-2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sopirala, M. M., et al. 2008. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia in lung transplant recipients. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 27:804-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanzani, M., et al. 2007. Successful treatment of multi-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa osteomyelitis after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation with a combination of colistin and tigecycline. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:1692-1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sterne, J. A., and M. Egger. 2001. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 54:1046-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stumpf, A. N., C. Schmidt, W. Hiddemann, and A. Gerbitz. 2009. High serum concentrations of cyclosporin related to administration of tigecycline. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 65:101-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taccone, F. S., et al. 2006. Successful treatment of septic shock due to pan-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii using combined antimicrobial therapy including tigecycline. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 25:257-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaseanu, C., et al. 2008. Integrated results of 2 phase 3 studies comparing tigecycline and levofloxacin in community-acquired pneumonia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 61:329-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaseanu, C., et al. 2009. Efficacy and safety of tigecycline versus levofloxacin for community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Pulm. Med. 9:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teras, J., et al. 2008. Overview of tigecycline efficacy and safety in the treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections—a European perspective. J. Chemother. 20(Suppl. 1):20-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Towfigh, S., J. Pasternak, A. Poirier, H. Leister, and T. Babinchak. 2010. A multicentre, open-label, randomized comparative study of tigecycline versus ceftriaxone sodium plus metronidazole for the treatment of hospitalized subjects with complicated intra-abdominal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1274-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vasilev, K., et al. 2008. A phase 3, open-label, non-comparative study of tigecycline in the treatment of patients with selected serious infections due to resistant Gram-negative organisms including Enterobacter species, Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62(Suppl. 1):i29-i40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wadi, J. A., and M. A. Al Rub. 2007. Multidrug resistant Acinetobacter nosocomial meningitis treated successfully with parenteral tigecycline. Ann. Saudi Med. 27:456-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wadi, J. A., and F. Selawi. 2009. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase Klebsiella pneumoniae meningitis treated with tigecycline. Ann. Saudi Med. 29:239-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woodhead, M., et al. 2005. Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections. Eur. Respir. J. 26:1138-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]