Abstract

Candida glabrata is an opportunistic human pathogen that is increasingly associated with candidemia, owing in part to the intrinsic and acquired high tolerance the organism exhibits for the important clinical antifungal drug fluconazole. This elevated fluconazole resistance often develops through gain-of-function mutations in the zinc cluster-containing transcriptional regulator C. glabrata Pdr1 (CgPdr1). CgPdr1 induces the expression of an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter-encoding gene, CgCDR1. Saccharomyces cerevisiae has two CgPdr1 homologues called ScPdr1 and ScPdr3. These factors control the expression of an ABC transporter-encoding gene called ScPDR5, which encodes a homologue of CgCDR1. Loss of the mitochondrial genome (ρ0 cell) or overexpression of the mitochondrial enzyme ScPsd1 induces ScPDR5 expression in a strictly ScPdr3-dependent fashion. ScPdr3 requires the presence of a transcriptional Mediator subunit called Gal11 (Med15) to fully induce ScPDR5 transcription in response to ρ0 signaling. ScPdr1 does not respond to either ρ0 signals or ScPsd1 overproduction. In this study, we employed transcriptional fusions between CgPdr1 target promoters, like CgCDR1, to demonstrate that CgPdr1 stimulates gene expression via binding to elements called pleiotropic drug response elements (PDREs). Deletion mapping and electrophoretic mobility shift assays demonstrated that a single PDRE in the CgCDR1 promoter was capable of supporting ρ0-induced gene expression. Removal of one of the two ScGal11 homologues from C. glabrata caused a major defect in drug-induced expression of CgCDR1 but had a quantitatively minor effect on ρ0-stimulated transcription. These data demonstrate that CgPdr1 appears to combine features of ScPdr1 and ScPdr3 to produce a transcription factor with chimeric regulatory properties.

One of the major clinical complications arising from infections caused by the pathogenic yeast Candida glabrata is the high-frequency acquisition of azole resistance (3, 26, 27). Since azole drugs are the principal chemotherapy used against these fungal infections, loss of drug efficacy is an impediment to the eventual clearing of the organism by the patient. An additional difficulty associated with the azole resistance phenotype in C. glabrata comes from the common observation that fluconazole (the most commonly employed azole drug)-resistant C. glabrata cells also exhibit tolerance for other azoles (25, 26, 29). This multiazole tolerance phenotype is most commonly associated with activation of the expression of an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter-encoding gene called C. glabrata CDR1 (CgCDR1) by a Zn2Cys6 zinc cluster-containing transcription factor called CgPdr1 (37, 38). This enhanced production of CgCdr1 protein leads to increased efflux of antifungal drugs from these resistant strains.

Prior to the discovery of the CgPdr1-CgCDR1 transcriptional circuit, an analogous regulatory axis was described in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Substitution mutations within the S. cerevisiae PDR1 (ScPDR1) coding sequence produced S. cerevisiae cells exhibiting profound resistance to a wide range of different drugs (reviewed in references 1, 11, and 40). Later work showed that much of this drug resistance was due to activation of an ABC transporter-encoding gene called ScPDR5 (2, 4, 15). Subsequently, the ScPDR3 locus was found to encode a zinc cluster protein that acted similarly to ScPdr1 and could also be altered at a single amino acid position to produce a hyperactive transcriptional regulator (24, 32). Target genes for both ScPdr1 and ScPdr3 were found to contain an element related to a 8-bp consensus sequence referred to as the pleiotropic drug response element (PDRE) (TCCGCGGA) (17). Experiments probing the regulation of ScPdr1 and ScPdr3 indicated that the two factors were controlled in different ways. Overproduction of an Hsp70 protein now called Ssz1 induced ScPdr1 activity but had no effect on ScPdr3 (13). Conversely, loss of the mitochondrial genome (ρ0 cells) or overproduction of the mitochondrial enzyme phosphatidylserine decarboxylase (ScPsd1) enhanced ScPdr3 activity but had no influence on ScPdr1 (12, 14, 36). Several laboratories have demonstrated that ρ0 C. glabrata cells also exhibit elevated CgPdr1-dependent gene expression (10, 37, 38), suggesting that CgPdr1 regulation might more closely resemble that of ScPdr3.

In the current work, we investigate several features of the action of CgPdr1 in C. glabrata directly. A Renilla reniformis luciferase (RLUC) gene fusion was used to demonstrate that the promoter regions from two CgPdr1-responsive genes, as well as CgPDR1 itself, are sufficient to recapitulate CgPdr1 signaling. Deletion mapping of a CgCDR1-RLUC fusion gene indicated that a single PDRE, detected initially by sequence conservation with its S. cerevisiae cognate element, was sufficient to provide CgPdr1 responsiveness. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) and DNase I footprinting determined that recombinant CgPdr1 was able to bind directly to a PDRE. Previous experiments provided evidence that loss of the transcriptional Mediator subunit CgGal11A caused a decrease in drug-induced CgCDR1 expression in ρ+ cells (35). Overproduction of CgPsd1 was found to increase fluconazole resistance in a CgCDR1- and CgPdr1-dependent manner, directly analogous to the effect in S. cerevisiae (12). These experiments indicate that CgPdr1 shares many regulatory properties with ScPdr3, even though it shares more sequence identity with ScPdr1 (37, 38). We suggest that CgPdr1 behaves as a chimera of ScPdr1 and ScPdr3 in C. glabrata.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and spot test assay.

The C. glabrata strains used for this study are listed in Table 1. Yeast cells were grown on rich YPD (2% yeast extract, 1% peptone, 2% glucose) medium or on synthetic complete medium lacking appropriate auxotrophic components (31). All ρ0 strains used in this study were generated by growing the corresponding ρ+ strain on YPD plates containing 25 μg/ml ethidium bromide. The ρ0 state was confirmed by inability to grow in a nonfermentable carbon source, such as YPGE (2% yeast extract, 1% peptone, 3% glycerol, 3% ethanol), as well as by a lack of mitochondrial nucleoids, as revealed by DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining. Yeast strains were transformed by the lithium acetate method (16). Drug resistance was measured by the spot test assay on plates by growing mid-log-phase cells at 37°C with the appropriate concentration of drug.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Derivation | Relevant genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40F1 | Cgura3Δ(−85 +932)::Tn903 NeoR | Cgura3 | David Soll |

| 40F1 ρ0 | Cgura3Δ(−85 +932)::Tn903 NeoR ρ0 | Cgura3 ρ0 | This study |

| JSS3 | 40F1 CgHO::pJS24::CgHO | Cg CDR1-RLUC | This study |

| JSS4 | 40F1 CgHO::pJS25::CgHO | Cg CDR2-RLUC | This study |

| JSS5 | 40F1 CgHO::pH 12.7::CgHO | Promoterless RLUC | This study |

| JSS6 | JSS3 ρ0 | Cg CDR1-RLUC ρ0 | This study |

| JSS7 | JSS4 ρ0 | Cg CDR2-RLUC ρ0 | This study |

| JSS8 | JSS5 ρ0 | Promoterless RLUC ρ0 | This study |

| JSS9 | 40F1 gal11BΔ::HphR | gal11BΔ | This study |

| JSS10 | 40F1 gal11AΔ::HphR | gal11AΔ | This study |

| JSS11 | JSS9 CgHO::pJS24::CgHO | gal11BΔ CgCDR1-RLUC | This study |

| JSS12 | JSS9 CgHO::pJS25::CgHO | gal11BΔ CgCDR2-RLUC | This study |

| JSS14 | JSS10 CgHO::pJS24::CgHO | gal11AΔ CgCDR1-RLUC | This study |

| JSS15 | JSS10 CgHO::pJS25::CgHO | gal11AΔ CgCDR2-RLUC | This study |

| JSS20 | JSS9 CgPSD1::pJS13::CgPSD1 | CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| JSS21 | JSS9 CgPGK1::pJS20::CgPGK1 | CgPGK1 promoter-CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| JSS22 | JSS10 CgPSD1::pJS13::CgPSD1 | CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| JSS23 | JSS10 CgPGK1::pJS20::CgPGK1 | CgPGK1 promoter-CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| JSS24 | 40F1 cdr1Δ::natMX | Cgcdr1Δ | This study |

| JSS25 | 40F1 pdr1Δ::natMX | Cgpdr1Δ | This study |

| JSS26 | 40F1 cdr2Δ::natMX | Cgcdr2Δ | This study |

| JSS28 | JSS24 ρ0 | Cgcdr1Δ ρ0 | This study |

| JSS29 | JSS25 ρ0 | Cgpdr1Δ ρ0 | This study |

| JSS30 | 40F1 CgHO::pJS53::CgHO | CgPDR1-RLUC | This study |

| JSS31 | 40F1 CgHO::pJS50::CgHO | −407 CgCDR1-RLUC with PDRE 5 | This study |

| JSS33 | 40F1 CgHO::pJS51::CgHO | −364 CgCDR1-RLUC with no PDRE | This study |

| JSS34 | JSS30 ρ0 | CgPDR1-RLUC ρ0 | This study |

| JSS35 | JSS31 ρ0 | −407 CgCDR1-RLUC with PDRE 5 ρ0 | This study |

| JSS37 | JSS33 ρ0 | −364 CgCDR1-RLUC with no PDRE ρ0 | This study |

| SPG1 | 40F1 CgGAL11B::pJS27::CgGAL11B | CgGAL11B-13× Myc | This study |

| SPG3 | 40F1 CgGAL11A::pJS28::CgGAL11A | CgGAL11A-13× Myc | This study |

| SPG5 | 40F1 ρ0 CgGAL11B::pJS27::CgGAL11B | CgGAL11B-13× Myc ρ0 | This study |

| SPG7 | 40F1 ρ0 CgGAL11A::pJS28::CgGAL11A | CgGAL11A-13× Myc ρ0 | This study |

| SPG9 | JSS9 ρ0 | Cggal11BΔ ρ0 | This study |

| SPG13 | JSS10 ρ0 | Cggal11AΔ ρ0 | This study |

| SPG17 | JSS11 ρ0 | Cggal11BΔ CgCDR1-RLUC ρ0 | This study |

| SPG19 | JSS12 ρ0 | Cggal11BΔ CgCDR2-RLUC ρ0 | This study |

| SPG23 | JSS14 ρ0 | Cggal11AΔ CgCDR1-RLUC ρ0 | This study |

| SPG25 | JSS15 ρ0 | Cggal11AΔ CgCDR2-RLUC ρ0 | This study |

| SPG29 | JSS25 | Cgpdr1Δ CgPDR1-RLUC | This study |

| SPG31 | JSS25 | Cgpdr1Δ CgCDR1-RLUC | This study |

| SPG33 | JSS25 | Cgpdr1Δ CgCDR2-RLUC | This study |

| SPG37 | SPG29 ρ0 | Cgpdr1Δ CgPDR1-RLUC ρ0 | This study |

| SPG39 | SPG31 ρ0 | Cgpdr1Δ CgCDR1-RLUC ρ0 | This study |

| SPG41 | SPG33 ρ0 | Cgpdr1Δ CgCDR2-RLUC ρ0 | This study |

| SPG53 | 40F1 CgPSD1::pJS13::CgPSD1 | CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| SPG55 | 40F1 CgPGK1::pJS20::CgPGK1 | CgPGK1 promoter-CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| SPG57 | JSS24 CgPSD1::pJS13::CgPSD1 | Cgcdr1Δ CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| SPG59 | JSS24 CgPGK1::pJS20::CgPGK1 | Cgcdr1Δ CgPGK1 promoter-CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| SPG60 | JSS25 CgPSD1::pJS13::CgPSD1 | Cgpdr1Δ CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| SPG63 | JSS25 CgPGK1::pJS20::CgPGK1 | Cgpdr1Δ CgPGK1 promoter-CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| SPG65 | JSS26 CgPSD1::pJS13::CgPSD1 | Cgcdr2Δ CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| SPG67 | JSS26 CgPGK1::pJS20::CgPGK1 | Cgcdr2Δ CgPGK1 promoter-CgPSD1-HA | This study |

Plasmids.

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. All promoter constructs used for generating reporter gene (RLUC) transcriptional fusions were prepared as PCR products with appropriate primers and then cloned in the pCR2.1-TOPO TA cloning vector. These clones were verified by DNA sequencing and then digested with PstI and inserted into the pH12.7 vector (34) linearized with PstI, which cuts just upstream of the R. reniformis luciferase coding sequence. The correct orientation of the promoter was confirmed by restriction mapping and sequencing. Plasmids with promoter-reporter gene transcriptional fusions were linearized by Bsu36I and targeted to the CgHO gene locus by homologous recombination, as described previously (34). Targeted and single-copy integrations were confirmed by PCR of upstream and downstream novel junctions generated by recombination, as well as by Southern blotting. For Myc tagging, the CgGAL11B and CgGAL11A genes, along with 200 bp of noncoding DNA flanking each end of the coding sequences, were PCR amplified and cloned into the pYES2.1 expression vector to form pJS16 and pJS17, respectively. The 13× Myc tag was amplified from plasmid pFA6a-13Myc-kanMX6 (21) and inserted at the C-terminus of each Gal11 homologue by recombinational cloning in S. cerevisiae under G418 selection. Targeted integration of these plasmids was achieved at the respective CgGAL11 loci by linearizing pJS27 and pJS28 by SalI and KpnI digestion, respectively.

Table 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pH 12.7 | ScURA3 Renilla luciferase fusion vector | 34 |

| pJS13 | pRS426 2μm ScURA3 ScPSD1 promoter-CgPSD1-HA | 12 |

| pJS16 | pYES2.1 CgGAL11B | This study |

| pJS17 | pYES2.1 CgGAL11A | This study |

| pJS20 | pRS426 2μm URA3 CgPGK1 promoter-CgPSD1-HA | This study |

| pJS24 | pH 12.7 CgCDR1 promoter | This study |

| pJS25 | pH 12.7 CgCDR2 promoter | This study |

| pJS27 | pYES2.1 CgGAL11B-13× Myc G418r | This study |

| pJS28 | pYES2.1 CgGAL11A-13× Myc G418r | This study |

| pJS50 | pH 12.7 CgCDR1 promoter with PDRE 5 | This study |

| pJS51 | pH 12.7 CgCDR1 promoter with no PDRE | This study |

| pJS53 | pH 12.7 CgPDR1 promoter | This study |

CgPsd1 was C-terminally hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged by amplification of C. glabrata PSD1 from 40F1 genomic DNA and insertion into the pJS6 (12) plasmid carrying the S. cerevisiae PSD1 promoter and a C-terminal HA tag by recombinational cloning in S. cerevisiae. This produced pJS13, consisting of the ScPSD1 promoter driving production of CgPsd1-HA. Genomic integration of pJS13 was achieved by linearizing the plasmid by HpaI digestion. For overexpression of CgPSD1, the C. glabrata PGK1 promoter was amplified from genomic DNA and cloned into pJS13 with BamHI and NotI digestion to generate pJS20. Genomic integration of pJS20 was achieved by linearizing the plasmid by AvrII digestion, which directs recombination to the CgPGK1 locus.

Luciferase assay.

The Renilla luciferase assay was performed using the Renilla Luciferase Assay Kit (from Biotium, Inc.). Briefly, 2 ml of mid-log-phase cells was lysed using 200 μl of 1× Passive Lysis Buffer (Biotium, Inc.) by vortexing the cells for 4 min at 4°C in the presence of glass beads. The cells were centrifuged, and the cell lysate (supernatant) was collected; 5 μl of the cell lysate was added to 12.5 μl of Renilla Luciferase Assay Enhancer (Biotium, Inc.) and 12.5 μl of Renilla Luciferase Assay Solution (2× coelenterazine solution; Biotium, Inc.) in 96-well plates in triplicate. Luminescence was measured using the Ivis 100 Imaging System (Caliper Life Sciences). The number of photons emitted per second (luminescence) was then normalized to the amount of total protein present in the cell lysate per ml using a Bradford assay. The luciferase assay data depicted in this paper are from two independent experiments involving all luciferase reporter strains mentioned here.

Protein purification.

The predicted DNA binding domain of CgPDR1 (CgPDR1-DBD) was amplified from C. glabrata genomic DNA by PCR using the forward primer 5′-CGCGGATCCATGGAAACATTAGAAACTACATCAAAATC and the reverse primer 5′-CGCGTCGACTCTAGATCCTAAATCTTGTTAGATGAAC. The PCR product was cloned as a BamHI/SalI fragment into the pET28a+ vector and transformed into BL21(DE3) bacteria. One liter of transformed bacteria was grown to log phase and induced with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 90 min. Cell lysates were prepared using a French press. Purification was accomplished using Talon metal affinity resin as described by the manufacturer (Clonetech Laboratory, Inc.). Finally, protein was dialyzed overnight against buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 10% glycerol, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 10 mM ZnCl2, 50 mM NaCl). Protein fractions were analyzed by staining them with Coomassie blue.

EMSA.

CgCDR1 promoter fragments (200 bp long) containing a mutated or normal CgPDRE site 5 were amplified from the 40F1 strain by PCR and radiolabeled using T4 DNA kinase (New England Biolabs) and [γ-32P]ATP. The predicted CgCDR1 PDRE site 5 was altered from TCCACGGAA to TCCGTCGAC by PCR-based mutagenesis based on previous work that demonstrated ScPdr1 was unable to bind such a mutant PDRE (18). The wild-type or mutated PDREs were placed 19 bases downstream of the 5′ end of the forward primer. Radiolabeled DNA probes were purified using a Qiagen PCR purification kit. The radioactivity of the purified probes was measured using a scintillation counter, and equal amounts of radiolabeled DNA were added to the recombinant DNA binding domain of CgPdr1. The binding reaction was carried out in 4% glycerol, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 60 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 20 μg/ml poly(dI-dC) for 45 min at 30°C. DNA and protein-DNA complexes were resolved by electrophoresis at 160 V on a 4% native acrylamide gel at room temperature using a buffer containing 45 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 45 mM boric acid, and 1 mM EDTA. The gel was dried, exposed to X-ray film overnight at −80°C, and then visualized by autoradiography.

DNase I footprinting.

The DNase I template was prepared from a PCR product of the CgPDR1 promoter containing 748 to 504 bp upstream of the CgPDR1 translation start site with both the predicted PDREs. This region was amplified from the 40F1 strain using primers SalI-CgPDR1(−748)F (5′-GTCGACGTCCGTTTCCCGCAACC) and CgPDR1(−504)R (5′-ACGCAATACCTGCTTATCC) and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO. These plasmids were digested with BamHI, treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase, phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP, and finally cleaved with SalI. The labeled fragments were isolated from an agarose gel using a Qiagen mini-elute column. DNase I protection was performed as reported previously (23) using bacterially expressed CgPdr1-DBD.

Real-time PCR.

Quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR was performed as described in reference 30. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from each strain with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Synthesis of cDNA was performed using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) with 1 μg of RNA as a template. For the quantitative PCR, primers were designed using the Primer Select program from the DNAStar software package. Primer concentrations were optimized for each gene, and annealing profiles were analyzed to evaluate nonspecific amplification by primer dimers. Control reaction mixtures including RNA instead of cDNA were performed for each gene and condition. The threshold cycle (CT) values were determined in the logarithmic phase of amplification for all genes, and the average CT value for each sample was calculated from three replicates. The CT value of the gene coding for actin (CgACT1) was used for normalization of variable cDNA levels, and induction factors were determined for each gene and condition. Amplification was carried out in the iCycler apparatus from Bio-Rad in a two-step process as follows: a denaturation step of 3 min at 95°C and 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s each, with annealing and extension at 60°C for 45 s each. The reporter signals were analyzed using the iCycler iQ software (Bio-Rad).

Western blot analysis.

For Western analysis, cells were grown in 4 ml of YPD or selective medium. Protein extracts were made as follows. Cells were harvested at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼1.0, washed, and resuspended in 1 ml water. To this cell suspension, 150 μl of YEX buffer (1.85 M NaOH, 7.5% β-mercaptoethanol) was added, and the cells were vortexed and incubated in ice for 10 min. One hundred fifty microliters of 50% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was then added, and the cells were vortexed and incubated in ice for a further 10 min. The proteins were then pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 100 μl sample buffer (8 M urea, 1% mercaptoethanol, bromophenol blue, and 10% unbuffered Tris)/OD600 unit. The resuspended proteins were incubated in sample buffer for 15 min at 37°C and centrifuged, and 20 μl of the supernatant was separated using 10% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline, and then probed with anti-HA or anti-Myc antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and an ECL kit (Pierce) were used to visualize immunoreactive proteins.

RESULTS

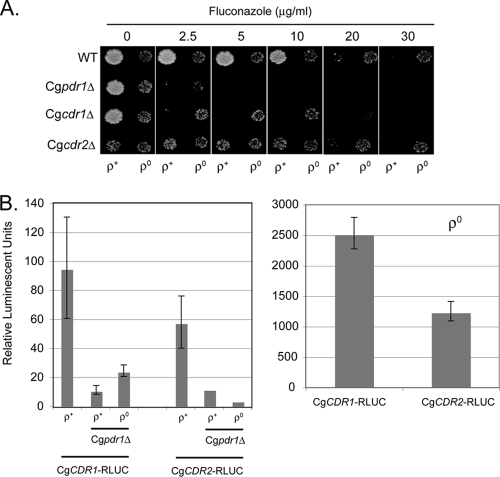

Previous work has demonstrated that C. glabrata cells lacking their mitochondrial genome (ρ0) exhibit high-level fluconazole resistance through increased expression levels of the major ABC transporter-encoding gene, CgCDR1 (6, 28). Later work discovered a transcription factor called CgPdr1 that is the major determinant of the transcription levels of CgCDR1 (37, 38). Together, these observations suggest that C. glabrata ρ0 cells may activate the function of CgPdr1, which in turn induces CgCDR1 transcription, resulting in high-level fluconazole resistance. A similar pathway has been characterized in S. cerevisiae by our group and others (14, 36). To confirm the presence of this common transcriptional control system in C. glabrata, we prepared isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 strains containing or lacking key drug resistance genes. This set of strains was then plated on rich medium containing various concentrations of fluconazole. The plates were photographed after incubation at 37°C (Fig. 1 A).

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic and reporter gene analysis of C. glabrata multidrug resistance genes. (A) Isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 C. glabrata strains lacking the indicated genes were grown to mid-log phase and then placed on rich medium containing the indicated concentrations of fluconazole. The plates were incubated at 37°C and then photographed. WT, wild type. (B) The CgCDR1- and CgCDR2-RLUC fusion plasmids were integrated into isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 C. glabrata strains containing or lacking the CgPDR1 gene. Appropriate transformants were grown to mid-log phase and then assayed for luciferase activity using the coelenterazine substrate. The ρ0 transformants were plotted on a separate scale due to the high-level expression of the reporter genes. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

As reported by others, loss of the mitochondrial genome produced a strong fluconazole-resistant phenotype in the otherwise wild-type genetic background. Importantly, loss of the CgPDR1 gene dramatically reduced the fluconazole resistance of both the ρ+ and ρ0 isolates. As seen before, removal of the CgCDR1 ABC transporter-encoding gene also reduced the fluconazole tolerance of both ρ+ and ρ0 strains. In ρ0 cells, loss of CgPDR1 caused a greater reduction in fluconazole resistance than did loss of CgCDR1. Deletion of the CgCdr1 homologue-encoding CgCDR2 locus had no detectable effect on fluconazole resistance.

The transcriptional induction caused by loss of the mitochondrial genome has previously been shown at the level of steady-state mRNA (27). Our work in S. cerevisiae established that ρ0 cells induce expression of the CgCDR1 homologue ScPDR5 gene at the level of the promoter (14, 41). To determine if a similar mechanism occurred in C. glabrata, we constructed transcriptional fusion genes between the CgCDR1 and CgCDR2 promoters with RLUC (33, 34). These reporter genes were integrated into isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 strains containing or lacking the CgPDR1 gene. Single-copy integration was verified by Southern blotting, and appropriate transformants were grown in minimal medium to mid-log phase. Cell-free protein extracts were prepared, and luciferase enzyme activity was determined using the coelentrazine substrate, as described previously (33) (Fig. 1B).

Both the CgCDR1-RLUC and CgCDR2-RLUC fusion genes produced Renilla luciferase activity that was greatly increased in the absence of mitochondrial DNA. The ρ0 induction of these two fusion genes varied between 25- and 22-fold. Luciferase activity directed by the CgCDR1 promoter increased from 95 units/mg to 2,500 units/mg upon loss of the mitochondrial genome. Similarly, CgCDR2-RLUC produced 58 units/mg, which increased to 1,250 units/mg in ρ0 cells. Strikingly, loss of CgPDR1 strongly reduced the expression of both CgCDR1- and CgCDR2-RLUC fusion genes to 11 units/mg in ρ+ cells. There was no significant induction of either ABC transporter-encoding gene in ρ0 cells lacking CgPDR1. This result indicates that CgPdr1 is required for ρ0 induction of CgCDR1 and CgCDR2 but also may represent the major, if not sole, regulatory factor driving expression of these genes.

Functional mapping of a CgPdr1 binding site in the CgCDR1 promoter.

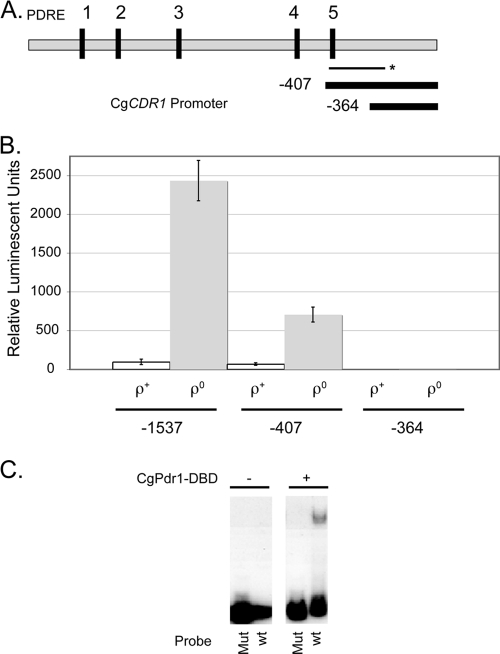

Work with S. cerevisiae has established the presence of binding sites for the homologous ScPdr1/ScPdr3 transcription factors in the promoters of genes involved in the pleiotropic drug response in the yeast (8, 17, 39). These elements are referred to as PDREs and correspond to a consensus sequence of TCCGYGGA (18). Inspection of the CgCDR1 5′ noncoding region led to the prediction of the presence of five TCCACGGA elements closely related to the S. cerevisiae PDRE. These PDREs are located at −379, −507, −961, −1192, and −1323 upstream of the CgCDR1 ATG codon (Fig. 2 A). While all these sites were retained in our original luciferase reporter construct, we wanted to determine if a single PDRE would be sufficient to maintain the CgPdr1-mediated response to loss of mitochondrial DNA, as we have done previously in S. cerevisiae (17). To accomplish this, two promoter truncation mutants were prepared. The first contained 407 bp of 5′ noncoding DNA, which includes the most promoter-proximal PDRE (referred to as PDRE site 5), while the second construct contained only 364 DNA of upstream DNA and lacked any discernible PDRE. These two versions of the CgCDR1 promoter were fused to the luciferase reporter gene and integrated into isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 cells, and the luciferase enzyme activity was measured.

Fig. 2.

Mapping the CgCDR1 promoter. (A) Diagram of the upstream −1,500 bp of the CgCDR1 promoter. The vertical solid lines indicate the predicted locations of PDREs. The two thick horizontal solid lines indicate the DNA contained in the two CgCDR1 promoter deletion constructs analyzed here. The −407 fragment contains the site 5 PDRE, while the −364 fragment does not. The thin line labeled with an asterisk indicates the bounds of the PCR fragment used in the EMSA described for panel B. (B) CgCDR1-RLUC fusion genes containing the indicated amounts of 5′ noncoding DNA were integrated into isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 C. glabrata strains. Transformants were assayed for luciferase activity as described for panel A. The error bars indicate standard deviations. (C) Two versions of the EMSA probe described above were prepared by PCR. They were either the wild-type (wt) form or a mutant (Mut) variant in which several base pairs in the putative PDRE were mutagenized. Both fragments were radiolabeled with 32P and used as a probe in an EMSA reaction. The purified recombinant CgPdr1 DBD fragment was either omitted (−) or included (+) in the binding reaction mixture. These reaction mixtures were then electrophoresed through a nondenaturing gel. The gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film.

Truncation of the CgCDR1 promoter from 1,537 bp of 5′ flanking DNA to only 407 bp reduced but did not eliminate the induction seen in ρ0 cells (Fig. 2B). The −407 construct still produced 10-fold induction of luciferase activity upon removal of mitochondrial DNA. This truncated promoter still produced 67 units/mg of luciferase activity compared to 95 units/mg in the case of the full-length CgCDR1-RLUC fusion. Extending the truncation mutation to −364 eliminated any response to ρ0 signaling and reduced the level of enzyme activity to approximately 1 unit/mg. These data support the view that the PDRE present at −379 in CgCDR1 can serve as a minimal CgPdr1-responsive promoter element. To confirm that this binding site can interact with CgPdr1, we carried out an EMSA with a DNA fragment containing or lacking the site.

To examine direct binding of CgPdr1 to the site 5 PDRE, we first prepared recombinant CgPdr1 by cloning a fragment corresponding to the amino-terminal 295 amino acids of the transcription factor into the Escherichia coli expression vector pET28a+. The protein was purified from E. coli by standard techniques. A 200-bp fragment of the CgCDR1 promoter (indicated in Fig. 2A) was prepared by PCR in two different forms. We used wild-type primers to prepare an unaltered version of this DNA region and a mutant primer pair to change the PDRE from TCCACCGA (wild type) to TCGTCGAC (mutant). Each PCR fragment was radiolabeled with 32P and mixed with control protein (BSA) or recombinant CgPdr1. After binding, complexes were separated by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis, and the location of the radiolabeled DNA was detected by autoradiography (Fig. 2C).

A CgPdr1-DNA complex was detected when the wild-type PDRE site 5-containing fragment was used as a probe but not when the site 5 mutant was employed. No complexes were seen when BSA was used as the input protein. Together, these data argue that CgPdr1 directly recognizes the PDREs upstream of the CgCDR1 gene and acts to regulate transcription from the gene.

The CgPDR1 gene is transcriptionally autoregulated through its promoter.

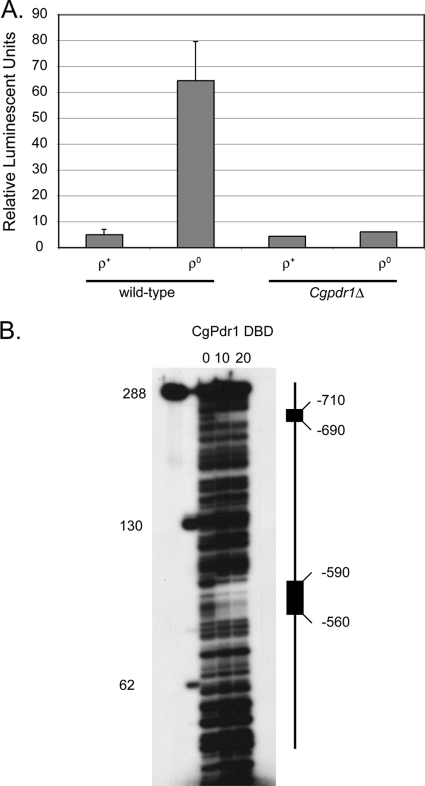

Measurements of CgPDR1 mRNA levels have suggested that this locus may be autoregulated in C. glabrata as ScPDR3 is in S. cerevisiae (8). Searching the CgPDR1 promoter for potential PDREs detected the presence of two likely TCCACGGA sequences located at −549 and −693 upstream of the CgPDR1 ATG codon. We constructed a luciferase reporter gene fusion between the CgPDR1 promoter and RLUC as described above for the analysis of the CgCDR1 gene. This CgPDR1-RLUC fusion gene was then integrated into isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 cells containing or lacking a wild-type copy of CgPDR1. Appropriate transformants were grown to mid-log phase and assayed for luciferase enzyme activity as before (Fig. 3 A).

Fig. 3.

Evidence for positive autoregulation of the CgPDR1 gene. (A) The CgPDR1-RLUC fusion gene was integrated into ρ+ and ρ0 strains containing or lacking the wild-type CgPDR1 gene. Transformants were assayed for luciferase activity as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) A fragment containing the two putative PDREs present in the CgPDR1 promoter was end labeled with 32P. This fragment was then incubated with the indicated volumes (in microliters) of bacterially expressed CgPdr1 DNA binding domain. After binding, the protein-DNA complexes were treated with DNase I as described previously (17). The digestion products were separated on a urea-polyacrylamide gel and detected by exposure to X-ray film. The radiolabeled fragment was untreated or digested separately with RsaI and BspMI restriction enzymes and electrophoresed in parallel to provide the size markers indicated on the left side of the autoradiogram. A graphic representation of the two protected regions is shown on the right, with the approximate position of each PDRE indicated.

The CgPDR1-RLUC gene was induced by roughly 10-fold upon loss of the mitochondrial genome. In ρ+ cells, the expression level of this fusion gene was only 5% the level of a similar fusion for CgCDR1, consistent with the CgPDR1 promoter driving expression of the transcriptional regulatory protein CgPdr1, while CgCDR1 produced the more abundant CgCdr1 ABC transporter. Strikingly, induction of the CgPDR1-RLUC fusion gene was eliminated upon deletion of the wild-type CgPDR1 gene, again supporting the proposal that CgPDR1 is positively autoregulated.

The dependence of CgPDR1-RLUC expression upon the presence of an intact copy of CgPDR1 was consistent with the idea that CgPdr1 controls its own expression. To test the ability of CgPdr1 to bind to the potential PDREs detected in the CgPDR1 promoter, we carried out a DNase I protection assay using a probe corresponding to the CgPDR1 5′ noncoding region. A probe containing both PDREs was uniquely end labeled with 32P and incubated with or without recombinant CgPdr1, and the resulting protein-DNA complexes were digested lightly with DNase I. The digestion products were then separated on an 8% polyacrylamide urea gel and visualized by autoradiography (Fig. 3B).

Both PDREs were protected from DNase I cleavage by the recombinant CgPdr1. Our data support the view that CgPdr1 controls its own expression through binding to two PDREs in its promoter and autoregulating the transcription levels of the gene. The transcriptional control of CgPDR1 more closely resembles that of ScPDR3 than that of its namesake, ScPDR1.

Differential role of CgGal11 homologues in fluconazole resistance and transcription in ρ0 cells.

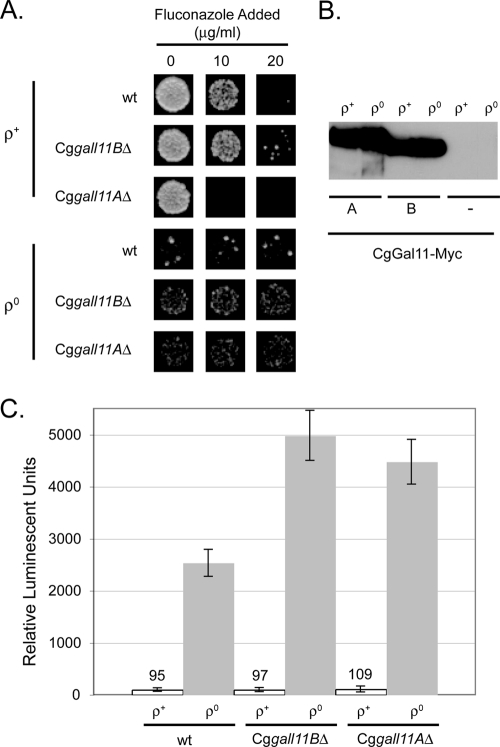

Previous work (35) has shown that CgPdr1 directly interacts with one of the two Gal11 homologues present in C. glabrata. Gal11 proteins (also known as Med15 [5]) are components of the transcriptional Mediator, a complex of proteins that often provides interfaces between RNA polymerase II and upstream activator proteins (reviewed in reference 7). C. glabrata contains two Gal11 homologues, one on chromosome 8 (CgGAL11A) and another on chromosome 6 (CgGAL11B). Our previous studies of S. cerevisiae have implicated the single Gal11 homologue present in the yeast as an important quantitative participant in ρ0-mediated activation of ScPDR5 transcription (30). To determine if these C. glabrata homologues played a similar role in ρ0 induction of CgCDR1-CgPDR1 transcription, isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 cells were constructed that lacked the CgGAL11 homologue on either chromosome 6 or chromosome 8. Appropriate disruption mutants were grown to mid-log phase and tested for the ability to grow in the presence of various concentrations of fluconazole (Fig. 4 A).

Fig. 4.

Roles of CgGal11 homologues in control of CgCDR1 in ρ+ and ρ0 cells. (A) Disruption alleles of CgGAL11A or CgGAL11B were transformed into isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 cells. Transformants were tested for the ability to grow in the presence of fluconazole as described previously. (B) Plasmids containing 13× Myc-tagged versions of either CgGAL11A (lanes A) or CgGAL11B (lanes B) were integrated in the wild-type versions of both genes into ρ+ and ρ0 C. glabrata strains. Correct transformants were grown to mid-log phase, and protein extracts were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies directed against the Myc epitope. Protein extracts from the untagged strains (−) were analyzed as a negative control for the presence of the Myc tag. (C) The strains in panels A and B were transformed with the CgCDR1-RLUC plasmid. The transformants were assayed for luciferase activity as before.

Loss of CgGAL11A, but not CgGAL11B, from ρ+ cells caused a large decrease in fluconazole resistance, as seen previously (35). Strikingly, neither CgGal11 homologue was required for the elevated fluconazole resistance seen in ρ0 cells. CgGAL11A is important in fluconazole resistance, but only in ρ+ cells, while CgGal11B does not appear to contribute to drug resistance.

The unequal contributions of the two CgGal11 proteins to fluconazole resistance could be explained by differential expression of these factors. To examine the levels of expression of the CgGal11 proteins, epitope-tagged versions of both genes were prepared in isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 strains. A 13× Myc epitope was fused to the C termini of both proteins. Appropriate transformants were grown to mid-log phase, and protein extracts were prepared and assessed by Western blotting for the expression of the CgGal11 proteins using anti-Myc antibodies (Fig. 4B).

The expression levels of the two CgGal11 proteins were identical in both ρ+ and ρ0 cells. The sizes predicted from the DNA sequences of these genes agreed well with the sizes of the epitope-tagged proteins detected in C. glabrata protein extracts. CgGal11B is predicted to be a protein of 838 amino acids with a molecular mass of 96 kDa. CgGal11A is larger, composed of 1,095 amino acids with a molecular mass of 121 kDa. Since both proteins were tagged with identical epitopes, their relative expression levels can also be compared from this experiment. These two Mediator components are expressed at similar levels, and phenotypic differences seen upon individual removal did not correlate with their relative expression levels.

The CgCDR1-RLUC reporter gene was also integrated into the same Cggal11Δ strains to examine the ability of the promoter region to respond to changes in the dosages of these Mediator components. Based on the fluconazole sensitivity of the Cggal11AΔ strain compared to the lack of influence of the Cggal11BΔ mutation, we expected a decrease in CgCDR1 expression in the Cggal11AΔ background. The reporter gene was integrated into isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 strains containing either both or only one of the two CgGAL11 genes. Appropriate transformants were then assayed for levels of luciferase enzyme activity (Fig. 4C).

Two surprising features were noted upon determination of CgCDR1-RLUC expression in these strains. First, no effect was seen on CgCDR1-dependent luciferase activity upon loss of CgGal11A from ρ+ cells. Additionally, removal of either CgGal11 protein caused a roughly 2-fold increase in CgCDR1-RLUC expression in ρ0 cells.

These data were unexpected, since the phenotypic assays described above indicated that loss of CgGal11A, but not CgGal11B, caused fluconazole sensitivity in ρ+ cells. To explore the reason underlying the lack of a selective effect of CgGal11A on CgCDR1 expression, we considered two possibilities. Since we used a gene fusion approach to measure expression, the defect caused by loss of CgGal11A might be exerted at another step of regulation, such as posttranscriptional control of CgCDR1 transcript. Experiments in C. albicans suggested that the stability of CaCDR1 mRNA may contribute to its ultimate level of expression in the pathogen (22). Since the reporter gene fusions encode chimeric C. glabrata-RLUC transcripts, posttranscriptional regulation may not be replicated in these constructs. Second, it is possible that the presence of fluconazole is required to detect the expected decreased expression caused specifically by loss of CgGal11A compared to removal of CgGal11B.

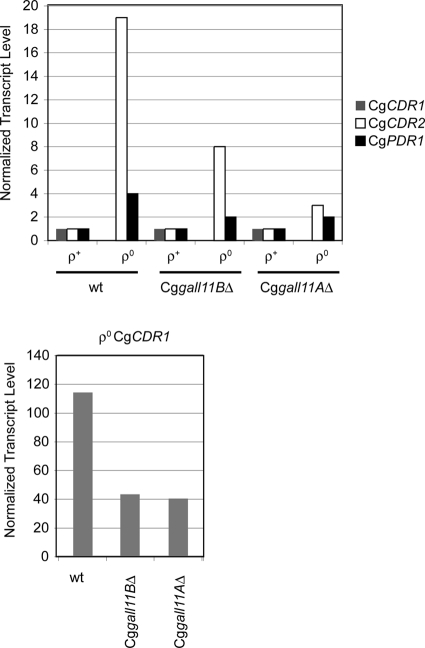

To compare the contribution of the CgGal11 homologues to transcriptional control of authentic genes involved in drug resistance, we used qRT-PCR analyses to measure expression of the chromosomal copies of CgCDR1, CgCDR2, and CgPDR1. Isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 strains containing either both or only one of the two CgGAL11 genes were grown to mid-log phase, total RNA was isolated, and mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Transcription profile of C. glabrata multidrug resistance gene transcripts. Isogenic ρ+ and ρ0 strains containing the indicated alleles of the CgGAL11 genes were grown to mid-log phase, and total RNA was isolated from each. Each RNA sample was assayed by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR analysis for the steady-state level of each indicated multidrug resistance gene. Each sample was assayed for CgACT1 and normalized to the level seen in ρ+ wild-type cells.

Assay of steady-state mRNA by qRT-PCR demonstrated that CgCDR1 transcription was highly induced, by more than 100-fold, upon loss of the mitochondrial genome. Loss of either CgGal11 homologue reduced this level of induction by approximately 50% but still supported at least a 40-fold response in ρ0 cells, indicating that strong induction remained in the absence of either Mediator subunit. CgCDR2 induction was 20-fold in ρ0 cells. This was reduced to 8-fold in ρ0 cells lacking CgGal11B and to only 3-fold in the ρ0 strain lacking CgGal11A deletion. Transcriptional induction of CgPDR1 was more modest, being elevated to roughly 4-fold upon loss of the mitochondrial genome. As with the ABC transporter-encoding genes, loss of either CgGal11 homologue reduced this induction by 50% (to 2-fold). Since loss of either CgGal11A or CgGal11B caused quantitatively similar levels of expression of authentic CgCDR1 mRNA, no uniquely important role for CgGal11A could be seen using this different assay for gene transcription.

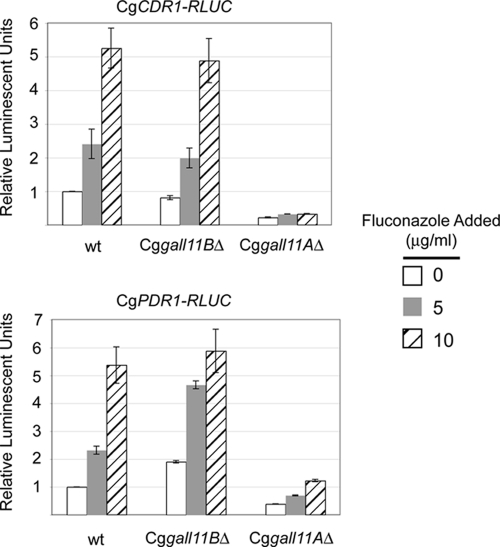

An obvious difference between the expression measurements above and the phenotypic analysis is the presence of the drug fluconazole. Loss of CgGal11A, but not CgGal11B, has previously been demonstrated by qRT-PCR to cause a reduction in CgCDR2 transcription (35). To evaluate if the CgCDR1-RLUC reporter would exhibit similar dependence on CgGal11A for drug-induced transcription, we challenged ρ+ cells containing or lacking CgGal11A or CgGal11B with fluconazole and then assayed luciferase levels. These same strains were also transformed with CgPDR1-RLUC and tested for fluconazole-induced luciferase levels (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Fluconazole induction of CgCDR1 and CgPDR1 expression requires CgGal11A. The RLUC fusion gene at the top of each panel was integrated into strains containing the indicated alleles of CgGAL11. Transformants were grown to early log phase, challenged with various concentrations of fluconazole in the medium, and then assayed for luciferase activity. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

As was seen for the wild-type transcripts, both CgCDR1 and CgPDR1 were induced upon treatment with fluconazole. Importantly, loss of CgGal11A caused a complete block of drug induction in the case of the CgCDR1-RLUC reporter. Fluconazole failed to normally induce CgPDR1-RLUC in the absence of CgGal11A. Loss of CgGal11B had no effect on fluconazole induction of either reporter gene. These data demonstrate that loss of CgGal11A blocks normal drug induction of CgCDR1 and CgPDR1 in the ρ+ background. Since this behavior can be recapitulated using a reporter gene containing only the promoter region of the two genes, this genetic determinant is sufficient to provide a significant component of fluconazole regulation. Additionally, the importance of CgGal11A for control of CgCDR1 transcription is uncovered during drug-induced, but not ρ0-activated, gene expression.

Overproduction of mitochondrial phosphatidylserine decarboxylase elevates fluconazole resistance.

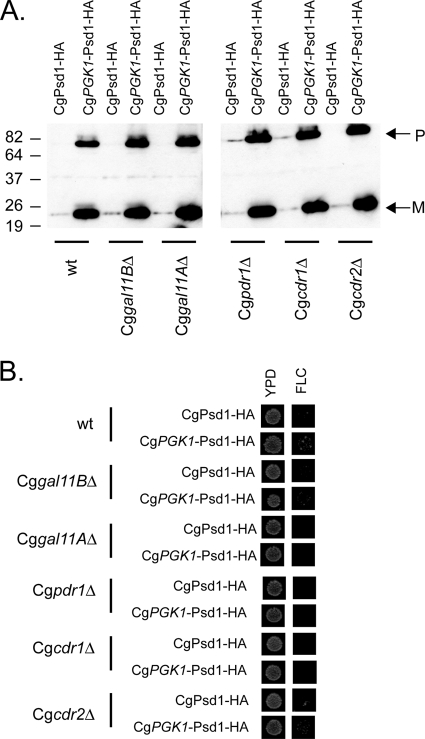

Our previous work in S. cerevisiae led to the identification of the mitochondrial phosphatidylserine decarboxylase ScPsd1 as an upstream positive regulator of the expression of the ABC transporter-encoding gene ScPDR5 (12). Interestingly, expression of CgPsd1 in S. cerevisiae cells also induced ScPDR5 expression. Since these experiments were performed only in the heterologous S. cerevisiae host, we wanted to determine if overproduction of CgPsd1 in C. glabrata cells would have a similar positive effect on drug resistance. To examine this possibility, we prepared an epitope-tagged version of the CgPSD1 gene containing a single HA tag at the C terminus of this locus. Two different versions of this epitope-tagged CgPSD1 allele were prepared. The first contained the ScPSD1 promoter driving production of the C. glabrata protein and was described previously (12). The second replaced the ScPSD1 promoter with the CgPGK1 promoter in order to drive overproduction of CgPsd1 using this strong glycolytic promoter. The plasmid containing the ScPSD1 promoter-driven CgPsd1-HA tag was integrated back into the wild-type CgPSD1 locus. The CgPGK1 promoter-driven CgPsd1-HA tag construct was targeted to integrate at the CgPGK1 locus. This strategy led to the production of two different strains expressing CgPsd1-HA from either the wild-type CgPSD1 promoter or the CgPGK1 promoter. To ensure that these strains produced the desired differences in CgPsd1-HA expression, appropriate transformants were grown to mid-log phase, and protein extracts were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibodies (Fig. 7 A).

Fig. 7.

Overexpression of CgPsd1 induces fluconazole resistance in C. glabrata. (A) Plasmids containing either the S. cerevisiae PSD1 promoter or the C. glabrata PGK1 promoter driving expression of a CgPsd1-HA fusion protein were integrated into the wild-type CgPSD1 gene or the CgPGK1 promoter, respectively. This single crossover led to production of a C. glabrata strain producing HA-tagged CgPsd1 under the control of the wild-type CgPSD1 promoter (CgPsd1-HA) or the CgPGK1 promoter (CgPGK1-Psd1-HA). Appropriate transformants were grown to mid-log phase and then analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HA antibodies. Molecular mass standards (kDa) are indicated on the left. P denotes the presence of the unprocessed precursor form of CgPsd1-HA, while M indicates the position of the processed C-terminal CgPsd1-HA fragment. (B) The plasmids described in the legend to panel A were integrated into the strains indicated. Desired transformants were tested for their relative growth on rich medium lacking (YPD) or containing (FLC) fluconazole.

The CgPGK1-Psd1-HA-containing strain led to a large increase in the production of two different immunoreactive species: a large protein of 78 kDa and a small protein of 24 kDa. Based on previous analyses (12, 19, 20), the larger species represents a precursor polypeptide, while the smaller fragment corresponds to mature CgPsd1-HA in which the C-terminal segment of the protein is autoproteolytically cleaved away from the rest of the enzyme. We previously described this processing of the CgPsd1-HA expressed in the S. cerevisiae environment (12). The increased levels of these proteins seen in the strain containing the CgPGK1 promoter expressing the CgPsd1-HA protein are consistent with the overproduction of the enzyme.

These two constructs were then transformed into several different mutant backgrounds to evaluate the genetics of CgPsd1-mediated activation of fluconazole resistance. Derivatives of the two CgGAL11 disruption mutants were generated, as well as Cgpdr1Δ, Cgcdr1Δ, and Cgcdr2Δ derivatives. We first verified that the expected expression of the integrated CgPsd1-HA proteins was detected to ensure that these mutants did not alter the overproduction phenotype observed in the otherwise wild-type genetic background. All these mutants exhibited the same overproduction of CgPsd1-HA seen when expressed from the CgPGK1 promoter (Fig. 7A). Next, these transformants were placed on fluconazole-containing medium to assess the level of azole resistance induced by CgPsd1-HA overproduction.

Elevated levels of CgPsd1-HA enhanced fluconazole tolerance in wild-type C. glabrata cells. However, overproduction of this mitochondrial enzyme failed to increase fluconazole resistance in cells lacking CgGal11A, CgPdr1, or CgCdr1. Loss of CgGal11B or CgCdr2 had no influence on CgPsd1-HA-induced fluconazole resistance.

Two important findings emerged from this experiment. First, CgPsd1-HA can act to enhance drug resistance in its native background, as this factor did when expressed in the heterologous S. cerevisiae host. Second, the regulatory pathway inferred from these data includes CgGal11A, CgPdr1, and CgCDR1, which is closely analogous to the ScGal11, ScPdr3, and ScPDR5 pathway in S. cerevisiae. These data support the idea that, while many of the components involved in regulation of drug resistance by the Psd1 enzyme are similar between C. glabrata and S. cerevisiae, important differences emerged and will be considered below.

DISCUSSION

Studies from a number of laboratories have already provided much information concerning the basic regulatory organization of multidrug resistance gene expression in C. glabrata. While the picture detailing changes in expression of important genes, like CgCDR1, at the level of the mRNA is clear, little is known of the molecular mechanisms underlying transcriptional control. Here, we demonstrated that much of the observed regulation of CgCDR1 by ρ0 signals can be recapitulated by a reporter construct containing only the promoter of the gene. This is very similar to the situation in S. cerevisiae and C. albicans. However, based on qRT-PCR analyses (Fig. 5), CgCDR1 may have a significant posttranscriptional regulatory component, as has been described for CaCDR1 (22).

The use of this reporter gene system allowed us to determine the minimally ρ0-responsive promoter for CgCDR1. This segment, consisting of 307 bp upstream of the translation start site, contains a single PDRE. Parallel behavior was seen during a similar analysis of the ScPDR5 promoter (17). While a single PDRE is sufficient for the ρ0-mediated induction of CgCDR1, full induction requires multiple PDREs, again similar to the situation in S. cerevisiae (41). The importance of CgPdr1 binding to these PDREs can be seen by consideration of the effect of a Cgpdr1Δ allele on fluconazole resistance, especially in ρ0 cells (Fig. 1A). The Cgpdr1Δ ρ0 strain exhibited profound fluconazole sensitivity that was even greater than that caused by a Cgcdr1Δ lesion in a ρ0 background. The simplest interpretation of these data is that the presence of either CgCdr1 or CgCdr2 is sufficient for normal fluconazole tolerance in ρ0 cells, although activation of both of these genes relies upon the presence of CgPdr1. Given the lack of a phenotypic consequence caused by loss of Cgcdr2 from ρ0 cells, it is also possible that CgPdr1 activates a gene other than CgCdr1 to influence fluconazole resistance. We are constructing a double Cgcdr1Δ Cgcdr2Δ ρ0 strain to discriminate between these two ideas.

Along with its unique importance as a quantitative determinant of multidrug resistance gene transcription, CgPdr1 is also regulated in a more complex fashion than either ScPdr1 or ScPdr3. These S. cerevisiae factors are individually responsive to different trans-regulators and upstream signals. ScPdr1 is induced by elevated expression of the Hsp70 protein Ssz1 (13) or the DnaJ protein Zuo1 (9), while ScPdr3 is not influenced by either of these chaperone proteins. Conversely, ScPdr3 is strongly induced in ρ0 cells, while ScPdr1 is insensitive to loss of mitochondrial DNA (14). As demonstrated here, CgPsd1 induction of fluconazole resistance proceeds through CgPdr1, while ScPdr1 does not respond to the signal induced by overproduction of this mitochondrial enzyme in S. cerevisiae (12). Finally, CgPDR1 and ScPDR3 share a positive autoregulatory loop that is absent from ScPDR1 (8, 38). CgPdr1 seems to be a blend of the regulatory properties of ScPdr1 and ScPdr3. While CgPdr1 and ScPdr1 share the highest degree of sequence similarity, as their names imply, the regulatory relationships so far examined indicate that CgPdr1 is responsive to signals that control ScPdr3.

Analysis of the interaction of CgGal11A and CgPdr1 during transcriptional activation also illustrates important differences between C. glabrata and S. cerevisiae. In S. cerevisiae, the single Gal11 homologue is required for full transcriptional activation by both ScPdr1 and ScPdr3 under all conditions tested (30, 35). This effect is easily seen in the ρ0-mediated activation of ScPDR5 by ScPdr3 (30). In the absence of ScGal11, ScPdr3 can still activate ScPDR5 expression, but to a level roughly 30% of that seen in ScGAL11 cells in both ρ+ and ρ0 cells. The experiments performed in the current study in C. glabrata indicate that CgGal11A is only required for drug-induced expression of CgCDR1. While a clear reduction in fluconazole resistance was seen upon loss of CgGal11A, CgCDR1 mRNA was still more than 40-fold induced in a ρ0 Cggal11AΔ strain and was not altered in a ρ+ Cggal11AΔ cell. However, we were able to detect a defect in fluconazole-mediated induction of both CgCDR1-RLUC and CgPDR1-RLUC when assayed in a ρ+ Cggal11AΔ strain.

These data detail an important difference in the behavior of drug- and ρ0-induced CgPdr1. CgGal11A is essential for normal gene activation during fluconazole challenge but is dispensable upon loss of the mitochondrial genome. This suggests that some other mediator component can replace CgGal11A action in ρ0 but not in ρ+ cells. This suggestion is also supported by the reduction in fluconazole resistance that was seen upon overproduction of CgPsd1 when CgGal11A was removed from this genetic background. Our data are consistent with the view that different mediator components are involved in CgPdr1-dependent transcription in ρ+ and ρ0 cells. This behavior is reminiscent of ScPdr3, which is highly dependent on the presence of Med12 (Srb8) in ρ0 cells but independent of the factor during activation of ScPDR5 in ρ+ cells (30). We have begun experiments to examine the role of CgMed12 in the control of CgCDR1 transcription.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant GM49825.

We thank Srikantha Thyagarajan and David Soll for plasmids and advice.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1. Balzi E., Goffeau A. 1991. Multiple or pleiotropic drug resistance in yeast. BBA 1073:241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balzi E., Wang M., Leterme S., Van Dyck L., Goffeau A. 1994. PDR5: a novel yeast multidrug resistance transporter controlled by the transcription regulator PDR1. J. Biol. Chem. 269:2206–2214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennett J. E., Izumikawa K., Marr K. A. 2004. Mechanism of increased fluconazole resistance in Candida glabrata during prophylaxis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1773–1777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bissinger P. H., Kuchler K. 1994. Molecular cloning and expression of the S. cerevisiae STS1 gene product. J. Biol. Chem. 269:4180–4186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bourbon H. M., et al. 2004. A unified nomenclature for protein subunits of mediator complexes linking transcriptional regulators to RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell 14:553–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brun S., et al. 2004. Mechanisms of azole resistance in petite mutants of Candida glabrata. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1788–1796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Casamassimi A., Napoli C. 2007. Mediator complexes and eukaryotic transcription regulation: an overview. Biochimie 89:1439–1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Delahodde A., Delaveau T., Jacq C. 1995. Positive autoregulation of the yeast transcription factor Pdr3p, involved in the control of the drug resistance phenomenon. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4043–4051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eisenman H. C., Craig E. A. 2004. Activation of pleiotropic drug resistance by the J-protein and Hsp70-related proteins, Zuo1 and Ssz1. Mol. Microbiol. 53:335–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferrari S., et al. 2009. Gain of function mutations in CgPDR1 of Candida glabrata not only mediate antifungal resistance but also enhance virulence. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gulshan K., Moye-Rowley W. S. 2007. Multidrug resistance in fungi. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1933–1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gulshan K., Schmidt J., Shahi P., Moye-Rowley W. S. 2008. Evidence for the bifunctional nature of mitochondrial phosphatidylserine decarboxylase: role in Pdr3-dependent retrograde regulation of PDR5 expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:5851–5864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hallstrom T. C., Katzmann D. J., Torres R. J., Sharp W. J., Moye-Rowley W. S. 1998. Regulation of transcription factor Pdr1p function by a Hsp70 protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:1147–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hallstrom T. C., Moye-Rowley W. S. 2000. Multiple signals from dysfunctional mitochondria activate the pleiotropic drug resistance pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisae. J. Biol. Chem. 275:37347–37356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hirata D., Yano K., Miyahara K., Miyakawa T. 1994. Saccharomyces cerevisiae YDR1, which encodes a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily, is required for multidrug resistance. Curr. Genet. 26:285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ito H., Fukuda Y., Murata K., Kimura A. 1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153:163–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Katzmann D. J., Burnett P. E., Golin J., Mahe Y., Moye-Rowley W. S. 1994. Transcriptional control of the yeast PDR5 gene by the PDR3 gene product. Mol. Cell Biol. 14:4653–4661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katzmann D. J., Hallstrom T. C., Mahe Y., Moye-Rowley W. S. 1996. Multiple Pdr1p/Pdr3p binding sites are essential for normal expression of the ATP binding cassette transporter protein-encoding gene PDR5. J. Biol. Chem. 271:23049–23054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuge O., Saito K., Kojima M., Akamatsu Y., Nishijima M. 1996. Post-translational processing of the phosphatidylserine decarboxylase gene product in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochem. J. 319:33–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li Q. X., Dowhan W. 1990. Studies on the mechanism of formation of the pyruvate prosthetic group of phosphatidylserine decarboxylase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 265:4111–4115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Longtine M. S., et al. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Manoharlal R., Gaur N. A., Panwar S. L., Morschhauser J., Prasad R. 2008. Transcriptional activation and increased mRNA stability contribute to overexpression of CDR1 in azole-resistant Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1481–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moye-Rowley W. S., Harshman K. D., Parker C. S. 1989. Yeast YAP1 encodes a novel form of the Jun family of transcriptional activator proteins. Genes Dev. 3:283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nourani A., Papajova D., Delahodde A., Jacq C., Subik J. 1997. Clustered amino acid substitutions in the yeast transcription regulator Pdr3p increase pleiotropic drug resistance and identify a new central regulatory domain. Mol. Gen. Genet. 256:397–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pfaller M. A., Castanheira M., Messer S. A., Moet G. J., Jones R. N. 2010. Variation in Candida spp. distribution and antifungal resistance rates among bloodstream infection isolates by patient age: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2008–2009). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 68:278–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pfaller M. A., et al. 2001. International surveillance of bloodstream infections due to Candida species: frequency of occurrence and in vitro susceptibilities to fluconazole, ravuconazole, and voriconazole of isolates collected from 1997 through 1999 in the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3254–3259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sanglard D., Ischer F., Bille J. 2001. Role of ATP-binding cassette transporter gene in high-frequency acquisition of resistance to azole antifungals in Candida glabrata. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1174–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sanglard D., Ischer F., Calabrese D., Majcherczyk P. A., Bille J. 1999. The ATP binding cassette transporter gene CgCDR1 from Candida glabrata is involved in the resistance of clinical isolates to azole antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2753–2765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sanguinetti M., et al. 2005. Mechanisms of azole resistance in clinical isolates of Candida glabrata collected during a hospital survey of antifungal resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:668–679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shahi P., Gulshan K., Naar A. M., Moye-Rowley W. S. 2010. Differential roles of transcriptional mediator subunits in regulation of multidrug resistance gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 21:2469–2482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sherman F., Fink G., Hicks J. 1979. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 32. Simonics T., et al. 2000. Isolation and molecular characterization of the carboxy-terminal pdr3 mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 38:248–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Srikantha T., et al. 1996. The Sea Pansy Renilla reniformis luciferase serves as a sensitive bioluminescent reporter for differential gene expression in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 178:121–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Srikantha T., Zhao R., Daniels K., Radke J., Soll D. R. 2005. Phenotypic switching in Candida glabrata accompanied by changes in expression of genes with deduced functions in copper detoxification and stress. Eukaryot. Cell 4:1434–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thakur J. K., et al. 2008. A nuclear receptor-like pathway regulating multidrug resistance in fungi. Nature 452:604–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Traven A., Wong J. M., Xu D., Sopta M., Ingles C. J. 2001. Interorganellar communication. Altered nuclear gene expression profiles in a yeast mitochondrial DNA mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 276:4020–4027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tsai H. F., Krol A. A., Sarti K. E., Bennett J. E. 2006. Candida glabrata PDR1, a transcriptional regulator of a pleiotropic drug resistance network, mediates azole resistance in clinical isolates and petite mutants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1384–1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vermitsky J. P., Edlind T. D. 2004. Azole resistance in Candida glabrata: coordinate upregulation of multidrug transporters and evidence for a Pdr1-like transcription factor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3773–3781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wolfger H., Mahé Y., Parle-McDermott A., Delahodde A., Kuchler K. 1997. The yeast ATP binding cassette (ABC) protein genes PDR10 and PDR15 are novel targets for the Pdr1 and Pdr3 transcriptional regulators. FEBS Lett. 418:269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wolfger H., Mamnun Y. M., Kuchler K. 2001. Fungal ABC proteins: pleiotropic drug resistance, stress response and cellular detoxification. Res. Microbiol. 152:375–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang X., Moye-Rowley W. S. 2001. Saccharomyces cerevisiae multidrug resistance gene expression inversely correlates with the status of the Fo component of the mitochondrial ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:47844–47852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]