Abstract

Treponema pallidum, the causative agent of syphilis, is a highly invasive pathogenic spirochete capable of attaching to host cells, invading the tissue barrier, and undergoing rapid widespread dissemination via the circulatory system. The T. pallidum adhesin Tp0751 was previously shown to bind laminin, the most abundant component of the basement membrane, suggesting a role for this adhesin in host tissue colonization and bacterial dissemination. We hypothesized that similar to that of other invasive pathogens, the interaction of T. pallidum with host coagulation proteins, such as fibrinogen, may also be crucial for dissemination via the circulatory system. To test this prediction, we used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methodology to demonstrate specific binding of soluble recombinant Tp0751 to human fibrinogen. Click-chemistry-based palmitoylation profiling of heterologously expressed Tp0751 confirmed the presence of a lipid attachment site within this adhesin. Analysis of the Tp0751 primary sequence revealed the presence of a C-terminal putative HEXXH metalloprotease motif, and in vitro degradation assays confirmed that recombinant Tp0751 purified from both insect and Escherichia coli expression systems degrades human fibrinogen and laminin. The proteolytic activity of Tp0751 was abolished by the presence of the metalloprotease inhibitor 1,10-phenanthroline. Further, inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry showed that Tp0751 binds zinc and calcium. Collectively, these results indicate that Tp0751 is a zinc-dependent, membrane-associated protease that exhibits metalloprotease-like characteristics. However, site-directed mutagenesis of the HEXXH motif to HQXXH did not abolish the proteolytic activity of Tp0751, indicating that further mutagenesis studies are required to elucidate the critical active site residues associated with this protein. This study represents the first published description of a T. pallidum protease capable of degrading host components and thus provides novel insight into the mechanism of T. pallidum dissemination.

The spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum is the causative agent of syphilis, a chronic multistage sexually transmitted disease. New cases of syphilis now affect more than 15 million people each year, resulting in a 20% increase in global syphilis cases over the past 3 years. The majority of these infections occur within developing nations (26), although over the course of the past decade rapidly increasing annual syphilis infection rates have been observed in North America (38), Europe (61), and Australia (37). Congenital syphilis remains a major global pediatric health concern, with 50% of infected fetuses dying in utero or shortly after birth. Also, it is now well established that T. pallidum infection results in an increased risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV (53).

Treponema pallidum is a highly invasive pathogen capable of attaching to host cells, invading the tissue barrier and undergoing rapid dissemination via the circulatory system. In humans, the primary T. pallidum localized infection manifests itself as a chancre; however, the bacteria disseminate rapidly, resulting in widespread infection (40). In vitro, the bacteria are capable of penetrating intercellular junctions of endothelial cell monolayers (71, 72) and mouse abdominal wall tissue barriers (62). In rabbits, T. pallidum is capable of entering the circulatory system minutes after intratesticular inoculation (17, 60). The ability to disseminate so widely and rapidly is likely to be a crucial mechanism of pathogenesis for this bacterium; however, investigations focusing on the identification of proteins involved in T. pallidum pathogenesis have been hindered due to the fact that the microbe is an obligate human pathogen that cannot be continuously cultured in vitro. As a consequence, T. pallidum virulence factors have yet to be identified. Complete genome sequencing of the 1.14-Mbp Nichols strain identified 17% of the open reading frames (ORFs) as coding for hypothetical proteins, with an additional 28% of ORFs categorized as those of unknown function (24). These findings, in conjunction with an absence of identified potential classical bacterial virulence factors from the remaining 55% of annotated ORFs, further underscore the current lack of understanding regarding proteins critical for the virulence and pathogenesis of this important enigmatic human pathogen and the difficulty in identifying suitable targets for vaccine design.

Adhesin-mediated microbial adherence is a key mechanism in the colonization, establishment, and dissemination of pathogenic bacteria (52, 55). Although it is now 13 years since the publication of the Nichols strain complete genome sequence (24) and over 30 years since initial binding studies demonstrated that T. pallidum is capable of adhering to mammalian cells (3, 21, 30) and components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) (23, 70), data regarding the molecular basis of these important pathogenic interactions have only recently begun to emerge. Previously, our laboratory identified the T. pallidum adhesin Tp0751 and demonstrated that this adhesin binds specifically to a variety of laminin isoforms, which are abundant glycoprotein components of the basement membrane that underlie endothelial cell layers, in a dose-dependent manner (8, 9). Furthermore, the presence of Tp0751-specific antibodies in serum from both natural and experimental T. pallidum infections was also demonstrated (8), indicating that the protein is expressed during the course of infection. Heterologous expression of Tp0751 on the surface of the culturable nonadherent spirochete Treponema phagedenis was shown to confer upon the bacterium the ability to bind laminin, a specific interaction which was inhibited by antibodies generated against recombinant T. pallidum Tp0751 (11). Although this interaction was hypothesized to be central to the infection process (8, 9), the exact role of Tp0751 in T. pallidum tissue invasion and rapid widespread dissemination remained to be determined.

Expression of proteases in pathogenic bacteria is a mechanism commonly employed for the purpose of host component and tissue proteolysis (50, 68). This process has been linked to the virulence of many pathogenic bacteria, including Vibrio cholerae (27), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (48), and Legionella pneumophila (13, 51), by observations that it promotes bacterial invasion and dissemination of infection via the degradation of structural tissue components and plasma proteins. Host-interacting proteases have yet to be identified within T. pallidum at either an experimental or a bioinformatic level, although the highly invasive nature of this bacterium suggests their existence.

Fibrinogen (Fg) is an abundant protein synthesized primarily in the liver but also present in the blood at approximately 2 mg/ml. It is considered a positive acute-phase reactant protein since plasma concentrations increase in response to inflammation. It is a 340-kDa glycoprotein dimer comprised of three pairs of nonidentical polypeptide chains, namely, α (∼67 kDa), β (∼55 kDa), and γ chains (∼48 kDa) (32). This multifunctional protein is a key component of the host coagulation cascade and is also found in the ECM at damaged tissue sites (64). The primary role of fibrinogen is that of the key structural clotting protein in blood plasma; as such, fibrinogen is converted to fibrin by the action of thrombin. This function is believed to be important for bacterial containment; however, many pathogenic bacteria have evolved mechanisms to overcome this host defense strategy.

In the current study we further investigate the binding capability of the T. pallidum adhesin Tp0751 by expressing the full-length mature protein in a soluble form and by demonstrating the capacity of this protein to bind to human fibrinogen. We also show that Tp0751 is palmitoylated when expressed in the spirochete Treponema phagedenis, possesses zinc-dependent protease activity, and is capable of degrading human fibrinogen and laminin. We therefore propose to assign Tp0751 the name “pallilysin,” a name that reflects a combination of the nomenclature used for several bacterial proteases involved in host component degradation and the Treponema denticola protease dentilisin (36). To our knowledge, this represents the first published report of a T. pallidum protein capable of degrading host molecules and suggests a novel proteolytic mechanism for tissue damage, destruction, and dissemination of T. pallidum during the course of infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

T. pallidum subsp. pallidum (Nichols strain) was propagated in New Zealand White rabbits as described elsewhere (45). All animal studies were approved by the University of Victoria Institutional Review Board and conducted in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC) guidelines.

Host proteins.

Plasminogen-depleted human fibrinogen (Calbiochem) was purchased from VWR International (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Laminin isolated from an Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm murine sarcoma was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (Oakville, Ontario, Canada).

Construct cloning and site-directed mutagenesis.

For Escherichia coli recombinant protein expression, Tp0751 (GenBank accession number AAC65720) DNA fragments encoding amino acid residues C24 to P237, F25 to P237, and S78 to P237 were PCR amplified from T. pallidum subsp. pallidum (Nichols strain) genomic DNA using the primers listed in Table 1. Each amplicon was cloned into the T7 promoter destination expression vector pDEST-17 (which had been modified to incorporate an N-terminal thrombin site for histidine tag removal), according to the manufacturer's instructions (Gateway Technology, Invitrogen). The pDEST-17 expression vector allows for the generation of N-terminally fused hexahistidine-tagged recombinant proteins. For insect recombinant protein expression, Tp0751 DNA fragments encoding amino acid residues C24 to P237 were PCR amplified using the primers listed in Table 1. The amplicon was then cloned into the NotI/NcoI sites of a pAcGP67B baculovirus transfer vector (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) modified to incorporate a C-terminal hexahistidine tag and thrombin cleavage site. This vector also included the GP67 secretion sequence which allows for the export of recombinant Tp0751 protein into the insect culture medium. For Tp0453 (GenBank accession number AAC65443) expression, a DNA fragment encoding amino acid residues A32 to S287 was PCR amplified from T. pallidum subsp. pallidum (Nichols strain) genomic DNA using the primers listed in Table 1. The amplicon was cloned into the NdeI/XhoI sites of the pET28a expression vector (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The negative control, katE (LIC12032) (GenBank accession number AAS70607), was cloned as previously described (20). For site-directed mutagenesis, the pDEST-17 Tp0751_S78-P237 construct described above was subjected to replacement of E199 with Q199 using the primers listed in Table 1 and the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene; purchased from VWR International), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sequence and reading frames of all the expression constructs were verified as correct by DNA sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Primers used to amplify DNA for recombinant protein expression

| ORF (type)b | Primer orientation | Sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| Tp0751_C24-P237 (E) | Sense | 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGCTTTCAGCACGGTCAC |

| Antisense | 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTTTCAGGGCGAAGGAGCACTAG | |

| Tp0751_C24-P237 (I) | Sense | 5′-CTACTACCATGGCTTGCTTTCAGCACGGTCACG |

| Antisense | 5′-CTACTAGCGGCCGCGGGCGAAGGAGCACTAGC | |

| Tp0751_F25-P237 (E) | Sense | 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTTCAGCACGGTCACG |

| Antisense | 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTTTCAGGGCGAAGGAGCACTAG | |

| Tp0751_S78-P237 (E) | Sense | 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCACATGGAAACGCCCCGCC |

| Antisense | 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTTTCAGGGCGAAGGAGCACTAG | |

| Tp0751_S78-P237 (E) (M) | Sense | 5′-GGTAACATTTGAATCCCACCAGGTGATACACGTAAGGG |

| Antisense | 5′-CCCTTACGTGTATCACCTGGTGGGATTCAAATCTTACC | |

| Tp0453 (E) | Sense | 5′-CTAGACCATATGGCATCAGTAGATCCGTTGG |

| Antisense | 5′-GTCAGCTCGAGTCACGAACTTCCCTTTTTGGAG | |

| LIC12032/KatE (E) | Sense | 5′-CTAGACCATATGATGAGTAGAAAAACCCTTACTAC |

| Antisense | 5′-GTCAGAAGCTTTTAAACTCGACTCAGAGCAAG |

Restriction sites are highlighted in bold. Base changes resulting in the site-directed mutation are underlined.

E, E. coli expressed; I, insect expressed; M, mutated.

Recombinant protein expression and purification.

For E. coli recombinant protein expression, the pDEST-17 expression constructs of tp0751 were transformed into the E. coli expression strain BL21-AI (Invitrogen). Transformants were cultured in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37°C until the A600 reached 1.7 to 2.0. Bacterial cultures were induced with 0.2% l-arabinose for 16 h at 16°C, harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 1% glycerol), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. After thawing, cell pellets were lysed by adding CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate} buffer to a final concentration of 5 mg/ml (Sigma) and subjected to mild sonication and centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The tp0453 construct was transformed into the E. coli expression strain BL21 Star(DE3) (Invitrogen), and transformants were cultured in LB medium broth containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin at 37°C until the A600 reached 1.0. Cultures were induced with 0.4 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 16 h at 16°C. Fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) purification of soluble histidine-tagged recombinant proteins was performed using immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC). Briefly, proteins were injected onto 1-ml HisTrap FF affinity columns (GE Healthcare, Baie D'Urfe, Quebec City, Canada) prepacked with precharged nickel Sepharose 6 fast flow resin using an AKTA Prime Plus FPLC system (GE Healthcare). The columns were washed with cold buffer (20 mM imidazole, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 500 mM NaCl, 1% glycerol), and the bound proteins were eluted with a gradient of cold elution buffer (0 to 500 mM imidazole, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 500 mM NaCl, 1% glycerol). Fractions were monitored measuring the optical density at 280 nm (OD280) using the AKTA prime plus spectrophotometer. The purity of eluted proteins was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie brilliant blue staining. LIC12032 (KatE) was expressed as previously described (20) and purified as described above. Histidine tag removal from recombinant Tp0751 was accomplished by cleavage with thrombin (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fractions containing the recombinant proteins (estimated purity of >95%) were pooled, concentrated using 10-kDa-molecular-mass-cutoff Millipore Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter units (Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada), and loaded onto a preparative gel filtration column (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75; GE Healthcare) previously equilibrated in 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, and 1% glycerol. Recombinant proteins were eluted in cold elution buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, and 1% glycerol). Peak protein fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, concentrated as described above, quantitated by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm and by the Thermo Scientific BCA protein assay kit (Fisher Scientific), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Insoluble recombinant histidine-tagged Tp0751 LBR protein was expressed and purified as previously described (8). Insect recombinant protein expression was performed as previously described (16).

Fibrinogen-binding adherence assays.

To test for the adherence of recombinant His-tagged proteins (Tp0751 and the negative-control Tp0453) to fibrinogen, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based assays were performed as previously described (8). The plates were read at 600 nm with a BioTek ELISA plate reader (Fisher Scientific). Statistical analyses were performed using the Student two-tailed t test.

Lipoprotein determination.

The 17-octadecynoic acid (17-ODYA) labeling and detection of palmitoylated Tp0751 protein from Treponema phagedenis transformed with the tp0751 gene from T. pallidum subsp. pallidum Nichols strain (11) were based on the method developed by Martin and Cravatt (46). Briefly, cultured cells were metabolically labeled by adding 17-ODYA (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI) to tp0751-transformed T. phagedenis cultures grown to early exponential phase (1.0 × 108 cells/ml). Treponema phagedenis cultures transformed with tp0751 were grown in the absence of 17-ODYA as a negative control. Bacteria were grown until late exponential phase (7.0 × 108 cells/ml), washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS), lysed using sonication, and separated into soluble (supernatant) and insoluble (membrane) fractions by centrifugation. The insoluble pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-1% Triton X-100, and rotated at 4°C for 1 h. Samples were desalted with NAP-5 columns (GE Healthcare) to remove excess probe and other probe-incorporated metabolites, and the protein concentration was determined by UV (280 nm) absorbance. Click chemistry was used to add the reporter group, biotin-azide, to the lysate. Briefly, 1.5 mg/ml lysate per culture was reacted with 100 μM biotin-azide (Invitrogen) for 1 h in the presence of 1 mM Tris phosphine (TCEP; Sigma), 100 μM Tris ([1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3 triazol-4-yl] methyl) amine (TBTA; Sigma) in 20% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-80% t-butanol, and 1 mM CuSO4. Precipitated protein was washed twice with cold methanol, and protein pellets were sonicated in 1.2% SDS-PBS until solubilized. Samples were boiled for 5 min, diluted in PBS, and frozen at −80°C overnight. After the samples were thawed on ice, streptavidin-agarose beads (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) were added to the samples and rotated for 90 min at room temperature. Samples were washed 1 time with 10 ml PBS-0.2% SDS, 3 times with 10 ml PBS, and 3 times with 10 ml 50 mM Tris (pH 6.8). Biotin-labeled lipoproteins bound to streptavidin beads were separated by SDS-PAGE using 12% precast Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen) and stained with GelCode blue stain (Thermo Scientific), and bands corresponding to the approximate size of Tp0751 were excised and analyzed by mass spectrometry as described below.

LC-MS/MS.

Protein bands were reduced in 10 mM dithiothreitol, alkylated in 100 mM iodoacetamide, and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion for 5 h at 37°C and lyophilization to dryness. The protein samples were rehydrated in 2% acetonitrile-0.1% formic acid, concentrated, and desalted. Samples were subjected to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis using a Waters NanoAcquity UPLC coupled to an Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA)/MDS Sciex QSTAR Pulsar I mass spectrometer. Mass spectrum analyses were acquired by collecting a 1-s time-of-flight (TOF) MS survey scan (400 to 1,600 m/z) followed by two 2.5-s product ion scans. LC-MS/MS data were searched by centroiding with Analyst QS 1.1 Mascot script 1.6 b24 (MDS Sciex, Concord, Ontario, Canada) to create the Mascot generic format file (mgf) for database searching. The mgf files were searched against the Uniprot-Swissprot 20090225 (410,518 sequences; 148,080,998 residues) “all species” or “Eubacteria species only” and “Treponema pallidum (Nichols strain)” databases with the following parameters: fixed modifications included carbamidomethyl (C), deamidation (NQ), oxidation (M), and propionamide (C); NHS-biotin was set as a variable modification; peptide mass tolerance was ±0.3 amu; fragment mass tolerance was ±0.15 amu; and enzyme specificity was set for trypsin.

In vitro substrate degradation assays.

The E. coli-expressed recombinant proteins Tp0751_C24-P237, Tp0751_S78-P237 (wild-type and mutant E199Q), and KatE (LIC12032) and the insect-expressed Tp0751_C24-P237 recombinant protein (30 μg) were mixed with 60 μg of plasminogen-free human fibrinogen or laminin in protease activation buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 25 mM CaCl2). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 0 to 24 h, and samples were removed at various time points. Samples from each time point (10 μl) were mixed with 10 μl of sample buffer and heated at 95°C for 10 min, and the three fibrinogen chains, (α, β, and γ) or three laminin chains (A, B1, and B2) were separated and analyzed for degradation by electrophoresis in 15% and 10% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gels, respectively, at a constant voltage of 200 V for 1 h. Gels were stained in Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 solution and destained in 5% (vol/vol) acetic acid, 20% (vol/vol) methanol, and 75% (vol/vol) H2O. For densitometry analysis of fibrinogen and laminin degradation, the freely available ImageJ software from the National Institutes of Health was used (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). The following parameters were used for analysis: image type was set to grayscale/inverted, background noise subtracted with rolling ball radius was set to 50, scale/unit of length was set to pixels, and measurements were set to area, mean gray value, and integrated density. Relative intensities of SDS-PAGE bands were calculated as the mean gray value at a t of 24 h/mean gray value at a t of 0 h.

Fibrinogen degradation FRET assays.

A fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based assay was developed to analyze the fibrinogenolytic activity of Tp0751. Plasminogen-free human fibrinogen was labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) as previously described (78). The FITC-labeled fibrinogen assay for measuring Tp0751 protease activity was based on the method of Twining (73). Briefly, the recombinant proteins (Tp0751_C24-P237 and the negative-control KatE) and the positive-control protease, trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI), were diluted in activation buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 25 mM CaCl2) to give a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. One hundred microliters of the protein solutions was added in triplicate to sterile Corning Costar 96-well plates (1.0 μg per well) (Fisher Scientific). Blank sample wells consisted of activation buffer in the absence of recombinant proteins. FITC-labeled fibrinogen (10 μg) was added to all sample wells, mixed gently, and incubated at 37°C in the dark for 0 to 48 h. Fluorescence was measured hourly using a standard fluorescein excitation/emission filter set at 485 nm/538 nm and a BioTek Synergy HT plate reader (Fisher Scientific). The mean blank fluorescence readings were subtracted from the mean sample fluorescence readings for each protein, and the increase in relative fluorescence units (RFU) was plotted against time. Statistical analyses were performed using Student's two-tailed t test.

Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry analysis.

Metal cofactors present in Tp0751 protein samples were analyzed at Cantest Ltd. (Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada) using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Briefly, Tp0751_S78-P237 protein and purification buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1% glycerol) were dispensed into individual 15-ml polypropylene tubes. Both samples were reacted with 200 μl of nitric acid and heated in a 95°C hot water bath for 1 h. The digested solutions were made up to a final volume of 5 ml with deionized water. The samples were analyzed by conventional ICP-MS at a dilution of ×5. The metal elements Zn, Ca, Mn, Mg, Fe, and Co were fully quantified against a certified standard using single-point calibration. Sample analysis and operation of the ICP-MS were done according to Cantest's in-house standard operating procedures.

Protease inhibition assays.

To investigate the effect of various broad-spectrum protease inhibitors on the proteolytic activity of Tp0751, recombinant proteins in protease activation buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 25 mM CaCl2) were incubated at 37°C for 1 h in the presence and absence of 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM and 10 mM 1,10-phenanthroline, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM benzamidine, or 200 μM trans-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucylamido-(4-guanidino) butane (E64) (all inhibitors purchased from Sigma). Inhibitor stock solutions were prepared immediately before use and filter sterilized using 0.2 μm syringe filters (Sarstedt Inc., Montreal, Quebec City, Canada). The proteolytic activity of the samples was analyzed using the SDS-PAGE-based in vitro substrate degradation and FRET-based degradation assays as detailed above.

RESULTS

Soluble expression of recombinant Tp0751 protein.

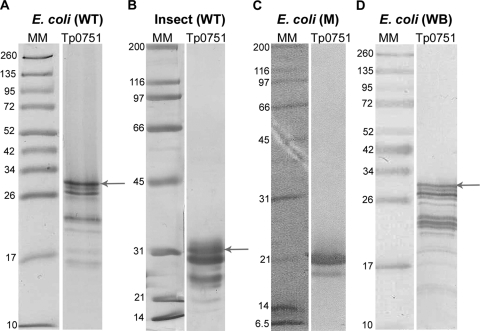

In order to investigate the potential role of the adhesin Tp0751 in T. pallidum dissemination, several Tp0751 constructs were cloned and tested for soluble protein expression (Table 2). Soluble expression was achieved only when C-terminal amino acids, in particular amino acid residues P231 to P237 (PASAPSP), were included in the construct design. Truncation of N-terminal residues M1 to R77 did not adversely affect soluble protein expression. Electrophoresis of purified Tp0751 proteins by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining (Fig. 1 A and B) revealed the presence of multiple bands, and Western blot analysis using Tp0751-specific polyclonal antibodies (Fig. 1D) similarly detected multiple immunoreactive protein bands. E. coli (Fig. 1A)- and insect (Fig. 1B)-expressed Tp0751_C24-P237 molecular masses ranged from approximately 32 kDa to approximately 15 kDa. In-gel tryptic digestion and analysis of the resulting peptides using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)-TOF MS and LC-MS/MS confirmed that all bands detected by GelCode blue staining were Tp0751 (data not shown). The MS sequence coverage data indicated that the lower-mass bands represent Tp0751 protein molecules which had been reduced in mass due to cleavage of amino acids from the protein termini (data not shown). The calculated molecular mass of His-tagged recombinant Tp0751_C24-P237 is 25.8 kDa; however, when analyzed using SDS-PAGE, the main Tp0751 protein band migrated in the gel with a mobility similar to that of a protein corresponding to approximately 32 kDa (Fig. 1). The slower-than-predicted anomalous migration of the protein may be due to the high proline content in the N terminus of the protein (8.4% from residue C24-P237 and 16.9% from residue C24-T100), as anomalous SDS-PAGE migration has been observed with other proline-rich proteins (33).

TABLE 2.

Recombinant expression of Tp0751 constructs

| Constructa | Expression vector(s) | Amino acids expressed | Estimated expression profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tp0751_R54-S185 | pDEST-17 | R54-S185 | 100% insoluble |

| Tp0751_R54-V200 | pDEST-17, pET28a, pET32 | R54-V200 | 100% insoluble |

| Tp0751_R54-G215 | pDEST-17 | R54-G215 | 100% insoluble |

| Tp0751_R54-W220 | pDEST-17 | R54-W220 | 100% insoluble |

| Tp0751_R54-T225 | pDEST-17 | R54-T225 | 95% insoluble |

| Tp0751_R54-G230 | pDEST-17 | R54-G230 | 95% insoluble |

| Tp0751_R54-P237 | pDEST-17 | R54-P237 | >40% soluble |

| Tp0751_S78-P237 | pDEST-17 | S78-P237 | >40% soluble |

| Tp0751_S78_P237 (M) | pDEST-17 | S78-P237 | >40% soluble |

| Tp0751_F25-P237 | pDEST-17 | F25-P237 | >50% soluble |

| Tp0751_C24-P237 | pDEST-17 | C24-P237 | >50% soluble |

| Tp0751_C24-P237 (I) | pAcGP67B | C24-P237 | >50% soluble |

All constructs were expressed in E. coli unless otherwise stated. M, mutated protein (E199Q); I, insect expressed.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of soluble E. coli- and insect-expressed recombinant Tp0751. Purified recombinant Tp0751_C24-P237 wild-type (WT) and Tp0751_S78-P237 E199Q mutant (M) proteins from E. coli (A and C) and insect (B) expression systems were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with GelCode blue (E. coli WT) or Coomassie brilliant blue (insect WT and E. coli M) staining solutions. (D) E. coli Tp0751_C24-P237 WT protein was analyzed via Western blot (WB) methodology using Tp0751-specific polyclonal antibodies. Numbers to the left of the lanes indicate the sizes (kDa) of the corresponding molecular mass (MM) markers. Electrophoresis of purified Tp0751_C24-P237 protein consistently revealed the presence of multiple protein bands, corresponding to peptides with molecular masses ranging from approximately 32 kDa to 15 kDa. The major Tp0751_C24-P237 protein bands (∼32 kDa) are indicated by arrows. Excision of each band from the gel, followed by MALDI-TOF and LC-MS/MS analyses, confirmed that all bands detected by GelCode blue staining were derived from Tp0751 (data not shown).

Recombinant Tp0751 binds specifically to human fibrinogen.

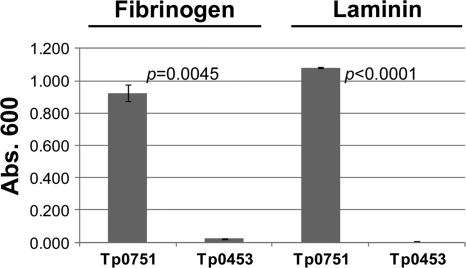

We hypothesized that, similar to the situation with other invasive bacteria, the interaction of T. pallidum with coagulation proteins is important for the rapid widespread dissemination of this pathogen via the circulatory system. Therefore, the ability of Tp0751 to bind specifically to human fibrinogen was investigated using an ELISA-based assay which compared the attachments of the adhesin and a negative-control recombinant protein, Tp0453, to immobilized plasminogen-free human fibrinogen and the positive-control host protein, laminin. Tp0453 is predicted to be located in the outer membrane of T. pallidum (31) and has previously been shown to lack significant binding to laminin (8). The soluble recombinant proteins Tp0751_C24-P237 (data not shown) and Tp0751_F25-P237 (Fig. 2) exhibited statistically significant levels of binding to both the positive-control host protein, laminin (P < 0.0001), and to plasminogen-free human fibrinogen (P = 0.0045) compared to the levels of laminin and fibrinogen binding exhibited by Tp0453. These results suggest that Tp0751 is an important factor mediating interactions with multiple host proteins in different host environments during the course of infection.

FIG. 2.

Soluble Tp0751 binds host components. The ability of soluble recombinant Tp0751 to bind plasminogen-free human fibrinogen and laminin was assessed using an ELISA-based assay. Average readings (A600) are presented with bars indicating standard error (SE). The results are representative of five independent experiments. For statistical analyses, attachment to laminin and fibrinogen by Tp0751 was compared to the attachment of Tp0453 using Student's two-tailed t test. Tp0751 exhibited a statistically significant level of binding to both the positive-control host protein, laminin (P < 0.0001), and to plasminogen-free human fibrinogen (P = 0.0045) compared to the level of laminin and fibrinogen binding exhibited by Tp0453.

Heterologously expressed Tp0751 is S-palmitoylated.

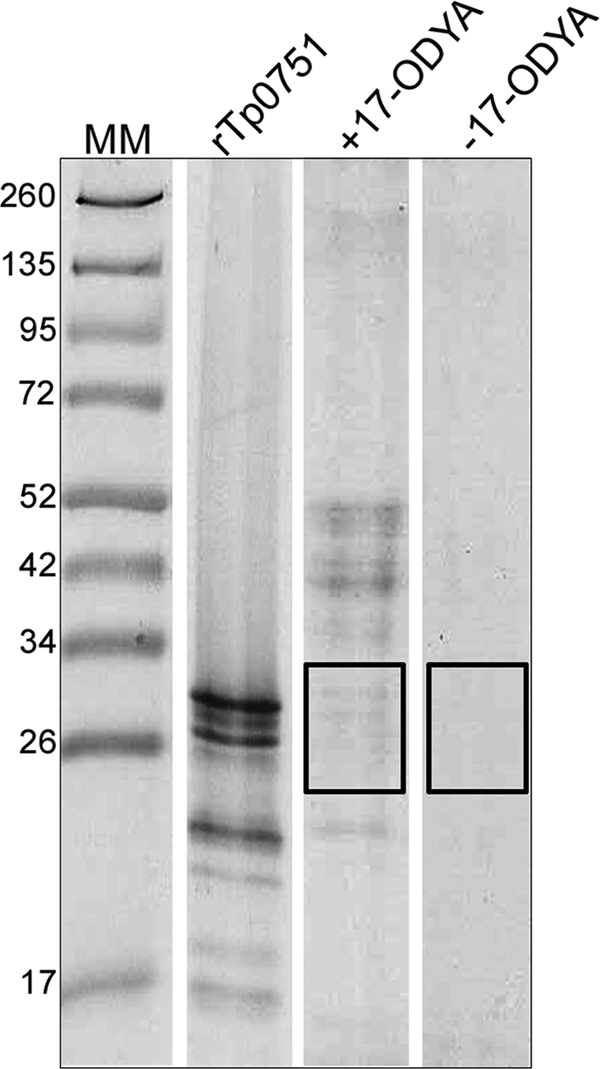

Previous in silico analysis of Tp0751 indicated the presence of a putative signal peptide II (SpII) cleavage site, suggesting that the protein may be lipidated within T. pallidum (66). In order to confirm that Tp0751 is a lipoprotein, we adapted the mammalian protein palmitoylation global profiling methodology of Martin and Cravatt (46) for use in the prokaryote T. phagedenis. For these experiments, we used Tp0751-expressing T. phagedenis (11) to enable the lipidation state of the Tp0751 adhesin to be determined in a culturable treponeme. Tp0751-expressing T. phagedenis cultures were metabolically labeled by growing cells in the presence of the palmitate analog 17-octadecynoic acid (17-ODYA), while negative-control cells were grown in the absence of the analog. The reporter group, biotin-azide, was reacted with the insoluble membrane fractions, and biotin-labeled octadecynoylated proteins resulting from the Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction (click chemistry) were purified on streptavidin beads, separated by SDS-PAGE, excised, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Following electrophoresis, approximately 15 GelCode blue-stained bands corresponding to proteins ranging from ∼20 kDa to ∼60 kDa were detected in Tp0751-transformed T. phagedenis cells cultured in the presence, but not the absence, of 17-ODYA (Fig. 3). To ensure that we could detect palmitoylated Tp0751 if present, regions of the gel within the molecular mass range of 20 kDa to 34 kDa were excised from lanes corresponding to the cultures grown in both the presence and absence of 17-ODYA and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis (Fig. 3). As shown in Table 3, Tp0751 was detected in the purified proteins from T. phagedenis grown in the presence of 17-ODYA but not in cells grown in the absence of analog. These results provide direct evidence that Tp0751 is expressed and S-palmitoylated in transformed T. phagedenis and thus provide further evidence that the protein is membrane associated in T. pallidum.

FIG. 3.

Heterologously expressed Tp0751 is lipid modified. Tp0751-expressing T. phagedenis cultures were metabolically labeled by growing cells in the presence of the palmitate analog 17-ODYA. Following click chemistry, octadecynoylated proteins were purified using streptavidin beads, separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with GelCode blue reagent. Protein bands from cultures grown in the presence (+17-ODYA) or absence (−17-ODYA; negative control) of the palmitate analog, corresponding to proteins ranging from ∼20 kDa to ∼34 kDa, were excised from the gel lanes (excised areas indicated by rectangles) and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. For comparison, the SDS-PAGE migration mobility of purified recombinant Tp0751_C24-P237 is shown (rTp0751). Numbers to the left of the lanes indicate the sizes (kDa) of the corresponding molecular mass (MM) markers.

TABLE 3.

Palmitoylated proteins identified by LC-MS/MS from 17-ODYA labeled and non-labeled tp0751-transformed T. phagedenisd

| Protein/species | 17-ODYA | Uniprot no. | Mass (Da) | No. of observed peptidesa | MASCOT scoreb | Seq. cov. (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tp0751/T. pallidum | + | 083732 Y751_ TREPA | 25,810 | 3 | 101 | 15 |

| No protein detected | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

No. of observed peptides includes all peptides that differ either by sequence, modification, or charge, with a MASCOT score equal to or greater than the significance threshold (P < 0.05).

A MASCOT score of >39 is equal to or greater than the significance threshold (P < 0.05).

Sequence coverage (Seq. cov.) is based on peptides with a unique sequence.

NA, not applicable.

Recombinant Tp0751 degrades human fibrinogen and laminin.

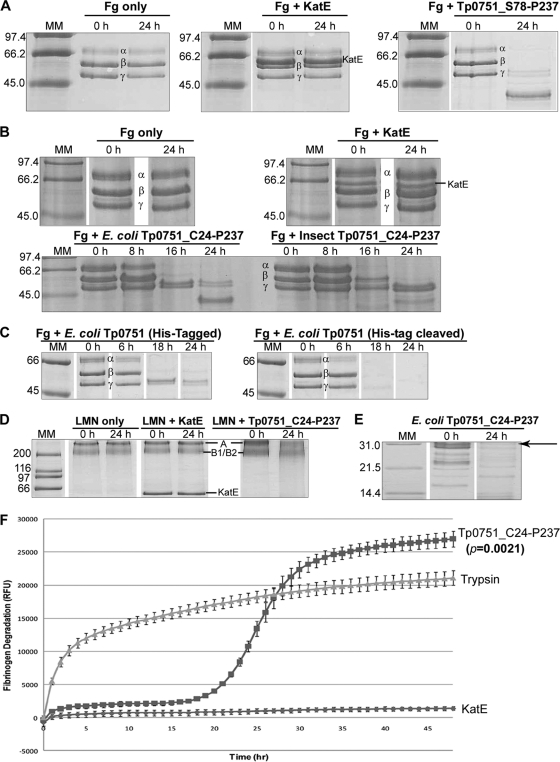

The invasive nature of T. pallidum suggests the possible existence of host-interacting proteases within this spirochete. The detection of multiple Tp0751 bands on SDS-PAGE gels, combined with the fact that the current study and previous studies within our laboratory (8, 9) have demonstrated Tp0751-ECM interactions, prompted the investigation of the primary sequence of Tp0751 for the presence of potential protease motifs. A putative conserved zinc-binding HEXXH motif (HEVIH), which is found in approximately 50% of known metalloendopeptidases, was identified in the C terminus at amino acids H198 to H202. In order to determine if Tp0751 is a protease, recombinant proteins were expressed and purified from both a baculovirus-insect cell expression system (Tp0751_C24-P237) and an E. coli expression system (Tp0751_S78-P237 and Tp0751_C24-P237). The purified recombinant proteins were incubated with either plasminogen-free human fibrinogen or laminin at 37°C. These proteins were chosen as potential substrates, as we had previously demonstrated their interaction with Tp0751 via binding assays. Samples were removed at defined time intervals, and degradation was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and subsequent staining with Coomassie blue. E. coli-expressed Tp0751_S78-P237 degraded the α, β, and γ chains of human fibrinogen by 24 h postincubation, whereas the corresponding negative controls failed to degrade any of the three fibrinogen chains over 24 h (Fig. 4 A). Time course analysis of fibrinogen degradation by the full-length mature Tp0751 protein (C24 to P237) indicated that the α and β chains were completely degraded by the E. coli-expressed protein within 8 to 16 h of incubation, with almost complete degradation of the γ chain by 16 to 24 h. Similarly, the insect-expressed protein degraded the α chain by 8 to 16 h and the β chain by 16 to 24 h (Fig. 4B). Removal of the N-terminal histidine tag from the full-length mature protein resulted in enhanced proteolysis (compared to the rate of fibrinogen degradation by the His-tagged Tp0751 protein), with complete degradation of all three fibrinogen chains by 6 to 18 h (Fig. 4C). Partial hydrolysis of laminin A, B1, and B2 chains by the full-length mature Tp0751 protein (C24 to P237) was also observed following 24 h of incubation (Fig. 4D). Densitometry analysis confirmed the laminin degradation, as the relative intensity levels (mean intensity of the protein band at t = 24 h/mean intensity of the protein band at t = 0 h) of the laminin A chain (400 kDa) and laminin B1/B2 chain (210/210 kDa) bands decreased by 62% and 23%, respectively, following 24 h of incubation with Tp0751. Densitometry (data not shown) and SDS-PAGE analyses (Fig. 4A to D) indicated that fibrinogen and laminin remained stable over the course of 24 h in the negative controls (fibrinogen/laminin incubated in buffer without a recombinant protein, and fibrinogen/laminin incubated in the presence of the recombinant Leptospira protein LIC12032/KatE). Interestingly, Tp0751 protease constructs purified from both insect cells (data not shown) and E. coli (Fig. 4E) also underwent further degradation over the course of the 24 h of incubation.

FIG. 4.

Recombinant insect-expressed and E. coli-expressed Tp0751 proteins degrade human fibrinogen and laminin and undergo self-degradation. (A) Recombinant Tp0751_S78-P237 protein purified from E. coli and (B) recombinant Tp0751_C24-P237 proteins purified from E. coli and insect cells were incubated with plasminogen-free human fibrinogen. Two negative controls were included: fibrinogen incubated in buffer without a recombinant protein (Fg only) and fibrinogen incubated in the presence of the recombinant Leptospira protein LIC12032/KatE (Fg plus KatE, negative control). (C) Following cleavage of the N-terminal histidine tag from full-length mature recombinant Tp0751, the cleaved and noncleaved proteins were incubated with fibrinogen. (D) Recombinant Tp0751_C24-P237 protein purified from E. coli was incubated with laminin (LMN). Two negative controls were included: laminin incubated in buffer without a recombinant protein (LMN only) and laminin incubated in the presence of the recombinant Leptospira protein LIC12032/KatE (LMN plus KatE, negative control). (E) Recombinant Tp0751 protease was degraded further over the course of the 24-h fibrinogen degradation assays. The major Tp0751 band (∼32 kDa) is indicated by an arrow. In all experiments, samples were removed over a 24-h time period at the indicated intervals and loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels. Degradation of the fibrinogen α, β, and γ chains and the laminin A (400-kDa), B1 (210-kDa), and B2 (200-kDa) chains and degradation of the Tp0751 protease were detected by staining with Coomassie blue. Numbers to the left of the lanes indicate the sizes (kDa) of the corresponding molecular mass (MM) markers. (F) A FRET-based assay was performed to further confirm the fibrinogenolytic activity of Tp0751. FITC-labeled plasminogen-free human fibrinogen was incubated for 48 h with either recombinant E. coli-expressed Tp0751_C24-P237, the positive-control protein trypsin, or the negative-control protein KatE. The degree of fibrinogen degradation was measured every hour by detecting the increase in relative fluorescence units (RFU) over 48 h using standard fluorescein excitation/emission filters. The increase in RFU for the three proteins is shown. Average fluorescence intensity readings from triplicate measurements are presented with bars indicating standard error (SE). The results are representative of four independent experiments. For statistical analyses, fibrinogen degradation by Tp0751 was compared to that of KatE using Student's two-tailed t test. The recombinant Tp0751_C24-P237 protein exhibited a statistically significant level of fibrinogenolysis at 20 h postincubation (P = 0.0021) and beyond, compared to the level of fibrinogen degradation exhibited by the negative-control recombinant protein KatE.

A FRET-based assay was developed to further confirm the fibrinogenolytic activity of Tp0751. FITC quenching occurs in heavily labeled FITC proteins due to the close proximity of the labels. However, upon digestion of the intact molecule by proteases, the FITC-labeled protein becomes dequenched, resulting in a measurable increase in fluorescence, indicative of proteolysis. FITC-labeled fibrinogen was incubated with E. coli-expressed Tp0751_C24-P237, and fibrinogen degradation was detected by measuring the increase in fluorescence intensities over 48 h. The relative fluorescence units (RFU) for the positive control (trypsin) increased from 13.7 RFU at 0 h postincubation to 10,150 RFU at 3 h postincubation, representing a 743-fold increase in relative fluorescence, and 48% of the total fluorescence detected at 48 h postincubation (21,091 RFU). As the graph for trypsin is approximately linear from 0 to 3 h, the maximum specific activity of trypsin, calculated as the relative increase in fluorescence units per minute, is 56.3 RFU min−1. As expected, these results indicate rapid degradation of human fibrinogen by trypsin immediately following incubation of the protease with substrate, followed by slower trypsin degradation over the next 45 h, presumably due to the loss of trypsin activity (Fig. 4F). In contrast, the RFU for Tp0751 increased slowly during the first 16 h, from zero fluorescence above background to 2,365 RFU, representing 8.8% of the total fluorescence detected at 48 h postincubation (27,005 RFU). However, the RFU for Tp0751 increased from 2,365 at 16 h postincubation to 24,821 RFU at 35 h postincubation, representing a 10.5-fold increase in relative fluorescence and 92% of the total fluorescence detected at 48 h postincubation (27,005 RFU) (Fig. 4F). The maximum specific activity of Tp0751, calculated as the relative increase in fluorescence units per minute between 22 and 28 h postincubation, is 37.1 RFU min−1. These results are in agreement with the SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 4B) and confirm that, after an initial lag period of approximately 16 h, the Tp0751 protease initiates rapid degradation of human fibrinogen to a level that exceeds the degradation potential of trypsin. As shown in Fig. 4F, recombinant Tp0751_C24-P237 exhibited a statistically significant level of fibrinogenolysis at 20 h postincubation (P = 0.0021) and beyond, compared to the level of fibrinogen degradation exhibited by the negative-control recombinant protein KatE. These results demonstrate that, in addition to the host component binding capability of Tp0751, the adhesin is also capable of degrading these host proteins.

Tp0751 protease binds zinc and is inhibited by metalloprotease inhibitors.

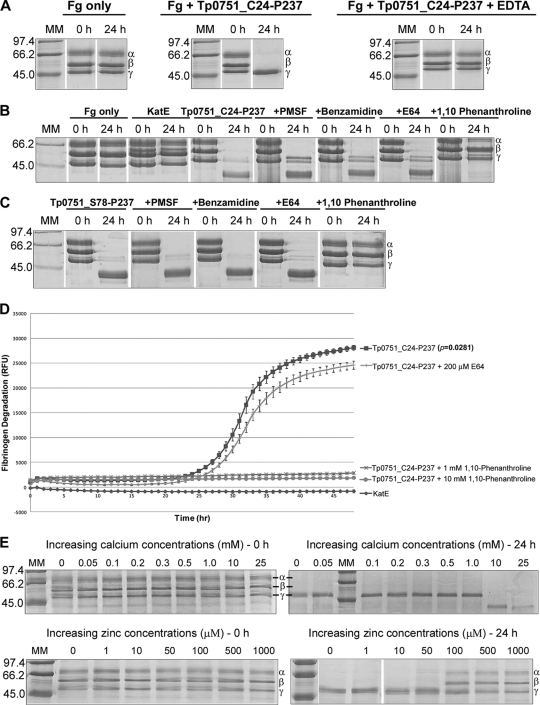

Quantitative inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) was used to investigate Tp0751 divalent metal ion binding. Analyses indicated that Tp0751 binds zinc and calcium, but not iron, magnesium, cobalt, or manganese (Table 4). In order to determine the catalytic type of the HEXXH motif-containing Tp0751 protease, various protease inhibitors were incubated with the recombinant proteins and the effect on fibrinogenolysis was analyzed using SDS-PAGE and the FRET-based assays. The metal chelator EDTA (10 mM) completely inhibited the fibrinogenolytic activity of insect-expressed Tp0751_C24-P237, as all three fibrinogen chains were found to be stable, when analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining, for up to 24 h after incubation (Fig. 5 A). Fibrinogenolysis was not inhibited when E. coli-expressed Tp0751_S78-P237 and Tp0751_C24-P237 were incubated with the serine protease inhibitor PMSF (1 mM), the serine protease inhibitor benzamidine (1 mM), or the cysteine protease inhibitor E64 (200 μM) (Fig. 5B to D). However, incubation of recombinant Tp0751 with the zinc chelator 1,10-phenanthroline (1 to 10 mM) abolished fibrinogenolytic activity (Fig. 5B to D). Fibrinogen was degraded by recombinant Tp0751 to similar extents in both the presence (1 to 100 μM) and absence of zinc. This may be explained by the fact that zinc is ubiquitous in nature and may have been incorporated into the protease active site during E. coli expression and purification, likely originating from the media and buffers used during the purification. Zinc concentrations greater than 100 μM inhibited the fibrinogenolytic activity of Tp0751 (Fig. 5E), which is consistent with the finding that high zinc concentrations inhibit metalloprotease activity due to the formation of a zinc monohydroxide complex in the active site (41) or the presence of two zinc ions in the active site (12, 34). Interestingly, when calcium was present at 0 to 1 mM concentrations, only the α and β chains were degraded, whereas increasing calcium concentrations above 10 mM enhanced proteolysis as seen by the degradation of all three fibrinogen chains (Fig. 5E). Site-directed mutagenesis studies indicated that the Tp0751 E199Q mutant degrades fibrinogen at a rate comparable to that of the wild-type protein (data not shown). Similar to that of the wild-type Tp0751 protein, the fibrinogenolytic activity of the Tp0751 E199Q mutant was inhibited by the metalloprotease inhibitor 1,10-phenanthroline, but not by serine or cysteine protease inhibitors (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

ICP-MS quantification of metal ions in purified recombinant Tp0751 protein

| Protein or metal ion | Concn in sample (nM)a | Ratio of [metal ion]:[Tp0751] |

|---|---|---|

| Tp0751 | 17.0 | |

| Zn | 7.0 | 0.4:1.0 |

| Ca | 6.8 | 0.4:1.0 |

| Fe | ND | |

| Mg | ND | |

| Co | ND | |

| Mn | ND |

ND, not detected.

FIG. 5.

Proteolytic activity of Tp0751 is abolished by metalloprotease inhibitors. (A) Insect-expressed Tp0751_C24-P237 was preincubated at 37°C with or without the metalloprotease inhibitor EDTA. E. coli-expressed Tp0751_C24-P237 (B) and Tp0751_S78-P237 (C) were preincubated at 37°C with or without the serine protease inhibitors PMSF and benzamidine, the cysteine protease inhibitor E64, and the metalloprotease inhibitor 1,10-phenanthroline. The proteins were incubated with fibrinogen for 24 h, removed at the indicated intervals, and loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels, and degradation of the fibrinogen α, β, and γ chains was detected by staining with Coomassie blue. The negative controls included fibrinogen incubated in buffer without a recombinant protein (Fg only) and fibrinogen incubated in the presence of the recombinant Leptospira protein, LIC12032/KatE (Fg + KatE). (D) E. coli-expressed Tp0751_C24-P237 was incubated with or without E64 and 1,10 phenanthroline. FITC-labeled fibrinogen was incubated for 48 h with the Tp0751_C24-P237 proteins and the negative-control protein KatE. The degree of fibrinogen degradation was measured every hour by detecting the increase in relative fluorescence units (RFU) using standard fluorescein excitation/emission filters. Average fluorescence intensity readings from triplicate measurements are presented with bars indicating standard error (SE). The results are representative of three independent experiments. For statistical analyses, fibrinogen degradation by Tp0751 in the presence (1 mM) and degradation in the absence of 1,10-phenanthroline were compared using Student's two-tailed t test. The Tp0751_C24-P237 protein not exposed to the metalloprotease inhibitor exhibited a statistically significant level of fibrinogenolysis at 25 h postincubation (P = 0.0281) and beyond, compared to the level of fibrinogen degradation exhibited by the Tp0751 protein exposed to 1,10-phenanthroline. (E) The effect of increasing calcium and zinc concentrations on fibrinogenolysis by Tp0751 was analyzed using the same SDS-PAGE assay described above. Numbers to the left of the lanes indicate the sizes (kDa) of the corresponding molecular mass (MM) markers.

DISCUSSION

It has been demonstrated that bacterial adhesins can promote antiphagocytosis (6, 57), initial establishment and maintenance of infection, and bacterial dissemination by interfering with critical sites in fibrinogen chains which are normally required for essential host defense responses to bacterial infections, including platelet and thrombin interaction sites (18, 56, 58). Although T. pallidum and T. pallidum proteins have been shown to bind to various host components, including fibronectin (10, 22), laminin, collagen I, and collagen IV (8, 9, 23), this represents the first report to identify a T. pallidum protein capable of binding specifically to human fibrinogen. Fibrinogen expression is significantly upregulated as a host defense response to infection and inflammation, with the thrombin-catalyzed conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin clots allowing for pathogen containment and localization by providing a structural protective barrier to the surrounding tissues to prevent bacterial invasion and dissemination (42). During T. pallidum infection, the bacterium could interfere with this fibrinogen function through Tp0751-mediated binding at several stages, including at the initial site of infection during chancre formation, in the bloodstream during dissemination via the circulatory system, and at sites of damaged tissue.

The ability of bacteria to degrade fibrinogen via the expression of fibrinogenolytic proteases, thereby inhibiting or preventing containment through coagulation, is an important virulence factor in various pathogenic bacterial species, promoting rapid widespread dissemination via the circulatory system (29, 35, 47, 50). The oral spirochete Treponema denticola expresses a chymotrypsin-like protease (CTLP) that is capable of degrading several host proteins, including epithelial junction-associated proteins and fibrinogen, which in turn is believed to promote bacterial colonization, hemostatic interference, and tissue invasion (2, 19, 36, 74). In the current study, recombinant Tp0751 proteins purified from both insect and E. coli expression systems degraded plasminogen-free human fibrinogen. We were also able to demonstrate that, as for other invasive pathogenic bacteria, Tp0751 is capable of degrading the abundant ECM component laminin. This attribute may also contribute to T. pallidum dissemination, given the fact that the bacterium must traverse several basement membranes during the course of infection. The current study represents the first published report to identify a T. pallidum protein that is capable of degrading human molecules.

Tp0751 possesses a potential metalloprotease zinc-binding HEXXH motif, binds zinc and calcium, and is inhibited by the zinc-chelating metalloprotease inhibitor 1,10-phenanthroline and the general metal chelator EDTA. Based upon these findings we propose to designate Tp0751 “pallilysin” to match the nomenclature used for several pathogenic bacterial proteases capable of degrading human proteins. However, the designation of the protease as a true metalloprotease cannot be made at this time, since site-directed mutagenesis performed in this study indicated that, unlike other HEXXH-containing metalloproteases (25, 43), mutation of the glutamic acid residue within the potential pallilysin metalloprotease motif did not affect the proteolytic potential. In light of this finding and the fact that 50% of known metalloproteases do not contain an HEXXH motif, it is apparent that further mutagenesis studies need to be performed to identify the pallilysin active site residues.

Candidate factors proposed to mediate the rapid, widespread dissemination of and associated tissue damage and destruction by T. pallidum have included periplasmic flagella, chemotaxis, inflammation, and the adaptive immune response (40); however, the exact role of these factors in T. pallidum dissemination remains to be determined. The identification of the proteolytic activity of pallilysin in the current study indicates that T. pallidum expresses at least one protease that is potentially involved in promoting bacterial dissemination in the ECM and via the circulatory system. Together, the binding and proteolytic results further implicate pallilysin as a critical factor in the virulence of T. pallidum by showing that it promotes the attachment to and degradation of important host molecules, thereby potentially facilitating colonization of and dissemination from various host infection sites. Genome sequencing indicated that T. pallidum has limited metabolic capabilities, including a lack of amino acid biosynthesis pathways, but expresses an abundance of amino acid, carbohydrate, and cation transporters (24). Hence, binding and degradation of fibrinogen, laminin, and potentially other host factors into small peptides and amino acids may not only promote dissemination through inhibition of coagulation but may also be beneficial for the pathogen during infection by providing a rich nutrient source.

Gel-based analysis of heterologously expressed proteases often results in the appearance of multiple protein bands which may be due to degradation by E. coli proteases or autolysis (65, 77). The fact that pallilysin formed multiple bands when analyzed via SDS-PAGE following purification from both a lon and ompT protease-deficient E. coli expression strain and an insect secretory protein expression system suggests that the protease may be synthesized as a proprotein which undergoes self-lysis, resulting in cleavage of the disordered proline-rich N-terminal prodomain and generation of the mature active protease. Such an autocatalytic mechanism has been shown to be essential for the activation of thermolysin-like metalloproteases (5, 39), which are potent virulence factors of various pathogenic bacteria involved in extracellular protein degradation. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloprotease (MT1-MMP), a key protease involved in tumor cell invasion, is also activated via autocatalysis (63). In the current study, the possibility of autocatalytic activation of pallilysin is further supported by our fibrinogen degradation data which demonstrated that maximal proteolytic activity for full-length pallilysin is attained only following an 8 to 16-h lag period in vitro, as well as by MS analysis of the multiple pallilysin bands excised from SDS-polyacrylamide gels and by the fact that purified pallilysin continues to undergo further degradation during incubation with the host substrate.

The aforementioned extended proteolytic lag period, combined with the finding that near-equimolar concentrations of pallilysin are required for substrate degradation, indicates that the specific fibrinogenolytic activity of the recombinant protease in vitro is initially relatively modest but rapidly increases after 16 h. This may be due partially to the recombinant nature of the pallilysin protease that was utilized in this study, since we were able to demonstrate enhanced substrate proteolysis following cleavage of the terminal histidine tag. The full proteolytic potential of the native T. pallidum protease awaits further investigation.

A requirement for bacterial proteins involved in host-pathogen interactions is surface exposure. The identification of surface-exposed outer membrane proteins in T. pallidum has proven to be technically challenging and thus highly controversial due to the fragility arising from the unusual ultrastructure of this bacterium. In addition, several reports have provided evidence for a paucity of T. pallidum integral outer membrane proteins on the surface of this bacterium (14, 15, 44, 59, 76). Although not previously documented for T. pallidum, one potential strategy to achieve surface exposure is the anchorage of a lipid-modified cysteine residue within the N terminus of the protein to the bacterial membrane, as is found in many bacteria, including the related spirochetes Borrelia burgdorferi and Leptospira (28). To investigate the possibility that pallilysin exists as a lipoprotein within T. pallidum, the current study determined the lipidation state of heterologously expressed pallilysin. Previous labeling studies of T. pallidum proteins have utilized [3H]palmitate as the lipoprotein label (1, 4, 67, 69), and here we used an alternative click-chemistry-based technology originally developed for the global analysis of the palmitoylation of eukaryotic proteins (46) to demonstrate that heterologously expressed pallilysin is palmitoylated in the related spirochete T. phagedenis. This work represents the first report which has successfully adapted this eukaryotic palmitoylation profiling technique for the identification of protein lipidation in bacteria, thus representing a powerful new tool for studying both human and bacterial protein palmitoylation. The obtained palmitoylation results for pallilysin confirm a previous in silico analysis that suggested that this protein exists as a lipoprotein within T. pallidum (66). This result, when combined with the results from a previous study that demonstrated surface exposure of heterologously expressed Tp0751 within T. phagedenis (11), suggests the possibility that pallilysin is a surface-exposed protease within T. pallidum that is lipidated via palmitoylation of the cysteine residue at position 24 and is, through this cellular location, capable of interacting with host components.

Treponema pallidum has been referred to as the “stealth pathogen” due to its ability to cause lifetime latent infection. A previous study, which examined a group of six recombinant T. pallidum proteins for their sensitivities and specificities with sera from patients with syphilis, detected a low antibody response to Tp0751/pallilysin (75). In this study, ELISA-based assays showed 25 of the 43 tested syphilis patient sera, at all stages of disease, failed to recognize Tp0751/pallilysin. At least four studies have detected antibodies specific for Tp0751/pallilysin during the course of natural and experimental syphilis (7, 8, 49, 75), indicating that the protein is expressed during infection. Although reverse transcriptase PCR studies have shown that tp0751 is transcribed in T. pallidum, Western blot analyses have consistently failed to detect pallilysin expression in T. pallidum (S. Houston and C. E. Cameron, unpublished observations). Combined, these results suggest an inherent low immunogenicity and/or a low level of expression of pallilysin during infection. This feature, together with the host ECM binding (8, 9) and proteolysis capabilities presented herein, may help explain, at least in part, how this pathogen is able to evade the host immune response during widespread dissemination.

The limited effectiveness of current worldwide public health programs in controlling syphilis further underpins the need for developing a novel approach for halting increasing T. pallidum infection rates through an alternative means of syphilis prevention. The current study is the first published report to identify and isolate a palmitoylated T. pallidum protein that is capable of binding and degrading at least two important human proteins, namely, laminin and fibrinogen, that have potential roles in controlling disseminated bacterial infection. Future studies investigating the ability of pallilysin to bind and degrade a diverse array of human proteins and the mechanism of proteolysis will be essential in determining the contribution of this protein to the rapid widespread dissemination of this highly invasive human pathogen.

Acknowledgments

We thank Azad Eshghi for his methodological ideas and technical assistance regarding lipoprotein labeling and mass spectrometry, respectively, and for supplying the Leptospira putative KatE expression construct. We thank Joanna Crawford for performing the insect protein expression.

This work was funded by Public Health Service grant AI-051334 from the National Institutes of Health, as well as by awards from the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, and the British Columbia Knowledge Development Fund. Support for this research was also provided in part by the BC Proteomics Network. C.E.C. is a Canada Research Chair in Molecular Pathogenesis and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar.

Editor: S. R. Blanke

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akins, D. R., B. K. Purcell, M. M. Mitra, M. V. Norgard, and J. D. Radolf. 1993. Lipid modification of the 17-kilodalton membrane immunogen of Treponema pallidum determines macrophage activation as well as amphiphilicity. Infect. Immun. 61:1202-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bamford, C. V., J. C. Fenno, H. F. Jenkinson, and D. Dymock. 2007. The chymotrypsin-like protease complex of Treponema denticola ATCC 35405 mediates fibrinogen adherence and degradation. Infect. Immun. 75:4364-4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baseman, J. B., and E. C. Hayes. 1980. Molecular characterization of receptor binding proteins and immunogens of virulent Treponema pallidum. J. Exp. Med. 151:573-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belisle, J. T., M. E. Brandt, J. D. Radolf, and M. V. Norgard. 1994. Fatty acids of Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins. J. Bacteriol. 176:2151-2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bitar, A. P., M. Cao, and H. Marquis. 2008. The metalloprotease of Listeria monocytogenes is activated by intramolecular autocatalysis. J. Bacteriol. 190:107-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boschwitz, J. S., and J. F. Timoney. 1994. Inhibition of C3 deposition on Streptococcus equi subsp. equi by M protein: a mechanism for survival in equine blood. Infect. Immun. 62:3515-3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinkman, M. B., et al. 2006. Reactivity of antibodies from syphilis patients to a protein array representing the Treponema pallidum proteome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:888-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cameron, C. E. 2003. Identification of a Treponema pallidum laminin-binding protein. Infect. Immun. 71:2525-2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron, C. E., N. L. Brouwer, L. M. Tisch, and J. M. Kuroiwa. 2005. Defining the interaction of the Treponema pallidum adhesin Tp0751 with laminin. Infect. Immun. 73:7485-7494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron, C. E., E. L. Brown, J. M. Kuroiwa, L. M. Schnapp, and N. L. Brouwer. 2004. Treponema pallidum fibronectin-binding proteins. J. Bacteriol. 186:7019-7022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron, C. E., et al. 2008. Heterologous expression of the Treponema pallidum laminin-binding adhesin Tp0751 in the culturable spirochete Treponema phagedenis. J. Bacteriol. 190:2565-2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffey, A., B. van den Burg, R. Veltman, and T. Abee. 2000. Characteristics of the biologically active 35-kDa metalloprotease virulence factor from Listeria monocytogenes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88:132-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conlan, J. W., A. Baskerville, and L. A. Ashworth. 1986. Separation of Legionella pneumophila proteases and purification of a protease which produces lesions like those of Legionnaires' disease in guinea pig lung. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:1565-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox, D. L., P. Chang, A. W. McDowall, and J. D. Radolf. 1992. The outer membrane, not a coat of host proteins, limits antigenicity of virulent Treponema pallidum. Infect. Immun. 60:1076-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox, D. L., et al. 27 September 2010. Surface immunolabeling and consensus computational framework to identify candidate rare outer membrane proteins of Treponema pallidum. Infect. Immun. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00834-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Crawford, J., et al. 2010. Structural and functional characterization of SporoSAG: a SAG2-related surface antigen from Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 285:12063-12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cumberland, M. C., and T. B. Turner. 1949. The rate of multiplication of Treponema pallidum in normal and immune rabbits. Am. J. Syph. Gonorrhea Vener. Dis. 33:201-212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis, S. L., S. Gurusiddappa, K. W. McCrea, S. Perkins, and M. Hook. 2001. SdrG, a fibrinogen-binding bacterial adhesin of the microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules subfamily from Staphylococcus epidermidis, targets the thrombin cleavage site in the Bβ chain. J. Biol. Chem. 276:27799-27805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellen, R. P., K. S. Ko, C. M. Lo, D. A. Grove, and K. Ishihara. 2000. Insertional inactivation of the prtP gene of Treponema denticola confirms dentilisin's disruption of epithelial junctions. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:581-586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eshghi, A., P. A. Cullen, L. Cowen, R. L. Zuerner, and C. E. Cameron. 2009. Global proteome analysis of Leptospira interrogans. J. Proteome Res. 8:4564-4578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzgerald, T. J., J. N. Miller, and J. A. Sykes. 1975. Treponema pallidum (Nichols strain) in tissue cultures: cellular attachment, entry, and survival. Infect. Immun. 11:1133-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzgerald, T. J., and L. A. Repesh. 1985. Interactions of fibronectin with Treponema pallidum. Genitourin. Med. 61:147-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitzgerald, T. J., L. A. Repesh, D. R. Blanco, and J. N. Miller. 1984. Attachment of Treponema pallidum to fibronectin, laminin, collagen IV, and collagen I, and blockage of attachment by immune rabbit IgG. Br. J. Vener. Dis. 60:357-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fraser, C. M., et al. 1998. Complete genome sequence of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Science 281:375-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fushimi, N., C. E. Ee, T. Nakajima, and E. Ichishima. 1999. Aspzincin, a family of metalloendopeptidases with a new zinc-binding motif. Identification of new zinc-binding sites (His128, His132, and Asp164) and three catalytically crucial residues (Glu129, Asp143, and Tyr106) of deuterolysin from Aspergillus oryzae by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 274(34):24195-24201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerbase, A. C., J. T. Rowley, D. H. Heymann, S. F. Berkley, and P. Piot. 1998. Global prevalence and incidence estimates of selected curable STDs. Sex. Transm. Infect. 74(Suppl. 1):S12-S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh, A., et al. 2006. Enterotoxigenicity of mature 45-kilodalton and processed 35-kilodalton forms of hemagglutinin protease purified from a cholera toxin gene-negative Vibrio cholerae non-O1, non-O139 strain. Infect. Immun. 74:2937-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haake, D. A. 2000. Spirochaetal lipoproteins and pathogenesis. Microbiology 146(7):1491-1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris, T. O., D. W. Shelver, J. F. Bohnsack, and C. E. Rubens. 2003. A novel streptococcal surface protease promotes virulence, resistance to opsonophagocytosis, and cleavage of human fibrinogen. J. Clin. Invest. 111:61-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayes, N. S., K. E. Muse, A. M. Collier, and J. B. Baseman. 1977. Parasitism by virulent Treponema pallidum of host cell surfaces. Infect. Immun. 17:174-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hazlett, K. R., et al. 2005. TP0453, a concealed outer membrane protein of Treponema pallidum, enhances membrane permeability. J. Bacteriol. 187:6499-6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henschen, A., F. Lottspeich, M. Kehl, and C. Southan. 1983. Covalent structure of fibrinogen. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 408:28-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho, H. Y., R. Rohatgi, L. Ma, and M. W. Kirschner. 2001. CR16 forms a complex with N-WASP in brain and is a novel member of a conserved proline-rich actin-binding protein family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:11306-11311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holland, D. R., A. C. Hausrath, D. Juers, and B. W. Matthews. 1995. Structural analysis of zinc substitutions in the active site of thermolysin. Protein Sci. 4:1955-1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imamura, T., et al. 1995. Effect of free and vesicle-bound cysteine proteinases of Porphyromonas gingivalis on plasma clot formation: implications for bleeding tendency at periodontitis sites. Infect. Immun. 63:4877-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishihara, K., T. Miura, H. K. Kuramitsu, and K. Okuda. 1996. Characterization of the Treponema denticola prtP gene encoding a prolyl-phenylalanine-specific protease (dentilisin). Infect. Immun. 64:5178-5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin, F., et al. 2005. Epidemic syphilis among homosexually active men in Sydney. Med. J. Aust. 183:179-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kent, M. E., and F. Romanelli. 2008. Reexamining syphilis: an update on epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Ann. Pharmacother. 42:226-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kooi, C., C. R. Corbett, and P. A. Sokol. 2005. Functional analysis of the Burkholderia cenocepacia ZmpA metalloprotease. J. Bacteriol. 187:4421-4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lafond, R. E., and S. A. Lukehart. 2006. Biological basis for syphilis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:29-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larsen, K. S., and D. S. Auld. 1991. Characterization of an inhibitory metal binding site in carboxypeptidase A. Biochemistry 30:2613-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levi, M., T. van der Poll, and H. R. Buller. 2004. Bidirectional relation between inflammation and coagulation. Circulation 109:2698-2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li, L., T. Binz, H. Niemann, and B. R. Singh. 2000. Probing the mechanistic role of glutamate residue in the zinc-binding motif of type A botulinum neurotoxin light chain. Biochemistry 39(9):2399-2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu, J., et al. 17 September 2010. Cellular architecture of Treponema pallidum: novel flagellum, periplasmic cone, and cell envelope as revealed by cryo electron tomography. J. Mol. Biol. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Lukehart, S. A., S. A. Baker-Zander, and S. Sell. 1980. Characterization of lymphocyte responsiveness in early experimental syphilis. I. In vitro response to mitogens and Treponema pallidum antigens. J. Immunol. 124:454-460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin, B. R., and B. F. Cravatt. 2009. Large-scale profiling of protein palmitoylation in mammalian cells. Nat. Methods 6:135-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsuka, Y. V., S. Pillai, S. Gubba, J. M. Musser, and S. B. Olmsted. 1999. Fibrinogen cleavage by the Streptococcus pyogenes extracellular cysteine protease and generation of antibodies that inhibit enzyme proteolytic activity. Infect. Immun. 67:4326-4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsumoto, K. 2004. Role of bacterial proteases in pseudomonal and serratial keratitis. Biol. Chem. 385:1007-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McKevitt, M., et al. 2005. Genome scale identification of Treponema pallidum antigens. Infect. Immun. 73:4445-4450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyoshi, S., and S. Shinoda. 2000. Microbial metalloproteases and pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 2:91-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moffat, J. F., P. H. Edelstein, D. P. Regula, Jr., J. D. Cirillo, and L. S. Tompkins. 1994. Effects of an isogenic Zn-metalloprotease-deficient mutant of Legionella pneumophila in a guinea-pig pneumonia model. Mol. Microbiol. 12:693-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Norman, M. U., et al. 2008. Molecular mechanisms involved in vascular interactions of the Lyme disease pathogen in a living host. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nusbaum, M. R., R. R. Wallace, L. M. Slatt, and E. C. Kondrad. 2004. Sexually transmitted infections and increased risk of co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 104:527-535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reference deleted.

- 55.Patti, J. M., B. L. Allen, M. J. McGavin, and M. Hook. 1994. MSCRAMM-mediated adherence of microorganisms to host tissues. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48:585-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pei, L., M. Palma, M. Nilsson, B. Guss, and J. I. Flock. 1999. Functional studies of a fibrinogen binding protein from Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Immun. 67:4525-4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poirier, T. P., M. A. Kehoe, E. Whitnack, M. E. Dockter, and E. H. Beachey. 1989. Fibrinogen binding and resistance to phagocytosis of Streptococcus sanguis expressing cloned M protein of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 57:29-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ponnuraj, K., et al. 2003. A “dock, lock, and latch” structural model for a staphylococcal adhesin binding to fibrinogen. Cell 115:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Radolf, J. D., M. V. Norgard, and W. W. Schulz. 1989. Outer membrane ultrastructure explains the limited antigenicity of virulent Treponema pallidum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:2051-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raiziss, G. W., and M. Severac. 1937. Rapidity with which Spirochaeta pallida invades the bloodstream. Arch. Dermatol. Syphilol. 35:1101-1109. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Righarts, A. A., I. Simms, L. Wallace, M. Solomou, and K. A. Fenton. 2004. Syphilis surveillance and epidemiology in the United Kingdom. Euro Surveill. 9:21-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riviere, G. R., D. D. Thomas, and C. M. Cobb. 1989. In vitro model of Treponema pallidum invasiveness. Infect. Immun. 57:2267-2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rozanov, D. V., and A. Y. Strongin. 2003. Membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase functions as a proprotein self-convertase. Expression of the latent zymogen in Pichia pastoris, autolytic activation, and the peptide sequence of the cleavage forms. J. Biol. Chem. 278:8257-8260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rybarczyk, B. J., S. O. Lawrence, and P. J. Simpson-Haidaris. 2003. Matrix-fibrinogen enhances wound closure by increasing both cell proliferation and migration. Blood 102:4035-4043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schlomann, U., et al. 2002. The metalloprotease disintegrin ADAM8. Processing by autocatalysis is required for proteolytic activity and cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 277:48210-48219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Setubal, J. C., M. Reis, J. Matsunaga, and D. A. Haake. 2006. Lipoprotein computational prediction in spirochaetal genomes. Microbiology 152:113-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shevchenko, D. V., et al. 1999. Membrane topology and cellular location of the Treponema pallidum glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase (GlpQ) ortholog. Infect. Immun. 67:2266-2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Supuran, C. T., A. Scozzafava, and A. Mastrolorenza. 2001. Bacterial proteases: current therapeutic use and future prospects for the development of novel antibiotics. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 11:221-259. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Swancutt, M. A., J. D. Radolf, and M. V. Norgard. 1990. The 34-kilodalton membrane immunogen of Treponema pallidum is a lipoprotein. Infect. Immun. 58:384-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thomas, D. D., J. B. Baseman, and J. F. Alderete. 1985. Fibronectin mediates Treponema pallidum cytadherence through recognition of fibronectin cell-binding domain. J. Exp. Med. 161:514-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thomas, D. D., A. M. Fogelman, J. N. Miller, and M. A. Lovett. 1989. Interactions of Treponema pallidum with endothelial cell monolayers. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 5:15-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomas, D. D., et al. 1988. Treponema pallidum invades intercellular junctions of endothelial cell monolayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:3608-3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Twining, S. S. 1984. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled casein assay for proteolytic enzymes. Anal. Biochem. 143:30-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Uitto, V. J., D. Grenier, E. C. Chan, and B. C. McBride. 1988. Isolation of a chymotrypsinlike enzyme from Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 56:2717-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Van Voorhis, W. C., et al. 2003. Serodiagnosis of syphilis: antibodies to recombinant Tp0453, Tp92, and Gpd proteins are sensitive and specific indicators of infection by Treponema pallidum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3668-3674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Walker, E. M., G. A. Zampighi, D. R. Blanco, J. N. Miller, and M. A. Lovett. 1989. Demonstration of rare protein in the outer membrane of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum by freeze-fracture analysis. J. Bacteriol. 171:5005-5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Witte, V., N. Wolf, T. Diefenthal, G. Reipen, and H. Dargatz. 1994. Heterologous expression of the clostripain gene from Clostridium histolyticum in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis: maturation of the clostripain precursor is coupled with self-activation. Microbiology 140(5):1175-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu, J. H., and S. L. Diamond. 1995. A fluorescence quench and dequench assay of fibrinogen polymerization, fibrinogenolysis, or fibrinolysis. Anal. Biochem. 224:83-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]