Abstract

Kill kinetics and MICs of finafloxacin and ciprofloxacin against 34 strains with defined resistance mechanisms grown in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB) at pH values of 7.2 and 5.8 and in synthetic urine at pH 5.8 were determined. In general, finafloxacin gained activity at low pH values in CAMHB and remained almost unchanged in artificial urine. Ciprofloxacin MICs increased and bactericidal activity decreased strain dependently in acidic CAMHB and particularly in artificial urine.

Bacteria colonizing or infecting a host grow under hostile conditions, sense changing environmental stress via diverse quorum sensing, and other two-component systems, and respond by up- or downregulating the expression levels of appropriate proteins, which in turn can affect the susceptibility of the cell to antibiotics (2, 11). Examples of environmental stress include, e.g., growth at extreme temperatures, pH, osmotic pressure, and depletion of nutrients, etc.; Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus causing uncomplicated cystitis or growing in urine or in biofilms on indwelling urethral catheters are such examples (3, 8, 24, 28, 31, 34, 35, 38).

Thus, it is physiologically relevant and clinically important to study the antibacterial activities of agents under test conditions which mimic the infectious focus most closely. Therefore, we used cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB), pH 7.2 and pH 5.8 (Oxoid GmbH, Wesel, Germany), and synthetic urine, pH 5.8, containing 11 solutes each, in concentrations found in a 24-h period in the urine of healthy men (14) for the comparison of the bacteriostatic and -cidal activities of finafloxacin (batch CBC000288) and ciprofloxacin (batch CBC000290).

(Part of the data presented in this paper were shown as a poster at the 48th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Washington, DC, October 2008.)

Thirty-four phenotyped and/or genotyped strains were used for the examination of MICs and kill kinetics, according to CLSI guidelines (6, 7, 19). S. aureus ATCC 29213, E. coli ATCC 25922, and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, as well as moxifloxacin as an external standard, served as controls. Tests were run in duplicate; the higher values were reported in case of deviation (1.2%). Kill kinetics were examined by using finafloxacin and ciprofloxacin at bioequivalent concentrations of 16×, 4×, and 1× the individual MIC values, as measured in the corresponding media. Samples for determination of viable counts were taken at 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h. Drug carryover was minimized first by dilution and second by plating the aliquots on cation-enriched agar, thus inactivating the fluoroquinolones. In order to quantify the reduction of viable counts and the speed of kill, the times needed to reduce the inocula by 3-log10 titers and kill rates were calculated as described recently (32). Furthermore, kill rates were normalized to a drug exposure of 1 mg/liter, as the drug concentration/isolate/media and pH associations vary considerably under the different growth conditions studied.

A comparison of MIC values of finafloxacin generated in CAMHB at either pH 7.2 or pH 5.8 reveals that the MICs of finafloxacin decreased in CAMHB at the lower pH by 1 to 3 dilution steps for almost all of the indicator strains tested, except for E. coli ATCC 25922 and the E. coli wild-type (WT) strain (no change in MICs). The decrease in MICs was independent of both the fluoroquinolone susceptibility and species of strains tested (Table 1 ).

TABLE 1.

Antibacterial activities of finafloxacin and ciprofloxacin

| Strain (resistance mechanism)b | MIC (μg/ml) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finafloxacin |

Ciprofloxacin |

|||||

| CAMHB |

Synthetic urine, pH 5.8 | CAMHB |

Synthetic urine, pH 5.8 | |||

| pH 7.2 | pH 5.8 | pH 7.2 | pH 5.8 | |||

| S. aureus | ||||||

| ATCC 29213 (MSSA)a | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 | 8 |

| ATCC 12600 (MSSA) | 0.25 | 0.015 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 8 |

| 133 (WT) | 0.25/0.125 | 0.015 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 8 |

| clone 16 (grlA[S80P]) | 0.25 | 0.03 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 64 |

| 105-11 (grlA[S80F] gyrA[S84A]) | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 128 |

| 104-13 (grlA[S80F] gyrA[S84L]) | 2 | 1 | 8 | 16 | 32 | >128 |

| 103-17 (grlA[S80F] grlA[E84V] gyrA[S84L]) | 8 | 4 | 32 | 64 | 128 | >128 |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus ATCC 15305a | 0.25 | 0.015 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 8 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae ATCC 13813 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 8 |

| E. faecalis | ||||||

| ATCC 19433a | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

| ATCC 29212 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| E. coli | ||||||

| ATCC 25922a | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.5 |

| ATCC 11775 | 0.25 | 0.015 | 0.125 | 1 | 0.06 | 2 |

| WT | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.06 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 |

| WT-2 (gyrA[D87Y])a | 1 | 0.06/0.125 | 1 | 0.125 | 2 | 16 |

| WT-3-M4 (gyrA[S83L] gyrA[D87G] parC[S80I]) | 128 | 16 | 128 | 32 | >128 | >128 |

| WT-3-1-M4 (gyrA[S83L] gyrA[D87G] parC[S80R]) | 32 | 4 | 32 | 2 | 32 | >128 |

| WT-3-M21 (gyrA[S83L] gyrA[D87G], lacks parC, marR deletion at 80 bp) | 64 | 8 | 64 | 8 | 64 | >128 |

| WT-4-M2-1 (lacks gyrA, parC[S80I])a | 0.25 | 0.015 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2 |

| MI (gyrA[S83L]) | 4 | 0.5 | 8/4 | 0.5/0.25 | 4 | 64 |

| MI-4 (gyrA[S83L] parC[S80I])a | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0.5 | 8/4 | 128 |

| MII (gyrA[S83L], lacks parC, marR deletion at 175 bp) | 16 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 32 | >128 |

| MIII (gyrA[S83L] gyrA[D87G], parC [S80I], marR deletion at 74 bp) | >128 | 64 | >128 | 128 | >128 | >128 |

| ESBL-producing CIA TEM-7 | 0.5 | 0.015/0.03 | 64 | 0.06 | 4 | >128 |

| ESBL-producing 85 (Ur 4731/06) | 64 | 8 | 64 | 64 | 64 | >128 |

| K. pneumoniae | ||||||

| ATCC 13883 | 0.6 | 0.015 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 1 | 2 |

| ESBL-producing ATCC 700603 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0.25 | 4 | 32 |

| ESBL-producing 20 SHV-27 TEM | 32/16 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 64 | >128 |

| ESBL-producing Klebsiella oxytoca 23 SHV-12 TEM-1 | 128 | 16 | 128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| C. freundii ATCC 8090 | 0.015 | ≤0.0075 | 0.06 | ≤0.0075 | ≤0.0075 | ≤0.0075 |

| Proteus mirabilis ATCC 9240a | 0.5 | 0.25/0.125 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.015 | 0.06 | 2 |

| Enterobacter cloacae ATCC 13047 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 |

| S. marcescens ATCC 13880 | 2 | 0.5/0.25 | 0.06/0.125 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 2 |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 10145a | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 4 |

Time-kill experiments were performed with these strains.

MSSA, methicillin-susceptible S. aureus.

Finafloxacin MICs were higher in synthetic urine than in acidic CAMHB but identical to those determined in CAMHB at a pH value of 7.2 (exceptions include most Gram-positives, three E. coli strains, and Citrobacter freundii). E. coli ATCC 11775, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 10145, and Serratia marcescens ATCC 13880 were more susceptible in synthetic urine than they were in CAMHB, pH 7.2 (Table 1). In contrast, ciprofloxacin generally lost activity in acidic CAMHB and particularly did so in artificial urine (Table 1).

An extraordinary increase in the MICs of both finafloxacin and ciprofloxacin at the acidic pH in synthetic urine (from 0.5 and 0.06 to 64 and 128 μg/ml, respectively) was recorded for the extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing clinical isolate E. coli CIA TEM 7. The reasons for this phenomenon are unknown, as this isolate has not yet been characterized genetically.

The bactericidal activities of bioequivalent concentrations (i.e., multiples of the MICs, as determined in the two media) of finafloxacin and ciprofloxacin were compared with each other in CAMHB, pH 7.2, and in synthetic urine, pH 5.8. The absolute drug concentrations used under these conditions for finafloxacin were almost the same, as the MICs differed in the two media by one titration step, if at all (except for P. aeruginosa), whereas the ciprofloxacin concentrations were twice as high (E. coli ATCC 25922) to up to 128 times higher (E. coli WT-2) in synthetic urine than in CAMHB, pH 7.2.

In general, the bactericidal activities of both of the fluoroquinolones are comparable under these prevailing conditions, as evidenced by the times needed to reduce the inocula of the test strains by 3-log10 titers (Table 2 ).

TABLE 2.

Kill rates and times needed for reduction of viable counts by 3-log10 titers calculated for the log-linear phases of time-kill curves

| Strain | Kill rate (h−1)/time (h) needed for 3-log10 kill |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finafloxacin |

Ciprofloxacin |

|||||||||||

| CAMHB, pH 7.2 |

Synthetic urine, pH 5.8 |

CAMHB, pH 7.2 |

Synthetic urine, pH 5.8 |

|||||||||

| 1× MIC | 4× MIC | 16× MIC | 1× MIC | 4× MIC | 16× MIC | 1× MIC | 4× MIC | 16× MIC | 1× MIC | 4× MIC | 16× MIC | |

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 | 1.2/5.6 | 1.9/3.7 | 1.7/3.9 | 0.5/12.8 | 1.6/4.3 | 1.4/4.9 | 1.1/6.3 | 1.5/4.6 | 1.4/4.9 | 1.1/6.3 | 0.9/7.7 | 1.0/6.9 |

| S. saprophyticus ATCC 15305 | 0.2/27.6 | 1.2/5.7 | 1.5/4.6 | 0.4/17.2 | 1.2/5.7 | 1.3/5.3 | ||||||

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 1.1/6.3 | 3.2/2.1 | 6.3/1.1 | 1.3/5.3 | 2.3/3.0 | 5.6/1.2 | 1.9/3.6 | 1.9/3.6 | 1.8/3.8 | 1.1/6.3 | 2.9/2.4 | 6.6/1.0 |

| E. coli WT-2 | 1.0/6.9 | 1.2/5.7 | 1.8/3.8 | 0.06/>24 | 1.4/4.9 | 1.9/3.6 | 0.7/9.8 | 1.9/3.6 | 2.4/2.8 | 0.3/23 | 2.5/2.7 | 3.1/2.2 |

| E. coli WT-4-M2-1 | 1.5/4.6 | 2.9/2.4 | 4.5/1.5 | 2.0/3.4 | 3.1/2.2 | 3.1/2.2 | ||||||

| E. coli MI-4 | 1.8/3.8 | 2.3/3.0 | 2.4/2.8 | 1.7/4.0 | 2.7/2.6 | 2.8/2.5 | ||||||

| P. mirabilis ATCC 9240 | 0.6/11.5 | 3.6/1.9 | 6.2/1.1 | 1.5/4.6 | 2.8/2.5 | 5.0/1.4 | ||||||

| E. cloacae ATCC 13047 | 0.8/8.6 | 1.6/4.3 | 2.3/3.0 | 1.0/6.9 | 2.0/3.4 | 2.2/3.1 | ||||||

| E. faecalis ATCC 29212 | 0.9/7.7 | 1.4/4.9 | 1.5/4.6 | 0.2/>24 | 1.2/5.7 | 1.3/5.3 | 1.0/6.9 | 1.3/5.3 | 1.2/5.7 | 0.6/11.5 | 1.2/5.7 | 1.4/4.9 |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 10145 | 1.9/3.6 | 2.6/2.6 | 3.3/2.1 | 1.3/5.3 | 1.8/3.8 | 2.2/3.1 | ||||||

The kill rates calculated for finafloxacin against the two staphylococci tested are almost concentration independent in both media (Table 2). In contrast, the kill rates for finafloxacin against all E. coli and the remaining reference strains tested were concentration dependent in both media (Table 2). Similar kill rates were calculated for most of the strains (except E. coli ATCC 25922) exposed to ciprofloxacin (Table 2).

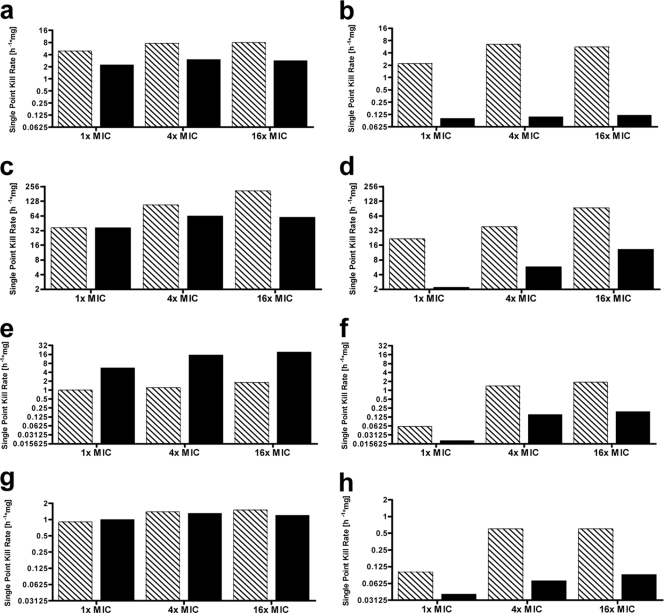

These data demonstrate that the absolute kill rates for both of the fluoroquinolones are almost comparable. However, the absolute finafloxacin or ciprofloxacin concentrations to which the strains studied in this series of experiments were exposed differed by up to 32-fold, so the values were concentration normalized in order to enable a direct comparison of the two agents. A comparison of the normalized kill rates reveals that the values of finafloxacin are higher, i.e., more rapid killing occurs, than those of ciprofloxacin for S. aureus ATCC 29213 and E. coli ATCC 25922, lower for E. coli WT-2, and comparable for E. faecalis ATCC 29212 when the strains were grown in CAMHB at pH 7.2. The normalized kill rates of finafloxacin are up to 47 times higher than those of ciprofloxacin for all four strains grown in synthetic urine at pH 5.8 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Relative single-point kill rates normalized to a drug concentration of 1 mg/liter. Relative single-point kill rates of finafloxacin (hatched bars) and ciprofloxacin (filled bars) in CAMHB, pH 7.2 (left), and synthetic urine, pH 5.8 (right), against S. aureus ATCC 29213 (a and b), E. coli ATCC 25922 (c and d), E. coli WT-2 (e and f), and E. faecalis ATCC 29212 (g and h).

The data generated in this series of experiments confirm, in agreement with previous findings (reviewed in references 10 and 36), that the MICs and bactericidal activity of ciprofloxacin are reduced in acidic media and in synthetic urine. Higher urinary concentrations of magnesium, which are commonly in the range of 8 to 10 mM, account in large part for this reduction in activity. Supplementation of standard media with magnesium at levels present in human urine results in 2- to 16-fold increases in the MICs of any commercially available fluoroquinolone for various bacterial species. The reduced potencies of the fluoroquinolones in urine can also be ascribed in part to the diminished activities of many fluoroquinolones at low pH levels prevailing in these media. Decreased bacteriostatic or bactericidal activities in acidified media could be demonstrated for every commercially available fluoroquinolone. Finafloxacin, however, is almost not affected by growth in urine and is even activated by growth in an acidic standard medium.

Other drug classes like aminoglycosides, macrolides, and tetracyclines and trimethoprim are also affected by these phenomena (1, 15, 20, 21, 26, 27, 29, 33, 37) and are characterized by an increased propensity for resistance development (9). In general, acidity—provided the molecules are not hydrolyzed—has little effect on the bacteriostatic activity of β-lactams (4, 18, 30), but their bactericidal activity is significantly diminished to an almost bacteriostatic effect (13). Furthermore, the β-lactamase inhibitory activities of tazobactam and sulbactam, but not clavulanate, are variably reduced at low pH values, with 50% inhibitory concentrations being up to 300-fold higher at pH 6.5 than at pH 8.0 (18).

These examples demonstrate that the bacteriostatic and/or bactericidal activities of many agents used in the treatment of bacterial infections are impaired at the low pH values and/or high osmolarity which prevail at many infectious sites (5, 9, 12, 16, 17, 22, 23, 25).

The in vitro activity of finafloxacin, however, is not negatively affected by these conditions, thus indicating that finafloxacin may be effective in the treatment of infections within acidic foci. Controlled clinical studies to address this hypothesis are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research grant from MerLion Pharmaceuticals GmbH, Berlin, Germany.

This publication is dedicated to Harald Labischinski, who died on 24 August 2010. His work was devoted to the discovery and development of new antibacterials. Finafloxacin was the last project on which he worked.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aagaard, J., P. O. Madsen, P. Rhodes, and T. Gasser. 1991. MICs of ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim for Escherichia coli: influence of pH, inoculum size and various body fluids. Infection 19(Suppl. 3):167-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson, S., and P. Williams. 2009. Quorum sensing and social networking in the microbial world. J. R. Soc. Interface 6:959-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beenken, K. E., et al. 2004. Global gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 186:4665-4684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodey, G. P., V. Rodriguez, and S. Weaver. 1976. Pirbenicillin, a new semisynthetic penicillin with broad-spectrum activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 9:668-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borrill, Z., C. Starkey, J. Vesttbo, and D. Singh. 2005. Reproducibility of exhaled breath condensate pH in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. Respir. J. 25:269-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute/NCCLS. 1999. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents, vol. 19, p. 18. Approved guideline M26-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute/NCCLS. 2001. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, vol. 21, p. 1. 11th informational supplement. M100-S11. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotter, P. D., and C. Hill. 2003. Surviving the acid test: response of Gram-positive bacteria to low pH. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:429-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalhoff, A., S. Schubert, and U. Ullmann. 2005. Effect of pH on the in vitro activity of and propensity for emergence of resistance to fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and a ketolide. Infection 33(Suppl. 2):36-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eliopoulos, G. M., and C. T. Eliopoulos. 1993. Activity in vitro of the quinolones. In D. C. Hooper and J. S. Wolfson (ed.), Quinolone antibacterial agents, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 11.Geske, G. D., J. O'Neill, and H. E. Blackwell. 2008. Expanding dialogues: from natural autoinducers to non-natural analogues that modulate quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37:1432-1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gitlin, N. 1990. Ascitic fluid acidosis in bacterial peritonitis: a poor prognostic sign? Hepatology 11:896-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodell, E. W., R. Lopez, and A. Tomasz. 1976. Suppression of lytic effect of beta-lactams on Escherichia coli and other bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 73:3293-3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffith, D. P., D. M. Musher, and C. Itin. 1976. The primary cause of infection-induced urinary stones. Invest. Urol. 13:346-350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gudmundsson, A., H. Erlendsdottir, M. Gottfredsson, and S. Gudmundsson. 1991. Impact of pH and cationic supplementation on in vitro postantibiotic effect. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:2617-2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt, J. F., et al. 2000. Endogenous airway acidification. Implications for asthma pathophysiology. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 161:694-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalantzi, L., et al. 2006. Characterisation of the human upper gastrointestinal content under conditions simulating bioavailability/bioequivalence studies. Pharm. Res. 23:165-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livermore, D. M., and J. E. Corkill. 1992. Effects of CO2 and pH on inhibition of TEM-1 and other β-lactamases by penicillanic acid solutions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:1870-1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorian, V. (ed.). 1996. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine, 4th ed. Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, MD.

- 20.Miller, T., and S. Phillips. 1983. Effect of physiological manipulation on the chemotherapy of experimentally induced renal infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 23:422-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minuth, J. N., D. M. Musher, and S. B. Thorsteinsson. 1976. Inhibition of the antibacterial activity of gentamicin by urine. J. Infect. Dis. 133:14-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montuschi, P. 2007. Analysis of exhaled breath condensate in respiratory medicine: methodological aspects and potential clinical applications. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 1:5-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ojoo, J. C., S. A. Mulrennan, J. A. Kastelik, A. H. Morice, and A. E. Redington. 2005. Exhaled breath condensate pH and exhaled nitric oxide in allergic asthma and in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 60:22-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Neill, E. O., et al. 2008. Novel Staphylococcus aureus biofilm phenotype mediated by the fibronectin-binding proteins, FnBPA and FnBPB. J. Bacteriol. 190:3835-3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandit, N. K. 2007. Introduction to the pharmaceutical sciences. Chapter 9: drug absorption. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 26.Papapetropoulou, M., J. Papavassiliou, and N. J. Legakis. 1983. Effect of the pH and osmolarity of urine on the antibacterial activity of gentamicin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 12:571-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peddie, B. A., and S. T. Chambers. 1993. Effects of betaines and urine on the antibacterial activity of aminoglycosides. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 31:481-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Resch, A., R. Rosenstein, C. Nerz, and F. Götz. 2005. Differential gene expression profiling Staphylococcus aureus cultivated under biofilm and planktonic conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2663-2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabath, L. D. 1978. Six factors that increase the activity of antibiotics in vivo. Infection 6(Suppl. 1):67-71. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders, C. C. 1983. Alzocillin: a new broad spectrum penicillin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 11(Suppl. B):21-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato, S., and H. Kobayashi. 2003. Bacterial responses to alkaline stress. Sci. Prog. 66:271-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schaper, K. J., S. Schubert, and A. Dalhoff. 2005. Kinetics and quantification of anti bacterial effects of beta-lactams, macrolides, and quinolones against gram-positive and gram-negative RTI pathogens. Infection 33(Suppl. 2):3-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlessinger, D. 1988. Failure of aminoglycoside antibiotics to kill anaerobic, low-pH, and resistant cultures. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1:54-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schumann, W. 2007. Bacterial stress sensors. In S. K. Calderwood (ed.), Protein reviews: cell stress proteins, vol. 7. Springer Science and Business Media LLC, New York, NY.

- 35.Stickler, D. J., N. S. Morris, J. C. Robert, R. J. C. McLean, and C. Fuqua. 1998. Biofilms on indwelling urethral catheters produce quorum-sensing molecules in situ and in vitro. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3486-3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thauvin-Eliopoulos, C., and G. M. Eliopoulos. 2003. Activity in vitro of the quinolones. In D. C. Hooper and J. S. Wolfson (ed.), Quinolone antibacterial agents, 3rd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 37.Wisell, K. T., G. Kahlmeter, and C. G. Giskes. 2008. Trimethoprim and enterococci in urinary tract infections: new perspectives on an old issue. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:35-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yarwood, J. M., D. J. Bartels, E. M. Volper, and E. P. Greenberg. 2004. Quorum sensing in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 186:1838-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]