Abstract

Subtilase cytotoxin (SubAB) is the prototype of a new family of AB5 cytotoxins produced by Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli. Its cytotoxicity is due to its capacity to enter cells and specifically cleave the essential endoplasmic reticulum chaperone BiP. Previous studies have shown that intraperitoneal injection of mice with purified SubAB causes a pathology that overlaps with that seen in human cases of hemolytic-uremic syndrome, as well as dramatic splenic atrophy, suggesting that leukocytes are targeted. Here we investigated SubAB-induced leukocyte changes in the peritoneal cavity, blood, and spleen. After intraperitoneal injection, SubAB bound peritoneal leukocytes (including T and B lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages). SubAB elicited marked leukocytosis, which peaked at 24 h, and increased neutrophil activation in the blood and peritoneal cavity. It also induced a marked redistribution of leukocytes among the three compartments: increases in leukocyte subpopulations in the blood and peritoneal cavity coincided with a significant decline in splenic cells. SubAB treatment also elicited significant increases in the apoptosis rates of CD4+ T cells, B lymphocytes, and macrophages. These findings indicate that apart from direct cytotoxic effects, SubAB interacts with cellular components of both the innate and the adaptive arm of the immune system, with potential consequences for disease pathogenesis.

Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC) causes severe gastrointestinal infections in humans, which may progress to hemorrhagic colitis and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), a life-threatening combination of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal failure (14, 19). These clinical manifestations have long been considered to be largely attributable to the effects of Shiga toxin (Stx) on microvascular endothelial cells (19). However, some STEC strains produce an additional AB5 cytotoxin named subtilase cytotoxin (SubAB), which has the potential to make a major contribution to the pathogenesis of HUS in its own right. SubAB was initially detected in a locus of enterocyte effacement-negative O113:H21 STEC strain responsible for a small outbreak of HUS in South Australia (17, 18), but it is also produced by numerous other disease-causing STEC serotypes (8, 16, 17). SubAB is extraordinarily toxic for eukaryotic cells, and its mechanism of action involves highly specific A-subunit-mediated proteolytic cleavage of the essential endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone BiP (GRP78) (15). This triggers a massive ER stress response, ultimately leading to apoptosis (11, 12, 26).

Our recent in vitro studies have shown that SubAB also increases tissue factor-dependent factor Xa generation by cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells and human macrophages, suggesting a direct procoagulant effect (25). In mice, intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of purified SubAB causes microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal impairment, characteristics typical of Stx-induced HUS (24). Histological examination of organs removed from SubAB-treated mice revealed extensive microvascular thrombosis and other histological damage in the brain, kidneys, and liver, as well as dramatic splenic atrophy. Levels of peripheral blood leukocytes were raised at 24 h; there was also significant neutrophil infiltration in the liver, kidneys, and spleen, and toxin-induced apoptosis at these sites (24). These findings raise the possibility of pathologically significant direct interactions between SubAB and various leukocyte subsets, including immune cell activation and induction of inflammatory responses. Accordingly, we have now conducted a detailed examination of the effects of SubAB on leukocytes in toxin-treated mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Toxin purification.

SubAB holotoxin, its nontoxic derivative SubAA272B, and the isolated A and B toxin subunits (SubA and SubB) were purified from recombinant E. coli lysates by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) chromatography as described previously (17, 21). Purified proteins were fluorescently labeled with Oregon green (OG) as described previously (3).

Mice.

Animal experimentation was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Adelaide. Male BALB/c mice, 5 to 6 weeks old, were injected i.p. with 5 μg purified SubAB (dissolved in 200 μl of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]). Control mice received 200 μl PBS.

Detection of SubAB in peritoneal leukocytes.

At various times post-SubAB injection, mice were anesthetized by inhalation of halothane. Peritoneal leukocytes were harvested by washing the peritoneal cavity three times with 3 ml of ice-cold PBS. The leukocyte suspensions were washed twice in 10 ml ice-cold PBS and were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight at 4°C. The fixed leukocytes were washed, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 min, and then incubated with Fc blocker (5 μl of 10-mg/ml mouse gamma globulin per 1 million cells; D609-0100; Rockland) at 4°C for 30 min to minimize any nonspecific binding.

For immunofluorescence labeling, 1 million cells were transferred to a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) tube (35-2008; BD Falcon) and were incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-SubA or a control rabbit serum, followed by biotinylated goat anti-rabbit Ig (BA1000; Vector) and R-phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated streptavidin (016-110-084; Jackson ImmunoResearch). To identify the leukocyte subpopulation that SubAB attacks, the cells were double labeled for SubAB and different leukocyte markers. The leukocyte markers were labeled with rat anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies (see below) that were detected with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated donkey anti-rat Ig (712-096-153; Jackson ImmunoResearch). The mouse leukocyte surface markers examined were CD4 (helper T lymphocytes), CD8 (cytotoxic T lymphocytes), B220 (B lymphocytes), F4/80 (mainly macrophages), and Ly-6G (granulocyte-restricted cells, mainly neutrophils). Rat anti-CD4, anti-CD8, and anti-Ly-6G were purchased from BD Biosciences, PharMingen (catalog no. 553649, 553039, and 551459); rat anti-B220 and anti-F4/80 were in-house hybridoma supernatants (clones RA3-682 and A3-1). The labeled cells were analyzed immediately using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and CellQuest Pro (version 4.0.1) and Weasel (version 2.6) software. SubAB-related fluorescence (PE; excitation at 565 nm and emission at 575 nm) was detected via channel FL2, and leukocyte marker-related fluorescence (FITC; excitation at 490 nm and emission at 525 nm) was detected via channel FL1.

Leukocyte quantitation and assessment of apoptosis.

At different times post-SubAB injection, mice were anesthetized by inhalation of halothane, and blood was drawn via cardiac puncture and was collected into EDTA tubes. Blood leukocytes were separated by lysing the red blood cells (RBC) with a hypotonic shock. Peritoneal leukocytes were collected as described above. To harvest splenocytes, spleens were removed, placed on cell strainers (70-μm-pore size nylon mesh; BD Falcon reference no. 352350) resting in a 35-mm-diameter tissue culture dish containing 1 ml of ice-cold PBS, and cut into small pieces with scissors, followed by gentle homogenization with the plunger of a 3-ml syringe. Splenocytes were collected and were washed in ice-cold PBS. To obtain total leukocyte counts, blood, peritoneal, and spleen leukocytes were counted using a hemocytometer with a light microscope.

Apoptotic and necrotic cells were differentiated by staining live cells on ice with annexin V-Fluos (FITC-conjugated annexin V; catalog no. 1 828 681; Roche) and propidium iodide (PI) (P4170; Sigma). One million freshly harvested leukocytes were washed with ice-cold annexin V binding buffer (8.78 g/liter NaCl, 0.38 g/liter KCl, 0.2 g/liter MgCl2, 2 g/liter CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4]), resuspended in 50 μl of annexin V working reagent (consisting of 1/50 annexin V-Fluos and 1 μg/ml of PI in annexin V binding buffer), and incubated on ice in the dark for 30 min. Cells were then washed and were analyzed immediately on a FACscan flow cytometer. Fluorescence related to annexin V-FITC was read via the FL1 channel, and the fluorescence of PI (excitation at 536 nm; emission at 617 nm) was read via the FL3 channel.

Apoptosis in subpopulations of leukocytes was detected by double labeling of live cells with annexin V and anti-leukocyte markers (as indicated in the figures). Leukocytes were first incubated with monoclonal rat anti-mouse leukocyte markers, followed by biotinylated donkey anti-rat Ig (621-706-120; Rockland), and were then incubated simultaneously with PE-conjugated streptavidin and annexin V-FITC. All incubations were carried out in the dark on ice at 4°C for 30 min. Labeled cells were analyzed immediately on a FACscan flow cytometer. The fluorescence of FITC-annexin V was read via channel FL1, and leukocyte marker-related fluorescence (PE) was detected via channel FL2.

In vitro binding of SubAB to leukocytes.

Mouse peritoneal or blood leukocytes were freshly harvested and pooled from 2 normal mice, as described above. Leukocytes were then washed and resuspended in complete leukocyte culture medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, and 100 μg/ml of penicillin and streptomycin). One million peritoneal or blood leukocytes, resuspended in 500 μl complete leukocyte culture medium containing 1 μg/ml OG-labeled SubAB or labeled control proteins (OG-SubA, OG-SubB, OG-SubAA272B, or OG-ovalbumin [unlabeled ovalbumin was obtained from Sigma]), were cultured at 37°C under 95% air-5% CO2 for 90 min. Cells cultured in medium only (no OG-labeled protein added) were used as negative controls. Labeling of cells was stopped by the addition of 500 μl of 4% formaldehyde, and the cells either were washed with ice-cold PBS and were then analyzed by flow cytometry or underwent further leukocyte surface marker labeling as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 3.03) or Microsoft Excel 2003 software. FACS data are presented as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM), and differences between cells from control and SubAB-treated mice were analyzed using Student's unpaired t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Binding of SubAB by peritoneal leukocytes in vivo.

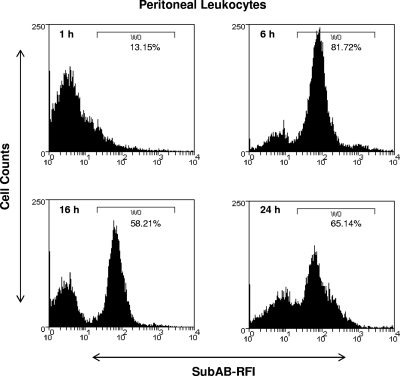

Initial experiments used flow cytometry to examine the binding and/or uptake of SubAB by murine peritoneal leukocytes at various times after i.p. injection of 5 μg toxin (Fig. 1). Bound or internalized toxin was detected using a polyclonal rabbit antibody raised against the A subunit of the toxin (SubA). SubAB binding/uptake was maximal at 6 h postinjection, at which time approximately 82% of the leukocyte population was labeled; at 16 and 24 h, labeling was still substantial (58% and 65% of the total population, respectively). The specificity of the rabbit anti-SubA antibody was confirmed by comparing the FACS scan of peritoneal leukocytes from control (non-SubAB-treated) mice after labeling with anti-SubA, or from 6-h toxin-treated mice after labeling with nonimmune serum, with that from 6-h toxin-treated mice whose peritoneal leukocytes were labeled with anti-SubA (result not shown).

FIG. 1.

Binding of SubAB to peritoneal leukocytes. Mouse peritoneal leukocytes were harvested at the indicated times post-i.p. injection of 5 μg SubAB, washed, fixed, and then permeabilized. SubAB was labeled with rabbit anti-SubA, followed by biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG and streptavidin-PE, and leukocytes were analyzed by FACS. SubAB-related immunofluorescence is expressed as the relative fluorescence intensity (RFI). SubAB-positive cells (harvested from mice treated with SubAB) were defined by the histogram mark (W0), which was set with reference to controls (cells harvested from untreated mice at 0 h and labeled with anti-SubA, and cells harvested from SubAB-treated mice at 6 h and labeled with nonimmune rabbit serum [not shown]). Data are from a single experiment with one mouse per time point; a repeat experiment yielded essentially identical results (not shown).

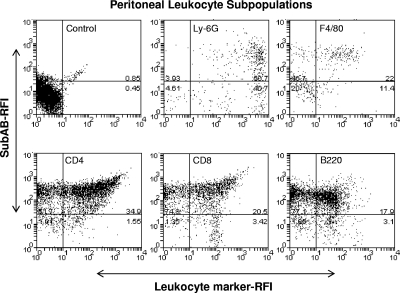

To examine whether the toxin bound preferentially to specific leukocyte subsets, peritoneal leukocytes harvested 6 h postinjection were double labeled with anti-SubA and various leukocyte marker-specific monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 2). The percentage of labeling for each subpopulation was calculated from the numbers in the upper right quadrant (leukocyte marker-high, SubAB-high cells) as a proportion of the total number of leukocyte marker-high cells (upper right quadrant plus lower right quadrant). SubAB was detected in all subpopulations, labeling 55% of neutrophils (Ly-6G+ cells), 66% of macrophages (F4/80+ cells), 96% of CD4+ T cells, 86% of CD8+ T cells, and 85% of B lymphocytes (B220+ cells).

FIG. 2.

SubAB binding by peritoneal leukocyte subpopulations. Mouse peritoneal leukocytes were harvested at 6 h post-SubAB (5 μg) injection, washed, and fixed. Cells were then permeabilized and double labeled with rabbit anti-SubA and rat anti-leukocyte markers (as indicated), followed by biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG and PE-conjugated streptavidin (for SubAB) or FITC-conjugated anti-rat IgG (for leukocyte markers). The labeled leukocytes were analyzed by FACS. The SubAB- or leukocyte marker-related immunofluorescence intensity is expressed as relative fluorescence intensity (RFI). Double-positive cells (upper right quadrants) were defined by quadrant marks set according to the distribution of control cells. The data shown are from experiments using cells from a single mouse.

Specificity of binding to leukocytes in vitro.

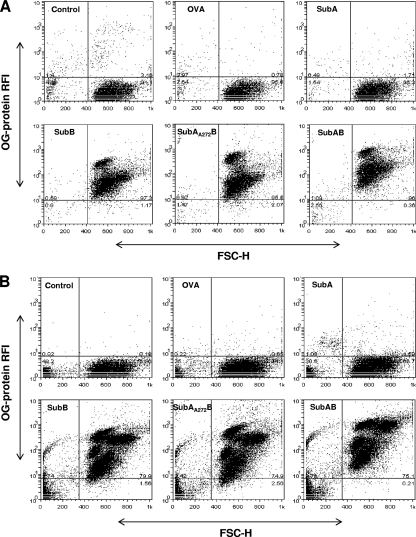

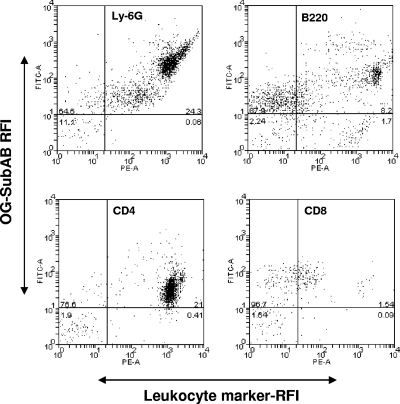

The findings discussed above suggested that SubAB could directly bind all leukocyte subsets after i.p. injection. As independent verification, we examined the capacity of OG-labeled SubAB and similarly labeled control proteins to interact with murine leukocytes in vitro. Peritoneal and peripheral blood leukocytes harvested from normal mice were cocultured for 90 min with 1 μg/ml OG-SubAB, OG-SubA, OG-SubB, OG-SubAA272B, or OG-ovalbumin and were then analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 3A and B). For both peritoneal and blood leukocytes, strong OG labeling was observed using OG-SubAB, OG-SubB, or OG-SubAA272B. However, there was no detectable labeling of leukocytes incubated with OG-SubA or OG-ovalbumin. This indicates that interaction with leukocytes derived from normal mice is absolutely dependent on the presence of the B subunit of the toxin. OG-SubAB-treated blood leukocytes were also double labeled with the leukocyte marker-specific monoclonal antibodies and were analyzed by flow cytometry (the percentage of labeling for each subset was calculated as described above for Fig. 2). As seen above for peritoneal leukocytes harvested from SubAB-injected mice, there was significant binding of labeled toxin to CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and neutrophils (98.1%, 94.5%, 82.3%, and 99.8% of the respective leukocyte subpopulations were positive for OG-SubAB binding) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Specificity of leukocyte binding. Peritoneal (A) and blood (B) leukocytes from normal mice were first cultured with 1 μg/ml OG-SubAB, OG-SubA, OG-SubB, OG-SubAA272B, or OG-ovalbumin (OVA) and then analyzed by flow cytometry, as described in Materials and Methods. Control cells were cultured without labeled protein. The data shown are from experiments using pooled cells harvested from two mice; a repeat experiment yielded essentially identical results (not shown).

FIG. 4.

In vitro binding of leukocyte subpopulations by OG-SubAB. Mouse blood leukocytes were first cultured with 1 μg/ml OG-SubAB and then incubated, in sequence, with rat anti-mouse leukocyte surface markers (Ly-6G, B220, CD4, and CD8) and with biotinylated donkey anti-rat Ig and PE-streptavidin. Leukocytes were subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. Cells in the upper right quadrant are double positive. The data shown are from experiments using cells pooled from two mice.

Effect of injection of SubAB on leukocyte distribution.

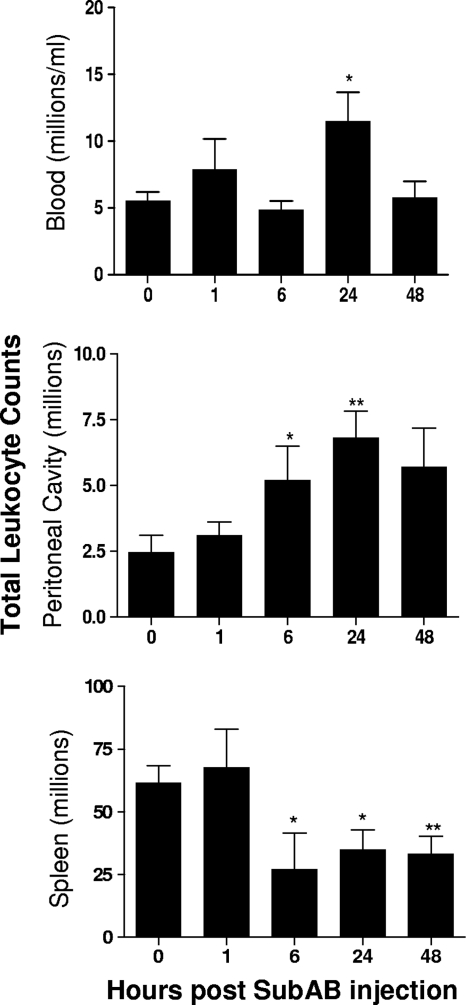

The total numbers and distribution of leukocyte subpopulations in the blood, peritoneal cavities, and spleens of mice were then examined at various times after SubAB injection (Fig. 5). Toxin treatment significantly increased the total numbers of peritoneal and blood leukocytes, which peaked at 24 h. However, a significant decrease in splenic leukocytes was evident from 6 h.

FIG. 5.

SubAB-induced changes in total leukocyte numbers. Mouse blood, peritoneal, and splenic leukocytes were harvested at the indicated times post-SubAB injection. Total leukocyte counts were determined using a hemocytometer. Nine, 6, 6, 8, and 5 mice were tested at 0, 1, 6, 24, and 48 h, respectively. The differences between the numbers of leukocytes at 0 h and at the various times postinjection were analyzed using Student's t test. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

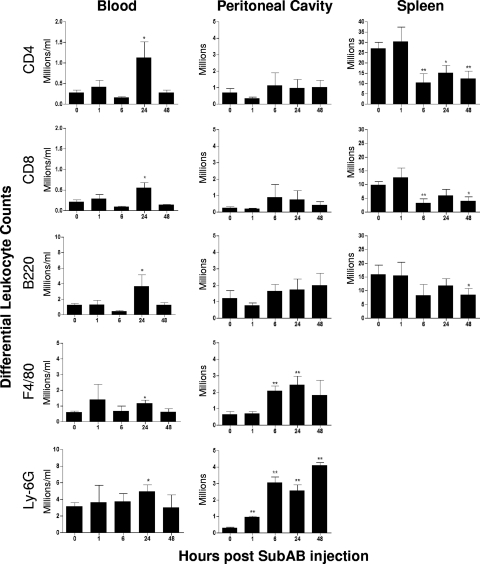

Immunofluorescence labeling and FACS analysis (Fig. 6) indicated that the increase in blood leukocytes was a consequence of significant increases in the absolute numbers of all five subpopulations (CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils) at 24 h (P, <0.05 in all cases). CD4+ cells also increased markedly as a percentage of total blood leukocytes, from 4.55% at 0 h to 8.94% at 24 h (P, <0.05). In the spleen, marked drops in the numbers of both the CD4+ and CD8+ subpopulations from 6 h (P, <0.01 in both cases) largely accounted for the decrease in total splenic leukocytes. The number of splenic B lymphocytes also decreased, although this decrease was statistically significant only at 48 h (P < 0.05). In the peritoneal cavity, where SubAB was injected, the total numbers of both neutrophils and macrophages increased swiftly. Significant neutrophil recruitment was evident from 1 h and was highest at 48 h (P < 0.01 for all time points). Macrophage numbers were significantly elevated at 6 h and peaked at 24 h (P < 0.01 in both cases). The number of neutrophils as a percentage of total peritoneal leukocytes also increased dramatically, from 20% at 0 h to 67% at 6 h postinjection.

FIG. 6.

SubAB-induced changes in differential leukocyte counts. Mouse blood, peritoneal, and splenic leukocytes were harvested and washed at the indicated times post-SubAB injection. They were then labeled with rat anti-leukocyte markers, followed by biotinylated anti-rat Ig and PE-streptavidin, and were analyzed by FACS. Nine, 6, 6, 8, and 5 mice were tested at 0, 1, 6, 24, and 48 h postinjection, respectively. The differences between the numbers of leukocytes at 0 h and at various times postinjection were analyzed using Student's t test. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

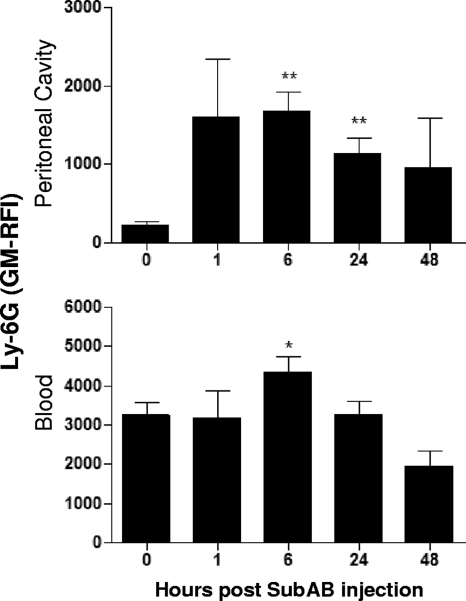

After SubAB injection, blood and peritoneal neutrophils increased not only in absolute numbers but also in the mean level of expression of the surface protein Ly-6G (Fig. 7), an indication of neutrophil maturation.

FIG. 7.

SubAB-induced changes in Ly-6G expression levels. Mouse blood and peritoneal leukocytes were harvested and washed at the indicated times post SubAB injection, incubated with rat anti-Ly-6G followed by biotinylated anti-rat IgG and PE-streptavidin, and analyzed by FACS. The Ly-6G-related fluorescence intensity is expressed as geometric mean relative fluorescence intensity (GM-RFI). Nine, 6, 6, 8, and 5 mice were tested at 0, 1, 6, 24, and 48 h postinjection, respectively. The differences between the values at 0 h and at the various times postinjection were analyzed using Student's t test. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Effect of SubAB on leukocyte apoptosis.

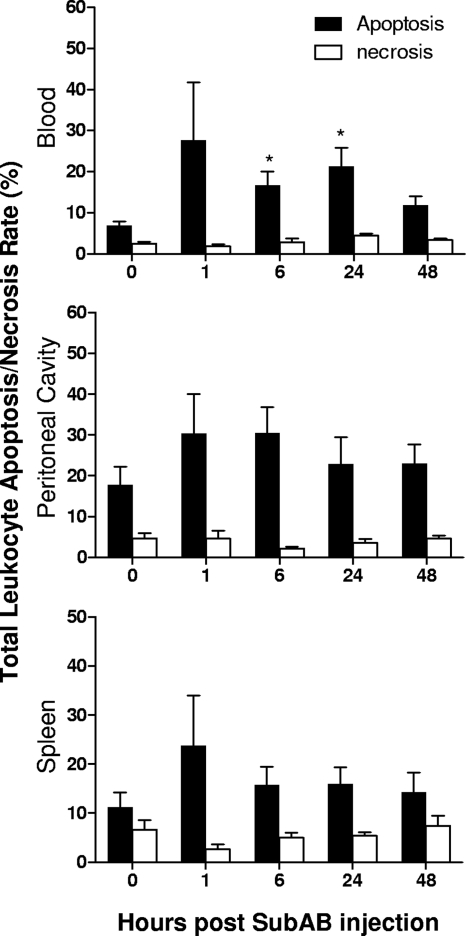

Double labeling with annexin V and PI was used to investigate the total rates of apoptosis and necrosis in the various niches after toxin treatment (Fig. 8). For the total leukocyte population, rates of necrosis remained low (below 7.4%) in all niches throughout the experiment. However, apoptosis rates were elevated from 1 h after toxin treatment and reached statistical significance for total blood leukocytes at 6 h and 24 h (P < 0.05).

FIG. 8.

SubAB-induced changes in the apoptosis/necrosis rates of leukocytes. Mouse blood, peritoneal, and splenic leukocytes were harvested and washed at the indicated times post-SubAB injection, double labeled with annexin V and propidium iodide, and then analyzed by FACS. Cells positive for annexin V only were classified as apoptotic; those double positive for annexin V and PI were classified as necrotic. Apoptosis and necrosis rates are expressed as percentages of the total leukocyte population. Nine, 6, 6, 8, and 5 mice were tested at 0, 1, 6, 24, and 48 h postinjection, respectively. The differences between the apoptosis rates at 0 h and at the various times postinjection were analyzed using Student's t test. *, P < 0.05.

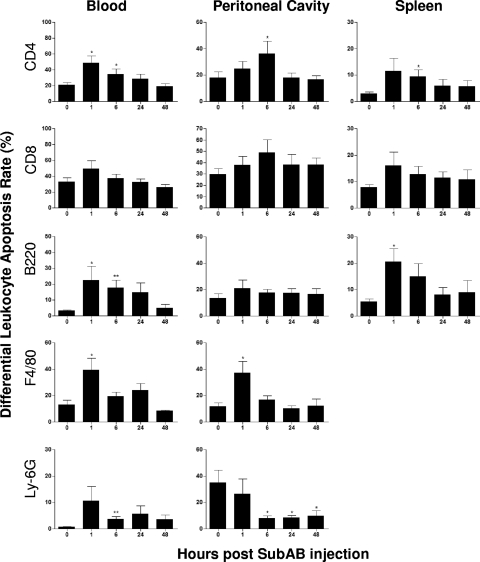

Double labeling with annexin V and anti-leukocyte markers was used to establish apoptosis rates in different subpopulations of leukocytes (Fig. 9). The apoptosis rates of blood CD4+ T cells and B220+ B cells were significantly elevated above baseline at 1 and 6 h. The apoptosis rates of splenic CD4+ T cells and B220+ B cells were also elevated at these time points, reaching statistical significance at 6 h and 1 h, respectively. In blood and the peritoneal cavity, apoptosis of macrophages was significantly elevated at 1 h but not thereafter. Interestingly, there was a marked difference in the baseline level of neutrophil apoptosis between blood and the peritoneal cavity (1% versus 34%, respectively). However, there was a marked and sustained reduction in the apoptosis rate of peritoneal neutrophils after toxin treatment, to approximately 8 to 10% at 6, 24, and 48 h (P < 0.05 in all cases). In contrast, the apoptosis rate of blood neutrophils, like that of most of the other leukocytes examined, was increased by toxin treatment from the low baseline level, reaching statistical significance at 6 h post-SubAB injection (P < 0.05).

FIG. 9.

SubAB-induced changes in the apoptosis rates of leukocyte subpopulations. Mouse blood, peritoneal, and splenic leukocytes were harvested and washed at the indicated times post-SubAB injection, double labeled for annexin V and leukocyte markers (as indicated), and then analyzed by FACS. Cells double positive for annexin V and a leukocyte marker were defined as apoptotic. The apoptosis rate is expressed as a percentage of the total number of cells in the respective subpopulation. Nine, 6, 6, 8, and 5 mice were tested at 0, 1, 6, 24, and 48 h postinjection, respectively. Differences between apoptosis rates at 0 h and at the various times postinjection were analyzed using Student's t test. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have examined the capacity of SubAB to interact with murine leukocytes after intraperitoneal injection of purified toxin. FACS analysis demonstrated specific binding to peritoneal leukocytes, peaking at 6 h postinjection but with significant amounts still detectable at 24 h. Double labeling with leukocyte markers demonstrated a lack of preference for any given subpopulation, with similar binding to CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils. The similar uptake by both phagocytic and nonphagocytic cell types suggested direct recognition of toxin receptors on the cell surface rather than phagocytosis. We have shown previously that the pentameric B subunit of SubAB has a high degree of specificity for sialated glycans terminating in α2-3-linked N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc). Crystallographic analysis of the toxin-receptor complex showed that the interaction is driven principally by this terminal sialic acid moiety, with minimal contribution from subterminal sugars (2). This accounted for a previous observation that SubAB could bind to several glycoprotein species, including α2β1 integrin, on the surfaces of Vero cells (27). Members of the integrin family are known to be heavily sialated and are expressed in abundance on the surfaces of all the leukocyte subsets discussed above (7). In the present study, we also confirmed that binding to the various leukocyte subpopulations is absolutely dependent on the presence of the toxin B subunit. The absence of binding of labeled ovalbumin by blood leukocytes in vitro also eliminates nonspecific phagocytosis as an explanation for the binding/uptake of toxin.

An important finding of the present study is the marked effect of toxin treatment on leukocyte distribution between host compartments. Total leukocyte counts in the peritoneal cavity increased nearly 3-fold by 24 h; the bulk of this increase consisted of macrophages and neutrophils presumably recruited to the site of toxin injection. In a separate in vitro study, we have shown that treatment of U937 (human macrophage) and Hct-8 (human colonic epithelial) cells with purified SubAB significantly upregulates the expression of CXC chemokines, particularly interleukin-8 (IL-8), macrophage inflammatory protein 2α (MIP-2α), and MIP-2β, all of which are potent neutrophil chemoattractants (unpublished data). An analogous response by murine macrophages and other resident peritoneal cells would explain the leukocyte influx observed in the present study. The effects of toxin injection were not confined to the peritoneal cavity; there was significant leukocytosis in the blood at 24 h. All leukocyte subpopulations measured were elevated at this time point, although the greatest relative increases over untreated baseline levels were seen for T and B lymphocytes. Nevertheless, blood neutrophil numbers were significantly elevated; moreover, there was a significant increase in mean Ly-6G expression on the surfaces of these cells, as well as on peritoneal neutrophils. The Ly-6G expression level has been reported to be directly proportional to neutrophil differentiation, maturation, and IL-1 receptor expression and hence is indicative of activation (1). Indeed, we have shown that treatment of U937 cells with SubAB upregulates the expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IL-1β in addition to the CXC chemokines mentioned above (unpublished data). It has long been known that neutrophil leukocytosis correlates with a poor outcome for HUS patients, and activated neutrophils play a key role in pathogenesis as mediators of endothelial injury (6).

The toxin-induced leukocytosis observed in the present study was accompanied by a marked reduction in the numbers of splenic lymphocytes, most notably CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The total numbers of splenic leukocytes decreased more than 2-fold within 6 h of toxin treatment, consistent with our previous histological observation of profound splenic atrophy and depletion of lymphocytes in the white pulp (24). This reduction was presumably a consequence of the combination of leukocyte migration into the peripheral circulation and significantly increased rates of apoptosis of both T and B lymphocytes. Increased apoptosis was a widespread toxin-induced phenomenon and was seen for all leukocyte subpopulations and at all sites examined. The only apparent exception to this was the significant decrease in apoptosis rates in peritoneal neutrophils, from an initially high baseline (0-h) level of 34% to 8% at 6 h postinjection. However, during this period there was massive recruitment of neutrophils from the peripheral circulation and presumably also the bone marrow, with total numbers in the peritoneal cavity increasing roughly 10-fold. Unsurprisingly, the level of apoptosis in peritoneal neutrophils at 6 h closely reflects that seen in peripheral blood neutrophils at the same time point.

Interestingly, injection of purified Stx2 has also been shown to induce neutrophilia and neutrophil activation in a murine model of HUS (5). Thus, our findings provide a further example of the similarities between the effects of the two toxins in vivo. In vitro studies have also shown binding of Stx1 and Stx2 to peripheral blood monocytes and monocytic cell lines, as well as Stx1-induced production of proinflammatory cytokines by these cells and by murine peritoneal macrophages (20, 22, 23). Stx1 has also been shown to block the activation and proliferation of lymphocytes (4, 13). The similarities in the properties of SubAB and Stx are remarkable given the fact that the two AB5 toxins are unrelated and have distinct host receptors, intracellular targets, and molecular mechanisms of action. The B subunit of SubAB mediates binding to Neu5Gc displayed on sialated glycoproteins (2), triggering clathrin-dependent internalization and retrograde transport via the Golgi complex to the ER lumen (3), where the proteolytic A subunit cleaves the essential Hsp70 family chaperone BiP (15). BiP is responsible for the proper folding of newly synthesized proteins, and as the master regulator of the ER stress response, it is essential for the maintenance of ER homeostasis (9). Cleavage of BiP triggers ER stress-signaling pathways and eventually leads to apoptosis (11, 12, 26). Stx, on the other hand, binds to the cell surface glycolipid Gb3 and follows a slightly different retrograde pathway to the Golgi complex and ER (4), after which the A subunit (an RNA-N-glycosidase) is retrotranslocated into the cytosol, where it modifies 28S rRNA and inhibits the elongation step of protein synthesis (19). Interestingly, in spite of this distinct mode of action, Stx1 has also been shown to trigger ER stress-mediated apoptosis in human monocytic cells (10).

The present study has provided the first evidence that leukocytes express functional receptors for SubAB and that the toxin induces in vivo inflammatory responses and leukocyte migration that could contribute to disease pathogenesis. The precise nature of the inflammatory responses elicited by SubAB in specific leukocyte subsets, and the extent to which these synergize with those triggered by Stx in the pathogenesis of human disease, remains a fertile field for future investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by program grant 565526 from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) and R01AI-068715 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health. J.C.P. is an NHMRC Australia Fellow.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bliss, S. K., B. A. Butcher, and E. Y. Denkers. 2000. Rapid recruitment of neutrophils containing prestored IL-12 during microbial infection. J. Immunol. 165:4515-4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byres, E., A. W. Paton, J. C. Paton, J. C. Löfling, and D. F. Smith, et al. 2008. Incorporation of a non-human glycan mediates human susceptibility to a bacterial toxin. Nature 456:648-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chong, D. C., J. C. Paton, C. M. Thorpe, and A. W. Paton. 2008. Clathrin-dependent trafficking of subtilase cytotoxin, a novel AB5 toxin that targets the ER chaperone BiP. Cell. Microbiol. 10:795-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferens, W. A., and C. J. Hovde. 2000. Antiviral activity of Shiga toxin 1: suppression of bovine leukemia virus-related spontaneous lymphocyte proliferation. Infect. Immun. 68:4462-4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández, G. C., et al. 2000. Shiga toxin-2 induces neutrophilia and neutrophil activation in a murine model of hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin. Immunol. 95:227-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsyth, K. D., A. C. Simpson, M. M. Fitzpatrick, T. M. Barratt, and R. J. Levinsky. 1989. Neutrophil-mediated endothelial injury in haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet ii:411-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris, E. S., T. M. McIntyre, S. M. Prescott, and G. A. Zimmerman. 2000. The leukocyte integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23409-23412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khaitan, A., D. M. Jandhyala, C. M. Thorpe, J. M. Ritchie, and A. W. Paton. 2007. The operon encoding SubAB, a novel cytotoxin, is present in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1374-1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee, A. S. 2001. The glucose-regulated proteins: stress induction and clinical applications. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:504-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, S. Y., M. S. Lee, R. P. Cherla, and V. L. Tesh. 2008. Shiga toxin 1 induces apoptosis through the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in human monocytic cells. Cell. Microbiol. 10:770-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuura, G., et al. 2009. Novel subtilase cytotoxin produced by Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli induces apoptosis in Vero cells via mitochondrial membrane damage. Infect. Immun. 77:2919-2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.May, K. L., J. C. Paton, and A. W. Paton. 2010. Escherichia coli subtilase cytotoxin induces apoptosis regulated by host Bcl-2 family proteins, Bax/Bak. Infect. Immun. 78:4691-4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menge, C., L. H. Wieler, T. Schlapp, and G. Baljer. 1999. Shiga toxin 1 from Escherichia coli blocks activation and proliferation of bovine lymphocyte subpopulations in vitro. Infect. Immun. 67:2209-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paton, A. W., et al. 2006. AB5 subtilase cytotoxin inactivates the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone BiP. Nature 443:548-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paton, A. W., and J. C. Paton. 2005. Multiplex PCR for direct detection of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli strains producing the novel subtilase cytotoxin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2944-2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paton, A. W., P. Srimanote, U. M. Talbot, H. Wang, and J. C. Paton. 2004. A new family of potent AB5 cytotoxins produced by Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Exp. Med. 200:35-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paton, A. W., M. C. Woodrow, R. M. Doyle, J. A. Lanser, and J. C. Paton. 1999. Molecular characterization of a Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli O113:H21 strain lacking eae responsible for a cluster of cases of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3357-3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paton, J. C., and A. W. Paton. 1998. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:450-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramegowda, B., and V. L. Tesh. 1996. Differentiation-associated toxin receptor modulation, cytokine production, and sensitivity to Shiga-like toxins in human monocytes and monocytic cell lines. Infect. Immun. 64:1173-1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talbot, U. M., J. C. Paton, and A. W. Paton. 2005. Protective immunization of mice with an active-site mutant of subtilase cytotoxin of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 73:4432-4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tesh, V. L., B. Ramegowda, and J. E. Samuel. 1994. Purified Shiga-like toxins induce expression of proinflammatory cytokines from murine peritoneal macrophages. Infect. Immun. 62:5085-5094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Setten, P. A., L. A. Monnens, R. G. Verstraten, L. P. van den Heuvel, and V. W. van Hinsbergh. 1996. Effects of verocytotoxin-1 on nonadherent human monocytes: binding characteristics, protein synthesis, and induction of cytokine release. Blood 88:174-183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, H., J. C. Paton, and A. W. Paton. 2007. Pathologic changes in mice induced by subtilase cytotoxin, a potent new Escherichia coli AB5 toxin that targets the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Infect. Dis. 196:1093-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, H., et al. 2010. Tissue factor-dependent procoagulant activity of subtilase cytotoxin, a potent AB5 toxin produced by Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 202:1415-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfson, J. J., et al. 2008. Subtilase cytotoxin activates PERK, IRE1 and ATF6 endoplasmic reticulum stress-signalling pathways. Cell. Microbiol. 10:1775-1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yahiro, K., et al. 2006. Identification and characterization of receptors for vacuolating activity of subtilase cytotoxin. Mol. Microbiol. 62:480-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]