Abstract

Infections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (MR-CNS) are a serious problem in hospitals because these bacteria produce penicillin-binding protein 2′ (PBP2′ or PBP2a), which shows low affinity to β-lactam antibiotics. Furthermore, the bacteria show resistance to a variety of antibiotics. Identification of these pathogens has been carried out mainly by the oxacillin susceptibility test, which takes several days to produce a reliable result. We developed a simple immunochromatographic test that enabled the detection of PBP2′ within about 20 min. Anti-PBP2′ monoclonal antibodies were produced by a hybridoma of recombinant PBP2′ (rPBP2′)-immunized mouse spleen cells and myeloma cells. The monoclonal antibodies reacted only with PBP2′ of whole-cell extracts and showed no detectable cross-reactivity with extracts from other bacterial species tested so far. One of the monoclonal antibodies was conjugated with gold colloid particles, which react with PBP2′, and another antibody was immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane, which captures the PBP2′-gold colloid particle complex on a nitrocellulose strip. This strip was able to detect 1.0 ng of rPBP2′ or 2.8 × 105 to 1.7 × 107 CFU of MRSA cells. The cross-reactivity test using 15 bacterial species and a Candida albicans strain showed no detectable false-positive results. The accuracy of this method in the detection of MRSA and MR-CNS appeared to be 100%, compared with the results obtained by PCR amplification of the PBP2′ gene, mecA. This newly developed immunochromatographic test can be used for simple and accurate detection of PBP2′-producing cells in clinical laboratories.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (MR-CNS) are the major pathogens causing nosocomial infections and have been increasingly isolated in recent years from patients with community-acquired infections (23, 26, 29). These pathogens often show resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics, including β-lactams, macrolides, tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, and more (19). Therefore, the infections caused by MRSA and MR-CNS are difficult to eradicate. Studies have reported a high mortality rate among patients with MRSA septicemia compared with the mortality caused by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) (4, 25). A characteristic feature of MRSA and MR-CNS is the production of penicillin-binding protein 2′ (PBP2′ or PBP2a), an enzyme involved in the final step of peptidoglycan synthesis which consists of 668 amino acid residues and has a molecular mass of 76 kDa (5, 23a). PBP2′ is not inhibited by most β-lactam antibiotics, and thus, PBP2′-producing isolates show resistance to most, if not all, β-lactam antibiotics. Since the infection progresses very rapidly, a simple and accurate method to detect the PBP2′-producing pathogens is needed to facilitate appropriate chemotherapy and infection control.

Conventionally, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus (MRS) has been detected by the oxacillin or cefoxitin susceptibility assay based on the disk diffusion method or a method to determine the MIC. However, these methods require several days to produce a reliable result. Alternatively, PCR amplification of the mecA gene encoding PBP2′ has been developed (8, 22). Although this method fulfills requirements for high speed, sensitivity, and specificity, it is costly, requires skilled personnel, and needs advanced equipment. Therefore, it is not practical for routine testing in clinical laboratories. Accordingly, a simple and accurate method of MRS detection has been long awaited.

This study reports on the development of an immunochromatographic test (ICT) that can fulfill the requirements for the detection of PBP2′ using novel monoclonal antibodies. The reliability of this method was assessed using clinical isolates of S. aureus and CNS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of His-tagged recombinant PBP2′ (rPBP2′).

DNA was purified from Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain 92-1191, isolated from the blood of a septicemia patient using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen K.K., Tokyo, Japan). The mecA gene was amplified by PCR using a pair of primers, 5′-TAATCCATGGCTTCAAAAGATAAAGAAAT-3′ (nucleotides 70 to 89) and 5′-TAATAAGCTTGTTTTGATATTCATCTATATCGTA-3′ (nucleotides 1990 to 2006), which contain the restriction sites NcoI and HindIII, respectively. PCR was carried out with PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) under the following conditions. After initial denaturation of DNA at 94°C for 3 min with a Gene Amp PCR System 9700 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems Japan, Tokyo, Japan), a program was set at 94°C for 30 s, 57°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 10 s for a total of 30 cycles and then 72°C for 5 min for the termination. Amplified mecA DNA of 1,963 bp, corresponding to the mature PBP2′ protein with deletion of the N-terminal membrane-spanning segment (amino acid residues 24 to 668), was treated with NcoI and HindIII and was ligated to the pETBlue2 vector (Novagen, Madison, WI). Escherichia coli Novablue(DE3) (Novagen) cells were transformed with the plasmid by the heat shock method, and blue-white colonies were selected on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar (Nippon Becton, Dickinson and Company, Tokyo, Japan) containing 50 μg/ml of carbenicillin, 12.5 μg/ml of tetracycline, 80 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and 70 μg/ml of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (X-Gal). E. coli strain Tuner(DE3)/pLacI (Novagen) was transformed with the pETBlue2-mecA plasmid prepared with QIAprep Miniprep (Qiagen) from the white-colony cells.

The transformants were cultured in LB broth containing 50 μg/ml of carbenicillin and 34 μg/ml of chloramphenicol at 37°C until absorbance at 578 nm reached 0.6. Expression of His-tagged rPBP2′ was induced by adding 0.5 mM IPTG, and the culture was then incubated at 22°C for an additional 24 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 20 min and washed twice with a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl and 0.3 M NaCl (pH 8.0). The pellets were resuspended in a solution of 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.3 M NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole (pH 8.0); subjected to ultrasonic oscillation for a total 10-min by 20-s exposure and 30-s intermittent cooling using an Astrason3000 sonicator (Misonix, Melville, NY) at dial setting 5, and then centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The clear soluble fraction was applied to a nickel-ion immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) resin column (Bio-Rad Laboratories, K.K., Tokyo, Japan) equilibrated with a solution of 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.3 M NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole (pH 8.0) and then washed with the same solution; the column was eluted with a solution of 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.3 M NaCl, and 250 mM imidazole (pH 8.0). Neighboring fractions containing the rPBP2′ protein were pooled and dialyzed against a large excess of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 20 mM imidazole. The protein concentration was quantified by the Lowry method with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K., Kanagawa, Japan).

Electrophoresis and Western blotting.

Crude extracts of the transformant cells and purified rPBP2′ were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (10%) electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Protein bands were visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) or Western blotting using anti-His tag antibody (Qiagen K.K., Tokyo, Japan). For Western blotting, proteins were electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Atto Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The membrane was treated as follows: it was blocked with PBS containing 4.0% Block Ace (DS Pharma Biomedical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan)-0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at 24°C, washed 4 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, incubated with 100 ng/ml of anti-His tag antibody at 4°C overnight, washed 4 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, incubated with 1,000-fold-diluted horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse Ig (Dako Japan, Tokyo, Japan) at 24°C for 1 h, washed 4 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, and then soaked in a solution containing 0.2 mg/ml of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and 0.0045% H2O2 for color development.

Preparation of anti-PBP2′ monoclonal antibodies.

Anti-PBP2′ monoclonal antibodies were produced according to the standard protocol described elsewhere (12). Briefly, 8-week-old female BALB/c Cr Slc mice (Japan SLC, Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) were immunized intraperitoneally with 50 μg of rPBP2′ in 250 μl of PBS mixed with an equal volume of Freund's complete adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI). A booster was given on day 14 with 50 μg of rPBP2′ mixed with Freund's incomplete adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) and on day 25 with 50 μg of rPBP2′ in 100 μl of PBS intravenously. The serum titers of immunized mice were measured on day 20 by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), described below. The spleen cells were isolated from the immunized mice on day 28 and fused with P3X63-Ag8.653 with polyethylene glycol 1500 (PEG 1500; Roche Diagnostics K.K., Tokyo, Japan). Hybridoma cells producing anti-PBP2′ antibody were screened by indirect ELISA, cloned twice by the limiting dilution method, and injected intraperitoneally into 13-week-old male BALB/c Cr Slc mice pretreated with pristane. Ascites fluid was collected after 1 to 2 weeks. Monoclonal IgG and IgM were purified from the ascites fluid using a Hitrap protein A HP column (GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo, Japan) and a Kaptiv-M column (Tecnogen S.p.A., Piana di Monte Verna, Italy), respectively, according to the manufacturer's protocol. The antibody isotype and the IgG subclass were determined by ELISA using secondary antibodies (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA).

Indirect ELISA.

The anti-PBP2′ antibody was detected by indirect ELISA. Wells of a microtiter plate were coated with 0.5 μg/ml of rPBP2′ in 10 mM sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.3) at 4°C overnight and then blocked with 10 mM sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.3) containing 0.5% BSA at 24°C for 1 h after two washes. The following materials were sequentially added to the wells: mouse serum (for screening of antibody-producing mice) or hybridoma culture supernatant (for screening of antibody-producing hybridoma) that had been diluted with buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 1% BSA, pH 7.0 (sample buffer), and incubated at 24°C for 1 h; HRP-conjugated anti-mouse Ig that had been diluted 4,000-fold with sample buffer and then incubated at 24°C for 1 h after being washed with a solution consisting of BSA-free sample buffer (washing buffer); and the tetramethyl benzidine (TMB) Microwell peroxidase substrate system (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), which was used after the final washing with washing buffer. The reaction was terminated by adding 50 μl of 1.0 M phosphoric acid. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured with an EL808 Ultra microplate reader (Biotek Instruments, Vermont).

Specificity test of monoclonal antibody.

The cell membrane fraction was prepared from MRSA 92-1191, isolated from the blood of a septicemia patient, and MSSA FDA209P, an FDA reference strain, by the previously reported method (23a) and subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE, and then the protein bands were blotted on a PVDF membrane. The membrane was treated by the following steps: it was blocked with PBS containing 4.0% Block Ace and 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at 24°C; incubated with PBS containing 0.4% Block Ace, 0.1% Tween 20, and 10% normal rabbit serum at 4°C overnight; washed 4 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20; and incubated with 1,000-fold-diluted ascites fluid (clones 10G2 and 1G12) at 24°C for 0.5 h. Following washing and color development, the steps were similar to those described above.

Cross-reactivity of the monoclonal antibody.

Cross-reactivity of the monoclonal antibody against microorganisms was assayed by indirect ELISA. Strains used were S. aureus K744 (MRSA), S. aureus FDA209P (MSSA), Staphylococcus epidermidis clinical isolate no. 1, Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Enterococcus faecium NCTC12204, Escherichia coli NIHJ JC-2, Klebsiella pneumoniae NCTC9632, Serratia marcescens IFO12648, Enterobacter cloacae IFO13535, Enterobacter aerogenes NCTC10006, Pseudomonas aeruginosa E-2, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus IFO12552, and Candida albicans ATCC 10231. These strains were grown on Trypticase soy agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood (Nippon Becton, Dickinson and Company) at 35°C for 18 h. Streptococcus pyogenes GTC262, Streptococcus agalactiae GTC1234, and group C Streptococcus clinical isolate no. 1 were cultured on Trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood in the presence of 5% carbon dioxide at 35°C for 18 h. Cells were suspended in 1.0 ml of sterile deionized water. Absorbance at 578 nm was adjusted to 2.0, and the suspension was mixed with an equal volume of 0.2 M NaOH, boiled for 3 min, and neutralized with 0.5 ml of 0.5 M KH2PO4. Microtiter plates were coated with 50 μl of the cell extracts at room temperature for 2 h, washed twice with PBS, blocked with 100 μl of PBS containing 2% skim milk for 1 h at 24°C, and washed with washing buffer; 100 μl of washing buffer containing 10% normal rabbit serum was added, and then the plates were incubated at 24°C for 1 h and then washed with washing buffer, after which 50 μl of 1,000 ng/ml anti-PBP2′ monoclonal antibody was added and the plates were incubated at 24°C for 0.5 h. This material was subjected to the indirect ELISA described above.

Preparation of the immunochromatographic strip.

Anti-PBP2′ monoclonal IgM (clone 1G12) and anti-mouse IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) were immobilized on a 2.5- by 0.5-cm nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA) at 1.0 and 1.5 cm, respectively, from the proximal end (see Fig. 4). These two lines served as a test line and a control line, respectively. The membrane was blocked with 0.5% casein solution for 20 min. After washing, it was soaked in 3% sucrose solution and air dried. To prepare the gold colloid-conjugated IgG, 1.0 ml of 0.006% gold colloid suspension (40 nm) (Tanaka Kikinzoku Kogyo, Tokyo, Japan) and 0.1 ml of 60 μg/ml anti-PBP2′ monoclonal IgG (clone 10G2) were mixed, incubated for 20 min, and then blocked by addition of 1.0% sodium casein. The mixture was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min to remove free IgG, and the pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer containing 0.1% sodium casein and 10% d-(+)-trehalose dihydrate, pH 8.2. Preparation of the immunochromatographic strip has been described in the supplemental material of reference 15.

Sensitivity and cross-reactivity testing of ICT.

The sensitivity of ICT was evaluated using quantified rPBP2′ (see above) and extracts from three MRSA strains: MRSA ATCC 43300, MRSA 92-1191, and MRSA 70. The cells were grown on Trypticase soy agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood at 35°C for 18 h, suspended in sterile deionized water. The viable cell number was counted on Mueller-Hinton agar. The antigen was extracted by heating a mixture of 50 μl each of cell suspension (or rPBP2′ solution) and 0.2 M NaOH in a boiling water bath for 3 min, and the solution was neutralized by adding 25 μl of 0.5 M KH2PO4 containing 2.5% BSA. The rPBP2′ preparation was diluted with adjustment to 0.2 to 50 ng protein/50 μl/test, or the cell suspension was serially diluted in 10× increments to 104 to 108 CFU equivalent/test. A 50-μl aliquot of the extracts and 10 μl of gold colloid-conjugated antibody suspension were mixed in a well, and an immunochromatographic strip was left to stand in it. The chromatograph was developed for 10 min, and the reaction products at the test line and the control line were observed macroscopically.

The cross-reactivity test was carried out using the strains used for indirect ELISA, except for the MRSA strains. The cell suspension was prepared to the level of 108 CFU of bacteria/test or to 107 CFU of fungi/test. The antigen was extracted as described above and subjected to ICT.

Stability of monoclonal antibody and reproducibility of ICT.

The thermostability of ICT was evaluated by the accelerated stability test. The IgM immobilized membrane strips were kept at 60°C for 5, 10, 21, and 30 days. The detection limit using the MRSA 92-1191 cells was evaluated in the same manner as described above. For the evaluation of reproducibility of ICT, intra- and interassay comparisons were performed using 2 strains each of clinical isolates of MRSA and MSSA. The strains used were cultured on Trypticase soy agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood at 35°C for 18 h, and a loopful (1 μl) of cells from the colonies was suspended in 100 μl of 0.1 M NaOH. After boiling, the assay was performed in the same manner as described above.

Evaluation of ICT using clinical isolates of S. aureus and CNS.

The reliability of ICT was tested using 62 and 53 clinical isolates of S. aureus and CNS, respectively, and the results were compared with those obtained by PCR and the latex aggregation test (LAT) (MRSA-Screen; Denka Seiken Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The antigen extraction for ICT is described above. The LAT was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplification of mecA was reported previously (10).

RESULTS

Preparation of His-tagged rPBP2′.

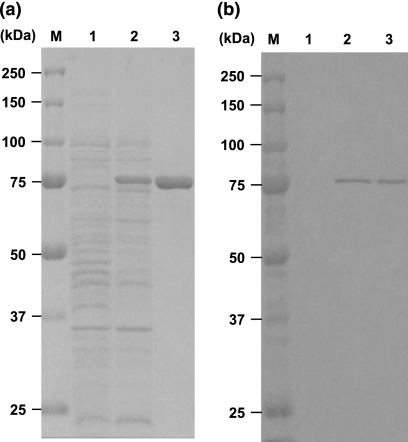

The mecA gene encoding amino acid residues 24 to 668 of PBP2′ was cloned on pETBlue2 with the sequence for hexahistidine residues. E. coli strain Tuner(DE3)/pLacI harboring pETBlue2-mecA was grown in the presence of IPTG, and the extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE. A large amount of protein corresponding to about 75 kDa was confirmed (Fig. 1a, lane 2), and the affinity-purified material showed only a single protein band corresponding to 75 kDa (Fig. 1a, lane 3). Western blotting using anti-His tag antibody also showed a single band corresponding to 75 kDa (Fig. 1b, lanes 2 and 3).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of the soluble fraction and purified rPBP2′. The soluble fraction was prepared from E. coli strain Tuner(DE3)/pLacI cells harboring the pETBlue2-mecA plasmid in the presence and absence of IPTG. The rPBP2′ protein was purified by Ni-resin affinity chromatography from cells cultured in the presence of IPTG. Materials were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. (a) The soluble fraction (20 μg) and purified rPBP2′ (5 μg) were applied. The gel was stained with CBB. (b) The soluble fraction (500 ng) and purified rPBP2′ (100 ng) were applied and transferred to a PVDF membrane after electrophoresis. The membrane was stained by the Western blotting method using anti-His tag antibody. Lanes M, molecular mass markers; lanes 1, soluble fraction from uninduced cells; lanes 2, soluble fraction from IPTG-induced cells; lanes 3, affinity purified rPBP2′.

Specificity and cross-reactivity of novel monoclonal antibodies.

Mice were immunized with the purified rPBP2′, and antibody titer against rPBP2′ was measured by indirect ELISA. All the sera from the immunized mice showed high titers of anti-rPBP2′ antibody, whereas the preimmune sera showed no detectable anti-rPBP2′ antibody (data not shown). The mouse which produced the highest titer of anti-rPBP2′ antibody was selected for hybridoma cell production. Hybridoma cells prepared from the spleen cells of this mouse were screened for the production of monoclonal antibodies. Two hybridoma cells, 10G2 and 1G12, were cloned after two limited dilutions and were then injected into the mouse peritoneal cavity.

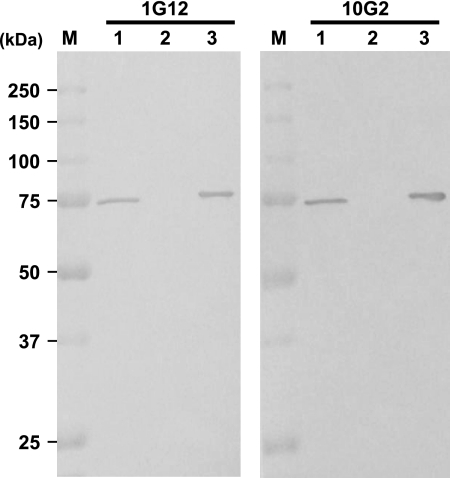

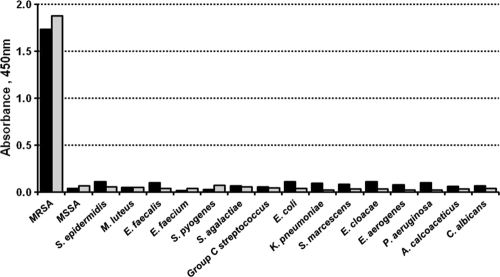

To evaluate the specificity of the anti-rPBP2′ antibody, the reactivity of the mouse ascites fluid was examined by using purified rPBP2′ and the crude membrane fraction from MRSA and MSSA cells by the Western blotting method. Both ascites showed only a single protein band with the membrane fraction from the MRSA cells and rPBP2′ at the position corresponding to a mass of 75 kDa, whereas no protein band was seen in the membrane fraction from the MSSA cells (Fig. 2). To test the cross-reactivity of the antibodies, 16 bacterial species and one fungal species were examined by indirect ELISA. The purified monoclonal antibodies 1G12 and 10G2 showed positive results only with the MRSA extracts, not with extracts from the remaining 15 bacterial species and a fungal species (Fig. 3). The antibody isotype and IgG subclass of 1G12 and 10G2 were found to be IgM and IgG1, respectively, as tested with specific antibodies by ELISA.

FIG. 2.

Specificity test of the monoclonal antibodies by the Western blot analysis. The purified rPBP2′ and the crude membrane fraction from the MRSA and MSSA cells were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE, and the protein bands were transferred to a PVDF membrane. The specificity of the monoclonal antibodies (1G12 and 10G2) was tested by the Western blotting method. Lanes M, molecular mass markers; lanes 1, crude membrane fraction from MRSA cells; lanes 2, crude membrane fraction from MSSA cells; lanes 3, purified rPBP2′.

FIG. 3.

Cross-reactivity of monoclonal antibodies tested by indirect ELISA. The antigen of the test cells was immobilized in the microplate wells and subjected to ELISA using the monoclonal antibodies 10G2 and 1G12. Black columns, 1G12; gray columns, 10G2.

Performance of ICT.

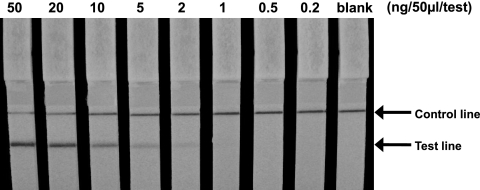

The ICT system was prepared using two monoclonal antibodies, 10G2 and 1G12. The 10G2 antibody was combined with a colloidal gold particle in a complex that served as the detector of PBP2′, and the 1G12 antibody was immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane that captured the 10G2-gold colloid-PBP2′ complex, thereby forming an antigen sandwich with two monoclonal antibodies. To evaluate the sensitivity of the ICT, homogeneously purified rPBP2′ protein was used first. The test strip was able to detect levels as low as 1.0 ng/50 μl/test of rPBP2′ but was unable to detect protein at levels lower than 0.5 ng/test, macroscopically (Fig. 4). In the next experiment, whole-cell extracts from three MRSA strains were subjected to ICT. The results showed that the ICT was able to detect 1.7 × 107, 4.7 × 105, and 2.8 × 105 CFU/test of MRSA ATCC 43300, MRSA 70, and MRSA 92-1191, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Sensitivity of ICT to the purified rPBP2′. Purified rPBP2′ protein was diluted, with adjustment of the protein concentration from 0.2 to 50 ng/50 μl/test, and was subjected to ICT for 10 min.

To test for cross-reactivity of the present ICT, 16 strains from 15 bacterial species and one strain of Candida albicans at the cell density of 108 CFU/test and 107 CFU/test, respectively, were examined. The results clearly showed that none of these cells yielded false-positive reactions.

The thermostability of monoclonal antibody immobilized on the membrane strip was evaluated by an accelerated stability test at 60°C. The monoclonal antibody-immobilized strips were kept for 5, 10, 21, and 30 days, and the sensitivity was tested. We found that the sensitivity in detection of the MRSA 92-1191 cells was totally unchanged even after storage for 30 days (data not shown). To evaluate the reproducibility of the ICT, intra- and interassay comparisons were performed using two strains each of MRSA and MSSA from clinical sources. Five repeated experiments using two MRSA and two MSSA strains simultaneously showed identical positive and negative results, respectively. In addition, repeated experiments on 5 consecutive days also showed identical positive and negative results in 2 MRSA and 2 MSSA strains, respectively. It was firmly established that the present ICT has high reproducibility and is specific to the PBP2′-producing cells.

Reliability of the present ICT and comparison with PCR and LAT.

To test the reliability of the newly developed ICT, 62 clinical isolates of S. aureus and 53 clinical isolates of CNS were examined. One loopful (1 μl) of cells was subjected to ICT, and the results were compared with those of PCR and LAT (Table 1 ). As mentioned above, PCR detects the mecA gene and LAT detects the PBP2′ protein. Among 62 strains of S. aureus tested, PCR detected the mecA gene from 37 strains, and 25 strains were mecA negative. The ICT and LAT showed results consistent with those of PCR without exception. Thus, it was established that ICT, PCR, and LAT are equally good methods for differentiating MRSA from MSSA. Among 53 strains of CNS, the present ICT method yielded PBP2′ protein positivity in 38 strains and negativity in 15 strains, which matched perfectly with the results obtained by PCR. However, LAT was able to detect PBP2′ in only 28 CNS strains and the remaining 25 strains appeared to be negative for PBP2′. Thus, LAT failed to detect 10 mecA-positive- and PBP2′-positive CNS strains, resulting in false-negative results.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of results obtained by PCR, LAT, and ICT using clinically isolated strainsa

| Test | No. of samples |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S. aureus |

CNS |

|||||

| Total | Positive | Negative | Total | Positive | Negative | |

| PCR | 62 | 37 | 25 | 53 | 38 | 15 |

| LAT | 62 | 37 | 25 | 53 | 28 | 25 |

| ICT | 62 | 37 | 25 | 53 | 38 | 15 |

Abbreviations: LAT, latex aggregation test; ICT, immunochromatographic test; CNS, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus.

DISCUSSION

Identification of MRSA and MR-CNS mainly relies on the β-lactam susceptibility test for oxacillin or cefoxitin (3). The biggest drawback of the culture method is that it is time-consuming, requiring more than 1 day to obtain a result from isolated colonies. PCR amplification of the marker gene(s) was adopted for rapid and accurate detection of MRSA and MR-CNS. Recently, a new real-time PCR method that amplifies the right-extremity sequences of the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) element and the 3′ end of the S. aureus orfX gene has been developed (11). This method has enabled MRSA to be detected directly from clinical specimens. Though the PCR method is highly sensitive, accurate, and rapid, only a limited number of clinical laboratories have the opportunity to use and run the expensive equipment. Moreover, the method requires highly trained technical experts using costly reagents. The alternative method employed currently is to detect the PBP2′ protein by the latex aggregation method (17). Though this is a time-saving method, the greatest drawback is that the target microorganism is limited to MRSA. Therefore, it is questionable whether the latex aggregation method can be applied to the detection of MR-CNS.

In this paper, we have reported a simple, time-saving method of ICT for detecting PBP2′ using the extracts from pure culture cells. Since our ICT method employed monoclonal antibodies against rPBP2′, the specificity was extremely high. In fact, the whole-cell extracts of MSSA and MRSA showed no detectable protein band except for PBP2′.

The ICT method using the 1G12 and 10G2 monoclonal antibodies was able to detect levels from 2.8 × 105 to 1.7 × 107 CFU/test of MRSA. We found an approximately 60-fold difference in the level of PBP2′ expression among the MRSA strains tested so far. In fact, the reference strain ATCC 43300 contains a heterogeneous population of cells in regard to oxacillin susceptibility (14). On the other hand, the clinically isolated strains 92-1191 and 70 showed stable, high oxacillin resistance, with an MIC of ≥128 μg/ml.

Cross-reactivity testing of the present ICT revealed that there was absolutely no cross-reaction when 15 different species of bacteria and a Candida albicans strain were tested. One important point to be considered is that Staphylococcus aureus produces protein A (6), which reacts with the Fc region of IgG, potentially causing false-positive results in immunoassay systems (18, 20). We used the monoclonal antibodies to IgG1 and IgM for the present ICT. Fortunately, it is generally accepted that the binding affinity of protein A to mouse IgG1 and IgM is lower than that to other subclasses of mouse IgG (7).

Another point to be clarified would be the stability of IgM antibody on the membrane strip because it is said that IgM is generally less stable than IgG. Thus, we tested the stability of our IgM monoclonal antibody (clone 1G12) on the immobilized membrane strip by the accelerated stability test at 60°C up to 30 days. We found no detectable deterioration of our IgM antibody in the reaction with the PBP2′-producing cells. It was generally accepted that stability at 60°C for 3 weeks is equivalent to that for 2 years of storage at room temperature (2, 21). It was reported that a sugar additive such as sucrose or trehalose protects proteins from deterioration under the dried condition (21). Our membrane strips were soaked in 3% sucrose solution before being dried.

The performance of ICT was first tested using a total of 62 strains of clinically isolated S. aureus, and the results were compared with those of PCR and commercially available LAT. ICT, LAT, and PCR all detected PBP2′ positivity in 37 strains, thereby indicating that all three methods were equally effective for detecting PBP2′-positive S. aureus. The present result confirmed previous reports that the sensitivity and specificity of LAT were 96.7 to 100% and 99.2 to 100%, respectively, in S. aureus (1, 24, 28). Since LAT is recommended by the manufacturer for use in detecting MRSA, the performance of this kit may be acceptable.

Similarly, 53 strains of CNS were tested and ICT detected PBP2′ in 38 strains with sensitivity and specificity 100% identical to those obtained by PCR. On the other hand, LAT showed only 73.6% sensitivity and 100% specificity. MR-CNS strains often show heterogeneous levels of mecA gene expression, and therefore, the use of an increased amount of cells for the LAT was evaluated (9, 13). In fact, it has been reported that the use of 2.5-times-more cells and extension of incubation to 10 min improved the sensitivity of LAT for CNS from 68.4 to 95.7% (27). However, the application of this modified method to S. aureus caused false-positive results (16), which were most likely attributable to reaction with protein A. Our ICT method was able to detect PBP2′ from MRSA and MR-CNS correctly, because of the improvement in the detection limits compared with those of LAT.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study show that the newly developed ICT is a highly sensitive, accurate, and rapid method for the detection of PBP2′-producing Staphylococcus spp. from pure cultures. Therefore, this method is suitable for use in routine tests at clinical laboratories.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants-in-aid from the Food Safety Commission, Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cavassini, M., A. Wenger, K. Jaton, D. S. Blanc, and J. Bille. 1999. Evaluation of MRSA-Screen, a simple anti-PBP 2a slide latex agglutination kit, for rapid detection of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1591-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chanteau, S., et al. 2006. New rapid diagnostic tests for Neisseria meningitidis serogroups A, W135, C, and Y. PLoS Med. 3:e337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2009. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility testing for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 8th ed. CLSI document M07-A8. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 4.Cosgrove, S. E., et al. 2003. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:53-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Jonge, B. L., and A. Tomasz. 1993. Abnormal peptidoglycan produced in a methicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus grown in the presence of methicillin: functional role for penicillin-binding protein 2A in cell wall synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:342-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsgren, A., and J. Sjoquist. 1966. “Protein A” from S. aureus. I. Pseudo-immune reaction with human gamma-globulin. J. Immunol. 97:822-827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harlow, E., and D. Lane (ed.). 1988. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 8.Hogg, G. M., J. P. McKenna, and G. Ong. 2008. Rapid detection of methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus directly from positive BacT/Alert blood culture bottles using real-time polymerase chain reaction: evaluation and comparison of 4 DNA extraction methods. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 61:446-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horstkotte, M. A., J. K. Knobloch, H. Rohde, and D. Mack. 2001. Rapid detection of methicillin resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci by a penicillin-binding protein 2a-specific latex agglutination test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3700-3702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hososaka, Y., et al. 2006. Nosocomial infection of beta-lactam antibiotic-induced vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (BIVR). J. Infect. Chemother. 12:181-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huletsky, A., et al. 2004. New real-time PCR assay for rapid detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus directly from specimens containing a mixture of staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1875-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohler, G., and C. Milstein. 1975. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature 256:495-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louie, L., A. Majury, J. Goodfellow, M. Louie, and A. E. Simor. 2001. Evaluation of a latex agglutination test (MRSA-Screen) for detection of oxacillin resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4149-4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackenzie, A. M., H. Richardson, R. Lannigan, and D. Wood. 1995. Evidence that the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards disk test is less sensitive than the screen plate for detection of low-expression-class methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1909-1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsui, H., et al. 2009. Rapid detection of vaginal Candida species by newly developed immunochromatography. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:1366-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, M. B., H. Meyer, E. Rogers, and P. H. Gilligan. 2005. Comparison of conventional susceptibility testing, penicillin-binding protein 2a latex agglutination testing, and mecA real-time PCR for detection of oxacillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3450-3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakatomi, Y., and J. Sugiyama. 1998. A rapid latex agglutination assay for the detection of penicillin-binding protein 2′. Microbiol. Immunol. 42:739-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen, H. M., M. A. Rocha, K. R. Chintalacharuvu, and D. O. Beenhouwer. 2010. Detection and quantification of Panton-Valentine leukocidin in Staphylococcus aureus cultures by ELISA and Western blotting: diethylpyrocarbonate inhibits binding of protein A to IgG. J. Immunol. Methods 356:1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niki, Y., et al. 2008. The first nationwide surveillance of bacterial respiratory pathogens conducted by the Japanese Society of Chemotherapy. Part 1: a general view of antibacterial susceptibility. J. Infect. Chemother. 14:279-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Notermans, S., P. Timmermans, and J. Nagel. 1982. Interaction of staphylococcal protein A in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for detecting staphylococcal antigens. J. Immunol. Methods 55:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paek, S. H., S. H. Lee, J. H. Cho, and Y. S. Kim. 2000. Development of rapid one-step immunochromatographic assay. Methods 22:53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakoulas, G., et al. 2001. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: comparison of susceptibility testing methods and analysis of mecA-positive susceptible strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3946-3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shibuya, Y., et al. 2008. Emergence of the community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 clone in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 14:439-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Utsui, Y., and T. Yokota. 1985. Role of an altered penicillin-binding protein in methicillin- and cephem-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 28:397-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Leeuwen, W. B., C. van Pelt, A. Luijendijk, H. A. Verbrugh, and W. H. Goessens. 1999. Rapid detection of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates by the MRSA-screen latex agglutination test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3029-3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitby, M., M. L. McLaws, and G. Berry. 2001. Risk of death from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: a meta-analysis. Med. J. Aust. 175:264-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wisplinghoff, H., et al. 2004. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:309-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamazumi, T., I. Furuta, D. J. Diekema, M. A. Pfaller, and R. N. Jones. 2001. Comparison of the Vitek gram-positive susceptibility 106 card, the MRSA-Screen latex agglutination test, and mecA analysis for detecting oxacillin resistance in a geographically diverse collection of clinical isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3633-3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamazumi, T., et al. 2001. Comparison of the Vitek gram-positive susceptibility 106 card and the MRSA-screen latex agglutination test for determining oxacillin resistance in clinical bloodstream isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:53-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zetola, N., J. S. Francis, E. L. Nuermberger, and W. R. Bishai. 2005. Community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an emerging threat. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5:275-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]