Abstract

Rv1106c (hsd; 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase) is required by Mycobacterium tuberculosis for growth on cholesterol as a sole carbon source, whereas Rv3409c is not. Mutation of Rv1106c does not reduce Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth in infected macrophages or guinea pigs. We conclude that cholesterol is not required as a nutritional source during infection.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a nocardioform actinomycete and is a facultative intracellular bacterium that usually infects the host macrophage. M. tuberculosis has coevolved with humans and persists despite the actions of the immune system. Survival of M. tuberculosis requires adaptation to the host microenvironment (14). In the intracellular environment, M. tuberculosis shifts from a carbohydrate-based to a fatty acid-based metabolism (3, 15, 21), and in culture, M. tuberculosis will grow on cholesterol as the sole carbon source (18). One role for cholesterol in the intracellular environment could be as a source of carbon, e.g., catabolism to acetate and propionate (5, 24, 25). Additionally, cholesterol can serve as a building block for complex structures, e.g., lipids and hormones through anabolism.

Through transcriptional profiling (16, 24), bioinformatic analysis, and metabolic analysis of other actinomycetes (9), a partial metabolic pathway for cholesterol metabolism in M. tuberculosis has been sketched. The first step is the conversion of cholesterol to cholest-4-en-3-one (17) (Fig. 1). In Streptomyces spp. and Rhodococcus equi, this step is catalyzed by cholesterol oxidases, which share 60% amino acid identity and have structures and mechanisms that are nearly identical (13, 20). The closest M. tuberculosis homolog, Rv3409c, shares only 24% amino acid identity with the well-characterized cholesterol oxidases from Streptomyces and Rhodococcus. Although Mycobacterium smegmatis cellular lysates overexpressing Rv3409c were reported to contain cholesterol oxidase activity, characterization of the purified enzyme was not reported (4).

FIG. 1.

The reaction catalyzed by M. tuberculosis 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD).

Nocardia spp. (10, 12), proteobacteria (7), and most likely Rhodococcus jostii (19) utilize a 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase to catalyze the conversion of cholesterol to cholest-4-en-3-one. In M. tuberculosis, Rv1106c (hsd) is the closest homolog (75% identity with the Nocardia enzyme, UniProtKB ID Q03704). Indeed, we demonstrated in earlier work that Rv1106c encodes a functional 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) that can utilize cholesterol, pregnenolone, and dehydroepiandosterone as substrates (26). Here, we investigate the essentiality of these genes for growth of M. tuberculosis in vitro and in vivo.

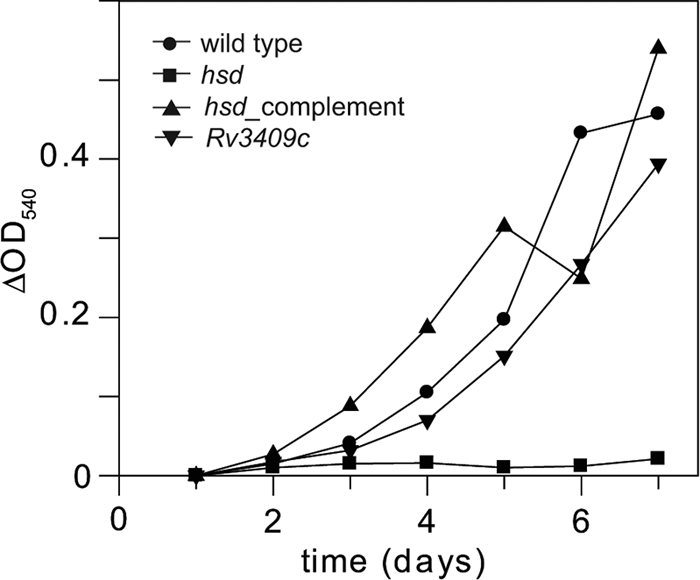

First, we tested whether in vitro growth with cholesterol as the carbon source required either Rv3409c or hsd. (Detailed experimental protocols may be found in the supplemental material.) We found that hsd is required for growth on cholesterol as a sole carbon source in broth culture, whereas the Rv3409c mutant grew as well as the wild type (Fig. 2). To further confirm the nonessentiality of Rv3409c for growth on cholesterol, we tested an M. smegmatis Rv3409c transposon mutant (myc11) (22) for growth on cholesterol as a sole carbon source on agar plates. The myc11 mutant formed colonies as readily as the mc2155 wild-type strain (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

hsd, but not Rv3409c, is required for growth on cholesterol as the sole carbon source. The strains were grown in 7H9 medium containing 1 mg ml−1 cholesterol (in tyloxapol) at 37°C. Data represent results of each experiment run in duplicate.

Complementation of the hsd mutant with the wild-type gene and 1,000 bases upstream of the open reading frame (26) completely restored growth on cholesterol (Fig. 2). All the strains grew normally in standard 7H9 medium supplemented with glycerol and 10% albumin-dextrose-NaCl complex (ADN) (data not shown). We conclude that hsd, but not Rv3409c, is required for growth on cholesterol as a sole carbon source.

Previously, we demonstrated that hsd is required for cholesterol oxidation activity in cell lysates (26). To investigate whether hsd is required for 3β-hydroxysterol oxidation in intact cells, the strains were grown in standard medium (7H9 liquid medium [Becton Dickinson], supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80, ADN [1], and 0.2% glycerol). After the cells reached log phase, 0.2 μCi of [4-14C]cholesterol was added. Five hours after cholesterol addition, lipids were extracted (2) and analyzed by liquid chromatography with scintillation counting and UV detection. Analysis of the wild-type cells revealed that >99% of the [14C]cholesterol was consumed within 5 h (Fig. 3 A). At the same time point, large amounts [14C]cholesterol (>40% of total counts) remained in the hsd mutant (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

hsd is required for the conversion of cholesterol to cholest-4-en-3-one by M. tuberculosis. Ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-UV analysis results are shown for the wild type, hsd mutant, and complemented hsd mutant. (A) M. tuberculosis was incubated for 5 h with [4-14C]cholesterol and analyzed by scintillation counting and UV absorbance. The cpm reflect the relative mass balance between samples. (B) M. tuberculosis was incubated for 5 h with cholesterol. The UV chromatographic profile from 3.6 to 3.9 min (shaded portion in panel A) is shown. The absorbance intensities do not reflect the relative mass balance between samples, which were concentrated to different extents for analysis. For the full profile and mass spectral analysis, see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material.

Nonradioactive samples were prepared in an analogous fashion (final concentration of cholesterol, 1 mg ml−1) for mass spectrometric analysis, which confirmed that the HSD reaction product, cholest-4-en-3-one, was formed in the wild-type cells (Fig. 3B; see also Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). However, no cholest-4-en-3-one could be detected in the hsd mutant by absorbance at 240 nm or single ion monitoring mass spectrometry (Fig. 3B; see also Fig. S1 and S2). Complementation of the hsd mutant strain restored production of cholest-4-en-3-one (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S1 and S2). As an additional control, Rv3409c was heterologously expressed to determine whether it was a cholesterol oxidase. Expression behind the acetamidase or heat shock hsp60 promoters in M. smegmatis mc2155 provided soluble protein upon induction (see Fig. S3 and S4 in the supplemental material). Despite assessment of the purified protein as both an oxidase (electron acceptor, O2) and a dehydrogenase (electron acceptor, phenazine methosulfate or 2,6-dichloroindophenol), no oxidation of cholesterol could be detected. On the basis of these complementary experiments, we concluded that HSD is required for conversion of cholesterol to cholest-4-en-3-one and that a second cholesterol oxidase activity is not present in M. tuberculosis.

Next, the role of hsd in M. tuberculosis growth in macrophages was assessed. Wild-type and mutant cultures were used to infect THP-1 cells that had been made to differentiate into macrophage-like cells with 40 nM 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (PMA) (23). No difference in the intracellular growth rate was detected (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Therefore, disruption of hsd does not limit M. tuberculosis replication in the macrophage.

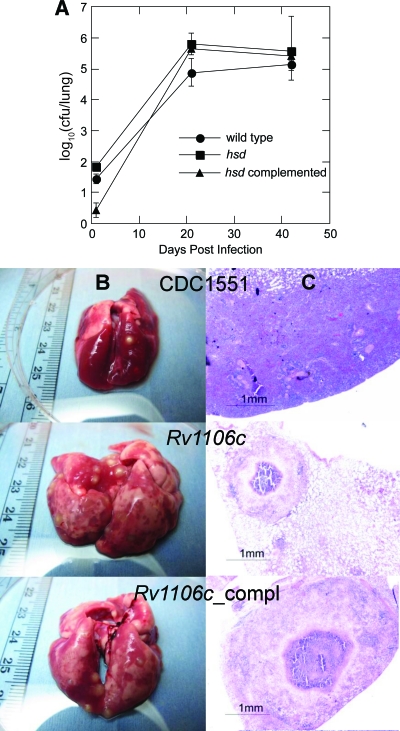

M. tuberculosis-infected guinea pigs develop granulomas similar to those seen in human disease. Therefore, the guinea pig model was employed to assess the in vivo role of hsd. The in vivo growth rate, lung weight, lung morphology, and lung histology were determined over a 6-week time course. No reduction in growth was observed in the mutant strain (Fig. 4). The number of granulomas in the lungs of animals infected by the hsd mutant and the complemented strain appeared to be higher than in the wild type (Fig. 4B and C). This difference may be the result of differing immune responses. Regardless, the hsd gene is not required for growth or survival of M. tuberculosis in the guinea pig. Moreover, if the buildup of cholesterol in the hsd mutant occurs during infection, as it does in vitro, the high level of cholesterol is not toxic to the bacterium. This result is in contrast to the toxicity of accumulated metabolites that is observed upon disruption of genes encoding ring-metabolizing enzymes later in the M. tuberculosis cholesterol pathway (6, 17, 25).

FIG. 4.

Mutation of hsd does not affect granuloma formation in the guinea pig model of infection. Fourteen guinea pigs were infected with ∼102 CFU/lung of each M. tuberculosis strain. At the indicated time points, four to six guinea pigs per strain were sacrificed, and lungs were weighed, a portion was excised for histology, and the remainder was homogenized for CFU titration. (A) M. tuberculosis growth rates in the lungs of aerosol-infected guinea pigs. Error bars are the standard deviations. (B) Gross pathology of lungs 42 days after infection. (C) Histopathology of the lungs shown in panel B.

In conclusion, we have established that the 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase encoded by Rv1106c (hsd) is required for growth on cholesterol as a sole carbon source, whereas the putative cholesterol oxidase, Rv3409c, is not. Lipidomics experiments have revealed that methyl-branched lipid carbon sources from the host are the primary source of nutrition in vivo for M. tuberculosis (11, 27). Our observation that hsd is not required for growth in the activated macrophage or in the guinea pig model of M. tuberculosis infection suggests that cholesterol is not a sole nutrition source in vivo. Moreover, fadA5, tentatively annotated as encoding a side chain-cleaving enzyme, is required for cholesterol metabolism and growth on cholesterol as a sole carbon source in vitro. Although FadA5 is not required for growth of M. tuberculosis in mice, it is required for maintenance in the host (16). These combined observations suggest that M. tuberculosis does not rely on cholesterol as a sole energy source in the host. Our results are consistent with the availability of multiple lipid energy sources in the host and with the recent work of Rhee and coworkers demonstrating that M. tuberculosis cocatabolizes multiple carbon sources (8).

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

Garcia and coworkers recently reported that M. smegmatis Rv3409c is not required for cholesterol mineralization (I. Uhia, B. Galán, V. Morales, and J. K. García, Environ. Microbiol., doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02398x, 2011).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (AI065251 to N.S.S., HL53306 to N.S.S., AI085349 to N.S.S., A1044856 to I.S., AI065987 to I.S., and NIH/NIAID NO1-AI30036 [TARGET contract]) and the New York State Technology and Research Program (FDP C040076, to N.S.S.).

We thank P. Chou for his work on the initial investigations of Rv3409c and J.-M. Reyrat for providing the myc11 mutant.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 January 2011.

Present address: Tuberculosis Research Section, CID/NIAID/NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belisle, J. T., L. Pascopella, J. M. Inamine, P. J. Brennan, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1991. Isolation and expression of a gene cluster responsible for biosynthesis of the glycopeptidolipid antigens of Mycobacterium avium. J. Bacteriol. 173:6991-6997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bligh, E. G., and W. J. Dyer. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37:911-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boshoff, H. I., and C. E. Barry. 2005. A low-carb diet for a high-octane pathogen. Nat. Med. 11:599-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brzostek, A., B. Dziadek, A. Rumijowska-Galewicz, J. Pawelczyk, and J. Dziadek. 2007. Cholesterol oxidase is required for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Lett. 275:106-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brzostek, A., J. Pawelczyk, A. Rumijowska-Galewicz, B. Dziadek, and J. Dziadek. 2009. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is able to accumulate and utilize cholesterol. J. Bacteriol. 191:6584-6591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, J. C., et al. 2009. igr genes and Mycobacterium tuberculosis cholesterol metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 191:5232-5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiang, Y. R., et al. 2008. Study of anoxic and oxic cholesterol metabolism by Sterolibacterium denitrificans. J. Bacteriol. 190:905-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Carvalho, L. P., et al. 2010. Metabolomics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals compartmentalized co-catabolism of carbon substrates. Chem. Biol. 17:1122-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donova, M. V. 2007. Transformation of steroids by actinobacteria: a review. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 43:1-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horinouchi, S., H. Ishizuka, and T. Beppu. 1991. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and transcriptional analysis of the NAD(P)-dependent cholesterol dehydrogenase gene from a Nocardia sp. and its hyperexpression in Streptomyces spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1386-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain, M., et al. 2007. Lipidomics reveals control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence lipids via metabolic coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:5133-5138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kishi, K., Y. Watazu, Y. Katayama, and H. Okabe. 2000. The characteristics and applications of recombinant cholesterol dehydrogenase. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64:1352-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreit, J., and N. S. Sampson. 2009. Cholesterol oxidase: physiological functions. FEBS J. 276:6844-6856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moller, M., E. de Wit, and E. G. Hoal. 2010. Past, present and future directions in human genetic susceptibility to tuberculosis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 58:3-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munoz-Elias, E. J., and J. D. McKinney. 2005. Mycobacterium tuberculosis isocitrate lyases 1 and 2 are jointly required for in vivo growth and virulence. Nat. Med. 11:638-644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nesbitt, N., et al. 2010. A thiolase of M. tuberculosis is required for virulence and for production of androstenedione and androstadienedione from cholesterol. Infect. Immun. 78:275-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouellet, H., et al. 2010. Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP125A1, a steroid C27 monooxygenase that detoxifies intracellularly generated cholest-4-en-3-one. Mol. Microbiol. 77:730-742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandey, A. K., and C. M. Sassetti. 2008. Mycobacterial persistence requires the utilization of host cholesterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:4376-4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosłoniec, K. Z., et al. 2010. Cytochrome P450 125 (CYP125) catalyzes C26-hydroxylation to initiate sterol side chain degradation in Rhodococcus jostii RHA1. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1031-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampson, N. S., and A. Vrielink. 2003. Cholesterol oxidases: a study of nature's approach to protein design. Acc. Chem. Res. 36:713-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segal, W., and H. Bloch. 1956. Biochemical differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis grown in vivo and in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 72:132-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonden, B., et al. 2005. Gap, a mycobacterial specific integral membrane protein, is required for glycolipid transport to the cell surface. Mol. Microbiol. 58:426-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsuchiya, S., et al. 1982. Induction of maturation in cultured human monocytic leukemia cells by a phorbol diester. Cancer Res. 42:1530-1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van der Geize, R., et al. 2007. A gene cluster encoding cholesterol catabolism in a soil actinomycete provides insight into Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:1947-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yam, K. C., et al. 2009. Studies of a ring-cleaving dioxygenase illuminate the role of cholesterol metabolism in the pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang, X., E. Dubnau, I. Smith, and N. S. Sampson. 2007. Rv1106c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 46:9058-9067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang, X., N. M. Nesbitt, E. Dubnau, I. Smith, and N. S. Sampson. 2009. Cholesterol metabolism increases the metabolic pool of propionate in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry 48:3819-3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.