Abstract

Much remains to be understood about how a group of cells break symmetry and differentiate into distinct cell types. The simple eukaryote Dictyostelium discoideum is an excellent model system for studying questions such as cell type differentiation. Dictyostelium cells grow as single cells. When the cells starve, they aggregate to develop into a multicellular structure with only two main cell types: spore and stalk. There has been a longstanding controversy as to how a cell makes the initial choice of becoming a spore or stalk cell. In this review, we describe how the controversy arose and how a consensus developed around a model in which initial cell type choice in Dictyostelium is dependent on the cell cycle phase that a cell happens to be in at the time that it starves.

A central question in developmental biology is how cells from the same lineage can differentiate into different cell types (61). Early experiments, for instance, transplanting pieces of endoderm onto different types of mesoderm, showed that signals from one type of mesoderm might cause the endoderm to become a certain cell type, while signals from another type of mesoderm might cause the same endoderm to become a totally different cell type (22). This, however, did not explain how an early lineage initially broke symmetry and differentiated into endoderm and mesoderm, or into different types of mesoderm. Some of the first work on true symmetry breaking, done by observing early cell divisions in nematode embryos, showed that asymmetric cell division is a simple and elegant differentiation mechanism. Another way to break symmetry was found by observing yeast mating type switching, where a genetic cassette is exchanged at some point in the cell cycle (71). There are other potential ways to generate different cell types (12, 49, 76), and an example of a third type of a symmetry-breaking differentiation mechanism was found by observing the development of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum.

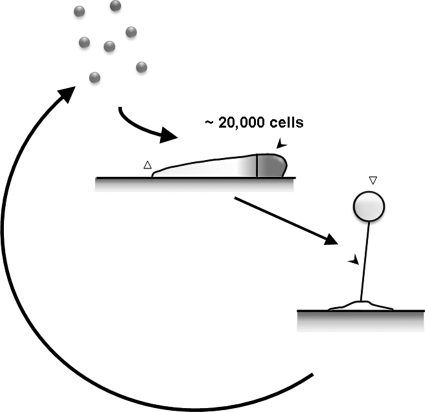

Dictyostelium is a soil amoeba that feeds on bacteria (for a review, see references 45 and 51. When food sources are ample, the amoebae grow as single cells. Upon starvation, cells begin a remarkable cooperation to disperse some of the population to new areas of soil (Fig. 1). First, as each cell starves, it begins to secrete conditioned medium factor (CMF) to signal that it is starving (16, 17, 26, 32, 33, 90, 91). Some of the starving cells start emitting cyclic AMP (cAMP) periodically, and when the local concentration of CMF reaches a threshold level, indicating that a majority of cells in the population are starving, cells become sensitive to cAMP (for a review, see references 28, 37, 63, 79, and 84). Using cAMP as a chemoattractant, cells form aggregation streams and flow into an aggregation center to form groups of ∼2 × 104 cells (for a review, see references 45 and 51. Each group of cells forms a worm-like 1- to 2-mm-long slug, which crawls toward the soil surface. At the surface, the slug then rearranges itself to form a fruiting body consisting of a mass of spore cells held up off the ground by a thin column of dead stalk cells. So a developing Dictyostelium cell has two potential fates: to become a prestalk (presumptive stalk) cell and die or to become a prespore (presumptive spore) cell and have a chance at forming a new colony.

Fig. 1.

The life cycle of Dictyostelium discoideum. Dictyostelium cells grow as a single-cell amoeba when there are ample nutrients. When starved, they aggregate, form a migrating slug made up of ∼20,000 cells, and undergo morphogenesis to form a multicellular fruiting body made up of a spore mass held off the soil by a thin column of stalk cells. The morphogen gradient model argues that the anterior region of a slug accumulates a higher concentration of DIF-1 (black arrowhead in slug), which causes the cells in the vicinity to become prestalk cells. Prestalk cells then become stalk cells (black arrowhead) in the fruiting body. Cells at the posterior of a slug (open arrowhead) become prespore cells, which become spores (open arrowhead) in the fruiting body.

THE CONTROVERSY

For many years, there was a controversy over how Dictyostelium cells choose to become a prestalk or a prespore cell, and the controversy became somewhat heated (87). One camp argued that there is a morphogen gradient in aggregates (Fig. 1) and that cells use the local concentration of the morphogen to choose their initial fate (38, 44, 47, 60, 87). A compelling candidate for such a morphogen was found and designated differentiation-inducing factor (DIF) (38). The other group argued that the initial cell type choice occurs earlier and is dependent on the cell cycle phase that the cell happens to be in at the time of starvation (4, 25, 58, 62, 82, 93). There are several markers for distinguishing prestalk cells and prespore cells, and the differences in the two proposed mechanisms may have been due to the fact that different groups used different prestalk markers.

IDENTIFYING CELL TYPES: PRESPORE MARKERS

At the slug stage, prestalk and prespore cells are essentially indistinguishable by phase-contrast microscopy, so determining whether a given cell is prestalk or prespore is done by staining cells (8, 72). Prespore cells can be identified by staining with antibodies raised against spore cells or using an expression construct where a prespore promoter drives expression of a marker such as β-galactosidase, and there has been general agreement in the field with respect to these prespore markers (18, 24, 27, 73). In slugs, these markers showed that prespore cells are located in the middle and posterior regions.

IDENTIFYING CELL TYPES: NEUTRAL RED STAINING

Essentially three different ways have been used to identify prestalk cells, and the interpretation of these three different marker methods has in part led to the controversies in our understanding of the initial cell type differentiation mechanism used by Dictyostelium cells. The first marker used to identify prestalk cells was staining with the vital dye neutral red. When slugs are stained with neutral red, cells in the anterior tip concentrate the dye more intensely than do prespore cells (8). However, the staining is relatively weak, and it is difficult to identify staining in individual cells.

IDENTIFYING CELL TYPES: ecm GENE EXPRESSION

In 1989, the Williams group used promoter regions to drive expression of β-galactosidase and found two promoter regions that cause the β-galactosidase to be expressed in the anterior tips of slugs (36, 88). Because these genes (now called ecmA and ecmB) are expressed in different regions of the anterior tip, this allowed the identification of different prestalk subtypes called prestalk-O (pstO), prestalk-A (pstA), prestalk-B (pstB), and prestalk-AB (pstAB) (for a review, see references 45 and 55).

IDENTIFYING CELL TYPES: STAINING FOR THE CP2 ANTIGEN

In 1986, the Firtel lab showed that antibodies raised against part of the open reading frame encompassed by the prestalk cathepsin (pst-cathepsin) gene (now called CP2) stained cells at the anterior tip of the slug (24). The beginning of the controversy started with CP2. Some groups argued that the CP2 mRNA is only marginally enriched in prestalk cells and thus cannot be used as a reliable marker for prestalk cells (35, 85). However, Mehdy and colleagues (59) showed that the CP2 mRNA is strongly enriched in prestalk cells, and β-glucuronidase expressed under the control of the CP2 promoter was observed only in the prestalk region of slugs (15). Clay and colleagues suggested that the antigen detected by staining with anti-CP2 antibodies is a viable marker for at least some prestalk cells (14). Using the expression patterns of CP2 and ecmA::β-galactosidase, they showed that expression of the CP2 antigen increases sharply at ∼8 h of starvation and the number of CP2-positive cells reaches a plateau around ∼10 h of starvation, whereas some ecmA::β-galactosidase-positive cells first appear at 16 h of starvation and the number of the positive cells steadily increases until 20 h of starvation. The ecmA::β-galactosidase-positive cells first appear as a subset of the CP2-positive cells, becoming a larger and larger subset. After 20 h of development, some CP2-negative cells then start expressing ecmA::β-galactosidase. This suggests that CP2 may be an early lineage marker for a subset of the ecmA::β-galactosidase-positive prestalk cells.

NULL CELLS

In Dictyostelium slugs and fruiting bodies, there are some cells that are not stained by either anti-CP2 or antiprespore (anti-SP70) antibodies (24). These cells are called null cells. In migrating slugs, null cells are mainly located in a region between the anterior (prestalk) and the posterior (prespore) region and also appear to be intermixed among the CP2-positive and the SP70-positive cells. Analysis of dissociated slugs showed that roughly 40% of the cells are null (25).

MORPHOGEN GRADIENT-DEPENDENT DIFFERENTIATION

One hypothesis regarding initial cell type choice in Dictyostelium was that the initial differentiation of prestalk and prespore cells is controlled by the concentration of a morphogen in the vicinity of a cell (19, 31, 42). One set of proposed morphogens, DIFs, are a set of chlorinated alkyl phenones which are dialyzable, lipid-like, and secreted by cells (31, 43, 77, 78). DIFs were identified as signal molecules which can induce isolated cells to differentiate into stalk cells in the presence of cyclic AMP (78). Among the different DIFs, DIF-1 [1-(3,5-dichloro-2,6-dihydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)hexan-1-one] is the main substance found in a purified DIF complex produced by prespore cells. DIF rapidly induces the expression of a subset of prestalk genes and represses the expression of all tested prespore genes (7, 11, 20, 21, 38–40, 43, 60, 86). DIF promotes differentiation of isolated amoebae into stalk cells and inhibits spore formation (44). Mutants (HM44 cells) that are impaired in DIF accumulation are able to form only prespore cells (46). The HM44 cells are unable to make stalk cells in vitro and during normal development on agar, and this condition can be rescued by the addition of exogenous DIF.

Observing that a secreted factor (DIF) potentiates stalk cell formation and represses spore formation thus suggested that DIF might be part of a morphogen gradient that determines initial cell type choice, with cells that happen to be in a region of the aggregate containing high levels of extracellular DIF becoming prestalk cells, and cells in a region that contains low levels of DIF becoming prespore cells. However, there were at least two problems with this model. First, it was found that prespore cells tend to produce DIF, and that the highest levels of DIF are found in the posterior region of the slug (11), where the prespore cells are located, contradicting the hypothesis that high levels of DIF cause cells to become prestalk. Second, mutants lacking DIF still differentiate into prestalk and prespore cells (69, 70). DmtA methyltransferase is an enzyme that carries out the last step of DIF synthesis (75). In dmtA− mutants, both prespore and pstA cells appear, and the mutants form roughly normal fruiting bodies. However, pstO cells do not appear in the dmtA− mutants, suggesting that there are either multiple signaling molecules or different mechanisms for the induction of pstO and pstA cells (41, 65, 75), which agrees with the observations that mutants that do not accumulate DIF-1 still produce both prestalk and prespore cells (69, 70). Saito et al. showed that DIF-1 is required to induce the basal disc, which is made up of pstO cells, and that DIF-1 is also partially required for formation of the lower cup, which is a mixed population of prestalk cells (65). In the absence of DIF-1, 30 to 40% fewer stalk cells were formed, suggesting that other prestalk cells can be formed without being exposed to DIF-1. In support of the idea that some aspects of Dictyostelium cell differentiation do not require DIF, it was found that some prestalk markers require DIF for expression (ecmA and ecmB), while other markers such as CP2, cAR2, and TagB do not require DIF for expression (65, 67, 68). Together, it appears that DIF-1 is required only for the differentiation of a subset of prestalk cells and that it is not a master control morphogen for stalk cell differentiation, suggesting that other factors are involved in cell type determination (52, 65, 89).

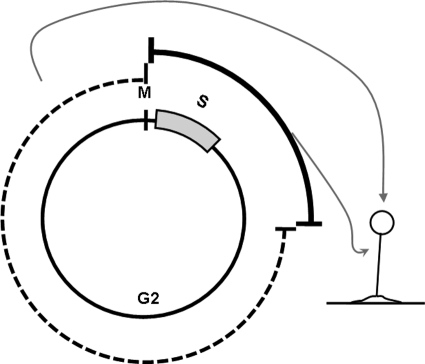

CELL CYCLE PHASE-DEPENDENT DIFFERENTIATION

As described below, several experiments suggested that the phase of the cell cycle that a cell happened to be in at the time of starvation could influence initial cell type choice (Fig. 2) (4, 5, 13, 23, 25, 57, 62, 83, 93). Dictyostelium cells growing in liquid culture have an ∼8-h cell cycle with, as in some fungi, no detectable G1 phase (83). Therefore, most cells are in the G2 phase of the cell cycle, since S phase and M phase take only ∼40 min to complete (45, 92).

Fig. 2.

The cell cycle-dependent model of initial cell type choice in Dictyostelium. The cell cycle-dependent model argues that the vegetative cells make an initial cell type choice depending on the phase of the cell cycle that they happen to be in at the time of starvation. If a pair of sister cells happen to be in S and early G2 phase (bold line) when they starve, they initially become a null cell and a CP2-positive prestalk cell. If a pair of sister cells happen to be in late G2 phase (dashed line) when they starve, they become a null cell and a prespore cell. The null cells then become prestalk or prespore cells depending on positional signals or other factors.

In the first experiments that indicated that cell cycle phase affects initial cell type choice, cells were synchronized so that most of the cells in the population were at the same phase of the cell cycle. The cells were then labeled with dyes and mixed with unlabeled unsynchronized cells and allowed to develop. Cells in S and early G2 phase at the time of starvation sort out to the anterior regions of developing Dictyostelium slugs and become predominantly prestalk cells, whereas cells in late G2 phase at the time of starvation sort out to posterior regions and become predominantly prespore cells (4, 54, 62). Other workers starved cells in S or early G2 phase to show that the resulting slugs have unusually high percentages of prestalk cells (80, 82). Videomicroscopy using cells grown in a low-density submerged culture, and then starved, showed that cells that are in either the middle or the late G2 phase of the cell cycle at the time of starvation tend to form prespore cells, whereas cells in early G2, S, or M phases tend to become CP2-positive cells (25). Under these conditions, the cells were many cell diameters apart from each other while they were proliferating and developing, and the observations of prespore and CP2-positive cells randomly distributed in the field suggested that cells under essentially identical extracellular conditions could still differentiate in the absence of a morphogen gradient. This experiment also allowed an examination of the lineage of cells and showed that for each cell that was either prespore (SP70 positive) or CP2 positive, the sister cell became a null cell. Null cells sometimes differentiated into prespore cells when they came in contact with other cells, suggesting that cell-cell interactions affect the eventual fate of the null cells (25, 26).

Reinforcing the idea that the phase of the cell cycle that a cell happens to be in at the time of starvation affects the initial cell type choice, it was observed that cells differ in their intrinsic sensitivities to DIF-1 according to their position in the cell cycle at the time of starvation (74). This then suggests that cell cycle phase affects cell type choice before DIF-1-induced differentiation (41, 74).

POSSIBLE CELL CYCLE-DEPENDENT CELL TYPE CHOICE MECHANISMS IN OTHER SYSTEMS

Similar cell cycle phase-dependent mechanisms have subsequently been observed in other systems (3, 34, 64). The Notch signaling pathway plays an important role in the determination of cell fate in many systems. In Caenorhabditis elegans vulva formation, Notch signaling occurs only during S phase (3). Cell cycle phase-dependent Notch signaling was also observed in asymmetric cell division during Drosophila melanogaster neurogenesis (3). In the formation of Drosophila bristles, cells are more prone to respond to Notch signaling during S phase (64). These results indicate that cell cycle phase may influence cell type choice in multiple systems.

CELL CYCLE PHASE-DEPENDENT DIFFERENTIATION AND CELL PHYSIOLOGY

Two physiological parameters, intracellular pH and calcium levels, have been linked to cell cycle-dependent initial cell type choice in Dictyostelium. In 1988, Gross and colleagues found that intracellular pH regulates differentiation (30). Using inhibitors of the plasma membrane proton pump to decrease the pH of intracellular vesicles, they were able to shift differentiation from the spore to the stalk pathway. Other researchers also found that cell cycle-dependent initial cell type choice is associated with intravesicular pH and cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations (6, 9, 10, 66). Starving Dictyostelium cells in high-Ca2+ medium induces stalk formation and inhibits spore formation (53). In addition, preaggregation and postaggregation Dictyostelium cells are heterogeneous with respect to Ca2+ levels, and cells that contain low Ca2+ levels have a prespore tendency while cells that contain high Ca2+ levels have a prestalk tendency (56, 66). Finally, cells in S and early G2 phase have relatively high levels of cellular Ca2+ and tend to differentiate into prestalk cells, and cells in mid- to late G2 phase have low Ca2+ levels and tend to differentiate into prespore cells (5).

Cytosolic pH also appears to vary during the cell cycle (29, 48, 81). Cells in M and S phases have a high cytosolic pH and have a prestalk tendency, whereas cells in mid- to late G2 phase have a low pH and a prespore tendency (2). In addition, starvation of cells in buffers with different pHs alters cell fate in accordance with the predicted cell fates (1, 2). Brazill et al. examined a mutant (rtoA−) with a randomized cell cycle-dependent cell type choice mechanism (prestalk and prespore cells originate from all phases of the cell cycle) and found that cytosolic pH is also randomized in rtoA− cells (9). This suggests the possibility that during evolution, an ancestor of Dicyostelium may have originally used a stochastic mechanism, possibly based on stochastic variations in cytosolic pH, to choose the initial cell type and that RtoA evolved to connect this mechanism to the cell cycle, so that the larger cells with more nutrient reserves (cells in late G2) would become prespore and the smaller cells with fewer nutrient reserves (cells that had just emerged from a cell division) would tend to become prestalk. Together, the data suggest that cell cycle-dependent changes in cytosolic or vesicular Ca2+ and/or pH may be a part of the cell cycle-dependent initial cell type choice mechanism.

CONCLUSION

The controversy surrounding the mechanism for initial cell type choice in Dictyostelium was likely caused by incomplete knowledge of the intricacies of prestalk subpopulations and by there not being enough markers to track those subpopulations in time and space. The expression of the ecm markers is dependent on DIF, and this then supported the idea that DIF regulates prestalk differentiation. Once prestalk markers that did not depend on DIF for their expression were discovered, the complexity of prestalk differentiation became apparent.

In Dictyostelium, the final (as opposed to the initial) cell type choice seems to involve both cell signaling and intrinsic biases present in the original growing cells (25, 50, 74). As with cells in many different organisms, Dictyostelium cell differentiation is not completely irreversible. The fate of at least some Dictyostelium cells during development is conditionally specified, meaning that cells can reversibly differentiate in response to external stimuli (for a review, see references 22, 45, 51, and 55). However, even if the fate of some cells in an organism during development is conditionally specified, it does not mean that every cell in the organism is conditionally specified, suggesting that there is room for autonomous specification. Together, these observations suggest that initial cell type choice can begin with cell-autonomous decisions which are later reinforced by a morphogen gradient-dependent mechanism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jonathan Phillips for helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by the Dongguk University research fund of 2006 (DRIMS 2006-1094-Z).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aerts R. J., Durston A. J., Konijn T. M. 1987. Cytoplasmic pH at the onset of development in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Sci. 87:423–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aerts R. J., Durston A. J., Moolenaar W. H. 1985. Cytoplasmic pH and the regulation of the Dictyostelium cell cycle. Cell 43:653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ambros V. 1999. Cell cycle-dependent sequencing of cell fate decisions in Caenorhabditis elegans vulva precursor cells. Development 126:1947–1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Araki T., Nakao H., Takeuchi I., Maeda Y. 1994. Cell-cycle-dependent sorting in the development of Dictyostelium cells. Dev. Biol. 162:221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Azhar M., et al. 2001. Cell cycle phase, cellular Ca2+ and development in Dictyostelium discoideum. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 45:405–414 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Azhar M., Kennady P., Pande G., Nanjundiah V. 1997. Stimulation by DIF causes an increase of intracellular Ca2+ in Dictyostelium discoideum. Exp. Cell Res. 230:403–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berks M., Kay R. R. 1990. Combinatorial control of cell differentiation by cAMP and DIF-1 during development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Development 110:977–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bonner J. T. 1952. The pattern of differentiation in ameboid slime molds. Am. Nat. 86:79–89 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brazill D. T., et al. 2000. A protein containing a serine-rich domain with vesicle-fusing properties mediates cell-cycle dependent cytosolic pH regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:19231–19240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brazill D. T., Meyer L., Hatton R. D., Brock D. A., Gomer R. H. 2001. ABC transporters required for endocytosis and endosomal pH regulation in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Sci. 114:3923–3932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brookman J. J., Jermyn K. A., Kay R. R. 1987. Nature and distribution of the morphogen DIF in the Dictyostelium slug. Development 100:119–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cagan R. 2009. Principles of Drosophila eye differentiation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 89:115–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen Y., Rodrick V., Yan Y., Brazill D. 2005. PldB, a putative phospholipase D homologue in Dictyostelium discoideum mediates quorum sensing during development. Eukaryot. Cell 4:694–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clay J. L., Ammann R. A., Gomer R. H. 1995. Initial cell type choice in a simple eukaryote: cell-autonomous or morphogen-gradient dependent? Dev. Biol. 172:665–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Datta S., Gomer R. H., Firtel R. A. 1986. Spatial and temporal regulation of a foreign gene by a prestalk-specific promotor in transformed Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6:811–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deery W. J., Gao T., Ammann R., Gomer R. H. 2002. A single cell-density sensing factor stimulates distinct signal transduction pathways through two different receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 277:31972–31979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deery W. J., Gomer R. H. 1999. A putative receptor mediating cell-density sensing in Dictyostelium. J. Biol. Chem. 274:34476–34482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dingermann T., et al. 1989. Optimization and in situ detection of Escherichia coli B-galactosidase gene expression in Dictyostelium discoideum. Gene 85:353–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Early A., Abe T., Williams J. 1995. Evidence for positional differentiation of prestalk cells and for a morphogenetic gradient in Dictyostelium. Cell 83:91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Early V. E., Williams J. G. 1988. A Dictyostelium prespore-specific gene is transcriptionally repressed by DIF in vitro. Development 103:519–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fosnaugh K. L., Loomis W. F. 1991. Coordinate regulation of the spore coat genes in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev. Genet. 12:123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gilbert S. C. 2006. Developmental biology. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gomer R., Ammann R. 1996. A cell-cycle phase-associated cell-type choice mechanism monitors the cell cycle rather than using an independent timer. Dev. Biol. 174:82–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gomer R. H., Datta S., Firtel R. A. 1986. Cellular and subcellular distribution of a cAMP-regulated prestalk protein and prespore protein in Dictyostelium discoideum: a study on the ontogeny of prestalk and prespore cells. J. Cell Biol. 103:1999–2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gomer R. H., Firtel R. A. 1987. Cell-autonomous determination of cell-type choice in Dictyostelium development by cell-cycle phase. Science 237:758–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gomer R. H., Yuen I. S., Firtel R. A. 1991. A secreted 80x103 Mr protein mediates sensing of cell density and the onset of development in Dictyostelium. Development 112:269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gregg J. H., Krefft M., Haas-Kraus A., Williams K. L. 1982. Antigenic differences detected between prespore cells of Dictyostelium discoideum and Dictyostelium mucuroides using monoclonal antibodies. Exp. Cell Res. 142:229–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gregor T., Fujimoto K., Masaki N., Sawai S. 2010. The onset of collective behavior in social amoebae. Science 328:1021–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gross J. D., Bradbury J., Kay R. R., Peacey M. J. 1983. Intracellular pH and the control of cell differentiation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature 303:244–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gross J. D., Peacey M. J., Pogge von Strandmann R. 1988. Plasma membrane proton pump inhibition and stalk cell differentiation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Differentiation 38:91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gross J. D., et al. 1981. Cell patterning in Dictyostelium. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 295:497–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jain R. 1994. Ph.D. dissertation. Rice University, Houston, TX [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jain R., Yuen I. S., Taphouse C. R., Gomer R. H. 1992. A density-sensing factor controls development in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 6:390–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. 2001. Asymmetric cell division in the Drosophila nervous system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2:772–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jermyn K. A., Berks M., Kay R. R., Williams J. G. 1987. Two distinct classes of prestalk-enriched mRNA sequences in Dictyostelium discoideum. Development 100:745–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jermyn K. A., Duffy K. T., Williams J. G. 1989. A new anatomy of the prestalk zone in Dictyostelium. Nature 340:144–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jin T., Hereld D. 2006. Moving toward understanding eukaryotic chemotaxis. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 85:905–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kay R. R. 1982. cAMP and spore differentiation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79:3228–3231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kay R. R. 1989. Evidence that elevated intracellular cyclic AMP triggers spore maturation in Dictyostelium. Development 105:753–759 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kay R. R. 1997. DIF signalling, p. 279–292 In Maeda Y., Inouye K., Takeuchi I. (ed.), Dictyostelium—a model system for cell and developmental biology. Universal Academy Press, Tokyo, Japan [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kay R. R. 2002. Chemotaxis and cell differentiation in Dictyostelium. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:575–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kay R. R., Berks M., Traynor D. 1989. Morphogen hunting in Dictyostelium. Development (Suppl.) 107:81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kay R. R., Dhokia B., Jermyn K. A. 1983. Purification of stalk-cell-inducing morphogens from Dictyostelium discoideum. Eur. J. Biochem. 136:51–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kay R. R., Jermyn K. A. 1983. A possible morphogen controlling differentiation in Dictyostelium. Nature 303:242–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kessin R. H. 2001. Dictyostelium—evolution, cell biology, and the development of multicellularity. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kopachik W., Oochata W., Dhokia B., Brookman J. J., Kay R. R. 1983. Dictyostelium mutants lacking DIF, a putative morphogen. Cell 33:397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Krefft M., Voet L., Gregg J. H., Mairhofer H., Williams K. L. 1984. Evidence that positional information is used to establish the prestalk-prespore pattern in Dictyostelium discoideum aggregates. EMBO J. 3:201–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kubohara Y., Okamoto K. 1994. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ and H+ concentrations determine cell fate in Dictyostelium discoideum. FASEB J. 8:869–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kutejova E., Briscoe J., Kicheva A. 2009. Temporal dynamics of patterning by morphogen gradients. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19:315–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Leach C. K., Ashworth J. M., Garrod D. R. 1973. Cell sorting out during the differentiation of mixtures of metabolically distinct populations of Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 29:647–661 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Loomis W. F. 1975. Dictyostelium discoideum: a developmental system. Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 52. Maeda M., et al. 2003. Changing patterns of gene expression in Dictyostelium prestalk cell subtypes recognized by in situ hybridization with genes from microarray analyses. Eukaryot. Cell 2:627–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Maeda Y. 1970. Influence of ionic conditions on cell differentiation and morphogenesis of the cellular slime molds. Dev. Growth Differ. 12:217–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maeda Y. 1997. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of the transition from growth to differentiation in Dictyostelium cells, p. 207–218 In Maeda Y., Inouye K., Takeuchi I. (ed.), Dictyostelium—a model system for cell and developmental biology. Universal Academy Press, Tokyo, Japan [Google Scholar]

- 55. Maeda Y., Inouye K., Takeuchi I. (ed.). 1997. Dictyostelium—a model system for cell and developmental biology. Universal Academy Press, Tokyo, Japan [Google Scholar]

- 56. Maeda Y., Maeda M. 1973. The calcium content of the cellular slime mold, Dictyostelium discoideum, during development and differentiation. Exp. Cell Res. 82:125–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. McDonald S. A. 1984. Developmental age-related cell sorting in Dictyostelium discoideum. Roux Arch. Dev. Biol. 194:50–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. McDonald S. A., Durston A. J. 1984. The cell cycle and sorting behaviour in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Cell Sci. 66:195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mehdy M. C., Ratner D., Firtel R. A. 1983. Induction and modulation of cell-type specific gene expression in Dictyostelium. Cell 32:763–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Morris H. R., Taylor G. W., Masento M. S., Jermyn K. A., Kay R. R. 1987. Chemical structure of the morphogen differentiation inducing factor from Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature 328:811–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Neumüller R. A., Knoblich J. A. 2009. Dividing cellular asymmetry: asymmetric cell division and its implications for stem cells and cancer. Genes Dev. 23:2675–2699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ohmori R., Maeda Y. 1987. The developmental fate of Dictyostelium discoideum cells depends greatly on the cell-cycle position at the onset of starvation. Cell Differ. 22:11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Parent C. A., Devreotes P. N. 1999. A cell's sense of direction. Science 284:765–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Remaud S., Audibert A., Gho M. 2008. S-phase favours notch cell responsiveness in the Drosophila bristle lineage. PLoS One 3:e3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Saito T., Kato A., Kay R. R. 2008. DIF-1 induces the basal disc of the Dictyostelium fruiting body. Dev. Biol. 317:444–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saran S., Azhar M., Manogaran P. S., Pande G., Nanjundiah V. 1994. The level of sequestered calcium in vegetative amoebae of Dictyostelium discoideum can predict post-aggregative cell fate. Differentiation 57:163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Saxe C. L., III, Yu Y. M., Jones C., Bauman A., Haynes C. 1996. The cAMP receptor subtype cAR2 is restricted to a subset of prestalk cells during Dictyostelium development and displays unexpected DIF-1 responsiveness. Dev. Biol. 174:202–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Shaulsky G., Escalante R., Loomis W. F. 1996. Developmental signal transduction pathways uncovered by genetic suppressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:15260–15265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shaulsky G., Kuspa A., Loomis W. F. 1995. A multidrug resistance transporter/serine protease gene is required for prestalk specialization in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 9:1111–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shaulsky G., Loomis W. F. 1996. Initial cell type divergence in Dictyostelium is independent of DIF-1. Dev. Biol. 174:214–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Strathern J. N., Herskowitz I. 1979. Asymmetry and directionality in production of new cell types during clonal growth: the switching pattern of homothallic yeast. Cell 17:371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Takeuchi I. 1963. Immunochemical and immunohistochemical studies on the development of the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium mucoroides. Dev. Biol. 8:1–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tasaka M., Noce T., Takeuchi I. 1983. Prestalk and prespore differentiation in Dictyostelium as detected by cell type-specific monoclonal antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 80:5340–5344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Thompson C., Kay R. 2000. Cell-fate choice in Dictyostelium: intrinsic biases modulate sensitivity to DIF signaling. Dev. Biol. 227:56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Thompson C., Kay R. 2000. The role of DIF-1 signaling in Dictyostelium development. Mol. Cell 6:1509–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Towers M., Tickle C. 2009. Generation of pattern and form in the developing limb. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 53:805–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Town C., Stanford E. 1979. An oligosaccharide-containing factor that induces cell differentiation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76:308–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Town C. D., Gross J. D., Kay R. R. 1976. Cell differentiation without morphogenesis in Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature 262:717–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Van Haastert P. J., Veltman D. M. 2007. Chemotaxis: navigating by multiple signaling pathways. Sci. STKE 2007:pe40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wang M., Aerts R. J., Spek W., Schaap P. 1988. Cell cycle phase in Dictyostelium discoideum is correlated with the expression of cyclic AMP production, detection, and degradation. Dev. Biol. 125:410–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wang M., Roelfsema J. H., Williams J. G., Schaap P. 1990. Cytoplasmic acidification facilitates but does not mediate DIF-induced prestalk gene expression in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev. Biol. 140:182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Weijer C. J., Duschl G., David C. N. 1984. Dependence of cell-type proportioning and sorting on cell cycle phase in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Cell Sci. 70:133–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Weijer C. J., Duschl G., David C. N. 1984. A revision of the Dictyostelium discoideum cell cycle. J. Cell Sci. 70:111–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Willard S. S., Devreotes P. N. 2006. Signaling pathways mediating chemotaxis in the social amoeba, Dictyostelium discoideum. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 85:897–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Williams J. 1997. Prestalk and stalk heterogeneity in Dictyostelium, p. 293–304 In Maeda Y., Inouye K., Takeuchi I. (ed.), Dictyostelium—a model system for cell and developmental biology. Universal Academy Press, Tokyo, Japan [Google Scholar]

- 86. Williams J. G., et al. 1987. Direct induction of Dictyostelium prestalk gene expression by DIF provides evidence that DIF is a morphogen. Cell 49:185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Williams J. G., et al. 1989. Origins of the prestalk-prespore pattern in Dictyostelium development. Cell 59:1157–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Williams J. G., Jermyn K. A., Duffy K. T. 1989. Formation and anatomy of the prestalk zone of Dictyostelium. Development 107(Suppl.):91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Yamada Y., Sakamoto H., Ogihara S., Maeda M. 2005. Novel patterns of the gene expression regulation in the prestalk region along the antero-posterior axis during multicellular development of Dictyostelium. Gene Expr. Patterns 6:63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Yuen I. S., Gomer R. H. 1994. Cell density-sensing in Dictyostelium by means of the accumulation rate, diffusion coefficient and activity threshold of a protein secreted by starved cells. J. Theor. Biol. 167:273–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yuen I. S., et al. 1995. A density-sensing factor regulates signal transduction in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Biol. 129:1251–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Zada-Hames I. M., Ashworth J. M. 1978. The cell cycle and its relationship to development in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev. Biol. 63:307–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Zimmerman W., Weijer C. J. 1993. Analysis of cell cycle progression during the development of Dictyostelium and its relationship to differentiation. Dev. Biol. 160:178–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]