Abstract

Increased numbers of adherent invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) have been found in Crohn's disease (CD) patients. In this report, we investigate the potential of the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) to reduce features associated with AIEC pathogenicity in an already established infection with AIEC reference strain LF82.

Imbalances in gastrointestinal microbial communities have been associated with many diseases, where the use of probiotics has been employed to artificially restore this unbalanced flora (8, 9, 20). Crohn's disease (CD), a clinical subtype of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), is a common chronic disorder that affects the gastrointestinal tract and is considered to develop due to an aberrant immune response to intestinal microbes in a genetically susceptible host (21). Over the last decade, high levels of adherent invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) have been reported in several studies of CD and highlighted the role of AIEC in the pathogenesis of this disease (2, 6, 16). Such an association is supported by the isolation of AIEC from 36% of ileal lesions in postsurgical resection of CD patients compared to just 6% in healthy controls (5). The AIEC reference strain LF82 has been isolated from the chronic ileal lesion of a patient with CD, and many studies have characterized the virulence factors that lead to its invasive abilities (1, 3, 6). On the other hand, probiotic bacteria have been used to manage IBD. Successful treatment has been reported with E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) in patients with IBD (13, 14, 17).

In this background, we investigated the question as to what impact EcN might have on an already established infection with the AIEC LF82 in the intestinal epithelial cell line Caco-2 with respect to invasion, cytokine profile, and paracellular permeability. The data were analyzed by Student's t test. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Unless stated otherwise, at least two biological experiments containing two replicate samples were performed for each experiment.

EcN inhibits invasion of LF82.

The Caco-2 cell line and bacterial strains were cultured as described previously (4, 11). Monolayers were seeded in 24-well tissue culture plates with 2 × 105 cells/well and incubated for 14 days. Each monolayer was infected in 1 ml of the cell culture medium without fetal calf serum (FCS) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 bacteria per epithelial cell.

After 3-h, 6-h, and 9-h incubation periods, bacterial invasion was measured using the gentamicin protection assay (7). After 6 h of infection, the number of invasive bacteria had increased (1.2 × 105 ± 9.5 × 104) compared with that observed at 3 h (2.3 × 104 ± 6.3 × 103). After this time point, the number of intracellular bacteria remained stable during the course of infection.

For the coinfection experiments, cells were infected with EcN (MOI of 10) after 3 h of monoinfection with strain LF82 and incubation was continued. After 6 h and 9 h of infection, the number of invasive bacteria was determined. As strain LF82 is naturally resistant to ampicillin, diluted samples of bacteria were plated on LB plates containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml) in order to quantify the number of invasive bacteria. After 6 h of coinfection, EcN showed an inhibitory effect on invasion by strain LF82 (P < 0.005), which was also demonstrated by Boudeau et al. (4).

EcN modifies the cytokine profile in Caco-2 cells after bacterial challenge with strain LF82.

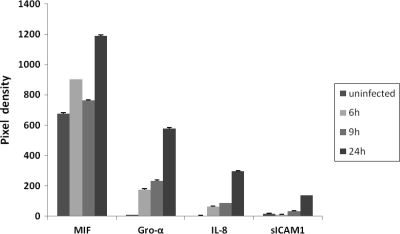

Proteome Profiler human cytokine array panel A (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used to determine the cytokine profile of Caco-2 cells after bacterial infection over a time course (6 h, 9 h, and 24 h postinfection) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Compared to uninfected cells, cells infected with strain LF82 secreted significantly increased levels of growth-regulated oncogene alpha (Gro-α), interleukin 8 (IL-8), and monocyte chemotactic peptide 1 (MCP-1) over the entire course of the experiment. Increased expression could also be detected for macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) at 6 h and 24 h after infection. Interestingly, uninfected Caco-2 cells also secrete large amounts of MIF (Fig. 1). Maaser et al. reported that MIF is ubiquitously produced at high levels by human intestinal epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo throughout the gastrointestinal tract (15). Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) were elevated in the supernatant at the 9-h time point. Furthermore, we could detect smaller amounts of secreted IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) in infected Caco-2 cells at 6 h postinfection compared to uninfected cells.

FIG. 1.

Caco-2 cells secrete large amounts of MIF. Uninfected Caco-2 cells and cells infected with strain LF82 for 6, 9, and 24 h are shown. Uninfected Caco-2 cells also secrete large amounts of MIF. For comparison, pixel densities are shown for Gro-α, IL-8, and sICAM1; only infected cells secrete these cytokines.

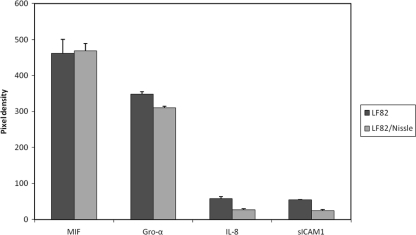

After 3 h of infection, EcN was added to strain LF82 for another 3 h. We used uninfected Caco-2 cells and cells infected with only strain LF82 as controls. Pixel densities and fold changes in cytokine secretion are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 1, respectively. Cells coinfected with EcN secreted smaller amounts of soluble ICAM1 (sICAM1), Gro-α, and IL-8 than cells infected only with strain LF82. Thus, infection with EcN decreased the levels of these cytokines secreted in coinfection experiments with strain LF82 compared to monoinfected cells. These results indicate that the anti-inflammatory effects of EcN can counteract the pathogenic LF82 strain by modification of cytokine expression and thereby minimize neutrophil migration and intestinal injury. It was previously described that probiotic bacteria suppress proinflammatory cytokine production from intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) (12, 18, 19).

FIG. 2.

E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) has an impact on the secretion of Gro-α, IL-8, and sICAM1 in coinfection experiments with strain LF82 (LF82/Nissle). For comparison, pixel densities are also shown for MIF, which was not influenced by EcN infection (P = 0.84).

TABLE 1.

Impact of the probiotic bacterium E. coli Nissle 1917 on the cytokine profile in Caco-2 cells after bacterial infection with E. coli LF82a

| Cytokine |

GenBank accession no. | Fold change in pixel density (exptl/control) in cells infected with the following E. coli strain(s)b: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Systematic namec | LF82 and EcN | LF82 | |

| Gro-α | CXCL1 | NM_001511 | 9,327 ± 109* | 10,476 ± 179** |

| IL-8 | CXCL8 | NM_000584 | 38.9 ± 4.6* | 84.7 ± 7.8* |

| sICAM1 | NM_000201 | 0.41 ± 0.03* | 0.92 ± 0.006*** | |

Impact of the probiotic bacterium E. coli Nissle 1917 on the cytokine profile in Caco-2 cells after bacterial infection with E. coli reference strain LF82 for 6 h.

Uninfected cells were used as the control. Changes in the amount of cytokines were calculated using the pixel densities for the single spots corresponding to the cytokines of the infected cells divided by the uninfected control cells. The results are represented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs) of duplicate samples from six pooled experiments. Only cytokines with significant differences are shown. To determine the influence of E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) on the different cytokines in double infection experiments, these results were compared with cells infected with only strain LF82 (monoinfected cells). A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant. Values that were significantly different from the control values are indicated as follows: *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.005.

CXCL1 and CXCL8, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligands 1 and 8, respectively.

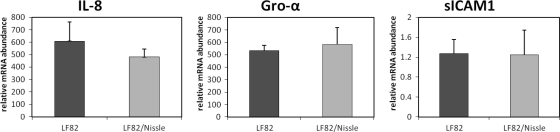

Real-time PCR-confirmed cytokine array data.

Total RNA was extracted from noninfected and infected Caco-2 cells using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and stored at −80°C. Reverse transcription of 1.4 μg of total RNA to cDNA was carried out using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis super mix kit (Invitrogen, Auckland, New Zealand) and oligo(dT)20 primers according to the standard protocol. Reactions were performed in 384-well plates as previously described (11), and the cDNA was amplified in an Applied Biosystems ABI PRISM 7900HT sequence detection system. The primers used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) are shown in Table 2. Relative mRNA expression was then calculated in comparison to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression using Pfaffl's formula: 2−ΔΔCT where CT is the threshold cycle. Six selected genes were analyzed for expression (IL-8, Gro-α, sICAM1, MCP-1, IL-1RA, and MIF) after 6 h of bacterial infection. IL-8 had the most pronounced upregulation in mRNA expression (869-fold increase), followed by Gro-α and MCP-1 (180-fold and 115-fold increase, respectively). Additionally, a modest upregulation was observed with sICAM1 (2.6-fold increase). Infection with strain LF82 also resulted in a downregulation for MIF (0.44-fold induction) and IL-1RA (0.6-fold induction) compared to uninfected cells. Next we measured the mRNA levels of IL-8, Gro-α, and sICAM1 in cells coinfected with EcN. We found significantly higher levels of IL-8 mRNA in 3 out 5 experiments for the monoinfected cells (cells infected with strain LF82) compared to the coinfected cells that were also infected with the probiotic bacterium (P < 0.01). No significant differences in gene expression levels could be found for Gro-α and sICAM1 (Fig. 3).

TABLE 2.

Primers used for real-time PCRa

| Gene | Directionb | Primer sequence | Primer length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-8 | F | 5′-CTGCGCCAACACAGAAATA-3′ | 238 |

| R | 5′-ATTGCATCTGGCAACCCTAC-3′ | ||

| Gro-α | F | 5′-CTCTTCCGCTCCTCTCCACAG-3′ | 218 |

| R | 5′-TGGATGTTCTTGGGGTGAAT-3′ | ||

| MCP-1 | F | 5′-GTCTCTGCCGCCCTTCTGTG-3′ | 94 |

| R | 5′-AGGTGACTGGGGCATTGATTG-3′ | ||

| sICAM1 | F | 5′-CCGTGGTCTGTTCCCTGTAC-3′ | 212 |

| R | 5′-TGTCTGCAGTGTCTCCTGGCT-3′ | ||

| IL-1RA | F | 5′-TGCAGAGCAGGAAACATGAC-3′ | 186 |

| R | 5′-TAGGGAACTTTGCACCCAAC-3′ | ||

| MIF | F | 5′-AGAACCGCTCCTACAGCAAG-3′ | 144 |

| R | 5′-ATTTCTCCCCACCAGAAGGT-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | F | 5′-CAAGGAGTAAGACCCCTGGA-3′ | 140 |

| R | 5′-GGGTCTACATGGCAACTGTG-3′ |

Primers were designed using the Oligo Perfect software from Invitrogen (Auckland, New Zealand).

F, forward; R, reverse.

FIG. 3.

Measurement of mRNA amounts after 6 h of infection with strain LF82 alone or in combination with EcN by qPCR analysis. All expression levels were normalized by comparison to the values for GAPDH controls and plotted as relative expression units, where the level of RNA expressed from uninfected cells was set at 1 (not shown). The results are presented as the means plus standard deviations (SDs) (error bars) of four replicate samples, and the results shown are from a representative experiment of five independent experiments.

Infection with strain LF82 results in an increase in paracellular permeability.

Caco-2 cells were grown to confluence on permeable polyethylene terephthalate (PET) membranes (Millipore Millicell hanging cell culture inserts with 0.4-μm pores; Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) (1 × 105 cells per filter). Experiments were performed with 14-day-old monolayers to ensure tight junction formation (10). The monolayers were infected as described above. After 5 h of infection, monolayers were placed in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) and allowed to equilibrate for 1 h. Apical medium was removed and replaced with HBSS containing 0.4 μCi of [2-3H]mannitol (10 to 20 Ci/mM) (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc., St. Louis, MO) per filter. The tracer concentrations in the apical and basolateral compartments were assayed at different time points (0 min, 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, and 60 min), and radioactivity was counted with a β-scintillation counter. LF82 infection led to an increase in the paracellular permeability for [3H]mannitol compared with uninfected control monolayers, and differences were statistically significant at the 60-min time point (P = 0.01). In order to determine whether the probiotic EcN can restore the barrier function disrupted by strain LF82, Caco-2 cells were infected with EcN after 3 h of infection with strain LF82 for 3 h. Treatment with EcN had no effect on the induced increase of mannitol flux in Caco-2 cells by strain LF82. In summary, our results suggest that EcN protects intestinal epithelial cells from the inflammation-associated response caused by strain LF82 by reducing pathogen invasion and modulating cytokine expression. This study is the first to our knowledge to show that EcN can reduce some of the negative effects associated with strain LF82 in an already established AIEC infection and emphasizes the potential of EcN in IBD treatment. In particular, the use of this probiotic could be of interest in CD patients harboring pathogenic AIEC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jin-Yong Jang for technical assistance and Amy Tatham and Ulrich Sonnenborn for critical reading of the manuscript. E. coli strain LF82 was a kind gift from A. Darfeuille-Michaud (Université Clermont I, Pathogénie Bactérienne Intestinale, Clermont-Ferrand, France). The probiotic strain E. coli Nissle 1917, also known as Mutaflor, was kindly provided by U. Sonnenborn (Ardeypharm, Herdecke, Germany).

This work was supported by Nutrigenomics New Zealand, a collaboration between AgResearch Ltd., Plant & Food Research, and The University of Auckland, with funding through the Foundation for Research Science and Technology. The funding sources for this study had no role in the study design or data collection, analysis, interpretation, and reporting.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnich, N., et al. 2007. CEACAM6 acts as a receptor for adherent-invasive E. coli, supporting ileal mucosa colonization in Crohn disease. J. Clin. Invest. 117:1566-1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgart, M., et al. 2007. Culture independent analysis of ileal mucosa reveals a selective increase in invasive Escherichia coli of novel phylogeny relative to depletion of Clostridiales in Crohn's disease involving the ileum. ISME J. 1:403-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boudeau, J., N. Barnich, and A. Darfeuille-Michaud. 2001. Type 1 pili-mediated adherence of Escherichia coli strain LF82 isolated from Crohn's disease is involved in bacterial invasion of intestinal epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1272-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudeau, J., A.-L. Glasser, S. Julien, J.-F. Colombel, and A. Darfeuille-Michaud. 2003. Inhibitory effect of probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 on adhesion to and invasion of intestinal epithelial cells by adherent-invasive E. coli strains isolated from patients with Crohn's disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 18:45-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darfeuille-Michaud, A., et al. 2004. High prevalence of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli associated with ileal mucosa in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 127:412-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darfeuille-Michaud, A., et al. 1998. Presence of adherent Escherichia coli strains in ileal mucosa of patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 115:1405-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falkow, S., P. Small, R. Isberg, S. Hayes, and D. Corwin. 1987. A molecular strategy for the study of bacterial invasion. Rev. Infect. Dis. 9(Suppl. 5):S450-S455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank, D., et al. 2007. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:13780-13785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimura, K. E., N. A. Slusher, M. D. Cabana, and S. V. Lynch. 2010. Role of the gut microbiota in defining human health. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 8:435-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hidalgo, I. J., T. J. Raub, and R. T. Borchardt. 1989. Characterization of the human colon carcinoma cell line (Caco-2) as a model system for intestinal epithelial permeability. Gastroenterology 96:736-749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huebner, C., I. Petermann, W. J. Lam, A. N. Shelling, and L. R. Ferguson. 2010. Characterization of single-nucleotide polymorphisms relevant to inflammatory bowel disease in commonly used gastrointestinal cell lines. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 16:282-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamada, N., et al. 2008. Nonpathogenic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 inhibits signal transduction in intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 76:214-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruis, W., et al. 2004. Maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis with the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is as effective as with standard mesalazine. Gut 53:1617-1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruis, W., et al. 1997. Double-blind comparison of an oral Escherichia coli preparation and mesalazine in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 11:853-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maaser, C., L. Eckmann, G. Paesold, H. S. Kim, and M. F. Kagnoff. 2002. Ubiquitous production of macrophage migration inhibitory factor by human gastric and intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology 122:667-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez-Medina, M., et al. 2009. Molecular diversity of Escherichia coli in the human gut: new ecological evidence supporting the role of adherent-invasive E. coli (AIEC) in Crohn's disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 15:872-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rembacken, B. J., A. M. Snelling, P. M. Hawkey, D. M. Chalmers, and A. T. Axon. 1999. Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli versus mesalazine for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. Lancet 354:635-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riedel, C. U., et al. 2006. Anti-inflammatory effects of bifidobacteria by inhibition of LPS-induced NF-κB activation. World J. Gastroenterol. 12:3729-3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sokol, H., et al. 2008. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:16731-16736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turnbaugh, P. J., et al. 2009. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 457:480-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xavier, R., and D. Podolsky. 2007. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 448:427-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]