Abstract

We assessed the roles of baseline gag and gag-pol cleavage site mutations (CSM) on the virological outcome of a darunavir-based regimen in highly antiretroviral-experienced patients. We showed the association, in multivariate analysis, between the A431V gag CSM and the virological response, defined as a reduction in plasma HIV-1 RNA to <50 copies/ml at month 3 (P = 0.028). Our results suggest that a specific gag CSM might have a role on protease inhibitor susceptibility in an inhibitor-specific manner.

HIV resistance to protease inhibitors (PI) results from the selection and accumulation of mutations in protease. However, other genomic regions, regions other than protease, might be involved in PI resistance, especially the protease gag and gag-pol cleavage sites (CS). Several studies have shown that gag CS mutations (CSM) might influence the virological outcome of a PI-based regimen (1, 3, 4, 6, 10, 13, 18, 26). The gag-pol frameshift signal is composed of a slippery sequence (U UUU UUA) and a downstream secondary RNA hairpin structure, allowing the ribosome to pause and leading to a Gag/Gag-Pol production ratio of between 1:10 and 1:20 (8, 12, 25). The aim of this study was to assess the role of baseline substitutions in the C-terminal region of the Gag protein on the virological outcome of treatment-experienced patients receiving darunavir (DRV) in a salvage regimen. The baseline substitutions in the C-terminal regions of Gag and Gag-Pol protein CS p7/p1-transframe protein (p7/p1-TFP) and p1-TFP/p6gag-p6pol were studied. Moreover, we analyzed the RNA folding and stability of the baseline gag-pol frameshift signal by measuring the hairpin free energy.

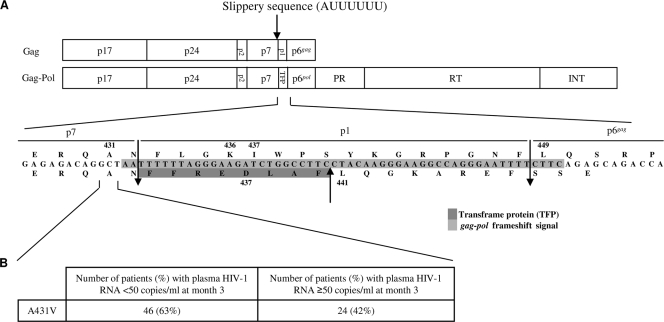

This study included 153 PI-experienced patients, already described in a previous study (5). All had received an antiretroviral-containing regimen that included DRV boosted with ritonavir in association with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and/or nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and/or enfuvirtide. The median baseline HIV-1 RNA value was 4.7 log10 copies/ml (interquartile range [IQR] of 4.3 to 5.2). The median baseline CD4 cell count was 142 cells/mm3 (IQR of 28 to 264). The patients previously received a median of 4 PI (IQR of 3 to 5) before initiating a DRV-based regimen. The virological response, defined as a reduction in plasma HIV-1 RNA to <50 copies/ml at month 3 (M3), occurred in 55% of patients. In this study, we focused on 130 patients, whose baseline plasma specimens were still available to perform a genotyping assay. Fifty-seven (44%) patients displayed virological failure, and 73 (56%) displayed a virological response at M3. After viral RNA extraction, a Gag-protease region of 323 bp, including the CS p7/p1 and p1/p6gag in the gag open reading frame and the CS p7/TFP and TFP/p6pol in the gag-pol open reading frame were amplified and sequenced as already described (16). We focused on specific substitutions documented in the literature: 431, 436, 437, 441, and 449 residues in the gag and gag-pol open reading frames (1, 4, 7, 11, 13, 16, 18, 21, 23, 24, 26, 29) (Fig. 1 A). Differences in the frequency of baseline amino acids in the sequence compared to those in the HXB2 reference strain for these positions and the presence of insertions or deletions in this region were studied according to the virological response at M3 using Fisher exact tests. To estimate whether the mutations, with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis, were an independent predictor of the virological outcome, we used a multivariate logistic regression model that included the following variables: baseline HIV-1 RNA viral load, baseline CD4 cell count, baseline International AIDS Society (IAS) major PI mutations, as well as enfuvirtide coadministration with DRV-ritonavir. RNA hairpin gag-pol frameshift region folding and stability have been determined using Turner's rules, which measure free energy (RNAsoft CombFold [http://www.rnasoft.ca/cgi-bin/RNAsoft/CombFold/combfold.pl]), and were compared between patients considered responders and nonresponders, using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

FIG. 1.

(A) Gag and Gag-Pol precursors with amino acid sequences of the Gag C-terminal region. INT, integrase; PR, protease; RT, reverse transcriptase; TFP, transframe protein. (B) Number and percentage of patients with the baseline A431V gag cleavage site mutation compared to the HXB2 reference sequence in the gag open reading frame according to the virological response at month 3.

gag sequences were successfully obtained for all plasma samples. The following variables were associated with the virological response at M3 using univariate analysis: baseline HIV-1 RNA viral load, baseline CD4 cell count, number of baseline IAS major PI mutations, and coprescription of enfuvirtide (Table 1). Among these variables, three variables remained independently associated with the virological response at M3 in the multivariate analysis: DRV score, baseline HIV-1 RNA viral load, and coprescription of enfuvirtide. No association between the occurrence of virological failure at M3 and baseline gag and gag-pol CSM has been shown. Similarly, no association between deletions or insertions in the baseline sequences and virological outcome has been evidenced.

TABLE 1.

Factors associated with virological response as assessed by univariate and multivariate regression logistic analyses

| Factora |

P valueb by: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |

| DRV score for 14R, 20I, 34Q, 47V, 50V, 54M, 55R, 74P, 76V, and 84V | <0.0001 | |

| Baseline HIV-1 RNA (log10 copies/ml) | <0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| Baseline CD4 cell count (no. of cells/mm3) | 0.015 | 0.294 |

| Baseline IAS major PI mutations (≤4 vs >4) | 0.009 | 0.279 |

| Baseline coprescription of T20 in T20-naïve patients | 0.029 | 0.007 |

| No. of active drugs/GSS | 0.143 | |

| HIV-1 subtype B vs not subtype B | 0.300 | |

| A431V (p7/p1 Gag cleavage site) | 0.036 | 0.027 |

DRV, darunavir; GSS, genotypic susceptibility score; IAS, International AIDS Society; PI, protease inhibitor; T20, enfuvirtide.

The P values by Fisher's exact test for univariate analysis and the P values by multivariate logistic regression analysis are shown. The significant values in the multivariate analysis are shown in boldface type.

The baseline A431V gag CSM (p7/p1) was present in 46 of the 73 patients (63%) who had a plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load below 50 copies/ml at M3 and in 24 of the 57 (42%) patients with HIV-1 RNA who had a viral load above 50 copies/ml at M3 (Fig. 1B). Baseline A431V gag CSM was associated with a virological response as assessed by univariate analysis (P = 0.036). This substitution remained independently associated with virological response (P = 0.028) in multivariate analysis (Table 1). No association was found between the baseline hairpin free energy and the occurrence of virological failure at M3.

The roles of CSM in p7/p1-TFP and p1-TFP/p6gag-p6pol have been well evaluated in vitro. Their presence has been associated with an increase of Gag processing (4, 7, 9, 18, 21, 23), allowing, in some cases, a partial recovery of the viral replicative capacity (4, 18, 23, 26, 29, 30). These substitutions may enhance the affinity of the CS amino acids for protease, either by increasing Van der Waals forces (9, 14, 18) and/or hydrogen bonds (18) or by improving contacts with the protease active site (4, 27). The presence of gag CSM alone (2, 23, 24) or associated with PI mutations (4, 18) may impact on the level of PI phenotypic resistance (20, 22, 23). Mutations in the gag-pol frameshift may contribute to enhanced PI resistance by raising frameshift efficiency, either by increasing slippage (8, 13) or stability of the gag-pol frameshift hairpin (2, 13).

In vivo, several gag and gag-pol CSM were found to be associated with specific PI resistance mutations (1, 3, 10, 13, 14, 16, 18, 19, 30). The prevalence of CSM increases with the number of major PI resistance mutations (23, 30) in treatment-experienced patients compared to antiretroviral-naïve patients (10, 11, 20, 28).

In our study, the presence of the A431V CSM at baseline was significantly and independently associated with a better virological response at M3 in multivariate analysis. This has never been reported for PI-experienced patients. However, we recently reported in antiretroviral-naïve patients receiving a dual-boosted PI regimen (fosamprenavir or atazanavir both associated with saquinavir) as a first-line regimen without any PI mutations in the protease-coding region a positive impact on the virological outcome of the presence, at baseline, of the D437 substitution in the gag-pol open reading frame (17).

In previous studies, the A431V mutation has been associated with virological failure (28), with an increase in Gag precursor cleavage (7, 9, 21), a rise in the viral replicative capacity (20, 26), and also an increase in the phenotypic resistance of almost all the PI tested (4, 23, 24). Furthermore, a study assessing recombinant viruses that harbor the A431V substitution, added to different PI major mutations by site-directed mutagenesis, reported a decrease or increase in the replicative capacity, as well as fluctuations in the level of PI susceptibility (increased or reduced) according to the PI tested (15). Moreover, in another study conducted in highly experienced patients, baseline gag CSM, including A431V, were not associated with virological outcome (23). However, DRV, the last marketed PI, was not tested in any of these latter studies.

Currently, in patients receiving a DRV-containing regimen, only one study has shown an association between the presence of baseline A431V gag CSM and the selection in the protease coding region of the L76V mutation associated with resistance to DRV and lopinavir (16). In our study, the prevalence of the L76V mutation at baseline was too low to enable assessment of such an association. Moreover, genotypic data were not available at the time of failure.

This is the first study to show the positive impact of a gag CSM on the virological outcome of a DRV-containing regimen in highly antiretroviral-experienced patients. DRV displays a potent antiviral activity and has an original chemical structure leading to a specific binding profile with the protease active site which might explain the activity that it maintains on mutant viruses and its genotypic resistance profile. Thus, we could hypothesize that interactions between the enzyme and substrate might impact the nature and position of gag CSM involved in DRV susceptibility. In the literature, A431V has been reported as associated with virological outcome. In contrast to previous studies, our study was carried out in highly antiretroviral-experienced patients that harbor viruses with a median number of 4 major PI resistance mutations and who previously received a median number of 4 PI before initiating the DRV-based regimen (5). Thus, it is difficult to distinguish between whether the A431V mutation had been selected by the previous PI-based regimens or was present in archived PI-resistant variants not detected by bulk sequencing before any PI-based regimen. Further site-directed mutagenesis experiments assessing recombinant viruses harboring the A431V substitution in the presence or absence of DRV resistance-associated mutations would be of interest in order to evaluate the role of this mutation on the virological response. Our results have raised the hypothesis that a specific gag CSM might not have the same impact on virological outcome, according to the PI used as well as the presence or absence of PI-resistance mutations, and could have a direct impact on PI susceptibility in an inhibitor-specific manner.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA et les Hépatites Virales (ANRS), the European AIDS Treatment Network (NEAT, WP6) (grant 037570), and the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under the project “Collaborative HIV and Anti-HIV Drug Resistance Network (CHAIN, WP1, WP2)” (grant 223131).

We have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bally, F., R. Martinez, S. Peters, P. Sudre, and A. Telenti. 2000. Polymorphism of HIV type 1 gag p7/p1 and p1/p6 cleavage sites: clinical significance and implications for resistance to protease inhibitors. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 16:1209-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callebaut, C. S., et al. 2007. In vitro HIV-1 resistance selection to GS-8374, a novel phosphonate protease inhibitor: comparison with lopinavir, atazanavir and darunavir, abstr. 16. XVI Int. HIV Drug Resist. Workshop, Barbados.

- 3.Côté, H. C., Z. L. Brumme, and P. R. Harrigan. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease cleavage site mutations associated with protease inhibitor cross-resistance selected by indinavir, ritonavir, and/or saquinavir. J. Virol. 75:589-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dam, E., et al. 2009. Gag mutations strongly contribute to HIV-1 resistance to protease inhibitors in highly drug-experienced patients besides compensating for fitness loss. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Descamps, D., et al. 2009. Mutations associated with virological response to darunavir/ritonavir in HIV-1-infected protease inhibitor-experienced patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:585-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dierynck, I., et al. 2007. Impact of gag cleavage site mutations on the virological response to darunavir/ritonavir in treatment-experienced patients in POWER 1, 2 and 3, abstr. 21. XVI Int. HIV Drug Resist. Workshop, Barbados.

- 7.Doyon, L., et al. 1996. Second locus involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to protease inhibitors. J. Virol. 70:3763-3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doyon, L., C. Payant, L. Brakier-Gingras, and D. Lamarre. 1998. Novel Gag-Pol frameshift site in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants resistant to protease inhibitors. J. Virol. 72:6146-6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fehér, A., et al. 2002. Effect of sequence polymorphism and drug resistance on two HIV-1 Gag processing sites. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:4114-4120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallego, O., C. de Mendoza, A. Corral, and V. Soriano. 2003. Changes in the human immunodeficiency virus p7-p1-p6 gag gene in drug-naive and pretreated patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1245-1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Diaz, A., et al. 2008. Treatment-emergent gag cleavage site mutations during virological failure of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors, abstr. 73. XVII Int. HIV Drug Resist. Workshop, Sitges, Spain.

- 12.Karacostas, V., E. J. Wolffe, K. Nagashima, M. A. Gonda, and B. Moss. 1993. Overexpression of the HIV-1 gag-pol polyprotein results in intracellular activation of HIV-1 protease and inhibition of assembly and budding of virus-like particles. Virology 193:661-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knops, E., et al. 2009. Differences in the frameshift-regulating p1-site in treatment-naive and PI-resistant HIV isolates, abstr. 99. XVIII Int. HIV Drug Resist. Workshop, Fort Myers, FL.

- 14.Kolli, M., S. Lastere, and C. A. Schiffer. 2006. Co-evolution of nelfinavir-resistant HIV-1 protease and the p1-p6 substrate. Virology 347:405-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolli, M., E. Stawiski, C. Chappey, and C. A. Schiffer. 2009. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease-correlated cleavage site mutations enhance inhibitor resistance. J. Virol. 83:11027-11042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert-Niclot, S., et al. 2008. Impact of gag mutations on selection of darunavir resistance mutations in HIV-1 protease. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:905-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larrouy, L., et al. 2010. gag mutations can impact virological response to dual-boosted protease inhibitor combinations in antiretroviral-naïve HIV-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2910-2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maguire, M. F., et al. 2002. Changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag at positions L449 and P453 are linked to I50V protease mutants in vivo and cause reduction of sensitivity to amprenavir and improved viral fitness in vitro. J. Virol. 76:7398-7406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malet, I., et al. 2007. Association of Gag cleavage sites to protease mutations and to virological response in HIV-1 treated patients. J. Infect. 54:367-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mammano, F., C. Petit, and F. Clavel. 1998. Resistance-associated loss of viral fitness in human immunodeficiency virus type 1: phenotypic analysis of protease and gag coevolution in protease inhibitor-treated patients. J. Virol. 72:7632-7637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mammano, F., V. Trouplin, V. Zennou, and F. Clavel. 2000. Retracing the evolutionary pathways of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to protease inhibitors: virus fitness in the absence and in the presence of drug. J. Virol. 74:8524-8531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nijhuis, M., et al. 2007. Changes in HIV Gag and protease cannot explain persistent viraemia in the majority of patients failing first-line lopinavir/ritonavir therapy, abstr. 133. XVI Int. HIV Drug Resist. Workshop, Barbados.

- 23.Nijhuis, M., et al. 2007. A novel substrate-based HIV-1 protease inhibitor drug resistance mechanism. PLoS Med. 4:e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parkin, N., C. Chappey, E. Lam, and C. Petropoulos. 2005. Reduced susceptibility to protease inhibitors (PI) in the absence of primary PI resistance-associated mutations, abstr. 108. XIV Int. HIV Drug Resist. Workshop, Québec City, Québec, Canada.

- 25.Parkin, N. T., M. Chamorro, and H. E. Varmus. 1992. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag-pol frameshifting is dependent on downstream mRNA secondary structure: demonstration by expression in vivo. J. Virol. 66:5147-5151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parry, C. M., et al. 2009. Gag determinants of fitness and drug susceptibility in protease inhibitor-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 83:9094-9101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prabu-Jeyabalan, M., E. A. Nalivaika, N. M. King, and C. A. Schiffer. 2004. Structural basis for coevolution of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid-p1 cleavage site with a V82A drug-resistant mutation in viral protease. J. Virol. 78:12446-12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verheyen, J., et al. 2008. Relevance of HIV gag cleavage site mutations in failures of protease inhibitor therapies, abstr. 48. XVII Int. HIV Drug Resist. Workshop, Sitges, Spain.

- 29.Zennou, V., F. Mammano, S. Paulous, D. Mathez, and F. Clavel. 1998. Loss of viral fitness associated with multiple Gag and Gag-Pol processing defects in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants selected for resistance to protease inhibitors in vivo. J. Virol. 72:3300-3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang, Y. M., et al. 1997. Drug resistance during indinavir therapy is caused by mutations in the protease gene and in its Gag substrate cleavage sites. J. Virol. 71:6662-6670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]