Abstract

The GGDEF domain protein MxdA, which is important for biofilm formation in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1, was hypothesized to possess diguanylate cyclase activity. Here, we demonstrate that while MxdA controls the cellular level of c-di-GMP in S. oneidensis, it modulates the c-di-GMP pool indirectly.

Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 is a facultative gammaproteobacterium with extensive electron transfer pathways, which are important for both Fe mineral dissolution and bioremediation (7, 8, 22). Consequently, significant research has been conducted on its biofilms and the regulation thereof (20, 21). Biofilms of S. oneidensis MR-1 were postulated to be controlled by intracellular levels of the bacterial second messenger c-di-GMP (19), which is synthesized by diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and hydrolyzed by c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterases (PDEs) (2, 10, 17). Studies in other microorganisms have established that proteins containing GGDEF amino acid sequence motifs often possess DGC activity (9, 12, 14), while proteins containing EAL and HD-GYP motifs often possess PDE activity (3, 9, 11, 12, 13).

Previously, a ΔmxdA mutant was found to have a severe biofilm phenotype, as well as lower intracellular levels of c-di-GMP than the wild type (19). The biofilm phenotype could be complemented by heterologous expression of the diguanylate cyclase VCA0956 (19). The amino acid sequence of MxdA shows weak similarity to the GGDEF motif; however, the amino acid sequence NVDEF is found instead of the canonical GGDEF. Based on these observations, MxdA was hypothesized to possess DGC activity, which was experimentally examined here.

In order to directly test this hypothesis, we first attempted to demonstrate DGC activity of MxdA in vitro. Full-length, soluble His6-tagged mxdA (His6-mxdA), which phenotypically complemented the biofilm phenotype of a ΔmxdA mutant (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), was expressed in Escherichia coli DH5α-λpir and purified to >90% homogeneity using a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) affinity column and subsequently assayed for DGC activity as previously reported (9, 10). Purified VCA0956 served as a positive control (18). c-di-GMP was quantified by phosphorimaging with a detection limit of approximately 2 × 10−18 mol c-di-GMP. Using this in vitro assay, no DGC activity of purified MxdA was observed. To exclude that the absence of DGC activity could have been due to a loss of some activating factor during purification of His6-MxdA, we also directly assayed soluble cell extracts of E. coli expressing MxdA or VCA0956 and again found no evidence of DGC activity for His6-MxdA, while such activity was observed for the VCA0956-expressing E. coli (data not shown).

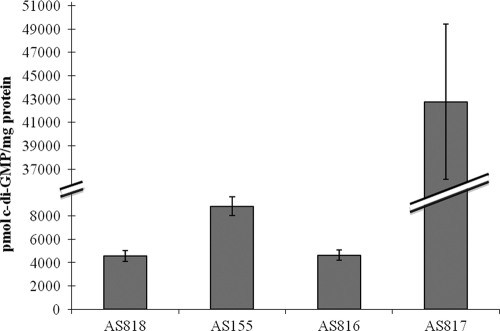

As this finding seemed to contradict the observation that overexpression of mxdA in a ΔmxdA strain resulted in an at least 2-fold-higher cellular c-di-GMP level (19), we considered whether the elevated c-di-GMP level of the mxdA-overexpressing strain was a consequence of a general stress associated with heterologous overexpression rather than specific to MxdA. This hypothesis was supported by a recent report on a link between cellular stress due to ribosome stalling and elevated c-di-GMP (1). To test whether the elevated c-di-GMP level could be caused by overexpression of any protein, we determined the intracellular c-di-GMP level of a ΔmxdA strain overexpressing gfp, using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS-MS) analysis as previously reported (19). While gfp expression was verified through Western blot analysis (data not shown), no elevated c-di-GMP level was found in this strain (Fig. 1), indicating that the elevated level of c-di-GMP in the mxdA-overexpressing strain was mxdA specific.

FIG. 1.

Cellular levels of c-di-GMP in S. oneidensis strains. The strains assayed included AS818 (AS140 pLacTac), AS155 [AS140 pLacTac-(his)6mxdA], AS816 [AS140 pLacTac-(his)6gfp], and AS817 (AS140 pLacTac-VCA0956). Error bars represent one standard deviation.

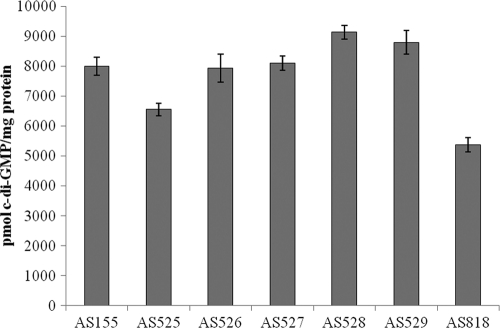

To exclude the possibility that some cellular factor necessary for MxdA activation in vivo was missing in the in vitro experiments, we examined the in vivo c-di-GMP levels of S. oneidensis strains expressing MxdA. Previous studies of characterized DGCs have shown that mutations of the canonical amino acid sequence GG(D/E)EF resulted in severely reduced or abolished DGC activity (3, 6). The GGDEF domain of MxdA contains, at an equivalent position, the sequence NVDEF. If MxdA possessed DGC activity, overexpression of an mxdA allele containing mutations in these residues should result in intracellular c-di-GMP levels different from those of strains overexpressing wild-type mxdA. We constructed five mxdA alleles in which the NVDEF amino acid sequence was converted to GGDEF, NGDEF, NADEF, GVDEF, and AVDEF. We overexpressed these alleles in the S. oneidensis ΔmxdA strain, verified expression via Western blotting (data not shown), and determined the intracellular c-di-GMP levels as described above. We found that mutation of these residues did not significantly affect intracellular c-di-GMP levels (Fig. 2). This finding strongly implied that MxdA also does not possess DGC activity in vivo.

FIG. 2.

Cellular levels of c-di-GMP in S. oneidensis strains expressing mutant mxdA alleles. The strains assayed included AS155 [AS140 pLacTac-(his)6mxdA], AS525 [AS140 pLacTac-(his)6mxdA NVDEF→GGDEF], AS526 [AS140 pLacTac-(his)6mxdA NVDEF→ NGDEF], AS527 [AS140 pLacTac-(his)6mxdA NVDEF→NADEF], AS528 [AS140 pLacTac-(his)6mxdA NVDEF→GVDEF], AS529 [AS140 pLacTac-(his)6mxdA NVDEF→AVDEF], and AS818 (AS140 pLacTac). Error bars represent one standard deviation.

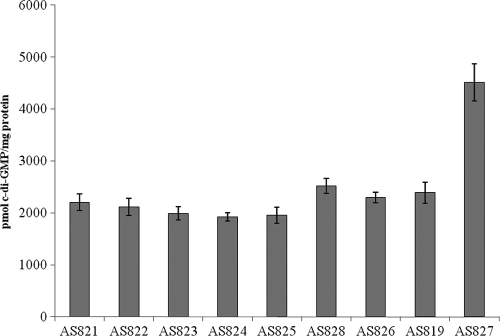

In order to test whether expression of MxdA in microorganisms other than S. oneidensis causes an increase in c-di-GMP, we also expressed the wild-type and mutated mxdA alleles in E. coli DH5α-λpir, verified expression via Western blotting (data not shown), and compared the intracellular c-di-GMP levels of these strains to those of strains expressing VCA0956 (a DGC). While the VCA0956-expressing strain contained an elevated c-di-GMP level, no alteration of the intracellular c-di-GMP level was found in mxdA-expressing E. coli relative to the empty-plasmid-carrying strain (Fig. 3). This implied that the elevated c-di-GMP level associated with mxdA overexpression was specific to S. oneidensis and is not a general mxdA characteristic.

FIG. 3.

Cellular levels of c-di-GMP in E. coli strains. The strains assayed included AS821 [DH5α-λpir pLacTac-(his)6mxdA NVDEF→GGDEF], AS822 [DH5α-λpir pLacTac-(his)6mxdA NVDEF→NGDEF], AS823 [DH5α-λpir pLacTac-(his)6mxdA NVDEF→NADEF], AS824 [DH5α-λpir pLacTac-(his)6mxdA NVDEF→GVDEF], AS825 [DH5α-λpir pLacTac-(his)6mxdA NVDEF→AVDEF], AS828 (DH5α-λpir pLacTac), AS826 [DH5α-λpir pLacTac-(his)6gfp], AS819 [DH5α-λpir pLacTac-(his)6mxdA], and AS827 (DH5α-λpir pLacTac-VCA0956). Error bars represent one standard deviation.

If the MxdA protein is not a DGC, by what indirect means does it control the cellular c-di-GMP level? A few proteins containing noncanonical GGDEF and EAL motifs have been characterized and may offer a clue to a potential mechanism of MxdA action. The GGDEF domain protein GdpS from Staphylococcus epidermis was found to enhance biofilm formation through means that did not involve c-di-GMP (5). Instead, it elevated expression of an exopolysaccharide biosynthesis operon, which in turn conferred the biofilm phenotype. The change in expression levels did not depend upon c-di-GMP biosynthesis; alleles of GdpS containing mutated GGDEF domains could still complement the deletion mutant (5). Likewise, in Salmonella enterica, the EAL domain protein STM1344 and the GGDEF-EAL domain protein CsrD operate via regulation of RNA transcript production and degradation by a mechanism shown to be independent of c-di-GMP (15, 16). In each of these cases, the proteins contain noncanonical amino acid sequences at corresponding positions in the protein, but no direct metabolic activity toward c-di-GMP was detected.

However, in all these cases, changing the intracellular c-di-GMP level by overexpression of a DGC or PDE was insufficient to complement the GGDEF or EAL domain protein deletion mutant (5, 15, 16). In contrast, the biofilm phenotype of the ΔmxdA mutant could be complemented by overexpression of VCA0956, and the biofilm phenotype of a ΔmxdA mutant was consistent with the biofilm defects observed in deletion mutants of other essential DGC genes in other microorganisms (4, 14, 19). This may indicate that the role of MxdA in biofilm formation has a connection with c-di-GMP metabolism but that it is indirect.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant MCB-0617952 and Department of Energy grant DE-FG02-07ER64386-A2 to A.M.S. and by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to S.R.

We thank Kai Thormann, Steffi Dutler, and Soni Shukla for strain construction.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 January 2011.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boehm, A., et al. 2009. Second messenger signalling governs Escherichia coli biofilm induction upon ribosomal stress. Mol. Microbiol. 72:1500-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang, A. L., et al. 2001. Phosphodiesterase A1, a regulator of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum, is a heme-based sensor. Biochemistry 40:3420-3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christen, M., B. Christen, M. Folcher, A. Schauerte, and U. Jenal. 2005. Identification and characterization of a cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase and its allosteric control by GTP. J. Biol. Chem. 280:30829-30837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia, B., et al. 2004. Role of the GGDEF protein family in Salmonella cellulose biosynthesis and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 54:264-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holland, L. M., et al. 2008. A staphylococcal GGDEF domain protein regulates biofilm formation independently of cyclic dimeric GMP. J. Bacteriol. 190:5178-5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malone, J. G., et al. 2007. The structure-function relationship of WspR, a Pseudomonas fluorescens response regulator with a GGDEF output domain. Microbiology 153:980-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers, C. R., and K. H. Nealson. 1988. Bacterial manganese reduction and growth with manganese oxide as the sole electron acceptor. Science 240:1319-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nealson, K. H., A. Belz, and B. McKee. 2002. Breathing metals as a way of life: geobiology in action. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 81:215-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul, R., et al. 2004. Cell cycle-dependent dynamic localization of a bacterial response regulator with a novel di-guanylate cyclase output domain. Genes Dev. 18:715-727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross, P., et al. 1987. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature 325:279-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan, R. P., et al. 2006. Cell-cell signaling in Xanthomonas campestris involves an HD-GYP domain protein that functions in cyclic di-GMP turnover. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:6712-6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Ryjenkov, D. A., M. Tarutina, O. V. Moskvin, and M. Gomelsky. 2005. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J. Bacteriol. 187:1792-1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt, A. J., D. A. Ryjenkov, and M. Gomelsky. 2005. The ubiquitous protein domain EAL is a cyclic diguanylate-specific phosphodiesterase: enzymatically active and inactive EAL domains. J. Bacteriol. 187:4774-4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simm, R., M. Morr, A. Kader, M. Nimtz, and U. Romling. 2004. GGDEF and EAL domains inversely regulate cyclic di-GMP levels and transition from sessility to motility. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1123-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simm, R., U. Remminghorst, I. Ahmad, K. Zakikhany, and U. Romling. 2009. A role for the EAL-like protein STM1344 in regulation of CsgD expression and motility in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 191:3928-3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki, K., P. Babitzke, S. R. Kushner, and T. Romeo. 2006. Identification of a novel regulatory protein (CsrD) that targets the global regulatory RNAs CsrB and CsrC for degradation by RNase E. Genes Dev. 20:2605-2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tal, R., et al. 1998. Three cdg operons control cellular turnover of cyclic di-GMP in Acetobacter xylinum: genetic organization and occurrence of conserved domains in isoenzymes. J. Bacteriol. 180:4416-4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamayo, R., A. D. Tischler, and A. Camilli. 2005. The EAL domain protein VieA is a cyclic diguanylate phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 280:33324-33330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thormann, K. M., et al. 2006. Control of formation and cellular detachment from Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 biofilms by cyclic di-GMP. J. Bacteriol. 188:2681-2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thormann, K. M., R. M. Saville, S. Shukla, D. A. Pelletier, and A. M. Spormann. 2004. Initial phases of biofilm formation in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. J. Bacteriol. 186:8096-8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thormann, K. M., R. M. Saville, S. Shukla, and A. M. Spormann. 2005. Induction of rapid detachment in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 187:1014-1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward, M. J., et al. 2004. A derivative of the menaquinone precursor 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoate is involved in the reductive transformation of carbon tetrachloride by aerobically grown Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 63:571-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.