Abstract

The coadministration of the combined meningococcal serogroup C conjugate (MCC)/Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) and measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine at 12 months of age was investigated to assess the safety and immunogenicity of this regimen compared with separate administration of the conjugate vaccines. Children were randomized to receive MCC/Hib vaccine alone followed 1 month later by PCV7 with MMR vaccine or to receive all three vaccines concomitantly. Immunogenicity endpoints were MCC serum bactericidal antibody (SBA) titers of ≥8, Hib-polyribosylribitol phosphate (PRP) IgG antibody concentrations of ≥0.15 μg/ml, PCV serotype-specific IgG concentrations of ≥0.35 μg/ml, measles and mumps IgG concentrations of >120 arbitrary units (AU)/ml, and rubella IgG concentrations of ≥11 AU/ml. For safety assessment, the proportions of children with erythema, swelling, or tenderness at site of injection or fever or other systemic symptoms for 7 days after immunization were compared between regimens. No adverse consequences for either safety or immunogenicity were demonstrated when MCC/Hib vaccine was given concomitantly with PCV and MMR vaccine at 12 months of age or separately at 12 and 13 months of age. Any small differences in immunogenicity were largely in the direction of a higher response when all three vaccines were given concomitantly. For systemic symptoms, there was no evidence of an additive effect; rather, any differences between schedules showed benefit from the concomitant administration of all three vaccines, such as lower overall proportions with postvaccination fevers. The United Kingdom infant immunization schedule now recommends that these three vaccines may be offered at one visit at between 12 and 13 months of age.

In September 2006, the combined meningococcal serogroup C (MCC) and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) conjugate vaccine (Menitorix; GlaxoSmithKline [GSK]) was introduced in the United Kingdom as a booster dose given in the second year of life (2). At that time there were no data on the immunogenicity of the combined MCC/Hib vaccine when coadministered with measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7), both of which are also given early in the second year of life. Because of unpredictable immunological interactions when different polysaccharide conjugates are given concomitantly for primary immunization, it was recommended that the MCC/Hib vaccine should be given at 12 months, followed by PCV7 and MMR vaccine at 13 months (2).

Following the launch of the new booster program, health professionals and parents began to ask whether, for convenience, all three vaccines could be given at the same visit. At the time, a study to evaluate the immunogenicity of reduced primary immunization schedules involving two doses of PCV7 given concomitantly with MCC vaccine was being conducted (6, 14). Children in the study were subsequently recruited into a booster study and offered MCC/Hib vaccine at 12 months followed by PCV7 and MMR vaccine at 13 months as in the national schedule. In response to the question of whether all three vaccines could be given at the same visit, the design of the booster study was changed, with children now randomized either to receive the vaccines on the existing national schedule or to receive all three vaccines concomitantly. The results of the booster study that are relevant to this question are reported here.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

In the primary phase, children in the study were randomized to receive two doses of one of the three licensed MCC vaccines, either at 2 and 3 or at 2 and 4 months of age with concomitant PCV7 vaccine (Prevenar; Pfizer) (6, 14). Two MCC vaccines are conjugated to CRM197 (MCC-CRM), a nontoxigenic natural variant of diphtheria toxin (Meningitec [Pfizer] and Menjugate [Novartis Vaccines]), and one (NeisVac-C [Baxter Bioscience]) is conjugated to tetanus toxoid (MCC-TT). All infants received three doses of a combined diphtheria/tetanus/five-component acellular pertussis/inactivated poliovirus/Hib-containing vaccine (DTaP5/IPV/Hib-TT) (Pediacel; Sanofi Pasteur MSD) for primary immunization at 2, 3, and 4 months. Any study participant who failed to achieve protective antibody levels to MCC or Hib vaccine after completion of the primary schedule was offered a further dose of the relevant vaccine. Before the primary phase was completed, PCV7 was introduced into the national schedule at 2 and 4 months. An interim analysis showed that PCV7 was poorly immunogenic at 2 to 3 months, so recruitment to this schedule was terminated and those already vaccinated offered an additional PCV7 dose if eligible to have been vaccinated at 2 and 4 months outside the study (6).

At 12 months of age infants were recruited to a booster phase and given the combined MCC/Hib vaccine in which both components are conjugated to TT (Menitorix; GSK) followed by PCV7 and MMR vaccine at 13 months of age. With ethics committee approval, the remaining children who had not yet received their booster vaccinations were randomized either to receive the vaccines on the national schedule (group A) or to receive MCC/Hib vaccine, PCV7, and MMR vaccine concomitantly (group B). The first five children in group A were due for their booster before MCC/Hib vaccine was available and so were given separate MCC and Hib vaccines for boosting. The randomization schedule was designed to achieve approximately similar numbers overall in each group. As permitted by the protocol, a proportion of parents opted for their child not to have MMR vaccine but to remain within the trial and receive just MCC/Hib vaccine with or before PCV7. In order to allow measurement of the sizes of local reactions to study vaccines given at the same time, nurses were instructed to administer each into a different limb.

Immunogenicity.

Blood samples were taken prior to booster vaccination at 12 months, again at 13 months, and for group A only also at 14 months of age. Sera were analyzed for meningococcal serogroup C antibody by the serum bactericidal antibody (SBA) assay using baby rabbit complement as previously described (8). For computational purposes, SBA titers of <4 were assigned a value of 2. A minimum protective antibody level was taken as an SBA titer of ≥8 and a higher titer of 128 for discriminatory purposes. Hib-polyribosylribitol phosphate (PRP) antibodies (IgG) were quantified using a standardized enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with sera titrated against the International anti-Hib quality control serum (Center for Biologics and Evaluation Research [CBER], 1983) (13). The minimum protective antibody level was taken as 0.15 μg/ml. Serotype-specific pneumococcal IgG antibodies were measured by ELISA according to the WHO protocol, with a minimum protective level defined as 0.35 μg/ml (16). IgG antibodies to tetanus toxoid and diphtheria toxoid were also measured by ELISA (9, 10), as the carrier proteins in the conjugate vaccines are immunogenic and can induce booster responses. MMR virus IgG antibodies were quantified by the Food and Drug Administration-approved MMR virus IgG AtheNA Multi-Lyte immunoassay (Zeus Scientific) (4). Results were classified as positive if >120 AU/ml for measles and mumps viruses and ≥ 11 AU/ml for rubella virus. While the optimal interval for assessing the immediate antibody response to conjugate vaccines is 4 weeks, antibodies to the live MMR viral vaccine are still developing at this time. MMR virus antibody levels were therefore also measured at 11 to 12 months after vaccination in samples taken to assess persistence of antibodies to MCC and Hib (1).

Safety assessment.

Parents were provided with a 7-day diary to record systemic and local symptoms in the postvaccination period; those in group A completed two diaries. Parents were provided with rulers to measure the maximum diameter of erythema and swelling at the site of each injection and instructed how to assess pain. Thermometers were provided for parents to take axillary temperatures daily for the week after vaccination. Other symptoms about which information was solicited included decreased feeding, reduced activity, irritability, persistent crying, vomiting, or diarrhea in the week after vaccination.

Statistical analysis.

For analysis of the SBA, Hib, diphtheria toxoid, and tetanus toxoid antibody responses following administration of the MCC/Hib booster, geometric means and proportions above putative protective levels with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated according to whether or not PCV7 was given at the same time. The five children in group A who received separate MCC and Hib vaccines were grouped with MCC/Hib vaccine recipients for the analysis. The final numbers of test results are fewer than those vaccinated for certain immunoassays, in particular for MMR vaccine, due to serum sample volumes being limited.

For the analysis of the serotype-specific pneumococcal responses after PCV7, geometric means and proportions above putative protective levels with 95% CIs were calculated according to whether or not MCC/Hib vaccine was given at the same time. Multivariable regression was performed on the logs of the postbooster antibody levels with explanatory variables of sex, concomitant MCC/Hib vaccine or PCV7, concomitant MMR vaccine, and whether an extra dose of PCV7, MCC vaccine, or Hib vaccine had been given in the primary phase. For interpretation of differences, significance is taken at a 1% level due to the number of tests.

For the safety analysis, comparison between groups A and B was restricted to those given MMR vaccine and who had not received extra doses of MCC vaccine, Hib vaccine, or PCV7 for primary immunization.

RESULTS

A total of 280 children were recruited into the booster study. Of these, 7 had received an extra MCC vaccine dose, 20 an extra dose of Hib vaccine, and 30 an extra dose of PCV7. The numbers in the different booster schedules, including protocol violations, are shown in Table 1. Of the 280 trial participants, 236 (84%) opted for MMR vaccine. Overall, PCV7 and MMR vaccine were given concomitantly with MCC/Hib vaccine on 123 occasions and separately on 157 occasions.

TABLE 1.

Numbers of participants in the booster study according to vaccines given and interval

| Group and vaccine administrationa | No. of participants |

|---|---|

| A | |

| MCC and Hib, then PCV7 and MMR | 5 |

| MCC/Hib and MMR then PCV7 | 1 |

| MCC/Hib, then PCV7 | 26 |

| MCC/Hib, then PCV7 and MMR | 125 |

| MCC/Hib and PCV7, then MMR | 7 |

| B | |

| MCC/Hib, PCV7, and MMR | 98 |

| MCC/Hib and PCV7 | 18 |

“Then” indicates 1 month later.

Antibody responses to MCC, Hib, diphtheria toxoid, and tetanus toxoid after the MCC/Hib booster.

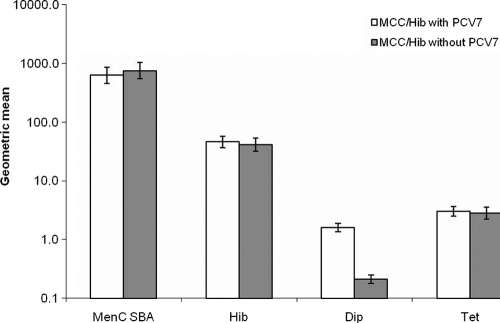

There were no differences in the proportions of participants achieving putative protective thresholds (Table 2) or in geometric mean antibody levels (Fig. 1) to MCC, Hib, or tetanus toxoid after the MCC/Hib booster according to whether PCV7 was given concomitantly or not. A significantly (P < 0.001) higher proportion achieved diphtheria toxoid antibody levels of ≥0.1 or 1.0 IU/ml when PCV7 was given concomitantly, consistent with the booster effect of a CRM conjugate vaccine. The anti-diphtheria toxoid IgG geometric mean concentration (GMC) at 4 weeks after PCV7 when given without MCC/Hib vaccine (1.67; 95% CI, 1.44 to 1.95) was similar to that when given with MCC/Hib vaccine (1.62; 95% CI, 1.37 to 1.91), confirming no attenuation of the booster response to the CRM conjugate component of PCV7 by concomitant administration with another conjugate.

TABLE 2.

Proportions above various cutoff values at 1 month after vaccination according to whether MCC/Hib vaccine was given with or without PCV7

| Measure | Cutoff value | PCV7 | n | Νο. above cutoff value | Proportion above cutoff value (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBA titer | ≥8 | Without | 135 | 130 | 0.96 (0.92-0.99) |

| With | 116 | 113 | 0.97 (0.93-0.99) | ||

| ≥128 | Without | 135 | 124 | 0.92 (0.86-0.96) | |

| With | 116 | 103 | 0.89 (0.82-0.94) | ||

| Hib, μg/ml | ≥0.15 | Without | 137 | 135 | 0.98 (0.94-1.00) |

| With | 117 | 117 | 1.00 (0.97-1.00) | ||

| ≥1.0 | Without | 137 | 134 | 0.98 (0.94-1.00) | |

| With | 117 | 116 | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) | ||

| Diphtheria toxoid, IU/ml | ≥0.1 | Without | 137 | 110 | 0.80 (0.73-0.87) |

| With | 117 | 117 | 1.00 (0.97-1.00) | ||

| ≥1.0 | Without | 137 | 9 | 0.07 (0.03-0.12) | |

| With | 117 | 85 | 0.73 (0.64-0.80) | ||

| Tetanus toxoid, IU/ml | ≥0.1 | Without | 137 | 135 | 0.99 (0.95-1.00) |

| With | 117 | 117 | 1.00 (0.97-1.00) | ||

| ≥1.0 | Without | 137 | 104 | 0.76 (0.68-0.83) | |

| With | 117 | 100 | 0.85 (0.78-0.91) |

FIG. 1.

Geometric mean titers of meningococcal serogroup C SBA and geometric mean concentrations of PRP IgG (μg/ml), diphtheria toxoid IgG (IU/ml), and tetanus toxoid IgG (IU/ml), with 95% CIs, at 1 month after MCC/Hib vaccine administration either with or without PCV7.

The proportion of participants with tetanus toxoid antibody levels of ≥1.0 IU/ml was significantly (P < 0.001) higher after the MCC/Hib booster (80%; 95% CI, 75% to 85%) than before (10%; 95% CI, 7% to 15%), as was the GMC (2.90 IU/ml [95% CI, 2.49 to 3.38 IU/ml] after compared with 0.31 [0.28 to 0.35] before), consistent with the booster effect of the tetanus toxoid conjugate in this vaccine.

Regression analysis on the logs of the antibody levels confirmed significantly higher diphtheria toxoid antibody levels at 1 month after MCC/Hib vaccine administration (2.1-fold [95% CI, 1.7- to 2.4-fold]; P < 0.001) for those given concomitant PCV7. SBA and tetanus toxoid antibody levels were higher postbooster in those who had received a primary MCC-TT schedule (2.1-fold and 1.4-fold, respectively; P < 0.001). Concomitant MMR vaccine administration showed no significant effect at a 1% level for Hib and SBA (22% higher for Hib [P = 0.17] and 6% lower for SBA [P = 0.72]). For diphtheria and tetanus toxoids there was some evidence of higher responses (1.2- and 1.3-fold, respectively; P = 0.02 for both). Those who had required an extra dose of Hib vaccine had significantly lower SBA, Hib, diphtheria toxoid, and tetanus toxoid levels postbooster (41%, 45%, 26%, and 47% lower, respectively; P < 0.001).

Pneumococcal serotype-specific responses after the PCV7 booster.

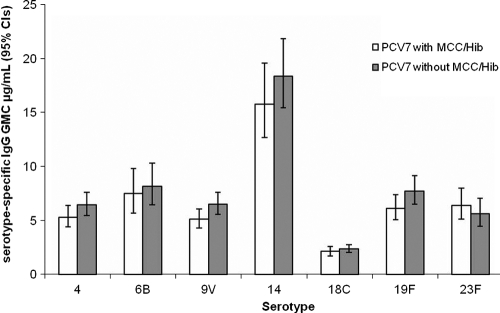

There were no differences in the proportions of participants achieving a putative protective threshold of 0.35 or a higher threshold of 1.0 μg/ml (Table 3) or in GMCs (Fig. 2) for any of the PCV7 serotypes according to whether MCC/Hib vaccine was given concomitantly or not. Regression analysis showed no difference according to whether MCC/Hib or MMR vaccine was given concomitantly. A sex difference was seen for serotype 6B, with males having 19% lower levels (P = 0.004). There was no remaining effect of the primary schedule, i.e., 2/3 versus 2/4 months. Those who had required an extra dose of Hib vaccine had significantly lower antibody concentrations for serotypes 6B (34% lower; P = 0.003) and 23F (35% lower; P < 0.001) but not for other serotypes.

TABLE 3.

Proportions of participants achieving a serotype-specific cutoff antibody level at 4 weeks after the PCV7 booster according to whether MCC/Hib vaccine was given concomitantly

| Serotype | Cutoff value (μg/ml) | MCC/Hib vaccine | No. of sera | No. above cutoff value | Proportion above cutoff value (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | ≥0.35 | Without | 106 | 106 | 1.00 (0.97-1.00) |

| With | 91 | 91 | 1.00 (0.96-1.00) | ||

| ≥1.0 | Without | 106 | 104 | 0.98 (0.93-1.00) | |

| With | 91 | 87 | 0.96 (0.89-0.99) | ||

| 6B | ≥0.35 | Without | 107 | 106 | 0.99 (0.95-1.00) |

| With | 91 | 88 | 0.97 (0.91-0.99) | ||

| ≥1.0 | Without | 107 | 103 | 0.96 (0.91-0.99) | |

| With | 91 | 85 | 0.93 (0.86-0.98) | ||

| 9V | ≥0.35 | Without | 107 | 107 | 1.00 (0.97-1.00) |

| With | 90 | 90 | 1.00 (0.96-1.00) | ||

| ≥1.0 | Without | 107 | 103 | 0.96 (0.91-0.99) | |

| With | 90 | 89 | 0.99 (0.94-1.00) | ||

| 14 | ≥0.35 | Without | 107 | 107 | 1.00 (0.97-1.00) |

| With | 91 | 91 | 1.00 (0.96-1.00) | ||

| ≥1.0 | Without | 107 | 107 | 1.00 (0.97-1.00) | |

| With | 91 | 90 | 0.99 (0.94-1.00) | ||

| 18C | ≥0.35 | Without | 106 | 105 | 0.99 (0.95-1.00) |

| With | 91 | 88 | 0.97 (0.91-0.99) | ||

| ≥1.0 | Without | 106 | 92 | 0.87 (0.79-0.93) | |

| With | 91 | 72 | 0.79 (0.69-0.87) | ||

| 19F | ≥0.35 | Without | 107 | 106 | 0.99 (0.95-1.00) |

| With | 91 | 91 | 1.00 (0.96-1.00) | ||

| ≥1.0 | Without | 107 | 106 | 0.99 (0.95-1.00) | |

| With | 91 | 90 | 0.99 (0.94-1.00) | ||

| 23F | ≥0.35 | Without | 107 | 105 | 0.98 (0.93-1.00) |

| With | 91 | 90 | 0.99 (0.94-1.00) | ||

| ≥1.0 | Without | 107 | 97 | 0.91 (0.83-0.95) | |

| With | 91 | 88 | 0.97 (0.91-0.99) |

FIG. 2.

Pneumococcal serotype-specific IgG GMCs and 95% CIs at 1 month after PCV7 administration with or without MCC/Hib vaccine.

Measles, mumps, and rubella virus IgG antibody at 1 and 12 months following MMR vaccination.

There was no difference in the proportions achieving the protective thresholds or GMCs for measles, mumps, or rubella virus (Table 4) according to whether MCC/Hib vaccine was given concomitantly or not with MMR vaccine and PCV7. Those who had required an extra dose of Hib vaccine did not have lower antibody concentrations for measles, mumps, or rubella virus.

TABLE 4.

Proportions of subjects positive for measles, mumps, and rubella virus antibodies and geometric mean concentrations by time since MMR vaccine coadministered with PCV7 with and without concomitant MCC/Hib vaccine

| Virus | Time (mo) after MMR vaccine | MCC/Hib vaccine | No. of sera | No. positive | Proportion positive (95% CI) | Geometric mean concn (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measles | 1 | With | 90 | 88 | 0.98 (0.92-1.00) | 309.4 (283.0-338.2) |

| 1 | Without | 100 | 99 | 0.99 (0.95-1.00) | 317.2 (293.9-342.3) | |

| 12 | With | 77 | 76 | 0.99 (0.93-1.00) | 372.4 (340.3-407.6) | |

| 11 | Without | 106 | 104 | 0.98 (0.93-1.00) | 336.7 (306.2-370.3) | |

| Mumps | 1 | With | 90 | 87 | 0.97 (0.91-0.99) | 239.2 (223.7-255.8) |

| 1 | Without | 100 | 100 | 1.0 (0.96-1.00) | 266.1 (249.7-283.6) | |

| 12 | With | 77 | 73 | 0.95 (0.87-0.99) | 257.5 (233.1-284.5) | |

| 11 | Without | 106 | 102 | 0.96 (0.91-0.99) | 229.5 (208.5-252.6) | |

| Rubella | 1 | With | 90 | 90 | 1.0 (0.96-1.00) | 87.9 (74.7-103.5) |

| 1 | Without | 100 | 99 | 0.99 (0.95-1.00) | 94.1 (81.7-108.5) | |

| 12 | With | 77 | 77 | 1.0 (0.95-1.00) | 73.7 (66.0-82.4) | |

| 11 | Without | 106 | 105 | 0.99 (0.95-1.00) | 67.2 (59.8-75.6) |

Reactogenicity.

For comparison of reactogenicity between groups A and B, the data were restricted to those who received concomitant MMR vaccine, did not receive an extra dose of Hib, MCC, or PCV7, and had a completed diary returned. The proportions of children with erythema, swelling, or tenderness at the site of injection of MCC/Hib vaccine, PCV7, or MMR vaccine were not significantly different whether the vaccines were given sequentially or at the same time (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Numbers of children with local reactions at the injection site within 7 days of receiving MCC/Hib vaccine and PCV7 with MMR vaccine according to whether given sequentially 1 month apart (group A) or together (group B)

| Local Reaction | No. (%) positive |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCC/Hib vaccine |

PCV7 |

MMR vaccine |

||||

| Group A (n = 108) | Group B (n = 68) | Group A (n = 104) | Group B (n = 68) | Group A (n = 104) | Group B (n = 68) | |

| Any erythema | 24 (22.2) | 18 (26.5) | 43 (41.3) | 26 (38.2) | 28 (26.9) | 19 (27.9) |

| Any swelling | 5 (4.6) | 7 (10.3) | 23 (22.1) | 17 (25.0) | 14 (13.5) | 6 (8.8) |

| Erythema of >3 cm | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 4 (3.8) | 3 (4.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Swelling of >3 cm | 0 | 0 | 3 (2.9) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Tenderness | 8 (7.4) | 11 (16.2) | 17 (16.3) | 13 (19.1) | 18 (17.3) | 8 (11.8) |

For the systemic symptoms for which information was solicited, there was no additive effect when all three vaccines were given concomitantly compared with their sequential administration (Table 6). For example, the proportions with axillary temperatures of >37.5°C at any time in the 7-day postvaccination period were 26.9% when PCV7 was given with MMR vaccine, 8.3% when MCC/Hib vaccine was given alone, and only 19.1% when all three vaccines were given concomitantly.

TABLE 6.

Numbers of children with solicited systemic symptoms within 7 days of vaccination for those given MCC/Hib vaccine followed by PCV7 and MMR vaccine (group A) compared with those given all three vaccines concomitantly (group B)

| Systemic symptom | No. (%) positive |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A, MCC/Hib vaccine (n = 108) | Group A, PCV7 + MMR vaccine (n = 104) | Group B, PCV7 + MCC/Hib vaccine + MMR vaccine (n = 68) | |

| Axillary temp of >37.5°C | 9 (8.3) | 28 (26.9) | 13 (19.1) |

| Decreased feeding | 27 (25.0) | 36 (34.6) | 20 (29.4) |

| Less active | 17 (15.7) | 26 (25.0) | 20 (29.4) |

| Increased irritability | 39 (36.1) | 46 (44.2) | 35 (51.5) |

| Persistent crying | 19 (17.6) | 23 (22.1) | 20 (29.4) |

| Vomiting | 13 (12.0) | 14 (13.5) | 12 (17.6) |

| Diarrhea | 24 (22.2) | 21 (20.2) | 12 (17.6) |

DISCUSSION

This study has shown no adverse consequences for either immunogenicity or reactogenicity when MCC/Hib vaccine was given concomitantly with PCV7 and MMR vaccine at 12 months compared with the separate administration of the two conjugate vaccines at 12 and 13 months of age, respectively.

Local reactions were generally mild, with the majority of children having no erythema, swelling, or tenderness at the site of administration of any vaccine, whether given concomitantly or sequentially. For the solicited systemic symptoms, there was no evidence of an additive effect; rather, any differences between schedules showed benefit from the concomitant administration of all three vaccines, such as lower overall proportions with postvaccination fevers. Given that the peak incidence of febrile convulsions is at around 12 months of age, any potentiation of a pyrexial response caused by concomitant administration of all three vaccines would have been concerning.

The lack of any adverse consequences of concomitant administration on the antibody responses to MCC, Hib, any of the seven PCV7 serotypes, diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, and measles, mumps, or rubella virus provides further evidence against the “immune overload” hypothesis (11, 15). Any small differences in immunogenicity were largely in the direction of a higher response when all three vaccines were given concomitantly.

For PCV7, the interval between doses in the priming schedule was shown not to affect the magnitude of the booster response (6). In the group of infants on the 2/3-month schedule who received a third dose between 145 and 331 days of age, 12 provided blood samples 4 weeks after this extra dose. Serotype-specific IgG responses after this extra dose were significantly lower than when the third dose was given at 12 or 13 months of age. This age dependency may have accounted for the slightly lower GMCs for six of the seven serotypes when PCV7 was given at 12 months with MCC/Hib vaccine than when it was administered separately at 13 months of age (Fig. 2).

The booster response to MCC/Hib vaccine was 2.1-fold higher in infants primed with MCC-TT than in those primed with MCC-CRM, though the postprimary response to MCC-TT was not higher (14). This finding is consistent with the higher booster response to MCC/Hib vaccine reported in infants primed with three doses of MCC/Hib-TT vaccine than in those primed with MCC-CRM (12), confirming that MCC-TT induces better priming than MCC-CRM (5). The effect of the magnitude of the postbooster SBA and Hib antibody levels on antibody persistence to 3 years of age has been reported separately (1). The finding that those children who failed to achieve protective levels of antibody to Hib also had significantly lower meningococcal serogroup C SBA, Hib, pneumococcal serotype 6B and 23F, diphtheria toxoid, and tetanus toxoid IgG levels postbooster has previously been reported for Hib, diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, and pertussis toxoid but had not been investigated to date for meningococcal serogroup C SBAs or pneumococcal serotype-specific IgG (7). It suggests that some otherwise healthy children have a generally lower antibody response to vaccine, and possibly other antigens, the clinical relevance of which is unknown.

Administration of both tetanus toxoid- and CRM-based conjugates in the second year of life was shown to boost tetanus and diphtheria toxoid IgG levels, with around 10-fold and 7-fold increases, respectively, in GMCs. This is of use for countries such as the United Kingdom where no DTaP booster dose is given in the second year of life.

Based on these data, it was recommended in the United Kingdom that the vaccines currently given at 12 and 13 months of age can be given at the same visit, between 12 and 13 months of age, within a month after the first birthday, to simplify the routine childhood immunization schedule (3).

Acknowledgments

This is an independent report funded by the Policy Research Programme in the Department of Health, United Kingdom, grant 039/031.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health.

We thank the vaccine research nurses in Hertfordshire and Gloucestershire for their contribution to the field work for this study and Teresa Gibbs and Deborah Cohen for administration of the trial.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borrow, R., et al. 2010. Kinetics of antibody persistence following administration of a combination meningococcal serogroup C and Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine in healthy infants in the United Kingdom primed with a monovalent meningococcal serogroup C vaccine. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17:154-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chief Medical Officer, Chief Nursing Officer, and Chief Pharmacist, Department of Health, London, United Kingdom. 2006. Important changes to the childhood immunisation programme. Professional letters PL/CMO/2006/1, PL/CNO/2006/1, and PL/CPHO/2006/1. Department of Health, London, United Kingdom.

- 3.Chief Medical Officer, Chief Nursing Officer, and Chief Pharmacist, Department of Health, London, United Kingdom. 2010. Vaccinations at 12 and 13 months of age. Professional letters PL/CMO/2010/3, PL/CNO/2010/4, and PL/CPHO/2010/2. Department of Health, London, United Kingdom.

- 4.Dhiman, N., et al. 2010. Detection of IgG-class antibodies to measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella-zoster virus using a multiplex bead immunoassay. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 67:346-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Díez-Domingo J., et al. 2010. A randomized, multicenter, open-label clinical trial to assess the immunogenicity of a meningococcal C vaccine booster dose administered to children aged 14 to 18 months. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 29:148-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldblatt, D., et al. 2010. Immunogenicity of a reduced schedule of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy infants and correlates of protection for serotype 6B in the United Kingdom. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 29:401-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldblatt, D., P. Richmond, E. Millard, C. Thornton, and E. Miller. 1999. The induction of immunologic memory after vaccination with Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate and acellular pertussis-containing diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine combination. J. Infect. Dis. 180:538-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maslanka, S. E., et al. 1997. Standardization and a multilaboratory comparison of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A and C serum bactericidal assays. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:156-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melville-Smith, M., and A. Balfour. 1988. Estimation of Corynebacterium diphtheriae antitoxin in human sera: a comparison of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with the toxin neutralisation test. J. Med. Microbiol. 25:279-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melville-Smith, M. E., V. A. Seagroatt, and J. T. Watkins. 1983. A comparison of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with the toxin neutralization test in mice as a method for the estimation of tetanus antitoxin in human sera. J. Biol. Standard. 11:137-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller, E., N. Andrews, P. Waight, and B. Taylor. 2003. Bacterial infections, immune overload, and MMR vaccine. Measles, mumps, and rubella. Arch. Dis. Child. 88:222-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pace, D., et al. 2008. A novel combined Hib-MenC-TT glycoconjugate vaccine as a booster dose for toddlers: a phase 3 open randomised controlled trial. Arch. Dis. Child. 93:963-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phipps, D. C., et al. 1990. An ELISA employing a Haemophilus influenzae type b oligosaccharide-human serum albumin conjugate correlates with the radioantigen binding assay. J. Immunol. Methods 135:121-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Southern, J., et al. 2009. Immunogenicity of a reduced schedule of meningococcal group C conjugate vaccine given concomitantly with a 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and a combination DTaP5/Hib/IPV vaccine in healthy UK infants. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:194-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stowe, J., N. Andrews, B. Taylor, and E. Miller. 2009. No evidence of an increase of bacterial or viral infections following measles, mumps and rubella vaccine. Vaccine 27:1422-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Pneumococcal Serology Reference Laboratories and Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham. 2007. Training manual for enzyme linked immunosorbent assay for quantification of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype specific IgG (Pn PS ELISA). World Health Organization Pneumococcal Serology Reference Laboratories at the Institute of Child Health, University College London, London, England, and Department of Pathology, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL. http://www.vaccine.uab.edu/ELISA%20Protocol.pdf.