Abstract

Bacterial resistance to β-lactam antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, etc.) is commonly the result of the production of β-lactamases. The emergence of β-lactamases capable of turning over carbapenem antibiotics is of great concern, since these are often considered the last resort antibiotics in the treatment of life-threatening infections. β-Lactamases of the GES family are extended-spectrum enzymes that include members that have acquired carbapenemase activity through a single amino acid substitution at position 170. We investigated inhibition of the GES-1, -2, and -5 β-lactamases by the clinically important β-lactamase inhibitor clavulanic acid. While GES-1 and -5 are susceptible to inhibition by clavulanic acid, GES-2 shows the greatest susceptibility. This is the only variant to possess the canonical asparagine at position 170. The enzyme with asparagine, as opposed to glycine (GES-1) or serine (GES-5), then leads to a higher affinity for clavulanic acid (Ki = 5 μM), a higher rate constant for inhibition, and a lower partition ratio (r ≈ 20). Asparagine at position 170 also results in the formation of stable complexes, such as a cross-linked species and a hydrated aldehyde. In contrast, serine at position 170 leads to formation of a long-lived trans-enamine species. These studies provide new insight into the importance of the residue at position 170 in determining the susceptibility of GES enzymes to clavulanic acid.

Gram-negative bacteria are responsible for more than 30% of all hospital-acquired infections and up to 70% of infections within intensive care units (14, 18). β-Lactam antibiotics, including penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems, are commonly used in the treatment of these infections (30). This class of antibiotics function as mechanism-based inhibitors of cell wall biosynthesis by forming an irreversible, covalent adduct with penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), the enzymes responsible for cross-linking the cell wall (12). When unable to maintain the integrity of their cell wall, the bacteria are either unable to reproduce (a bacteriostatic effect) and/or survive (a bactericidal effect) (12). Gram-negative bacteria use multiple mechanisms to become resistant to these antibiotics, including decreased permeability of the outer cell membrane to antibiotics, mutation of PBPs to decrease their affinity for the antibiotic, and/or expression of β-lactamases, enzymes which degrade the antibiotic (41). β-Lactamases are the means most commonly used by Gram-negative bacteria in achieving resistance.

β-Lactamases are classified as belonging to one of four molecular classes (A to D) based on their amino acid sequence (12). Members of class A, C, and D possess an active-site serine residue which catalyzes hydrolysis of the β-lactam bond. Members of class B are metalloenzymes that hydrolyze the β-lactam bond using an active-site zinc ion. Most clinical isolates resistant to β-lactam antibiotics harbor enzymes belonging to class A. These enzymes were initially narrow spectrum, capable of hydrolyzing penicillins and early generation cephalosporins, but selective pressure has resulted in the appearance of hundreds of mutants with the ability to hydrolyze β-lactam antibiotics of every known class (4, 26).

Clavulanic acid, tazobactam, and sulbactam are β-lactamase inhibitors developed to extend the utility of β-lactam antibiotics for which resistance has previously been developed (11). These inhibitors function as mechanism-based inactivators of β-lactamases. When coadministered with a β-lactam antibiotic, β-lactamase inhibitors inactivate the β-lactamase, thus preventing the antibiotic from being hydrolyzed by the enzyme. Examples of such combinations in clinical use include amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, and ticarcillin-clavulanic acid.

Carbapenem antibiotics are often considered the last-resort β-lactams due to their broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, including both Gram-positive and -negative pathogens, and their high potency (19). Furthermore, unlike with penicillins and cephalosporins, clinical use of carbapenems has not resulted in the selection of carbapenem-resistant variants within the most abundant types of class A β-lactamases, such as TEM, CTX, and SHV (11). Instead, new class A β-lactamases, the carbapenemases, have appeared which are able to produce resistance to carbapenems alone or in conjunction with other resistance mechanisms. These enzymes are classified into six families (GES, KPC, IMI/NMC, SME, BIC, and SFC), which share 32 to 70% amino acid sequence identity (15, 39). Most of these enzymes are rare in clinical isolates, but members of the GES and KPC families are commonly found and now pose a serious threat to our ability to treat life-threatening infections (38).

The GES family of class A β-lactamases are found in 4 of the 10 most common pathogens causing hospital-acquired infections (18). The first variant described, GES-1, was found in Klebsiella pneumoniae in 1998 and classified as an extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) (27). Since that time, 14 additional variants have been identified (GES-2 to -15) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia marcescens, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae, and Acinetobacter baumannii from clinical isolates originating in France, Portugal, Spain, Brazil, Argentina, Netherlands, South Africa, Japan, Korea, Greece, China, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Poland (http://www.lahey.org/studies/other.asp#table1). GES-3, -7 to -9, -11, and -13 are also classified as ESBLs, but GES-2, -4, -5, and -6 have gained the ability to hydrolyze carbapenems (20, 22, 40).

Carbapenemase activity by GES enzymes is attributed to a single amino acid substitution at position 170 (Ambler numbering used) (13). The canonical residue at this position in most class A β-lactamases is an asparagine; however, exceptions are known. For example, glycine can be found in certain Streptomyces species, serine can be found in some Bacteroides and Streptomyces species, and histidine can be found in VEB-1, PER-type β-lactamases, and various Bacteroides species (1, 28). GES-1 has a glycine at position 170 and shows negligible carbapenemase activity (27). GES-2 and -5 contain a single amino acid substitution to an asparagine and serine, respectively, which confers carbapenemase activity (2, 29, 37) and makes them clinically significant. Biochemical characterization of GES-1, -2, and -5 has also revealed that they show some susceptibility to β-lactamase inhibitors, with GES-1 and -2 having 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of 5 and 1 μM, respectively (27, 29). In order to further investigate the importance of this residue in inhibition by the clinically used inhibitor clavulanic acid, we performed kinetic inhibition studies, UV difference (UVD) spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry (MS) of GES-clavulanic acid complexes of the GES-1, -2, and -5 β-lactamases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

A constitutive expression vector, pHF016, containing the gene for the GES-1 (pHF:GES-1), GES-2 (pHF:GES-2), or GES-5 (pHF:GES-5) β-lactamases, cloned between the unique NdeI and HindIII sites, was used for MIC determinations as previously described (13). For protein expression, pET24a(+) containing the gene for GES-1 (pET:GES-1), GES-2 (pET:GES-2), or GES-5 (pET:GES-5), cloned between the unique NdeI and HindIII sites, was used as previously described (13).

MIC determinations.

The MICs of β-lactam antibiotics were determined by the broth microdilution method as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (9). GES-1, -2, or -5 was expressed in E. coli JM83 using the plasmid pHF:GES-1, -2, or -5, respectively. E. coli JM83 harboring pHF016 was used as a control. The MICs were determined in Mueller-Hinton II broth (Difco) using a bacterial inoculum of 5 × 105 CFU/ml. All plates were incubated at 37°C for 16 to 20 h before the results were interpreted.

Expression and purification of GES enzymes.

To express GES-1, E. coli BL21(DE3) was transformed with pET:GES-1, and cells containing the construct were selected on LB agar supplemented with 60 μg of kanamycin/ml. Selected cells were grown in LB medium supplemented with 60 μg of kanamycin/ml at 37°C and 220 rpm until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.4. IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the cells were further grown at 25°C and 220 rpm for 24 h. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 20,000 × g and 4°C, and the medium was concentrated by centrifugal filtration at 3,000 × g and 4°C using a Centricon Plus 70 (Millipore) concentrator with a 10-kDa molecular mass cutoff filter. The concentrated medium was then dialyzed against buffer A (20 mM Tris [pH 7.5]) and fractionated on a DEAE (Bio-Rad) column (2.5 by 22 cm) using a linear gradient of NaCl (0 to 0.3 M) in buffer A. The fractions containing GES-1 were pooled and dialyzed against 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.6) and stored at 4°C. The enzyme concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using a BCA (bicinchoninic acid) protein assay kit (Pierce), using bovine serum albumin as a standard. SDS-PAGE showed the enzyme purity to be >95%. GES-2 and -5 were expressed and purified in the same manner, using the plasmids pET:GES-2 and pET:GES-5, respectively.

Data collection and analysis.

All UV/Vis spectrophotometric data were collected on a Cary 50 spectrophotometer (Varian) at 22°C. Analyses were performed using the nonlinear regression program Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) with data obtained from experiments performed at least in triplicate.

Determination of dissociation constants.

The inhibitor dissociation constant (Ki) for clavulanic acid with GES-1, -2, and -5 was determined using nitrocefin (Δɛ500 = +15,900 cm−1 M−1) as a reporter substrate. Reactions containing 50 mM NaPi (pH 7.0), 100 mM NaCl, 200 and 300 μM (GES-1 and -5) or 10 and 20 μM (GES-2) nitrocefin, and various concentrations of the inhibitor were initiated by the addition of the enzyme (10 nM final for GES-1, 20 nM final for GES-2, and 760 pM final for GES-5). The absorbance was monitored at 500 nm, and the steady-state velocities were determined from the linear phase of the reaction time courses. The initial steady-state velocity data were plotted as a function of inhibitor concentration and the dissociation constant determined by using the method of Dixon (10).

Determination of the rate constant for inhibitor inactivation.

The rate constant describing inactivation by clavulanic acid (kclav) with GES-1, -2, and -5 was determined using nitrocefin as a reporter substrate. This rate constant is different from kinact, which is often reported in the literature, because it represents formation of both transiently and irreversibly inhibited species and not only irreversible inactivation. Reactions containing 50 mM NaPi (pH 7.0), 100 mM NaCl, nitrocefin (100 μM for GES-1, 20 μM for GES-2, and 400 μM for GES-5), and various concentrations of the inhibitor were initiated by the addition of the enzyme (10 nM final for GES-1, 20 nM final for GES-2, and 760 pM final for GES-5). The absorbance was monitored at 500 nm, and the time courses were fit with equation 1.

|

(1) |

where At is the absorbance at time t, A0 is the initial absorbance, vss is the steady-state velocity, vi is the initial velocity, and kinter is the rate constant for the interconversion between vi and vss. The values for kinter were plotted as a function of inhibitor concentration and fit with equation 2.

|

(2) |

where kinter is as described above, kclav is the rate constant describing inactivation, I is the concentration of inhibitor, and KI is the apparent concentration of inhibitor required to reach kinter = kclav/2.

Determination of the partition ratio.

The partition ratio, r or kcat/kinact, was determined by using the titration method (34). Various molar ratios of inhibitor and enzyme (100 nM), up to 1,500:1, were incubated overnight at 4°C in 50 mM NaPi (pH 7.0) and 100 mM NaCl. The remaining activity was measured after a 1:100-fold dilution of the enzyme (1 nM final) into 50 mM NaPi (pH 7.0) and 100 mM NaCl containing excess nitrocefin (600 μM final). The absorbance was monitored at 500 nm, and the steady-state velocities were determined from the linear phase of the reaction time courses. The inhibitor/enzyme ratio resulting in ≥90% inactivation was designated as the partition ratio, as previously defined (6, 24).

Detection and kinetic characterization of enamine species by UV spectroscopy.

The cis- and trans-enamine reaction intermediates, formed during inhibition by β-lactamase inhibitors, are characterized by chromophores absorbing at wavelengths greater than 250 nm (3, 8, 32, 35). Reactions containing 50 mM NaPi (pH 7), 100 mM NaCl, and 500 μM clavulanic acid were initiated by the addition of 5 μM GES-1, -2, or -5. The absorbance from 200 to 350 nm was monitored every 0.1 min over 30 min. Subtracting the spectrum of the enzyme alone from the enzyme-clavulanic acid spectra generated the desired difference spectra.

In order to compare the initial formation of the trans-enamine, we used a SFA-20 stopped-flow apparatus (Hi-Tech Scientific, Salisbury, United Kingdom). Reaction mixtures contained 50 mM NaPi (pH 7.0), 100 mM NaCl, 500 μM clavulanic acid, and 5 μM GES-1, -2, or -5. The trans-enamine species was detected at 264 nm. All time courses were normalized to an absorbance of zero at t = 0 s.

Detection of GES-clavulanic acid reaction intermediates by electrospray-ionization (ESI) MS.

Reactions containing 50 mM NaPi (pH 7.0), 100 mM NaCl, and 70 μM GES-1, -2, or -5 were preincubated in the presence or absence of 1 mM clavulanic acid. A 15-μl aliquot of each reaction was diluted 1:4 into 0.5% formic acid in H2O prior to liquid chromatography-MS (LC-MS) analysis. A 25-μl aliquot of the quenched reaction, containing 12.5 μg of enzyme, was injected onto a Poroshell C3 column (2.1 by 75 mm; Agilent) at 440 μl/min using a Dionex RSLC high-pressure liquid chromatography system (A = H2O with 0.1% formic acid, B = acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid). The gradient was held at 15% B for 4.1 min, followed by a linear gradient from 15 to 90% B over 5.4 min. The gradient was held constant at 90% B for 3 min and then re-equilibrated in 15% B for 6.5 min. The sample was diverted from the MS source during the first 4 min postinjection.

LC-MS was performed on a Bruker MicroQTOF QqTOF instrument. Single MS spectra from 300 to 3,000 m/z were acquired at a spectral sum rate of 1 Hz. Two spectra were averaged together per displayed/saved spectrum. Calibration was provided externally through infused Agilent ESI-low tune mix from m/z 322.0481 to 2,721.8948. A six-point parameterized fit (MicroTOFControl) was used. Instrument parameters were: positive mode with a bias of 4,500 V on the capillary, a -500-V end plate offset, 3.5 Bar of nebulizer gas, dry gas at 8 liters/min and dry gas temperature of 180°C.

The charge/mass deconvolution was performed using Bayesian reconstruction (ABSciex) from exported ASCII data (FlexAnalysis). The following mass reconstruction parameters were used: mass considered was 20,000 to 35,000 Da; signal-to-noise ratio, 5:1, step size, 0.1 Da; and number of iterations, 20. To confirm the findings, the data were also charge deconvolved within FlexAnalysis. Mass agreement with charge deconvolution was identical (data not shown). The average mass error for the GES-1, -2, and -5 measurements was 0.008% (predicted mass averages were 29,216.9, 29,273.9, and 29,246.9 Da for the GES-1, -2, and -5 polypeptides, respectively).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

MICs of β-lactam-clavulanic acid combinations against E. coli JM83 producing GES β-lactamases.

Previous studies have shown that in the presence of clavulanic acid, the MICs of amoxicillin and/or ticarcillin are reduced in strains expressing GES enzymes (27, 29, 37). We evaluated the MIC values for β-lactam-inhibitor combinations used in clinical practice, i.e., amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, against E. coli JM83 expressing GES-1, -2, and -5. We used our constitutive expression vector, which allowed direct comparison of the three enzymes under an identical promoter (Table 1). The MICs for amoxicillin against strains expressing the GES variants are all ≥2048, but the MICs are each reduced in the presence of clavulanic acid. GES-2 is the most susceptible to inhibition by clavulanic acid, with the MIC value for amoxicillin-clavulanic acid approaching background levels. The MICs for ticarcillin also decrease in the presence of clavulanic acid. Strains expressing GES-1 and -5 show 32- and 16-fold reductions, respectively, in the MIC for ticarcillin, whereas GES-2 expression results in a 256-fold decrease in MIC. The identity of the amino acid at position 170 in GES-1, -2, and -5 influences their resistance to inhibition by clavulanic acid, with the canonical asparagine resulting in the highest susceptibility.

TABLE 1.

MICs of β-lactam for E. coli JM83 producing various GES enzymes

| Antimicrobial | MIC (μg/ml) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controla | GES-1 | GES-2 | GES-5 | |

| Amoxicillin | 4 | >2,048 | 2,048 | >2,048 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acidb | 4 | 32 | 8 | 64 |

| Ticarcillin | 4 | 1,024 | 2,048 | 512 |

| Ticarcillin-clavulanic acidc | 2 | 32 | 8 | 32 |

Parental E. coli JM83 strain harboring the vector pHF016 containing no β-lactamase gene.

Clavulanic acid is used at a ratio of 1:2 with the β-lactam.

Clavulanic acid fixed at 2 μg/ml.

Kinetic characterization of clavulanic acid inhibition of GES enzymes.

The IC50 values for clavulanic acid with GES-1 and -2 were previously shown to be in the low micromolar range (27, 29). We evaluated the true dissociation constants (Ki) for clavulanic acid from GES-1, -2, and -5 (Table 2). The affinity of clavulanic acid for GES-1 and -5 is lower than for GES-2. This increased affinity of the GES-2 β-lactamase for clavulanic acid may, in part, account for the increased susceptibility of GES-2 to inhibition. Compared to other class A β-lactamases, the Ki for GES-2 (5.0 μM) is 4- and 12-fold higher than those for the TEM-1 (1.4 μM) and SHV-1 (0.43 μM) β-lactamases, respectively (16, 36). Compared to other carbapenemases, the Ki for GES-2 is comparable to that for NMC-A (3.2 μM) and 3- and 26-fold higher than the Ki values for KPC-2 (1.5 μM) and SME-1 (0.19 μM), respectively (21, 31, 43). Unlike typical class A β-lactamases, GES-1 and -5 do not contain the canonical Asn at position 170, which functions in anchoring the deacylation water molecule in the active site. This residue is also known to be important in substrate binding as reflected in the lower Km values for penicillin and cephalosporin substrates for GES-2 (2, 27, 29). The lower Ki value for clavulanic acid with GES-2 implies that this residue is important in the binding of β-lactamase inhibitors as well.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters for inhibition of GES enzymes by clavulanic acid

| Enzyme | Mean ± SD |

Partition ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (μM) | kclav (s−1) | ||

| GES-1 | 49 ± 4 | 0.023 ± 0.001 | ∼300 |

| GES-2 | 5.0 ± 0.8 | 0.082 ± 0.005 | ∼20 |

| GES-5 | 39 ± 2 | 0.015 ± 0.001 | ∼450 |

In order to evaluate the efficacy of inhibition of GES enzymes by clavulanic acid, we monitored the loss of enzyme activity over time using a continuous assay. This method measures the loss of enzyme activity due to formation of both transiently and irreversibly inactive species. We have defined the rate constant describing this inactivation as kclav. This is different from the kinetic parameter kinact, often reported in the literature, which represents the formation of only irreversibly inactivated species (34) and is determined by a discontinuous method. We chose to use kclav in comparing the ability of clavulanic acid to inhibit GES enzymes, since it is more physiologically relevant. The value for kclav for GES-1 (0.018 s−1) and GES-5 (0.015 s−1) is 4-fold lower than for GES-2 (0.082 s−1) (Table 2). Despite this difference, the half-life for inactivation would still be less than 1 min for all of the enzymes. This enhanced rate constant with GES-2 also would contribute to the increased susceptibility to clavulanic acid, in addition to the increased affinity. The only other class A β-lactamase for which we are aware this parameter has been measured is the carbapenemase KPC-2 (0.027 s−1), which has a value for kclav more similar to GES-1 and -5 than GES-2 (25). Not surprisingly, like GES-1 and -5, KPC-2 is also clinically resistant to amoxicillin in the presence of clavulanic acid (42).

The partition ratio (r) is defined as the number of molecules of inhibitor hydrolyzed by the enzyme prior to irreversible inactivation and is represented by the ratio kcat/kinact (34). The better an enzyme is at evading irreversible inactivation, by hydrolyzing the β-lactam bond of the inhibitor and rendering it inactive, the higher the value of the partition ratio. The partition ratio for GES-2 (r = 20) is at least 10-fold lower than for GES-1 (r = 300) and GES-5 (r = 450) (Table 2). Other non-carbapenemase class A β-lactamases, such as TEM-1 (r = 120) and SHV-1 (r = 40), also have relatively low partition ratios for clavulanic acid (7, 17). Carbapenemases typically have higher partition ratios for clavulanic acid, with NMC-A and KPC-2 having values of 428 and 2,500, respectively (21, 25). GES-5 has the highest carbapenemase activity and GES-1 has the lowest, of the three GES variants studied, but have similar partition ratios. This implies that carbapenemase activity may not always occur in conjunction with higher partition ratios for clavulanic acid.

Low values for the partition ratio result from both the β-lactamase inhibitor being a poor substrate for the enzyme (i.e., low kcat) or an increased ability of the inhibitor to irreversibly inactivate the enzyme (i.e., high kinact). Previous studies have shown that having an Asn at position 170 in GES enzymes leads to a lower turnover of penicillins and cephalosporins (2, 27, 29). Therefore, it is likely that the decreased partition ratio for clavulanic acid with GES-2 is due to decreases in the value for kcat.

Detection of enamine intermediates by UV/Vis spectroscopy.

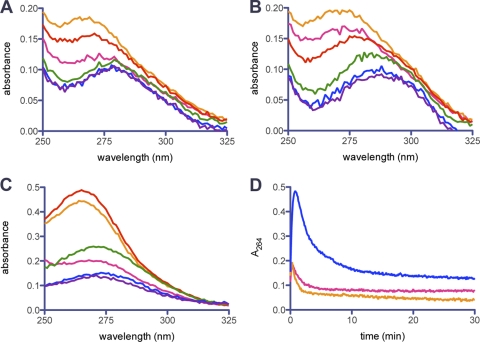

Inhibition of class A enzymes by β-lactamase inhibitors proceeds through a variety of species, both transient and irreversible (Fig. 1). The importance of transient species during inhibition has been well established (11). Since both the cis-enamine (compound 4) and trans-enamine (compound 5) species contain a chromophore (8, 23, 32), we studied the UVD spectra of GES β-lactamases in the presence clavulanic acid to evaluate whether either of these transient species were important during inhibition. When monitored over 30 min, the UVD spectrum for each enzyme revealed a single peak (λmax = 264 nm) that varied in intensity over time, first increasing and then decreasing (Fig. 2). We have assigned this peak to the trans-enamine species (compound 5), since the cis isomer would be predicted to absorb closer to 300 nm. Only minor changes in the spectrum could be detected at 300 nm. We compared the change in absorbance at 264 nm over time in order to compare the relative rate and amount of the trans-enamine formed by each variant (Fig. 2D). The trans-enamine species is formed rapidly in all three enzymes upon addition of clavulanic acid. GES-5 forms 2.5-fold more of the trans-enamine species than GES-1 or -2. The formation and disappearance of the trans-enamine is similar in GES-1 and -2, but this species is longer lived in GES-5. These kinetics are quite different from what is seen in the class A β-lactamase SHV-1 when inhibited by clavulanic acid (35). In this enzyme, formation of the trans-enamine is slow, not reaching a maximum until 15 min. This species was also stable over 60 min, unlike with GES enzymes. In GES-1 and -2, the trans-enamine species would not be the predominant inhibitory complex in vivo, since they rapidly disappear. However, in GES-5 the trans-enamine species survives for at least 10 min. Since this corresponds to approximately half the doubling time of the bacterium, it is reasonable to assume that the trans-enamine species likely contributes to physiologically relevant inhibition of GES-5.

FIG. 1.

Proposed mechanism for the inhibition of GES enzymes by clavulanic acid.

FIG. 2.

UVD spectra of GES-1 (A), GES-2 (B), and GES-5 (C) in the presence of clavulanic acid at time t = 0 min (pink), 0.5 min (orange), 1 min (red), 5 min (green), 20 min (blue), and 30 min (purple). (D) Change in absorbance over time at 264 nm, representing the trans-enamine species, for GES-1 (pink), GES-2 (orange), and GES-5 (blue) in the presence of clavulanic acid.

Since formation of the trans-enamine species was rapid, we used a stopped-flow apparatus to monitor the first 60 s of the reaction in more detail (Fig. 3). There is a small, but reproducible, lag in the time course for all GES enzymes. This would indicate something prior to the formation of the trans-enamine reaction limits the steady-state reaction, such as substrate binding, hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring or tautomerization of the imine to the trans-enamine. The formation of the trans-enamine is fastest with GES-2 and slowest with GES-5. The disappearance of this species is also fastest in GES-2. This would imply that this species is short-lived in GES-2, again consistent with the idea that this is not a physiologically relevant complex during inhibition in vivo.

FIG. 3.

Representative time course at 264 nm for the production of the trans-enamine species with clavulanic acid for GES-1 (solid black line), GES-2 (solid light gray line), and GES-5 (solid dark gray line) as measured by stopped-flow analysis.

Detection of GES-clavulanic acid intermediates by ESI-MS.

In order to detect other species important in the inhibition of GES enzymes by clavulanic acid, we used ESI-MS. The deconvoluted mass spectra reveal that immediately upon mixing, GES-1, -2, and -5 form three major species (Fig. 4). These species are consistent with those previously seen with TEM-2 and SHV-1 (5, 33). Thus, we propose that they represent a cross-linked species between Ser70 and Ser130 (Δ+52, compound 10), either an aldehyde (Δ+70, compound 8) or an irreversibly inactivated complex (Δ+70, compound 11), and a hydrated aldehyde (Δ+88, compound 9). In addition to the main peaks observed, there are also a few minor peaks which we ascribe to hydration products of the main peaks due to their spacing of +Δ18. There is little free enzyme remaining upon mixing of the enzyme with clavulanic acid, which is consistent with rapid inhibition.

FIG. 4.

Deconvoluted mass spectra of GES-1 (A), GES-2 (B), and GES-5 (C) immediately upon mixing (left) and after 20 min (right) with clavulanic acid. The arrow indicates the position of the native enzyme, and all mass changes are relative to this peak.

After 20 min of incubation with clavulanic acid, GES-1 and -5 have begun to regenerate the free enzyme, whereas the GES-2 spectrum has remained essentially unchanged. This implies that the GES-2-clavulanic acid complexes are more stable than those with GES-1 and -5. This is in agreement with the MIC and kinetic data, which show GES-2 to be more susceptible to inhibition by clavulanic acid. In addition, since the GES-2/clavulanic acid complexes 8 to 11 rapidly form and remain stable for over 20 min, these are the species which would be physiologically relevant to inhibition in vivo. This is in contrast to GES-5, where the trans-enamine is more physiologically relevant.

Conclusion.

GES β-lactamases are important targets in the development of novel therapeutic agents. This family of enzymes, through a single amino acid substitution, has expanded its resistance profile to include carbapenem antibiotics. We have investigated the susceptibility of E. coli harboring the GES β-lactamases—GES-1, -2, and -5—to β-lactams in the presence of clavulanic acid. Bacteria producing GES-2, an enzyme containing the canonical Asn at position 170, were more susceptible to β-lactams in the presence of this inhibitor than GES-1 and -5. This is due to both an increased affinity of the enzyme for clavulanic acid and a low partition ratio. Mass spectral data support the idea that the physiologically relevant species in vivo are the cross-linked species, the aldehyde or inactive complex, and the hydrated aldehyde. This is in contrast to GES-5, a carbapenemase possessing a Ser at position 170, in which the trans-enamine is the physiological species. GES-1, which is not a carbapenemase and contains a Gly at position 170 is similar to GES-5 both in its ability to confer resistance to β-lactams in the presence of clavulanic acid and in its kinetics of inhibition. These data provide new insights into the importance of position 170 in determining the susceptibility of GES enzymes to inhibition by clavulanic acid.

Acknowledgments

The MS data are based upon work supported by NSF CHE-0741793.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler, R. P., et al. 1991. A standard numbering scheme for the class A β-lactamases. Biochem. J. 276(Pt. 1):269-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae, I. K., et al. 2007. Genetic and biochemical characterization of GES-5, an extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 58:465-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonomo, R. A., et al. 2001. Inactivation of CMY-2 β-lactamase by tazobactam: initial mass spectroscopic characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1547:196-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, P. A. 2001. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin. Rev. Microbiol. 14:933-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, R. P., R. T. Aplin, and C. J. Schofield. 1996. Inhibition of TEM-2 β-lactamase from Escherichia coli by clavulanic acid: observation of intermediates by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 35:12421-12432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush, K., C. Macalintal, B. A. Rasmussen, V. J. Lee, and Y. Yang. 1993. Kinetic interactions of tazobactam with β-lactamases from all major structural classes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:851-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canica, M. M., et al. 1998. Phenotypic study of resistance of β-lactamase-inhibitor-resistant TEM enzymes which differ by naturally occurring variations and by site-directed substitution at Asp276. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1323-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cartwright, S. J., and A. F. Coulson. 1979. A semi-synthetic penicillinase inactivator. Nature 278:360-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically: approved standard, 7th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 10.Dixon, M. 1953. The determination of enzyme inhibitor constants. Biochem. J. 55:170-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drawz, S. M., and R. A. Bonomo. 2010. Three decades of β-lactamase inhibitors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23:160-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher, J. F., S. O. Meroueh, and S. Mobashery. 2005. Bacterial resistance to β-lactam antibiotics: compelling opportunism, compelling opportunity. Chemical Rev. 105:395-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frase, H., Q. Shi, S. A. Testero, S. Mobashery, and S. B. Vakulenko. 2009. Mechanistic basis for the emergence of catalytic competence against carbapenem antibiotics by the GES family of β-lactamases. J. Biol. Chem. 284:29509-29513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaynes, R., and J. R. Edwards. 2005. Overview of nosocomial infections caused by gram-negative bacilli. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:848-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girlich, D., L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2010. Novel ambler class A carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase from a Pseudomonas fluorescens isolate from the Seine River, Paris, France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:328-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grace, M. E., K. P. Fu, F. J. Gregory, and P. P. Hung. 1987. Interaction of clavulanic acid, sulbactam and cephamycin antibiotics with β-lactamases. Drugs Exp. Clin. Res. 13:145-148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helfand, M. S., et al. 2003. Understanding resistance to β-lactams and β-lactamase inhibitors in the SHV β-lactamase: lessons from the mutagenesis of SER-130. J. Biol. Chem. 278:52724-52729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hidron, A. I., et al. 2008. NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Health Care Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006-2007. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 29:996-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kesado, T., T. Hashizume, and Y. Asahi. 1980. Anti-bacterial activities of a new stabilized thienamycin, N-formimidoyl thienamycin, in comparison with other antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 17:912-917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotsakis, S. D., et al. 2010. GES-13, a β-lactamase variant possessing Lys-104 and Asn-170 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1331-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mariotte-Boyer, S., M. H. Nicolas-Chanoine, and R. Labia. 1996. A kinetic study of NMC-A β-lactamase, an Ambler class A carbapenemase also hydrolyzing cephamycins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 143:29-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moubareck, C., S. Bremont, M. C. Conroy, P. Courvalin, and T. Lambert. 2009. GES-11, a novel integron-associated GES variant in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3579-3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostercamp, D. L. 1970. Vinylogous imides. II. Ultraviolet spectra and the application of Woodward's rules. J. Org. Chem. 35:1632-1641. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padayatti, P. S., et al. 2006. Rational design of a β-lactamase inhibitor achieved via stabilization of the trans-enamine intermediate: 1.28 Å crystal structure of wt SHV-1 complex with a penam sulfone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128:13235-13242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papp-Wallace, K. M., et al. 2010. Inhibitor resistance in the KPC-2 β-lactamase, a preeminent property of this class A β-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:890-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez, F., A. Endimiani, K. M. Hujer, and R. A. Bonomo. 2007. The continuing challenge of ESBLs. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 7:459-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poirel, L., I. Le Thomas, T. Naas, A. Karim, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Biochemical sequence analyses of GES-1, a novel class A extended-spectrum β-lactamase, and the class 1 integron In52 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:622-632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poirel, L., et al. 1999. Molecular and biochemical characterization of VEB-1, a novel class A extended-spectrum β-lactamase encoded by an Escherichia coli integron gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:573-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poirel, L., et al. 2001. GES-2, a class A β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa with increased hydrolysis of imipenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2598-2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poole, K. 2004. Resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61:2200-2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Queenan, A. M., et al. 2000. SME-type carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamases from geographically diverse Serratia marcescens strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3035-3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rizwi, I., A. K. Tan, A. L. Fink, and R. Virden. 1989. Clavulanate inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus β-lactamase. Biochem. J. 258:205-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saves, I., et al. 1995. The asparagine to aspartic acid substitution at position 276 of TEM-35 and TEM-36 is involved in the β-lactamase resistance to clavulanic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 270:18240-18245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverman, R. B. 1988. Mechanism-based enzyme inactivation: chemistry and enzymology. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 35.Sulton, D., et al. 2005. Clavulanic acid inactivation of SHV-1 and the inhibitor-resistant S130G SHV-1 β-lactamase. Insights into the mechanism of inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 280:35528-35536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vakulenko, S., and D. Golemi. 2002. Mutant TEM β-lactamase producing resistance to ceftazidime, ampicillins, and β-lactamase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:646-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vourli, S., et al. 2004. Novel GES/IBC extended-spectrum β-lactamase variants with carbapenemase activity in clinical enterobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 234:209-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh, T. R. 2008. Clinically significant carbapenemases: an update. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 21:367-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walther-Rasmussen, J., and N. Hoiby. 2007. Class A carbapenemases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:470-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weldhagen, G. F. 2006. GES: an emerging family of extended spectrum β-lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Newsletter. 28:145-149. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilke, M. S., A. L. Lovering, and N. C. Strynadka. 2005. β-Lactam antibiotic resistance: a current structural perspective. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:525-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yigit, H., et al. 2001. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1151-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yigit, H., et al. 2003. Carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella oxytoca harboring carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase KPC-2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3881-3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]