Abstract

The modification of enzyme cofactor concentrations can be used as a method for both studying and engineering metabolism. We varied Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial NAD levels by altering expression of its specific mitochondrial carriers. Changes in mitochondrial NAD levels affected the overall cellular concentration of this coenzyme and the cellular metabolism. In batch culture, a strain with a severe NAD depletion in mitochondria succeeded in growing, albeit at a low rate, on fully respiratory media. Although the strain increased the efficiency of its oxidative phosphorylation, the ATP concentration was low. Under the same growth conditions, a strain with a mitochondrial NAD concentration higher than that of the wild type similarly displayed a low cellular ATP level, but its growth rate was not affected. In chemostat cultures, when cellular metabolism was fully respiratory, both mutants showed low biomass yields, indicative of impaired energetic efficiency. The two mutants increased their glycolytic fluxes, and as a consequence, the Crabtree effect was triggered at lower dilution rates. Strikingly, the mutants switched from a fully respiratory metabolism to a respirofermentative one at the same specific glucose flux as that of the wild type. This result seems to indicate that the specific glucose uptake rate and/or glycolytic flux should be considered one of the most important independent variables for establishing the long-term Crabtree effect. In cells growing under oxidative conditions, bioenergetic efficiency was affected by both low and high mitochondrial NAD availability, which suggests the existence of a critical mitochondrial NAD concentration in order to achieve optimal mitochondrial functionality.

Many metabolic engineering strategies rely on the manipulation of enzyme levels to achieve the amplification, interruption, or addition of a metabolic pathway. Modification of enzyme cofactor concentration is another, relatively unexplored tool for both studying and engineering the metabolism of a cell. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, second only to ATP, pyridine coenzymes are involved in hundreds of reactions (10). Manipulation of their cellular contents as well as their intracellular compartmentalization would be expected to deeply affect the overall cellular metabolism by determining modifications in the redox potential of subcellular compartments. Mitochondrial NAD-dependent dehydrogenase reactions can affect the rate of respiration and the overflow metabolism, thus influencing the production of ethanol, glycerol, and biomass (18, 32). Mitochondrial NAD is also crucial for anabolism; for example, the synthesis of many intermediates of the amino acid pathway(s) generated by the Krebs cycle is strongly dependent on the mitochondrial NAD+/NADH ratio (21, 34). The regulation of catabolism and anabolism by mitochondrial NAD has been extensively studied in plants, where the physiological modulation of mitochondrial NAD+ content has long been postulated and the proteins responsible for it have been recently identified (23). Moreover, many studies have shown that in plants, mitochondrial NAD+ content and/or the NAD+/NADH ratio affects the activities of many important dehydrogenases (such as glycine, malate, and isocitrate dehydrogenase) (6, 20, 26). Accordingly, computer modeling of the mitochondrial metabolism has predicted NAD to be the most important regulator of the mammalian tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (34). Besides being a molecule central to metabolism, NAD is involved in several other cellular processes, such as gene expression regulation via NAD-dependent histone deacetylation, ADP-ribosylation, poly-ADP-ribosylation, synthesis of Ca2+-mobilizing molecules such as nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP), cADP-ribose (36), and extension of life span by calorie restriction (22), among others. Recently, it has been shown that in mammalian cells, an increase in the amount of mitochondrial NAD can prevent apoptosis induced by genotoxic agents (35).

In eukaryotic cells, a significant proportion of cellular NAD is contained in the mitochondria (8). Despite the importance of NAD in yeast metabolism and cell biology, very little information about the role of the compartmentalization of this coenzyme in mitochondria is available. Only recently, overflow metabolism in S. cerevisiae at the pyruvate branch point has been shown to be reduced in strains having a lower mitochondrial NADH content, determined by expression of a heterologous alternative oxidase (18, 32).

In S. cerevisiae, the net biosynthesis of pyridine nucleotides takes place in the cytoplasm. Two mitochondrial carriers encoded by the NDT1 and NDT2 genes, transferring NAD+ from the cytoplasm to the mitochondrial matrix, have been identified recently (27). In the present paper, in order to advance understanding of the compartment-dependent regulation of NAD homeostasis, we investigated the physiological effects determined by an NDT1 NDT2 double deletion and NDT1 overexpression on cells growing in batch and glucose-limited chemostat cultures. Our studies indicate that both the increase and decrease in NAD+ transport into mitochondria cause a change in cellular NAD and a decrease in ATP content when cells are grown under respiratory conditions. Furthermore, our data suggest that the specific glucose uptake rate and/or the glycolytic flux should be considered one of the most important variables for establishing the long-term Crabtree effect in yeast.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains.

Strains generated in this work derive from strain CEN.PK 113-7D (MATa MAL2-8c SUC2) (28). In the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain, NDT1 and NDT2 genes were replaced by homologous recombination with the KanMX3 and HphMX4 cassettes, conferring resistance to G418 and hygromycin B, respectively (13). A strain overexpressing NDT1 (ndt1-over strain) was obtained by the one-step substitution of the chromosomal NDT1 promoter for the TDH3 promoter (PTDH3). Its sequence has been demonstrated to drive the constitutive and strong overexpression of downstream genes (16). To this end, we constructed a promoter-substitution cassette, with NatMX4 as a selectable marker for nourseothricin resistance, by cloning PTDH3 amplified from S. cerevisiae genomic DNA into the NdeI and HindIII sites of the pAG25 vector (13). The promoter-substitution cassette (PTDH3-NatMX4) was amplified from the pAG25-PTDH3 vector with primers containing at their extremities 75 bp homologous to the nucleotides flanking the 150-bp chromosomal region upstream of the NDT1 start codon. Following appropriate selection, the accuracy of all gene replacements and correct integrations were verified by PCR. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Culture media and growing conditions.

Both for batch and for chemostat cultures, yeast cells were grown in a defined medium made up of salts and vitamins as described previously (33). Since no metabolizable carbon source was present, the medium was supplemented with glucose, galactose, raffinose, or ethanol. For batch experiments, the carbon source was added to a concentration of 20 g liter−1 (or 15.6 g liter−1, in the case of ethanol). Chemostat cultures were run as described previously (24), with a glucose concentration of 7.5 g liter−1.

YPD medium (yeast extract at 10 g liter−1, peptone at 20 g liter−1, glucose at 20 g liter−1) was used for inoculum preparation and for preliminary batch characterization of the strains.

Growth rates under the various conditions were determined with the following procedure. Starting from a frozen (−80°C) working cell bank, cells were recovered overnight in YPD and precultured in defined medium supplemented with the required carbon source. Once the culture reached an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of 0.1 to 0.5, cells were inoculated in a new flask, and the specific growth rate in the OD660 range of 0.1 to 1.0 was determined. Each determination was repeated in at least three independent experiments.

Cell dry weight was measured by filtering a known volume of the culture through a preweighed 0.45-μm nitrocellulose filter (Millipore GSW) and drying the filter in a microwave oven for 6 min at 200W.

Isolation of mitochondria.

The isolation of mitochondria was carried out as previously described (27) and performed essentially as follows. Spheroplasts were prepared by using Zymolyase 20T and then disrupted by 13 strokes in a cooled Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer with hypotonic medium. Cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were separated by differential centrifugation. Cellular lysates were centrifuged at 2,800 × g for 10 min at 4°C and then 10,000 × g for 10 min. The pellet (mitochondrial fraction) was resuspended in a buffer containing 0.6 M mannitol, 20 mM HEPES-KOH at pH 7.4, 1 mM EGTA, and 2 g liter−1 bovine serum albumin (BSA) at approximately 10 g liter−1 of protein. The quality of mitochondria was evaluated by measuring the respiratory control ratio (RCR), as follows: (respiratory rate + ADP)/(respiratory rate − ADP).

The protein content was determined using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad).

Measurement of oxygen consumption.

The respirometric measurements on intact cells were performed with a Hansatech oxygraph (Hansatech Instruments Ltd., United Kingdom) as described previously (1). A total of 30 ml of cells was harvested from exponentially growing cultures at an OD600 of 0.7 to 1, centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and resuspended in minimal medium at a density of approximately 20 OD600 units. A total of 25 μl of this cell suspension was added to the oxygraphic chamber filled with 3 ml of defined medium containing the same carbon source used for growth, and oxygen consumption was followed. Triethyltin chloride (TET; Aldrich) at 15 μg cells (dry weight) mg−1 and carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP; Sigma) from 0.6 to 10 μM (the minimal amount adjusted for each strain and substrate to obtain the maximal respiration) were added directly to the cuvette, and the decrease in oxygen concentration was subsequently followed online. Respiratory rates (JO2 [basal oxygen uptake rate], Jmax [maximal {uncoupled} oxygen consumption rate], and JTET [mitochondrial respiration-independent oxygen consumption rate]) were determined from the slope of a plot of O2 concentration versus time divided by the biomass concentration. From these values, the respiratory state value (RSV) was calculated as described previously (1): RSV = (JO2 − JTET)/(Jmax − JTET).

Nucleotide content determination.

To determine mitochondrial NAD content, mitochondria were immediately subjected to acid and alkali extractions, followed by neutralization (12).

Total cellular NAD was extracted by the boiling buffered ethanol method (14). The alcoholic extract of about 20 ml of culture was dried at 40°C in a SpeedVac, resuspended in 400 μl of sterile ultrapure water, and subjected to acid and alkali treatments to destroy NADH and NAD+, respectively. All the extracts were neutralized with either 0.3 M HCl or 0.3 M NaOH and used for the determination of NAD+ and NADH, respectively, with the enzymatic cycling assay described in reference 12.

ATP was extracted using the boiling buffered ethanol procedure (14) and quantified using the luciferin-luciferase assay (ATP determination kit; Molecular Probes) and a Victor Luminometer (PerkinElmer), according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Statistical analysis.

All values are presented as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM). The statistical evaluation of the data was performed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni's post hoc tests, using the GraphPad InStat software, version 3.06. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Catabolite repression alleviates ndt1Δ ndt2Δ growth defects.

Deletion in an auxotrophic strain of the two specific mitochondrial NAD+ carriers, encoded by the NDT1 and NDT2 genes, resulted in a very low level of NAD+ in mitochondria, along with growth defects on nonfermentable carbon sources (27). To characterize the impact of NAD+ mitochondrial content on the cellular metabolism, we decided to use the prototrophic strain CEN.PK 113-7D, the model yeast strain generally used for qualitative and quantitative studies of central carbon and energy metabolism (28). In this genetic background, we generated an ndt1Δ ndt2Δ double deletion mutant and a strain, named ndt1-over, overexpressing NDT1, the gene coding for the main isoform of the NAD+ transporter (27). Western analyses using a polyclonal antibody raised against Ndt1 confirmed an increased amount of the carrier in the ndt1-over strain and the absence of any detectable signal in ndt1Δ ndt2Δ cells (data not shown).

When grown in batch culture on a defined glucose-based medium, the specific growth rate of the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain showed no significant differences from that of the wild type (WT) control strain (Table 1). High glucose concentrations typical of batch cultures are characterized by a strong repression of mitochondrial activity (15). Aiming to characterize the effect of catabolite repression on the physiology of the mutant strains, the specific growth rates achieved by the cells during growth on different fermentable or nonfermentable carbon sources were determined (Table 1). A statistically significant reduction in the specific growth rate of the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain was evident for cells growing on galactose (−10%) and raffinose (−30%). The differences in growth rate between the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain and the WT further increased when cells were grown on ethanol (−53%). These data indicate a deleterious effect of the NDT1 NDT2 double deletion, which seems to be dependent on the carbon source. Considering that the different carbon and energy sources used determine different levels of catabolite repression (11, 15), these results indicate that the degree of mitochondrial repression (glucose ≫ galactose > raffinose > ethanol) is inversely correlated with the growth rate of the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain. In contrast, for any carbon source assayed, the ndt1-over strain showed no appreciable changes compared to the WT (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Specific growth rates for the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ and ndt1-over strains on defined media supplemented with different carbon sources

| Strain | Specific growth rate (h−1) with carbon sourcea: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Galactose | Raffinose | Ethanol | |

| WT | 0.45 ± 0.015 | 0.20 ± 0.010 | 0.33 ± 0.016 | 0.13 ± 0.003 |

| Carrying ndt1Δ ndt2Δ | 0.42 ± 0.013 | 0.18 ± 0.008b | 0.24 ± 0.012b | 0.06 ± 0.002b |

| ndt1-over | 0.46 ± 0.014 | 0.20 ± 0.009 | 0.34 ± 0.015 | 0.13 ± 0.004 |

The data shown are means ± SEM resulting from at least three independent experiments.

Significant differences between the WT and the two mutant strains are indicated. P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test.

Cellular NAD content is dependent on the carbon source and the expression level of the mitochondrial NAD+ carriers.

Since carbon sources modulate the specific growth rates of the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain and strain ndt1-over in different ways, we measured the cellular NAD contents for the two mutants and for the WT strain growing on glucose and ethanol, with the growth conditions apparently causing the minimum perturbations and maximum biases, respectively. Cellular metabolites were extracted from cells collected during the exponential growth phase using the boiling buffered ethanol method (14), which provides for the quantitative extraction of the main cellular metabolites and moreover instantaneously inactivates the cellular metabolism.

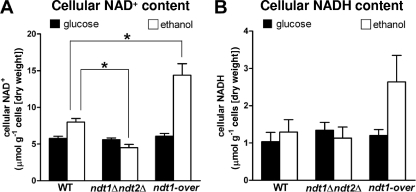

For cells grown on glucose, no significant differences in cellular NAD+ and NADH contents between the mutants and the control strain were observed. In particular, approximately 5.8 μmol NAD+ g−1 cells (dry weight) was measured for all the strains (Fig. 1 A), confirming previously published data (2). In fact, assuming a cellular volume of 2.38 ml per gram cells (dry weight) (25), our measurements correspond to a NAD+ concentration of 2.4 mM. Also, NADH content in the three strains was similar, with an average of 1.2 μmol NADH g−1 cells (dry weight) (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

NAD+ (A) and NADH (B) cellular contents (μmol g−1 cells [dry weight]) of the WT, ndt1Δ ndt2Δ, and ndt1-over strains harvested during exponential growth phase on glucose-based media (black bars) or ethanol-based media (open bars). The data shown are means ± SEM from at least three independent measurements carried out using three independent preparations. The significance of the differences between the WT and the two mutant strains is indicated (*, P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test).

For WT cells grown on ethanol, a marked increase (of about 37%) in the cellular NAD+ concentration was measured compared with that of the same cells grown on glucose (Fig. 1A). Differences in NAD+ concentrations found in glucose and ethanol are probably related to the different involvements of respiration and mitochondrial biogenesis under the two conditions.

In the ethanol-grown ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain, the NAD+ concentration was significantly (P < 0.05) lower (−44%) than that of the WT (Fig. 1A).

In contrast, NDT1 overexpression caused a strong increase in the levels of both of the coenzymes (Fig. 1A and B), resulting in a total NAD concentration that was 2-fold higher than that of WT cells growing under the same conditions. Since ndt1-over and the WT had the same growth rate (Table 1), it follows that overexpression of the Ndt1 transporter and the increase in cellular NAD concentration did not affect the growth efficiency on ethanol.

Alterations in expression of NDT1 and NDT2 affect the mitochondrial NAD content.

Growth on ethanol is characterized by a full respiratory metabolism, and the differences in cellular NAD contents displayed by the mutants could be dependent on a different subcellular compartmentalization of the nucleotide. Therefore, mitochondria from cells grown on ethanol to mid-log phase were isolated, and the amounts of mitochondrial NAD+ and NADH were determined.

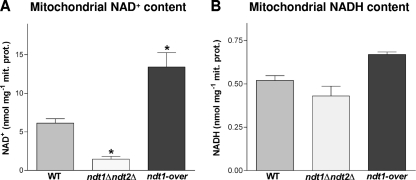

Although devoid of the only two specific mitochondrial NAD+ carriers identified so far, the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain grown on ethanol showed residual mitochondrial NAD+ content (1.5 nmol mg−1 protein) (Fig. 2 A), a concentration 4-fold lower than that observed in the WT (6.1 nmol mg−1 protein) (Fig. 2A), in line with previously reported data for a different auxotrophic strain (27). Since similar mitochondrial NADH levels for the double deletion and WT strains have been measured (Fig. 2B), it follows that the mitochondrial NAD+/NADH ratio of the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain was almost 4 times lower than that of the WT.

FIG. 2.

NAD+ (A) and NADH (B) contents of mitochondria isolated from the WT, ndt1Δ ndt2Δ, and ndt1-over strains. Mitochondria were isolated from batch cultures exponentially growing on ethanol. The data shown are means ± SEM from six independent determinations carried out using three independent mitochondrial preparations. The significance of the differences between the WT and the two mutant strains is indicated (*, P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test). mit. prot., mitochondrial protein.

Conversely, mitochondria extracted from ethanol-grown ndt1-over cells showed a doubling of the NAD+ concentration (13.4 nmol mg−1 protein) (Fig. 2A) compared to that of the WT. Although the coenzyme availability had increased, the mitochondrial NADH content measured in the ndt1-over strain was similar to that of the WT (Fig. 2B).

These findings indicate a correlation between the levels of Ndt1/Ndt2 and the mitochondrial NAD concentration, which on ethanol resulted in 4-fold-lower and 2-fold-higher levels for the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ and ndt1-over strains, respectively.

The level of mitochondrial NAD modulates the maximum oxygen consumption rate of the cells.

To better characterize the consequences of altered NAD content on the oxidative properties of yeast cells, we measured the oxygen consumption rates of cells grown on defined medium supplemented with either glucose or ethanol. Exponentially growing cells were first harvested and then resuspended in a fresh medium supplemented with the same carbon source at the same concentration used for the growth, and the basal oxygen uptake rate (JO2) was determined. Treatments with TET (15 μg cells [dry weight] mg−1), a lipophilic FoF1-ATPase inhibitor (7), and a common protonophore such as CCCP allowed the determination of the nonphosphorylating respiration rate (JTET) and the maximal (uncoupled) oxygen consumption rate (Jmax), respectively. From these values, the respiratory state value [RSV = (JO2 − JTET)/(Jmax − JTET)] was calculated. RSV is a measure of the oxidative phosphorylation efficiency. It gives more accurate information than the JO2/Jmax ratio, as it rules out the contribution of the nonphosphorylating respiration (JTET).

When cells were grown on glucose (Table 2), ndt1Δ ndt2Δ and ndt1-over cells showed no significant difference from the WT in terms of basal oxygen uptake (JO2). All strains respired at about 45% of their ATP synthesis-coupled maximal oxygen uptake rate, and all the respiratory parameters were similar.

TABLE 2.

Respiratory parameters of cells batch grown on glucosea

| Strain | JO2 | JTET | Jmax | Jmax/JTET | JO2/Jmax | RSV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 67.5 ± 3.5 | 35.6 ± 1.4 | 106.1 ± 5.7 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 0.64 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.01 |

| Carrying ndt1Δ ndt2Δ | 75.0 ± 3.6 | 40.4 ± 3.1 | 113.6 ± 7.6 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 0.66 ± 0.01 | 0.47 ± 0.03 |

| ndt1-over | 61.9 ± 2.1 | 37.3 ± 0.9 | 99.4 ± 7.7 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.40 ± 0.05 |

Oxygen uptake rates (J) are measured in nmol O2min−1 mg−1 cells (dry weight). The RSV definition and substrate and inhibitor concentrations are detailed in the text. The data shown are means ± SEM resulting from at least three independent experiments. The differences between the WT and the two mutant strains are not significant (P > 0.05; one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test).

Differences in the mitochondrial NAD concentration affected respiratory parameters when cells were grown under completely respiratory growth conditions such as on ethanol (Table 3). In good agreement with its low growth rate, the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain showed a 40% decrease in its basal oxygen uptake rate compared to that of the WT. Remarkably, under this condition, the double deletion strain modulated its efficiency in coupling ADP phosphorylation to respiration, since the contribution of (JTET) was very low. As a consequence, the RSV for ndt1Δ ndt2Δ cells was greater than that value for the WT (+77%), suggesting that cells consumed oxygen closer to their upper physiological limit.

TABLE 3.

Respiratory parameters of cells batch grown on ethanola

| Strain | JO2 | JTET | Jmax | Jmax/JTET | JO2/JMAX | RSV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 101.5 ± 3.9 | 60.9 ± 5.7 | 210.9 ± 6.1 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 0.27 ± 0.02 |

| Carrying ndt1Δ ndt2Δ | 62.7 ± 6.2b | 28.4 ± 3.5b | 100.3 ± 6.3b | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.04b |

| ndt1-over | 92.2 ± 2.7 | 61.9 ± 4.8 | 240.7 ± 10.2b | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 0.38 ± 0.02b | 0.17 ± 0.02b |

Oxygen uptake rates (J) are measured in nmol O2min−1 mg−1 cells (dry weight). The RSV definition and substrate and inhibitor concentrations are detailed in the text. The data shown are means ± SEM resulting from at least three independent experiments.

Significant differences between the WT and the two mutant strains are indicated (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test).

The respiratory parameters for the ndt1-over strain were very similar to those of the WT, with the only exception being Jmax, which reached a value of more than 240 nmol O2 min−1mg−1 cells (dry weight), corresponding to a 14% increase in the maximum oxygen uptake rate compared to that of the WT. Consequently, its RSV was the lowest measured, being about 63% of the control.

For cells oxidizing ethanol, only derepressed oxygen uptake rates (Jmax) and RSV showed a direct and an inverse correlation, respectively, with NAD mitochondrial content. However, while the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain was not able to increase its oxygen consumption rate and had to rely on a better coupling of respiration and phosphorylation, a potentially higher Jmax value was not advantageous for the growth of ndt1-over cells. This strain displayed partially blocked oxidative phosphorylation and the same growth rate as that of the WT cells.

The above-described considerations were further confirmed by ATP determinations. The results given in Table 4 show the influence of mitochondrial NAD availability on cellular ATP concentration. Again, under respirofermentative conditions (glucose), the three strains displayed no significant differences. Instead, a decrease in cellular ATP for both the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ (−46%) and the ndt1-over (−28%) strains, when cells were grown on ethanol, was shown.

TABLE 4.

Cellular ATP contents of cells batch grown on glucose or ethanol

| Strain | ATP (μmol g−1 cells [dry weight])a |

|

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Ethanol | |

| WT | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 6.2 ± 0.6 |

| Carrying ndt1Δ ndt2Δ | 7.7 ± 1.5 | 3.3 ± 0.5b |

| ndt1-over | 7.3 ± 1.6 | 4.3 ± 0.5b |

The data shown are means ± SEM resulting from at least four independent determinations.

Significant differences between the WT and the two mutant strains are indicated (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test).

In a glucose-limited chemostat, ndt1-over strain behavior is similar to that of the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ mutant.

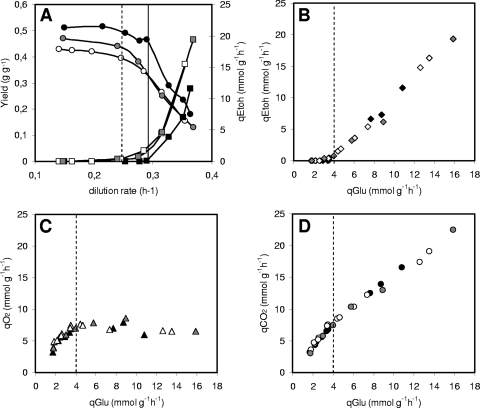

In order to better compare and define the metabolic consequences of an alteration in mitochondrial NAD+ transport, we analyzed the behavior of the strains during growth in continuous glucose-limited experiments. The use of the chemostat technique makes it easy to manipulate the specific growth of cells without any other change in the cultural conditions used. Moreover, since the residual glucose concentration in the bioreactor for almost any physiological growth condition is very low, the catabolite repression effect is drastically reduced (4). The experiments covered an interval of growth rates (dilution rates) ranging from 0.15 h−1 to nearly 0.37 h−1 (Fig. 3). In glucose-limited chemostat cultures, at least two well-defined cellular metabolisms can be analyzed: a merely respiratory metabolism (at a low dilution rate), similar to that of batch cells growing on ethanol, and a mixed respirofermentative metabolism (at higher dilution rates), somehow recalling batch growth on glucose with ethanol production.

FIG. 3.

Behavior of the main physiological parameters for the WT (closed symbols), ndt1Δ ndt2Δ (open symbols), and ndt1-over (gray symbols) yeast strains during continuous glucose-limited growth. (A) Variation of biomass yields and specific ethanol production rates. Critical dilution rates are reported for the WT (solid line) and mutants (dotted line). (B) Specific ethanol production rate versus specific glucose consumption rate. The dotted line marks the critical glucose consumption rate (see text). (C) Specific oxygen consumption rate versus specific glucose consumption rate. The dotted line marks the critical glucose consumption rate. (D) Specific carbon dioxide production rate versus specific glucose consumption rate. The dotted line marks the critical glucose consumption rate.

The behavior of the physiological parameters for the WT strain showed the typical pattern of a Crabtree-positive yeast. At low dilution rates, given that the metabolism is fully respiratory, a high biomass yield was observed (0.51 g g−1) (Fig. 3A); biomass and carbon dioxide were the only products. When the dilution rate increased above the critical dilution rate value of 0.28 h−1, the metabolism became respirofermentative, and ethanol production took place; as a consequence, the biomass yield value decreased.

The deletion of NDT1 and NDT2 or overexpression of NDT1 determined similar behaviors, which differed from those of the WT strain. In particular, for any dilution rate analyzed, the biomass yield values measured were lower than those of the WT control strain. Furthermore, the critical dilution rate values for both the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ and ndt1-over strains also settled at lower values (Fig. 3A). Notwithstanding the low biomass yield(s), the mutant strains consumed all the glucose available, since the residual glucose was barely detectable at only high dilution rates. As a consequence, the specific glucose consumption rates (qGlu; mmol g−1 h−1) calculated for the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ and the ndt1-over strains were always higher than the value determined for the WT strain at the same dilution rate (data not shown). In this respect, an interesting observation came by plotting the values of the specific ethanol consumption rates (qEtoh) for the three strains against their qGlu values (Fig. 3B). Irrespective of the strain analyzed, a clear shift from a merely oxidative metabolism to a respirofermentative metabolism with ethanol production was observed for cells having the same qGlu value (about 4 mmol g−1 h−1). Furthermore, there was a very similar trend at higher qGlu values (Fig. 3B).

A further indication that specific ethanol production for all strains took place via the same mechanisms came by analyzing the trends of the oxygen consumption rate (qO2; mmol g−1 h−1) versus those of the qGlu (Fig. 3C). All the strains increased their respiration rate until the critical specific glucose uptake value of 4 mmol g−1 h−1 of glucose consumed was reached. Beyond this critical value, no further increase was observed. Finally, specific carbon dioxide production (specific CO2 consumption rate [qCO2]; mmol g−1h−1) was consistent with the above-described data, again showing no differences between the three strains (Fig. 3D).

DISCUSSION

NAD+ and NADH are among the main control players of cellular metabolism, since they are involved in many important reactions (10). Indeed, the effects of changes on NAD+ and NADH cellular concentrations as well as on the NAD+/NADH ratio have been investigated in many metabolic engineering studies. In this context, Escherichia coli and S. cerevisiae are the prokaryotic and eukaryotic model organisms generally studied, respectively. For example, in E. coli, the production of acetic acid and the ethanol-to-acetate ratio are influenced by the cellular NAD+/NADH ratio and by NADH availability (3, 31). Also, in S. cerevisiae, recent studies have focused on the metabolic consequences of an alteration in the NAD+/NADH ratio either in the cytosol or in the mitochondria, resulting in dramatic alterations in biomass yield, ethanol, and glycerol accumulation (18, 19, 32).

In the present paper, we show that modifications in expression of the mitochondrial NAD+ carriers, encoded by the NDT1 and NDT2 genes, drastically change the NAD concentration in the mitochondria and in the whole cell. Two prototrophic strains, one carrying a double deletion (ndt1Δ ndt2Δ) and the other carrying the NDT1 gene, coding for the main isoform of the NAD+ transporter, under the control of a strong constitutive promoter (ndt1-over) were constructed. Strain characterization was carried out by analyzing cells growing with an oxidative or respirofermentative metabolism in batch and glucose-limited chemostat cultures, yielding complementary results.

When considering the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain during batch growth, at least three main features should be underlined. First, the growth rate of the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain seems to be directly dependent on the degree of catabolite repression imposed by the carbon source used (Table 1). Second, a comparative analysis with control WT cells shows that cells growing on ethanol had lower levels of mitochondrial NAD+ (Fig. 2A) and cellular ATP (about 50% lower) (Table 4). Third, the respiration rate of the double deletion strain on ethanol, although lower than that of the WT, is close to its upper physiological limit and more efficient (Table 3). We might speculate that in ndt1Δ ndt2Δ cells growing on ethanol with fully respiratory metabolism, a low mitochondrial NAD+ content and/or a low NAD+/NADH ratio could impair oxidative phosphorylation, causing a decrease in ATP concentration that could result in a low growth rate. Indeed, evidence of a kinetic control of dehydrogenases, such as pyruvate dehydrogenase, has been reported (21). In fact, this enzyme activity is competitively inhibited by NADH with NAD+. Moreover, reduced acetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity (27) can limit the ethanol oxidation rate of the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ strain (5).

According to the near-equilibrium hypothesis (9), the whole of oxidative phosphorylation from mitochondrial NADH to cytosolic ATP usually operates near equilibrium apart from cytochrome oxidase, which is far from equilibrium. Consequently, modification of the mitochondrial NAD+ and/or NADH concentration can influence the rate of respiration. A mitochondrial redox potential, which is more reducing than that of the WT (due to the low NAD+ concentration, the mitochondrial NAD+/NADH ratio of the ndt1Δ ndt2Δ cells is 4-fold lower), can explain the higher respiratory efficiency showed by this strain. We can exclude the contribution of an alternative oxidase to the high RSV measured, since this protein is absent in S. cerevisiae (30).

In ndt1-over cells growing on ethanol, overexpression of the Ndt1 transporter led to higher mitochondrial and cellular NAD+ and (although to a lesser extent) NADH concentrations. Surprisingly, this resulted in a slightly but significantly lower cellular ATP concentration (30% lower than that of the WT) (Table 4) and a lower respiratory efficiency level (Table 3). It should be emphasized that the specific growth rates of the control and ndt1-over strains are quite similar during batch growth on the different carbon sources (Table 1).

In line with the near-equilibrium hypothesis (9), the decrease in mitochondrial efficiency of the ndt1-over strain could be ascribed to the mitochondrial NAD+/NADH ratio, which is 1.7-fold higher than that of the WT. Thus, the lower oxidative phosphorylation efficiency may be caused by a mass action effect, since the mitochondrial redox potential of this strain is more oxidized. An additional explanation for ndt1-over's bioenergetic inefficiency may be that NAD+ or NADH exerts a possible allosteric effect on a component of the respiratory chain. Using a simple stoichiometric model to estimate the oxidative phosphorylation efficiency, Hou et al. (18) have proposed that an increase in mitochondrial NADH inhibits ATP synthesis and that an optimal mitochondrial redox level is needed to achieve efficient oxidative phosphorylation.

Finally, in order to better understand the behavior of the mutant strains, cells were grown in glucose-limited chemostat cultures under well-defined physiological conditions. During continuous growth below the critical dilution rate, the metabolism of cells is fully respiratory and requires sustained mitochondrial respiration. At the critical dilution rate value, a clear switch from a fully respiratory to a respirofermentative metabolism takes place with ethanol production.

Assuming identical biomass compositions, the low biomass yield values observed for both mutant strains (Fig. 3A) are indicative of lower bioenergetic efficiency levels: both ndt1Δ ndt2Δ and ndt1-over cells consumed more glucose than the WT cells to produce the same amount of biomass. This observation agrees perfectly with the cellular ATP concentration of cells growing with a fully respiratory metabolism (batch growth on ethanol) (compare ATP data shown in Table 4 and biomass yields shown in Fig. 3A). Differences between WT and mutant strains progressively decreased for cells growing with higher dilution rates (Fig. 3A), suggesting once again that none of the mutant strains displayed any disadvantage during growth with a respirofermentative metabolism.

An important observation comes from the analysis of the results shown in Fig. 3B, where it is evident that all the strains switched their metabolisms (from fully respiratory to respirofermentative ones) at the same specific glucose flux. This seems to indicate that the specific glucose uptake rate and/or the glycolytic flux should be considered among the most important independent variables for establishing the long-term Crabtree effect for both WT cells and cells with altered NAD+ transport into mitochondria. In addition, oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production trends for all the strains overlap (Fig. 3C and D). Since the three strains can sustain oxygen consumption to the same extent, it appears that ethanol production is not dependent on mitochondrial NAD content. Instead, the Crabtree effect seems to be triggered by saturation of the cellular capacity for pyruvate respiration, which causes a redistribution in pyruvate flux toward ethanol production. On this topic, data in the literature are quite discordant. Among other hypotheses, competition between pyruvate decarboxylase and mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase has been proposed as a possible cause of the Crabtree effect (17, 29). We also proposed a critical cytoplasmic NADH concentration as a cause of the Crabtree effect (24). More recent papers point to the importance of the mitochondrial NAD+/NADH balance in triggering this phenomenon (18, 32). Additional investigations are required to better clarify this complex effect.

To sum up, we modulated the mitochondrial NAD content in yeast. Both an increase and a decrease in pyridine nucleotide impaired mitochondrial activity and reduced cellular ATP content under fully respiratory conditions. In this respect, our data obtained from glucose-limited chemostat cultures provided new insights. Collectively, our data suggest that an optimal mitochondrial NAD concentration is needed to achieve optimal bioenergetic efficiency. We believe that such studies will be useful, since cofactor engineering is becoming a successful strategy to manipulate metabolic fluxes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anthony Green for kindly reviewing the English in the manuscript.

This work was partially supported by grants FAR 2008 and FAR 2009 to D.P.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilaniu, H., L. Gustafsson, M. Rigoulet, and T. Nyström. 2001. Protein oxidation in G0 cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae depends on the state rather than rate of respiration and is enhanced in pos9 but not yap1 mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 276:35396-35404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belenky, P., et al. 2007. Nicotinamide riboside promotes Sir2 silencing and extends lifespan via Nrk and Urh1/Pnp1/Meu1 pathways to NAD+. Cell 129:473-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berríos-Rivera, S., K.-Y. San, and G. N. Bennet. 2002. The effect of NAPRTase overexpression on the total levels of NAD, the NADH/NAD+ ratio, and the distribution of metabolites in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 4:238-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boer, V. M., J. H. de Winde, J. T. Pronk, and M. D. Piper. 2003. The genome-wide transcriptional responses of Saccharomyces cerevisiae grown on glucose in aerobic chemostat cultures limited for carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, or sulfur. J. Biol. Chem. 278:3265-3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boubekeur, S., N. Camougrand, O. Bunoust, M. Rigoulet, and B. Guérin. 2001. Participation of acetaldehyde dehydrogenases in ethanol and pyruvate metabolism of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:5057-5065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourguignon, J., M. Neuburger, and R. Douce. 1988. Resolution and characterization of the glycine-cleavage reaction in pea leaf mitochondria. Properties of the forward reaction catalysed by glycine decarboxylase and serine hydroxymethyltransferase. Biochem. J. 255:169-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cain, K., and D. E. Griffiths. 1977. Studies of energy-linked reactions. Localization of the site of action of trialkyltin in yeast mitochondria. Biochem. J. 162:575-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Lisa, F., and M. Ziegler. 2001. Pathophysiological relevance of mitochondria in NAD(+) metabolism. FEBS Lett. 492:4-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erecińska, M., and D. F. Wilson. 1982. Regulation of cellular energy metabolism. J. Membr. Biol. 70:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Förster, J., I. Famili, P. Fu, B. O. Palsson, and J. Nielsen. 2003. Genome-scale reconstruction of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae metabolic network. Genome Res. 13:244-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gancedo, J. M. 1998. Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:334-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibon, Y., and F. Larher. 1997. Cycling assay for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides: NaCl precipitation and ethanol solubilization of the reduced tetrazolium. Anal. Biochem. 251:153-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein, A. L., and J. H. McCusker. 1999. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15:1541-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez, B., J. François, and M. Renaud. 1997. A rapid and reliable method for metabolite extraction in yeast using boiling buffered ethanol. Yeast 13:1347-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrero, P., R. Fernández, and F. Moreno. 1985. Differential sensitivities to glucose and galactose repression of gluconeogenic and respiratory enzymes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch. Microbiol. 143:216-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirosawa, I., et al. 2004. Construction of a self-cloning sake yeast that overexpresses alcohol acetyltransferase gene by a two-step gene replacement protocol. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 65:68-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holzer, H. 1961. Regulation of carbohydrate metabolism by enzyme competition. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 26:277-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou, J., N. F. Lages, M. Oldiges, and G. N. Vemuri. 2009. Metabolic impact of redox cofactor perturbations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab. Eng. 11:253-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou, J., and G. N. Vemuri. 2010. Using regulatory information to manipulate glycerol metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85:1123-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Igamberdiev, A. U., and P. Gardeström. 2003. Regulation of NAD- and NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenases by reduction levels of pyridine nucleotides in mitochondria and cytosol of pea leaves. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1606:117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kresze, G. B., and H. Ronft. 1981. Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from baker's yeast. 1. Purification and some kinetic and regulatory properties. Eur. J. Biochem. 119:573-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin, S. J., P. A. Defossez, and L. Guarente. 2000. Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for lifespan extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 289:2126-2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmieri, F., et al. 2009. Molecular identification and functional characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana mitochondrial and chloroplastic NAD+ carrier proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 284:31249-31259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porro, D., L. Brambilla, and L. Alberghina. 2003. Glucose metabolism and cell size in continuous cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 229:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Theobald, U., W. Mailinger, M. Baltes, M. Rizzi, and M. Reuss. 1997. In vivo analysis of metabolic dynamics in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. I. Experimental observations. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 55:305-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tobin, A., B. Djerdjour, E. Journet, M. Neuburger, and R. Douce. 1980. Effect of NAD on malate oxidation in intact plant mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 66:225-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todisco, S., G. Agrimi, A. Castegna, and F. Palmieri. 2006. Identification of the mitochondrial NAD+ transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 281:1524-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Dijken, J. P., et al. 2000. An interlaboratory comparison of physiological and genetic properties of four Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 26:706-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Hoek, P., et al. 1998. Effects of pyruvate decarboxylase overproduction on flux distribution at the pyruvate branch point in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2133-2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Veiga, A., J. Arrabaca, and M. Loureirodias. 2003. Cyanide-resistant respiration, a very frequent metabolic pathway in yeasts. FEMS Yeast Res. 3:239-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vemuri, G. N., E. Altman, D. P. Sangurdekar, A. B. Khodursky, and M. A. Eiteman. 2006. Overflow metabolism in Escherichia coli during steady-state growth: transcriptional regulation and effect of the redox ratio. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3653-3661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vemuri, G. N., M. A. Eiteman, J. E. McEwen, L. Olsson, and J. Nielsen. 2007. Increasing NADH oxidation reduces overflow metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:2402-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verduyn, C., E. Postma, W. A. Scheffers, and J. P. Van Dijken. 1992. Effect of benzoic acid on metabolic fluxes in yeasts: a continuous-culture study on the regulation of respiration and alcoholic fermentation. Yeast 8:501-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu, F., F. Yang, K. C. Vinnakota, and D. A. Beard. 2007. Computer modeling of mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, metabolite transport, and electrophysiology. J. Biol. Chem. 282:24525-24537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang, H., et al. 2007. Nutrient-sensitive mitochondrial NAD+ levels dictate cell survival. Cell 130:1095-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziegler, M. 2000. New functions of a long-known molecule. Emerging roles of NAD in cellular signaling. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:1550-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]