Abstract

In this study, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was combined with the genetic detection of six genetic markers, ansB, dmsA, ggt, cj1585c, cjj81176-1367/71 (cj1365c), and the two-gene marker tlp7 (cj0951c plus cj0952c), to assess if their presence correlated with different C. jejuni clonal groups. Using a collection of 266 C. jejuni isolates from (in decreasing order of sample size) humans, chickens, cattle, and turkeys, it was further investigated whether the resulting genotypes correlated with the isolation source. We found combinations of the six marker genes to be mutually exclusive, and their patterns of presence or absence correlated to some degree with animal source. Together with MLST results, the obtained genotypes could be segregated into six groups. An association was identified for ansB, dmsA, and ggt with the MLST-clonal complexes (MLST-CC) 22, 42, 45, and 283, which formed the most prominent group, in which chickens were the most prevalent animal source. Two other groups, characterized by the presence of cj1585c, cjj81176-1367/71, and the two-gene marker tlp7, associated with either MLST-CC 21 or 61, were overrepresented in isolates of bovine origin. Mutually exclusive marker gene combinations were observed for ansB, dmsA, and ggt, typically found in CC 45 and the related CC 22, 42, and 283, whereas the other three marker genes were found mostly in CC 21, 48, and 206. The presence of the two-gene marker tlp7, which is typical for MLST 21 and 53 as well as for MLST-CC 61, strongly correlates with a bovine host; this is interpreted as an example of host adaptation. In cases of C. jejuni outbreaks, these genetic markers could be helpful for more effective source tracking.

Campylobacteriosis is the most common form of bacterial food-borne enteritis in both the developed and developing worlds (35). Campylobacter jejuni, the most prevalent microbial species leading to enteritis, has a wide range of hosts, varying from chickens, turkeys, cattle, and other mammals to humans (35).

Comparison of different C. jejuni genomes (10, 15, 26) led to the identification of numerous nonubiquitous genes. The presence or absence of four nonubiquitous genes was found to correlate with the source of the isolate (11). The authors of that study tested the presence of (i) dmsA, encoding a subunit of the putative tripartite anaerobic dimethyl sulfoxide oxidoreductase (DMSO/trimethylamine N-oxide reductase); (ii) cj1585c, encoding another oxidoreductase and replacing dmsA to -D in strain NCTC 11168; (iii) the serine protease gene cjj81176-1367/1371; and (iv) the γ-glutamyl-transpeptidase gene ggt (11). They identified that ggt and dmsA are present more frequently in isolates from humans and chickens, whereas cjj81176-1367/1371 and cj1581c are more common in bovine isolates.

Because the enzyme phosphofructokinase is absent, C. jejuni is unable to metabolize glucose. Instead, C. jejuni metabolizes free amino and keto acids originating mainly from the host or the normal flora of the hosts' intestine (22). Compounds such as succinate, d-lactate, malate, and formate serve as electron donors instead of glucose (14, 19, 26, 28, 32). In addition to the nonubiquitous ggt gene, the well-characterized strain 81-176 possesses a nonubiquitous accessory sec signal upstream of the asparaginase-encoding gene ansB, resulting in a periplasmic localization of the enzyme (16). This enables the strain to deaminate asparagine to aspartate, while no homolog of an asparagine transporter was detected in any of the known C. jejuni genome sequences (16). The periplasmic γ-glutamyl-transpeptidase seems to play a pivotal role in colonization of the chicken intestine. Knockout of ggt results in increased cell invasiveness (1). Because of this potentially important genetic determinant, we were interested in assessing the presence of ggt in combination with other genetic markers and investigating any possible association with host specificity.

Besides hydrogen and α-ketoglutarate, formic acid is a possible electron donor in the C. jejuni electron transport chain (33). Recently, we demonstrated that TLP7 (transducer-like protein 7), one of the group A receptors with structural similarity to methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) of Escherichia coli, mediates chemotaxis to formic acid and plays a role in host cell invasion and motility (31). In the strain huB2, like in NCTC 11168, the TLP7 receptor is a heterodimeric protein, and its gene is split into two parts: cj0951c, encoding the putative MCP domain-containing signal transduction protein, and cj0952c, encoding a HAMP-containing membrane protein and a CXXCH motif, indicating that it may be involved in the formate signaling pathway and/or formate respiration (GU799572). In contrast to the case for strains NCTC 11168 and huB2, both domains of TLP7 are encoded by a single gene in strain 81-176 (31). Because of these findings, we assumed that Cj0952c might even function on its own and that the introduction of a stop codon between cj0951c and cj0952c may be an expression of some sort of metabolic host adaptation. In order to discriminate between the single gene (tlp7) and the two-gene variant, we named the two-gene variant resulting in a heterodimeric receptor dtlp7 (cj0951c plus cj0952c).

In this study, the mutual relationships of ansB, ggt, dmsA, cj1585c, cjj81176-1367/1371 (cj1365c), and dtlp7 within isolates of human, chicken, bovine, and turkey origin and their association with multilocus sequence types-clonal complexes (MLST-CC) were investigated in order to reveal a possible relationship between clonal groups and metabolic adaptation indicative of host tropism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In the present study, 266 C. jejuni isolates from humans (128 isolates), chickens (66 isolates), cattle (45 isolates), and turkeys (27 isolates) were typed by MLST and screened for the six genetic markers mentioned above. For PCR detection of dtlp7 (cj0951c plus cj0952c), we used the primers tlp7-F01 (5′-AGG-TTT-CTG-CTG-CAA-TTT-TTG-TGG-TG-3′) and tlp7-R01 (5′-AGC-AAG-TTC-TCC-AAG-TTC-ATT-GCC-A-3′), followed by AseI restriction of the amplicon. AseI cuts the PCR fragment directly at the additional stop codon. Detection of ansB was performed using the primers ansB-F01 (5′-GGG-GAA-TGG-TAA-CTC-CAC-AA-3′) and ansA/B-R01 (5′-GCA-CTT-ATA-GCA-GTT-GAT-GGA-CG-3′), followed by NspI digestion of the PCR product. The NspI cutting site was localized within the sequence of the accessory sec signal. The primer pairs for the detection of dtlp7 and ansB were deduced from common regions of the published sequences of strains NCTC 11168 (26) and 81-176 (15). For PCR detection of dmsA, ggt, cjj81176-1367/1371, and cj1585c, we used primers that have already been described by Gonzalez et al. (11). MLST was conducted by using established primers (6). In order to construct a phylogenetic tree from the resulting sequences, using the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA), MEGA4 software was used (20). One thousand replicates of bootstrap analyses were carried out to fulfill confidence estimates for phylogenetic tree topology. For this study, we used the C. jejuni MLST website (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter/) developed by Keith Jolley and Man-Suen Chan and sited at the University of Oxford (18). MLST profiles and data for all isolates used in this work were submitted to the PubMLST database.

RESULTS

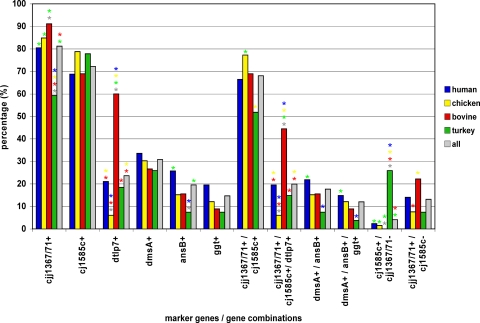

In the 266 isolates investigated, the marker gene cjj81176-1367/1371 was the most prevalent, detected in 216 isolates (81.2%). The cj1585c gene was found in 72.2% (192 isolates) of isolates, followed by dmsA (30.8%; 82 isolates), dtlp7 (23.7%; 63 isolates), ansB (19.5%; 52 isolates), and ggt (14.7%; 39 isolates). Figure 1 shows the distribution of these marker genes and of common combinations, split up according to the source of the isolates. This figure also demonstrates that cjj81176-1367/1371 and cj1585c were associated with each other in 68.0% (181/266 isolates) of the isolates. The marker gene dtlp7 seemed to be associated with bovine isolates: 60.0% (27/45 isolates) of these were dtlp7 positive. Only a minor proportion of the isolates were ggt positive. The frequency of ggt decreased from 19.5% (25/128 isolates) in human isolates to 12.1% (8/66 isolates) in chicken isolates, 8.9% (4/45 isolates) in bovine isolates, and 7.4% (2/27 isolates) in turkey isolates. This sequential finding (human > chicken > bovine > turkey), already described by Gonzalez and coworkers (7), could also be found for dmsA (33.6% [43/128 isolates] > 30.3% [20/66 isolates] > 26.7% [12/45 isolates] ≈ 25.9% [7/27 isolates]) and, to a lesser extent, ansB (25.8% [33/128 isolates] > 15.2% [10/66 isolates] ≈ 15.6% [7/45 isolates] > 7.4% [2/27 isolates]). Similar trends could be demonstrated for the combinations dmsA-ansB (21.9% [28/128 isolates] > 15.2% [10/66 isolates] ≈ 15.6% [7/45 isolates] > 7.4% [2/27 isolates]) and dmsA-ansB-ggt (14.8% [19/128 isolates] > 12.1% [8/66 isolates] > 8.9% [4/45 isolates] > 3.7% [1/27 isolates]). However, most of these frequency differences between the several host species were not significant, as indicated in Fig. 1. The presence of ggt coincided with that of ansB in 92% (36/39 isolates) of isolates and with that of dmsA in 90% (35/39 isolates) of isolates, whereas only 43% (35/82 isolates) of the dmsA-positive isolates and 69% (36/52 isolates) of the ansB-positive isolates were ggt positive. Furthermore, 90% (47/52 isolates) of ansB-positive isolates were dmsA positive, but only 57% (47/82 isolates) of dmsA-positive isolates showed the presence of ansB. There was no dtlp7-positive isolate showing the presence of ansB or ggt, and vice versa.

FIG. 1.

Frequency distribution of marker genes and marker gene combinations within C. jejuni isolates from different host species. cjj1367, cjj81176-1367/1371 gene (cj1365c), encoding a serine protease; cj1585c, gene encoding an oxidoreductase and replacing dmsA to -D in NCTC 11168; dtlp7, cj0951c and cj0952c genes, encoding the heterodimeric form of transducer-like protein 7; dmsA, gene encoding the dimethyl sulfoxide oxidoreductase subunit A; ansB, gene encoding an asparaginase with an accessory N-terminal sec-dependent secretion signal for periplasmic localization of the enzyme; ggt, gene encoding the γ-glutamyl-transpeptidase. Significant differences (P < 0.05) in values are marked by stars in the colors of the comparator values. A missing star indicates no significant (P > 0.05) difference.

Another group of isolates (4.1% [11/266 isolates]), mostly originating from turkeys (63.6% [7/11 isolates]), was cj1585c positive but cjj81176-1367/1371 negative. The reversed finding, of cj1585c-negative but cjj81176-1367/1371-positive isolates, was found more frequently in humans (51.4% [18/35 isolates]) and cattle (28.6% [10/35 isolates]).

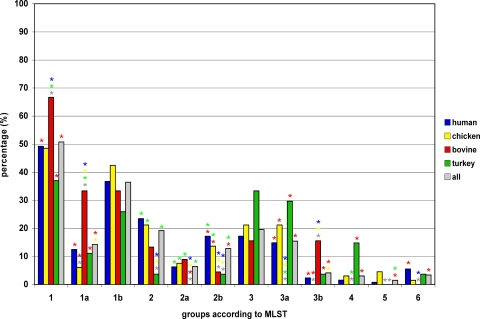

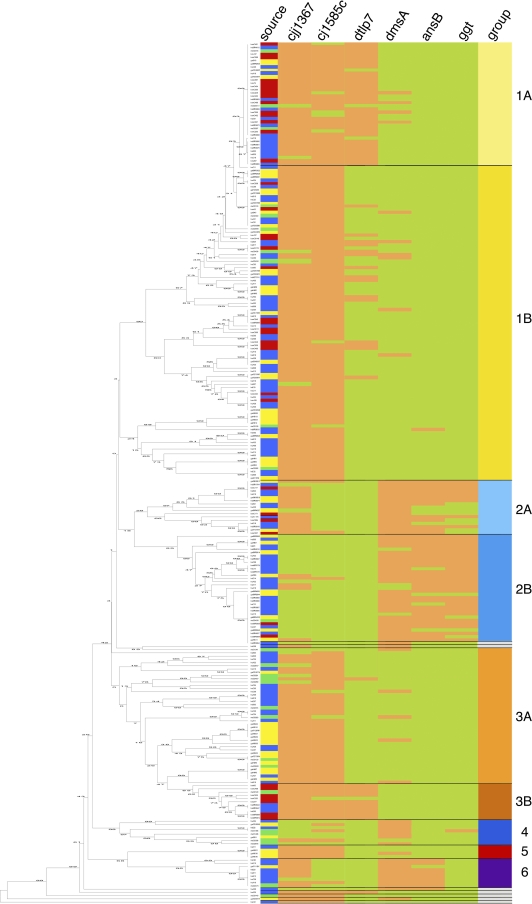

Additional MLST characterization of all 266 isolates led to the identification of six groups and nine subgroups, as can be seen in Table 1 as well as in Fig. 2 and 3 and in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of marker genes, MLST-CC, and isolate origins within the six determined groups and nine subgroups

| Group or subgroup | Most prevalent marker genesa |

CC | Origin(s)b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cjj1367 | cj1585c | dtlp7 | dmsA | ansB | ggt | |||

| 1a | X | X | X | 21 | b | |||

| 1b | X | X | 21, 48, 49, 206, 446 | h, c, b, t | ||||

| 2a | X | X | X | X | 22, 42 | h, c, b | ||

| 2b | X | X | X | 45, 283 | h, c | |||

| 3a | X | X | 52, 353, 354, 443, 658, 828 | h, c, t | ||||

| 3b | X | X | X | 61 | b | |||

| 4 | X | 1034, 1332 | t | |||||

| 5 | X | X | None | c | ||||

| 6 | X | X | X | 257 | h, t | |||

cjj1367, cjj81176-1367/1371 gene (cj1365c), encoding a serine protease; cj1585c, gene encoding an oxidoreductase and replacing dmsA to -D in NCTC 11168; dtlp7, cj0951c and cj0952c genes, encoding the heterodimeric form of transducer-like protein 7; dmsA, gene encoding the dimethyl sulfoxide oxidoreductase subunit A; ansB, gene encoding an asparaginase with an accessory N-terminal sec-dependent secretion signal for periplasmic localization of the enzyme; ggt, gene encoding the γ-glutamyl-transpeptidase.

h, human; c, chicken; b, bovine; t, turkey.

FIG. 2.

Frequency distribution of defined MLST-CC and marker gene-associated groups within C. jejuni isolates from different host species. Groups: 1, consisting of subgroups 1a and 1b; 2, consisting of subgroups 2a and 2b; 3, consisting of subgroups 3a and 3b; 4; 5; and 6. Significant differences (P < 0.05) in values are marked by stars in the colors of the comparator values. A missing star indicates no significant (P > 0.05) difference.

FIG. 3.

MLST-based UPGMA tree and arrangement of the six different marker genes within the six defined groups (nine subgroups). The MLST-based UPGMA tree for 266 C. jejuni isolates is depicted on the left. The numbers shown on the branches of the tree indicate the linkage distances. The right side shows a table of all isolates in the order of the UPGMA tree depicting the source of the isolate, the presence or absence of the six marker genes, and their association with one of the groups defined in Table 1. Sources: blue, human isolates; yellow, chicken isolates; red, bovine isolates; green, turkey isolates. The presence of a genetic marker is marked with light red, and its absence is marked with light green. The genetic markers, from left to right, are as follows: cjj1367, cjj81176-1367/1371 gene (cj1365c), encoding a serine protease; cj1585c, gene encoding an oxidoreductase and replacing dmsA to -D in NCTC 11168; dtlp7, cj0951c and cj0952c genes, encoding the heterodimeric form of transducer-like protein 7; dmsA, gene encoding the dimethyl sulfoxide oxidoreductase subunit A; ansB, gene encoding an asparaginase with an accessory N-terminal sec-dependent secretion signal for periplasmic localization of the enzyme; ggt, gene encoding the γ-glutamyl-transpeptidase. Groups: light yellow, 1a; intense yellow, 1b; cyan blue, 2a; bondi blue, 2b; carrot orange, 3a; orange-red, 3b; blue, 4; red, 5; purple, 6; white, singletons.

Major group 1 consisted of 50.8% (135/266 isolates) of all isolates and was characterized by the presence of cjj81176-1367/1371 and cj1585c. Isolates of this group originated from all four host species and belonged to the MLST-CC 21, 48, 49, 206, and 446. Within this group, subgroup 1a (14.3% of isolates [38/266 isolates]), of predominantly bovine isolates, was additionally positive for dtlp7.

The second group encompassed 19.2% (51/266 isolates) of the isolates and was predominantly positive for dmsA, ansB, and ggt. Within this group, subgroup 2a (6.4% of isolates [17/266 isolates]) was additionally positive for cjj81176-1367/1371. cjj81176-1367/1371-positive group 2a isolates belonged to the MLST-CC 22 and 42. cjj81176-1367/1371-negative group 2b isolates belonged to the MLST-CC 45 and 283. In group 2, isolates from chickens and humans were clearly overrepresented.

Similar to group 1, group 3 consisted of cjj81176-1367/1371- and cj1585c-positive isolates originating from all four host species and belonged to the MLST-CC 52, 353, 354, 443, 658, and 828. In this group, a dtlp7-positive subgroup (4.1% of isolates [11/266 isolates]) could be found, belonging exclusively to MLST-CC 61, with a large proportion of bovine isolates.

The majority of the group 4 isolates belonged to the MLST-CC 1034 or 1332 and tested positive for dmsA. Group 4 isolates were isolated mostly from turkeys.

Group 5 isolates, like those of groups 1b and 3a, tested positive for cjj81176-1367/1371 and cj1585c, and in most cases, they were isolated from chickens.

Finally, group 6 isolates of MLST-CC 257, originating from chickens and humans, were positive for dmsA, ansB, and cjj81176-1367/1371, comparable to group 2a isolates. In contrast to group 2a isolates, not one isolate in group 6 was positive for ggt. Thus, the higher prevalence of ansB than of ggt is due to group 6 isolates, and the higher prevalence of dmsA than of ggt and ansB is due to group 4 and 6 isolates.

DISCUSSION

The genotypic characterization performed here, based on the presence or absence of six metabolism-associated genetic markers in combination with MLST, divided the 266 isolates into six separate groups, of which three could be split into subgroups. These groups and subgroups showed moderate correlations with host origin. The observed host association was weaker than that observed for Campylobacter coli, which produces a more significant correlation between MLST-CC or amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) clusters and isolate source (17, 21, 24). The population of C. coli may display a higher degree of clonality than that of C. jejuni.

We identified three C. jejuni groups, groups 1, 3, and 5, in which the cjj81176-1367/1371 and cj1585c genes were associated. Within these groups, two subgroups of different clonality, 1a and 3b, were identified as having a two-gene organization for the TLP7 receptor, as described by Tareen and coworkers (31). Remarkably, this receptor variant was detected significantly (P < 0.001) more often in isolates from cattle. Epidemiological surveillance data collected in the year 2008 demonstrated that 6.7% of cattle herds, 4.7% of fresh bovine meat, and 1.3% of raw milk in Germany were contaminated with Campylobacter spp. and that more than 83% of bovine Campylobacter isolates belonged to the species C. jejuni (8). It has been assumed from different models that between 5% and 35% of all C. jejuni isolates from humans were transmitted via cattle or contaminated cattle products (5, 25, 27, 34). While 60% of the bovine isolates and about 20% of the human isolates harbored the heterodimeric receptor variant, it can be extrapolated that in accordance with the above-mentioned models, about one-third of all human C. jejuni isolates in our study originated in some way from cattle. This may suggest the use of dtlp7 as a marker for isolates of bovine origin. It is likely that cj0951c, encoding a putative MCP domain-containing signal transduction protein, does not interact exclusively with cj0952c; alternative and as yet unknown mechanisms may be responsible for adaptation to the bovine host. It has been demonstrated that MLST-CC 21 correlates with lipooligosaccharide (LOS) class C and that these isolates display more invasiveness in Caco-2 cells (13). Additionally, it is known that most hyperinvasive strains belong to MLST-CC 21 (9). Since subgroup 1a in particular is associated with MLST-CC 21, it can be deduced that this group represents C. jejuni strains with increased invasiveness.

Our data also revealed an association of ansB and dmsA in groups 2 and 6. In group 2, an additional association with ggt and also, for subgroup 2a, with cjj81176-1367/1371 could be identified. It seems that isolates with an extended amino acid metabolism are more prevalent in humans than previously recognized (11). The most likely transmission route of group 2 isolates, from chickens to humans, is consistent with the role of ggt in the persistent colonization of the avian intestine (1). Moreover, we identified a C. jejuni subpopulation of isolates belonging to MLST-CC 1034 or 1332 (group 4) that seems to circulate primarily within turkey populations and is encountered less frequently in humans. A similar finding was recently demonstrated for CC 403, which seems to represent a C. jejuni clone adapted to swine (23). Our results underscore the findings of Manning and coworkers showing that CC 21, 61, and 48 are overrepresented within bovine isolates and that CC 45, 257, and 283 originated from poultry, especially chicken (23). Due to their negativity for cjj81176-1367/71 (cj1365c), group 2b and 4 isolates may have originated from environmental sources, especially water (2; see below). Thus, poultry may function merely as an intermediate host for a minor proportion of this group, while a human-environment (water)-human transmission route is also possible.

There is also growing evidence for different C. jejuni subpopulations originating from different hosts and following different transmission routes. The most frequent MLST-CC in C. jejuni isolates from humans are MLST-CC 21 and 45 (7, 30), belonging to groups 1(a) and 2b, respectively. Habib and coworkers observed differences in the stress responses of the isolates belonging to these two MLST-CC (12): CC 21 strains were more tolerant to extreme temperatures, whereas CC 45 isolates showed increased survival in oxidative and freeze stress models. Thus, besides metabolic differences and preferences in host tropism, variation in stress responses may contribute to the establishment of certain C. jejuni lineages in defined environments. This is supported by the finding that campylobacteriosis cases caused by CC 21 or CC 45 isolates show different peaks in their temporal distribution (30). CC 45 isolates are more prevalent during the early summer months and seem to follow an environmental transmission route. In contrast, CC 21 cases are reported more or less consistently throughout the whole year, with a peak during late summer months (29) and with a clear association with infected cattle (3, 4).

Up to now, there are few genetic markers that can be used for effective source tracking. Champion and coworkers used genomotyping to identify a cluster of six genes, cj1321 to cj1326, within the O-linked flagellin glycosylation locus, which is absent in most nonlivestock isolates but present in almost every chicken/livestock-associated strain (2). These nonlivestock strains are potentially nonpathogenic and isolated mostly from asymptomatic carriers or from environmental sources. Additionally, Champion et al. demonstrated that the potential secreted serine protease gene cj1365c, which is the homologous gene to cjj81176-1367/71 in strain NCTC 11168, is absent in most isolates from environmental sources but present in clinical and livestock isolates. Thus, they hypothesized that it could be a marker for strains following an environmental transmission route, which could be the case for group 2b (CC 45) and group 4 (CC 1034 and 1332) isolates.

According to the data presented here, the mutually related marker genes ansB, dmsA, and ggt can be used to distinguish CC 45 and the related CC 283 from CC 22 and 42, which are additionally positive for cjj81176-1367/71 (cj1365c), and from CC 21 and its related CC 48 and 206, which are exclusively positive for cj1585c and cjj81176-1367/71 (cj1365c). The two-gene marker tlp7, typical for MLST 21 and 53 as well as MLST-CC 61, strongly indicates a host adaptation to cattle. This leads to the conclusion that the presence of dtlp7 in an outbreak strain is a significant indicator of a bovine source.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ortrud Zimmermann (UMG, Göttingen, Germany), Ingrid Hänel (FLI, Jena, Germany), and Kerstin Stingl (BfR, Berlin, Germany) for providing C. jejuni isolates.

This study was funded by the Forschungsförderungsprogramm of the Universitätsmedizin Göttingen, Germany.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 January 2011.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes, I. H., et al. 2007. Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase has a role in the persistent colonization of the avian gut by Campylobacter jejuni. Microb. Pathog. 43:198-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Champion, O. L., et al. 2005. Comparative phylogenomics of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals genetic markers predictive of infection source. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:16043-16048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark, C. G., et al. 2005. Use of the Oxford multilocus sequence typing protocol and sequencing of the flagellin short variable region to characterize isolates from a large outbreak of waterborne Campylobacter sp. strains in Walkerton, Ontario, Canada. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2080-2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark, C. G., et al. 2003. Characterization of waterborne outbreak-associated Campylobacter jejuni, Walkerton, Ontario. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:1232-1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Haan, C. P., R. I. Kivisto, M. Hakkinen, J. Corander, and M. L. Hanninen. 2010. Multilocus sequence types of Finnish bovine Campylobacter jejuni isolates and their attribution to human infections. BMC Microbiol. 10:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dingle, K. E., et al. 2001. Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dingle, K. E., et al. 2002. Molecular characterization of Campylobacter jejuni clones: a basis for epidemiologic investigation. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:949-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Food Safety Authority. 2010. The community summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in the European Union in 2008. EFSA J. 8:1496. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fearnley, C., et al. 2008. Identification of hyperinvasive Campylobacter jejuni strains isolated from poultry and human clinical sources. J. Med. Microbiol. 57:570-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouts, D. E., et al. 2005. Major structural differences and novel potential virulence mechanisms from the genomes of multiple Campylobacter species. PLoS Biol. 3:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez, M., M. Hakkinen, H. Rautelin, and M. L. Hanninen. 2009. Bovine Campylobacter jejuni strains differ from human and chicken strains in an analysis of certain molecular genetic markers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:1208-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Habib, I., M. Uyttendaele, and L. De Zutter. 2010. Survival of poultry-derived Campylobacter jejuni of multilocus sequence type clonal complexes 21 and 45 under freeze, chill, oxidative, acid and heat stresses. Food Microbiol. 27:829-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Habib, I., et al. 2009. Correlation between genotypic diversity, lipooligosaccharide gene locus class variation, and Caco-2 cell invasion potential of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from chicken meat and humans: contribution to virulotyping. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4277-4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffman, P. S., and T. G. Goodman. 1982. Respiratory physiology and energy conservation efficiency of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 150:319-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofreuter, D., et al. 2006. Unique features of a highly pathogenic Campylobacter jejuni strain. Infect. Immun. 74:4694-4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofreuter, D., V. Novik, and J. E. Galan. 2008. Metabolic diversity in Campylobacter jejuni enhances specific tissue colonization. Cell Host Microbe 4:425-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopkins, K. L., M. Desai, J. A. Frost, J. Stanley, and J. M. Logan. 2004. Fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism genotyping of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli strains and its relationship with host specificity, serotyping, and phage typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:229-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jolley, K. A., M. S. Chan, and M. C. Maiden. 2004. mlstdbNet-distributed multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) databases. BMC Bioinformatics 5:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly, D. J. 2001. The physiology and metabolism of Campylobacter jejuni and Helicobacter pylori. J. Appl. Microbiol. 175:102-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar, S., M. Nei, J. Dudley, and K. Tamura. 2008. MEGA: a biologist-centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief. Bioinform. 9:299-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lang, P., et al. 2010. Expanded multilocus sequence typing and comparative genomic hybridization of Campylobacter coli isolates from multiple hosts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:1913-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, M. D., and D. G. Newell. 2006. Campylobacter in poultry: filling an ecological niche. Avian Dis. 50:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manning, G., et al. 2003. Multilocus sequence typing for comparison of veterinary and human isolates of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6370-6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, W. G., et al. 2006. Identification of host-associated alleles by multilocus sequence typing of Campylobacter coli strains from food animals. Microbiology 152:245-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mullner, P., et al. 2009. Source attribution of food-borne zoonoses in New Zealand: a modified Hald model. Risk Anal. 29:970-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parkhill, J., et al. 2000. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 403:665-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schouls, L. M., et al. 2003. Comparative genotyping of Campylobacter jejuni by amplified fragment length polymorphism, multilocus sequence typing, and short repeat sequencing: strain diversity, host range, and recombination. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:15-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sellars, M. J., S. J. Hall, and D. J. Kelly. 2002. Growth of Campylobacter jejuni supported by respiration of fumarate, nitrate, nitrite, trimethylamine-N-oxide or dimethylsulfoxide requires oxygen. J. Bacteriol. 184:4187-4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sopwith, W., et al. 2008. Identification of potential environmentally adapted Campylobacter jejuni strain, United Kingdom. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1769-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sopwith, W., et al. 2006. Campylobacter jejuni multilocus sequence types in humans, northwest England, 2003-2004. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1500-1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tareen, A. M., J. I. Dasti, A. E. Zautner, U. Gross, and R. Lugert. 2010. Campylobacter jejuni proteins Cj0952c and Cj0951c affect the chemotactical behavior towards formic acid and are important for the invasion of host cells. Microbiology 156:3123-3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velayudhan, J., and D. J. Kelly. 2002. Analysis of gluconeogenic and anaplerotic enzymes in Campylobacter jejuni: an essential role for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. Microbiology 148:685-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weerakoon, D. R., N. J. Borden, C. M. Goodson, J. Grimes, and J. W. Olson. 2009. The role of respiratory donor enzymes in Campylobacter jejuni host colonization and physiology. Microb. Pathog. 47:8-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson, D. J., et al. 2008. Tracing the source of campylobacteriosis. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zautner, A. E., S. Herrmann, and U. Gross. 2010. Campylobacter jejuni—the search for virulence-associated factors. Arch. Lebensmittelhyg. 61:91-101. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.