Abstract

Details regarding the fate of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (basonym, Mycobacterium paratuberculosis) after manure application on grassland are unknown. To evaluate this, intact soil columns were collected in plastic pipes (lysimeters) and placed under controlled conditions to test the effect of a loamy or sandy soil composition and the amount of rainfall on the fate of M. paratuberculosis applied to the soil surface with manure slurry. The experiment was organized as a randomized design with two factors and three replicates. M. paratuberculosis-contaminated manure was spread on the top of the 90-cm soil columns. After weekly simulated rainfall applications, water drainage samples (leachates) were collected from the base of each lysimeter and cultured for M. paratuberculosis using Bactec MGIT ParaTB medium and supplements. Grass was harvested, quantified, and tested from each lysimeter soil surface. The identity of all probable M. paratuberculosis isolates was confirmed by PCR for IS900 and F57 genetic elements. There was a lag time of 2 months after each treatment before M. paratuberculosis was found in leachates. The greatest proportions of M. paratuberculosis-positive leachates were from sandy-soil lysimeters in the manure-treated group receiving the equivalent of 1,000 mm annual rainfall. Under the higher rainfall regimen (2,000 mm/year), M. paratuberculosis was detected more often from lysimeters with loamy soil than sandy soil. Among all lysimeters, M. paratuberculosis was detected more often in grass clippings than in lysimeter leachates. At the end of the trial, lysimeters were disassembled and soil cultured at different depths, and we found that M. paratuberculosis was recovered only from the uppermost levels of the soil columns in the treated group. Factors associated with M. paratuberculosis presence in leachates were soil type and soil pH (P < 0.05). For M. paratuberculosis presence in grass clippings, only manure application showed a significant association (P < 0.05). From these findings we conclude that this pathogen tends to move slowly through soils (faster through sandy soil) and tends to remain on grass and in the upper layers of pasture soil, representing a clear infection hazard for grazing livestock and a potential for the contamination of runoff after heavy rains.

Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (basonym, Mycobacterium paratuberculosis) is the causative agent of paratuberculosis (Johne's disease), a ruminant intestinal mycobacterial infection that causes cachexia and, in some species, diarrhea after a long preclinical phase. It is recognized as an ultimately fatal disease. The infection occurs worldwide as a production-limiting disease (16, 17, 18, 29). In addition, M. paratuberculosis is of interest because of its association with Crohn's disease in humans, although whether the association is causal is unknown and controversial (8, 10, 28, 35). By virtue of its inability to synthesize mycobactin, M. paratuberculosis is an obligate pathogen that is unable to replicate in the environment (19, 20). This characteristic in theory implies that it can be eradicated from a farm by removing all infected animals. However, the organism survives for long periods outside the host (21, 23, 53), a factor that must be considered in the design of paratuberculosis control programs.

The field application of manure has gained popularity in southern Chile. Under current legislation, bovine manure is considered an organic pasture fertilizer. While containing valuable nitrogen and potassium, livestock manure also may carry a variety of transmissible bacterial, viral, and protozoan pathogens (12, 26, 32), potential contaminants of surface and ground water. Regarding M. paratuberculosis persistence in farms environments, a study carried out in Minnesota dairy farms (36) showed a high correlation between the number of culture-positive environmental samples and the within-herd M. paratuberculosis infection prevalence. The organism was isolated from manure storage (68% of farms) and water runoff (6% of farms) samples. A Dutch study showed that sheep grazing on pastures previously fertilized with manure from M. paratuberculosis-infected cattle became infected with this pathogen (27).

Soil type influences microbial movement through soils (30, 38, 43). This is due partly to differences in absorptive properties of its colloidal materials. Organic matter and clay particles have the greatest effects on movement as a result of microbial absorption to negatively charged surfaces (26). It also has been shown that faster microbial movement occurs in coarse soil with large pore spaces than in finer-textured soils, where pore sizes are significantly smaller (3, 13, 31). The microbes' own surface properties also influence percolation through or attachment to soil particles (22), where the electrostatic forces of cell surface charge and hydrophobicity allow reversible attachment to soil particles (9).

The majority of studies investigating microbial movement in soil have been done using either intact soil or disturbed soil in lysimeters (open-ended vessels containing soil of known characteristics used to study aspects of the hydrological cycle, e.g., infiltration, runoff, evapotranspiration, and soluble constituents removed in drainage, etc.) (3, 13, 14, 25, 30). Intact soil core samples that maintained undisturbed soil and plant structures, texture, hydraulic conductivity, and porosity were more accurate in predicting pathogen movement under natural soil conditions (43, 49). Two recent studies investigated the passage of M. paratuberculosis through a saturated aquifer and the adsorption of the bacteria to soil particles (4, 6). In both studies, factors affecting organism movement and attachment were analyzed in columns containing specific soil types artificially composed in a lysimeter. To date, no research on M. paratuberculosis passage through soil following manure application to the surface of undisturbed grassy soils and the effect of rainfall has been published. Such information may help to improve paratuberculosis control programs and to assess infection transmission risks due to pasture fertilization with contaminated manure. The aim of this study was to evaluate the progress of M. paratuberculosis draining through two types of undisturbed soil columns under simulated field conditions after the application of M. paratuberculosis-contaminated manure, followed by two simulated rainfall protocols.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

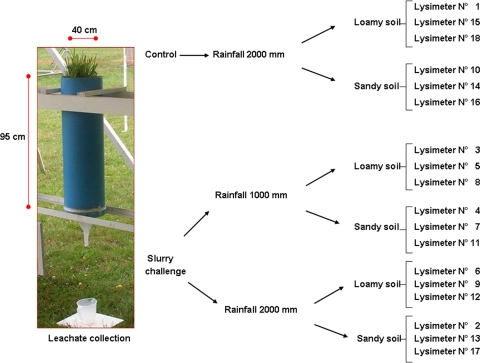

The effect of soil type and watering on M. paratuberculosis movement and survival in grassland soil and grasses was studied using monolith lysimeters treated with contaminated manure under controlled conditions at the National Institute for Agriculture Research, Osorno, Chile (40° 35′ S, 73° 08′ W, 73 m above sea level). Two soil types were evaluated, a volcanic ash soil of the Osorno soil series (Typic Hapludands) with loam texture (high levels of organic matter) and a sandy soil (low levels of organic matter). Intact core samples were collected from grasslands where no ruminant grazing had taken place for at least a year. The predominant grass species on the pastures were Holcus lanatus, Agrostis tenuis, and Lolium multiflorum. Soil samples were collected in 18 clean lysimeters (0.4-m internal diameter [0.5- by 1-m2 surface], 1.0-m PVC pipes) by manually driving the pipe into the soil and gently removing the pipe containing an undisturbed soil core sample with attendant surface plants (0.9 m soil depth). The bottom of each lysimeter was fitted with a funnel to facilitate the collection of drainage water (leachate). Between the bottom of the soil column and the funnel, a layer of washed sterile sand was used to remove particulates from the leachate (Fig. 1). Expandable foam was applied around the soil perimeter at the top of each lysimeter to prevent the direct flow of water down the sides of the PVC column. Leachate samples also were analyzed for nitrate and fecal coliforms (39). The lysimeters were kept in an open-air roofed shed to permit exposure to ambient temperatures while blocking rain.

FIG. 1.

Effects of manure, rainfall, and soil type on M. paratuberculosis detection: randomized block design with three replicates.

At the beginning of the experiment (spring treatment) and after 7 months (fall treatment), each of the 12 manure-treated lysimeters was inoculated with 500 ml (0.39 cm depth; 500 ml/1,256 cm2 soil surface) of fresh M. paratuberculosis-contaminated cow manure slurry, which was poured onto the lysimeter soil surface. This artificial slurry was created just minutes before application, using fresh feces collected from two previously culture-confirmed clinical cases of bovine paratuberculosis categorized as medium to heavy fecal shedders for both spring and fall application. To ensure sufficient numbers, the naturally contaminated fecal material also was spiked with culture-derived organisms to achieve an estimated final concentration of M. paratuberculosis of 108 CFU/ml slurry. For fecal material spiking, a Middlebrook broth culture of M. paratuberculosis ATCC 19698 in late-log-phase growth was used as described elsewhere (44). Fresh contaminated feces were mixed with distilled water at a 1:15 ratio to create a slurry consistency typical of manure applied to Chilean pastures (40).

Before manure treatment, the grass on the soil surface of each lysimeter was trimmed to a height of 5 cm. During the experimental period, the grass also was harvested when it reached 20 cm in height, on average. This protocol resulted in 14 cuttings during the 21-month period. At each cutting, the grass was weighed and then baked at 60°C for 48 h or until completely dry. Grass yield was expressed as total dry matter (DM) production.

The effect of high (2,000 mm) and low (1,000 mm) annual rainfall levels typical of southern Chile were evaluated. Distilled water was poured onto the soil surface of each lysimeter to simulate high or low rainfall at weekly intervals during a 21-month period, i.e., 19.6 and 39 mm of water per week for the low and high rainfall amounts, respectively. This simulated weekly rainfall began 1 week after the first slurry treatment and continued for the remainder of the study, skipping the week of the second manure treatment to avoid soil saturation. Water loss from columns due to evapotranspiration was estimated using an onsite automatic weather station. This quantity of water was added to the weekly rainfall amounts in an effort to hold constant the effective rainfall.

The effect of the two soil types and two simulated rainfall levels on M. paratuberculosis movement through the columns was evaluated according to a randomized treatment design using three replicates of each condition (Fig. 1). Lysimeters of both loamy and sandy soil types receiving high rainfall served as untreated controls (no slurry application). At the end of the experiment, soil samples for culture at different depths were carefully obtained (top soil, 0 to 5, 5 to 10, 10 to 15, 15 to 30, 30 to 60, and 60 to 90 cm). pH at the same levels was determined by laboratory methods as described elsewhere (39). In total, the study period covered 21 months.

Leachates were collected in sterile 500-ml polyethylene containers, and the volume was recorded. Leachate samples for M. paratuberculosis isolation were collected three times per week and held at room temperature. During the first half of the experiment, 2 weeks of samples (i.e., six samples) were pooled, processed, and inoculated into one medium tube for M. paratuberculosis culture. During the second half of the experiment, a month's worth of samples (n = 12) were pooled and inoculated into one medium tube. A total of 532 leachate cultures were set for M. paratuberculosis during the 21-month duration of the experiment.

Grass growing on the lysimeter soil surface was cut, and the clippings were processed for M. paratuberculosis detection since August 2008 (after the second slurry treatment). In total, grass was tested for M. paratuberculosis six times in a total of 108 cultures.

M. paratuberculosis detection.

Soil, grass, and leachate samples were processed per the manufacturer's protocol for bovine feces and inoculated into tubes of MGIT ParaTB medium (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) with supplement and antibiotics according to the manufacturer's protocol. Specifically, each tube contained 7 ml of modified Middlebrook 7H9 broth base with mycobactin J and a fluorescent oxygen indicator embedded in silicon at the bottom of the tube. To each tube was added 800 μl of MGIT ParaTB supplement (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD), 500 μl of egg yolk suspension (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD), and 100 μl of vancomycin (VAN) cocktail, resulting in final concentrations of 10 μg/ml vancomycin, 40 μg/ml amphotericin B, and 60 μg/ml nalidixic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) per the manufacturer's instructions. Each inoculated MGIT tube was entered into the MGIT 960 instrument and incubated at 37°C for 49 days. Tubes signaling positive by day 49 were removed and vortexed, and 500 μl was removed, freeze-dried, and submitted to the Bacteriology Department at the National Veterinary Institute, Uppsala, Sweden, for DNA extraction and real-time PCR analysis based on the IS900 and F57 genes, including an internal control for the indication of PCR inhibition (11).

DNA extraction method for bacterial growth in MGIT medium.

The freeze-dried MGIT culture medium was reconstituted with 500 μl of sterile purified water in the freeze-dried vials. The vials were inverted three times and briefly vortexed. The contents were aseptically transferred to 1.5-ml centrifuge tubes, which were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant of each tube was discarded, and the pellet was disrupted by pipetting with a mixture of 500 μl lysis buffer (2 mM EDTA, 400 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.6% SDS) and 2 μl proteinase K (10 μg/μl). This mixture then was transferred into a bead-beating tube (BioSpec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK) containing 200 μl of beads (0.1-mm zirconia/silica beads; BioSpec Products, Inc.). The tubes were incubated at 56°C for 2 h and shaken at 600 rpm. The tubes then were shaken in a cell disrupter (MiniBeadbeater-8; BioSpec Products) at 3,200 rpm for 60 s and then put on ice for 10 min, followed by the centrifugation of the tubes at 5,000 × g for 30 s. The entire liquid content from the bead-beating tube was transferred into 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes, and 500 μl of ethanol 100% was added. The tube was left to stand for 2 min and then was vortexed for 5 s and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 7 min. The resulting pellet was washed once in 200 μl 70% ethanol by resuspension and centrifugation in the same way as mentioned above and then was resuspended in 50 μl of sterile distilled water. The tube was placed in a dry heating block at 100°C for 5 min, after which it was centrifuged one last time (16,000 × g for 7 min), and the supernatant was harvested and stored as a template for real-time PCR.

Molecular confirmation.

The primers and probes used for primary detection for the real-time PCR were those of the previously described IS900 MP system (11), which includes the internal control plasmid pWIC9, which allows monitoring for PCR inhibition. The PCR mixture for each reaction was comprised of 8.625 μl of H2O, 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer II, 5.0 μl of MgCl (25 mM), 2.0 μl of GeneAmp deoxynucleoside triphosphate with dUTP (2.5 mM [each] dATP, dCTP, and dGTP and 5.0 mM dUTP), 0.75 μl of forward primer (10 μM), 0.75 μl of reverse primer (10 μM), 0.5 μl of M. paratuberculosis-specific probe (10 μM), 0.5 μl of mimic-specific probe (10 μM), 0.125 μl of AmpliTaq gold (5 U/μl), and 0.25 μl of AmpErase (uracil N-glycosylase; 1 U/μl). To this mixture, 2 μl of template DNA and 2 μl of internal control plasmid pWIC9 were added, for a total volume of 25 μl. The real-time PCR was performed on a Rotor-Gene 3000 with the following program: 45 cycles of 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 1 min. The results were analyzed with Rotor-Gene software version 5.0 and the built-in analytical tools dynamic tube normalization and slope correction. Real-time PCR curves of normalized fluorescence for 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) with a crossing threshold value of 0.01 at less than 40 cycles were considered positive, as long as the curves had a normal and expected shape. FAM-negative curves with a positive corresponding ROX curve (i.e., a positive mimic signal) were considered true negatives; otherwise, inhibition was suspected.

Molecular characterization of M. paratuberculosis DNA.

To discriminate M. paratuberculosis strains obtained from the manure-treated lysimeter group and those obtained from the control group, DNA extracts from a subset of M. paratuberculosis isolates, confirmed by IS900 and F57 real-time PCR, were subjected to mycobacterial interspersed repetitive-unit-variable-number tandem-repeat (MIRU-VNTR) typing. MIRU-VTNR typing was performed using five loci identified as polymorphic for M. paratuberculosis K10, and they were called MIRU-VNTR 292, X3, 25, 47, and 3 (from locus 1 to locus 5, respectively) as described previously (46). Primers designed to target flanking regions of the MIRU-VNTRs and the conditions of the PCR amplification were carried out as described previously (46). Briefly, the PCR mixture for each MIRU-VNTR locus contained 5 μl of template DNA; 1.5 mM magnesium chloride; 1 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (except for locus 2); 1 μM (each) primers; 50 μM (each) dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; and 1.25 U of platinum Taq (Invitrogen Ltd., Paisley, United Kingdom) in a final volume of 25 μl. Reactions were carried out using a GeneAmp 9600 PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR conditions were the following: 1 cycle of 5 min at 94°C; 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 58°C, and 30 s at 72°C; and 1 cycle of 7 min at 72°C. To detect differences in repeat numbers, the PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis using 1.5% agarose gels. Repeat numbers (alleles) were determined according to amplified fragment sizes using Gel Doc 2000 (Bio-Rad, Herefordshire, United Kingdom) and Quantity One 4.2.1 software (Bio-Rad) for fragment size calculation.

Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate associations between M. paratuberculosis detection in leachate water or grass clippings and slurry treatment, type of soil, rainfall regimen, and soil pH. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. The effect of soil type, rainfall, and slurry application on grass yield, expressed as total dry matter (DM) production, was evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the multiple-comparisons Tukey test. All of the analyses were performed using the Statistix 8.0 statistical package (Analytical Software, Tallahassee, FL).

RESULTS

Leachates were clear in color, indicating that water applied to the soil surface percolated through the soil and did not run down the sides of the lysimeters. Nitrate concentrations and fecal coliform counts in leachates were low during the first month and began increasing 30 days after slurry application (data not shown). This further verified that the slurry and water percolated through the soil instead of by-passing it.

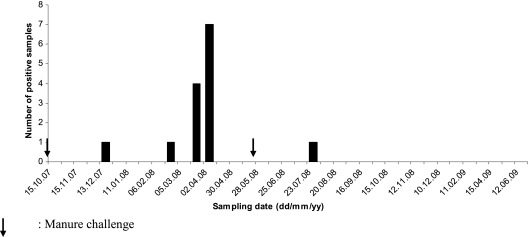

A greater number of lysimeter leachates were found positive for M. paratuberculosis from sandy (n = 4) than from loamy soil (n = 0) for the treated group receiving 1,000 mm annual rainfall (Table 1). Under the higher rainfall regime (2,000 mm/year), leachates from loamy soil (n = 3) had a slightly higher frequency of M. paratuberculosis detection than the sandy soil (n = 2). There was a lag time of 2 months after each manure treatment (October 2007, spring, and May 2008, fall) before M. paratuberculosis was found in leachates (Fig. 2). The highest detection rate was recorded 6 months after the first treatment. Only one leachate sample was positive 2 months after the fall slurry application. No positive samples were found during the last month of the experimental period. The proportion of M. paratuberculosis detection was higher in grass clippings than in lysimeter leachates (Table 1). Factors associated with M. paratuberculosis presence in lysimeter leachates were type of soil and soil pH (Tables 2 and 3). In the case of M. paratuberculosis presence on grass clippings, only slurry application showed significant association (Table 4).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive analysis of treatments on M. paratuberculosis detection both in lysimeter soil, leachate water, and grass clippingsa

| Lysimeter ID | Soil type | Manure presence | Rainfall regimen (mm) | M. paratuberculosis water leachate | No. of positive events | M. paratuberculosis water grass clippings | No. of positive events | M. paratuberculosis soil | pH | pH category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Loamy | No | 2,000 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 5.72 | Moderate acidic |

| 2 | Sandy | Yes | 2,000 | Pos | 1 | Pos | 1 | Neg | 6.16 | Slightly acidic |

| 3 | Loamy | Yes | 1,000 | Neg | 0 | Pos | 2 | Pos | 5.73 | Moderate acidic |

| 4 | Sandy | Yes | 1,000 | Pos | 2 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 6.23 | Slightly acidic |

| 5 | Loamy | Yes | 1,000 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 0 | Pos | 5.82 | Moderate acidic |

| 6 | Loamy | Yes | 2,000 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 5.91 | Moderate acidic |

| 7 | Sandy | Yes | 1,000 | Pos | 1 | Pos | 1 | Neg | 6.23 | Slightly acidic |

| 8 | Loamy | Yes | 1,000 | Neg | 0 | Pos | 1 | Neg | 5.80 | Moderate acidic |

| 9 | Loamy | Yes | 2,000 | Pos | 1 | Pos | 1 | Neg | 5.70 | Moderate acidic |

| 10 | Sandy | No | 2,000 | Pos | 1 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 6.15 | Slightly acidic |

| 11 | Sandy | Yes | 1,000 | Pos | 1 | Pos | 2 | Neg | 6.20 | Slightly acidic |

| 12 | Loamy | Yes | 2,000 | Pos | 2 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 5.77 | Moderate acidic |

| 13 | Sandy | Yes | 2,000 | Neg | 0 | Pos | 2 | Neg | 6.13 | Slightly acidic |

| 14 | Sandy | No | 2,000 | Pos | 1 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 5.98 | Moderate acidic |

| 15 | Loamy | No | 2,000 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 5.78 | Moderate acidic |

| 16 | Sandy | No | 2,000 | Pos | 1 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 6.02 | Slightly acidic |

| 17 | Sandy | Yes | 2,000 | Pos | 1 | Pos | 1 | Pos | 6.06 | Slightly acidic |

| 18 | Loamy | No | 2,000 | Pos | 1 | Neg | 0 | Neg | 5.83 | Moderate acidic |

| Total | 20/532 leachates sampled | 11/108 grass clippings sampled |

Neg, negative; Pos, positive.

FIG. 2.

Frequency and temporal distribution of M. paratuberculosis-positive lysimeter leachate samples during the study period.

TABLE 2.

M. paratuberculosis detection in lysimeter leachate samples by soil typea

| Soil type |

M. paratuberculosis |

|

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |

| Loamy | 4 | 6 |

| Sandy | 9 | 1 |

P < 0.05 (one tailed).

TABLE 3.

M. paratuberculosis detection in lysimeter leachate samples by soil pHa

| pH |

M. paratuberculosis |

|

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |

| Moderate acidic | 5 | 6 |

| Slightly acidic | 8 | 1 |

P < 0.05 (one tailed).

TABLE 4.

M. paratuberculosis detection in grass clippings by manure application treatment groupa

| Manure treatment |

M. paratuberculosis |

|

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |

| Application | 11 | 4 |

| No application | 0 | 6 |

P < 0.05 (two tailed).

From 18 lysimeters and 7 different soil depths evaluated at the conclusion of the trial, M. paratuberculosis was cultured from only three lysimeter soil samples. All three were from the uppermost levels of the soil columns of the manure-treated group (lysimeter 3, 5 to 10 cm; lysimeter 5, top soil; lysimeter 17, 0 to 5 cm). M. paratuberculosis was detected in leachates from control lysimeters, although M. paratuberculosis was detected more often from the manure-treated lysimeters than the controls.

No interaction was observed between soil type or manure slurry application on grass DM yield. The loamy soil yielded 2.1 times more grass dry matter than sandy soil, 217.8 ± 17.5 g DM/lysimeter compared to 101.5 ± 8.8 g DM/lysimeter, respectively (P < 0.0001). The manure slurry application did not increase pasture grass yield, with 130.2 ± 29.6 and 174.4 ± 20.3 g DM/lysimeter for control and slurry-treated lysimeters, respectively. This probably was due to the low concentration of available nutrients in diluted feces. Rainfall also did not affect grass yield. The overall production was 130.2 ± 29.6, 176.8 ± 34.5, and 171.9 ± 24.8 g DM/lysimeter for the control, low-, and high-rainfall treatments, respectively (P > 0.05). If analyzed on a per-hectare basis, grass yields varied between 8 and 17 g DM/ha, which is considered adequate to high for permanent pastures in southern Chile. The average grass growth rate was 0.28 g DM/lysimeter/day, between 0.02 g DM/lysimeter/day (winter period) and 1.59 g DM/lysimeter/day (spring time). Higher growth rates were found on loamy soil than on sandy soil, 30 ± 2.4 and 14 ± 1.2 kg DM/ha/d, on average, for the loamy and sandy soil, respectively (P < 0.001). Rainfall did not affect the grass growth rate, being, on average, 18 ± 4.4, 24 ± 4.4, and 24 ± 3.2 kg DM/ha/d for the control, low-, and high-rainfall treatments, respectively (P > 0.05).

The interpretation of MIRU-VNTR results on recovered M. paratuberculosis isolates was complicated for some loci by the presence of nonspecific bands. This was likely because of the presence of DNA from other organisms in the liquid cultures, which interfered with primers originally designed for typing M. paratuberculosis isolates. Reliable results for loci 1 and 4 in six cultures (four inoculated lysimeters and two control lysimeters) were obtained. All of the isolates tested from treated lysimeters showed four repeats for TR 292 (locus 1) and three repeats for TR 47 (locus 4), while all strains recovered from control lysimeters showed 3 and 2 repeats, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The present study represents the first attempt to detail the progress of M. paratuberculosis through soil after dairy cattle manure slurry application to grassland pastures under field conditions. The 2-month lag time before the first detection of M. paratuberculosis in leachates indicates a much slower movement of the organism through soil than has been described for Escherichia coli and Salmonella (42, 52). The latter organisms were found in leachates from similar soil columns within days after surface application.

In the present study, M. paratuberculosis detection in leachates occurred more frequently after slurry application in spring (October; 12/13 detection events) than in fall (May; only 1 detection event). We speculate that freeze-thaw cycles (5) decreased M. paratuberculosis longevity, as has been suggested by others (52). The higher M. paratuberculosis detection frequency in grass clippings than in lysimeter leachates, together with the long time interval before detection in leachates, suggests that M. paratuberculosis movement through soil is very slow, and that there is a bacterial preference to remain on grass and in the uppermost soil layers.

In the present study, there was no significant association in M. paratuberculosis detection between columns treated with M. paratuberculosis-containing slurry and control lysimeters with the same high rainfall regime (2,000 mm/year). Although the original soil used to prepare the undisturbed soil columns was warranted to have been free of livestock for more than a year, there was an unexpected result of four lysimeters showing at least one M. paratuberculosis culture-positive leachate. The most plausible explanation is that the soil was contaminated more than a year ago, i.e., before soil harvesting for the present lysimeter study. M. paratuberculosis is known to remain in soil for more than a year (23), a finding that has been confirmed recently (34, 55). Survival for up to 55 weeks was observed in a dry, fully shaded environment, with much shorter survival times in unshaded locations. UV radiation was not considered to be a factor, but diurnal temperature fluctuations correlated with a lack of shade were speculated to have reduced M. paratuberculosis viability. The organism survived for up to 24 weeks on grass that germinated through infected fecal material applied to the soil surface in completely shaded boxes and for up to 9 weeks on grass in 70% shade (54). Supporting this explanation, the genotyping of M. paratuberculosis strains recovered from control and treated lysimeters showed the strains to be distinctly different, thus ruling out the possibility of cross-contamination. M. paratuberculosis is an auxotroph incapable of producing mycobactin, and thus it is traditionally considered unable to replicate in the environment, making it an obligate pathogen (47). There is evidence that this is not always so and that M. paratuberculosis can grow in some media without mycobactin (1). If the organism can in fact replicate in an ecological niche in soil or water, this also could explain the detection of the organism in control lysimeters.

Variables such as soil type, amount of rainfall, and soil pH seem to play important roles in determining the fate of M. paratuberculosis under field conditions. It has been reported that soil type is a major factor influencing microbial passage in soils (30, 43). In the present study, a significant association between M. paratuberculosis recovery from leachates and sandy soil was shown; 9 of 13 M. paratuberculosis recoveries were from sandy soil lysimeters, which is consistent with what has been described for M. paratuberculosis under laboratory conditions (6). These results are not surprising, since it has been shown that greater microbial movement occurs in coarser soils with large pore spaces than in finer-textured soils, where pore sizes are significantly smaller (3, 13, 31). A study (15) showed that filtration significantly contributes to bacterial removal from leachates, where the average bacterial cell size was greater than the size of at least 5% of the particles. Pore size may contribute to filtration removal, the sedimentation of bacteria in pores, and the consequent reduction of soil permeability (33).

Not only do soil texture and particle size distribution affect the influence of filtration processes on bacterial movement but bacteria also more readily adsorb to positively charged mineral surfaces than to negatively charged mineral surfaces (41). A recent study (4) demonstrated that M. paratuberculosis has negatively charged, hydrophobic walls, and that its transport through positively charged soil particles is slow. A low degree of M. paratuberculosis recovery in loamy (volcanic ash) soil has been explained by a high adsorption rate due to electrostatic and van der Waal's forces and by cell surface hydrophobicity (6). These forces increase at acidic pHs and at a high electrolyte concentrations (24, 45). In this regard, the present study showed a strong association between M. paratuberculosis recovery from leachates at a slightly more than moderately acidic pH (Table 3). These results are consistent with those observed elsewhere (6) and follow the Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek (DLVO) theory of colloidal stability (7), where as ionic strength increases the thickness of the electrical double layer around the surface of both the bacteria and the soil particles decreases, leading to a decrease in the magnitude of the repulsive forces between the negatively charged bacteria and the sand grains. This allows attractive van der Waal's forces to overcome electrostatic repulsion, leading to an increased M. paratuberculosis attachment to soil particles. What is remarkable is that this theory of M. paratuberculosis transport through saturated aquifer soil has been experimentally demonstrated (6). In the present study it also has been confirmed under field conditions. In this regard, the results of our experimental field study suggest that volcanic ash soil rich in clay and with a more loamy texture represents an appropriate environment for M. paratuberculosis to be adsorbed. Organic matter and clay particles have the greatest effects on microbial movement as a result of their adsorption to negatively charged surfaces (26).

Mycobacterium paratuberculosis recovery in these lysimeter leachates was not significantly affected by the quantity of simulated rainfall. However, there was a trend suggesting that the 2,000-mm annual rainfall regimen cause higher M. paratuberculosis recovery (9 of 13 events) due to the so-called piston effect (2). Water flow rate, as governed by the rainfall intensity, affects the rate and extent of microbial translocation, with faster flow rates increasing bacterial movement (14, 38, 48). Higher concentrations of total coliforms, fecal coliforms, and fecal streptococci were found in drainage waters from fields after manure application following periods of heavy rainfall (31). Similar results have been reported for E. coli (50, 51).

Soil water composition affects not only microbial movement but also the survival of microorganisms in soil, with considerable interspecies variation in the ability to withstand both high and low water content. Studies of both bacteria and viruses indicate increasing movement in saturated soils. In addition, percolating water, in the form of irrigation or rainfall, will affect translocation through the soil matrix (26). Finally, a biological factor also seems to control bacterial movement through soil. Organisms possessing their own means of locomotion are able to move easily in a water-saturated soil, which has been shown to be of significant importance for motile E. coli strains (37), although this is not the case for M. paratuberculosis.

Significant associations between M. paratuberculosis in grass clippings and slurry application were observed. This suggests that a large portion of M. paratuberculosis remains on the grass and soil surface. This was supported by the finding that only 3 out of 126 subsurface soil cultures were positive for M. paratuberculosis at the conclusion of the study. Published information has shown an apparent 90 to 99% reduction in the viable M. paratuberculosis counts when contaminated feces was mixed with soil (53). This was probably due to the binding of the organism to soil particles, which are excluded from culture by sedimentation during sample preparation (53). The culture method used, in particular the use of antibiotics in the culture medium and disinfectants during sample preparation, further reduces the analytical sensitivity of in vitro culture by killing or inhibiting more than 2 log10 M. paratuberculosis cells (37). Thus, M. paratuberculosis viable counts and survival duration based on culture from soil are likely to be underestimated (54).

Although the overall M. paratuberculosis detection rate was low, the organism was recovered from soil, leachates, and grass clippings. These data are consistent with the prolonged environmental persistence of this pathogen and an apparent preference to stay on the soil surface or vegetation. It could be hypothesized that M. paratuberculosis is adsorbed to soil particles and possibly adversely affected by a more acidic soil pH.

Conclusions.

This is the first study on the fate of M. paratuberculosis in soil after dairy slurry application under field conditions. The bacterium tends to move slowly through soils, faster through sandy than loamy soil. The organism tends to remain on grass and in the upper layers of pasture soil, representing a clear hazard to grazing livestock for infection transmission and a potential to contaminate pasture rainwater runoff.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by FONDECYT/Chile project no. 1070239; Postgraduate School, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Universidad Austral de Chile; The National Veterinary Institute (SVA), Uppsala, Sweden; and Instituto Vasco de Investigación y Deasarrollo Agrario (NEIKER), Derio, Spain.

We thank Ruben Pulido, Zohre Ghotbi, and Becky Manning for valuable help.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adúriz, J. J., R. A. Juste, and N. Cortabarria. 1995. Lack of mycobactin dependence of mycobacteria isolated on Middlebrook 7H11 from clinical cases of ovine paratuberculosis. Vet. Microbiol. 45:211-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfaro, M., F. Salazar, S. Iraira, N. Teuber, and L. Ramirez. 2008. Dynamics of nitrogen and phosphorus losses in a volcanic soil of southern Chile. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 8:200-201. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bitton, G., N. Lahav, and Y. Henis. 1974. Movement and retention of Klebsiella aerogenes in soil columns. Plant Soil. 40:373-380. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolster, C. H., K. L. Cook, B. Z. Haznedaroglu, and S. L. Walker. 2009. The transport of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis through saturated aquifer materials. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 48:307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celis, S. 1988. Estadística agrometeorológica estación experimental remehue. Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias Estación Experimental Remehue. Ser. Remehue 6:27-31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhand, N. K., J.-A. L. L. M. Toribio, and R. J. Whittington. 2009. Adsorption of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis to soil particles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:5581-5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elimelech, M., J. Gregory, X. Jia, and R. A. Williams. 1995. Particle deposition and aggregation: measurement, modeling and simulation. Butterworth-Heinemann, Woburn, MA.

- 8.Feller, M., et al. 2007. Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis and Crohn's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 7:607-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginn, T. R., et al. 2002. Processes in microbial transport in the natural subsurface. Adv. Water Resources 25:1017-1042. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant, I. R. 2005. Zoonotic potential of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis: the current position. J. Appl. Microbiol. 98:1282-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herthnek, D., and G. Bölske. 2006. New PCR systems to confirm real-time PCR detection of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. BMC Microbiol. 6:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hooda, P. S., A. C. Edwards, H. A. Anderson, and A. Miller. 2000. A review of water quality concerns in livestock farming areas. Sci. Total Environ. 250:143-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huysman, F., and W. Verstraete. 1993. Water facilitated transport of bacteria in unsaturated soil columns: influence of cell surface hydrophobicity and soil properties. Soil Biol. Biochem. 25:83-90. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huysman, F., and W. Verstraete. 1993. Water facilitated transport of bacteria in unsaturated soil columns: influence of inoculation and irrigation methods. Soil Biol. Biochem. 25:91-97. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang, L. K., P. W. Chang, J. Findley, and T. F. Yen. 1983. Selection of bacteria with favorable transport properties through porous rock for the application of microbial enhanced oil recovery. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 46:1066-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson-Ifearulundu, Y. J., and J. B. Kaneene. 1998. Management-related risk factors for M. paratuberculosis infection in Michigan, U. S. A., dairy herds. Prev. Vet. Med. 37:41-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson-Ifearulundu, Y., and J. B. Kaneene. 1999. Distribution and environmental risk factors for paratuberculosis in dairy cattle herds in Michigan. Am. J. Vet. Res. 60:589-596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy, D. J., and G. Benedictus. 2001. Control of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection in agricultural species. Rev. Sci. Tech. 20:151-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambrecht, R. S., and M. T. Collins. 1993. Inability to detect mycobactin in Mycobacteria-infected tissues suggests an alternative iron acquisition mechanism by Mycobacteria in vivo. Microb. Pathog. 14:229-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambrecht, R. S., and M. T. Collins. 1992. Mycobacterium paratuberculosis factors that influence Mycobactin dependence. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 15:239-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsen, A. B., R. S. Merkal, and T. H. Vardaman. 1956. Survival time of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 17:549-551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindqvist, R., and G. Bengtsson. 1991. Dispersal dynamics in groundwater bacteria. Microb. Ecol. 21:49-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovell, R., M. Levi, and J. Francis. 1944. Studies on the survival of Johne's bacilli. J. Comp. Pathol. 54:120-129. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lytle, D., C. Frietch, and T. Covert. 2004. Electrophoretic mobility of Mycobacterium avium complex organisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5667-5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mawdsley, J. L., A. E. Brooks, R. J. Merry, and B. F. Pain. 1996. Use of novel soil tilting apparatus to demonstrate the horizontal and vertical movement of the protozoan pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum in soil. Biol. Fert. Soil. 23:215-220. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mawdsley, J., R. Bardgett, R. Merry, B. Pain, and M. Theodorou. 1995. Pathogens in livestock waste, their potential for movement through soil and environmental pollution. App. Soil Ecol. 2:1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muskens, J., D. Bakker, J. de Boer, and L. van Keulen. 2001. Paratuberculosis in sheep: its possible role in the epidemiology of paratuberculosis in cattle. Vet. Microb. 78:101-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naser, S. A., M. T. Collins, J. T. Crawford, and J. F. Valentine. 2009. Culture of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) from the blood of patients with Crohn's disease: a follow-up blind multi-center investigation. Open Inflamm. J. 2:22-23. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ott, S. L., S. J. Wells, and B. A. Wagner. 1999. Herd-level economic losses associated with Johne's disease on U.S. dairy operations. Prev. Vet. Med. 40:179-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paterson, E., et al. 1993. Leaching of genetically-modified Pseudomonas fluorescens through intact soil microcosms-influence of soil type. Biol. Fert. Soil. 15:308-314. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patni, N. K., R. Toxopeus, A. D. Tennant, and F. R. Hore. 1984. Bacterial quality of tile drainage water from manured and fertilized cropland. Water Res. 18:127-132. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pell, A. 1997. Manure and microbes: public and animal health problem? J. Dairy Sci. 80:2673-2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson, T. C., and R. C. Ward. 1989. Development of a bacterial transport model for coarse soils. Water Resources Bull. 25:349-357. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pickup, R. W., et al. 2005. Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in the catchment area and water of the River Taff in South Wales, United Kingdom, and its potential relationship to clustering of Crohn's disease cases in the city of Cardiff. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2130-2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierce, E. S. 2009. Possible transmission of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis through potable water: lessons from an urban cluster of Crohn's disease. Gut Pathog. 1:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raizman, E. A., et al. 2004. The distribution of Mycobacterium avium spp. paratuberculosis in the environment surrounding Minnesota dairy farms J. Dairy Sci. 87:2959-2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddacliff, L. A., A. Vadali, and R. J. Whittington. 2003. The effect of decontamination protocols on the numbers of sheep strain Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis isolated from tissues and faeces. Vet. Microbiol. 95:271-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds, P. J., P. Sharma, G. E. Jenneman, and M. J. McInerney. 1989. Mechanisms of microbial movement in subsurface materials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:2280-2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sadzawka, A., et al. 2006. Métodos de análisis de suelos recomendados para los suelos de Chile. Revisión 2006. Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias, Santiago, Chile.

- 40.Salazar, F., J. Dummont, D. Chadwick, R. Saldaña, and M. Santana. 2007. Characterization of dairy slurry in Southern Chile farms. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 67:155-162. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scholl, M. A., A. L. Mills, J. S. Herman, and G. M. Hornberger. 1990. The influence of mineralogy and solution chemistry on the attachment of bacteria to representative aquifer minerals. J. Contam. Hydrol. 6:321-336. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Semenov, A. V., L. van Overbeek, and A. H. C. van Bruggen. 2009. Percolation and survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium in soil amended with contaminated dairy manure or slurry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:3206-3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith, M. S., G. W. Thomas, R. E. White, and D. Ritonga. 1985. Transport of Escherichia coli through intact and disturbed soil columns. J. Environ. Qual. 14:87-91. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sung, J. S., H. H. Jun, E. J. B. Manning, and M. T. Collins. 2007. Rapid and reliable method for quantification of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis by use of the Bactec MGIT 960 system J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1941-1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor, D. H., R. S. Moore, and L. S. Sturman. 1981. Influence of pH and electrolyte composition on adsorption of poliovirus by soils and minerals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 42:976-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thibault, V. C., et al. 2007. New variable-number tandem-repeat markers for typing Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis and M. avium strains: comparison with IS900 and IS1245 restriction fragment length polymorphism typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:2404-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thorel, M. F., M. Krichevsky, and V. V. Levy-Frebault. 1990. Numerical taxonomy of mycobactin-dependent mycobacteria, emended description of Mycobacterium avium, and description of Mycobacterium avium subsp. avium subsp. nov., Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis subsp. nov., and Mycobacterium avium subsp. silvaticum subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 40:254-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trevors, J. T., J. D. van Elsas, L. S. van Oberbeek, and M. E. Starodub. 1990. Transport of a genetically engineered Pseudomonas fluorescens strain through a soil microcosm. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:401-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Elsas, J. D., J. D. Trevors, and L. S. van Overbeek. 1991. Influence of soil properties on the vertical movement of genetically marked Pseudomonas fluorecens through large soil microcosms. Biol. Fert. Soil. 10:249-255. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vinten, A. J. A., et al. 2002. Fate of Escherichia coli O157 in soil and drainage water following cattle slurry application at 3 sites in southern Scotland. Soil Use Manage. 18:223-231. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vinten, A. J. A., J. T. Douglas, M. N. Aitken, and D. R. Fenlon. 2004. Relative risk of surface water pollution by E. coli derived from faeces of grazing animals compared to slurry application. Soil Use Manage. 20:13-22. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Warnemuende, E. A., and R. S. Kanwar. 2002. Effects of swine manure application on bacterial quality of leachate from intact soil columns. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 45:1849-1857. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whittington, R. J., et al. 2003. Isolation of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis from environmental samples collected from farms before and after destocking sheep with paratuberculosis. Aust. Vet. J. 81:559-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whittington, R. J., D. J. Marshall, P. J. Nicholls, I. B. Marsh, and L. A. Reddacliff. 2004. Survival and dormancy of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in the environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2989-3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whittington, R. J., I. B. Marsh, and L. A. Reddacliff. 2005. Survival of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in dam water and sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5304-5308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]