Abstract

The genome of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete, encodes a homolog (the bb0184 gene product) of the carbon storage regulator A protein (CsrABb); recent studies reported that CsrABb is involved in the regulation of several infectivity factors of B. burgdorferi. However, the mechanism involved remains unknown. In this report, a csrABb mutant was constructed and complemented in an infectious B31A3 strain. Subsequent animal studies showed that the mutant failed to establish an infection in mice, highlighting that CsrABb is required for the infectivity of B. burgdorferi. Western blot analyses revealed that the virulence-associated factors OspC, DbpB, and DbpA were attenuated in the csrABb mutant. The Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway (σ54-σS sigma factor cascade) is a central regulon that governs the expression of ospC, dbpB, and dbpA. Further analyses found that the level of RpoS was significantly decreased in the mutant, while the level of Rrp2 remained unchanged. A recent study reported that the overexpression of BB0589, a phosphate acetyl-transferase (Pta) that converts acetyl-phosphate to acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA), led to the inhibition of RpoS and OspC expression, suggesting that acetyl-phosphate is an activator of Rrp2. Along with this report, we found that CsrABb binds to the leader sequence of the bb0589 transcript and that the intracellular level of acetyl-CoA in the csrABb mutant was significantly increased compared to that of the wild type, suggesting that more acetyl-phosphate was being converted to acetyl-CoA in the mutant. Collectively, these results suggest that CsrABb may influence the infectivity of B. burgdorferi via regulation of acetate metabolism and subsequent activation of the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway.

Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme borreliosis, has a complex natural enzootic life cycle—transmitting between Ixodes tick vectors and mammals (56, 57). As such, differential gene expression plays an important role in its adaptation to diverse host environments (10, 45). To date, a limited number of regulatory pathways have been identified in B. burgdorferi (13, 16, 23, 34, 38, 46, 66). Among these identified regulatory factors, the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway is a central regulatory network of B. burgdorferi, which consists of a two-component response regulator, Rrp2, and two alternative sigma factors, RpoN (σ54) and RpoS (σS) (11, 23, 66). In this pathway, Rrp2 acts in concert with RpoN to directly modulate the level of RpoS, which in turn governs the expression of more than 10% of B. burgdorferi genes, including those encoding several infection-associated factors, such as the outer membrane surface lipoprotein C (OspC), decorin binding proteins A and B (DbpB and DbpA), and fibronectin-binding protein BBK32 (13, 66). RpoS is a key component in this regulatory cascade. In addition to Rrp2, recent studies showed that B. burgdorferi DsrA (DsrABb) (a small noncoding RNA) and BosR (a homolog of the Fur regulatory protein) are also the regulators of RpoS (24, 34, 38).

The carbon storage regulator (Csr) system was first discovered in Escherichia coli and has subsequently been shown to be well conserved in many different bacterial species (3, 48). Csr is a global regulatory system which typically exerts its regulation on gene expression at the posttranscriptional level (47, 48). The E. coli Csr system consists of a key determinant, CsrA (an RNA binding protein), two noncoding regulatory RNAs (CsrB and CsrC), and a regulatory protein CsrD (4, 32, 58). Both CsrB and CsrC antagonize the activity of CsrA, whereas CsrD targets the two regulatory RNAs for degradation by RNase E. CsrA binds to the targeted transcripts at a consensus sequence. This binding can result in either enhanced translation of a gene via stabilization of its transcript or repression by blocking the ribosome binding site, leading to rapid degradation of the targeted mRNAs. A body of studies has shown that the Csr system plays a very important role in the regulation of bacterial carbon metabolism, motility, biofilm formation, and virulence (1, 25, 27, 28, 37, 40, 48, 64). For instance, in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, CsrA acts as both the positive and negative regulator for the expression of virulence genes in the pathogenicity island SPI1, which encodes the components for the assembling of the type III secretion system. Altier et al. described that both repression and overexpression of csrA can lead to the attenuation of virulence factors encoded by SPI1, highlighting the importance of CsrA in the regulation of virulence (1, 27). In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, RsmA (a homolog of CsrA) regulates the expression of virulence factors that are required for an acute infection (37, 40).

CsrABb (the bb0184 gene product), a homolog of CsrA, was recently identified in B. burgdorferi (51). It was found that the overexpression of csrABb led to altered cell morphology, motility, and antigen profiles of B. burgdorferi, suggesting that CsrABb may be an important regulator of B. burgdorferi. However, the potential mechanism involved and the possible role of CsrABb in the pathogenesis of B. burgdorferi remain unclear. In this report, a csrABb mutant was constructed and genetically complemented in B31A3, a low-passage virulent strain of B. burgdorferi, and the resulting strains were tested in animal models. In addition, the influence of CsrABb on the expression of OspA, OspC, DbpB, DbpA, RpoS, and other regulatory proteins was examined, and the potential mechanism involved was investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto B31A3 (a low-passage virulent clone) and B31A (a high-passage avirulent clone) were used in this study (15, 30, 50). Cells were maintained at 34°C in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK-II) medium in the presence of 3.4% carbon dioxide. The strains were grown in the appropriate antibiotic(s) for selective pressure as needed: kanamycin (300 μg/ml) and/or gentamicin (40 μg/ml). The E. coli TOP10 strain (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used for DNA cloning, and the BL21 Codon Plus strain (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used for the expression of the recombinant protein. The E. coli strains were cultured in lysogeny broth (LB) supplemented with appropriate concentrations of antibiotics.

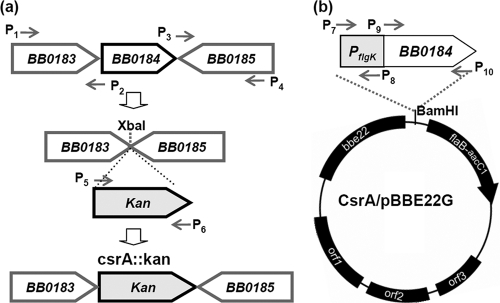

Constructing csrA::kan and CsrA/pBBE22G plasmids.

The csrA::kan plasmid was constructed for the targeted mutagenesis of csrABb (bb0184), and the plasmid CsrA/pBBE22G for the complementation of the mutant. To construct the csrA::kan plasmid, the flanking regions of bb0184 and the kanamycin resistance gene (kan) were amplified by PCR using primers P1/P2, P3/P4, and P5/P6 (Table 1). The resulting PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T-easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI). The upstream and downstream regions were ligated. Then, the kan cassette was inserted into the obtained fragment at an engineered XbaI cut site, generating the csrA::kan plasmid in which the entire open reading frame (ORF) of bb0184 was deleted (Fig. 1). To construct the plasmid CsrA/pBBE22G, the full length of bb0184 and the flgK promoter (PflgK) were PCR amplified with primers P7/P8 and P9/P10 (Table 1), and the resulting fragments were fused at an engineered NdeI cut site. PflgK is a σ70-like promoter located upstream of the flgK operon where the bb0184 gene is located (17). The obtained PflgKBB0184 fragment was then cloned into the shuttle vector pBBE22G (63), yielding the plasmid CsrA/pBBE22G.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers and the RNA probe used in this studya

| Primer | Description | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | Upstream of csrABb (F) | 5′-CGTTGCAAAAATCAATGAATC-3′ |

| P2 | Upstream of csrABb (R) | 5′-TCTAGATGATTGGTGCCTTTAGGTTAG-3′ |

| P3 | Downstream of csrABb (F) | 5′-TCTAGATAACCTCTGCATTTTGTC-3′ |

| P4 | Downstream of csrABb (R) | 5′-CATATGTTCTTTGGAAGAATTTGAGC-3′ |

| P5 | Kan (F) | 5′-TCTAGATAATACCCGAGCTTCAAG-3′ |

| P6 | Kan (R) | 5′-TCTAGATCAAGTCAGCGTAATGCTCTG-3′ |

| P7 | Complementation, PflgK (F) | 5′-GGATCCGCACTACTTAAAAAAGGTGTTGC-3′ |

| P8 | Complementation, PflgK (R) | 5′-CATATGTTTTATGAAATTAATTATAAGC-3′ |

| P9 | Complementation, csrABb (F) | 5′-CATATGCTAGTATTGTCAAGAAAAGC-3′ |

| P10 | Complementation, csrABb (R) | 5′-GGATCCTTATTTGTCATCGTCGTCC-3′ |

| P11 | qRT-PCR, rpoS (F) | 5′-ACCTATCTCCTGCTCAGTATATAA-3′ |

| P12 | qRT-PCR, rpoS (R) | 5′-CAAGGGTAATTTCAGGGTTAAAAG-3′ |

| P13 | qRT-PCR, ospC (F) | 5′-TGTTACTGATGCTGATGCAA-3′ |

| P14 | qRT-PCR, ospC (R) | 5′-AAGCTCTTTAACTGAATTAGC-3′ |

| P15 | qRT-PCR, dbpA (F) | 5′-GGACTAACAGGAGCAACA-3′ |

| P16 | qRT-PCR, dbpA (R) | 5′-CACCACTACTTCCAGTTTC-3′ |

| P17 | qRT-PCR, ospA (F) | 5′-GCAGCCTTGACGAGAAAAACA-3′ |

| P18 | qRT-PCR, ospA (R) | 5′-CGCCTTCAAGTACTCCAGATCC-3′ |

| P19 | qRT-PCR, dsrA (F) | 5′-AATGAAGTTAGTGGGCGTTACTC-3′ |

| P20 | qRT-PCR, dsrA (R) | 5′-TTTTTTTGAATAGGGTCACCAG-3′ |

| P21 | qRT-PCR, eno (F) | 5′-AACAGGAATTAACGAGGCTG-3′ |

| P22 | qRT-PCR, eno (R) | 5′-AAATTGCATTAGCACCAAGC-3′ |

| P23 | qRT-PCR, bb0589 (F) | 5′-GAGTTTTAAAGGCAGCTATTGT-3′ |

| P24 | qRT-PCR, bb0589 (R) | 5′-CTTTGCTTCGTAACTCCCTA-3′ |

| P25 | Co-RT, bb0588 (F) | 5′-CTGCTTTCAATTCAGCCAAAG-3′ |

| P26 | Co-RT, bb0589 (R) | 5′-GCCTATCAAAATAATCGAATCTGC-3′ |

| P27 | rCsrABb (F) | 5′-CACCATGCTAGTATTGTCAAGAAAAG-3′ |

| P28 | rCsrABb (R) | 5′-ATTTTCATTCTTGAAATAATG-3′ |

| P29 | EMSA probe | 5′-UUUAUUAUAAGGAGUGUGAUUUU-3′ |

| P30 | EMSA probe (mutated) | 5′-UUUAUUAUAAAAAGUGUGAUUUU-3′ |

The underlined sequences are the engineered restriction cut sites for DNA cloning; the bold “GGA” in P29 is the essential binding site for CsrA (36), and it was mutated to “AAA” in P30. F, foward; R, reverse.

FIG. 1.

Construction of the plasmid csrA::kan (a) for the inactivation of csrABb and of CsrA/pBBE22G (b) for the complementation of the csrABb mutant. (a) To construct the csrA::kan plasmid, the flanking regions of bb0184 (csrABb) were amplified by PCR and ligated. The whole bb0184 gene was omitted and replaced with kan in the final construct. (b) PflgK, the flgK promoter upstream of bb0180 (17), was amplified by PCR and fused to the 5′ end of bb0184. The obtained fragment was further cloned into the shuttle vector pBBE22G (54).

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

B. burgdorferi cells were cultivated at 34°C/pH 7.6 and harvested at stationary phase (∼108 cells/ml). Equal amounts of whole-cell lysates (10 to 50 μg) were separated on an SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The immunoblots were probed with specific antibodies against OspA, OspC, DbpA, DbpB, RpoS, Rrp2, BosR, and DnaK (an internal control). These antibodies were kindly provided by F. T. Liang (Louisiana State University), X. F. Yang (Indiana University), and J. Skare (Texas A&M University). Immunoblots were developed using horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) luminol assay, as previously described (30).

Measuring growth rates of B. burgdorferi.

To measure the growth rates of B31A3 and the mutant, 5 μl of the stationary-phase cultures (1 × 108 cells/ml) was inoculated into 5 ml medium and incubated at 23°C/pH 7.6 or 37°C/pH 6.8. The bacterial concentrations of the cultures were measured every 12 h for up to 8 days using the Petroff Hausser counting chamber (6). Counts were repeated in triplicate with at least two independent samples, and the results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RNA preparation and qRT-PCR.

RNA isolation was performed as previously described (10, 49). Briefly, B. burgdorferi strains were cultivated at 37°C, and 50 ml of stationary-phase cultures (∼108 cells/ml) was harvested for RNA preparation. Total RNA was extracted using TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), following the manufacturer's instructions. The resultant samples were treated with Turbo DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX) at 37°C for 2 h to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. The resultant RNA samples were re-extracted using acid phenol-chloroform (Ambion), precipitated in isopropanol, and washed with 70% ethanol. The RNA pellets were resuspended in RNase-free water. cDNA was generated from the purified RNA (1 μg) using AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using iQ SYBR green supermix and a MyiQ thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). RNA of the enolase gene (eno, bb0337) was amplified and used as an internal control to normalize the qRT-PCR data, as described before (49). The results were expressed as the normalized difference of the threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) between the wild type and the csrABb mutant. The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table 1.

Purification of recombinant CsrABb.

The full length of the bb0184 gene was PCR amplified using primers P27/P28 (Table 1) and Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). The obtained PCR product was ligated into the pET101/D expression vector (Invitrogen), which generates a six-histidine tag at the C terminus of the recombinant protein. The resulting plasmid was then transformed into BL21 Codon Plus cells (Stratagene). The expression of the recombinant CsrABb protein was induced using 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG). The recombinant protein (rCsrABb) was purified at 4°C using HisTrap HP columns (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), as previously described (36). The final purified protein was dialyzed in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 25% glycerol, pH 7.5, at 4°C overnight. The purified rCsrABb was used for either immunization or an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). To produce an antiserum against CsrABb, rats were first immunized with 1 mg of the recombinant protein during a 1-month period and then boosted (100 μg per rat) twice at weeks 6 and 7. Upon sacrifice at week 8, the animals were terminally bled, and the serum samples were tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunoblotting, as previously described (29, 30).

EMSA.

RNA probes (Table 1) were commercially synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) and labeled using the BrightStar psoralen-biotin nonisotopic labeling kit (Ambion), according to the manufacturer's instructions. EMSA was carried out, as previously described, with minor modifications (36). Briefly, rCsrABb, biotin-labeled RNA (20 fM), 32.5 ng of yeast RNA, and 10 U RNasin RNase inhibitor (Promega) were included in 10 μl of reaction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, and 10% glycerol). To evaluate the specificity of the RNA-protein interaction, a probe without the CsrABb-binding consensus was included. The sequences of these two probes are listed in Table 1. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min to allow rCsrABb-RNA complex formation. Reactions were separated on 4 to 20% native polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad), and signals were developed using the BrightStar nonisotopic detection system (Ambion), following the manufacturer's instructions.

Luciferase reporter assay.

PflgK was cloned into a luciferase construct, pJSB161 (8), and the obtained construct was transformed into the B31A strain. For the luciferase assay, 105 B. burgdorferi cells were inoculated into 5 ml BSK-II medium and cultured under fed-tick conditions (37°C/pH 6.8) to obtain the maximal expression of CsrABb. The bacterial concentrations of the cultures were measured daily using the Petroff Hausser counting chamber prior to the preparation of the cell lysates. A commercial luciferase assay kit (Promega) was used in this study, and the assay was carried out according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Luciferase activity was measured using a Veritas microplate luminometer (Promega), and the data were expressed as relative luciferase units per 106 cells (RLU/106 cells).

Infection studies in mice.

Both BALB/c and BALB/c SCID mice at 4 to 6 weeks of age (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were used in the study, as described previously (30). All animal procedures were performed in compliance with the guidelines and with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Briefly, the mice were given a single subcutaneous injection of 105 spirochetes and sacrificed 3 weeks postinoculation. Tissues from ear, heart, and joint were harvested and placed into 2 ml BSK-II medium. The samples were incubated at 34°C and monitored for 2 to 3 weeks to microscopically check for the presence of spirochetes in the medium.

Quantification of intracellular acetyl-CoA level.

Cell extracts were prepared using the perchloric acid extraction as described, with minor modification (41). Briefly, 10 ml of stationary-phase cultures (∼108 cells/ml) was harvested and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cell pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of washing buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA), treated with 200 μl of 3 M ice-cold HClO4, and incubated on ice for 30 min. The mixture was centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant was neutralized with saturated KHCO3 and centrifuged as described above. The level of acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) in the cell extract was quantified using the PicoProbe acetyl-CoA assay kit (BioVision Research Products, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Experiments were repeated in triplicate using three independent samples. Results are expressed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

Isolation of the csrABb mutant and its csrABb complemented strain.

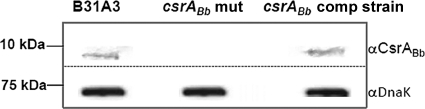

To inactivate bb0184, the csrA::kan vector was first linearized with SphI and then transformed into B31A3 (15) competent cells by electroporation (50). After 14 days of incubation, 63 kanamycin-resistant clones appeared on the agar plates. A previously described PCR analysis (29) showed that only 9 clones contain the expected targeted mutagenesis (data not shown). The plasmid profiles of these clones were detected by PCR, as described before (15, 18). Only one clone had the full plasmid content of its parental strain, B31A3, and this clone was named the csrABb mutant. Western blot analysis using an antiserum against CsrABb further confirmed that the cognate gene product was inhibited in the mutant. As shown in Fig. 2, a single band of an approximately 10-kDa protein was detected in B31A3 but not in the csrABb mutant.

FIG. 2.

Detection of CsrABb in the csrABb mutant (mut) and the csrABb complemented (comp) strain using Western blot analysis. The same amounts of B31A3, csrABb mutant, and csrABb complemented strain whole-cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. A specific antibody against CsrABb was produced and used for the Western blotting. DnaK was used as an internal control, as previously described (30). α, anti-.

The shuttle vector pBSV2G (59) was used initially to complement the csrABb mutant. After several attempts, we found that the obtained antibiotic-resistant clones lost either lp28-1 or lp25, two linear plasmids that are essential for the infectivity of B. burgdorferi (35, 43). To solve this problem, the shuttle vector pBBE22G was used to construct the plasmid CsrA/pBBE22G (Fig. 1) for the complementation. The vector pBBE22G contains a gentamicin-resistant marker (aacC1) and BBE22, a gene encoding a nicotinamidase that is required for the infectivity of B. burgdorferi in mice (42, 63). This vector has been used to restore infectivity when the lp25 plasmid is lost. Several clones with the complemented vector and the rest of the plasmids minus lp25 were isolated. One clone, the csrABb complemented strain, was chosen for further characterization. Western blotting showed that the csrABb complemented strain restored the expression of csrABb at a level similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 2).

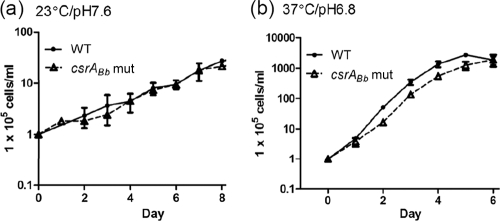

CsrABb is not essential for the growth of B. burgdorferi in vitro.

To determine if the csrABb gene influences the growth of B. burgdorferi, the growth rate of the csrABb mutant was measured under conditions mimicking both the arthropod vector (23°C/pH 7.6) and the mammalian host (37°C/pH 6.8) (53, 65). Under each condition, the mutant grew at the same rates as the wild type (Fig. 3), indicating that csrABb is not required for the growth of B. burgdorferi in vitro. In addition, Sanjuan et al. recently showed that the overexpression of csrABb altered the cell morphology and the motility of B. burgdorferi (51). We found that the csrABb mutant has a cell morphology and swimming behavior similar to those of the wild type (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

The growth curves of the wild type and the csrABb mutant. Growth curves were measured under the following conditions: 23°C/pH 7.6 (a) and 37°C/pH 6.8 (b). Cell counting was repeated in triplicate with at least two independent samples, and the results are expressed as mean ± SEM.

CsrABb is essential for the infectivity of B. burgdorferi.

To investigate the significance of csrABb in mammalian infectivity, BALB/c mice were infected intradermally with equal numbers of B31A3, the csrABb mutant, and the csrABb complemented strain (105 spirochetes per mouse). Tissues from the ear, heart, and joint were collected 21 days postinfection and transferred to BSK-II medium (30). Cultures were monitored for 2 to 3 weeks, and the infectivity was assessed via the presence of spirochete cells. As shown in Table 2, spirochetes were recovered from all tissue specimens of mice infected with B31A3 and approximately 80% of the tissues from mice infected with the complemented strain, whereas no spirochetes were recovered from any of the tissue specimens from mice infected with the mutant (Table 2). To determine if the failure of the mutant to establish an infection was due to the host adaptive immunity, a similar animal experiment was implemented using SCID mice (30). A similar phenotypic defect was observed, in that no spirochetes were recovered from any tissue specimens of mice infected with the mutant, indicating that CsrABb is required for the basic survival of B. burgdorferi in the murine host.

TABLE 2.

csrABb mutant was unable to infect micea

| B. burgdorferi strain | Mouse strain | No. of cultures positive/total no. of specimens examined |

No. of mice infected/total no. of mice used | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ear | Heart | Joint | All sites | |||

| B31A3 | BALB/c | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 12/12 | 4/4 |

| csrABb mutant | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/12 | 0/4 | |

| csrABb complemented strain | 3/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 11/12 | 4/4 | |

| B31A3 | SCID | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 9/9 | 3/3 |

| csrABb mutant | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/9 | 0/3 | |

| csrABb complemented strain | 2/3 | 3/3 | 2/3 | 7/9 | 3/3 | |

Groups of four BALB/c and three SCID mice were inoculated with 105 spirochetes of the B31A3, csrABb mutant, and csrABb complemented strains. Mice were sacrificed 3 weeks postinoculation. Ear, heart, and joint specimens were harvested for spirochete culture in BSK-II medium.

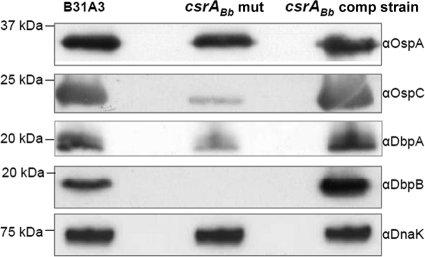

The levels of OspC, DbpB, and DbpA were significantly repressed in the csrABb mutant.

Sanjuan et al. recently reported that the overexpression of csrABb resulted in the increased levels of OspC and BBA64 (51), suggesting that CsrABb may be involved in the regulation of these virulence-associated factors. To further confirm this observation, the levels of OspA, OspC, DbpB, and DbpA were detected in the mutant. Western blotting showed that the levels of OspC, DbpB, and DbpA were significantly repressed in the mutant, whereas the level of OspA remained unchanged (Fig. 4). The complementation of the mutant successfully restored the wild-type levels of OspC, DbpB, and DbpA (Fig. 4). To determine whether these changes occur at the RNA or protein level, qRT-PCR analysis was carried out, and the results revealed that the levels of ospC and dbpA transcripts had decreased 4- to 11-fold in the mutant (Table 3), suggesting that the decrease of OspC, DbpB, and DbpA in the mutant occurs at the transcriptional level.

FIG. 4.

The levels of OspC, DbpB, and DbpA were repressed in the csrABb mutant. Three B. burgdorferi strains (B31A3, the csrABb mutant, and the csrABb complemented strain) were cultivated at 34°C/pH 7.6 and harvested at stationary phase (∼108 cells/ml). Similar amounts of whole-cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. OspA, OspC, DbpB, and DbpA were detected using specific antibodies against these proteins. DnaK was used as an internal control, as previously described (30).

TABLE 3.

qRT-PCR analysis of the csrABb mutanta

| Gene | ΔΔCT | Fold change (2ΔΔCT) |

|---|---|---|

| ospC | 2.14 | 4.40 |

| dbpA | 3.57 | 11.88 |

| dsrABb | 0.22 | 1.16 |

| ospA | 0.16 | 1.12 |

The results are expressed as normalized difference of threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) and fold change (2ΔΔCT) relative to the wild type.

The csrABb mutant has decreased RpoS.

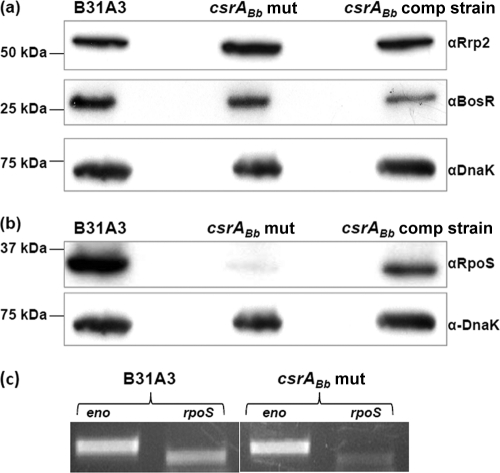

CsrA regulates target gene expression at the posttranscriptional level via influencing the stability or the translation of a given transcript. However, the study by Rajasekhar Karna et al. (44) discussed above showed that the decrease of OspC, DbpB, and DbpA in the mutant occurs at the transcriptional level, suggesting that the effect of CsrABb on the expression of ospC, dbpB, and dbpA may be indirect and that it is probably mediated by other factors. RpoS is a central regulator of B. burgdorferi and plays a very important role in the regulation of virulence factors, such as OspC, DbpB, and DbpA (13, 23). As such, we hypothesize that there may be an interplay between RpoS and CsrABb. To test this hypothesis, the level of RpoS in the csrABb mutant was detected by Western blot analysis with an antibody against RpoS. It was found that RpoS was significantly repressed in the mutant and was restored in the csrABb complemented strain (Fig. 5 b). However, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the level of rpoS mRNA was decreased (approximately 70% reduction) in the mutant (Fig. 5c), suggesting that the decrease of RpoS in the csrABb mutant occurs upstream of the RpoS pathway. The expression of rpoS is directly controlled by the alternative sigma factor RpoN, whose expression requires the activation of the response regulator Rrp2 (9, 55). In addition, recent studies showed that BosR, a homolog of the Fur regulatory protein, interfaces with the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS network (24, 38). Thus, CsrABb could indirectly influence the level of RpoS by modulating these regulators. To test this possibility, we detected BosR and Rrp2 in the mutant by Western blotting and found that the levels of these two proteins remained unchanged (Fig. 5a), indicating that CsrABb does not regulate RpoS by directly modulating either BosR or Rrp2.

FIG. 5.

The level of RpoS was repressed in the csrABb mutant. (a and b) Detection of BosR, Rrp2, and RpoS by Western blotting. Similar amounts of B31A3, csrABb mutant, and csrABb complemented strain whole-cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. DnaK was used as an internal control as described in the legend to Fig. 4. (c) qRT-PCR analysis of rpoS mRNA. Total RNA from both the wild type and the csrABb mutant was reverse transcribed to cDNA and used for the qPCR analysis of rpoS transcript. PCR samples at 30 cycles were analyzed by 1% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide staining. The enolase (eno) transcript was used as an internal control as previously described (49).

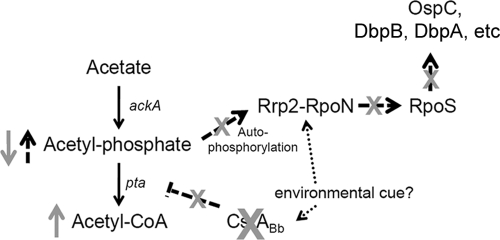

CsrABb regulates the acetate metabolism pathway.

In order to activate the RpoN-RpoS cascade, the response regulator Rrp2 first has to be phosphorylated. A recent publication by Xu et al. showed that acetyl-phosphate, an intermediate metabolite generated from the Ack-Pta (acetate kinase-acetate acetyltransferase) pathway, serves as one of the key activating molecules for the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway by phosphorylating Rrp2 (62). For instance, when the acetate metabolism pathway was interrupted via the overexpression of BB0589, a phosphate acetyltransferase (Pta) that converts acetyl-phosphate to acetyl-CoA, the activation of the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway was inhibited. To determine if CsrABb influences the activation of Rrp2 via regulation of the acetate metabolism, we analyzed the intracellular level of acetyl-CoA in both the wild type and the csrABb mutant. The results indicated that the level of acetyl-CoA was significantly increased in the mutant compared to that of the wild type (Fig. 6), implying that more acetyl-phosphate was converted to acetyl-CoA in the mutant. As such, the lesser accumulation of acetyl-phosphate in the csrABb mutant could inhibit the acetate-induced Rrp2 activation, which further leads to the repression of RpoS and the RpoS-dependent genes, such as ospC, dbpB, and dbpA.

FIG. 6.

The intracellular level of acetyl-CoA was increased in the csrABb mutant. The acetyl-CoA level in the stationary-phase culture (∼108 cells/ml) was measured using a commercial acetyl-CoA assay kit. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

CsrABb binds to the leader region of the bb0588-bb0589 transcript.

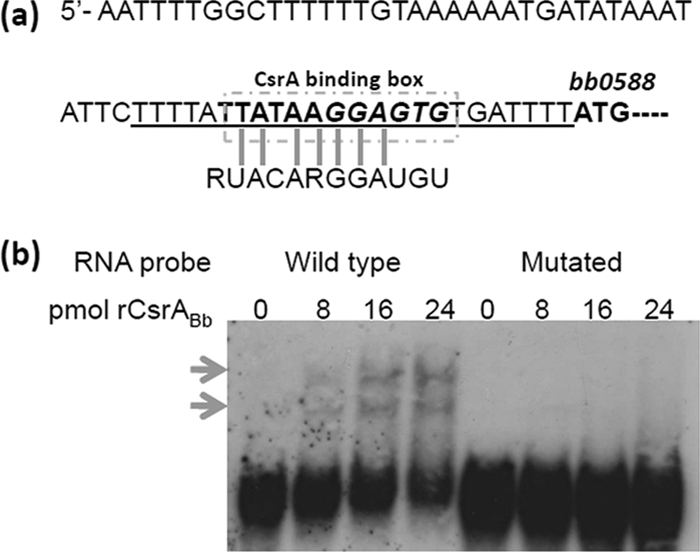

CsrA is an RNA-binding protein and affects the targeted gene via binding to a consensus sequence (RUACARGGAUGU) that is present within the targeted transcripts (14, 36). To test if the same mechanism is accountable for the interception of CsrABb on the acetate metabolism pathway, we analyzed the intergenic regions of the two genes involved in the Ack-Pta pathway (bb0622 and bb0589) and identified a potential CsrABb recognition site located upstream of the bb0588 gene (Fig. 7 a). Cotranscriptional analysis showed that both bb0588 and bb0589 are cotranscribed (data not shown) as a single transcript. To confirm the binding of CsrABb to this region, an EMSA was carried out using rCsrABb and a 23-base synthetic RNA probe encompassing the consensus sequence and the upstream region up to the start codon of bb0588 (Fig. 7a). A probe with the consensus sequence mutated from GGA to AAA was included in the assay as a negative control (Table 1). The result demonstrated that rCsrABb bound to the biotin-labeled wild-type probe and that such an interaction was abolished when the consensus site was removed (Fig. 7b). These results indicate that CsrABb specifically interacts with the leader sequence of the bb0588-bb0589 transcript. qRT-PCR analysis was also carried out to examine the transcript level of bb0589, and the result showed that there was no change at the level of transcription (data not shown). All these observations suggest that CsrABb can regulate the acetate metabolism by binding to the upstream region of bb0589 mRNA and influence its expression at the posttranscriptional level.

FIG. 7.

CsrABb binds to the 5′ UTR of the bb0588-bb0589 transcript. (a) The upstream region of the bb0588-bb0589 gene cluster. The potential CsrA binding site is boxed, a putative SD sequence is in italics, and the ATG start codon of BB0588 is bold. The vertical lines indicate the conserved residues present in the binding consensus of E. coli CsrA. The RNA sequence used for the EMSA probe is underlined. (b) EMSA. The biotin-labeled RNA probe (20 fmol) was incubated with different concentrations of rCsrABb. The experiment was carried out using the wild-type RNA probe (left) and the CsrA consensus site mutated RNA probe (right). Arrows, complexes formed between CsrB and the RNA probe.

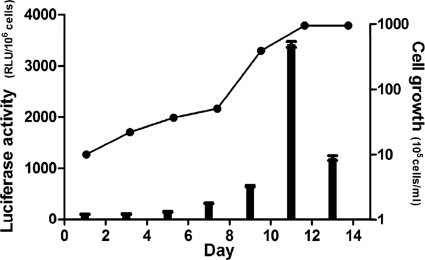

The csrABb gene is temporally regulated.

RpoS is a stress-induced sigma factor that governs the stress responses of bacteria in the stationary growth phase (21). In B. burgdorferi, the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway activation increases in response to an elevated temperature as well as an increased cell density (11, 65, 66). To test if there is any correlation between CsrABb and the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS activation, the expression level of csrABb was monitored by a previously constructed luciferase reporter vector, pJSB161 (8). The reporter was constructed by fusing PflgK, the native promoter of csrABb, to the luciferase gene (8, 17). The construct was then transformed into a high-passage B31A strain (29). The assay was carried out under the fed-tick condition (37°C/pH 6.8), based on the observation that the synthesis of CsrABb is enhanced under such a condition (51). As shown in Fig. 8, the activity of luciferase was low during the exponential growth phase but exhibited a rapid 4-fold increase as the culture entered the stationary phase, implying that the expression of csrABb is temporally regulated and that it reaches the maximum level in the stationary phase.

FIG. 8.

Luciferase reporter assay. PflgK, a native promoter of csrABb, was fused to a modified luciferase gene within the plasmid pJSB161 (8). Luciferase activity was measured using a commercial luciferase assay kit and a Veritas microplate luminometer (Promega). The data are expressed as relative luciferase units per 106 cells (RLU/106 cells).

DISCUSSION

The role of the small RNA-binding regulatory protein CsrA has been well studied with the enteric bacteria in which it functions as a global regulator involved in the regulation of carbon metabolism, motility, biofilm formation, and virulence (1, 25, 27, 28, 37, 40, 48, 64). Sanjuan et al. recently reported that the overexpression of csrABb altered the motility and several virulence factors of B. burgdorferi, such as OspC and BBA64 (51). In addition, a recent study by Rajasekhar Karna et al. reported that the targeted mutagenesis of csrABb repressed the levels of several lipoproteins, such as OspC, DbpA, and BBA64, and two key regulators, RpoS and BosR (44). These results suggest that CsrABb may be an important regulator that is required for the pathogenesis of B. burgdorferi. However, all of the studies in that report were carried out with a noninfectious strain in which infectivity was restored with the minimal region of lp25, and the genetic complementation was unable to restore the infectivity of the csrABb mutant. In addition, the potential molecular mechanism involved in the regulatory role of CsrABb has not yet been investigated. The aim of this report is to investigate the pathophysiological roles of CsrABb in B. burgdorferi by addressing the following fundamental questions: (i) whether and how does CsrABb influence the virulence of B. burgdorferi, and (ii) how does CsrABb regulate the expression of virulence factors of B. burgdorferi?

To address the first question, a csrABb mutant and its complemented strain were constructed in B31A3, a low-passage virulent strain (15). The construction of these two strains allows us to elucidate the effect of CsrABb on B. burgdorferi virulence by using the animal models of Lyme disease (7). The infectivity of the csrABb mutant was tested in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice. The results showed that the mutant failed to establish an infection in the murine model, whereas the infectivity was restored in the complemented strain (Table 2). These results have clearly demonstrated that CsrABb is required for the survival of the spirochete in the mammalian hosts. B. burgdorferi is maintained through a complex enzootic life cycle involving the tick and the mammalian hosts (26, 56, 57). The adaptation to these two different hosts is very important for the life cycle of the spirochete and for the establishment of infection. We are currently investigating whether CsrABb is required for the survival of the spirochete in the tick host by using the tick infection model.

How does CsrABb influence the virulence of B. burgdorferi? Previous studies have identified several important virulence determinants, such as OspA, OspC, DbpB, DbpA, and BBK32 (19, 31, 39, 54, 60, 67). For instance, B. burgdorferi strictly requires OspC to establish an infection in mice. The absence of BBK32, a fibronectin-binding lipoprotein, or DbpB and DbpA, two decorin-binding proteins, significantly attenuates the overall virulence of B. burgdorferi. In addition, recent studies found that the change of CsrABb influenced the levels of OspC, DbpA, and BBA64 (44, 51). Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that the inactivation of csrABb may alter the levels of these virulence determinants, which in turn leads to the failure of an infection. To test this hypothesis, the levels of OspA, OspC, DbpB, and DbpA in the mutant were measured by immunoblotting. The results showed that the levels of OspC, DbpB, and DbpA were significantly repressed in the mutant and were restored in the complemented strain (Fig. 4), suggesting that CsrABb positively regulates the expression of these virulence factors. Since OspC, DbpB, and DbpA are the important virulence determinants of B. burgdorferi, the repression of these factors could influence the infectivity of the mutant. In this report, we examined only the above three virulence determinants. It is possible that the inactivation of csrABb may also have an impact on other known or unknown virulence factors. Moreover, in E. coli, CsrA functions primarily as a regulator of carbon metabolism—glycogen biosynthesis and glycolysis (48). Thus, the inactivation of csrABb may have changed the physiological status of B. burgdorferi, limiting the spirochete's ability to survive in the mammalian host. The existence of these possibilities is currently under investigation.

How does CsrABb regulate the levels of OspC, DbpB, and DbpA? As an RNA binding protein, CsrA controls gene expression at the posttranscriptional level by influencing either mRNA stability or protein translation (5, 33, 47, 48). However, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the decrease of OspC and DbpA occurred at the transcriptional level (Table 3), suggesting that CsrABb does not directly regulate the expression of ospC, dbpB, and dbpA. In addition, the level of OspA, which is not regulated by RpoS (2), remained unchanged in the csrABb mutant (Fig. 4). Moreover, RpoS is a stress-induced sigma factor that governs the stress responses of bacteria in the stationary growth phase (21, 22). Consistently, the luciferase reporter assay indicated that the level of CsrABb was highly enhanced when the cells entered the stationary phase (Fig. 8), which coincides with the expression of RpoS. As such, we initially hypothesized that CsrABb may indirectly control the levels of OspC, DbpB, and DbpA via RpoS, a central regulator of B. burgdorferi. To test this hypothesis, the level of RpoS in the mutant was detected by Western blotting, and it was found that the level of RpoS was significantly attenuated in the mutant but was restored in the complemented strain (Fig. 5b). Upon analysis at the transcript level, we found that the level of rpoS mRNA was significantly decreased in the mutant, suggesting that the repression of RpoS expression occurred at the transcriptional level (Fig. 5c), which does not fit the common regulatory mechanism of CsrA. In addition, although a putative CsrA binding consensus was identified at the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the rpoS long transcript (34), the EMSA analysis showed that CsrABb does not bind to the transcript (data not shown). Collectively, these results indicate that CsrABb does not directly regulate RpoS.

How does CsrABb control the level of RpoS? Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS forms a central regulatory network of B. burgdorferi (11, 23, 66). RpoN directly controls the expression of RpoS, and Rrp2 is an activator of the RpoN-RpoS pathway (9, 66). In addition, recent studies showed that BosR, a homolog of the Fur regulatory protein, interfaces with the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS network (24, 38). However, the immunoblot analyses showed that the levels of BosR and Rrp2 were unaffected in the mutant (Fig. 5a), indicating that CsrABb does not regulate RpoS by directly modulating either BosR or Rrp2. However, Rajasekhar Karna et al. recently reported that the inactivation of csrABb significantly repressed the level of BosR (44). The potential reason for this discrepancy could be due to the differences in growth conditions or the strains that we used. For instance, Rajasekhar Karna et al. tested the level of BosR under the fed-tick condition (pH 6.8/37°C) in the presence of 1% CO2 (microaerobic), while we prepared the samples under the regular culture condition (pH 7.6/34°C) in the presence of 3.4% CO2. A recent identification of DsrABb, encoded by a noncoding small RNA that regulates RpoS via binding to the upstream region of rpoS mRNA (34), prompted us to examine whether DsrABb is involved in the altered RpoS level in the csrABb mutant. However, qRT-PCR analysis did not find any significant changes at the level of DsrABb (Table 3), suggesting that the influence of CsrABb on RpoS is not due to the change of DsrABb. In E. coli, CsrA interacts with CsrB and CsrC, which are encoded by two small noncoding RNAs (20, 33, 48). However, genome-mining analyses did not identify any homologues of these two RNAs in the genome of B. burgdorferi.

The activation of the RpoN-RpoS pathway requires the phosphorylation of Rrp2. A recent publication by Xu et al. showed that acetyl-phosphate from the Ack-Pta acetate metabolism pathway acts as an activating agent for the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway by phosphorylating Rrp2 (62). Since CsrA can activate the acetate metabolism in E. coli (61), we hypothesized that CsrABb may interface with the activation of the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway by regulating the Ack-Pta pathway. To test this hypothesis, we examined the intracellular level of acetyl-CoA in both the wild type and the csrABb mutant, and the results showed that the csrABb mutant has a consistently higher level of intracellular acetyl-CoA than the wild type (Fig. 6). In the report by Xu et al., when Pta (BB0589) is overexpressed in the wild type to reduce the level of acetyl-phosphate in the cell (and thus a higher level of acetyl-CoA), the temperature- and cell density-induced activation of RpoS and OspC was significantly inhibited (62). Our observation is consistent with their report in which a higher level of acetyl-CoA in the mutant inhibited the activation of Rrp2, which results in the repression of RpoS expression as well as the RpoS-dependent genes, such as ospC, dbpB, and dbpA.

CsrA is an RNA binding protein, which can recognize a consensus sequence present in a particular transcript, and its binding can lead to either the activation or the repression of gene expression (14, 36). We hypothesized that the same mechanism may be adopted by CsrABb. Upon analysis of the upstream region of bb0589, we identified a putative CsrA-binding consensus sequence located upstream of the gene bb0588 (Fig. 7a). To determine if CsrABb binds to this consensus sequence, we synthesized an RNA probe encompassing the consensus region up to the ATG start codon of bb0588 and a mutated RNA probe with the consensus sequence altered from GGA to AAA (Table 1). The EMSA result confirmed that CsrABb binds to the probe and that this interaction is specific, as the mutation of the consensus site abolished such interaction (Fig. 7b). Follow-up qRT-PCR analysis showed that the level of bb0589 mRNA remained unchanged in the mutant (data not shown), suggesting that CsrABb regulates the bb0589 transcript at the posttranscriptional level.

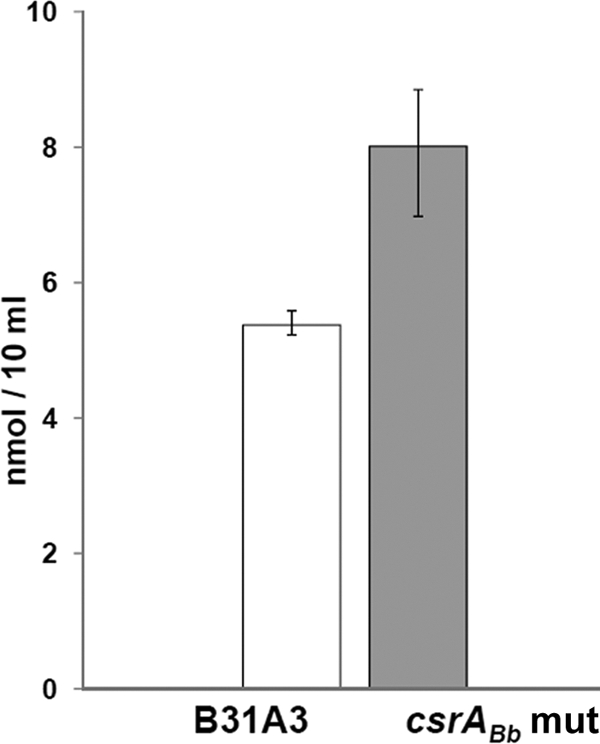

Previous studies have shown that the RpoS expression level increases in response to changes in temperature, pH, and cell entry into the stationary phase (12, 23, 34, 65). Consistently, the luciferase reporter assay showed that the level of CsrABb was highly enhanced when the cell entered the stationary phase (Fig. 8), which coincides with the activation of the RpoN-RpoS pathway. Based on these observations, we propose a working model to explain how CsrABb regulates the expression of ospC, dbpB, and dbpA via the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS network (Fig. 9). During the early growth phase, the low level of CsrABb allows the expression of Pta for the physiological metabolism of acetate through the Ack-Pta pathway. As B. burgdorferi enters the stationary phase, CsrABb expression increases and acts as a repressor to turn off the expression of Pta, which blocks the conversion of acetyl-phosphate to acetyl-CoA and consequently increases the intracellular level of acetyl-phosphate. The accumulation of acetyl-phosphate facilitates the autophosphorylation of Rrp2, which activates the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway as well as the downstream RpoS-dependent genes, such as ospC, dbpB, and dbpA. In the absence of CsrABb, the level of Pta is dysregulated during stationary phase and leads to excess conversion of intracellular acetyl-phosphate to acetyl-CoA in the mutant. A low intracellular acetyl-phosphate level prevents the autophosphorylation of Rrp2 and the activation of the RpoN-RpoS pathway, which results in the inhibition of RpoS and the expression of the RpoS-dependent genes. Schwan reported that the OspC level is rapidly upregulated following tick feeding (52), suggesting that RpoS expression can be triggered by certain environmental factors at the early growth stage. Thus, it is possible that certain environmental cues or host factors can act as a stimulant to activate the expression of CsrABb during the early stage, which in turn activates the acetate-induced activation of the Rrp2 pathway. The studies carried out in this report are only the first step to elucidate the role of CsrABb in B. burgdorferi, and many questions, including the following, still remain unveiled. How is CsrABb regulated? Do any environmental factors trigger the expression of CsrABb? Is CsrABb involved in the regulation of other virulence factors, motility, and carbon metabolism? Answering these questions will give us an overall picture about the role of CsrABb in B. burgdorferi.

FIG. 9.

Model for CsrABb regulation of the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway activation. We propose that CsrABb regulates the activation of the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway via the modulation of the level of Pta (BB0589). During the stationary phase, CsrABb reaches the maximum level and acts as a repressor to turn off the expression of Pta, which results in less conversion of acetyl-phosphate to acetyl-CoA and an increase in the intracellular level of acetyl-phosphate. An increased intracellular level of acetyl-phosphate leads to the autophosphorylation of Rrp2, which in turn activates the RpoN-RpoS cascade as well as the downstream RpoS-dependent genes. In the absence of CsrABb, the level of Pta is dysregulated and results in an enhanced conversion of acetyl-phosphate to acetyl-CoA. A low intracellular level of acetyl-phosphate prevents the autophosphorylation of Rrp2 and the activation of its downstream regulatory pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Skare, S. Samuels, F. T. Liang, and X. F. Yang for providing the antibodies and the shuttle vectors, J. Blevins for providing the luciferase reporter constructs, and N. Charon and T. Romeo for thoughtful discussion.

This research was supported by Public Service (AI073354 and AI078958) and American Heart Association grants to C. Li.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altier, C., M. Suyemoto, and S. D. Lawhon. 2000. Regulation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium invasion genes by csrA. Infect. Immun. 68:6790-6797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alverson, J., S. F. Bundle, C. D. Sohaskey, M. C. Lybecker, and D. S. Samuels. 2003. Transcriptional regulation of the ospAB and ospC promoters from Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1665-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babitzke, P., C. S. Baker, and T. Romeo. 2009. Regulation of translation initiation by RNA binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63:27-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babitzke, P., and T. Romeo. 2007. CsrB sRNA family: sequestration of RNA-binding regulatory proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:156-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker, C. S., I. Morozov, K. Suzuki, T. Romeo, and P. Babitzke. 2002. CsrA regulates glycogen biosynthesis by preventing translation of glgC in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1599-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakker, R. G., C. Li, M. R. Miller, C. Cunningham, and N. W. Charon. 2007. Identification of specific chemoattractants and genetic complementation of a Borrelia burgdorferi chemotaxis mutant: flow cytometry-based capillary tube chemotaxis assay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1180-1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barthold, S. W. 1995. Animal models for Lyme disease. Lab. Invest. 72:127-130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blevins, J. S., A. T. Revel, A. H. Smith, G. N. Bachlani, and M. V. Norgard. 2007. Adaptation of a luciferase gene reporter and lac expression system to Borrelia burgdorferi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1501-1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blevins, J. S., et al. 2009. Rrp2, a sigma54-dependent transcriptional activator of Borrelia burgdorferi, activates rpoS in an enhancer-independent manner. J. Bacteriol. 191:2902-2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks, C. S., P. S. Hefty, S. E. Jolliff, and D. R. Akins. 2003. Global analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi genes regulated by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect. Immun. 71:3371-3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burtnick, M. N., et al. 2007. Insights into the complex regulation of rpoS in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 65:277-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caimano, M. J., C. H. Eggers, K. R. Hazlett, and J. D. Radolf. 2004. RpoS is not central to the general stress response in Borrelia burgdorferi but does control expression of one or more essential virulence determinants. Infect. Immun. 72:6433-6445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caimano, M. J., et al. 2007. Analysis of the RpoS regulon in Borrelia burgdorferi in response to mammalian host signals provides insight into RpoS function during the enzootic cycle. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1193-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubey, A. K., C. S. Baker, T. Romeo, and P. Babitzke. 2005. RNA sequence and secondary structure participate in high-affinity CsrA-RNA interaction. RNA 11:1579-1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elias, A. F., et al. 2002. Clonal polymorphism of Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 MI: implications for mutagenesis in an infectious strain background. Infect. Immun. 70:2139-2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher, M. A., et al. 2005. Borrelia burgdorferi sigma54 is required for mammalian infection and vector transmission but not for tick colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:5162-5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ge, Y., I. G. Old, I. S. Girons, and N. W. Charon. 1997. The flgK motility operon of Borrelia burgdorferi is initiated by a sigma70-like promoter. Microbiology 143(5):1681-1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimm, D., A. F. Elias, K. Tilly, and P. A. Rosa. 2003. Plasmid stability during in vitro propagation of Borrelia burgdorferi assessed at a clonal level. Infect. Immun. 71:3138-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grimm, D., et al. 2004. Outer-surface protein C of the Lyme disease spirochete: a protein induced in ticks for infection of mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:3142-3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gudapaty, S., K. Suzuki, X. Wang, P. Babitzke, and T. Romeo. 2001. Regulatory interactions of Csr components: the RNA binding protein CsrA activates csrB transcription in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:6017-6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2002. Recent insights into the general stress response regulatory network in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:341-346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2002. Stationary phase gene regulation: what makes an Escherichia coli promoter sigmaS-selective? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:591-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hübner, A., et al. 2001. Expression of Borrelia burgdorferi OspC and DbpA is controlled by a RpoN-RpoS regulatory pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:12724-12729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyde, J. A., D. K. Shaw, I. R. Smith, J. P. Trzeciakowski, and J. T. Skare. 2009. The BosR regulatory protein of Borrelia burgdorferi interfaces with the RpoS regulatory pathway and modulates both the oxidative stress response and pathogenic properties of the Lyme disease spirochete. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1344-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson, D. W., et al. 2002. Biofilm formation and dispersal under the influence of the global regulator CsrA of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:290-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lane, R. S., and J. E. Loye. 1991. Lyme disease in California: interrelationship of ixodid ticks (Acari), rodents, and Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Med. Entomol. 28:719-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawhon, S. D., et al. 2003. Global regulation by CsrA in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1633-1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenz, D. H., M. B. Miller, J. Zhu, R. V. Kulkarni, and B. L. Bassler. 2005. CsrA and three redundant small RNAs regulate quorum sensing in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 58:1186-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, C., et al. 2002. Asymmetrical flagellar rotation in Borrelia burgdorferi nonchemotactic mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:6169-6174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, C., H. Xu, K. Zhang, and F. T. Liang. 2010. Inactivation of a putative flagellar motor switch protein FliG1 prevents Borrelia burgdorferi from swimming in highly viscous media and blocks its infectivity. Mol. Microbiol. 75:1563-1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, X., X. Liu, D. S. Beck, F. S. Kantor, and E. Fikrig. 2006. Borrelia burgdorferi lacking BBK32, a fibronectin-binding protein, retains full pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 74:3305-3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, M. Y., et al. 1997. The RNA molecule CsrB binds to the global regulatory protein CsrA and antagonizes its activity in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 272:17502-17510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, M. Y., and T. Romeo. 1997. The global regulator Cs6rA of Escherichia coli is a specific mRNA-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 179:4639-4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lybecker, M. C., and D. S. Samuels. 2007. Temperature-induced regulation of RpoS by a small RNA in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1075-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDowell, J. V., S. Y. Sung, M. Labandeira-Rey, J. T. Skare, and R. T. Marconi. 2001. Analysis of mechanisms associated with loss of infectivity of clonal populations of Borrelia burgdorferi B31MI. Infect. Immun. 69:3670-3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mercante, J., A. N. Edwards, A. K. Dubey, P. Babitzke, and T. Romeo. 2009. Molecular geometry of CsrA (RsmA) binding to RNA and its implications for regulated expression. J. Mol. Biol. 392:511-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulcahy, H., et al. 2008. Pseudomonas aeruginosa RsmA plays an important role during murine infection by influencing colonization, virulence, persistence, and pulmonary inflammation. Infect. Immun. 76:632-638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ouyang, Z., et al. 2009. BosR (BB0647) governs virulence expression in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1331-1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pal, U., et al. 2004. OspC facilitates Borrelia burgdorferi invasion of Ixodes scapularis salivary glands. J. Clin. Invest. 113:220-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pessi, G., et al. 2001. The global posttranscriptional regulator RsmA modulates production of virulence determinants and N-acylhomoserine lactones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 183:6676-6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prüss, B. M., and A. J. Wolfe. 1994. Regulation of acetyl phosphate synthesis and degradation, and the control of flagellar expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 12:973-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Purser, J. E., et al. 2003. A plasmid-encoded nicotinamidase (PncA) is essential for infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in a mammalian host. Mol. Microbiol. 48:753-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Purser, J. E., and S. J. Norris. 2000. Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:13865-13870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajasekhar Karna, S. L., et al. 2011. CsrABb modulates levels of lipoproteins and key regulators of gene expression (RpoS and BosR) critical for pathogenic mechanisms of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 79:732-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Revel, A. T., A. M. Talaat, and M. V. Norgard. 2002. DNA microarray analysis of differential gene expression in Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:1562-1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rogers, E. A., et al. 2009. Rrp1, a cyclic-di-GMP-producing response regulator, is an important regulator of Borrelia burgdorferi core cellular functions. Mol. Microbiol. 71:1551-1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Romeo, T. 1996. Post-transcriptional regulation of bacterial carbohydrate metabolism: evidence that the gene product CsrA is a global mRNA decay factor. Res. Microbiol. 147:505-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romeo, T. 1998. Global regulation by the small RNA-binding protein CsrA and the non-coding RNA molecule CsrB. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1321-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sal, M. S., et al. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi uniquely regulates its motility genes and has an intricate flagellar hook-basal body structure. J. Bacteriol. 190:1912-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samuels, D. S. 1995. Electrotransformation of the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Methods Mol. Biol. 47:253-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanjuan, E., M. D. Esteve-Gassent, M. Maruskova, and J. Seshu. 2009. Overexpression of CsrA (BB0184) alters the morphology and antigen profiles of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 77:5149-5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwan, T. G. 2003. Temporal regulation of outer surface proteins of the Lyme-disease spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:108-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwan, T. G., J. Piesman, W. T. Golde, M. C. Dolan, and P. A. Rosa. 1995. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:2909-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shi, Y., Q. Xu, K. McShan, and F. T. Liang. 2008. Both decorin-binding proteins A and B are critical for the overall virulence of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 76:1239-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith, A. H., J. S. Blevins, G. N. Bachlani, X. F. Yang, and M. V. Norgard. 2007. Evidence that RpoS (sigmaS) in Borrelia burgdorferi is controlled directly by RpoN (sigma54/sigmaN). J. Bacteriol. 189:2139-2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spielman, A. 1994. The emergence of Lyme disease and human babesiosis in a changing environment. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 740:146-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steere, A. C., J. Coburn, and L. Glickstein. 2004. The emergence of Lyme disease. J. Clin. Invest. 113:1093-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suzuki, K., P. Babitzke, S. R. Kushner, and T. Romeo. 2006. Identification of a novel regulatory protein (CsrD) that targets the global regulatory RNAs CsrB and CsrC for degradation by RNase E. Genes Dev. 20:2605-2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tilly, K., A. Bestor, D. P. Dulebohn, and P. A. Rosa. 2009. OspC-independent infection and dissemination by host-adapted Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 77:2672-2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weening, E. H., et al. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi lacking DbpBA exhibits an early survival defect during experimental infection. Infect. Immun. 76:5694-5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wei, B., S. Shin, D. LaPorte, A. J. Wolfe, and T. Romeo. 2000. Global regulatory mutations in csrA and rpoS cause severe central carbon stress in Escherichia coli in the presence of acetate. J. Bacteriol. 182:1632-1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu, H., et al. 2010. Role of acetyl-phosphate in activation of the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS pathway in Borrelia burgdorferi. PLoS Pathog. 6(9):e1001104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu, Q., K. McShan, and F. T. Liang. 2008. Essential protective role attributed to the surface lipoproteins of Borrelia burgdorferi against innate defences. Mol. Microbiol. 69:15-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yakhnin, H., et al. 2007. CsrA of Bacillus subtilis regulates translation initiation of the gene encoding the flagellin protein (hag) by blocking ribosome binding. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1605-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang, X., et al. 2000. Interdependence of environmental factors influencing reciprocal patterns of gene expression in virulent Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1470-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang, X. F., S. M. Alani, and M. V. Norgard. 2003. The response regulator Rrp2 is essential for the expression of major membrane lipoproteins in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:11001-11006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang, X. F., U. Pal, S. M. Alani, E. Fikrig, and M. V. Norgard. 2004. Essential role for OspA/B in the life cycle of the Lyme disease spirochete. J. Exp. Med. 199:641-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]