Abstract

The Shewanella oneidensis outer membrane β-barrel protein MtrB is part of a membrane-spanning protein complex (MtrABC) which is necessary for dissimilatory iron reduction. Quantitative PCR, heterologous gene expression, and mutant studies indicated that MtrA is required for periplasmic stability of MtrB. DegP depletion compensated for this MtrA dependence.

Dissimilatory iron reduction has been studied extensively since it was discovered in the 1980s to be a microbial respiratory process (11, 13-15). The physiological challenge of this form of respiration is that environmentally relevant ferric iron forms at neutral pH are crystalline iron oxi(hydroxi)des (19). Therefore, dissimilatory iron reduction necessitates an extended respiratory chain through the periplasm and the outer membrane to access the insoluble electron acceptor.

Recently, it was shown that an outer membrane protein complex in Shewanella oneidensis is capable of catalyzing electron transfer over a liposomal membrane (7) and hence in vivo most probably over the outer membrane. This complex consists of the periplasmic c-type cytochrome MtrA, the outer membrane β-barrel protein MtrB, and the outer membrane c-type cytochrome MtrC (7, 17). Mutants in any of these three proteins are either strongly affected in their ability or unable to use ferric iron as the sole electron acceptor (1).

A puzzling phenotype was recently described whereby in an mtrA deletion mutant MtrB could not be detected (7). However, the mechanism of this dependence is not known. This study aims to elucidate the reason for this MtrA dependence for the formation of MtrB.

MtrA is not necessary for MtrB transcription.

mtrA and mtrB are adjacent genes carried in the same operon. The dependence of MtrA for MtrB production could be due to regulatory elements within the mtrA gene. Hence, we determined whether deletion of mtrA affects the quantity of mtrB transcripts. Independent triplicates of wild-type S. oneidensis and a markerless mtrA deletion mutant (20) were grown in minimal medium containing 100 mM fumarate as the electron acceptor and 50 mM lactate as the electron and carbon source. RNA was isolated using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. recA, gyrB, and dnaK were selected as internal reference genes for normalization of the expression ratio of mtrB (Table 1). Fumarate was chosen as the electron acceptor since mtrA mutants are unable to grow under Fe(III)-reducing conditions. Furthermore, the proteomes of chelated iron- and fumarate-grown cells are very similar (18). Transcript quantification revealed that wild-type cells contain a 1.24 ± 0.059-fold higher number of mtrB transcripts than the ΔmtrA mutant. Only a more than 1.5-fold change in the gene expression ratio is biologically significant (6). Therefore, mtrB is transcribed in almost equal amounts in both strains, and MtrA does not seem to be necessary for mtrB transcription or mRNA stability.

TABLE 1.

Primer used in this work

| Primer no. | Primer name | Sequence | Usagea |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BspHI_recA_for | CGGCGGTCATGAGTATCGACGAAAACAAACAG | Construction of pKD46 recA |

| 2 | HindIII_recA_rev | GCCAAGCTTTTAAAAATCTTCGTTAGTTTC | Construction of pKD46 recA |

| 3 | pKD46_exo_int_for | GAGGCACTGGCTGAAATTGG | Sequencing of pKD46 recA |

| 4 | recA_int_rev | GTTTACGTGCGTAGATTGGG | Sequencing of pKD46 recA |

| 5 | mtrB_NcoI_for | CATGCCATGGATGAAATTTAAACTCAATTT | Construction of pBAD mtrBStrep |

| 6 | mtrB_strep_HindIII_rev | GGGAAGCTTTTATTTTTCGAACTGCGGGTGGCTCCAGGCGCCGAGTTTGTAACTCATGCT | Construction of pBAD mtrBStrep |

| 7 | ΔmtrA_up_for | GATCCCCGGGTACCGAGCTCGAATTCGTAACATTCCCAGCGGTCGGTC | mtrA knockout mutant |

| 8 | ΔmtrA_up_rev | AATAGGCTTCCCAATTTGTCCC | mtrA knockout mutant |

| 9 | ΔmtrA_down_for | CGAATTCTGGGACAAATTGGGAAGCCTATTCAGCGCTAAGGAGACGAG | mtrA knockout mutant |

| 10 | ΔmtrA_down_rev | AGCTTGCATGCCTGCAGGTCGACTCTAGAGGTTCGAGGGCATTGAGGC | mtrA knockout mutant |

| 11 | mtrBgen_up_for | ATGATTACGAATTCGAGCTCGGTACCCGGGGGGGTGGCGGATGAACTGTC | Strep epitope knock-in |

| 12 | mtrBgen_up_rev | GGCGCCTGGAGCCACCCGCAGTTCGAAAAATAATCCATTTGCCTCATATGCTC | Strep epitope knock-in |

| 13 | mtrBgen_down_for | TTATTTTTCGAACTGCGGGTGGCTCCAGGCGCCGAGTTTGTAACTCATGCT | Strep epitope knock-in |

| 14 | mtrBgen_down_rev | CGGCCAGTGCCAAGCTTGCATGCCTGCAGGCAAAAGACACCAGTTATGATG | Strep epitope knock-in |

| 15 | ΔdegP_up_for | ATGATTACGAATTCGAGCTCGGTACCCGGGCCATCTCGAGTAAGATCTTTTTG | degP knockout mutant |

| 16 | ΔdegP_up_rev | CTATTCATAACTCCAAATAAGGG | degP knockout mutant |

| 17 | ΔdegP_down_for | CTTATTTGGAGTTATGAATAGTCAATTGGCGAATCTGATC | degP knockout mutant |

| 18 | ΔdegP_down_rev | CGGCCAGTGCCAAGCTTGCATGCCTGCAGGCACTTCAGAGGTGAACTTGC | degP knockout mutant |

| 19 | RT_mtrB_for | CGGCTTAAAACAAGCCTCTG | qRT-PCR |

| 20 | RT_mtrB_rev | CCAAAGGTGGGGTTAAAAGC | qRT-PCR |

| 21 | dnaK_for | ATGGGTAAAATTATTGGTATC | qRT-PCR |

| 22 | dnaK_rev | TTATTTCTTGTCGTCTTTCAC | qRT-PCR |

| 23 | RT_dnaK_for | CGTGACGTGAACATCATGC | qRT-PCR |

| 24 | RT_dnaK_rev | CAGAAACCTGTGGTGGAGC | qRT-PCR |

| 25 | RT_gyrB_for | GCTTGATTGAAGTCGGTGGT | qRT-PCR |

| 26 | RT_gyrB_rev | CGTTTCGCTTCAGAAATGGT | qRT-PCR |

| 27 | RT_recA_for | AGCTATAGCCGCTGAAATCG | qRT-PCR |

| 28 | RT_recA_rev | CCTCGACATTGTCATCATCG | qRT-PCR |

| 29 | HindIII_mtrA_rev | GGGAAGCTTTTAGCGCTGTAATAGCTTGC | Construction of pRSF mtrA mtrBStrep |

| 30 | BspHI_mtrA_for | GAAATATCATGAAGAACTGCCTAAAAATG | Construction of pRSF mtrA mtrBStrep |

| 31 | mtrB_NdeI_for | GGAATTCCATATGAAATTTAAACTCAATTTGATC | Construction of pRSF mtrBStrep |

| 32 | KpnI_mtrBstrep_rev | CGGGGTACCTTATTTTTCGAACTGCGGGTGGCTCCAGGCGCCGAGTTTGTAACTCATGCT | Construction of pRSF mtrBStrep |

| 33 | pRSF_MCS1_for | GGATCTCGACGCTCTCCCT | Sequencing of pRSF mtrA mtrBStrep |

| 34 | pRSF_MCS2_for | TTGTACACGGCCGCATAATC | Sequencing of pRSF mtrBStrep |

| 35 | BL21_ΔdegP_ rev | CAGATTGTAAGGAGAACCCCTTCCCGTTTTCAGGAAGGGGTTGAGGGAGACTAAGCACTTGTCTCCTGTTT | Construction of conditional degP mutant |

| 36 | E.coli_degPtet_for | TTTGTAAAGACGAACAATAAATTTTTACCTTTTGCAGAAACTTTAGTTCGTTTAAGACCCACTTTCACATTTAA | Construction of conditional degP mutant |

qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR.

Heterologous mtrA/mtrB expression in Escherichia coli.

mtrA and mtrB were expressed in E. coli to determine whether the same pattern of MtrA-dependent MtrB production would be detectable. This would suggest that general factors for export, maturation, or localization of β-barrel proteins in Gram-negative bacteria are causative for the observed MtrA-dependent MtrB formation.

E. coli BL21(DE3) was chosen as a host for T7 polymerase-dependent expression of either mtrBStrep alone or mtrA and mtrBStrep using the pRSFDuet-1 expression plasmid (Table 1) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The mtrB gene was modified to contain a Strep-tag epitope to allow for subsequent immunodetection (Table 1). E. coli strains containing either pRSF mtrBStrep or pRSF mtrA mtrBStrep were grown in LB medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3. Subsequently, the cell suspension was transferred to glass bottles and sealed with rubber stoppers to proceed growth under fermentative conditions. Expression of the T7 polymerase gene was induced with 50 μM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), and growth was continued at room temperature for 10 h. MtrB was detected by Western blot analysis using a primary antibody specific for the attached Strep-tag epitope (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

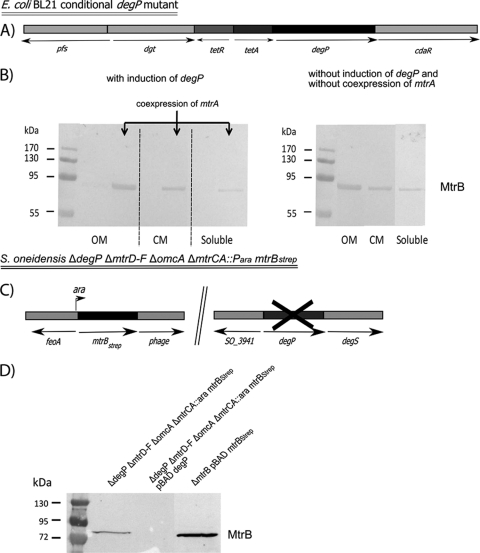

Interestingly, MtrB was not, or only faintly, detectable in membrane fractions when produced without concurrent expression of mtrA even when expressed in E. coli BL21 (Fig. 1). In contrast, MtrA coexpression resulted in a strongly detectable production of MtrB.

FIG. 1.

Western blot of membrane fractions from E. coli BL21 pRSF mtrA mtrBStrep and E. coli BL21 pRSF mtrBStrep strains grown under fermentative conditions in the presence of 50 μM IPTG. A membrane fraction of a ΔmtrB mutant strain complemented with plasmid pBAD mtrBStrep was used as the positive control. Two micrograms was loaded from each E. coli membrane fraction, while 50 μg was loaded from the positive control.

Multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT) analysis of periplasmic protein fractions from S. oneidensis.

Having shown that identical patterns of dependence of MtrB production on MtrA expression is present in E. coli and S. oneidensis, we screened for periplasmic proteases in S. oneidensis that could affect MtrB stability and that are similar to periplasmic proteases of E. coli (2).

Using MudPIT mass spectrometry, 30 μg of a periplasmic protein fraction of S. oneidensis grown under ferric iron-reducing conditions was analyzed. Tryptic digestion followed by an automated 17-step, 34-hour MudPIT program on a linear ion-trap mass spectrometer (LTQ-FT-ICR; Thermo Scientific) was carried out for analysis as previously described (8, 22, 23).

Two proteases with a typical sec leader sequence for export into the periplasm were detected. One of these (SO_3942 [score, 93.13; coverage, 37.6%; 9 peptides detected]) is annotated as a serine protease of the HtrA/DegQ/DegS family, while the other (SO_3411 [score, 15.03; coverage, 3.9%; 2 peptides detected]) is annotated as a putative protease. DegP-dependent protein hydrolysis is ubiquitously distributed in Gram-negative bacteria. It is necessary for the degradation of misfolded outer membrane proteins (9). In S. oneidensis, the SO_3942 gene is located directly upstream of degS. DegS is involved in the σE-dependent stress response which results in upregulation of degP (2). BLAST analysis of SO_3942 revealed a very high similarity to DegP from E. coli (score, 447; E value, 7e−127). Due to this similarity and clustering with degS, we will now refer to S. oneidensis SO_3942 as DegP.

Influence of E. coli degP expression on MtrB stability.

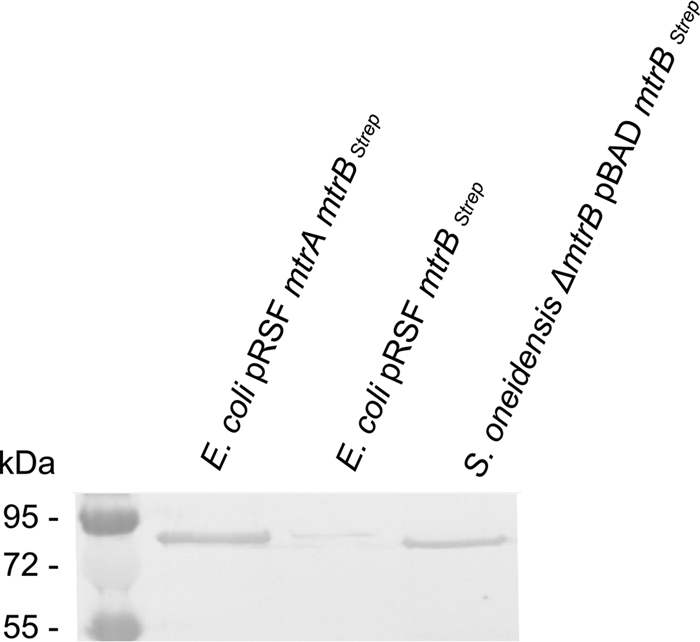

If DegP degrades MtrB in the absence of MtrA, then it should be possible to uncouple this MtrA dependence in the absence of DegP. Following the method described by Datsenko and Wanner (5), a conditional degP mutant in E. coli BL21 was constructed via integration of a tetracycline resistance cassette in place of the native degP promoter, allowing for tet promoter control of degP (Fig. 2A; Table 1). Strains expressing either mtrBStrep or mtrA and mtrBStrep in a conditional degP mutant background were grown as described above. Each of the samples was split into duplicates, and degP expression was induced in half of the flasks via the addition of 0.2 μg ml−1 anhydrotetracycline. Upon induction of degP, MtrB again was detected only when mtrA was coexpressed (Fig. 2B). In contrast, MtrB was detectable even without concurrent expression of MtrA in the absence of degP expression. Moreover, MtrB was, for the most part, correctly localized to the outer membrane and detectable only to a minor extent in the cytoplasmic membrane fraction or the soluble protein pool (Fig. 2B). Membrane separation was achieved using the method described by Leisman et al. (10).

FIG. 2.

(A) Relevant genotype of the E. coli BL21 conditional degP mutant. Heterologous expression of mtrBStrep or mtrA mtrBStrep was achieved using either plasmid pRSF mtrBStrep or pRSF mtrA mtrBStrep and the concomitant addition of 50 μM IPTG. (B) Left, Western blot of protein fractions from E. coli pRSF mtrBStrep and E. coli pRSF mtrA mtrBStrep strains. degP expression was induced with 0.2 mg ml−1anhydrotetracycline. Right, Western blot of protein fractions from the E. coli pRSF mtrBStrep strain. The induction of degP was omitted in this experiment. Two micrograms from each protein fraction was loaded on the gel. OM, outer membrane fraction; CM, cytoplasmic membrane fraction; Soluble, soluble protein fraction. (C) Relevant genotype of the S. oneidensis MR-1 ΔdegP ΔmtrD ΔmtrE ΔmtrF ΔomcA ΔmtrCA::Para mtrBStrep strain. (D) Corresponding Western blot of outer membrane protein fractions derived from S. oneidensis MR-1 ΔdegP ΔmtrD ΔmtrE ΔmtrF ΔomcA ΔmtrCA::Para mtrBStrep cells or its degP complemented version grown under anaerobic conditions with fumarate as the terminal electron acceptor. A membrane fraction of a complemented ΔmtrB mutant strain was used as the positive control. Fifty micrograms of each protein fraction was loaded on the gel.

Uncoupling of the MtrA/MtrB dependence in S. oneidensis.

Finally, we tested whether the same influence of DegP on MtrB stability would also be detectable in S. oneidensis. A markerless degP deletion mutant (Fig. 2C) was constructed in the S. oneidensis ΔmtrD ΔmtrE ΔmtrF ΔomcA ΔmtrCA::Para mtrBStrep strain (3) according to the method described by Schuetz et al. (20). In this strain, mtrBStrep is under pBAD promoter control and contains an extension coding for the Strep-tag epitope (Table 1). As expected, MtrB was detectable in the outer membrane after induction with 1 mM arabinose. Complementation of the degP deletion by degP in trans led to the loss of the MtrB signal, which confirms the results obtained in E. coli (Table 1; Fig. 2D).

Implications.

In this study, we provide evidence for a dual function of the periplasmic c-type cytochrome MtrA. The high heme content and its localization in the periplasm as well as at the outer membrane clearly point toward a role in electron transfer (16, 20). Furthermore, our experiments show that the periplasmic presence of MtrA seems to be necessary for resistance against DegP-based degradation of MtrB. Of note, DegP was shown to form large oligomeric complexes that might be involved in the sequestering of misfolded proteins (4, 12). Still, MtrB was not detectable in the presence of DegP in an mtrA deletion mutant. Therefore, unfolded MtrB does not seem to be sequestered but rather degraded by DegP.

It was shown that β-barrel proteins are usually guided through the periplasm via the interaction with chaperones like SurA or Skp (21). Binding of these chaperones prevents protease hydrolysis. One hypothesis regarding the function of MtrA in MtrB stability could be that MtrA itself binds to unfolded MtrB and may have a scaffold-like function. It was shown that MtrA forms a stable complex with MtrB at the outer membrane (7). Formation of this complex could be initiated in the periplasm when MtrB is in an unfolded state. Efforts to identify periplasmic interactions of soluble MtrB with MtrA and/or other proteins in vivo have been thus far unsuccessful. Nevertheless, this will clearly be a future direction of our research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Melanie Börris and Marisa Fernandez, ZBSA, Freiburg, Germany, for their advice and technical assistance in conducting qualitative PCR, Carmen D. Cordova, Stanford University, for helping with qPCR data analysis, Robert Shanks, University of Pittsburgh, for providing this work with strains and plasmids, and Wolfgang Hähnel, University of Freiburg, for supporting mass spectrometry analysis. J.G. thanks Eric Churchill for fruitful discussion.

This work was supported by the German Science Foundation (GE2085/2-1).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beliaev, A. S., D. A. Saffarini, J. L. McLaughlin, and D. Hunnicutt. 2001. MtrC, an outer membrane decahaem c cytochrome required for metal reduction in Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. Mol. Microbiol. 39:722-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bos, M. P., V. Robert, and J. Tommassen. 2007. Biogenesis of the gram-negative bacterial outer membrane. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61:191-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bücking, C., F. Popp, S. Kerzenmacher, and J. Gescher. 2010. Involvement and specificity of Shewanella oneidensis outer membrane cytochromes in the reduction of soluble and solid-phase terminal electron acceptors. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 306:144-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CastilloKeller, M., and R. Misra. 2003. Protease-deficient DegP suppresses lethal effects of a mutant OmpC protein by its capture. J. Bacteriol. 185:148-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao, H., et al. 2004. Global transcriptome analysis of the heat shock response of Shewanella oneidensis. J. Bacteriol. 186:7796-7803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartshorne, R. S., et al. 2009. Characterization of an electron conduit between bacteria and the extracellular environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:22169-22174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kislinger, T., et al. 2003. PRISM, a generic large scale proteomic investigation strategy for mammals. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2:96-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krojer, T., et al. 2008. Structural basis for the regulated protease and chaperone function of DegP. Nature 453:885-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leisman, G. B., J. Waukau, and S. A. Forst. 1995. Characterization and environmental regulation of outer membrane proteins in Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:200-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovley, D. R., D. E. Holmes, and K. P. Nevin. 2004. Dissimilatory Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 49:219-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Misra, R., M. CastilloKeller, and M. Deng. 2000. Overexpression of protease-deficient DegP(S210A) rescues the lethal phenotype of Escherichia coli OmpF assembly mutants in a degP background. J. Bacteriol. 182:4882-4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myers, C. R., and K. H. Nealson. 1988. Bacterial manganese reduction and growth with manganese oxide as the sole electron acceptor. Science 240:1319-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myers, C. R., and K. H. Nealson. 1990. Respiration-linked proton translocation coupled to anaerobic reduction of manganese(IV) and iron(III) in Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J. Bacteriol. 172:6232-6238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nealson, K. H., and C. R. Myers. 1992. Microbial reduction of manganese and iron: new approaches to carbon cycling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:439-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitts, K. E., et al. 2003. Characterization of the Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 decaheme cytochrome MtrA: expression in Escherichia coli confers the ability to reduce soluble Fe(III) chelates. J. Biol. Chem. 278:27758-27765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross, D. E., et al. 2007. Characterization of protein-protein interactions involved in iron reduction by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:5797-5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruebush, S. S., S. L. Brantley, and M. Tien. 2006. Reduction of soluble and insoluble iron forms by membrane fractions of Shewanella oneidensis grown under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2925-2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroder, I., E. Johnson, and S. de Vries. 2003. Microbial ferric iron reductases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:427-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuetz, B., M. Schicklberger, J. Kuermann, A. M. Spormann, and J. Gescher. 2009. Periplasmic electron transfer via the c-type cytochromes MtrA and FccA of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7789-7796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sklar, J. G., T. Wu, D. Kahne, and T. J. Silhavy. 2007. Defining the roles of the periplasmic chaperones SurA, Skp, and DegP in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 21:2473-2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Washburn, M. P., D. Wolters, and J. R. Yates III. 2001. Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat. Biotechnol. 19:242-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolters, D. A., M. P. Washburn, and J. R. Yates III. 2001. An automated multidimensional protein identification technology for shotgun proteomics. Anal. Chem. 73:5683-5690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]