Abstract

Assessing bacterial behavior in microgravity is important for risk assessment and prevention of infectious diseases during spaceflight missions. Furthermore, this research field allows the unveiling of novel connections between low-fluid-shear regions encountered by pathogens during their natural infection process and bacterial virulence. This study is the first to characterize the spaceflight-induced global transcriptional and proteomic responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic pathogen that is present in the space habitat. P. aeruginosa responded to spaceflight conditions through differential regulation of 167 genes and 28 proteins, with Hfq as a global transcriptional regulator. Since Hfq was also differentially regulated in spaceflight-grown Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Hfq represents the first spaceflight-induced regulator acting across bacterial species. The major P. aeruginosa virulence-related genes induced in spaceflight were the lecA and lecB lectin genes and the gene for rhamnosyltransferase (rhlA), which is involved in rhamnolipid production. The transcriptional response of spaceflight-grown P. aeruginosa was compared with our previous data for this organism grown in microgravity analogue conditions using the rotating wall vessel (RWV) bioreactor. Interesting similarities were observed, including, among others, similarities with regard to Hfq regulation and oxygen metabolism. While RWV-grown P. aeruginosa mainly induced genes involved in microaerophilic metabolism, P. aeruginosa cultured in spaceflight presumably adopted an anaerobic mode of growth, in which denitrification was most prominent. Whether the observed changes in pathogenesis-related gene expression in response to spaceflight culture could lead to an alteration of virulence in P. aeruginosa remains to be determined and will be important for infectious disease risk assessment and prevention, both during spaceflight missions and for the general public.

The microgravity environment associated with spaceflight is unique and has a profound effect on both host and pathogen cells, with potential implications for infectious disease. From the host point of view, astronauts experience a compromised immune response under spaceflight conditions, as reflected in cellular alterations of both the innate and adaptive immune systems (23, 26, 40). Spaceflight has been shown to alter the response of monocytes, isolated from astronauts preflight and in flight, to Gram-negative toxins (27). Further, simulation of aspects of this microgravity-associated decreased immune response, using the hind limb unloaded mouse model, showed an enhanced susceptibility of these animals to bacterial infection (3, 6). From the pathogen's perspective, bacterial obligate and opportunistic pathogens have been found to exhibit enhanced stress resistance phenotypes following growth under both true spaceflight and microgravity analogue conditions (13, 30, 33, 46-49). In response to the spaceflight environment, global transcriptional and proteomic changes were observed for the enteric pathogen Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium grown in the complex medium Lennox L broth base (LB), which were associated with an increased virulence in a murine model of infection (46). Moreover, the small RNA binding protein Hfq was identified as a major transcriptional regulator of S. Typhimurium responses to the spaceflight environment. A subsequent study demonstrated that cultivation of S. Typhimurium in M9 minimal medium abolished the spaceflight-induced virulence (47). While M9 spaceflight cultures of S. Typhimurium exhibited virulence characteristics dramatically different from those in LB, microarray and proteomic analyses revealed a role for Hfq in both the M9 and LB spaceflight stimulons (47). Complementary experiments using the rotating wall vessel (RWV) bioreactor, in which cells are cultured in a microgravity analogue low-fluid-shear environment (i.e., low-shear modeled microgravity [LSMMG]), identified that a low phosphate concentration in LB could be the origin of the spaceflight-induced virulence of S. Typhimurium (47). Interestingly, LSMMG and spaceflight induced similar increased virulence when LB medium was used, and overlapping gene expression profiles, including Hfq and members of the Hfq regulon, were obtained for both growth conditions (47). The latter indicates that molecular and phenotypic similarities between LSMMG and spaceflight conditions could be attributed to the analogous low-fluid-shear environment.

Recently, the global transcriptional response of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 to LSMMG was determined (13). As a ubiquitous organism colonizing both environmental niches and the human body, P. aeruginosa is found in spacecrafts and has previously caused infections in astronauts (8, 24, 35, 43). Cultivation of P. aeruginosa in the LSMMG environment of the RWV induced molecular pathways known to be of importance for virulence, compared to control conditions. In agreement with the microarray data, an increased production of the exopolysaccharide alginate, enhanced resistance to heat and oxidative stress, and a decreased oxygen transfer rate were observed. The alternative sigma factor AlgU and Hfq were both proposed as important mediators of the LSMMG response in P. aeruginosa. In addition, by comparing the behavior of P. aeruginosa cultured in LSMMG to that in a higher-fluid-shear control at body temperature, clinically relevant traits were found to be induced, such as biofilm formation, rhamnolipid production, and the C4-homoserine lactone quorum sensing system (12). Collectively, these data indicate that low fluid shear has an impact on the behavior, and possibly on the pathogenicity, of P. aeruginosa.

Importantly, low-fluid-shear zones are believed to be encountered by pathogens during their natural course of infection in vivo, including in the intestinal, respiratory, and urogenital tracts (12, 34). Therefore, in addition to the importance of spaceflight research for the evaluation of infectious disease risk during long-term missions, this research field has the potential to provide novel insights in the role of fluid shear in virulence and the disease process.

This study describes the global transcriptional and translational responses of P. aeruginosa PAO1 to the microgravity environment of spaceflight. Our aim was to assess whether the microgravity environment of spaceflight could induce virulence traits in P. aeruginosa and if evolutionarily conserved pathways in common with those of spaceflight-grown S. Typhimurium were regulated in a similar fashion. Furthermore, the spaceflight (this study) and LSMMG (13) responses of P. aeruginosa were compared and revealed interesting similarities. In addition to the role of low fluid shear in these observations, the possible involvement of the adopted experimental setup is discussed. The present study is the first to assess the molecular response of an important opportunistic pathogen following growth under actual spaceflight conditions and provides important insights into the evaluation and, eventually, the prevention of P. aeruginosa infections during spaceflight missions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain and growth media.

A derivative of the wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO1 (ATCC 15692), which contained a gentamicin resistance cassette in the attB site, was used for the spaceflight experiment. The gentamicin-resistant strain was constructed through homologous recombination as described previously (38). P. aeruginosa PAO1 was grown in LB medium containing 25 μg/ml gentamicin in the spaceflight hardware (see below) to avoid growth of any contaminants. The bacterial inoculum (1.5 × 108 CFU/ml) in the spaceflight hardware was suspended in 0.5 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Invitrogen) and remained viable but static (not growing) during launch and until 9 days into the flight. After this time, growth was initiated by the addition of LB as described below. Cells were fixed in flight using the RNA and protein fixative RNA Later II (Ambion). At 2.5 h after landing of the space shuttle at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC), samples were recovered and subsequently used for whole-genome transcriptional microarray and proteomic analyses. In each case, the flight culture samples were compared with synchronous culture samples grown under identical conditions on the ground at KSC using coordinated activation and termination times (by means of real-time communications with the shuttle astronauts) in an insulated room that maintained temperature and humidity levels identical to those on the shuttle (orbital environment simulator).

Experimental setup adopted for spaceflight culturing.

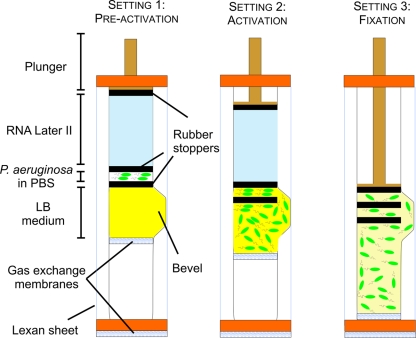

Growth of P. aeruginosa PAO1 was initiated in flight, and cells were cultured in space and on the ground in specialized hardware termed the fluid-processing apparatus (FPA) as described previously (46, 47) (Fig. 1). Briefly, FPAs are glass barrels, containing a bevel on the side, in which rubber stoppers are inserted for compartmentalization. The bottom stopper contained a gas exchange membrane. Glass barrels and rubber stoppers were coated with a silicone lubricant (Sigmacote; Sigma) and autoclaved separately before assembly. The subsequent insertion of rubber stoppers into the FPAs resulted in the creation of three separate compartments which contained, from top to bottom, (i) RNA Later II fixative (2.5 ml), (ii) bacteria suspended in PBS (0.5 ml), and (iii) LB culture medium (2 ml). The last compartment was created at the level of the bevel. Each FPA was loaded into a lexan sheet that contained a gas-permeable membrane at the bottom, and eight FPAs were subsequently loaded into larger containers, termed group activation packs (GAPs). This experimental setup created a triple level of containment for crew safety. At specific time points in flight, an astronaut manually inserted a hand crank into the end of the GAP and turned it, which pushed down on a pressure plate underneath, resulting in a plunging action on the rubber stoppers of each FPA. This plunging action, which allowed for mixing of fluids between different compartments through the bevel, was performed twice in flight. The first plunging action, referred to as activation, served to add LB growth medium to the cells, and the second (following a 25-h growth period) added fixative to preserve samples for gene expression analysis. All phases of the experiment on orbit were conducted at ambient temperature (23°C). Shuttle landing occurred at approximately 58 h postfixation.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of a fluid-processing apparatus (FPA) used as hardware for the spaceflight experiment. In the preactivation setting of the FPA (setting 1), the bacterial inoculum (suspended in PBS) is separated from the culture medium and fixative agent (RNA Later II) through rubber stoppers. The FPAs are brought on board the shuttle in their preactivation setting until activation in low-Earth orbit. Upon activation in flight (setting 2), the plunger is pushed downwards in order to bring the bacteria in contact with the medium, allowing for bacterial growth; the plunger is pushed until the middle stopper is located at the top part of the bevel. After 25 h of bacterial growth (setting 3), the plunger is pushed again in order to bring the middle stopper below the top part of the bevel, which brings the fixative in contact with the bacterial culture.

RNA extraction, labeling, and Affymetrix GeneChip analysis.

Total cellular RNA extraction was performed using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer's instructions. Conversion to fluorescently labeled cDNA, hybridization to Affymetrix GeneChip arrays, and image acquisition were performed as previously described (29). Raw Affymetrix data were normalized and processed utilizing tools identical to those for the study of P. aeruginosa PAO1 under microgravity analogue conditions (13). The Benjamini-Hochberg method was used for multiple-testing correction (7). Only fold change ratios with P values below 0.05 (corrected for multiple testing) were considered statistically significant. Microarray analysis was performed on all three biological replicates.

Protein identification analysis.

Proteins from spaceflight and ground cell lysates were precipitated with acetone and subjected to multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT) analysis using the tandem mass spectrometry (MS)-dual nano-liquid chromatography technique (11, 37). Tandem mass spectra of peptides were analyzed with TurboSEQUEST version 3.1 (18) and XTandem (14) software. Data were further processed and organized using the Scaffold program. A probability threshold of 90% was adopted, and only proteins present in at least two biological replicates were considered expressed. Spectra were also assessed for good quality based on TurboSEQUEST correlation and DeltaCorrelation scores as previously described (11).

Biostatistics.

To calculate the overlap of up- and downregulated genes between P. aeruginosa and S. Typhimurium under spaceflight and simulated microgravity culture conditions, homology was determined using the BLAST software (blastp) (1). Genes in different organisms were defined as orthologues when they fulfilled the following criteria: (i) a cutoff on the BLAST E value of 1e−10, (ii) a minimal alignment coverage of 80% of the shortest DNA or protein sequence, (iii) a minimal sequence identity of 35%, and (iv) appearance as each other's reciprocal best BLAST hit. The statistical significance of the number of overlapping genes between different species and conditions was determined using the hypergeometric distribution method (20).

Microarray data accession number.

The microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=vdmfveeoysewghy&acc=GSE22684) under accession number GSE22684.

RESULTS

P. aeruginosa PAO1 transcriptome and proteome in response to spaceflight. (i) General observations.

Transcriptional analysis of P. aeruginosa PAO1 grown and fixed under spaceflight conditions revealed the induction of 52 genes and the downregulation of 115 genes (2-fold threshold; P < 0.05) compared to those in identical synchronous ground control samples (Table 1). The genes that were differentially regulated under spaceflight conditions were distributed throughout the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome and were often adjacent, indicating organization in transcriptional units (operons). Based on functional classification of differentially expressed genes using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (25), several categories were significantly (P < 0.05) overrepresented in either the up- or downregulated gene group. The functional category that was significantly more represented under spaceflight conditions was nitrogen metabolism, while downregulated gene categories comprised purine and pyrimidine metabolism, fatty acid biosynthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and ribosome synthesis.

TABLE 1.

P. aeruginosa PAO1 genes differentially expressed under spaceflight conditions compared to identical ground controls

| Gene no. | Gene name | Function | Fold change, space/ground | Hfqa | O2a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA0200 | PA0200 | Hypothetical protein | 2.39 | × | × |

| PA0492 | PA0492 | Hypothetical protein | 0.26 | ||

| PA0493 | PA0493 | Acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase | 0.46 | ||

| PA0518 | nirM | Cytochrome c551 precursor | 2.30 | × | × |

| PA0519 | nirS | Nitrite reductase precursor | 2.98 | × | × |

| PA0523 | norC | Nitric oxide reductase subunit C | 5.42 | × | |

| PA0524 | norB | Nitric oxide reductase subunit B | 4.27 | × | × |

| PA0525 | PA0525 | Probable dinitrification protein NorD | 2.54 | × | |

| PA0534 | PA0534 | Hypothetical protein | 2.40 | ||

| PA0567 | PA0567 | Hypothetical protein | 0.47 | ||

| PA0579 | rpsU | 30S ribosomal protein S21 | 0.28 | ||

| PA0595 | ostA | Organic solvent tolerance protein OstA precursor | 0.50 | ||

| PA0788 | PA0788 | Hypothetical protein | 2.08 | ||

| PA0856 | PA0856 | Hypothetical protein | 0.36 | ||

| PA0918 | PA0918 | Cytochrome b561 | 3.32 | × | |

| PA1123 | PA1123 | Hypothetical protein | 0.41 | × | × |

| PA1156 | nrdA | Ribonucleotide diphosphate reductase alpha subunit | 0.48 | × | |

| PA1183 | dctA | C4-dicarboxylate transport protein | 0.48 | × | |

| PA1533 | PA1533 | Hypothetical protein | 0.40 | ||

| PA1552 | PA1552 | Probable cytochrome c | 0.38 | ||

| PA1557 | PA1557 | Probable cytochrome oxidase subunit (cbb3-type) | 0.34 | × | |

| PA1581 | sdhC | Succinate dehydrogenase (C subunit) | 0.34 | ||

| PA1582 | sdhD | Succinate dehydrogenase (D subunit) | 0.38 | ||

| PA1584 | sdhB | Succinate dehydrogenase catalytic subunit | 0.45 | ||

| PA1610 | fabA | 3-Hydroxydecanoyl-acyl carrier protein dehydratase | 0.45 | × | |

| PA1776 | sigX | ECF sigma factor SigX | 0.44 | × | |

| PA1800 | tig | Trigger factor | 0.45 | ||

| PA1863 | modA | Molybdate binding periplasmic protein precursor ModA | 2.04 | ||

| PA1887 | PA1887 | Hypothetical protein | 2.08 | ||

| PA1914 | PA1914 | Hypothetical protein | 3.45 | ||

| PA2003 | bdhA | 3-Hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase | 2.04 | × | |

| PA2007 | maiA | Maleylacetoacetate isomerase | 2.02 | × | |

| PA2009 | hmgA | Homogentisate 1 | 2.24 | ||

| PA2021 | PA2021 | Hypothetical protein | 2.31 | ||

| PA2024 | PA2024 | Probable ring-cleaving dioxygenase | 2.48 | × | |

| PA2225 | PA2225 | Hypothetical protein | 2.03 | × | |

| PA2247 | bkdA1 | 2-Oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase (alpha subunit) | 2.23 | × | |

| PA2248 | bkdA2 | 2-Oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase (beta subunit) | 2.35 | × | |

| PA2300 | chiC | Chitinase | 3.53 | × | × |

| PA2321 | PA2321 | Gluconokinase | 0.25 | ||

| PA2453 | PA2453 | Hypothetical protein | 0.40 | × | |

| PA2570 | palL | PA-I galactophilic lectin | 6.32 | ||

| PA2573 | PA2573 | Probable chemotaxis transducer | 2.09 | × | |

| PA2612 | serS | Seryl-tRNA synthetase | 0.48 | ||

| PA2619 | infA | Translation initiation factor IF-1 | 0.27 | ||

| PA2620 | clpA | ATP binding protease component ClpA | 2.12 | ||

| PA2634 | PA2634 | Isocitrate lyase | 0.44 | × | |

| PA2639 | nuoD | NADH dehydrogenase I chain C | 0.41 | ||

| PA2662 | PA2662 | Hypothetical protein | 2.74 | ||

| PA2743 | infC | Translation initiation factor IF-3 | 0.37 | ||

| PA2747 | PA2747 | Hypothetical protein | 0.46 | × | |

| PA2753 | PA2753 | Hypothetical protein | 2.34 | × | × |

| PA2788 | PA2788 | Probable chemotaxis transducer | 2.10 | ||

| PA2851 | efp | Elongation factor P | 0.34 | × | |

| PA2966 | acpP | Acyl carrier protein | 0.27 | × | |

| PA2970 | rpmF | 50S ribosomal protein L32 | 0.27 | ||

| PA2971 | PA2971 | Hypothetical protein | 0.33 | ||

| PA3001 | PA3001 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.47 | ||

| PA3162 | rpsA | 30S ribosomal protein S1 | 0.38 | ||

| PA3307 | PA3307 | Hypothetical protein | 3.12 | ||

| PA3361 | lecB | Fucose binding lectin PA-IIL | 5.12 | ||

| PA3369 | PA3369 | Hypothetical protein | 0.46 | × | |

| PA3391 | nosR | Regulatory protein NosR | 2.09 | × | |

| PA3392 | nosZ | Nitrous oxide reductase precursor | 2.65 | × | |

| PA3415 | PA3415 | Probable dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase | 2.75 | ||

| PA3416 | PA3416 | Probable pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component | 2.17 | × | |

| PA3417 | PA3417 | Probable pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component | 3.26 | × | |

| PA3418 | ldh | Leucine dehydrogenase | 3.20 | × | |

| PA3440 | PA3440 | Hypothetical protein | 0.47 | ||

| PA3476 | rhlI | Autoinducer synthesis protein RhlI | 0.48 | × | |

| PA3479 | rhlA | Rhamnosyltransferase chain A | 2.75 | × | × |

| PA3520 | PA3520 | Hypothetical protein | 4.03 | × | × |

| PA3531 | bfrB | Bacterioferritin | 0.47 | ||

| PA3575 | PA3575 | Hypothetical protein | 0.40 | ||

| PA3621 | fdxA | Ferredoxin I | 0.36 | × | |

| PA3644 | lpxA | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine acyltransferase | 0.49 | ||

| PA3645 | fabZ | (3R)-Hydroxymyristoyl acyl carrier protein dehydratase | 0.38 | ||

| PA3646 | lpxD | UDP-3-O-(3-hydroxymyristoyl) glucosamine N-acyltransferase | 0.40 | ||

| PA3655 | tsf | Elongation factor Ts | 0.34 | ||

| PA3656 | rpsB | 30S ribosomal protein S2 | 0.32 | ||

| PA3686 | adk | Adenylate kinase | 0.47 | × | |

| PA3723 | PA3723 | Probable flavin mononucleotide oxidoreductase | 2.49 | × | |

| PA3742 | rplS | 50S ribosomal protein L19 | 0.42 | ||

| PA3743 | trmD | tRNA [guanine-N(1)-]-methyltransferase | 0.33 | ||

| PA3744 | rimM | 16S rRNA-processing protein | 0.29 | ||

| PA3745 | rpsP | 30S ribosomal protein S16 | 0.25 | ||

| PA3785 | PA3785 | Hypothetical protein | 2.14 | ||

| PA3795 | PA3795 | Probable oxidoreductase | 0.46 | × | |

| PA3807 | ndk | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | 0.38 | ||

| PA3814 | iscS | l-Cysteine desulfurase (pyridoxal phosphate-dependent) | 0.47 | ||

| PA3834 | valS | Valyl-tRNA synthetase | 0.50 | ||

| PA3920 | PA3920 | Probable metal-transporting P-type ATPase | 2.39 | × | |

| PA4031 | ppa | Inorganic pyrophosphatase | 0.48 | × | |

| PA4053 | ribH | Riboflavin synthase subunit beta | 0.50 | ||

| PA4220 | PA4220 | Hypothetical protein | 2.47 | × | |

| PA4238 | rpoA | DNA-directed RNA polymerase alpha subunit | 0.42 | ||

| PA4239 | rpsD | 30S ribosomal protein S4 | 0.31 | ||

| PA4240 | rpsK | 30S ribosomal protein S11 | 0.38 | ||

| PA4241 | rpsM | 30S ribosomal protein S13 | 0.34 | ||

| PA4242 | rpmJ | 50S ribosomal protein L36 | 0.16 | ||

| PA4243 | secY | Preprotein translocase SecY | 0.31 | ||

| PA4245 | rpmD | 50S ribosomal protein L30 | 0.36 | ||

| PA4246 | rpsE | 30S ribosomal protein S5 | 0.41 | ||

| PA4247 | rplR | 50S ribosomal protein L18 | 0.28 | ||

| PA4248 | rplF | 50S ribosomal protein L6 | 0.36 | ||

| PA4249 | rpsH | 30S ribosomal protein S8 | 0.37 | ||

| PA4252 | rplX | 50S ribosomal protein L24 | 0.34 | ||

| PA4254 | rpsQ | 30S ribosomal protein S17 | 0.49 | ||

| PA4257 | rpsC | 30S ribosomal protein S3 | 0.44 | ||

| PA4258 | rplV | 50S ribosomal protein L22 | 0.44 | ||

| PA4259 | rpsS | 30S ribosomal protein S19 | 0.37 | ||

| PA4260 | rplB | 50S ribosomal protein L2 | 0.49 | ||

| PA4261 | rplW | 50S ribosomal protein L23 | 0.37 | ||

| PA4262 | rplD | 50S ribosomal protein L4 | 0.32 | ||

| PA4263 | rplC | 50S ribosomal protein L3 | 0.32 | ||

| PA4266 | fusA1 | Elongation factor G | 0.38 | ||

| PA4267 | rpsG | 30S ribosomal protein S7 | 0.39 | ||

| PA4268 | rpsL | 30S ribosomal protein S12 | 0.25 | ||

| PA4271 | rplL | 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 | 0.48 | ||

| PA4272 | rplJ | 50S ribosomal protein L10 | 0.38 | ||

| PA4274 | rplK | 50S ribosomal protein L11 | 0.49 | ||

| PA4296 | PA4296 | Probable two-component response regulator | 2.37 | ||

| PA4306 | PA4306 | Hypothetical protein | 2.65 | × | |

| PA4351 | PA4351 | Probable acyltransferase | 2.40 | × | |

| PA4352 | PA4352 | Hypothetical protein | 2.27 | × | × |

| PA4386 | groES | Cochaperonin GroES | 0.50 | ||

| PA4425 | gmhA | Phosphoheptose isomerase | 0.43 | ||

| PA4430 | PA4430 | Probable cytochrome b | 0.35 | ||

| PA4431 | PA4431 | Probable iron-sulfur protein | 0.47 | ||

| PA4432 | rpsI | 30S ribosomal protein S9 | 0.46 | ||

| PA4433 | rplM | 50S ribosomal protein L13 | 0.20 | × | |

| PA4482 | gatC | Aspartyl/glutamyl-tRNA amidotransferase subunit C | 0.35 | ||

| PA4563 | rpsT | 30S ribosomal protein S20 | 0.17 | ||

| PA4568 | rplU | 50S ribosomal protein L21 | 0.22 | ||

| PA4569 | ispB | Octaprenyl-diphosphate synthase | 0.49 | × | |

| PA4602 | glyA3 | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | 0.40 | ||

| PA4608 | PA4608 | Hypothetical protein | 2.11 | ||

| PA4610 | PA4610 | Hypothetical protein | 2.70 | × | |

| PA4633 | PA4633 | Probable chemotaxis transducer | 2.03 | × | |

| PA4671 | PA4671 | 50S ribosomal protein L25 | 0.37 | ||

| PA4692 | PA4692 | Hypothetical protein | 2.02 | ||

| PA4702 | PA4702 | Hypothetical protein | 3.56 | ||

| PA4739 | PA4739 | Hypothetical protein | 0.49 | × | × |

| PA4740 | pnp | Polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase | 0.43 | ||

| PA4743 | rbfA | Ribosome binding factor A | 0.48 | ||

| PA4847 | accB | Biotin carboxyl carrier protein (BCCP) | 0.38 | ||

| PA4848 | accC | Biotin carboxylase | 0.46 | ||

| PA4880 | PA4880 | Probable bacterioferritin | 0.46 | × | |

| PA4935 | rpsF | 30S ribosomal protein S6 | 0.48 | ||

| PA4944 | hfq | RNA binding protein Hfq | 0.48 | ||

| PA5049 | rpmE | 50S ribosomal protein L31 | 0.28 | ||

| PA5054 | hslU | ATP-dependent protease ATP-binding subunit | 0.49 | ||

| PA5067 | hisE | Phosphoribosyl-ATP pyrophosphatase | 0.49 | ||

| PA5069 | tatB | Sec-independent translocase | 0.35 | ||

| PA5078 | PA5078 | Hypothetical protein | 0.45 | ||

| PA5117 | typA | Regulatory protein TypA | 0.44 | ||

| PA5128 | secB | Export protein SecB | 0.45 | ||

| PA5276 | lppL | Lipopeptide LppL precursor | 0.35 | ||

| PA5316 | rpmB | 50S ribosomal protein L28 | 0.27 | ||

| PA5355 | glcD | Glycolate oxidase subunit GlcD | 2.51 | × | |

| PA5460 | PA5460 | Hypothetical protein | 2.21 | × | |

| PA5490 | cc4 | Cytochrome c4 precursor | 0.47 | ||

| PA5491 | PA5491 | Probable cytochrome | 0.35 | × | |

| PA5555 | atpG | ATP synthase subunit C | 0.33 | ||

| PA5557 | atpH | ATP synthase subunit D | 0.45 | ||

| PA5569 | rnpA | RNase P | 0.41 | ||

| PA5570 | rpmH | 50S ribosomal protein L34 | 0.22 |

Genes that are part of the Hfq regulon or involved in anaerobic/microaerophilic metabolism are indicated with “×” (n = 3; P < 0.05; fold change, ≥2.

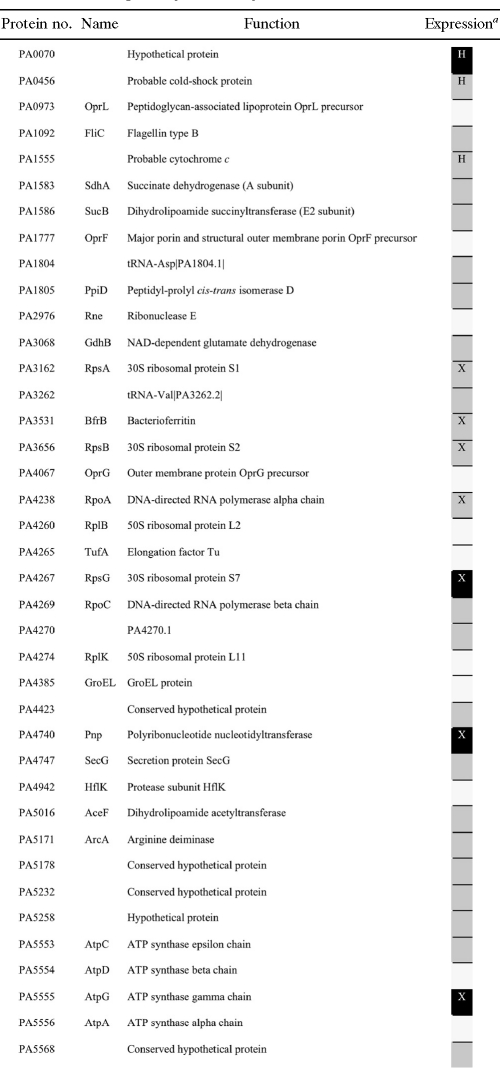

By means of MudPIT analysis, 40 proteins were identified in ground and spaceflight samples (present in at least two replicates), among which 28 were differentially expressed (Table 2). Seven of these 28 proteins were also differentially regulated at the transcriptional level.

TABLE 2.

Proteome of P. aeruginosa PAO1 grown under spaceflight versus ground conditions

a Black cells indicate the proteins expressed in flight samples and not in ground samples, gray stands for proteins expressed in ground samples and not in flight samples, and white cells are for proteins expressed in both ground and spaceflight samples. X, proteins that were also found differentially expressed at the transcriptomic level; H, proteins under the control of Hfq.

(ii) Hfq and the Hfq regulon.

The gene encoding the RNA binding protein Hfq and genes under the control of Hfq were differentially expressed under spaceflight conditions. More specifically, 13.4% of the genes from the previously described Hfq regulon (42) were induced (17 of 38 genes) or downregulated (21 of 38 genes) in response to spaceflight, accounting for 23% of the P. aeruginosa spaceflight stimulon. The overlap between the spaceflight data set and the Hfq regulon was significant (P < 0.05), indicating that this transcriptional regulator, at least in part, mediated the spaceflight response of P. aeruginosa. While the downregulation of Hfq under spaceflight conditions presumably resulted in the downregulation of genes under positive control of Hfq (such as sigX, adk, and fabA) and the upregulation of genes under negative control of Hfq (such as bkdA2, bdhA, and glcC), other genes showed a direction of fold change opposite to what would be expected based upon the described Hfq regulon. Examples include the upregulation of nirS, chiC, and rhlA, which have been documented to be under positive control of Hfq under conventional culture conditions (42). This finding indicates that other (post)transcriptional or posttranslational regulators (or regulatory networks) may have played a role in the differential expression of these genes in the microgravity environment of spaceflight. Additionally, three proteins whose mRNA expression levels are controlled by Hfq (i.e., PA0070, PA0456, and PA1555) were found to be differentially expressed at the proteomic level.

(iii) Anaerobic metabolism.

The majority of genes that were upregulated under spaceflight conditions (60%) were associated with growth under anaerobic conditions (Table 1) (19). Furthermore, 13% of the genes that were downregulated in spaceflight are known to be downregulated during anaerobic growth (19). Using hypergeometric distribution, the overlap between the genes induced under anaerobic conditions and the genes upregulated in spaceflight was significant (P < 0.05). Similarly, a significant overlap was found between genes downregulated during anaerobic growth and in spaceflight. Only a few genes which are typically induced under microaerophilic growth conditions (2) (i.e., PA4306, PA4352, rhlI, and PA1123) were differentially expressed in spaceflight compared to synchronous ground controls. Remarkably, genes involved in denitrification were among those with the highest fold inductions within this category. While genes encoding the nitrate reductase were not induced significantly, the mRNAs of genes encoding nitrite (nirMS), nitric oxide (norBC), and nitrous oxide reductases (nosRZ) were more abundant in spaceflight-grown P. aeruginosa PAO1.

Proteomic analysis of the P. aeruginosa cells grown in spaceflight revealed that 7 of the 28 differentially expressed proteins play a role in anaerobic growth. The downregulation of ArcA, an enzyme involved in the fermentation of arginine, was observed, as well as the downregulation of CcoP2 (PA1555) (10), a cytochrome with high affinity for oxygen. The latter is typically induced under microaerophilic conditions but not in the anaerobic mode of growth of P. aeruginosa (2).

(iv) Virulence factors.

The transcripts of several genes encoding known P. aeruginosa PAO1 virulence factors were induced in spaceflight samples compared to the ground controls. Among others, the genes encoding the lectins PA-I and PA-IIL (lecA and lecB, respectively), the chitinase-encoding gene chiC, and the rhamnolipid-encoding gene rhlA were significantly induced. The lecA gene showed the highest fold induction in the gene list (6.3-fold). On the other hand, downregulation of genes encoding heat shock proteins (groES and hslU) and the N-butanoyl-l-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL) synthase (rhlI) was observed. As mentioned above, hfq, which is a transcriptional regulator involved in the virulence of P. aeruginosa, was downregulated during spaceflight.

(v) Other functional categories.

Of 115 genes that were downregulated under spaceflight conditions, 40 are involved in the synthesis of ribosomes. Genes involved in the dehydrogenation of succinate to fumarate (i.e., sdhBCD) and ATP synthesis (atpGH) were less expressed in spaceflight-grown P. aeruginosa PAO1.

Comparative bioinformatic analysis of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 and S. Typhimurium spaceflight stimulons.

In order to compare the gene expression profiles of P. aeruginosa (this study) and S. Typhimurium (46) following exposure to spaceflight conditions, orthologues of P. aeruginosa genes were identified in the S. Typhimurium genome. Of 167 differentially expressed genes in P. aeruginosa, 102 orthologues were identified in S. Typhimurium, among which 92 (of 115) belonged to the downregulated group and 10 (of 52) belonged to the upregulated gene list.

A significant overlap was found for the downregulated genes of the two bacteria (P < 0.05) (Table 3). More specifically, 15 genes showed a common lower transcription in the spaceflight samples and in the synchronous ground controls, among which 9 encoded ribosomal subunits. Interestingly, hfq and bfrB (encoding bacterioferritin) were part of the overlapping genes and were identified as key role players in both the spaceflight- and LSMMG-induced responses of S. Typhimurium (46, 49). Despite the observation that the overlap between spaceflight-grown P. aeruginosa and S. Typhimurium was significant, it is rather limited. Indeed, only 16% of the S. Typhimurium orthologues in P. aeruginosa were found to be commonly downregulated between the two bacteria. No overlap could be identified for the upregulated genes of P. aeruginosa and S. Typhimurium under spaceflight conditions. This is presumably because, in part, of the low presence of P. aeruginosa orthologues (for the upregulated genes) in the S. Typhimurium genome and because fewer genes were upregulated in response to spaceflight for both of these organisms.

TABLE 3.

Overlap of genes differentially regulated in both spaceflight-grown P. aeruginosa and S. Typhimurium compared to identical ground controls

| P. aeruginosa gene no. | Orthologue in S. Typhimurium | Gene name | Gene function |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA2966 | STM1196 | acpP | Acyl carrier protein |

| PA3531 | STM3443 | bfrB | Bacterioferritin |

| PA3656 | STM0216 | rpsB | 30S ribosomal protein S2 |

| PA3744 | STM2675 | rimM | 16S rRNA-processing protein |

| PA4031 | STM4414 | ppa | Inorganic pyrophosphatase |

| PA4053 | STM0417 | ribH | Riboflavin synthase subunit beta |

| PA4248 | STM3425 | rplF | 50S ribosomal protein L6 |

| PA4259 | STM3436 | rpsS | 30S ribosomal protein S19 |

| PA4261 | STM3438 | rplW | 50S ribosomal protein L23 |

| PA4262 | STM3439 | rplD | 50S ribosomal protein L4 |

| PA4268 | STM3448 | rpsL | 30S ribosomal protein S12 |

| PA4433 | STM3345 | rplM | 50S ribosomal protein L13 |

| PA4935 | STM4391 | rpsF | 30S ribosomal protein S6 |

| PA4944 | STM4361 | hfq | RNA binding protein Hfq |

| PA5128 | STM3701 | secB | Export protein SecB |

Comparative bioinformatic analysis of the P. aeruginosa spaceflight and LSMMG stimulons.

A small, but significant (P < 0.05), overlap of genes commonly upregulated in spaceflight- and LSMMG-grown P. aeruginosa was identified. These genes encode the hypothetical protein PA0534, a protein involved in microaerophilic/anaerobic metabolism (PA0200), the ATP binding protease component ClpA, and a hypothetical protein belonging to the Hfq regulon (PA2753). On the other hand, 35 genes that were found to be upregulated in LSMMG were downregulated under spaceflight conditions. The majority of these genes (27 of 35) could be categorized as being involved in the synthesis of ribosomes. Additionally, genes encoding citric acid cycle proteins (sdhB, PA2634), bacterioferritin (bfrB), a translational elongation factor (fusA1), a heat shock protein (HslU), the sigma factor RpoA, a hypothetical protein (PA0856), and a protein involved in glycolysis (PA3001) were downregulated in response to spaceflight culture but upregulated in LSMMG.

In our previous study (13), LSMMG was found to induce several genes encoding hypothetical proteins in P. aeruginosa PAO1. Among these, only one hypothetical protein (i.e., PA2737) had not been reported as being differentially regulated under any studied condition and was proposed as potentially specific to the low-fluid-shear conditions of LSMMG. Interestingly, PA2737 was also significantly upregulated in spaceflight, albeit below the 2-fold threshold (1.7-fold).

DISCUSSION

Assessing the behavior and virulence potential of obligate and opportunistic pathogens aboard spacecraft and the International Space Station (ISS) is of central importance to evaluate the risk for infectious disease in the context of long-term manned missions. Furthermore, since bacteria encounter microgravity analogue low-fluid-shear forces in the host during their natural course of infection, bacterial spaceflight research can provide novel insights into the in vivo infection process. Indeed, spaceflight increased the virulence of S. Typhimurium, while global gene expression profiling revealed a general downregulation of key virulence genes in this pathogen (46, 47). The present study demonstrated for the first time that the opportunistic pathogen P. aeruginosa responded to culture in the microgravity environment of spaceflight through differential regulation of 167 genes and 28 proteins. A significant part of the spaceflight stimulon was under the control of the RNA binding protein Hfq. Hfq is important for the virulence and stress resistance of several (opportunistic) pathogens, including P. aeruginosa PAO1 (17, 39, 41), by modulating the function and stability of small regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) and interfering with their interactions with mRNAs (reviewed in references 31 and 44). Interestingly, Hfq was also found to be an important regulator in the responses of (i) P. aeruginosa to microgravity analogue low-fluid-shear conditions (LSMMG, using the RWV bioreactor) and (ii) S. Typhimurium to actual spaceflight and LSMMG conditions (13, 46, 49). Hence, Hfq is the first transcriptional regulator ever shown to be commonly involved in the spaceflight and LSMMG responses of two bacterial species.

Among the P. aeruginosa genes with the highest fold inductions under spaceflight conditions were the genes encoding the lectins LecA and LecB. Lectins bind galactosides, play a role in the bacterial adhesion process to eukaryotic cells, and are thus important virulence factors in P. aeruginosa (21, 22). P. aeruginosa lectins have cytotoxic effects in human peripheral lymphocytes and respiratory epithelial cells in vitro and increase alveolar barrier permeability in vivo (4, 9). Lectin production in P. aeruginosa is regulated through the N-butanoyl-l-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL) quorum-sensing system (50), which has been previously reviewed (45). However, the downregulation of rhlI, the gene encoding the C4-HSL synthase, under spaceflight conditions was unexpected. Nevertheless, rhlA, which is dependent on C4-HSL quorum-sensing regulation and encodes the rhamnosyltransferase I involved in rhamnolipid surfactant biosynthesis, was induced during spaceflight culture. Rhamnolipids are glycolipidic surface-active molecules that have cytotoxic and immunomodulatory effects in eukaryotic cells (5, 15, 32, 36). Interestingly, rhamnolipids and rhlA transcripts were also found in P. aeruginosa in larger amounts under low-fluid-shear compared to higher-fluid-shear growth conditions, using the RWV bioreactor (12). These data indicate that rhamnolipid production could be induced upon sensing of low fluid shear.

Gene expression profiles of P. aeruginosa grown under spaceflight conditions also revealed the differential regulation of a significant fraction of genes involved in growth under oxygen-limiting conditions. Spaceflight induced mainly genes involved in anaerobic metabolism, which was reinforced by a lower expression in spaceflight samples of CcoP2, a cytochrome with high affinity for oxygen that is typically induced under microaerophilic conditions (2, 10). At the time of measurement, the most prominent way to cope with the apparent oxygen shortage under spaceflight conditions seemed to occur through denitrification and not through fermentation. Indeed, under oxygen-limiting conditions, P. aeruginosa switches to anaerobic respiration in the presence of the alternative electron acceptor nitrate or nitrite (16). The downregulation of ArcA, a protein involved in arginine fermentation, accentuates that fermentation was presumably not activated in spaceflight-grown bacteria.

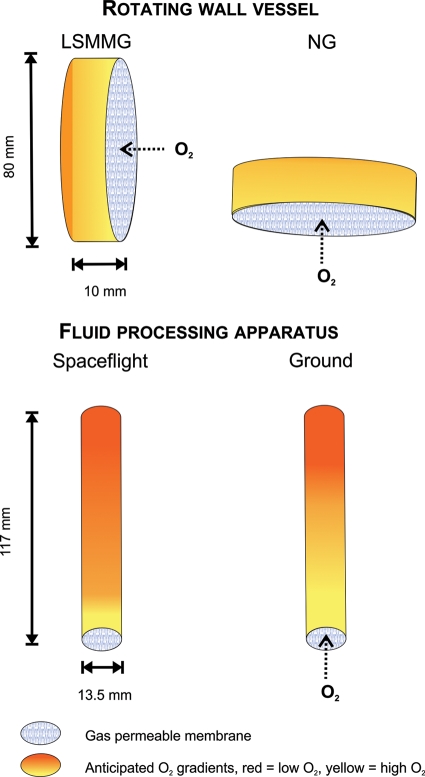

When comparing the gene expression profiles of P. aeruginosa grown in spaceflight and P. aeruginosa grown in LSMMG, a limited but significant overlap was found. Besides the role of Hfq and its regulon in the response of P. aeruginosa PAO1 to both spaceflight and LSMMG (see above), a significant fraction of genes involved in both microaerophilic and anaerobic metabolism were commonly induced. In contrast to P. aeruginosa grown under spaceflight conditions, LSMMG-grown P. aeruginosa induced genes involved in arginine and pyruvate fermentation, while denitrification did not appear to play a role in the LSMMG response of this bacterium. The observation that spaceflight samples were presumably more deprived of oxygen than LSMMG-grown bacteria, compared to their respective controls, could be explained by the fact that actual spaceflight conditions are characterized by even lower fluid shear levels than LSMMG conditions. Indeed, due to the absence of convection currents in microgravity, oxygen limitation will be more pronounced in space than in LSMMG. Furthermore, the role of the experimental setup needs to be considered. As depicted in Fig. 2, cells grown in the bioreactors used for growth of P. aeruginosa in LSMMG and spaceflight have different oxygen availabilities. While the bioreactors have a gas-permeable membrane, the membrane surface-to-volume ratio of FPA bioreactors (used in spaceflight) is 12 times lower than that of the RWVs (LSMMG) [based on the formula πr2/(πr2 × h) or 1/h, with r = radius and h = height]. Hence, oxygen availability overall will be higher in RWVs than in the FPA devices. It also needs to be mentioned that despite differences in aeration and fluid shear between the spaceflight and LSMMG studies, the RWV mimics only certain aspects of the spaceflight environment. Indeed, enhanced irradiation and vibration or potential direct effects of microgravity (such as effects on the cell or cellular components instead of on the extracellular environment) during spaceflight could lead to differences in gene and protein expression profiles between spaceflight and LSMMG-grown P. aeruginosa. Accordingly, the RWV bioreactor was unable to mimic the complete repertoire of spaceflight-induced alterations in P. aeruginosa.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the different hardware used for cultivation of P. aeruginosa under microgravity analogue conditions (LSMMG versus control, using RWV bioreactors) and under spaceflight conditions (spaceflight versus ground, using FPA devices). The anticipated oxygen gradients under each condition are indicated, ranging from high (yellow) to low (red) oxygen levels. The oxygen gradient estimations are based on (i) the low-fluid-shear conditions encountered under the different conditions and (ii) the surface-to-volume ratio of RWV and FPA bioreactors.

Since the present study was conducted by growing P. aeruginosa in a liquid environment under spaceflight conditions, our results are relevant mainly to the assessment of bacterial virulence in fluid niches of the spacecraft. Indeed, astronauts are in regular contact with water-containing sources that could be contaminated with P. aeruginosa, such as drinking water, rinseless shampoo, toothpaste, mouthwash, and water for laundry. Similarly, water-related sites in the hospital environment are most likely to harbor P. aeruginosa (e.g., faucets, showers, medication, disinfectants, mouthwash, and other hygiene products) and are at the origin of a significant number of nosocomial infections (28). Furthermore, P. aeruginosa is occasionally part of the normal human flora of the mouth, pharynx, anterior urethra, and lower gastrointestinal tract. In these regions of the human body, P. aeruginosa is present in a fluid environment, which will be affected by microgravity and will presumably result in the exposure of P. aeruginosa to lower-fluid-shear conditions than on Earth.

This study was the first to characterize the comprehensive transcriptional and translational responses of an opportunistic pathogen that is frequently found in the space habitat. We demonstrated that spaceflight conditions activated pathways in P. aeruginosa that have been shown previously to be involved in the in vivo infection process. However, the regulation of several of these pathways appears to be differentially controlled during spaceflight compared to conventional culture. Hfq was put forward as a main transcriptional regulator in the spaceflight response of P. aeruginosa, therefore representing the first transcriptional regulator commonly involved in the spaceflight responses of different bacterial species. We also identified interesting similarities and differences between P. aeruginosa grown in spaceflight and under the LSMMG conditions of the RWV. Despite the limited overlap of identical genes between spaceflight- and LSMMG-grown P. aeruginosa, it was observed that different genes of the same regulon or stimulon could be induced or downregulated in spaceflight and LSMMG. The experimental setup was proposed as one of the putative factors at the origin of the oxygen-related transcriptional differences between LSMMG culture in the RWV bioreactor and spaceflight-cultured P. aeruginosa in the FPAs. These data emphasize the importance of using identical hardware for spaceflight experiments and ground simulations, especially when oxygen is a limiting factor. In addition, differences in fluid shear and other environmental conditions (such as irradiation) between actual microgravity and LSMMG need to be considered when comparing bacterial responses to the two test conditions. This study represents an important step in understanding the response of bacterial opportunistic pathogens to the unique spaceflight environment. Furthermore, it allows assessment of the role that low-fluid-shear regions found in the human body play in the regulation of bacterial virulence. It remains to be determined whether the phenotype of P. aeruginosa acquired under spaceflight conditions will effectively lead to increased pathogenicity, as was observed for S. Typhimurium. This will be an important consideration and key area of future study in order to further assess the risk for infectious disease during long-term missions.

Acknowledgments

We thank all supporting team members at Kennedy Space Center, Johnson Space Center, Ames Research Center, Marshall Spaceflight Center, and BioServe Space Technologies, the crew of STS-115, Neal Pellis, Roy Curtiss III, and Joseph Caspermeyer. We also thank Kerstin Höner zu Bentrup for training team members on use of the flight hardware.

This work was supported by NASA grant NCC2-1362 to C.A.N., the Arizona Proteomics Consortium (supported by NIEHS grant ES06694 to the SWEHSC), NIH/NCI grant CA023074 to the AZCC, and the BIO5 Institute of the University of Arizona.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., et al. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Ortega, C., and C. S. Harwood. 2007. Responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to low oxygen indicate that growth in the cystic fibrosis lung is by aerobic respiration. Mol. Microbiol. 65:582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aviles, H., T. Belay, K. Fountain, M. Vance, and G. Sonnenfeld. 2003. Increased susceptibility to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection under hindlimb-unloading conditions. J. Appl. Physiol. 95:73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajolet-Laudinat, O., et al. 1994. Cytotoxicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa internal lectin PA-I to respiratory epithelial cells in primary culture. Infect. Immun. 62:4481-4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bedard, M., et al. 1993. Release of interleukin-8, interleukin-6, and colony-stimulating factors by upper airway epithelial cells: implications for cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 9:455-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belay, T., H. Aviles, M. Vance, K. Fountain, and G. Sonnenfeld. 2002. Effects of the hindlimb-unloading model of spaceflight conditions on resistance of mice to infection with Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 110:262-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamini, Y., and Y. Hochberg. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate—a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57:289-300. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruce, R. J., C. M. Ott, V. M. Skuratov, and D. L. Pierson. 2005. Microbial surveillance of potable water sources of the International Space Station. SAE Trans. 114:283-292. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chemani, C., et al. 2009. Role of LecA and LecB lectins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced lung injury and effect of carbohydrate ligands. Infect. Immun. 77:2065-2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comolli, J. C., and T. J. Donohue. 2004. Differences in two Pseudomonas aeruginosa cbb3 cytochrome oxidases. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1193-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper, B., D. Eckert, N. L. Andon, J. R. Yates, and P. A. Haynes. 2003. Investigative proteomics: identification of an unknown plant virus from infected plants using mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 14:736-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crabbé, A., et al. 2008. Use of the rotating wall vessel technology to study the effect of shear stress on growth behaviour of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01. Environ. Microbiol. 10:2098-2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crabbé, A., et al. 2010. Response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 to low shear modelled microgravity involves AlgU regulation. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1545-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig, R., and R. C. Beavis. 2004. TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics 20:1466-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davey, M. E., N. C. Caiazza, and G. A. O'Toole. 2003. Rhamnolipid surfactant production affects biofilm architecture in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 185:1027-1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies, K. J., D. Lloyd, and L. Boddy. 1989. The effect of oxygen on denitrification in Paracoccus denitrificans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135:2445-2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding, Y., B. M. Davis, and M. K. Waldor. 2004. Hfq is essential for Vibrio cholerae virulence and downregulates sigma expression. Mol. Microbiol. 53:345-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eng, J. K., A. L. McCormack, and J. R. Yates III. 1994. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 5:976-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filiatrault, M. J., et al. 2005. Effect of anaerobiosis and nitrate on gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 73:3764-3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fury, W., F. Batliwalla, P. K. Gregersen, and W. Li. 2006. Overlapping probabilities of top ranking gene lists, hypergeometric distribution, and stringency of gene selection criterion. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 1:5531-5534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilboa-Garber, N. 1972. Purification and properties of hemagglutinin from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its reaction with human blood cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 273:165-173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilboa-Garber, N., L. Mizrahi, and N. Garber. 1977. Mannose-binding hemagglutinins in extracts of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can. J. Biochem. 55:975-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gueguinou, N., et al. 2009. Could spaceflight-associated immune system weakening preclude the expansion of human presence beyond Earth's orbit? J. Leukoc. Biol. 86:1027-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawkins, W. R., and J. F. Ziegelschmid. 1975. Clinical aspects of crew health. Biomedical results of Apollo. NASA Spec. Rep. 368:43-81. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanehisa, M., et al. 2008. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:D480-D484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur, I., E. R. Simons, V. A. Castro, C. M. Ott, and D. L. Pierson. 2005. Changes in monocyte functions of astronauts. Brain Behav. Immun. 19:547-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaur, I., E. R. Simons, A. S. Kapadia, C. M. Ott, and D. L. Pierson. 2008. Effect of spaceflight on ability of monocytes to respond to endotoxins of gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15:1523-1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerr, K. G., and A. M. Snelling. 2009. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a formidable and ever-present adversary. J. Hosp. Infect. 73:338-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lizewski, S. E., et al. 2004. Identification of AlgR-regulated genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by use of microarray analysis. J. Bacteriol. 186:5672-5684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynch, S. V., E. L. Brodie, and A. Matin. 2004. Role and regulation of sigma S in general resistance conferred by low-shear simulated microgravity in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:8207-8212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majdalani, N., C. K. Vanderpool, and S. Gottesman. 2005. Bacterial small RNA regulators. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40:93-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McClure, C. D., and N. L. Schiller. 1996. Inhibition of macrophage phagocytosis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa rhamnolipids in vitro and in vivo. Curr. Microbiol. 33:109-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nickerson, C. A., et al. 2000. Microgravity as a novel environmental signal affecting Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium virulence. Infect. Immun. 68:3147-3152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nickerson, C. A., et al. 2003. Low-shear modeled microgravity: a global environmental regulatory signal affecting bacterial gene expression, physiology, and pathogenesis. J. Microbiol. Methods 54:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novikova, N., et al. 2006. Survey of environmental biocontamination on board the International Space Station. Res. Microbiol. 157:5-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pamp, S. J., and T. Tolker-Nielsen. 2007. Multiple roles of biosurfactants in structural biofilm development by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 189:2531-2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qian, W. J., et al. 2005. Probability-based evaluation of peptide and protein identifications from tandem mass spectrometry and SEQUEST analysis: the human proteome. J. Proteome Res. 4:53-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schweizer, H. D. 1993. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. Biotechniques 15:831-834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sittka, A., V. Pfeiffer, K. Tedin, and J. Vogel. 2007. The RNA chaperone Hfq is essential for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 63:193-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sonnenfeld, G. 2005. The immune system in space, including Earth-based benefits of space-based research. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 6:343-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sonnleitner, E., et al. 2003. Reduced virulence of a hfq mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa O1. Microb. Pathog. 35:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sonnleitner, E., M. Schuster, T. Sorger-Domenigg, E. P. Greenberg, and U. Blasi. 2006. Hfq-dependent alterations of the transcriptome profile and effects on quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1542-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor, G. R. 1974. Recovery of medically important microorganisms from Apollo astronauts. Aerosp. Med. 45:824-828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valentin-Hansen, P., M. Eriksen, and C. Udesen. 2004. The bacterial Sm-like protein Hfq: a key player in RNA transactions. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1525-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams, P., and M. Camara. 2009. Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:182-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson, J. W., C. M. Ott, K. Honer zu Bentrup, et al. 2007. Space flight alters bacterial gene expression and virulence and reveals a role for global regulator Hfq. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:16299-16304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson, J. W., C. M. Ott, L. Quick, R. Davis, K. H. zu Bentrup, et al. 2008. Media ion composition controls regulatory and virulence response of Salmonella in spaceflight. PLoS One 3:e3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson, J. W., et al. 2002. Low-shear modeled microgravity alters the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium stress response in an RpoS-independent manner. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5408-5416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson, J. W., et al. 2002. Microarray analysis identifies Salmonella genes belonging to the low-shear modeled microgravity regulon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:13807-13812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winzer, K., et al. 2000. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa lectins PA-IL and PA-IIL are controlled by quorum sensing and by RpoS. J. Bacteriol. 182:6401-6411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]