Abstract

A microarray study of chemostat growth on insoluble cellulose or soluble cellobiose has provided substantial new information on Clostridium thermocellum gene expression. This is the first comprehensive examination of gene expression in C. thermocellum under defined growth conditions. Expression was detected from 2,846 of 3,189 genes, and regression analysis revealed 348 genes whose changes in expression patterns were growth rate and/or substrate dependent. Successfully modeled genes included those for scaffoldin and cellulosomal enzymes, intracellular metabolic enzymes, transcriptional regulators, sigma factors, signal transducers, transporters, and hypothetical proteins. Unique genes encoding glycolytic pathway and ethanol fermentation enzymes expressed at high levels simultaneously with previously established maximal ethanol production were also identified. Ranking of normalized expression intensities revealed significant changes in transcriptional levels of these genes. The pattern of expression of transcriptional regulators, sigma factors, and signal transducers indicates that response to growth rate is the dominant global mechanism used for control of gene expression in C. thermocellum.

Clostridium thermocellum is an anaerobic, thermophilic, Gram-positive bacterium that uses cellulose as the sole source of carbon and energy (1, 2, 8). There is considerable interest in this organism as a model system and a practical agent for conversion of cellulose to ethanol (8, 21). C. thermocellum and some other cellulolytic microbes recruit the enzymes responsible for cellulose hydrolysis into a large extracellular complex called the cellulosome (2, 9). The cellulosome is organized around scaffoldins, which are proteins composed of multiple cohesin domains that recruit dockerin-containing cellulolytic enzymes into the complex by virtue of specific, high-affinity cohesin-dockerin interactions (25, 26). Extensive studies of C. thermocellum have revealed many cellulosomal constituents (13, 27), and biochemical assays have defined many of their independent reactions (1). In combination, these studies have revealed that more than 60 different proteins may be present in the complex (1, 13, 27, 39).

There is also growing information about the regulation of expression of specific clostridial genes during growth on cellulose and other carbon sources (4, 10, 14, 37). Thus, scaffoldin and cellulase genes have similar transcriptional responses to growth rate and substrate (10, 11, 37), and transcriptional regulators have been associated with some cellulase genes (22). Previously, Stevenson and Weimer conducted a real-time PCR survey of the expression of 17 C. thermocellum genes involved in cellulose hydrolysis, intracellular phosphorylation, and catabolite repression and correlated their expression profiles with the formation of fermentation products (31). Most recently, sigma factor signaling in C. thermocellum was established by an elegant combination of bioinformatics and biochemical approaches (17). Collectively, these studies point to the ability of C. thermocellum to exquisitely control expression of certain known genes in response to growth rate and the presence of insoluble cellulose or soluble compounds such as cellobiose.

We have now completed a microarray study of C. thermocellum in order to examine expression responses of the entire genome. Importantly, the use of the chemostat technique allowed the effects of different growth rates to be analyzed separately from the effects of different substrates. Our analysis of global gene expression revealed a set of 348 genes whose expression behaviors were consistent with a model including both growth rates and substrate type. The most highly expressed genes from this set encode glycoside hydrolases, scaffoldins, and other proteins known to participate in cellulose utilization. A large number of transcriptional regulators, signal transduction proteins (34), and sigma factors (17) were also identified, thus expanding our understanding of potential mechanisms of control for clostridial gene expression and protein translation. The expression data also revealed that certain genes among multiple copies from the glycolytic, ethanol fermentation, and H2 evolution pathways were highly expressed under conditions that led to ethanol production. These results highlight the complexity of the clostridial utilization of cellulose and offer many possible avenues for new understanding of this important process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genome model.

The sequence under GenBank accession no. CP000568.1 was used in this work. Annotations were obtained from the DOE Joint Genome Institute Integrated Microbial Genomes server (http://img.jgi.doe.gov). Some additional annotations were incorporated from recently published work (17).

Chemostat growth.

C. thermocellum ATCC 27405 was grown on Sigmacel 50 microcrystalline cellulose (equivalent to Avicel PH101) and used as an inoculum for chemostat studies (31). Cells were grown at 55°C in chemostat culture with continuous stirring. Modified Dehority medium containing (per liter) 3.0 g of cellobiose or 2.7 to 3.1 g of Sigmacel 20 microcrystalline cellulose (Sigma) was delivered to the reactor as segmented slurry. Chemostats were operated to steady state (minimum turnover of three reactor volumes) prior to sampling. For cellobiose, the following dilution rates (D) were studied (h−1; calculated from the mass flow rate of the collected effluent): 0.025, 0.048, 0.064, 0.129, and 0.158. For cellulose, the following dilution rates were studied (h−1): 0.013, 0.084, 0.105, 0.129, 0.159, and 0.206. D is equivalent to the growth rate of the organism at steady-state operation.

mRNA and cDNA preparations.

Total RNA was isolated from freshly collected cells. cDNA was synthesized from isolated RNA and stored at −80°C prior to use. Total DNA was isolated using a Promega Wizard genomic DNA kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and treated with DNase-free RNase One (Promega) following DNA extraction.

Microarray design and data collection.

Quality control tests were performed on RNA samples to ensure purity and integrity by using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA). Double-stranded cDNA was synthesized using a SuperScript double-stranded cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) with random hexamers following Roche NimbleGen's user's guide (28a). The microarray design included 3,189 coding sequences represented by 15 60-mer probes. There were 8 copies of each probe on the array, arranged in a 1:2 probe configuration with no mismatch. Cy3 labeling and hybridization steps were performed using standard protocols from Roche NimbleGen (Madison, WI). The single-color NimbleGen arrays were scanned with a GenePix 4000B microarray scanner. The data were extracted from scanned images by using NimbleScan software.

Microarray analyses.

Expression values were generated using quantile normalization (3) and the robust multichip average algorithm (15, 16). The call file contained 8 replicate intensities for each probe set. These were log2 transformed and further summarized by taking the means of the log-transformed values. There were 343 genes whose log expression values were <6 in all 11 samples, indicating that they were not expressed. Principal component analysis showed that there were no obvious outliers among the different growth rate and substrate samples, and furthermore, the global expression profiles were affected by growth rate and substrate type. The R/Bioconductor package maSigPro was used to identify genes whose expression was growth rate and/or substrate dependent (7). The regression model was as follows:

|

(1) |

where yijk was the expression level of gene k on growth substrate i at growth rate Gij, b0 and d0 were regression coefficients corresponding to the reference group, specified as cellulose, b1 and d1 were the regression coefficients accounting for the differences between the cellobiose and cellulose groups, and eijk was the random variation from all sources other than those incorporated into the model. The P values of the F statistic of the model specified in the equation were computed for all expressed genes and followed by computation of linear step-up false discovery rates; 351 genes having false discovery rates of <0.1 were retained for variable selection. The variable selection was performed using backward stepping, dropping the model terms with P values of >0.05, and 348 genes with R2 values of >0.6 were retained for clustering analysis. There were no obvious outliers among these genes, and their expression profiles were affected by growth rate (D) and/or substrate (S). The expression profiles were assigned to 5 clusters by using the fuzzy c-means algorithm implemented in the R package Mfuzz (20).

Microarray data accession number.

The extensive microarray data set obtained from this effort is available from the NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession number GSE22426.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chip validation.

Comparison of the microarray and previous real-time PCR results (31) revealed a strong correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.69; P value = 2.2 × 10−16) between the two experimental methods, with only Cthe_0110 (hprK, encoding serine kinase of HPr protein) appearing as an outlier. With this validation, we undertook a genome-wide analysis of expression patterns during chemostat growth. Individual genes had significant correlations between the PCR and microarray experiments when the expression levels were affected by either growth rate or substrate. Figure S1 in the supplemental material shows that the expression behaviors of Cthe_2089, encoding CelS, a highly abundant cellulosomal protein, matched quite well in the two experiments, and similar results were obtained with 15 other genes from the previous real-time PCR study (31). No significant correlations were observed when growth rate and substrate effects compatible with equation 1 were not evident.

Microarray results.

Regression analysis using the R package maSigPro (7) was used to investigate correlated changes in gene expression according to the model defined in equation 1. This model has 4 parameters, is fit to 11 data points representing different substrate and growth rate conditions, and can be visualized as 2 trend lines of gene expression versus growth rate, for cellulose and cellobiose (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The expression behavior of each gene was fit using equation 1, and 348 genes whose expression intensities were affected by changes in the growth rate (D) and substrate (S) were identified. Table S1 in the supplemental material lists all of the genes identified by this analysis.

The expression profiles of these 348 genes were sorted into 5 clusters by using the fuzzy c-means algorithm implemented in the R package Mfuzz (20). The Mfuzz package uses a “fuzzy” clustering approach to compute the strength of the association of each gene with the central behavior of the cluster, referred to as a “fuzzy score.” The fuzzy scores for each gene sum to 1. This allows one to define a set of genes that associate with each cluster with a high probability, while other genes may not have a high score for association with a single cluster but may instead have scores that allow partial placement in more than one cluster. This approach is more flexible and less sensitive to experimental noise than traditional “hard” clustering, where each gene must belong to one and only one cluster.

Table S1 in the supplemental material shows each of the 348 genes assigned to the 5 clusters and their individual fuzzy scores. The median fuzzy score for each cluster was >0.98, and the average fuzzy score was >0.9, indicating strongly correlated behaviors of the genes within each cluster with respect to changes in growth rate and substrate. Thus, each cluster has a core set of genes with very high fuzzy scores (i.e., close to 1) which indicate that their collective expression behavior is strongly correlated with that of other members of the cluster with respect to their changes in growth rate and substrate. Moreover, the lack of significant overlap of genes between the clusters also supports the unique characteristics of the clusters and their embedded genes.

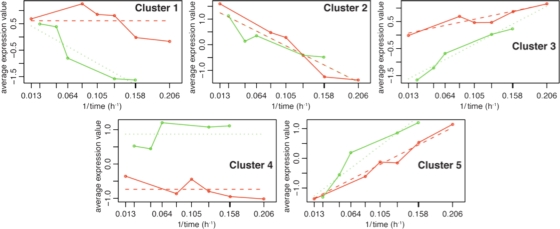

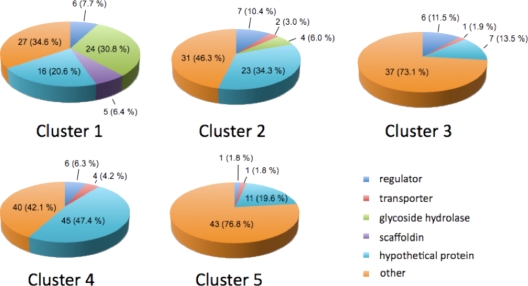

Figure 1 shows that the median profiles of the cluster cores have different substrate- and growth rate-dependent trends, while Fig. 2 summarizes the characteristics of the clustered genes. Many of the clustered genes are associated with growth on cellulose. Other clustered genes encode intracellular proteins such as ribosomal subunits and enzymes, transcriptional regulators, signal transduction proteins, and sigma factors. The clusters also contain many genes encoding hypothetical proteins, establishing a rich new vein for exploration of clostridial cellulose utilization. It is notable that ∼10% of the genes encoding hypothetical proteins also encode a recognizable signal peptide (12), suggesting that they encode proteins which may reasonably be directed toward unknown extracellular aspects of cellulose utilization. Properties of the clusters are described briefly below.

FIG. 1.

Median profiles for genes identified by regression analysis to have substrate- and growth rate-dependent changes in expression intensity. Red, cellulose; green, cellobiose. Cluster 1 contains 78 genes, cluster 2 contains 67 genes, cluster 3 contains 52 genes, cluster 4 contains 95 genes, and cluster 5 contains 56 genes.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of genes clustered by regression analysis according to annotation. The regulator category includes genes with annotations of “regulator,” “signal transduction,” and “*sigma*,” with “*” representing any characters. The scaffoldin annotation includes genes with an annotation of “cellulosome anchoring protein, cohesin region.” The “other” category includes genes not having one of the annotations listed.

Cluster 1.

The median fuzzy score for cluster 1 was 0.999, which is representative of highly correlated behavior. The genes in this cluster exhibited a decrease in expression as the growth rate on cellobiose increased (Fig. 1) and a lesser or no decrease in expression as the growth rate on cellulose increased. Cluster 1 contained 78 genes, including 29 encoding a dockerin domain, 5 encoding scaffoldin proteins, 6 encoding transcriptional regulators and/or signal transduction proteins, and 16 encoding hypothetical proteins (Fig. 2; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). There were 37 genes encoding a signal peptide in this cluster, including 1 encoding a hypothetical protein (Cthe_0399).

Cluster 2.

Cluster 2 was characterized by decreasing expression as the growth rate increased for both cellulose and cellobiose. This cluster contained 67 genes, including 5 encoding dockerin domains (3 glycoside hydrolases and 2 cellulosome enzymes with dockerin type I), 9 encoding transcriptional regulators and/or signal transduction proteins, 2 encoding transporters, and 23 encoding hypothetical proteins (Fig. 2; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). There were 13 genes that encoded a signal peptide, including 4 hypothetical pro- tein genes (the Cthe_1098, Cthe_1099, Cthe_1209, and Cthe_2675).

Cluster 3.

Cluster 3 was characterized by increasing expression as the growth rate increased for both cellulose and cellobiose, with higher expression intensities for cellulose. This cluster contained 52 genes. Annotations suggest that these genes encode primarily ribosomal subunits and cytoplasmic enzymes involved in cofactor, nucleotide, fatty acid, amino acid, and protein synthesis and other enzymes that would reasonably be expected to support an increased growth rate (Fig. 2; see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Cluster 4.

Cluster 4 was characterized by high expression for growth on cellobiose and low expression for growth on cellulose at all growth rates. This cluster contained 95 genes, including 2 encoding dockerin domains (Cthe_0435, encoding a cellulosome enzyme of dockerin type I; and Cthe_0661, encoding ricin B lectin), 8 encoding transcriptional regulators and/or signal transduction proteins, and a surprising 45 genes encoding hypothetical proteins (Fig. 2; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). There were 16 genes encoding a signal peptide, including 6 of the hypothetical protein genes. Other than the large number of genes for hypothetical proteins and transcription factors, cluster 4 genes had annotations, including two-component transcriptional regulators, periplasmic sensor proteins, transporters, and some intracellular enzymes.

Cluster 5.

Cluster 5 genes showed low expression at low growth rates with both cellulose and cellobiose, with expression intensities increasing faster for increased growth rates on cellobiose than for those on cellulose. This cluster contained 56 genes, including 11 encoding hypothetical proteins. Most annotations were for cytoplasmic enzymes (Fig. 2; see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Abundantly expressed genes.

The changes in expression intensity reported here represent the interplay between growth rate and substrate corresponding to equation 1 and other, presently unknown environmental stimuli. Table 1 shows the distribution of genes with expression intensities ranked above the 90th percentile (i.e., top 10% of expression intensities [322 genes]). This ranked list changed primarily in response to growth rate and, to a lesser degree, substrate type (cellulose or cellobiose). Many of the most highly expressed genes (Table 2) encode the most abundant cellulosomal proteins identified by previous laboratory proteomic studies (13, 27, 35, 38). This emphasizes the strong correlation between gene expression levels and accumulation of cellulosomal proteins in C. thermocellum. It also emphasizes the power of regression analysis to successfully model the expression of known cellulose utilization genes.

TABLE 1.

Numbers of clustered genes ranked above the 90th percentile by microarray expression intensity

| Annotation or cluster | Total no. of genes in genome or clusterf | No. of genes ranked above 90th percentile at indicated dilution rate (h−1) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose |

Cellobiose |

|||||||||||

| 0.013 | 0.084 | 0.105 | 0.129 | 0.159 | 0.206 | 0.025 | 0.048 | 0.064 | 0.129 | 0.158 | ||

| Annotation | ||||||||||||

| Regulatora | 94 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 18 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Transporter | 55 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Glycoside hydrolase | 44 | 19 | 15 | 15 | 12 | 5 | 6 | 18 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| Scaffoldinb | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Dockerinc | 73 | 25 | 19 | 20 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 24 | 15 | 11 | 5 | 4 |

| Hypothetical protein | 948 | 46 | 48 | 42 | 59 | 65 | 51 | 55 | 68 | 41 | 45 | 37 |

| Otherd | 2,047 | 233 | 239 | 245 | 235 | 243 | 254 | 218 | 228 | 257 | 261 | 270 |

| Ethanole | 30 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 10 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 15 |

| Cluster | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 78 | 32 | 27 | 27 | 24 | 13 | 12 | 31 | 18 | 10 | 5 | 4 |

| 2 | 67 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 52 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 16 | 18 | 6 | 8 | 11 | 16 | 17 |

| 4 | 95 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| 5 | 56 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 10 |

Genes from the 348 clustered genes having an annotation containing “*regulator*,” “*signal transduction*,” or “*sigma*,” with “*” representing a text wild card of arbitrary length.

Genes from 348 clustered genes having an annotation containing “cellulosome anchoring protein, cohesin region.”

Counts for genes from all clusters having a dockerin module and thus likely part of the cellulosome.

Counts for genes from all clusters not having one of the annotations listed.

Genes associated with ethanol fermentation are also included in “other.”

Since some annotation classes overlap, the sum of annotated genes does not simply add to the number of genes in the genome.

TABLE 2.

Changes in expression intensities of scaffoldinsa and other cluster 1 genes during growth on cellulose or cellobiose

| Gene locus | Protein | Mean intensity | SD | Rank (percentile) | Mean intensity | SD | Rank (percentile) | ΔIntensity (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth on cellulose | D = 0.013 h−1 | D = 0.206 h−1 | ||||||

| Cthe_0271c | 55,001 | 2,233 | 100.0 | 43,214 | 2,825 | 100.0 | −21 | |

| Cthe_2089 | CelS | 44,985 | 2,237 | 99.9 | 35,466 | 1,221 | 99.8 | −21 |

| Cthe_3079 | Orf2p | 39,211 | 2,390 | 99.9 | 27,177 | 2,825 | 98.9 | −31 |

| Cthe_3080 | OlpA | 36,449 | 2,454 | 99.7 | 22,788 | 1,445 | 97.8 | −37 |

| Cthe_3077 | CipA | 34,288 | 1,710 | 99.6 | 22,355 | 1,943 | 97.6 | −35 |

| Cthe_0412 | CelK | 31,217 | 1,534 | 99.3 | 15,967 | 1,055 | 94.6 | −49 |

| Cthe_2972 | XynA | 30,790 | 1,640 | 99.2 | 15,551 | 887 | 94.4 | −49 |

| Cthe_0413 | CbhA | 26,693 | 1,451 | 98.6 | 11,363 | 473 | 90.0 | −57 |

| Cthe_3078 | OlpB | 26,135 | 2,648 | 98.5 | 9,999 | 608 | 87.6 | −62 |

| Cthe_0269 | CelA | 24,353 | 984 | 98.0 | 9,071 | 600 | 86.1 | −63 |

| Cthe_0452 | 18,683 | 1,074 | 95.9 | 8,369 | 469 | 84.8 | −55 | |

| Cthe_1307 | SbdA | 12,318 | 384 | 90.8 | 7,764 | 291 | 83.1 | −37 |

| Cthe_0736 | 5,584 | 299 | 75.4 | 4,299 | 382 | 69.4 | −23 | |

| Cthe_0735 | 2,822 | 134 | 59.6 | 2,983 | 265 | 61.3 | 6 | |

| Cthe_1667d | 15 | 2 | 0.0 | 13 | 1 | 0.0 | −8 | |

| Growth on cellobiose | D = 0.025 h−1 | D = 0.156 h−1 | ||||||

| Cthe_0271c | 50,542 | 2,472 | 100.0 | 40,449 | 2,174 | 100.0 | −20 | |

| Cthe_2089 | CelS | 47,159 | 3,650 | 99.9 | 15,090 | 935 | 93.3 | −68 |

| Cthe_3079 | Orf2p | 38,718 | 2,950 | 99.7 | 13,183 | 1,105 | 91.4 | −66 |

| Cthe_3080 | OplA | 36,885 | 3,672 | 99.6 | 13,014 | 920 | 91.1 | −65 |

| Cthe_3077 | CipA | 36,270 | 2,606 | 99.6 | 12,206 | 499 | 90.0 | −66 |

| Cthe_0412 | CelK | 35,439 | 1,428 | 99.5 | 11,367 | 438 | 88.8 | −68 |

| Cthe_2972 | XynA | 31,474 | 1,783 | 99.3 | 9,214 | 580 | 84.8 | −71 |

| Cthe_0413 | CbhA | 28,514 | 1,843 | 98.9 | 8,415 | 689 | 83.3 | −70 |

| Cthe_3078 | OlpB | 23,786 | 1,170 | 97.9 | 5,341 | 304 | 74.8 | −78 |

| Cthe_0269 | CelA | 20,522 | 1,220 | 96.5 | 5,128 | 266 | 73.6 | −75 |

| Cthe_0452 | 19,357 | 1,619 | 95.8 | 5,121 | 253 | 73.6 | −74 | |

| Cthe_1307 | SbdA | 15,090 | 781 | 93.1 | 2,034 | 153 | 53.2 | −87 |

| Cthe_0736 | 13,089 | 662 | 91.6 | 1,669 | 155 | 49.7 | −87 | |

| Cthe_0735 | 3,256 | 189 | 63.6 | 906 | 61 | 39.1 | −72 | |

| Cthe_1667d | 12 | 1 | 0.0 | 14 | 2 | 0.0 | 10 | |

Scaffoldin genes are indicated in bold.

Obtained from intensities at the maximum and minimum dilution rates for the indicated substrate.

Cthe_0271, encoding a type 3a, cellulose-binding protein, was the most highly expressed gene in all experiments.

Cthe_1667, encoding an ABC-2-type transporter, was the least highly expressed gene.

The changes in ranked expression were most pronounced for the glycoside hydrolase-, scaffoldin-, and dockerin-encoding genes and for regulatory/signal transduction protein genes. Table 2 shows that these genes had large decreases in normalized intensity as the growth rate increased, which primarily accounted for their shift in intensity rankings. At the lowest growth rate studied with cellulose, Cthe_2089 (celS), Cthe_0412 (celK), Cthe_2972 (xynA), Cthe_0413 (cbhA), Cthe_0269 (celA), Cthe_2812 (celT), Cthe_3079 (orf2p), Cthe_3080 (olpA), Cthe_3077 (cipA), and Cthe_3078 (olpB) were ranked above the 97th percentile for expression intensity, while at the highest growth rate with cellulose, only celS, celK, and cipA remained above this metric.

For comparison, at the lowest growth rate on cellobiose, celS, celK, xynA, cbhA, celT, cipA, orf2p, and olpA had expression intensities above the 97th percentile (Table 2). Thus, at low growth rates, there was little discrimination for expression of cellulolytic enzymes and proteins. However, at the highest growth rate with cellobiose, no genes modeled by equation 1 remained above this threshold, representing a progressive shift away from expression of cellulolytic enzymes and proteins.

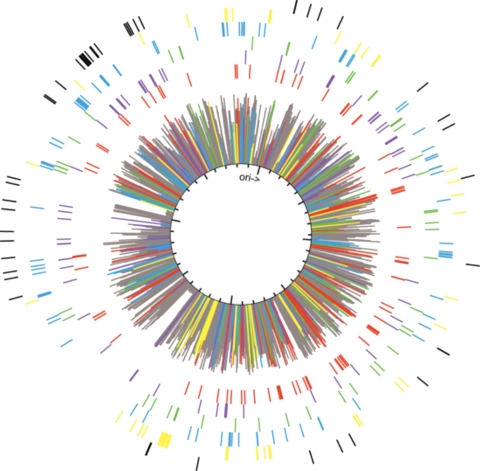

Scope of genomic response.

According to the microarray results, over 10% of the C. thermocellum genome was transcribed differentially during growth on either cellulose or cellobiose. The positions of the expressed genes were distributed throughout the genome (Fig. 3), and among these, only a few multicistronic groups were detected (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Some of these groups included previously identified genes for scaffoldins (Cthe_3077 to Cthe_3080) and sigma factors (17). The present work shows that some glycoside hydrolases (Cthe_0267 to Cthe_0274), putative transporters (Cthe_1383 to Cthe_1386 and Cthe_1761 to Cthe_1765), and nucleotide metabolism enzymes (Cthe_0944 to Cthe_0952) are also coordinately regulated. Other sets of contiguous, coordinately expressed genes encoded hypothetical proteins. It is presently unclear how these genes may be involved directly in cellulose utilization.

FIG. 3.

Genome map of the positions of genes clustered by regression analysis. Red, cluster 1; purple, cluster 2; green, cluster 3; blue, cluster 4; yellow, cluster 5. The outermost circumference of black bars represents genes for which no expression was detected.

Genes encoding scaffoldins.

There are 8 scaffoldin-like genes in C. thermocellum, and the 5 placed into cluster 1 showed differential expression in the chemostat studies (Table 2). The Cthe_3077 (cipA), Cthe_3078 (olpB), Cthe_3079 (orf2p), and Cthe_3080 (olpA) genes were expressed abundantly at low growth rates with both substrates but showed substantial decreases in normalized expression intensity as the growth rate increased. Indeed, only Cthe_3077 remained above the 97th percentile as the growth rate increased, and this was only for growth on cellulose. Cthe_3077 does not encode S-layer homology domains, so the gene product is not directly anchored to the outer cell membrane. However, uniquely among the scaffoldin-like genes, it does encode a cellulose-binding domain. Since a higher growth rate in the chemostat is related to increased substrate availability, C. thermocellum apparently casts the cellulosomal net more widely by expressing Cthe_3077. Among the other scaffoldin genes, Cthe_0452 and Cthe_1307 (sbdA) had expression levels ranked above the 90th percentile at low growth rates, and the corresponding proteins have also been detected by affinity digestion proteomics (13, 27). They were not placed into a microarray cluster because their changes in expression levels were not modeled satisfactorily by equation 1. The different expression patterns for scaffoldin genes show that C. thermocellum exerts precise control over expression of this important family of cellulolytic proteins. Moreover, the expression intensities correlate with prior studies of protein abundance (10, 24, 27). Although the unique contributions of these different configurations of scaffoldins are not clearly understood, they may represent advantageous biological specializations under certain growth conditions.

The other two scaffoldin genes, Cthe_0735 and Cthe_0736, were expressed at relatively low levels, and their intensities decreased as the growth rate was increased. Neither of the encoded proteins has been detected by affinity digestion (13, 27).

Genes encoding dockerin domains.

Of the 73 dockerin-encoding genes present in C. thermocellum, 36 were sorted into clusters according to equation 1. Among these, 21 were ranked above the 90th percentile by expression intensity, and the average percentile rank was 85% (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Changes in their expression intensities arose primarily from changes in growth rate as opposed to changes in substrate (Table 1). Cluster 1 genes included most of the dockerin-encoding genes detected. Genes encoding four enigmatic dockerin proteins (Cthe_0190, Cthe_0661, Cthe_0798, and Cthe_0821) displayed differential expression profiles. Interestingly, the expression of 6 of 18 members of a poorly understood family annotated as “cellulosome enzyme, dockerin type I” was detected, with Cthe_1398 being the only member with a functional annotation, XghA. Except for Cthe_2360, which was ranked above the 92nd percentile for expression intensity and placed into cluster 1 but not detected by proteomics, all dockerin-containing proteins detected by the microarray study were also detected in a switchgrass proteomic study (35).

The 37 dockerin-encoding genes that were not sorted into clusters were also of interest (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). On average, these genes had considerably lower ranked intensities than those of the genes sorted into clusters. Indeed, only 4 genes in this group, Cthe_2179 (pectate lyase/allergen), Cthe_0258 (cellulosome enzyme, dockerin type I), Cthe_0536 (celB), and Cthe_0270 (chiA), were ranked above the 90th percentile by expression intensities. Changes in their expression intensities were not modeled satisfactorily by equation 1. Interestingly, 24 of the dockerin-encoding genes not sorted into clusters were detected in the switchgrass proteomic study as additional contributors to the cellulosome (27). These genes encode enzymes with accessory functions, such as arabinofuranosidases, pectinases, xylanases, lichenase, chitinase, lipolytic enzyme, peptidase, and others. It is likely that growth conditions or inducers required for high-level expression of these genes were not present in chemostat growth on purified cellulose but were present in the switchgrass batch growth experiment. In addition, there were 13 dockerin-containing genes in C. thermocellum that were not detected by either the microarray or proteomic studies. Their average ranked intensity was below the 32nd percentile, thus associating low expression intensity with the negative proteomic results.

Genes encoding transporters.

Oligosaccharide transport is an essential, energy-conserving mechanism in C. thermocellum (37), and a detailed analysis of its importance has been published (23). Although the identities of transporters involved have not yet been established completely (23, 32), the substrate binding preferences of five extracellular sugar binding domains have been defined (24a). From the total of ∼60 C. thermocellum genes annotated to have various transport functions, 8 were identified by regression analysis using equation 1, including Cthe_2118 and Cthe_0819 from cluster 2, Cthe_3148 from cluster 3, Cthe_1762, Cthe_1763, Cthe_1919, and Cthe_2270 from cluster 4, and Cthe_2247 from cluster 5. Cthe_0819 was ranked above the 97th percentile for expression level (Table 2) and is predicted to be an ABC transporter-related protein. Interestingly, the adjacent genes Cthe_0818 and Cthe_0820 are both predicted to be transmembrane proteins by hidden Markov modeling (12), suggesting that this three-gene cluster may be involved in the transport of cellobiose or other oligosaccharides. Cthe_1020 (CbpB), previously identified to be a high-affinity cellodextrin binding protein, was expressed at the 99th percentile during growth on both cellulose and cellobiose at all growth rates.

Genes encoding hypothetical and unknown proteins.

The expression patterns for 102 genes encoding hypothetical proteins were also sorted into clusters. Of these, 12 genes encoding a signal peptide were given further consideration, as they may yield exported proteins (see Table S5 in the supplemental material). BLAST analysis showed that these genes are found primarily in the order Clostridiales. Cthe_0271 was the most highly expressed gene in C. thermocellum during growth on both cellulose and cellobiose, while the well-known gene Cthe_2809 (celS) was second. Cthe_0271 encodes a protein of unknown function that consists of a signal peptide, an unknown hydrophobic domain, a 68-residue low-complexity linker region, and the cellulose-binding domain. It is present in a contiguous region of the genome that is undoubtedly regulated for cellulose utilization and includes Cthe_0267 (rsgl2), Cthe_0268 (sigI), Cthe_0269 (celA, encoding a highly expressed cellulase), and Cthe_0274 (celP, encoding another cellulase). Hypothetical protein genes Cthe_1098 and Cthe_1099 were also ranked above the 99th percentile for expression intensity, and the expressed proteins may form some type of heterodimeric complex. The three unknown proteins described here were not previously identified by proteomic approaches, presumably because they do not carry dockerin domains that facilitate isolation by affinity digestion.

Intracellular proteins.

Genes encoding a large number of intracellular proteins were identified by the microarray study, representing another significant new contribution of this work. Other than cluster 1, which had 47% of the genes encoding signal peptides, the remaining clusters had a majority of genes (236 of 270 [87%]) with no recognizable sequence encoding a signal peptide. Correspondingly, the annotations of these genes include diverse intracellular functions, such as fatty acid biosynthesis, cofactor and vitamin biosynthesis, carbon chain rearrangements, glycolysis, ethanol fermentation, and others (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Ethanol fermentation pathway.

The fermentation products lactate, ethanol, formate, and acetate were quantified in a previous chemostat study (31). As growth rate increased on both cellulose and cellobiose, ethanol production increased, while acetate accumulation decreased dramatically. Only trace levels of lactate and formate were detected at all growth rates, and the open design of the chemostat precluded determination of the H2 or CO2 level. The present microarray analysis provides new insight into the expression of enzymes that form these products.

In total, 22 of 28 genes present in the C. thermocellum metabolic pathway identified at KEGG (18) for conversion of cellobiose or other imported oligosaccharides to ethanol ranked above the 80th percentile for expression intensity at the highest growth rate on cellulose, which also led to the highest level of ethanol production. It is notable that when multiple copies of a gene encoding a single enzymatic activity were present, different levels of expression were clearly apparent (e.g., phosphoglycerate mutase, alcohol dehydrogenase) (Table 3). This result demonstrates a hitherto unknown specificity for composition of the ethanol fermentation pathway in C. thermocellum.

TABLE 3.

Percentile-ranked expression of C. thermocellum genes associated with ethanol fermentation pathwaysa,b

| Gene locus | Enzyme | Rank (percentile) for growth on cellulose |

ΔRank (%)c | Rank (percentile) for growth on cellobiose |

ΔRank (%)c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D = 0.013 h−1 | D = 0.206 h−1 | D = 0.025 h−1 | D = 0.156 h−1 | ||||

| Cthe_0143 | Enolase | 92.91 | 99.9 | 7 | 98.56 | 99.7 | 1.2 |

| Cthe_0340 | Ferredoxin | 99.81 | 99.9 | 0 | 99.66 | 99.8 | 0.1 |

| Cthe_0423 | Acetaldehyde/CoA dehydrogenase | 78.80 | 99.7 | 21 | 51.99 | 99.9 | 47.9 |

| Cthe_0349 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 98.87 | 99.4 | 1 | 94.58 | 99.4 | 4.9 |

| Cthe_0139 | Triose phosphate isomerase | 98.31 | 98.7 | 0 | 94.32 | 99.2 | 4.8 |

| Cthe_0138 | 3-Phosphoglycerate kinase | 99.78 | 98.4 | −1 | 91.09 | 99.4 | 8.3 |

| Cthe_2392 | Pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase alpha | 98.37 | 98.0 | 0 | 99.03 | 98.8 | −0.3 |

| Cthe_0137 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 97.37 | 98.0 | 1 | 96.43 | 99.2 | 2.8 |

| Cthe_2390 | Pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase gamma | 96.46 | 98.0 | 2 | 95.52 | 97.1 | 1.6 |

| Cthe_0140 | Phosphoglyceromutase | 95.95 | 96.4 | 0 | 91.03 | 95.9 | 4.9 |

| Cthe_0101 | Iron-containing alcohol dehydrogenase | 92.41 | 96.0 | 4 | 82.35 | 96.2 | 13.9 |

| Cthe_1308 | Pyruvate dikinase | 94.89 | 95.6 | 1 | 96.17 | 96.0 | −0.2 |

| Cthe_0217 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 88.46 | 95.5 | 7 | 87.17 | 97.9 | 10.8 |

| Cthe_2391 | Pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase delta | 95.23 | 93.5 | −2 | 95.64 | 95.7 | 0.1 |

| Cthe_0505 | Pyruvate formate lyase | 95.05 | 91.4 | −4 | 90.28 | 90.5 | 0.3 |

| Cthe_0275 | Cellobiose phosphorylase | 79.30 | 91.0 | 12 | 86.61 | 93.4 | 6.7 |

| Cthe_0506 | Pyruvate formate lyase activating enzyme | 96.99 | 90.0 | −7 | 93.92 | 88.9 | −5.0 |

| Cthe_0347 | Phosphofructokinase | 71.03 | 88.8 | 18 | 73.60 | 91.8 | 18.2 |

| Cthe_2579 | Iron-containing alcohol dehydrogenase | 85.98 | 87.2 | 1 | 73.88 | 88.7 | 14.9 |

| Cthe_0707 | Phosphoglycerate mutase | 14.36 | 84.9 | 70 | 84.23 | 89.7 | 5.4 |

| Cthe_1261 | Phosphofructokinase | 97.52 | 84.0 | −13 | 81.78 | 89.5 | 7.7 |

| Cthe_0946 | Phosphoglycerate mutase | 52.96 | 83.2 | 30 | 66.92 | 84.4 | 17.5 |

| Cthe_2989 | Cellodextrin phosphorylase | 82.66 | 81.6 | −1 | 69.08 | 85.8 | 16.7 |

| Cthe_2938 | Glucokinase | 66.38 | 67.5 | 1 | 58.58 | 77.4 | 18.8 |

| Cthe_1292 | Phosphoglycerate mutase | 19.60 | 49.4 | 30 | 44.87 | 62.9 | 18.0 |

| Cthe_0349 | Iron-containing alcohol dehydrogenase | 79.30 | 47.0 | −32 | 73.57 | 40.4 | −33.1 |

| Cthe_1265 | Phosphoglucomutase | 95.80 | 46.8 | −49 | 52.27 | 50.0 | −2.3 |

| Cthe_1053 | l-Lactate dehydrogenase | 18.16 | 35.8 | 18 | 33.52 | 44.5 | 11.0 |

| Cthe_2449 | Phosphoglycerate mutase | 13.89 | 22.7 | 9 | 25.49 | 28.2 | 2.7 |

| Cthe_1435 | Phosphoglycerate mutase | 85.98 | 14.2 | −72 | 20.41 | 22.9 | 2.5 |

Table entries are sorted according to decreases.

As identified at KEGG PATHWAY database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg) (18).

Expression intensity at highest growth rate minus expression intensity observed at lowest growth rate.

Pyruvate can be converted into each of the three fermentation products identified in the chemostat study. There is one gene encoding lactate dehydrogenase in C. thermocellum (Cthe_1053), and its expression was below the 50th percentile for all growth conditions tested, plausibly corresponding to the low level of lactate detected.

There are three enzyme complexes possibly used for conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) in C. thermocellum. These are pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, pyruvate formate lyase, and pyruvate flavodoxin oxidoreductase. The three structural genes encoding pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase (Cthe_2390, Cthe_2391, and Cthe_2392) were expressed above the 90th percentile at the highest growth rate, corresponding to maximal ethanol production. Interestingly, the ferredoxin gene Cthe_0340 was the 4th most abundantly expressed gene for the fastest growth on cellulose. Since there are only 10 other annotated ferredoxin genes in C. thermocellum, and since these all had expression rankings at the 75th percentile or lower, Cthe_0340 seems to be the most likely electron donor for the pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase reaction.

Acetyl-CoA and formate can also be produced by pyruvate formate lyase (Cthe_0505), an enzyme that requires an activating enzyme (Cthe_0506) to generate an essential active site glycyl radical (33). These two genes were ranked above the 90th percentile during the fastest growth on cellulose. A small amount of formate was detected in the chemostat culture, possibly reflecting intracellular consumption in H2 evolution and folate-dependent C1 metabolism. The importance of folate-dependent C1 metabolism in C. thermocellum is emphasized by the presence of folate-dependent enzymes in the most highly expressed category (e.g., methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase, encoded by Cthe_1093). In contrast, genes for the pyruvate flavodoxin oxidoreductase (Cthe_2794, Cthe_2795, and Cthe_2796) and flavodoxin (Cthe_1597), also capable of using pyruvate as a substrate, were in the lowest quartile of expressed genes under all growth conditions. Thus, the microarray results suggest a prominent role for pyruvate formate lyase in ethanol production.

In C. thermocellum, acetyl-CoA is converted to acetaldehyde by a bifunctional acetaldehyde/CoA dehydrogenase (30). Cthe_0423, encoding this enzyme, was the 10th most highly expressed gene during the fastest growth on cellulose. Moreover, this gene had a 21% increase in expression intensity as the growth rate increased on cellulose, again corresponding to increasing production of ethanol. For conversion of acetaldehyde to ethanol, alcohol dehydrogenase (Cthe_0101) was expressed above the 95th percentile for fastest growth on both cellulose and cellobiose (Table 3). The two other alcohol dehydrogenases (Cthe_2579, ∼85th percentile; Cthe_0394, ∼75th percentile) were expressed at lower levels. Cthe_2579 showed an ∼15% increase in expression intensity ranking for an increased growth rate on cellobiose, while Cthe_0394 showed an ∼30% decrease in expression intensity with both substrates as the growth rate increased (Table 3). Thus, Cthe_0101 and possibly Cthe_2579 may have larger contributions to ethanol production than that of Cthe_0394.

Hydrogenases are also important in the fermentative metabolism of C. thermocellum (29), and three relevant sets of genes are present (Fe-only hydrogenase genes [Cthe_0342, Cthe_0430, and Cthe_3003], Ni-dependent hydrogenase genes [Cthe_0355 and Cthe_3020 to Cthe_3024], and the NiFeS cofactor assembly system [Cthe_3013 to Cthe_3018]). Among these, the Fe-only hydrogenase gene Cthe_0342 was expressed above the 5th percentile under all conditions, while Cthe_0430 changed from the 29th percentile to the 2nd percentile as the growth rate on cellulose increased. The other hydrogenase-related genes were expressed at the ∼25th or ∼55th percentile and exhibited only modest changes in expression intensity (∼±10%) with respect to changes in growth rate or substrate.

Regulation.

Among the 348 differentially expressed genes, 26 had annotated regulatory functions (see Table S6 in the supplemental material). Clusters 1 through 4 contained multiples of these genes, and at least one gene from each cluster had a ranked intensity above the 80th percentile, including genes for adenylate cyclase, AbrB, CarD, CopY, GntR, LacI, MarR, and PadR transcription regulators.

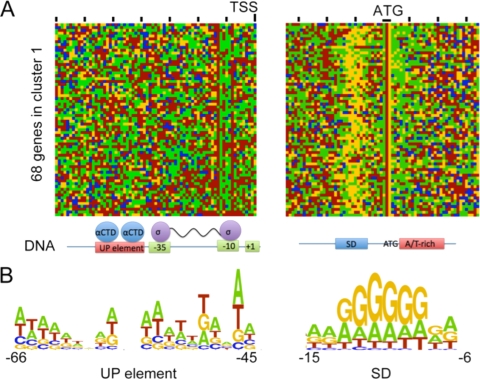

Alignment of nucleotide sequences (19) revealed that >95% of C. thermocellum genes had a recognizable Shine-Dalgarno sequence. The most highly expressed genes, contained primarily in cluster 1, also showed a high propensity for adenine-rich sequences immediately after the start codon (Fig. 4), which has been correlated with elevated expression (5). Analysis of 5′ regions of the cluster 1 genes suggested that these contain a consensus UP element for enhanced interactions with RNA polymerase (6). Interestingly, many of the 343 genes whose expression was not detected did not have a recognizable Shine-Dalgarno sequence.

FIG. 4.

Schematic representation of the upstream regions of 68 highly expressed genes from cluster 1. (A) Visual presentation of the regions upstream of the predicted transcription start site (TSS) and ±30 bp from the start codon, corresponding to potential UP element and Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequences. (B) Nucleotide preferences in the UP element and SD sequences.

Nine membrane-associated RsgI-like proteins were recently identified in C. thermocellum, based on a strong similarity in domain organization and N-terminal sequences to the anti-σI factor RsgI in Bacillus subtilis (17). In the set of 348 genes, there are 6 genes that encode SigI-type sigma factors and 1 that encodes an anti-sigma factor. These are Cthe_0267 (rsgI2), Cthe_0268 (sigI2), Cthe_0269 (celA, encoding a highly expressed cellulase), Cthe_2119 (rsgI6) and Cthe_2120 (sigI6, encoding a putative anti-sigma factor containing an unknown glycoside hydrolase and SigI), Cthe_2975 (sigI8), Cthe_2974 (rsgI8), and Cthe_2972 (xynA, encoding a highly expressed xylanase). In addition, the three RpoE-type sigma-24 factor genes, encoding extracytoplasmic or extreme heat stress sigma factors, had expression patterns corresponding to equation 1. These included Cthe_0890 and Cthe_0891 (encoding a sigma-24 protein and response regulator pair with unknown function), Cthe_1470 and Cthe_1471 (encoding a sigma-24 protein and an unknown glycoside hydrolase), and Cthe_1438 and Cthe_1435 (encoding a sigma-24 protein and a strongly downregulated phosphoglycerate mutase from the glycolysis/ethanol production pathway) (Table 3).

Growth on cellulose.

C. thermocellum can grow rapidly on cellulose, cellopentaose, cellotetraose, cellotriose, and cellobiose (37). Utilization of these soluble hydrolytic products is bioenergetically favorable because after they are transported into the cell, they are hydrolyzed by cellobiose phosphorylase (Cthe_0275) and cellodextrin phosphorylase (Cthe_2989), using a phosphate-dependent mechanism, to generate sugar phosphates without the need to consume ATP (39). The growth rate- and substrate-correlated data set reported here was also examined for new insights about the expression of cellobiose phosphorylase and cellodextrin phosphorylase. These important intracellular enzymes were expressed at the 30th percentile or above for both substrates at both growth rates. More specific information on the expression behavior of these enzymes can be gained by consideration of their individual expression behaviors. Cellobiose phosphorylase was ranked by expression intensity among the top 10% of all genes with both cellulose and cellobiose as substrates at all growth rates, except for the lowest growth rate on cellobiose, where it was ranked at the 13th percentile. In contrast, cellodextrin phosphorylase was ranked only among the top 25% of genes for growth on cellulose at all growth rates and fell to the 35th percentile for the lowest growth rates on cellobiose. At the maximum growth rate on cellobiose, cellobiose phosphorylase was ranked at the 6th percentile by expression intensity, while the expression intensity for cellodextrin phosphorylase rose dramatically, to the 14th percentile.

The expression intensities and changes observed for cellobiose phosphorylase may reflect the high rate of oligosaccharide hydrolysis both inside and outside the cell compared to the lower rates of cellulose hydrolysis and transport of oligosaccharides. Moreover, since the intracellular distribution of oligosaccharides favors cellobiose (36), there is apparently a need for enhanced metabolic throughput to glucose, as would be provided by elevated expression of cellobiose phosphorylase for the most rapid growth on cellobiose. The need for cellodextrin phosphorylase is not clear, particularly if the C. thermocellum enzyme cannot react with cellobiose as reported for the related Clostridium stercorarium enzyme (28). However, one implication of the global mechanism of regulation of gene expression indicated by this work would be that high-level control of the expression of specific genes might not be achieved under controlled substrate conditions such as those given by carbon-limited growth in a chemostat. In natural environments or during growth on more complex materials such as biomass, though, it is reasonable that all manner of oligosaccharides might be available, and thus the relatively high-level expression of cellodextrin phosphorylase provided by growth rate-dependent mechanisms seems entirely reasonable.

In natural habitats, the concentration of soluble hydrolytic products will be low due to their rapid consumption by C. thermocellum and competing microbes. Regulation of gene expression in C. thermocellum by the growth rate is thus consistent with the physiology and ecology of this bacterium, which is specialized to use only cellulose and its soluble oligosaccharide products. In this context, the extent (herein) and specific components (17) of the regulatory systems used to control growth on an insoluble, extracellular substrate represent an important advance in the understanding of microbial cellulose utilization.

Conclusions.

This work provides the first comprehensive examination of gene expression in C. thermocellum under conditions that lead to ethanol production. New insights have been provided into possible proteins involved in the regulation of cellulose utilization, the enzymes involved in this process, and the intracellular conversion of oligosaccharides to ethanol. A powerful advantage of the regression analysis used here is that it has identified new relationships between growth rate, substrate, and gene expression of both known and unknown genes. The extensive microarray data set obtained from this effort, obtained under controlled growth conditions on pure substrates, provides a rich new resource for continued examination of metabolic processes in this important cellulolytic and ethanologenic model organism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the DOE Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (DOE Office of Science grant BER DE-FC02-07ER64494).

We thank Paul J. Weimer for many important contributions to our understanding of microbial cellulose utilization, Kathryn Richmond and Garret Suen for stimulating discussions during the preparation of this work, and Sandra Splinter BonDurant (University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center Gene Expression Center) for technical assistance in microarray preparation. We also thank a reviewer for the suggestion to include an evaluation of the expression of cellobiose phosphorylase, cellodextrin phosphorylase, hydrogenase, sigma factors, and transporters. Other evaluations are also possible with the public availability of these data.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 December 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer, E., Y. Shoham, and R. Lamed. 2006. Cellulose-decomposing bacteria and their enzyme systems. Prokaryotes 2:578-612. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayer, E. A., R. Lamed, B. A. White, and H. J. Flint. 2008. From cellulosomes to cellulosomics. Chem. Rec. 8:364-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolstad, B. M., R. A. Irizarry, M. Astrand, and T. P. Speed. 2003. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19:185-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, S. D., et al. 2007. Construction and evaluation of a Clostridium thermocellum ATCC 27405 whole-genome oligonucleotide microarray. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 137-140:663-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, H., L. Pomeroy-Cloney, M. Bjerknes, J. Tam, and E. Jay. 1994. The influence of adenine-rich motifs in the 3′ portion of the ribosome binding site on human IFN-gamma gene expression in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 240:20-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Condon, C., C. Squires, and C. L. Squires. 1995. Control of rRNA transcription in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 59:623-645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conesa, A., M. J. Nueda, A. Ferrer, and M. Talon. 2006. maSigPro: a method to identify significantly differential expression profiles in time-course microarray experiments. Bioinformatics 22:1096-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demain, A. L., M. Newcomb, and J. H. Wu. 2005. Cellulase, clostridia, and ethanol. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:124-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doi, R. H. 2008. Cellulases of mesophilic microorganisms: cellulosome and noncellulosome producers. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1125:267-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dror, T. W., A. Rolider, E. A. Bayer, R. Lamed, and Y. Shoham. 2003. Regulation of expression of scaffoldin-related genes in Clostridium thermocellum. J. Bacteriol. 185:5109-5116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dror, T. W., A. Rolider, E. A. Bayer, R. Lamed, and Y. Shoham. 2005. Regulation of major cellulosomal endoglucanases of Clostridium thermocellum differs from that of a prominent cellulosomal xylanase. J. Bacteriol. 187:2261-2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emanuelsson, O., S. Brunak, G. von Heijne, and H. Nielsen. 2007. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat. Protoc. 2:953-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold, N. D., and V. J. Martin. 2007. Global view of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome revealed by quantitative proteomic analysis. J. Bacteriol. 189:6787-6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han, S. O., H. Yukawa, M. Inui, and R. H. Doi. 2003. Regulation of expression of cellulosomal cellulase and hemicellulase genes in Clostridium cellulovorans. J. Bacteriol. 185:6067-6075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irizarry, R. A., et al. 2003. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irizarry, R. A., et al. 2003. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4:249-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahel-Raifer, H., et al. 2010. The unique set of putative membrane-associated anti-sigma factors in Clostridium thermocellum suggests a novel extracellular carbohydrate-sensing mechanism involved in gene regulation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 308:84-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanehisa, M., S. Goto, M. Furumichi, M. Tanabe, and M. Hirakawa. 2010. KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:D355-D360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawashima, T., et al. 2000. Archaeal adaptation to higher temperatures revealed by genomic sequence of Thermoplasma volcanium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:14257-14262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar, L., and E. Futschik. 2007. Mfuzz: a software package for soft clustering of microarray data. Bioinformation 2:5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynd, L. R., et al. 2008. How biotech can transform biofuels. Nat. Biotechnol. 26:169-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra, S., P. Beguin, and J. P. Aubert. 1991. Transcription of Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase genes celF and celD. J. Bacteriol. 173:80-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell, W. J. 1998. Physiology of carbohydrate to solvent conversion by clostridia. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 39:31-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morag, E., E. A. Bayer, G. P. Hazlewood, H. J. Gilbert, and R. Lamed. 1993. Cellulase Ss (CelS) is synonymous with the major cellobiohydrolase (subunit S8) from the cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 43:147-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24a.Natal, Y., et al. 2009. Cellodextrin and laminaribiose ABC transporters in Clostridium thermocellum. J. Bacteriol. 191:203-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park, J. S., Y. Matano, and R. H. Doi. 2001. Cohesin-dockerin interactions of cellulosomal subunits of Clostridium cellulovorans. J. Bacteriol. 183:5431-5435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinheiro, B. A., et al. 2009. Functional insights into the role of novel type I cohesin and dockerin domains from Clostridium thermocellum. Biochem. J. 424:375-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raman, B., et al. 2009. Impact of pretreated switchgrass and biomass carbohydrates on Clostridium thermocellum ATCC 27405 cellulosome composition: a quantitative proteomic analysis. PLoS One 4:e5271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichenbecher, M., F. Lottspeich, and K. Bronnenmeier. 1997. Purification and properties of a cellobiose phosphorylase (CepA) and a cellodextrin phosphorylase (CepB) from the cellulolytic thermophile Clostridium stercorarium. Eur. J. Biochem. 247:262-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28a.Roche NimbleGen. 2010. Nimblechip arrays user's guide: gene expression analysis v.5. Roche NimbleGen, Madison, WI.

- 29.Schmidt, O., H. L. Drake, and M. A. Horn. 2010. Hitherto unknown [Fe-Fe]-hydrogenase gene diversity in anaerobes and anoxic enrichments from a moderately acidic fen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:2027-2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith, L. T., and N. O. Kaplan. 1980. Purification, properties, and kinetic mechanism of coenzyme A-linked aldehyde dehydrogenase from Clostridium kluyveri. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 203:663-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevenson, D. M., and P. J. Weimer. 2005. Expression of 17 genes in Clostridium thermocellum ATCC 27405 during fermentation of cellulose or cellobiose in continuous culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4672-4678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strobel, H. J., F. C. Caldwell, and K. A. Dawson. 1995. Carbohydrate transport by the anaerobic thermophile Clostridium thermocellum LQRI. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:4012-4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner, A. F., M. Frey, F. A. Neugebauer, W. Schafer, and J. Knappe. 1992. The free radical in pyruvate formate-lyase is located on glycine-734. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:996-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warner, J. B., and J. S. Lolkema. 2003. CcpA-dependent carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:475-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams, T. I., J. C. Combs, B. C. Lynn, and H. J. Strobel. 2007. Proteomic profile changes in membranes of ethanol-tolerant Clostridium thermocellum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 74:422-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang, Y. H., and L. R. Lynd. 2006. Biosynthesis of radiolabeled cellodextrins by the Clostridium thermocellum cellobiose and cellodextrin phosphorylases for measurement of intracellular sugars. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 70:123-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang, Y. H., and L. R. Lynd. 2005. Regulation of cellulase synthesis in batch and continuous cultures of Clostridium thermocellum. J. Bacteriol. 187:99-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zverlov, V. V., et al. 2010. Hydrolytic bacteria in mesophilic and thermophilic degradation of plant biomass. Eng. Life Sci. 10:1-9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zverlov, V. V., J. Kellermann, and W. H. Schwarz. 2005. Functional subgenomics of Clostridium thermocellum cellulosomal genes: identification of the major catalytic components in the extracellular complex and detection of three new enzymes. Proteomics 5:3646-3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.