Abstract

The inactivation of spores of four low-acid food spoilage organisms by high pressure thermal (HPT) and thermal-only processing was compared on the basis of equivalent thermal lethality calculated at a reference temperature of 121.1°C (Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa) and characterized as synergistic, not different or protective. In addition, the relative resistances of spores of the different spoilage microorganisms to HPT processing were compared. Processing was performed and inactivation was compared in both laboratory and pilot scale systems and in model (diluted) and actual food products. Where statistical comparisons could be made, at least 4 times and up to around 190 times more inactivation (log10 reduction/minute at FTz121.1°C) of spores of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus sporothermodurans, and Geobacillus stearothermophilus was achieved using HPT, indicating a strong synergistic effect of high pressure and heat. Bacillus coagulans spores were also synergistically inactivated in diluted and undiluted Bolognese sauce but were protected by pressure against thermal inactivation in undiluted cream sauce. Irrespective of the response characterization, B. coagulans and B. sporothermodurans were identified as the most HPT-resistant isolates in the pilot scale and laboratory scale studies, respectively, and G. stearothermophilus as the least in both studies and all products. This is the first study to comprehensively quantitatively characterize the responses of a range of spores of spoilage microorganisms as synergistic (or otherwise) using an integrated thermal-lethality approach (FTz). The use of the FTz approach is ultimately important for the translation of commercial minimum microbiologically safe and stable thermal processes to HPT processes.

High-pressure thermal (HPT) processing has been identified as a potential alternative to conventional thermal processing to deliver low-acid shelf-stable foods (LASSF) with improved sensory and nutritional qualities (5, 11, 15, 28). Previously, we have shown that, in laboratory scale experiments, the inactivation of spores of proteolytic Clostridium botulinum by HPT processing is similar to that achieved under thermal-only processing conditions compared on the basis of accumulated thermal lethality (FTz) (7). While we have noted some synergy between heat and high pressure for the inactivation of spores of proteolytic C. botulinum, this synergy appears to be dependent on both the strain and the product (7). Contrary to the case for proteolytic C. botulinum, there are a number of published studies suggesting that the most heat-resistant spoilage bacterium of concern for LASSF, Geobacillus stearothermophilus, is not nearly as resistant to thermal processing under high pressure as its heat resistance would predict (2, 14, 17, 21, 24). In comparison, strains of the aerobic mesophilic species Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, which produces spores with intermediate heat resistance, have been shown to produce highly HPT-resistant spores (1, 17, 18, 23) that under some conditions appear to be stabilized by high pressure against thermal inactivation (16). B. amyloliquefaciens is closely related to Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis, but to date, the spores of these related bacteria have been found to be relatively sensitive to HPT processing (17, 18, 26). A number of B. amyloliquefaciens strains have been proposed as relevant target spoilage organisms for HPT-processed LASSF (17, 18) and even as potential surrogates to assess the efficacy of HPT processes with respect to proteolytic C. botulinum (23).

In assessing the resistance of spores to inactivation by HPT processing compared with that achieved under thermal-only conditions, the primary approach of others (1, 14, 21, 23, 24) has been to compare inactivation as a function of the hold time, mostly assuming log-linear inactivation kinetics. For HPT inactivation, this approach ignores lethality accrued during the preheating, pressure come-up (CUT), and depressurization phases. Given the significant thermal component of HPT processes, it has been acknowledged that an approach similar to that of the integrated thermal-lethality concept used in traditional thermal processing might be more appropriate to express and predict inactivation (21, 29). The adoption of an integrated lethality approach would also manage the anticipated nonisothermal nature of commercial HPT processing. Some recent studies (25, 29) account for a nonisothermal hold time by calculating an equivalent time (teq) relative to the desired hold temperature using elements of the integrated thermal-lethality concept; however, these studies (25, 29) still disregard inactivation and time during the preheating, CUT, and depressurization phases in their overall assessments.

To date, the comparison of inactivation of spores by HPT and thermal-only processing on the basis of FTz at reference temperature (Tref), and over the entire process, has been reported only for C. botulinum and Clostridium sporogenes spores (7). There is a need to comprehensively and systematically assess the HPT resistances of other spore-forming species of interest for LASSF using this approach. The objective of this study was to characterize the effect of the combination of heat and high pressure on the inactivation of spores of G. stearothermophilus, B. amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus coagulans, and Bacillus sporothermodurans as synergistic, not different or protective, on the basis of equivalent integrated thermal lethality at 121.1°C (Fz121.1°C). Resistance was assessed in model (diluted) cream and Bolognese sauces and rice water agar processed in a laboratory scale 1.5-ml multivessel high-pressure system and in undiluted cream and Bolognese sauces processed in a pilot scale 3.6-liter high-pressure system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates and spore preparations.

Four representative organisms from our own culture collection (Food Research Ryde Bacteriology [FRR B]) that were identified as important with regard to the spoilage of LASSF (9, 19) were used in this study. B. amyloliquefaciens FRR B2782 (from black bean sauce) and B. sporothermodurans FRR B2706 (from canned coconut cream) were representative of obligate aerobic mesophiles, B. coagulans FRR B2723 (from satay sauce) was representative of a facultative thermophilic aerobe (also a facultative anaerobe), and G. stearothermophilus FRR B2792 (from milk powder) was representative of an obligate thermophilic aerobe.

Spores for each isolate were produced separately for studies conducted in the model and full products. For the model product studies, isolates were resuscitated on nutrient agar with 0.1% (wt/wt) starch (NAS); cells suspended in sterile deionized water (SDW) were dispensed onto the surface of the sporulation medium in 650-ml tissue culture flasks (Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany). The sporulation medium used (except for B. coagulans) was nutrient agar supplemented with mineral solution (NA + min), as described by Cazemier et al. (8), with modification (28 g/liter nutrient agar was used in place of nutrient broth and agar). B. coagulans was sporulated on Campden sporulation medium (6). B. amyloliquefaciens and B. sporothermodurans cultures were incubated for 5 to 7 days at 37°C, B. coagulans for 8 days at 45°C, and G. stearothermophilus for 7 days at 60°C, until sufficient spores were present (≥90% bright-phase spores by phase-contrast microscopy). Spores were harvested in SDW, washed/centrifuged (4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C) three times, and finally resuspended in SDW to a spore concentration of ∼109 CFU/ml.

For the full product studies, B. amyloliquefaciens was resuscitated in nutrient broth (NB) for 20 h at 37°C and the other isolates were resuscitated in a presporulation broth, TYG (12), as follows: B. coagulans for 20 h at 45°C, B. sporothermodurans for 48 h at 37°C, and G. stearothermophilus for 20 h at 60°C. The inoculum for each was prepared by transferring 10 μl of the resuscitated culture into 10 to 20 ml of fresh medium and incubating it as described for the resuscitated culture. One to 2 ml of the inoculum was dispensed over the surface of the sporulation medium; B. amyloliquefaciens and B. sporothermodurans were sporulated on Campden agar (37°C; 5 days), G. stearothermophilus on NA + min agar (60°C; 4 days), and B. coagulans on a modified version of NA + min agar, with 0.4% (wt/vol) yeast extract and 0.05% (wt/vol) glucose added (45°C; 5 days). Spores were collected in SDW, washed/centrifuged (5,500 × g for 45 min at 4°C) twice, and then purified using a sedimentation centrifugation method derived from that described by Nicholson and Setlow (20). The spores were resuspended in 5 to 10 ml 2% (wt/wt) Urografin (Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany) and centrifuged (5,500 × g for 1 h at 4°C) through 50% (wt/wt) Urografin. All Urografin concentrations given are based on the undiluted Urografin concentration of 76% (wt/vol). The pellets were washed/centrifuged (5,500 × g for 30 min at 4°C) twice in SDW and resuspended to yield a final spore concentration of 108 to 109 CFU/ml.

All spore suspensions were dispensed in 1-ml aliquots, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C until they were used. A viable-spore count (activation in SDW at 80°C for 10 min) was performed on a thawed vial of spores of each isolate. Activated spores were enumerated by the spread plate method (100 μl) on NAS. Prior to being counted, B. amyloliquefaciens plates were incubated for 20 to 24 h at 37°C, followed by 6 days at room temperature (RT); B. coagulans for 72 h at 37°C anaerobically (Anaerogen; Oxoid), followed by 4 days at 37°C aerobically; B. sporothermodurans for 48 h at 37°C, followed by 5 days at RT; and G. stearothermophilus for 4 days at 50°C. All samples generated in this study were recovered as described for spore crop enumeration, using buffered peptone water as the diluent.

Preparation of model and full products.

Bolognese sauce with minced beef, cream sauce, and long-grain rice were rendered commercially sterile by retorting them in pouches and stored at room temperature until required. Dilution of the products was required for laboratory scale inactivation studies to reduce their viscosity and/or particle size to facilitate loading and recovery from the small vessel volume of the high-pressure-processing (HPP) unit. The Bolognese sauce, cream sauce, and rice were diluted to 30, 50, and 40% (wt/wt), respectively, with SDW and blended as described previously (7). The water from the blended rice mixture was combined 1:1 with 3% (wt/vol) molten agar as previously described (7). The addition of agar was required to provide greater control of the prepressurization heating process. The final pHs of the model products were 4.74, 5.98, and 6.33 for the diluted Bolognese sauce, diluted cream sauce, and rice water agar, respectively.

The pHs of undiluted Bolognese and cream sauces, as used in the pilot scale inactivation studies, were 4.67 and 5.92, respectively. A rice product was not examined in the pilot scale inactivation studies.

Laboratory scale thermal-only inactivation of spores in model products.

The thermal-only resistances of all isolates were determined under isothermal conditions in each of the model products using laboratory scale equipment. Laboratory scale thermal-inactivation experiments were conducted in custom-made stainless steel screw-cap test tubes (13-mm inner diameter) fitted with silicon septa, according to the method previously described (7, 13). Test tubes filled (9.9 g) with uninoculated model product were fully immersed in a thermal-fluid (Thermal M solution; Julabo, Germany) bath at a set temperature. Once equilibrated to temperature, 100 μl of spore suspension was injected into each test tube and held for the desired time. Ten hold time points were examined in duplicate at three reference temperatures: B. amyloliquefaciens and B. sporothermodurans at 105, 110, and 115°C; B. coagulans at 100, 105, and 110°C; and G. stearothermophilus at 110, 115, and 118°C.

Using nonlinear least squares, a combined nonlinear model (log10 survivors versus time at the isothermal Tref) was fitted using R 2.10.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; as part of the RAndFriends software package) (3) to all inactivation data points, across all three process temperatures, to simultaneously estimate the decimal reduction time at a Tref of 121.1°C and 0.1 MPa (D121.1°C, 0.1 MPa), i.e., at atmospheric pressure, and the z value (the temperature difference required to produce a 10-fold change in the decimal reduction time), and standard deviations, in each model product. The time zero counts (based on the spore count after a standard activation process in SDW at 80°C for 10 min) were not used due to the potential for incomplete spore activation for some isolates using this treatment. Similarly, some early treatment points indicating an activation shoulder or lag were also excluded.

Laboratory scale HPT inactivation of spores in model products.

The pressure and heat resistances of all isolates were determined in each of the model products using laboratory scale equipment. Samples were pressure treated in a High Pressure Multi-Vessel Apparatus (model U111; Unipress Equipment, Warsaw, Poland) as previously described (7). HPT experiments were conducted, with the temperature profile measured by a triple-thermocouple assembly (K-type; Unipress) in an uninoculated sample while a single matched inoculated sample was processed at the same time and under the same conditions in a second stainless steel sample container.

The model product samples were inoculated to ∼105 (G. stearothermophilus only) to 106 CFU/g and processed at 600 MPa with pressure vessels preequilibrated to 102, 104, 106, or 108°C. The compression rate was ∼12 MPa/s, pressure hold times varied from 30 to 480 s, decompression took <10 s, and each HPT process was conducted twice; the vessel temperature, sample temperatures, and pressure were measured every 0.42 s (see Table S1 in the supplemental material for processing parameters and significant temperatures; typical pressure/thermal profiles for model product samples are provided in Bull et al. [7]). Immediately after the HPT process, samples were cooled in a 55°C water bath (to maintain the molten state of the rice water agar) before immediate enumeration of survivors using the whole sample. Due to variation in sample temperatures from run to run, we considered each “replicate” HPT treatment to be an independent process.

Given that the process was nonisothermal, the Fz121.1°C, 600 MPa value, the integrated thermal lethality, was calculated for each process by integrating equation 1 (4) using the trapezoidal integration method (10):

|

(1) |

Assumed z values, as determined under thermal-only conditions for the same batches of spores in the model products, were used in the calculation, with temperature data taken from the center of the sample, as measured by the middle of the three thermocouples. With the exception of G. stearothermophilus, for each microorganism in each product, a linear model (log10 survivors versus Fz121.1°C, 600 MPa) was fitted, using R (3), to all inactivation data points to estimate D121.1°C, 600 MPa, and the standard deviation. The time zero counts (based on the spore count after a standard activation process in SDW at 80°C for 10 min) were not used due to the potential for incomplete spore activation for some isolates using this treatment. For G. stearothermophilus, survivors from most HPT processes, in all three model products, were at and below the limit of detection. An alternative approach was adopted to determine a conservative estimate of D121.1°C, 600 MPa, fitting a linear model to survivor data for the shortest hold time process delivered in each product but including the estimated time zero count.

Pilot scale thermal-only inactivation of spores in full products.

The thermal-only resistances of all isolates were assessed under nonisothermal conditions in undiluted Bolognese and cream sauces using a pilot scale (internal chamber dimensions, 500 [height] by 440 [width] by 240 [depth] mm) programmable F Zero autoclave (Sabac Pty Ltd, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia). The unit is a modified version of a standard laboratory autoclave (model T62) enhanced to calculate FTz given a specified Tref and z value programmed into the unit's programmable logic controller (PLC). The ability to calculate FTz in real time, via an interface between the PLC and a linked computer running Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington), allows the PLC to be programmed to deliver a specified FTz, as controlled by temperature readings recorded by the unit's type T thermocouples.

Bulk quantities of sauce were inoculated to 105 to 107 CFU/g and homogenized. Individual samples (10 g) were poured into foil retort pouches (polyethylene teraphthalate, 12 μm; aluminum, 9 μm; nylon, 15 μm; reinforced cast polypropylene, 100 μm; CasPak Products Pty Ltd, Braeside, Victoria, Australia), which were then vacuum packed in a secondary pouch made from clear, retortable film (Vanr-70; Hosokawa Yoko Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). A preheating process was performed in a water bath, approximately 84 or 90°C (B. coagulans only) over 25 min, prior to processing in the F Zero autoclave. In conducting the preheating process for thermal-only-processed samples, care was taken to match the predicted thermal lethality delivered during preheating prior to HPT processing.

Five or 10 replicate samples were processed in each of 2 or 3 different processes programmed to deliver the desired FTz values, reaching a maximum temperature (Tmax) of either 110 or 115°C (B. coagulans only). Samples were laid flat and distributed over one or two shelves (five per shelf) of the four-shelf sample basket; the remaining two shelves were removed to improve temperature uniformity in the F Zero autoclave. The process was controlled by one thermocouple loosely inserted in an uninoculated dummy sample pouch, which was located on the higher of the two shelves; the dummy sample pouch was not vacuum sealed in retort film like the inoculated samples. After the processing, the samples were removed and cooled in room temperature water. Survivors were recovered from each sample using the methods described for enumerating the spore crops.

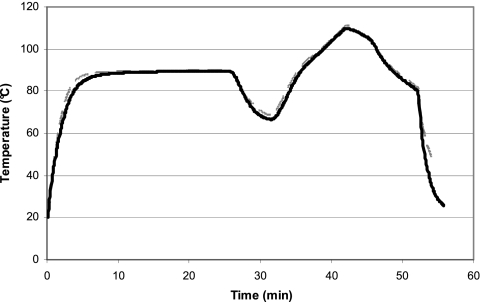

A representative sample thermal profile for each process was recorded by a Thermocron iButton High Capacity Temperature Logger Model DS1922T (Maxim Integrated Products, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) positioned inside an uninoculated sample pouch. Where samples were distributed over two shelves, an uninoculated sample packed with a Thermocron was located on both shelves. While the process was controlled using the unit thermocouple inside a dummy sample pouch, the thermal profile recorded by the Thermocron(s) was representative of the process performed on an actual sample, given that it was packed like the inoculated samples and because it also captured the preheating component of the process (Fig. 1 shows a typical thermal profile). Using the same approach described for the laboratory scale HPT experiments, the Fz121.1°C value was calculated for each process. Tref in this study was 121.1°C, and assumed z values, as determined for the spore batches of each isolate in the diluted version of each product, were used. Due to the potential for variation in temperature between shelves, an Fz121.1°C representative of samples on the top and the bottom shelves was calculated, and each was considered distinct from the other (see Table S2 in the supplemental material for processing parameters).

FIG. 1.

Typical temperature profile for undiluted product samples processed in the F Zero autoclave. The profiles are of two cream sauce temperature control samples and show the preheating process to 90°C over approximately 25 min, the drop in temperature experienced when samples were transferred from the preheating water bath to the autoclave, and the thermal process produced in the autoclave on the top (black solid line) and bottom (gray dashed line) shelves, achieving a maximum temperature of approximately 110°C.

For each microorganism in each product, the log10 reduction (i.e., log10 N/N0 CFU/g, where N is the spore count after treatment and N0 is the untreated spore count after a standard activation process in SDW at 80°C for 10 min) attained for each sample was calculated. The log10 reduction achieved per minute at 121.1°C (log10 reduction/Fz121.1°C) was estimated for each individual sample, and an average ± standard deviation was calculated for each data set.

Pilot scale HPT inactivation of spores in the full product.

Inoculated 10-g samples were prepared and packaged in the foil retort pouches as described for the pilot scale thermal-only-processed samples. Each HPT process was conducted with 12 sample pouches in the vessel; this included either 5 or 10 inoculated sample replicates, with the balance of the total 12 made up using uninoculated sample pouches. This ensured the sample load in the vessel was consistent in each HPT process. The 12 inoculated/uninoculated samples prepared for each HPT process were joined end to end into three groups of four; each of the three series of four sample pouches was further packed, individually, in a secondary, clear retort pouch filled with 200 ml of water (to provide additional thermal insulation from temperature loss during the high-pressure hold time). Each secondary packed sample pouch was secured, hanging vertically, on a metal frame designed to fit into the insulated sample carrier (polypropylene; 2.25-liter useable volume). Finally, a 10-ml polypropylene centrifuge tube filled with a “dummy” sauce product of equivalent viscosity to those being tested was secured at the center of the sample pouches to act as a temperature control; thermocouples were not inserted into actual sample pouches due to the potential for leakage. This packing configuration ensured that the exact vertical locations of individual inoculated sample pouches were known relative to one another.

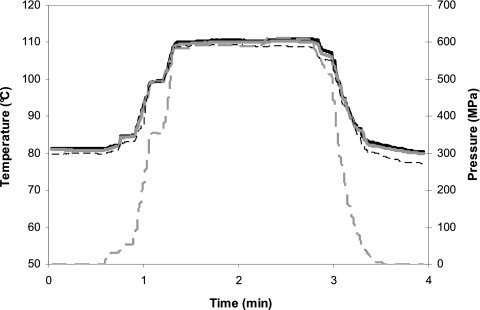

Five or 10 replicate samples were processed in each of 2 or 3 different HPT processes in a Stansted Iso-Lab FPG11501 HPP 3.6-liter unit (Stansted Fluid Power Ltd., Stansted, Essex, United Kingdom). Prior to HPT processing, the HPP unit vessel containing the sample carrier and filled with pressure-transmitting medium (deionized water-propylene-glycol mixture [35 to 40% glycol]) was preheated to approximately 84 or 90°C (B. coagulans only). Similarly, the sample rack was also preheated for 35 min in an external water bath at the same temperature. These preheating temperatures were selected to ensure the samples would reach a desired Tmax of approximately 110 or 115°C (B. coagulans only), respectively, as a result of compression heating (to 600 MPa), and also took into account slight temperature loss during transfer of samples to the HPP unit (∼3°C). At the completion of preheating, the HPP vessel was opened and the filled sample carrier was removed; the sample rack was immediately transferred into the sample carrier. The lid of the sample carrier was equipped with three T-type thermocouples positioned as follows: two of the three thermocouples were fed into the dummy temperature control tube, and the third thermocouple was immersed in the pressure-transmitting medium surrounding the samples. The carrier and samples were transferred to the HPP unit, and the samples were pressurized to 600 MPa (±5%) at a set compression rate of 1,200 MPa/min; with this selected compression rate, maximum pressure was typically achieved in a steplike fashion from 20 to 30 MPa (10 to 30 s) to approximately 300 MPa (15 s) and then to 600 ± 20 MPa (20 s). Hold times ranged from 5 to 130 s. At the conclusion of the hold time, the chamber was depressurized at a rate of 4,000 MPa/min; within 15 s of the initiation of decompression, the pressure typically fell to 500 MPa and then to 0.1 MPa within another 25 s (Fig. 2 shows a typical pressure/thermal profile; see Table S3 in the supplemental material for the processing parameters). After being processed, the samples were removed and cooled in room temperature water (∼23°C). Survivors were recovered from each sample using the methods described for enumerating the spore crops.

FIG. 2.

Typical temperature-pressure profile for undiluted product processed in a pilot scale 3.6-liter HP system. The profile is for a cream sauce sample in a pressure vessel preequilibrated to 83.5°C and processed at 600 MPa (±5%) with a 70-s pressure hold time. Shown are the temperatures inside a dummy sample-filled centrifuge tube recorded by thermocouples 1 (solid black line) and 2 (solid gray line), the temperature of the compression fluid surrounding the samples (dashed black line), and the pressure (dashed gray line). The sample was preheated to 83.5°C over 35 min prior to being transferred to the sample carrier and then to the pressure vessel (the preheating process was not recorded). During compression, the sample temperature increased to a maximum of approximately 110°C; during decompression, the sample temperature decreased to ∼80°C. Once removed, the samples were cooled to room temperature (cooling was not recorded).

Using the thermal profile recorded by the two unit thermocouples, the average Fz121.1°C, 600 MPa was calculated for each process using the method described previously. A Tref of 121.1°C and assumed z values, as determined for the spore batches of each isolate in the diluted versions of each product under thermal-only processing conditions, were used. The thermal profiles used for the calculations did not include the preheating process (because thermocouple recording did not commence until the HPT process was initiated); however, based on profiled preheating trials, preheating typically delivered maximum Fz121.1°C of 0.00 and 0.02 min, where the z values were 6.7 or 12, respectively, which translates to negligible log10 reduction values (data not shown).

For each microorganism in each product, the log10 reduction attained for each sample was calculated. The log10 reduction achieved per minute at Fz121.1°C, 600 MPa (log10 reduction/Fz121.1°C, 600 MPa) was estimated for each individual sample, and an average ± standard deviation was calculated for each data set.

Statistical analysis.

Spore inactivations by thermal-only and HPT processing in the diluted products/laboratory scale units were compared on the basis of average log10 reduction, ± standard deviation, achieved per minute at Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa (analogous to 1/D121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa). The reciprocals of DT values are approximately normally distributed, so their use for statistical analysis is preferred over the use of DT itself. A Welch t test was used to compare the average log10 reduction achieved per minute at Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa derived under thermal-only and HPT conditions for each isolate in each model product. P values of ≤0.05 indicated the difference was significant at the 95% confidence interval. P values of ≤0.01 indicated the difference was highly significant at the 99% confidence interval. Given that the estimation of the average log10 reduction achieved per minute at Fz121.1°C, 600 MPa for G. stearothermophilus spores in the dilute Bolognese and cream model products was based on one survivor data point only (due to survivor counts for longer hold time processes falling at or below the limit of detection), a statistical comparison of inactivations by thermal-only and HPT processing was not possible. While a statistical comparison of inactivation of G. stearothermophilus spores by both process types could be made in rice water agar, this was based on only two replicate HPT samples processed at one hold time; the resultant P value does not indicate a significant difference despite the large, obvious difference between the estimated average log10 reduction achieved per minute at Fz121.1°C, 600 MPa versus that at Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa.

Spore inactivations by thermal-only and HPT processing in the undiluted full product/pilot scale unit were compared based on the estimated log10 reduction ± standard deviation achieved per minute at Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa for each individual sample using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. P values of ≤0.01 indicated that they were highly significantly different at the 99% confidence interval. Analyses were conducted with the inclusion of censored data (i.e., data below the limit of detection of the recovery technique, approximately 1.7 log10 CFU/g). A value equivalent to the log10 of the square root of the limit of detection was used to calculate the log10 reduction for all censored observations. Where no inactivation or activation (an increase in the count compared to the untreated-spore count) was observed, these data were excluded from analyses. Statistical comparison for B. amyloliquefaciens in cream sauce was not possible due to a lack of inactivation under thermal-only conditions.

RESULTS

Thermal-only inactivation of spores in model and full products.

G. stearothermophilus was more resistant to thermal-only processing in all model products than the other isolates, particularly in the rice water agar, where an average log10 reduction of 0.14 ± 0.01 CFU/g was estimated (Table 1). The resistances of B. amyloliquefaciens and B. sporothermodurans were similar in all model products and were closer in resistance to G. stearothermophilus than to B. coagulans, which was considerably less heat resistant than the other isolates (Table 1). B. coagulans showed the least resistance in the cream model product, where an average log10 reduction of 34 ± 2.4 CFU/g was estimated per minute at Fz121.1°C (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Statistical comparison of resistances at equivalent Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa values of spoilage isolates in model products processed using laboratory scale thermal-only and HP systems

| Isolate | Model product | z value (°C)a | Thermal only |

HPT |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Avg log10reduction/min at Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa (CFU/g)b | Median (IQR)c | n | Avg log10reduction/min at Fz121.1°C, 600 MPa (CFU/g)d | Median (IQR) | ||||

| B. amyloliquefaciens FRR B2782 | 30% (wt/wt) Bolognese sauce | 11 ± 0.25 | 49 | 3.5 ± 0.31 | 3.5 (0.50) | 10 | 14 ± 2.7 | 14 (8.9) | 0.002e |

| 50% (wt/wt) cream sauce | 9.7 ± 0.39 | 58 | 2.2 ± 0.35 | 2.2 (0.50) | 18 | 17 ± 4.5 | 17 (17) | 0.002e | |

| Rice water agar | 7.8 ± 0.13 | 48 | 3.5 ± 0.19 | 3.5 (0.70) | 8 | 34 ± 3.0 | 35 (16) | <0.001e | |

| B. coagulans FRR B2723 | 30% (wt/wt) Bolognese sauce | 8.5 ± 0.23 | 48 | 17 ± 2.0 | 17 (7.1) | 8 | 43 ± 6.7 | 44 (9.5) | 0.004e |

| 50% (wt/wt) cream sauce | 6.7 ± 0.08 | 52 | 34 ± 2.4 | 34 (5.9) | 8 | 18 ± 1.9 | 17 (6.8) | 1.000 | |

| Rice water agar | 7.0 ± 0.15 | 60 | 22 ± 2.6 | 22 (6.6) | 8 | 15 ± 9.1 | 16 (21) | 0.741 | |

| B. sporothermodurans FRR B2706 | 30% (wt/wt) Bolognese sauce | 11 ± 0.32 | 43 | 1.6 ± 0.19 | 1.6 (0.30) | 7 | 10 ± 3.6 | 9.1 (7.9) | 0.033f |

| 50% (wt/wt) cream sauce | 7.0 ± 0.21 | 47 | 3.3 ± 0.29 | 3.3 (0.90) | 8 | 14 ± 3.2 | 16 (15) | 0.008e | |

| Rice water agar | 9.3 ± 0.18 | 55 | 1.7 ± 0.12 | 1.7 (0.40) | 8 | 8.3 ± 0.93 | 8.1 (3.5) | <0.001e | |

| G. stearothermophilus FRR B2792 | 30% (wt/wt) Bolognese sauce | 12 ± 0.26 | 48 | 0.74 ± 0.03 | 0.70 (0.10) | 2 | 120 | 120 (0.00) | NAg |

| 50% (wt/wt) cream sauce | 8.8 ± 0.29 | 42 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.40 (0.10) | 2 | 250 | 250 (0.00) | NA | |

| Rice water agar | 10 ± 0.36 | 60 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.10 (0.00) | 3 | 140 ± 36 | 140 (42) | 0.082 | |

z values (± standard deviation) were estimated using a nonlinear least-squares approach, fitting a nonlinear model (log10 survivors versus time) to all thermal-only data points generated for each isolate in each model product. Thermal-only z values were used to determine the equivalent thermal lethality, at a Tref of 121.1°C (Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa), delivered during all HPT processes.

Data values are the average log10 reductions (± standard deviation) estimated per minute at an equivalent Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa value of 1 min. D121.1°C, 0.1 MPa values were initially estimated (data not shown) using the nonlinear least-squares approach, fitting a nonlinear model (log10 survivors versus time) to all thermal-only data points generated for each isolate in each model product; the average log10 reduction achieved per minute at 121.1°C is analogous to 1/D121.1°C, 0.1 MPa.

IQR, interquartile range.

Data values are the average log10 reductions (± standard deviation) estimated per minute at an equivalent Fz121.1°C, 600 MPa value of 1 min under HPT (600 MPa) conditions. D121.1°C, 600 MPa values were initially estimated (data not shown) by fitting a linear model (log10 survivors versus Fz121.1°C, 600 MPa) to all HPT data points generated for each isolate in each model product; the average log10 reduction achieved per minute at 121.1°C and 600 MPa is analogous to 1/D121.1°C, 600 MPa.

P values of ≤0.01 indicate a statistically significant difference between the average log10 reduction per minute at Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa for the thermal-only and HPT data at the 99% confidence interval.

P values of ≤0.05 indicate a statistically significant difference between the average log10 reduction per minute at Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa for the thermal-only and HPT data at the 95% confidence interval.

NA, not applicable.

In the undiluted Bolognese and cream sauces, the thermal-only resistance of the four spoilage isolates followed trends similar to those observed in the model Bolognese and cream sauces, where G. stearothermophilus was most resistant and B. coagulans was least resistant (Table 2). The resistance of B. amyloliquefaciens in cream could not be estimated given that no inactivation was achieved during any process; the maximum Fz121.1°C delivered was 0.24 min.

TABLE 2.

Statistical comparison of resistances at equivalent Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa values of spoilage isolates in full products processed using pilot scale thermal-only and HP systems

| Isolate | Medium | Thermal only |

HPT |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (censored)a | Avg log10 reduction/min at Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa (CFU/g)b | Median (IQR)c | n (censored) | Avg log10 reduction/min at Fz121.1°C, 600 MPa (CFU/g) | Median (IQR) | |||

| B. amyloliquefaciens FRR B2782 | Bolognese sauce | 20 (6) | 6.5 ± 1.1 | 6.5 (1.2) | 20 (6) | 110 ± 35 | 100 (63) | <0.001d |

| Cream sauce | 25 (0) | No kille | No kill | 20 (9) | 35 ± 2.9 | 36 (2.9) | NAf | |

| B. coagulans FRR B2723 | Bolognese sauce | 25 (21) | 25 ± 7.2 | 23 (5.8) | 25 (22) | 32 ± 4.4 | 34 (6.2) | <0.001d |

| Cream sauce | 20 (5) | 70 ± 29 | 60 (33) | 20 (2) | 10 ± 4.1 | 9.4 (6.3) | <0.001d | |

| B. sporothermodurans FRR B2706 | Bolognese sauce | 5 (4) | 7.6 ± 0.46 | 7.8 (0.0) | 25 (4) | 70 ± 6.8 | 69 (5.2) | <0.001d |

| Cream sauce | 22 (0) | 17 ± 11 | 16 (22) | 25 (2) | 110 ± 33 | 100 (50) | <0.001d | |

| G. stearothermophilus FRR B2792 | Bolognese sauce | 10 (0) | 1.4 ± 0.10 | 1.4 (0.20) | 10 (8) | 70 ± 8.7 | 66 (14) | <0.001d |

| Cream sauce | 20 (0) | 0.51 ± 0.12 | 0.50 (0.20) | 25 (0) | 98 ± 30 | 88 (51) | <0.001d | |

Proportion of n that are censored data points; the log10 of the square root of the limit of detection was calculated to estimate survivors that were otherwise below the limit of detection.

Data values are the average log10 reductions (± standard deviation) estimated per minute at an equivalent Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa value of 1 min under thermal-only and HPT (600 MPa) conditions. Thermal-only z values (determined for initial spore batches in diluted model products) were used to determine the equivalent thermal lethality, at a Tref of 121.1°C (Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa), delivered during all nonisothermal thermal-only and HPT processes; the log10 reduction achieved per minute at 121.1°C for each individual sample is analogous to log10 reduction/Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa.

IQR, interquartile range.

P values of ≤0.01 indicate a statistically significant difference between the average log10 reduction per minute at Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa for the thermal-only and HPT data at the 99% confidence interval.

No inactivation or activation (an increase in count compared to the untreated-spore count) was observed for all samples, up to a maximum Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa of 0.24 min, and were excluded from analysis.

NA, not applicable.

Comparison of thermal-only and HPT inactivations of spores in model and full products.

G. stearothermophilus spores were by far the most sensitive to HPT treatment relative to thermal-only treatment, irrespective of the product or processing system (Tables 1 and 2). Inactivation of G. stearothermophilus spores by HPT processing was significantly greater (P < 0.01) than that achieved by thermally equivalent nonisothermal processes, with an average log10 reduction per minute at Fz121.1°C, in Bolognese and cream sauces, of 70 ± 8.7 and 98 ± 30 CFU/g compared to 1.4 ± 0.10 and 0.51 ± 0.12 CFU/g, respectively (Table 2); these values represent an average increase in (log10) inactivation under HPT conditions of around 50 and 190 times, respectively. Furthermore, based on comparison of inactivation delivered in the laboratory scale systems (without statistical comparison), less than 1 log10 reduction was achieved per minute at Fz121.1°C by heat alone compared to at least around 120 up to around 250 log10 CFU/g by HPT processing in 30% (wt/wt) Bolognese and 50% (wt/wt) cream sauces, respectively (Table 1). With the addition of pressure, an increase in inactivation from 0.44 ± 0.04 to around 250 log10 CFU/g per minute at Fz121.1°C was achieved in rice water agar (Table 1).

A variable comparative response, depending on the product and processing system, was demonstrated by B. coagulans spores. In diluted (model) and undiluted Bolognese sauce under HPT conditions, inactivation was statistically significantly (P < 0.05) higher than under thermal-only conditions, with an average log10 reduction per minute at Fz121.1°C of at least 32 ± 4.4 (Table 1) and 17 ± 2.0 (Table 2) CFU/g for each product/process type. In 30% (wt/wt) cream sauce and rice water agar, resistance was not statistically different (Table 1). However, in undiluted cream sauce processed in the pilot scale HPP system, inactivation of B. coagulans was highly statistically significantly (P < 0.01) lower than by thermal-only processing; average log10 reductions per minute at Fz121.1°C of 70 ± 29 and 11 ± 4.1 CFU/g were produced by heat alone and by HPT processing, respectively (Table 2).

Where a statistical comparison could be made, the HPT resistances of B. amyloliquefaciens and B. sporothermodurans spores were consistently significantly lower (P < 0.05, at least) than their thermal-only resistances. At a minimum, four times more inactivation was estimated in 30% (wt/wt) Bolognese and 50% (wt/wt) cream sauces (Table 1) and between 6 and 17 times more inactivation was delivered under HPT conditions in the undiluted sauces (Table 2). For example, in Bolognese sauce, average log10 reductions per minute at Fz121.1°C of 110 ± 35 and 70 ± 6.8 CFU/g were delivered by HPT processes compared to 6.6 ± 1.1 and 7.6 ± 0.46 by thermal-only processes for B. amyloliquefaciens and B. sporothermodurans, respectively (Table 2). Although no kill was delivered during the thermal-only processes with B. amyloliquefaciens spores in cream sauce (the maximum Fz121.1°C was 0.24 min), an average log10 reduction per minute at Fz121.1°C of 35 ± 2.9 CFU/g under HPT conditions was achieved (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

We compared inactivation by HPT and thermal-only processes using the integrated thermal lethality calculated at a Tref of 121.1°C (Fz121.1°C, 0.1 MPa or 600 MPa) to determine whether pressure acts synergistically with heat, or otherwise, to inactivate spores of different spoilage bacteria. Synergy was observed for all four spoilage bacteria in 30% (wt/wt) Bolognese sauce processed in a laboratory scale system and in undiluted Bolognese sauce processed in a pilot scale system. Synergy was also observed for three of four bacterial species (B. amyloliquefaciens, B. sporothermodurans, and G. stearothermophilus) in 50% (wt/wt) cream sauce and rice water agar processed in a laboratory scale system. The statistically significant synergistic effect of pressure on the inactivation of spores in undiluted cream sauce was confirmed for B. sporothermodurans and G. stearothermophilus processed in the pilot scale system; inactivation by HPT was presumed to be synergistic for B. amyloliquefaciens in cream sauce, also based on a comparison of average log10 reductions per minute at Fz121.1°C. Only for the spores of the least heat-resistant spore fomer, B. coagulans, was synergy not apparent in diluted and undiluted cream sauce or rice water agar. When processed in the laboratory scale systems in 50% (wt/wt) cream sauce or rice water agar, inactivation of spores of B. coagulans was not significantly different with or without pressure. When processed in undiluted cream sauce using the pilot scale HPP system, inactivation was significantly less in the combined high-pressure and heat system than that observed for the thermally equivalent thermal-only process, indicating apparent protection from thermal inactivation by high pressure.

The observation of highly significant synergy for G. stearothermophilus spores processed in food matrices by HPT compared to thermal-only treatment is consistent with those made in other studies. Patazca and others (21) showed that G. stearothermophilus ATCC 10149 spores processed in deionized water (pH 7.5) were considerably less resistant under HPT conditions than under thermal-only conditions, as indicated by a D121.1°C value of 5.5 min and an estimated D121.1°C, 600 MPa value of 0.1 min (based on the calculated D111°C, 600 MPa and a zT of 27.2°C) or average log10 reductions of 0.2 and 10.0 CFU/ml per minute at Fz121.1°C (i.e., 1/D121.1°C) at 0.1 and 600 MPa, respectively. Koutchma and others (14) estimated the same thermal-only and HPT D121.1°C values for strain G. stearothermophilus ATCC 7953 processed in egg patties at 121°C with and without 600 or 700 MPa of pressure. In our study, the estimated average log10 reductions under thermal-only conditions were comparable to those reported above, but under HPT conditions, resistance was substantially lower, indicating greater sensitivity of G. stearothermophilus FRR B2792 than of strains ATCC 10149 and 7953 to high pressure and heat. The degree of difference between thermal-only and HPT resistances was more pronounced here than in the above-mentioned studies and, incidentally, than those for the other strains examined here.

Similarly to G. stearothermophilus, B. sporothermodurans has been determined to be capable of producing highly heat-resistant spores that can survive ultra-high-temperature (UHT) processes ranging from 135 to 142°C (22). In this study, as with G. stearothermophilus, inactivation by HPT was consistently synergistic for the spores of B. sporothermodurans. To our knowledge, this is the first reported study characterizing the relative sensitivity of spores of B. sporothermodurans to HPT processing compared with thermal-only processing.

In contrast, the least heat-resistant isolate, B. coagulans, produced spores whose inactivation by heat was not always improved by the addition of pressure. Indeed, spores of B. coagulans were shown to be significantly protected from inactivation in cream sauce during HPT processing. The HPT-resistant nature of this strain of B. coagulans, FRR B2723, was established by Scurrah and others (26), who demonstrated an average 0.5 log10 CFU/ml reduction in skim milk processed at 600 MPa for 1 min at an initial temperature of 72°C (estimated Tmax, ∼95°C). This degree of resistance was dissimilar to those of the other two strains of B. coagulans examined (3.7 and 5.4 log10 reduction) by Scurrah and others (26), indicating that FRR B2723 may be peculiarly HPT resistant. In this study, when processed in either Bolognese or cream sauce in the pilot scale HPP system, B. coagulans produced by far the most HPT-resistant spores of all species examined.

The observation of variability in HPT resistance within a species noted for B. coagulans (26) has also previously been observed among strains of proteolytic C. botulinum (17) and B. subtilis (18); however, for the several B. amyloliquefaciens strains examined to date by others (1, 17, 18, 23), all have been shown to produce similarly highly HPT-resistant spores in comparison to those of other species examined. In particular, strain TMW 2.479 (Fad 82) has received attention as a potential HPT nonpathogenic surrogate for proteolytic C. botulinum since its resistance to HPT processing was first assessed by Margosch and others (17). The B. amyloliquefaciens strain examined here, FRR B2782, produced spores that were consistently and significantly more sensitive to inactivation by HPT than by thermally equivalent thermal-only processes. B. amyloliquefaciens FRR B2782 showed intermediate HPT resistance overall compared to the other three species examined. The resistance of our strain is most similar to that determined for strain TMW 2.479 in studies by Ahn et al. (1) and Rajan et al. (23) in deionized water and egg patties (pH 7.25) processed at 121°C and ±700 MPa and 121°C and ±600 MPa, respectively. The average log10 reductions estimated per minute at Fz121°C (analogous to 1/D121°C) under thermal-only and HPT conditions were 5.0 and 10, and 4.0 and 9.1 in each study, respectively, compared to 3.5 and 34 log10 CFU/g in rice water agar (pH 6.33) in this study. An increase in inactivation with the addition of pressure is, therefore, shared by all the studies, though the degree of increase was greatest in our study reported here. Such variation could be attributed to the physiological differences that arise between strains and/or as a function, for example, of sporulation conditions and processing menstruum compositions (5).

The experimental design and analysis approach can potentially affect conclusions made regarding spore responses to HPT processing. The use of the FTz approach is ultimately important for the translation of commercial minimum microbiologically safe and stable thermal processes to HPT processes. Bull and others (7) emphasized the benefit of measuring HPT inactivation against FTz, thereby accounting for thermal lethality delivered over the entire process rather than assessing resistance as a function of the pressure hold time. As discussed above, the latter approach has its limitations because significant contribution to lethality can occur during the CUT and depressurization phases and because, in reality, HPT equipment design limitations mean that maintaining isothermal conditions during the hold phase is difficult, particularly for longer hold times. The suggestion in some studies (24, 27) that tailing in spore HPT inactivation curves may be indicative of pressure-resistant subpopulations or pressure adaptation could rather be interpreted in terms of a reduction in temperature, and subsequent thermal lethality, during the hold phase in the (typically) nonadiabatic HPT system; however, despite the advantages of the FTz approach, it is important to note that the approach ideally requires knowledge of zT under pressure, and the acknowledged technical difficulties in gaining this knowledge may limit the approach. In this study, we elected to assume that thermal-only zT values do not change under HPT conditions. Generally, zT values under HPT conditions have been found, given hold time kinetics only, to be greater than those determined under thermal-only conditions (14, 21, 23, 25, 29), indicating that spores are less sensitive to temperature changes during HPT than during thermal-only processing. Therefore, by utilizing thermal-only zT values to derive FTz values under HPT conditions, our results may underestimate resistance. Such an underestimation may subsequently affect observations of synergy or protection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge C. McAuley, K. King, H. Craven, S. Ng, G. Knight, and K. Sultana for their excellent technical assistance and K. Knoerzer and P. Sanguansri for their advice on operation of the high-pressure unit.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 January 2011.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, J., V. M. Balasubramaniam, and A. E. Yousef. 2007. Inactivation kinetics of selected aerobic and anaerobic bacterial spores by pressure-assisted thermal processing. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 113:321-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ananta, E., V. Heinz, O. Schlueter, and D. Knorr. 2001. Kinetic studies on high-pressure inactivation of Bacillus stearothermophilus spores suspended in food matrices. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2:261-272. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baier, T., and E. Neuwirth. 2007. Excel :: COM :: R. Comput. Stat. 22:91-108. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakalis, S., P. W. Cox, and P. J. Fryer. 2001. Modeling particular thermal technologies, p. 113-137. In P. Richardson (ed.), Thermal technologies in food processing. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, England.

- 5.Black, E. P., et al. 2007. Response of spores to high-pressure processing. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 6:103-119. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, K. L. 1984. Spore studies in relation to heat processed food. Campden and Chorleywood Food Research Association, Chipping Campden, United Kingdom.

- 7.Bull, M. K., S. A. Olivier, R. J. van Diepenbeek, F. Kormelink, and B. Chapman. 2009. Synergistic inactivation of spores of proteolytic Clostridium botulinum strains by high pressure and heat is strain and product dependent. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:434-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cazemier, A. E., S. F. M. Wagenaars, and P. F. ter Steeg. 2001. Effect of sporulation and recovery medium on the heat resistance and amount of injury of spores from spoilage bacilli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 90:761-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evancho, G. M., S. Tortorelli, and V. N. Scott. 2009. Microbiological spoilage of canned foods, p. 185-221. In W. H. Sperber (ed.). Compendium of the microbiological spoilage of food and beverages. Springer, New York, NY.

- 10.Food Science Australia and D. Warne. 2005. Australian quarantine inspection service approved persons course for thermal processing of low-acid foods. Food Science Australia, Werribee, Australia.

- 11.Juliano, P., et al. 2006. Texture and water retention improvement in high-pressure thermally treated scrambled egg patties. J. Food Sci. 71:E52-E61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim, J., and H. B. Naylor. 1966. Spore production by Bacillus stearothermophilus. Appl. Microbiol. 14:690-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kooiman, W. J., and J. M. Geers. 1975. Simple and accurate technique for the determination of heat resistance of bacterial spores. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 38:185-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koutchma, T., B. Guo, E. Patazca, and B. Parisi. 2005. High pressure-high temperature sterilization: from kinetic analysis to process verification. J. Food Proc. Eng. 28:610-629. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leadley, C. 2005. High pressure sterilization; a review. Campden and Chorleywood Food Research Association, Chipping Campden, United Kingdom.

- 16.Margosch, D., et al. 2006. High-pressure-mediated survival of Clostridium botulinum and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens endospores at high temperature. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3476-3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Margosch, D., M. A. Ehrmann, M. G. Gänzle, and R. F. Vogel. 2004. Comparison of pressure and heat resistance of Clostridium botulinum and other endospores in mashed carrots. J. Food Prot. 67:2530-2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Margosch, D., M. G. Gänzle, M. A. Ehrmann, and R. F. Vogel. 2004. Pressure inactivation of Bacillus endospores. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:7321-7328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.May, N., and J. Archer. 1998. Heat processing of low acid foods: an approach for selection of F0 requirements. Campden and Chorleywood Food Research Association, Chipping Campden, United Kingdom.

- 20.Nicholson, W. L., and P. Setlow. 1990. Sporulation, germination and outgrowth, p. 391-450. In C. R. Harwood and S. M. Cutting (ed.) Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 21.Patazca, E., T. Koutchma, and H. S. Ramaswamy. 2006. Inactivation kinetics of Geobacillus stearothermophilus spores in water using high-pressure processing at elevated temperatures. J. Food Sci. 71:110-116. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pettersson, B., F. Lembke, P. Hammer, E. Stackebrandt, and F. G. Priest. 1996. Bacillus sporothermodurans, a new species producing highly heat-resistant endospores. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:759-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajan, S., J. Ahn, V. M. Balasubramaniam, and A. E. Yousef. 2006. Combined pressure-thermal inactivation kinetics of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens spores in egg patty mince. J. Food Prot. 69:853-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajan, S., S. Pandrangi, V. M. Balasubramaniam, and A. E. Yousef. 2006. Inactivation of Bacillus stearothermophilus spores in egg patties by pressure-assisted thermal processing. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 39:844-851. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramaswamy, H. S., Y. Shao, and S. Zhu. 2010. High-pressure destruction kinetics of Clostridium sporogenes ATCC 11437 spores in milk at elevated quasi-isothermal conditions. J. Food Eng. 96:249-257. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scurrah, K. J., R. E. Robertson, H. M. Craven, L. E. Pearce, and E. A. Szabo. 2006. Inactivation of Bacillus spores in reconstituted skim milk by combined high pressure and heat treatment. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101:172-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, B., et al. 2009. Inactivation kinetics and reduction of Bacillus coagulans spore by the combination of high pressure and moderate heat. J. Food Proc. Eng. 32:692-708. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson, D. R., L. Dabrowski, S. Stringer, R. Moezelaar, and T. Broklehurst. 2008. High pressure in combination with elevated temperature as a method for the sterilization of food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 19:289-299. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu, S., F. M. Naim, H. Marcotte, H. Ramaswamy, and Y. Shao. 2008. High-pressure destruction kinetics of Clostridium sporogenes spores in ground beef at elevated temperatures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 126:86-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.