Abstract

Streptococcus agalactiae UCN70, isolated from a vaginal swab obtained in New Zealand, is resistant to lincosamides and streptogramins A (LSA phenotype) and also to tiamulin (a pleuromutilin). By whole-genome sequencing, we identified a 5,224-bp chromosomal extra-element that comprised a 1,479-bp open reading frame coding for an ABC protein (492 amino acids) 45% identical to Lsa(A), a protein related to intrinsic LSA resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. Expression of this novel gene, named lsa(C), in S. agalactiae BM132 after cloning led to an increase in MICs of lincomycin (0.06 to 4 μg/ml), clindamycin (0.03 to 2 μg/ml), dalfopristin (2 to >32 μg/ml), and tiamulin (0.12 to 32 μg/ml), whereas no change in MICs of erythromycin (0.06 μg/ml), azithromycin (0.03 μg/ml), spiramycin (0.25 μg/ml), telithromycin (0.03 μg/ml), and quinupristin (8 μg/ml) was observed. The phenotype was renamed the LSAP phenotype on the basis of cross-resistance to lincosamides, streptogramins A, and pleuromutilins. This gene was also identified in similar genetic environments in 17 other S. agalactiae clinical isolates from New Zealand exhibiting the same LSAP phenotype, whereas it was absent in susceptible S. agalactiae strains. Interestingly, this extra-element was bracketed by a 7-bp duplication of a target site (ATTAGAA), suggesting that this structure was likely a mobile genetic element. In conclusion, we identified a novel gene, lsa(C), responsible for the acquired LSAP resistance phenotype in S. agalactiae. Dissection of the biochemical basis of resistance, as well as demonstration of in vitro mobilization of lsa(C), remains to be performed.

Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in neonates and pregnant women worldwide (14). It is also recognized as an emerging significant pathogen in nonpregnant adults, including elderly persons and patients with underlying conditions such as diabetes mellitus or immunosuppression (22). The clinical spectrum of S. agalactiae infection is broad and includes bacteremia, endocarditis, skin and soft tissue infections, respiratory and urinary tract infections, and joint and bone infections (23). Penicillin G and ampicillin represent the antimicrobial agents of choice for intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis during labor and for treating invasive infections caused by S. agalactiae (14, 23). For patients who are allergic to penicillin, the recommended alternative drugs are macrolides or lincosamides (21). However, although S. agalactiae remains universally susceptible to penicillins, there is a significant and rising resistance to macrolides and lincosamides in both invasive and colonizing strains in many parts of the world, with reported prevalence values ranging from 7 to 32% and from 2 to 15%, respectively (26).

Even if macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins (referred to as MLS) are chemically distinct, they are classified in the same group due to their similar mechanisms of action to inhibit protein synthesis and their cross-resistance due to target modification (15). Macrolides are classified according to the number of atoms forming the lactone ring: 14 (e.g., erythromycin), 15 (e.g., azithromycin), or 16 (e.g., spiramycin). Telithromycin is a semisynthetic erythromycin A derivative, belonging to the ketolide subgroup, with enhanced activity against macrolide-resistant streptococci. Lincosamides comprise two representatives (lincomycin and clindamycin), whereas streptogramins correspond to a mixture of two compounds which act synergistically: streptogramins A (e.g., dalfopristin) and streptogramins B (e.g., quinupristin). Finally, pleuromutilins (e.g., tiamulin) are also a class of protein synthesis inhibitors, mostly used in veterinary medicine, whose action and resistance mechanisms are similar to those of MLS (17).

In S. agalactiae, there are two major resistance mechanisms, namely, active efflux and target site modification (2, 5, 6, 8). The efflux pump is encoded by the mef(A) gene, whereas ribosomal alteration is mediated by a ribosomal methylase encoded by erm(B) and/or a specific erm(A) subtype formerly known as erm(TR). Expression of mef(A) confers resistance to 14- and 15-membered ring macrolides (M phenotype) only, whereas expression of erm(B) and/or erm(TR) is responsible for cross-resistance to all macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins B (MLSB phenotype), and this resistance can be expressed constitutively or inducibly (15).

An unusual phenotype of resistance to lincosamides and streptogramins A (called the LSA phenotype) has been reported for 19 S. agalactiae clinical isolates collected in New Zealand (16, 26) and has also been identified in Asia (12, 27). However, the biochemical and genetic basis of this resistance has not been elucidated yet. For these 19 strains, antibiotics did not seem to be inactivated or exported, while no known acquired resistance genes were present (16). Although no plasmid and no conjugative transfer of resistance were detected, acquisition of resistance by horizontal transfer was very likely, since S. agalactiae clones that were unrelated epidemiologically exhibited the same LSA phenotype (16). The aims of this study were (i) to identify the resistance determinant responsible for the LSA phenotype in S. agalactiae and (ii) to characterize the genetic support for this novel gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Nineteen S. agalactiae clinical isolates from New Zealand exhibiting an LSA phenotype were studied (16, 26). The S. agalactiae UCN70 isolate was recovered from a vaginal swab, while the other 18 clinical isolates were obtained from vaginal swabs (n = 8), urines (n = 2), and other sites (n = 8) (16). Thirteen isolates belonged to serotype III (including strain UCN70), five belonged to serotype I, and one was nontypeable, while each serotype corresponded to a unique type by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (genotypes A, B, and C) (16). Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 and S. agalactiae BM132 (9) were used as a control for antimicrobial susceptibility testing and as a recipient in transformation experiments, respectively.

MICs of erythromycin, azithromycin, spiramycin, telithromycin, lincomycin, clindamycin, quinupristin, dalfopristin, quinupristin-dalfopristin, and tiamulin were determined by the broth microdilution method (tested range, 0.01 to 32 μg/ml) according to CLSI guidelines (3).

Whole-genome sequencing.

Genomic DNA was extracted from mid-log-phase cultures of S. agalactiae UCN70 by use of NucleoBond buffer set III and a NucleoBond AX-G 100 instrument (Macherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) following the manufacturer's instructions. High-throughput sequencing was performed by using a 454 Life Sciences (Roche) GS-FLX system (GATC Biotech, Konstanz, Germany). Shotgun sequencing led to an assembly of 83 contigs of 513 to 148,170 bp, with an aggregate genome size of 2,136,339 bp and a 13.6× average coverage of the genome. The nucleotide and deduced protein sequences for each contig were analyzed with the BlastN and BlastX programs, available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

PCR amplification and sequencing.

Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted using an Instagen Matrix kit (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). PCR experiments for detection and mapping were carried out under standard conditions, using primers synthesized by Eurogentec France SAS (Table 1). Purified PCR products were then directly sequenced with the same sets of primers in both directions (GATC Biotech, Konstanz, Germany).

TABLE 1.

Deoxynucleotide primers used in this study

| Primera,b | Nucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′)c | Positiond | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| lsaC-Sa-F | GGCTATGTAAAACCTGTATTTG | 5234-5256 | Detection of lsa(C) |

| lsaC-Sa-R | ACTGACAATTTTTCTTCCGT | 5643-5663 | |

| lsaC-Sa-F-BamHI | ATCAGAGGATCCTGAAAAGTTAGG | 4664-4688 | Cloning of lsa(C) |

| lsaC-Sa-R-XbaI | ATCTTTTCTAGAATAGCATAAGG | 6719-6742 | |

| lsaC-Sa-dw-F1 (1) | GATACATATAGGTTTTTGGGG | 1623-1644 | PCR mapping of mobile element |

| lsaC-Sa-up-R1 (2) | GATAATTATATGACTTTTAGTCG | 7186-7209 | |

| lsaC-Sa-int-F1 (3) | GGACTGATATTACTTGTAGG | 2420-2440 | |

| lsaC-Sa-int-F2 (4) | GTTTAGAAATCTCTGAAATGG | 3402-3423 | |

| lsaC-Sa-int-F3 (5) | AAAGCAAGGTGATATAGTGG | 6187-6207 | |

| lsaC-Sa-int-R1 (6) | CATACGCAAGAAACAAAATGG | 2499-2520 | |

| lsaC-Sa-int-R2 (7) | TTATACGATAAGAACATAGAGG | 3522-3544 | |

| lsaC-Sa-int-R3 (8) | TCTACTGTTTCATCTTTCGG | 4734-4754 | |

| lsaC-Sa-GSP-R1 | CTTATAAACTTCTTGG | 5350-5366 | Determination of transcription start site |

| lsaC-Sa-GSP-R2 | AAATAGTGTTGATTTCCCAATTCCG | 5311-5336 | 5′-RACE |

| lsaC-Sa-GSP-R3 | CTATTAGTCCTGTTTTCCAGTTCG | 5280-5304 |

Sa, Streptococcus agalactiae; F, forward primer; R, reverse primer; dw, downstream; up, upstream; int, internal; GSP, gene-specific primer.

Numbers in parentheses indicate the locations of the primers in Fig. 1.

Restriction sites are underlined.

Primer positions were determined according to the nucleotide sequence deposited in GenBank (accession no. HM990671).

Cloning experiments.

The LSA resistance determinant and its putative promoter region were amplified by a PCR using primers modified to include BamHI and XbaI restriction sites (Table 1). The PCR fragment was then cloned into the shuttle vector pAT28 (25) in Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen, Cergy-Pontoise, France). Recombinant plasmids were then transformed by electroporation into S. agalactiae BM132 (9) electrocompetent cells, and transformants were selected on agar plates containing spectinomycin (180 μg/ml). The cloned DNA fragments of recombinant plasmids were sequenced on both strands by primer walking (GATC Biotech, Konstanz, Germany).

5′-RACE.

Total RNAs were extracted from cultures of S. agalactiae transformants by using an RNeasy Protect minikit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). The promoter sequences were then determined by using a 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE) kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, using different specific primers (Table 1).

Multiple alignment and phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis was performed by using the neighbor-joining algorithm, using the multiple alignment software ClustalX (version 1.83), and the resulting tree was displayed with TreeView software (version 1.6.6).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the lsa(C)-comprising genetic element has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. HM990671.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of a novel lsa(C) gene in S. agalactiae UCN70.

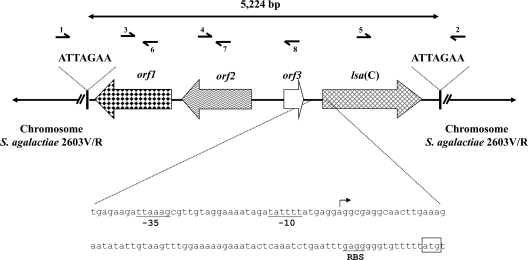

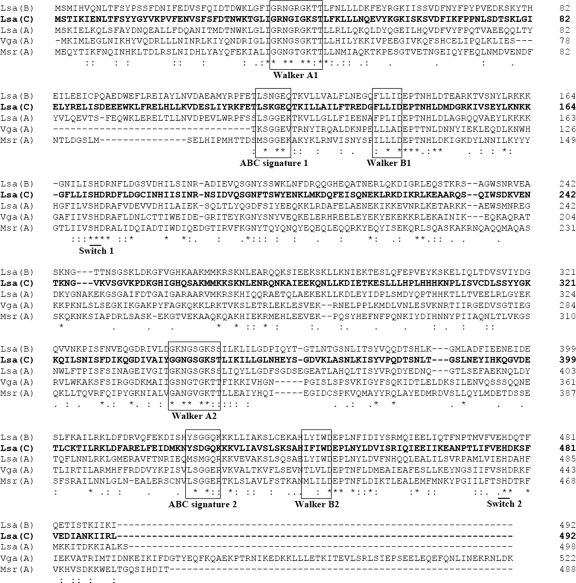

By comparison with genome sequences of S. agalactiae reference strains available in the GenBank database, we identified a 5,224-bp extra-element in the chromosome of S. agalactiae UCN70. This element was composed of four open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1). One of the ORFs, with a length of 1,479 bp, putatively coded for a 492-amino-acid (ca. 56-kDa) protein that displayed homology with ABC proteins and was a candidate for antimicrobial resistance. By analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence, two Walker A motifs (positions 38 to 46 and 342 to 350), two Walker B motifs (positions 138 to 142 and 443 to 448), two ABC signatures (positions 118 to 123 and 423 to 428), and two H-loop switches (positions 171 and 477) were identified (Fig. 2). Most ABC systems are involved in transport (importers or exporters) and share an organization of two hydrophobic transmembrane domains (TMDs) and two hydrophilic intracytoplasmic domains (13). The latter domains are characterized by the ATP-hydrolyzing domain (also referred to as the nucleotide-binding domain [NBD]), which comprises both Walker A and B motifs and the ABC signature (4, 13). Another category of ABC systems (class 2), those which lack detectable TMDs, is apparently not implicated in transport but rather, at least for some members, in mRNA translation and DNA repair (4). Class 2 also includes several proteins that confer resistance to macrolides and related compounds, such as Msr-like, Vga-like, and Lsa-like proteins (4). Interestingly, the novel ABC system contained no TMDs and showed 23 to 27%, 27 to 28%, and 45 to 53% amino acid identities with the aforementioned proteins, respectively. Like Msr(A) and other class 2 ABC systems (4, 20), the novel protein actually consisted of two NBDs fused into a single protein, explaining the two copies of Walker A and B motifs as well as those of the ABC signature (Fig. 2). Finally, the novel ABC transporter showed a G+C content of 31.8%, which is slightly lower than those of S. agalactiae (35.6%) and other streptococcal genomes (36.8 to 41.8%). The origin of this gene is likely low-G+C Gram-positive bacteria but remains unknown. Based on structural similarity, the novel gene was termed lsa(C) by the Nomenclature Center for MLS Resistance Genes (http://faculty.washington.edu/marilynr/).

FIG. 1.

Schematic map of lsa(C)-containing genetic element identified in the chromosome of S. agalactiae UCN70. ORFs are shown as arrows, with each arrow indicating the orientation of the coding sequence, and target site duplications (ATTAGAA) are indicated with black bars. The orf1, orf2, and orf3 genes putatively code for a site-specific recombinase of the phage integrase family, a replication protein, and a transcriptional regulator from S. agalactiae, respectively. The nucleotide sequence corresponding to the upstream region of the lsa(C) gene is represented in detail. The −35 and −10 promoter boxes are underlined, and the transcription start site is represented by an arrow. The start codon of lsa(C) and its putative ribosome-binding site (RBS) are also indicated. Numbered half-arrows indicate primers used for PCR mapping of the element (see Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Amino acid sequence comparison of Lsa(C) and other related ABC proteins involved in MLS resistance, i.e., Lsa(A), Lsa(B), Msr(A), and Vga(A) (GenBank accession no. AY737525, AJ579365, X52085, and M90056, respectively). The two copies each of the Walker A and B motifs and ABC signatures are boxed, and H-loop switches are also indicated. Similarities in amino acid sequences are marked by asterisks (same amino acid), colons (strong similarity), and dots (family similarity). Multiple-sequence alignment was done with ClustalX 1.83 software.

Drug resistance pattern conferred by the ABC protein Lsa(C).

A 2,079-bp DNA fragment comprising the novel gene and its putative promoter region was amplified with specific primers (Table 1) from the genomic DNA of S. agalactiae UCN70 and inserted into the shuttle vector pAT28. Once expressed in S. agalactiae BM132, it conferred a 64-fold increase in the MICs of lincomycin and clindamycin, a >16-fold increase of the MIC of dalfopristin, and a 256-fold increase of the MIC of tiamulin, whereas no change was observed in the MICs of macrolides and a ketolide (Table 2). The profile of cross-resistance to lincosamides, streptogramins A, and pleuromutilins, which we propose to designate the LSAP phenotype, was similar to that of S. agalactiae UCN70, although the level of resistance to tiamulin was much lower in the parental strain (Table 2). A similar LSAP phenotype has already been reported for staphylococci with Vga(A) and its variant as well as with Vga(C) (7, 10). In Enterococcus faecalis, Lsa(A) is responsible for intrinsic resistance not only to lincosamides and streptogramins A (24) but also to pleuromutilins (our unpublished data). For Staphylococcus sciuri, an LSA phenotype was demonstrated to be related to the expression of the plasmid-mediated lsa(B) gene (11). Although Lsa(A) and other members of the class 2 ABC proteins are presumed to function as efflux pumps, the biochemical basis of resistance remains unclear. Two studies showed decreased accumulations of radiolabeled erythromycin and lincomycin in the presence of Msr(A) and Vga(A)LC, respectively (18, 19). These proteins might recruit a membrane-spanning protein to cause active efflux of antibiotics, but no membrane partners have been identified yet (18, 19). Alternatively, a ribosome-related mechanism of resistance, such as ribosomal protection, could also be hypothesized. The accessibility of the antibiotic to its ribosomal target would be prevented by the ABC protein, reducing the driving force for import. Interestingly, Lsa-like proteins are homologous to the elongation factor eEF-3 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is involved in the translation cycle of fungi (1). Another homologue of eEF-3 has also been identified in E. coli (RbbA, encoded by yhiH) and could be involved in translation by accelerating the release of deacyl-tRNA from the ribosome (28).

TABLE 2.

MICs of macrolides and related compounds against S. agalactiae UCN70 clinical isolate, S. agalactiae BM132 reference strain, and BM132 transformants harboring pAT28 plasmid or lsa(C)-containing pAT28 plasmid

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) for S. agalactiae strain or isolate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCN70 | BM132 | BM132/ pAT28 | BM132/ pAT28Ωlsa(C) | |

| Macrolides | ||||

| Erythromycin | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Azithromycin | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Spiramycin | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Ketolide | ||||

| Telithromycin | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Lincosamides | ||||

| Lincomycin | 2 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 4 |

| Clindamycin | 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2 |

| Streptogramins | ||||

| Quinupristin | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Dalfopristin | 32 | 2 | 2 | >32 |

| Quinupristin-dalfopristin | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Pleuromutilin | ||||

| Tiamulin | 1 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 32 |

Genetic environment of lsa(C).

Comparison of the DNA sequence flanking the 5,224-bp extra-element of S. agalactiae UCN70 with the genome of S. agalactiae 2603V/R (GenBank accession no. AE009948) revealed that the element was inserted into the chromosome. The element was inserted precisely in an intergenic region lying between chromosomal genes encoding a protein belonging to the FstK/SpoIIIE family and a transcriptional regulator of the Cro/CI family. This element was composed of four ORFs (Fig. 1). orf1 putatively coded for a product (379 amino acids) exhibiting 94% identity and 96% similarity to a site-specific recombinase of the phage integrase family from S. agalactiae 18RS21 (GenBank accession no. EAO62075). The orf2-encoded protein (344 amino acids) showed 92% identity and 95% similarity to a replication protein from S. agalactiae 18RS21 (GenBank accession no. EA062073). The product of orf3 (97 amino acids) showed 95% identity and 95% similarity to a transcriptional regulator from S. agalactiae 18RS21 (GenBank accession no. EA061638). The fourth ORF (492 amino acids) corresponded to the lsa(C) gene. Interestingly, since this extra-element was bracketed by a 7-bp duplication of a target site (ATTAGAA), this structure was likely a mobile (or mobilized) genetic element. However, this structure did not resemble a typical transposon (absence of inverted repeats and of a transposase-encoding gene). The putative site-specific recombinase encoded by orf1 might be related to the acquisition event, but this remains to be demonstrated. The promoter sequences for lsa(C) expression were determined using a 5′-RACE system (Fig. 1).

Distribution of lsa(C) among 18 other S. agalactiae isolates.

The lsa(C) gene was detected by PCR in 17 of the 18 tested S. agalactiae isolates collected from New Zealand, with only the nontypeable (genotype C) strain being negative (16). For the 17 lsa(C)-positive isolates, PCR mapping showed that the lsa(C) gene was part of an element that was structurally indistinguishable from (n = 14) or similar to (n = 3) the 5,224-bp extra-element of S. agalactiae UCN70. The absence of amplification of the lsa(C) gene from 50 lincosamide-susceptible isolates of S. agalactiae (data not shown) confirmed that Lsa(C) is not an indigenous ABC protein in this species.

In conclusion, we have identified a novel resistance determinant, lsa(C), responsible for the acquired LSA resistance phenotype in S. agalactiae isolates from New Zealand. We also highlighted the role of this gene in resistance to pleuromutilins, and we proposed that the drug resistance phenotype be named the LSAP phenotype. PCR detection with specific primers may be useful for detection of this unusual resistance phenotype during epidemiological surveys. However, characterization of the biochemical mechanism of resistance needs further investigation. It also remains to be demonstrated if this chromosomal extra-element can be mobilized in vitro.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale et de la Recherche (EA2128), Université Caen Basse-Normandie, France.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, C. B., et al. 2006. Structure of eEF3 and the mechanism of transfer RNA release from the E-site. Nature 443:663-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brzychczy-Wloch, M., et al. 2010. Genetic characterization and diversity of Streptococcus agalactiae isolates with macrolide resistance. J. Med. Microbiol. 59:780-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2009. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; approved standard, 19th ed. M100-S19. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 4.Davidson, A. L., E. Dassa, C. Orelle, and J. Chen. 2008. Structure, function, and evolution of bacterial ATP-binding cassette systems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72:317-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domelier, A. S., et al. 2008. Molecular characterization of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus agalactiae strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1227-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fluegge, K., S. Supper, A. Siedler, and R. Berner. 2004. Antibiotic susceptibility in neonatal invasive isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae in a 2-year nationwide surveillance study in Germany. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4444-4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gentry, D. R., et al. 2008. Genetic characterization of Vga ABC proteins conferring reduced susceptibility to pleuromutilins in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4507-4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gygax, S. E., et al. 2006. Erythromycin and clindamycin resistance in group B streptococcal clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1875-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horodniceanu, T., L. Bougueleret, N. El-Solh, D. H. Bouanchaud, and Y. A. Chabbert. 1979. Conjugative R plasmids in Streptococcus agalactiae (group B). Plasmid 2:197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadlec, K., and S. Schwarz. 2009. Novel ABC transporter gene, vga(C), located on a multiresistance plasmid from a porcine methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3589-3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kehrenberg, C., K. K. Ojo, and S. Schwarz. 2004. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the multiresistance plasmid pSCFS1 from Staphylococcus sciuri. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:936-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko, W. C., et al. 2001. Serotyping and antimicrobial susceptibility of group B Streptococcus over an eight-year period in southern Taiwan. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:334-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kos, V., and R. C. Ford. 2009. The ATP-binding cassette family: a structural perspective. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66:3111-3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsen, J. W., and J. L. Sever. 2008. Group B Streptococcus and pregnancy: a review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 198:440-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leclercq, R. 2002. Mechanisms of resistance to macrolides and lincosamides: nature of the resistance elements and their clinical implications. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:482-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malbruny, B., A. M. Werno, T. P. Anderson, D. R. Murdoch, and R. Leclercq. 2004. A new phenotype of resistance to lincosamide and streptogramin A-type antibiotics in Streptococcus agalactiae in New Zealand. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:1040-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novak, R., and D. M. Shlaes. 2010. The pleuromutilin antibiotics: a new class for human use. Curr. Opin. Invest. Drugs 11:182-191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novotna, G., and J. Janata. 2006. A new evolutionary variant of the streptogramin A resistance protein, Vga(A)LC, from Staphylococcus haemolyticus with shifted substrate specificity towards lincosamides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:4070-4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds, E., J. I. Ross, and J. H. Cove. 2003. Msr(A) and related macrolide/streptogramin resistance determinants: incomplete transporters? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 22:228-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross, J. I., et al. 1990. Inducible erythromycin resistance in staphylococci is encoded by a member of the ATP-binding transport super-gene family. Mol. Microbiol. 4:1207-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schrag, S., R. Gorwitz, K. Fultz-Butts, and A. Schuchat. 2002. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease. Revised guidelines from CDC. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 51:1-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuchat, A. 1998. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease in the United States: shifting paradigms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:497-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sendi, P., L. Johansson, and A. Norrby-Teglund. 2008. Invasive group B streptococcal disease in non-pregnant adults: a review with emphasis on skin and soft-tissue infections. Infection 36:100-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh, K. V., G. M. Weinstock, and B. E. Murray. 2002. An Enterococcus faecalis ABC homologue (Lsa) is required for the resistance of this species to clindamycin and quinupristin-dalfopristin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1845-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trieu-Cuot, P., C. Carlier, C. Poyart-Salmeron, and P. Courvalin. 1990. A pair of mobilizable shuttle vectors conferring resistance to spectinomycin for molecular cloning in Escherichia coli and in gram-positive bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werno, A. M., T. P. Anderson, and D. R. Murdoch. 2003. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of group B streptococci in New Zealand. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2710-2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu, J. J., et al. 1997. High incidence of erythromycin-resistant streptococci in Taiwan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:844-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu, J., et al. 2006. Molecular localization of a ribosome-dependent ATPase on Escherichia coli ribosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:1158-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]