Abstract

Two serotype 19A (ST695) Streptococcus pneumoniae vaccine escape recombinant strains attributable to capsular switching events were detected by a laboratory surveillance system that is an integral part of a vaccination program begun in Liguria, Italy, in May 2003, an Italian administrative region with long-lasting high coverage, an unusual occurrence in Europe. To our knowledge, this is the first detection of an occurrence of capsular switching outside the United States.

The 7-valent conjugated vaccine (PCV7) was introduced in the United States in 2000, and the rapid implementation of coverage in children has resulted in a dramatic decrease in the incidence of invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal disease (IPD and non-IPD, respectively) (11).

The immune response elicited by PCV7 also has an important effect on asymptomatic carriers, and hence it eradicates colonizing pneumococci of vaccine serotypes, creating a precondition for an increase in the role of nonvaccine serotypes (2, 8, 9, 12).

Surveillance in the United States showed that the emergence of nonvaccine serotypes was due mainly to the expansion of preexisting clones circulating before vaccine implementation. The main exception is the appearance of a novel serotype 19A vaccine escape recombinant strain (3). This strain has a genotype previously associated only with vaccine serotype 4 and expresses a nonvaccine serotype 19A capsule. The main recombinational event, involving capsular locus flanking regions and two adjacent penicillin-binding proteins, has occurred since 2003, resulting in recombination between the recipient ST695, serotype 4, and a donor ST199, serotype 19A. In 2005, two new genotypes of serotype 19A vaccine escape strains emerged: ST2365 type 19A and ST899 type 19A, both derived from two new recombinational events between serotype 4 recipients and serotype 19A donors (3).

PCV7 was officially licensed in Europe in 2001, but Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom have included it in their national immunization programs only since 2006. European data regarding pneumococcal epidemiological changes after PCV7 implementation are limited because of the relatively recent introduction of the vaccine and the difficulty to rapidly reach high vaccine coverage.

In May 2003, a large-scale program of vaccination was started in Liguria, Italy. Liguria has a population of 1,572,000 inhabitants, and every 1-year birth cohort includes about 12,000 newborns. All newborns were invited to receive PCV7 according to a vaccination schedule at 3, 5, and 11 months of age. PCV7 uptake began to increase after May 2003, reaching a coverage of >80% and >90% in every district since 2004 and 2007, respectively, determining an epidemiological situation that occurs quite infrequently in Europe (1).

At the end of 2006, a mixed active-passive laboratory surveillance system for the detection and characterization of noninvasive and invasive strains in children and adults was implemented in support of the universal vaccination program.

Pneumococcal detection and serotype determination were performed using real-time PCR, the Quellung reaction, and primer-specific PCR (4, 10). Molecular characterization of selected isolates was performed by multilocus sequence typing (MLST), and sequence analysis of the capsular locus flanking regions of potentially recombinant strains was carried out (3, 6).

After PCV7 implementation, a clear reduction in the role of vaccine serotypes in causing IPD and non-IPD was observed in parallel with an increase in the incidence of nonvaccine serotypes. In particular, the proportions of IPD and non-IPD cases due to serotype 19A increased from 7 and 13%, respectively, for the period 2006 to 2008 to 11 and 19%, respectively, for the period 2009 to 2010. The implementation of 13-valent conjugate vaccine, begun in Liguria in July 2010, will extend the coverage against serotype 19A disease.

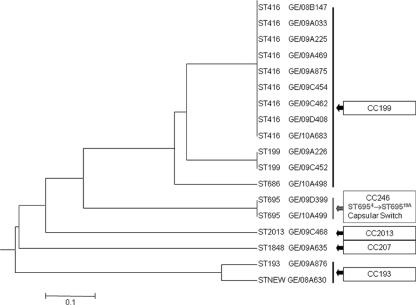

Eighteen serotype 19A strains collected between 2008 and 2010 were genotyped: they belonged to 8 different sequence types (STs), including 1 new genotype (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

UPMGA (unweighted-pair group method using average linkages) tree generated from MLST allelic profiles for 18 invasive and noninvasive serotype 19A S. pneumoniae isolates. The scale bar indicates the genetic linkage distance. CC, clonal complex.

Genotypic characterization showed that most of the serotype 19A disease can be explained by clonal expansion of two STs, ST416 and ST199, belonging to the same clonal complex, 199, which circulated in Italy before vaccination was implemented (7) (Table 1). Of great interest is the detection in December 2009 and March 2010 of two vaccine escape recombinant strains belonging to serotype 19A (ST695). The two strains were isolated from two pediatric patients with acute otitis media; there is no epidemiological link between the two cases. One child, who was 4 months old, received only one dose of PCV7, and the other, who was 4 years old, completed the vaccination course.

TABLE 1.

Allelic profile (MLST) and antibiotype for 18 selected invasive and noninvasive serotype 19A S. pneumoniae isolatesa

| Isolate | Yr of collection | ST | MLST allelic profilec |

Diagnosis | Age | MIC (μg/ml)b |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aroE | gdh | gki | recP | spi | xpt | ddl | PEN | ERY | |||||

| GE/08B147 | 2008 | 416 | 1 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 17 | 51 | 14 | Otitis media | 2 yr | 0.012 | 0.032 |

| GE/09A033 | 2009 | 416 | 1 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 17 | 51 | 14 | Mastoiditis | 1 yr | 0.012 | 0.047 |

| GE/09A225 | 2009 | 416 | 1 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 17 | 51 | 14 | Otitis media | 2 yr | 0.016 | 0.064 |

| GE/09A469 | 2009 | 416 | 1 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 17 | 51 | 14 | Meningitis | 71 yr | 0.012 | >4 |

| GE/09A875 | 2009 | 416 | 1 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 17 | 51 | 14 | Otitis media | 2 yr | 0.016 | 0.047 |

| GE/09C454 | 2009 | 416 | 1 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 17 | 51 | 14 | Otitis media | 7 mo | 0.016 | 0.047 |

| GE/09C462 | 2009 | 416 | 1 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 17 | 51 | 14 | Otitis media | 6 yr | 0.016 | 0.047 |

| GE/09D408 | 2009 | 416 | 1 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 17 | 51 | 14 | Otitis media | 7 mo | 0.012 | 0.023 |

| GE/10A683 | 2010 | 416 | 1 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 17 | 51 | 14 | Otitis media | 2 yr | 0.016 | 0.064 |

| GE/09A226 | 2009 | 199 | 8 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 17 | 4 | 14 | Otitis media | 2 yr | 0.032 | 0.032 |

| GE/09C452 | 2009 | 199 | 8 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 17 | 4 | 14 | Otitis media | 5 yr | 0.012 | 0.023 |

| GE/09C468 | 2009 | 2013 | 12 | 19 | 36 | 17 | 6 | 5 | 14 | Pneumonia | 2 yr | 0.032 | 0.023 |

| GE/10A498 | 2010 | 686 | 1 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 6 | 51 | 1 | Otitis media | 3 yr | 0.016 | 0.064 |

| GE/09A876 | 2009 | 193 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 16 | 1 | 26 | 1 | Otitis media | 4 yr | 0.016 | >4 |

| GE/08A630 | 2008 | New | 8 | 10 | 2 | 16 | 1 | 26 | 15 | Bacteremia | 81 yr | 0.012 | 0.023 |

| GE/09A635 | 2009 | 1848 | 10 | 8 | 30 | 35 | 6 | 1 | 9 | Pneumonia | 2 yr | >8 | >4 |

| GE/09D399 | 2009 | 695 | 16 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 113 | 18 | Otitis media | 4 mo | 0.012 | 0.094 |

| GE/10A499 | 2010 | 695 | 16 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 113 | 18 | Otitis media | 4 yr | 0.016 | 0.064 |

The isolates were collected between December 2008 and March 2010.

PEN, penicillin; ERY, erythromycin.

Each value represents a specific allele number obtained from gene sequence analysis.

The two recombinants strains belonged to P1 progeny previously identified as the major group of vaccine escape strains circulating in United States.

For all serotype 19A strains, susceptibility to penicillin and erythromycin was assayed by Etest and interpreted using the breakpoints suggested by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (5). All but one of the strains characterized in this study appeared to be susceptible to penicillin, and only three strains appeared to be resistant to erythromycin (Table 1).

To our knowledge, this is the first time that a vaccine escape strain recombinant due to a capsular switching event has been detected outside the United States. It is debated whether the emergence of the recombinant is due to importation and circulation of strains from the United States or the recombinant originates in an epidemiological picture characterized by high coverage similar to that observed in the United States. Our data underline the importance of postvaccination surveillance in countries that are planning to implement new generations of conjugate vaccines, in order to detect changes in pneumococcal epidemiology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angela Brueggemann for laboratory support for the progeny confirmation of the two recombinants.

We thank Alessandro Zollo, Mauro Trinca, and Pfizer for financial support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ansaldi, F., et al. 2010. Serotype replacement in Streptococcus pneumoniae after conjugate vaccine introduction: impact, doubts and perspective for new vaccines. Rev. Med. Microbiol. 21(3):56-64. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black, S., et al. 2006. Impact of the use of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on disease epidemiology in children and adults. Vaccine 24(Suppl. 2):79-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brueggemann, A. B., R. Pai, D. W. Crook, and B. Beall. 2007. Vaccine escape recombinants emerge after pneumococcal vaccination in the United States. PLoS Pathog. 3(11):e168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 19 April 2010, accession date. Streptococcus laboratory: PCR deduction of pneumococcal serotypes. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/pcr.htm.

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2010. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 20th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S20. CLSI, Wayne, PA.

- 6.Enright, M. C., and B. G. Spratt. 1998. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology 144:3049-3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gherardi, G., et al. 2007. Antibiotic-resistant invasive pneumococcal clones in Italy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:306-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanage, W. P., et al. 2010. Evidence that pneumococcal serotype replacement in Massachusetts following conjugate vaccination is now complete. Epidemics 2(2):80-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang, S. S., et al. 2009. Continued impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on carriage in young children. Pediatrics 124:e1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pai, R., R. E. Gertz, and B. Beall. 2006. Sequential multiplex PCR approach for determining capsular serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:124-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilishvili, T., et al. 2010. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 201:32-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vestrheim, D. F., E. A. Høiby, I. S. Aaberge, and D. A. Caugant. 2010. Impact of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccination program on carriage among children in Norway. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17:325-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]