Abstract

Bacterial small noncoding RNAs have attracted much interest in recent years as posttranscriptional regulators of genes involved in diverse pathways. Small RNAs (sRNAs) are 50 to 400 nucleotides long and exert their regulatory function by directly base pairing with mRNA targets to alter their stability and/or affect their translation. This base pairing is achieved through a region of about 10 to 25 nucleotides, which may be located at various positions along different sRNAs. By compiling a data set of experimentally determined target-binding regions of sRNAs and systematically analyzing their properties, we reveal that they are both more evolutionarily conserved and more accessible than random regions. We demonstrate the use of these properties for computational identification of sRNA target-binding regions with high specificity and sensitivity. Our results show that these predicted regions are likely to base pair with known targets of an sRNA, suggesting that pointing out these regions in a specific sRNA can help in searching for its targets.

Small noncoding RNAs are essential for the regulation of diverse processes in all kingdoms of life. The bacterial regulatory RNAs, usually referred to as “small RNAs” (sRNAs), vary in size between 50 and 400 nucleotides (63) and occasionally contain a short open reading frame (75). Many bacterial sRNAs exert their regulatory function by directly base pairing with mRNA targets to alter their stability and/or affect their translation (76). In most cases, base pairing between the sRNA and a target mRNA leads to instability of the mRNA and/or inhibition of translation initiation. However, a few bacterial sRNAs were reported to promote translation initiation, for example, by exposing a ribosome binding site that was otherwise occluded in a secondary structure (63). For many of the sRNAs, their hybridization with the mRNA is assisted by the chaperone Hfq, which binds both RNA molecules. The involvement of Hfq varies between species, being very well established in some species, such as Escherichia coli, and less common in others, such as Staphylococcus aureus (27). One role of this chaperon is to localize the regulator and target and assist in the hybridization between the two RNAs, which sometimes is shorter than one helical turn and might be interrupted (27).

In recent years, data on the interaction between bacterial sRNAs and their targets have accumulated for a growing number of sRNAs. These data provided clues as to the characteristics of the interaction and to the sRNA-mRNA binding region. A couple of sRNAs were shown to interact with their targets through their most 5′ end region (e.g., MicC [13] and OmrA [21]), while many sRNAs were shown to use other regions along the molecule for interaction with their targets. Most sRNAs were shown to use only one region for interacting with their targets, such as GcvB, which was shown to interact with at least seven targets through the same region, a G/U-rich region located in the central part of the molecule (58). However, there are also sRNAs that use different regions simultaneously to interact with one target, such as OxyS targeting fhlA (7), and sRNAs that use different regions for interaction with different targets, like FnrS, which uses either its 5′ end region or another central region to base pair with different targets (18). Also, the length of the hybridization region is not constant and might vary from one sRNA to another. Finally, in some cases, such as in the case of GcvB, the target-binding region was shown to be more evolutionarily conserved than the rest of the sRNA and more accessible (e.g., see reference 58). Thus, different reports characterized different aspects of the sRNA target-binding regions, but a comprehensive analysis of these regions applied to the whole body of accumulated data is still lacking.

A major challenge in sRNA research concerns the prediction of sRNA targets. To this end, several algorithms were developed, most of which either search for complementarity between sRNA and mRNA sequences, as in the work of Zhang et al. (79), or try to minimize the free energy of the hybridization between two RNAs, as in TargetRNA (66), RNAup (42), the work of Mandin et al. (37), IntaRNA (11), and the algorithms sRNATargetNB and sRNATargetSVM (80). Most of the above algorithms use additional data, like the secondary structure of the sRNA and/or the target in question (IntaRNA, RNAup, the work of Zhang et al. [79], and sRNATargetNB/SVM), or the nucleotide composition of the interacting regions (the work of Zhang et al. [79] and sRNATargetNB/SVM). Some algorithms make additional assumptions, such as of the existence of a consecutive base pairing between the two RNAs longer than a predefined value (IntaRNA and sRNA- TargetNB/SVM). Determination of the target-binding region of the sRNA could help in reducing the complexity and in alleviating the accuracy of these established algorithms.

In this study, we compiled a comprehensive list of experimentally determined sRNA target-binding regions in E. coli and analyzed their sequence and structural properties. We show that these regions differ in their level of conservation and site accessibility compared to non-target-binding regions of an sRNA. By determining the characteristic values of these features, we demonstrate their usefulness for identifying the binding regions of sRNAs based on sequence information, and for predicting, in turn, their mRNA targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compilation of small RNAs and their targets.

Sequences of E. coli sRNAs used in this analysis were retrieved from RefSeq (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/RefSeq/). Included were 23 sRNAs whose expression was experimentally verified and for which targets were reported. The targets of the different sRNAs were taken from Shimoni et al. (59) and were updated by a literature screen for all the papers published since then in which sRNA targets in E. coli or Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium were reported. Our database is consistent with the sRNATarBase (12), which was published in parallel to our compilation. As to the sRNA targets, the two databases are mostly equivalent; however, our definitions of the binding regions are more strict.

The sRNA targets, along with the methods used for their determination, are listed in Tables 1 and 2 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The target-binding region of an sRNA was defined by the nucleotides reported in the experimental paper as participating in the hybridization with a target mRNA. When RNase III cleavage or mutations were used to prove the interaction, the target-binding region was defined as the region cleaved by RNase III or the region in which mutations affected the regulation, along with the nucleotides surrounding this area that perfectly base pair with the target.

TABLE 1.

List of reliable target-binding regions in E. coli sRNAs

| sRNA | Target | Regulation | Evidencea | Experiment type for defining the interface | Binding positions on sRNA | Binding positions on mRNA | Binding sequencesc | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ArcZ | rpoS | Activation | a, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 64-71 | −104-−97 | CAAGAUUUCCCUGG | 36 |

| |||||||| | ||||||||

| UGCCUAAAGGGGAA | ||||||||

| ArcZ | sdaCb | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 70-74 | −13-−9 | UUCCCUGGUGU | 46 |

| ||||| | ||||||||

| AGAGGACCUCC | ||||||||

| ArcZ | tpxb | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 69-74 | +21-+26 | UUUCCCUGGUGU | 46 |

| |||||| | ||||||||

| AACGGGACCUUU | ||||||||

| ChiX | chiP | Repression | a, b, c, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 46-56 | −19-−8 | AAUUCCUCUUUGACGGGC | 52 |

| |||||||||||| | ||||||||

| AUUAGGAGAAACUGCAUA | ||||||||

| ChiX | dpiB | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 46-57 | −37-−26 | AUUCCUCUUUGACGGGCC | 19, 35 |

| |||||||||||| | ||||||||

| CUCGGAGAAACUGCCUAC | ||||||||

| CyaR | luxS | Repression | b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 42-49 | −12-−5 | GAACCACCUCCUUA | 15 |

| |||||||| | ||||||||

| AUCGGUGGAGGCCA | ||||||||

| CyaR | nadE | Repression | b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 39-49 | −11-−2 | CAGGAACCACCUCCUUA | 15 |

| |||||||||| | ||||||||

| UAACUUGG-GGAGGUCU | ||||||||

| CyaR | ompX | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 40-48 | −9-−1 | AGGAACCACCUCCUU | 15, 25, 45 |

| ||||||||| | ||||||||

| GUAUUGGUGGAGUUU | ||||||||

| CyaR | yqaE | Repression | b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 35-43 | +4-+12 | GUACCAGGAACCACC | 15 |

| ||||||||| | ||||||||

| AGAGGUCUUUGGGUA | ||||||||

| DsrA | hns | Repression | a, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 31-43 | +7-+19 | AUUUUUUAAGUGCUUCUUG | 31, 60, 68 |

| ||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| CUUAAAAUUCACGAAGCGA | ||||||||

| DsrA | rpoS | Activation | a, d, e, g, h | RNase III cleavage, | 10-16, 20-32 | −119-−107, −103-−97 | UCAGAUUUCCUGGUGUAACGAAUUUUUUA | 31, 33, 34, 36, |

| compensatory mutations | |||||||||||||||||||| | 54, 61 | ||||||

| UGCCUAAAGGGGAACAUUGCUUAAAGUUU | ||||||||

| FnrS | folE | Repression | a, b, d | sRNA mutations | 1-7 | −9-−3 | GCAGGUGAAU | 10, 18 |

| ||||||| | ||||||||

| GGACGUCCACACU | ||||||||

| FnrS | folX | Repression | a, b, d | sRNA mutations | 1-6 | −7-−2 | GCAGGUGAA | 10, 18 |

| |||||| | ||||||||

| UAACGUCCAAGA | ||||||||

| FnrS | gpmA | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 47-51 | −8-−4 | UGUCUUACUUC | 10, 18 |

| |||||| | ||||||||

| UAUGAAUGAGG | ||||||||

| FnrS | maeA | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 55-65 | −21-−11 | UUCCUUUUUUGAAUUAC | 18 |

| ||||||||||| | ||||||||

| UGAGAAAAAACUUAUAG | ||||||||

| FnrS | sodB | Repression | a, b, c, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 1-8 | +13-+20 | GCAGGUGAAUGC | 10, 18 |

| |||||||| | ||||||||

| UCACGUCCAUUAAG | ||||||||

| GcvB | dppA | Repression | a, b, f, g | Probing | 65-82 | −30-−14 | CGGUUGUGAUGUUGUGUUGUUGUG | 58, 66, 68, 70 |

| |||||||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| GUUAACACUACAA-ACAACAAAAU | ||||||||

| GcvB | argTb | Repression | a, b, f, g | Probing | 75-91 | −58-−43 | GUUGUGUUGUUGUGUUUGCAAUU | 58 |

| |||||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| UAACACAACA-CACAAACGUCCG | ||||||||

| GcvB | livJb | Repression | a, b, f, g | Probing | 63-87 | −45-−22 | TACGGUUGUGAUGUUGUGUUGUUGUGUUUGC | 58 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| AGACCAAUAAUGCA-CACAACACTACAACAA | ||||||||

| GcvB | livKb | Repression | a, b, f, g | Probing | 65-77 | −29-−17 | CGGUUGUGAUGUUGUGUUG | 58 |

| ||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| GUAAGCACUACAACACAAC | ||||||||

| GcvB | sstT | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 78-87 | −22-−13 | GUGUUGUUGUGUUUGC | 49 |

| |||||||||| | ||||||||

| GAAAGUAACACAACAG | ||||||||

| GlmZ | glmS | Activation | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 150-157, 163-169 | −40-−34, −29-−22 | CACUUGUUGUCAUACAGACCUGUUUU | 53, 69 |

| |||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| UAUAGCAACAGCCA-GUUGGACAUAC | ||||||||

| IstR-1 | tisB | Repression | b, d, e, g | Compensatory mutations | 1-22 | −14-+8 | GUUGACAUAAUACAGUGUGCUUUGC | 74 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| GAACAACUGUAUUGUGUCACACGAGUGC | ||||||||

| MicA | lamB2 | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 19-26 | +1-+8 | GUUAUCAUCAUCCC | 9 |

| |||||||| | ||||||||

| CAUUAGUAGUAAGA | ||||||||

| MicA | ompA | Repression | a, b, c, d, e, f, h | mRNA probing | 8-24 | −21-−6 | GACGCGCAUUUGUUAUCAUCAUC | 51, 67, 68 |

| |||||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| AAACGCG-GAGCAAUAGUAGGUU | ||||||||

| MicA | phoP | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 6-15 | −2-+8 | AAGACGCGCAUUUGUU | 14 |

| |||||||||| | ||||||||

| UCAUGCGCGUAAAAAU | ||||||||

| MicC | ompC | Repression | a, b, d, e, h | Compensatory mutations | 1-16 | −30-−15 | GUUAUAUGCCUUUAUUGUC | 13, 68 |

| |||||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| AGACAAUAUACGGAAAUAAACG | ||||||||

| MicF | ompF | Repression | a, b, c, f | Probing | 5-13, 21-33 | −16-+7 | CUAUCAUCAUUAACUUUAUUUAUUACCGUCAUUCA | 2, 5, 39, 50, |

| |||||||||||||||||||||| | 56, 68 | |||||||

| CGAAGUAGUAAU------AAAUAAUGGGAGUACCA | ||||||||

| OmrA | cirA | Repression | b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 5-10 | −19-−15 | CCAGAGGUAUUG | 21, 22 |

| |||||| | ||||||||

| GUACUCCAUUGA | ||||||||

| OmrA | csgD | Repression | a, b, d, e, f, h | Compensatory mutations | 2-15 | −74-−61 | CCCAGAGGUAUUGAUUGG | 24 |

| |||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| CGUGGUCUUCAUGACUGUCU | ||||||||

| OmrA | ompR | Repression | b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 1-9 | −19-−11 | CCCAGAGGUAUU | 21, 22 |

| ||||||||| | ||||||||

| UGAGGGUUUCCAAGC | ||||||||

| OmrA | ompT | Repression | b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 1-9 | +12-+20 | CCCAGAGGUAUU | 21, 22 |

| ||||||||| | ||||||||

| UAAGGGUCUUCAAAG | ||||||||

| OmrB | cirA | Repression | b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 5-10 | −19-−15 | CCAGAGGUAUUG | 21, 22 |

| |||||| | ||||||||

| GUACUCCAUUGA | ||||||||

| OmrB | csgD | Repression | a, b, d, e, f, h | Compensatory mutations | 2-20 | −79-−61 | CCCAGAGGUAUUGAUAGGUGAAG | 24 |

| ||||||||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| CGUGGUCUUCAUGACUGUCUACAAC | ||||||||

| OmrB | ompR | Repression | b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 1-9 | −19-−11 | CCCAGAGGUAUU | 21 |

| ||||||||| | ||||||||

| UGAGGGUUUCCAAGC | ||||||||

| OmrB | ompT | Repression | b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 1-9 | +12-+20 | CCCAGAGGUAUU | 21, 22 |

| ||||||||| | ||||||||

| UAAGGGUCUUCAAAG | ||||||||

| OxyS | fhlA | Repression | a, b, c, d, e, h | Compensatory mutations | 22-30, 98-104 | −15-−9, +34-+42 | UUUUAACCCUUGAAG | 4, 7 |

| ||||||||| | ||||||||

| CUUGUUGGGAACAAC | ||||||||

| AUCUCCAGGAUCC | ||||||||

| ||||||| | ||||||||

| AGAAGGUCCUUUC | ||||||||

| RprA | rpoS | Activation | a, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 33-37, 40-45, 55-62 | −117-−110, −106-−101, −98-−94 | AGCAUGGAAAUCCCCUGAG | 32, 34, 36 |

| ||||||||||| | ||||||||

| AAAUGCCUAAAGGGGAAC | ||||||||

| UGAAACAACGAAUUGCU | ||||||||

| |||||||| | ||||||||

| AUUGCUUAAAGU | ||||||||

| RybB | fadLb | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 1-8 | 43-50 | GCCACUGCUUU | 42 |

| |||||||| | ||||||||

| UCACGGUGACGCUG | ||||||||

| RybB | tsxb | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 1-7 | −13-−7 | GCCACUGCUU | 44 |

| ||||||| | ||||||||

| AUACGGUGACAAA | ||||||||

| RybB | ompAb | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 1-8 | 25-32 | GCCACUGCUUU | 42 |

| |||||||| | ||||||||

| UCACGGUGACGUUA | ||||||||

| RybB | ompWb | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 1-7 | 14-20 | GCCACUGCUU | 42 |

| ||||||| | ||||||||

| CGGCGGUGACAAU | ||||||||

| RyhB | cysE | Repression | a, b, f | mRNA probing, | 34-46 | −4-+9 | AAAGCACGACAUUGCUCAC | 55 |

| compensatory mutations | ||||||||||||| | |||||||

| AAGUGUGCUGUAACGAAUG | ||||||||

| RyhB | fur | Repression | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 42-47 | −60-−55 | ACAUUGCUCACA | 73 |

| |||||| | ||||||||

| UUAAACGAGAAC | ||||||||

| RyhB | iscS | Repression | a, b, c, f | mRNA probing | 40-47, 62-68 | −5-+3, −26-−20 | CGACAUUGCUCACAUUGCUUCCAGUAUUACUUAGC | 16 |

| |||||||||||||| | ||||||||

| AAAGUAACGAGATAUUUGAGGCAUGUAGUGAGUUA | ||||||||

| RyhB | shiA | Activation | a, b, d, e | Compensatory mutations | 44-55 | −59-−48 | AUUGCUCACAUUGCUUCC | 47 |

| |||||||||||| | ||||||||

| CAUUGAGUGUAACGGCAG | ||||||||

| RyhB | sodB | Repression | a, b, d, e, g | Compensatory mutations | 38-46 | −4-+5 | CACGACAUUGCUCAC | 1, 38, 68, 72 |

| ||||||||| | ||||||||

| UUACUGUAACGAUGA | ||||||||

| SgrS | ptsG | Repression | a, b, c, d | Compensatory mutations | 168-181 | −22-−9 | CAUGUGUGACUGAGUAUUGG | 28-30, 68, 71 |

| |||||||||||| | ||||||||

| UCUCACGAGGACUCAUACCC | ||||||||

| Spot-42 | galK | Repression | a, c, f, h | sRNA probing | 20-36, 53-61 | −19-−11, +5-+14 | AGAUGUUCUAUCUUUCAGACCUU | 40, 68 |

| ||||| |||||||||| | ||||||||

| AACACAAAAAAGAAAGUCUGAGU | ||||||||

| UAAUCGGAUUUGGCU | ||||||||

| ||||||||| | ||||||||

| UGAGGCCUAAGCGCU |

The evidence types for the regulation are as follows: a, expression or deletion of the sRNA affected the level of the target protein (or a translational fusion). b, Northern blot-based evidence indicated that the expression or deletion of the sRNA affected the level of the target mRNA under specific conditions. c, the sRNA and the target form a stable duplex in vitro. d, mutations in the sRNA affected regulation. e, compensatory mutations in the sRNA and its target recovered the regulation. f, in vitro chemical/enzymatic probing of the sRNA-target complex was performed. g, the sRNA-target duplex is cleaved by RNase III. h, a toe-printing assay showed that the sRNA prevents or allows ribosome binding.

The target was found in a Salmonella sp., but the hybridization is conserved in E. coli.

The upper sequence corresponds to the sRNA oriented 5′→3′ and the lower sequence corresponds to the mRNA oriented 3′→5′.

TABLE 2.

List of targets from small-scale experiments lacking precise determination of the binding region

| sRNA | Target | Regulation | Evidencea | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DicF | ftsZ | Repression | a, b | 64, 65 |

| FnrS | cydD | Repression | b | 10, 18 |

| FnrS | metE | Repression | a, b | 10, 18 |

| FnrS | sodA | Repression | a, b | 10 |

| FnrS | yobA | Repression | a, b | 10, 18 |

| GcvB | cycA | Repression | a, b | 48 |

| GcvB | oppA | Repression | a, b, f, g | 58, 66, 70 |

| MgrR | eptB | Repression | b | 41 |

| MgrR | ygdQ | Repression | b | 41 |

| MicA | ompX | Repression | b | 25 |

| OhsC | shoB | Repression | b | 20 |

| OmrA | fecA | Repression | b | 22 |

| OmrA | fepA | Repression | b | 22 |

| OmrB | fecA | Repression | b | 22 |

| OxyS | rpoS | Repression | a, b, d | 3, 77, 78 |

| RseX | ompA | Repression | b, c | 17 |

| RseX | ompC | Repression | b, c | 17 |

| RybB | ompC | Repression | b | 26 |

| RydC | yejABEF | Repression | b, c | 6 |

| RyhB | acnA | Repression | b | 38 |

| RyhB | bfr | Repression | b | 38 |

| RyhB | ftnA | Repression | b | 38, 43 |

| RyhB | fusmA | Repression | b | 38 |

| RyhB | sdhD | Repression | b | 38, 68 |

For evidence codes, see Table 1, footnote a.

Computing conservation of a sequence region.

The conservation of a region was determined using two different methods. By each method we computed a positional conservation score for each position in the studied region, and the conservation score of the region was the average score over all positions included in it. The first positional conservation measure was based on the conservation track of the UCSC genome browser (57), named PhastCons. The other positional conservation measure was computed based on alignment of the query sRNA with similar sequences that were found using the Smith-Waterman algorithm (62). The entire sequence of the sRNA was submitted to supermatcher of the EMBOSS package (http://emboss.sourceforge.net/) and compared to all 1,193 completed bacterial genome sequences available in the NCBI genome database (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/Bacteria). We defined the substitution matrix used by supermatcher as the default one except for thymine/cytosine or adenine/guanine substitutions, which were scored as 1. The bacteria encoding similar sequences to the sRNA (putative orthologs) were chosen according to the scores supermatcher returned (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). This method detected nearly all orthologs of the sRNA, including only a small number of false positives. By aligning the sequences found to be similar to the E. coli sRNA with the query sequence, the conservation score of position j was defined based on the positional entropy as

|

where p(n) is the frequency of nucleotide n at position j in the alignment of E. coli sRNA and its putative orthologs. A comparison of this positional conservation score and the PhastCons scores is shown in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material. The various sRNAs differ in the number of orthologs, with some being conserved only in very close bacteria and others being conserved throughout more remote bacteria. Using the positional entropy as the basis for the conservation score ensured that regardless of the number of genomes in which orthologs of an sRNA were found, the conservation values of the different sRNAs were comparable.

Computing accessibility of a sequence region.

The RNA accessibility was computed in two different ways. In the first method, the ensemble of the secondary structures of the sRNA was computed using RNAfold −p of the Vienna package (23). The ensemble was then used to calculate the probability of a nucleotide being unpaired by summing up the probabilities of a nucleotide to base pair with any other nucleotide and subtracting this value from 1. These probabilities were averaged along a window. The second method used the program RNAup (42) from the same package, specifying the length of the unpaired region parameter (-u) as the length of the inspected sRNA region. The accessibility score was determined as the energy required to maintain the region unpaired. Since the energy values are not comparable for regions of different lengths, this method was used only for analyses with a fixed window size. A comparison of the two scores is presented in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material.

Variation of accessibility across sRNA orthologs.

For each sRNA the accessibility values were computed by the first method for each putative ortholog in windows corresponding to the windows in E. coli. For corresponding windows along the sRNA, the coefficient of variation of the accessibility values of all orthologs was computed (standard deviation divided by the mean).

Excluding terminator regions.

It is possible that the rho-independent terminators of the various sRNAs, being highly structured and less accessible, may bias the relative accessibility of the target-binding regions. To verify that this is not the case, some of the analyses were repeated after removal of the terminators (determined as the stem-loop structure at the 3′ of the sRNA).

Naïve Bayes classifier.

To test the features that can distinguish target-binding from non-target-binding regions, a naïve Bayes classifier with cross validation was applied. In order to use the classifier, target-binding and non-target-binding windows of a fixed size were determined. One window was assigned to each target-binding region as follows: if the window size was larger than the reported region, additional nucleotides were added to the region from both upstream and downstream when possible. If the window size was smaller than the target-binding region, the central window in the region was chosen. When two target-binding regions were separated by a sequence smaller than or equal to the length of the window, the two were united to one target-binding region. A non-target-binding window was any window without any nucleotide overlapping a target-binding region or a target-binding window. Other windows were not used in this analysis.

The naïve Bayes classifier of MATLAB's Statistics Toolbox (MathWorks) was used to compute the posterior probability of every window of a fixed size in an sRNA to be in the interacting interface with putative mRNA targets. The features used for the classification were average evolutionary conservation of the window, its RNA accessibility, and nucleotide composition. Different combinations of these features were tested. The kernel distribution was used for all features.

Cross validation.

To test the predictive value of the classifier, a leave-one-out cross validation scheme was used. In each iteration, all sRNAs with known binding regions but one were used to train the classifier, and it was tested on the left-out sRNA. The probabilities of the target-binding windows of the left-out sRNA and those of its non-target-binding windows were used to analyze the performance of the classifier. A ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve was plotted using these probabilities. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was used as a measure for comparing different window sizes and feature combinations.

Matches between an sRNA and an mRNA.

To test if an sRNA might bind a target mRNA, a putative base pairing of seven consecutive nucleotides between the sRNA and the 5′ region of the mRNA from nucleotide −80 to nucleotide +20 relative to the translation start site was sought, disallowing G:U base pairing. Any such base pairing was termed a match between the two. A window of a given size on the sRNA containing a heptamer matching at least one target was determined a target-matching window. A window that did not match any target was termed a non-target-matching window.

RESULTS

Database of sRNA target-binding regions.

Since most data on sRNAs and their targets are from E. coli, we focus in this study on E. coli sRNAs. We compiled a database of experimentally verified sRNA-target pairs as described in Materials and Methods. Due to the high similarity between Salmonella and E. coli genomes, we also included reported targets from Salmonella if the hybridization potential between the sRNA and the mRNA was conserved in E. coli. In total, our database included 73 sRNA-mRNA pairs involving 23 sRNAs (Tables 1 and 2; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). All these targets were verified in small-scale experiments, and sRNA-mRNA binding regions were experimentally determined for several of them. We divided the sRNA target-binding regions in these data into two types based on the evidence used for their determination.

(i) Reliable regions (29 regions in 19 sRNAs involving 49 sRNA-mRNA pairs [Table 1]). sRNA target-binding regions were verified using chemical or enzymatic probing, mRNA-sRNA compensatory mutations, or RNase III cleavage. Hereinafter these regions are termed “reliable.” Binding regions for which only the sRNA was mutated were classified as reliable binding regions if several mutations were tested and had the expected influence on the regulation. Some of the target-binding regions were identified more than once (in complexes of the same sRNA with different targets).

(ii) Putative regions based on small-scale experiments (regions in 13 sRNAs involving 24 sRNA-mRNA pairs [Table 2]). Putative sRNA-mRNA binding regions in targets were verified using Northern blotting or assays like translational fusion or in vitro hybridization. Putative binding between the sRNA and mRNA is assumed to exist since the regulation is most probably direct, but there was no direct experimental evidence supporting these regions. These regions were termed “putativeSS,” for putative regions based on Small-Scale experiments.

In addition to the targets found in small-scale experiments, we added probable targets based on high-throughput microarray experiments, which measured the transcriptome change in the presence of an sRNA. We considered targets that were reported as statistically significantly up or downregulated in the experiment, a total of 270 sRNA-mRNA pairs involving nine sRNAs (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). These pairs added additional putative sRNA target-binding regions termed “putativeLS,” for putative regions based on Large-Scale experiments.

The reliable regions were used for characterizing the target-binding regions and training a classifier for predicting such regions, while the putative regions were computationally predicted and used for assessment of the classifier, as described below.

Characterizing sRNA target-binding regions.

A target-binding region of an sRNA is a region that is essential for the regulation of at least one mRNA target. The nucleotides of an sRNA participating in the base pairing with its target were defined as the target-binding region (Table 1 shows the reliable binding regions), while the rest of the sRNA was defined as non-target binding.

(i) Binding region location.

Unlike eukaryotic microRNAs (miRNAs), whose base pairing with target mRNAs is usually mediated through a short seed region of 6 to 8 bases at their 5′ ends (8), the target-binding region of bacterial sRNAs seems to be scattered all along the molecule. Our analysis of the compiled data set revealed five sRNAs that bind their targets through a region at their most 5′ end (RybB, FnrS, MicC, OmrA, and OmrB), while the rest of the target-binding regions were located in various positions along the sRNAs.

(ii) Target-binding region length.

The length of the hybridization between an sRNA and its target was found to be 13 to 24 base pairs. This observation was based only on the nine hybridizations determined by chemical probing, since in our data this was the only method that could provide information about all nucleotides involved in the binding.

(iii) Nucleotide content of target-binding regions.

In general, the nucleotide content of the target-binding regions was not found to be different from those of the rest of the sRNA sequences. In some sRNAs the target-binding region was found to be characterized by specific nucleotides, like G/U in GcvB, or a stretch of six uridine nucleotides in FnrS and DsrA.

(iv) Accessibility of the target-binding regions.

The accessibility of the target-binding regions was compared to the accessibility of non-target-binding regions. For each sRNA the latter included nonoverlapping segments across the sRNA, of the same length as the longest target-binding region of that sRNA. To compare the target-binding and non-target-binding regions, we computed a measure of the accessibility using the RNAfold −p program of the Vienna package (23) (see Materials and Methods). Using this program we computed an accessibility measure for each position, and the accessibility value of a RNA segment was the average of probabilities of all positions contained in it.

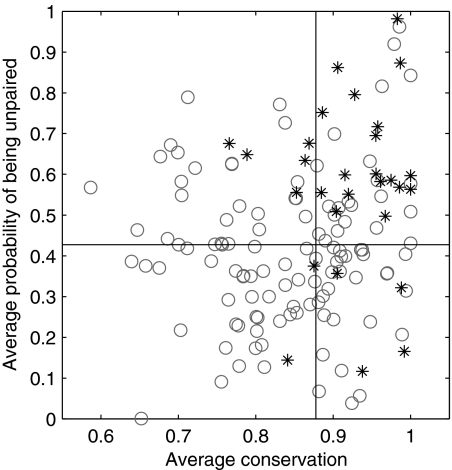

As demonstrated in Fig. 1, the accessibility values of the target-binding regions are higher than those of the non-target-binding ones (P = 10−6 by a Mann-Whitney test). This result was still valid when we omitted the terminators from the analysis. Thus, the target-binding regions are more accessible than the non-target-binding regions. Also, for each sRNA we computed the accessibility of corresponding windows in the orthologous sRNAs. This analysis showed that there is little variation in accessibility, as evident by the low coefficient of variation obtained. The higher the accessibility of the binding region in E. coli, the smaller was the coefficient of variation.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of accessibility and evolutionary conservation between target-binding regions and non-target-binding regions. The evolutionary conservation was computed for each region using the alignment of the different sRNAs with homologous sequences in other bacteria and computing a measure based on the positional entropy (as described in Materials and Methods). Accessibility was derived from the secondary structure ensembles using the RNAfold −p program of the Vienna package (as described in Materials and Methods). Only experimentally determined binding regions were included. The vertical and horizontal lines represent the median of the conservation and accessibility of all the data points in the plot, respectively. It is clearly seen that target-binding regions from all the sRNAs (stars) are more accessible and more evolutionarily conserved than non-target-binding regions (circles). These results are highly statistically significant.

(v) Evolutionary conservation of the binding regions.

We conducted a similar comparison for the conservation values of target-binding versus non-target-binding regions. For this we used two measures. By one measure we used the PhastCons values taken from the UCSC genome browser (57). By the other method, we found putative orthologs of E. coli sRNAs by the Smith-Waterman algorithm (62), aligned them to the E. coli sequence, and computed a conservation score based on entropy computation (as described in Materials and Methods). These results are shown in Fig. 1 (and in Fig. S5 in the supplemental material) for the conservation values computed by the entropy and PhastCons, respectively. In both comparisons we found that the target-binding regions are more evolutionarily conserved than random regions (P = 4 × 10−5 and 0.001 by the Mann-Whitney test for entropy and PhastCons measures, respectively). When the terminators were excluded from the analysis the results remained consistent, although less statistically significant.

Predicting target-binding regions in a small RNA.

The statistically significant differences in the accessibility and conservation measures between target-binding and non-target-binding regions of an sRNA suggest that these properties may be useful for predicting the active regions of an sRNA. Thus, in principle, an sRNA sequence can be screened in overlapping windows of a certain size, the conservation and accessibility measures can be computed for each window, and a predictive algorithm trained on the known sequences is expected to distinguish the windows that fulfill the target-binding region properties from random regions. To develop such an algorithm we used a naïve Bayes classifier, applying a leave-one-out cross validation. The classifier gets computed features of the window as input, assumes their independence, and computes the probability of a window being a target-binding window. This probability is referred to as “posterior probability.” To ensure that the independence assumption is valid, we computed Spearman's rank correlation coefficient between conservation and accessibility in a sequence window. Repeating this analysis for various window sizes revealed statistically significant weak correlations between conservation and accessibility of 0.2 to 0.25.

In our analysis of target-binding region length described above, we found a large variability among the binding regions, ranging in length from 13 to 24 nucleotides (nt). Thus, while it is obvious that a target-binding region of an sRNA should be long enough to allow proper recognition and binding between the sRNA and its target, it is hard to predict what the length of a particular binding region would be. Therefore, we trained the classifier with various window sizes, keeping in each run the window size fixed for all sRNAs in the training and test sets. One window for each target-binding region was tagged as a target-binding window (as described in Materials and Methods), while the rest of the windows that do not overlap target-binding regions were tagged as non-target-binding ones. Since in our data there were 19 sRNAs with reliable target-binding regions, for each window size we ran the classifier 19 times; each time, one sRNA sequence was left out and the classifier was trained on all but this sequence and tested on the left-out sequence.

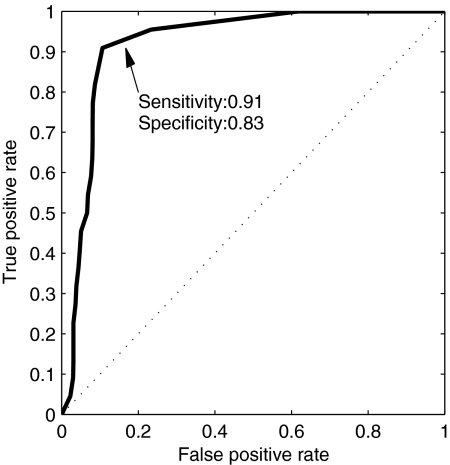

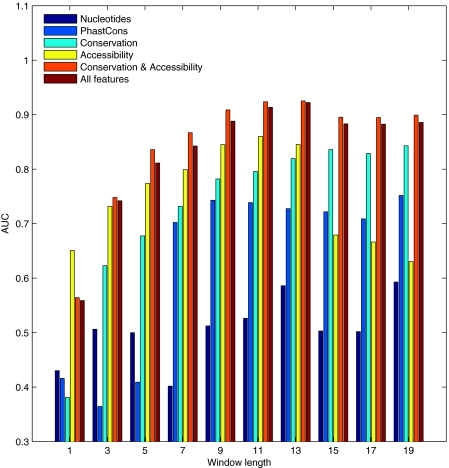

The posterior probabilities returned by the classifier for windows in the left-out sRNAs to be target binding were used to evaluate its specificity and sensitivity and to generate a ROC curve. For generating the ROC curve we determined different thresholds of the posterior probability values above which a window was considered predicted to be target binding. These thresholds determined the true-positive rate (fraction of target-binding windows that had a probability above the threshold) and the false-positive rate (fraction of non-target-binding windows that exceeded this threshold). Such a curve is shown in Fig. 2. We computed the area under the curve (AUC) and used it to compare different predictors, defined by different combinations of features and various window sizes. The window features used were the accessibility and conservation measures (each computed in two different ways) and the nucleotide composition.

FIG. 2.

ROC curve of the naïve Bayes classifier. A leave-one-out cross validation was applied in order to assess the predictive power of the classifier. This ROC curve shows the results of a predictor using a window size of 13 nt, evolutionary conservation computed using the entropy, and region accessibility. Plotted is the true-positive rate against the false-positive rate for different thresholds of the posterior probability, above which a window is considered target binding. Specificity is defined as the fraction of predicted negatives out of all negatives, and sensitivity is defined as the fraction of predicted positives out of all positives. The specificity and sensitivity values marked in the plot are for the threshold of 0.5. The area under the curve is >0.92.

The AUC values of the different predictors with different window sizes and feature combinations are demonstrated in Fig. 3. It is clear that the addition of the nucleotide content did not add to the performance of the classifier and the measures of the accessibility and conservation were sufficient. The highest-scoring AUC was achieved for a window with a length of 13 nt using the evolutionary conservation computed by entropy combined with RNA accessibility computed by either of the two methods used. The AUC was 0.92, and using window posterior probability above 0.5 as a threshold led to the detection of 91% of the target-binding regions with a specificity of 83% (Fig. 2). The posterior probabilities of windows along sRNAs that have targets with a reliable binding region are plotted in Fig. 4, where the overlap between the known-binding regions and high posterior probability values is easily observed. As shown in Fig. 4, the predictor also assigned high posterior probability values to some regions along the sRNA that were not reported to bind a target (e.g., in GcvB). These might be target-binding regions that have not yet been identified experimentally. Posterior probabilities indicative of putative binding regions for other sRNAs, for which a reliable target-binding region has not yet been reported, can be found in Fig. S6 in the supplemental material. The corresponding predicted target-binding regions are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

FIG. 3.

AUC values of different feature combinations and window sizes, measuring the various classifier performances. The features included in the different classifiers include nucleotide content (dark blue), conservation based on PhastCons (light blue), conservation based on entropy (turquoise), accessibility computed using ensemble (yellow), combination of conservation by entropy and accessibility by ensemble (orange), and combination of nucleotide content, conservation by entropy, and accessibility by ensemble (brown). The highest AUC value was achieved using conservation computed using the entropy and accessibility in a window of 13 nt.

FIG. 4.

Posterior probabilities of being a target-binding region, computed by the classifier, are higher for the real target-binding regions than for non-target-binding regions. The probability provided by the classifier appears as a solid line, while the conservation and the accessibility are shown as dashed and dotted lines, respectively. The shaded areas are the non-target-binding regions, and the light ones are target-binding regions. The x axis represents the positions along the sRNA (in nucleotides). Values on the y axis correspond to the posterior probability, conservation score, and probability of being unpaired for the solid, dashed, and dotted lines, respectively.

Small RNAs target mRNAs using their predicted regions.

We next turned to demonstrating that identifying the target-binding regions of small RNAs by the classifier is valuable for predicting targets of small RNAs. To this end, we used the other target-binding regions in our data, putativeSS and putativeLS. These target-binding regions were not experimentally identified, but they are included in sRNAs that were shown experimentally to target specific mRNAs (putativeSS by small-scale experiments and putativeLS by large-scale experiments). We determined the putative binding regions of these sRNA-mRNA pairs by identifying base pairing of seven consecutive nucleotides between the sRNA and the 5′ region of its target mRNA. This simple criterion was based on the premise that almost all experimentally determined binding regions show such consecutive base pairing, and the probability of obtaining such a base pairing by chance is low. Pairs of sRNA-target for which such a match could not be identified were excluded from the analysis.

We then ran the classifier on these sRNA sequences. For each sRNA sequence we computed the posterior probabilities of windows overlapping putative target-binding regions and recorded the one with maximal posterior probability. As a control, we applied the same procedure to a negative set based on data from the sRNATarBase database (12). This set comprised pairs of sRNAs and mRNAs for which it was shown experimentally that the sRNA had no effect on the mRNA. Only pairs of sRNA-mRNA that had a match of seven consecutive base pairs were used for the evaluation. As shown in Fig. 5, the windows corresponding to putative target-binding regions of the experimentally determined targets had statistically significantly higher posterior probabilities than those of the control group (P = 0.001 and 3 × 10−7 for the putativeLS and putativeSS groups, respectively, by the Mann-Whitney test). This observation points out the importance of indicating the active regions of an sRNA as an important step in predicting its targets. Since a match between an sRNA and an mRNA is usually found (in 60% of the sRNA-mRNA pairs in the negative set), it is beneficial to narrow down the search space to highly probable sRNA active regions in order to filter false predictions without missing too many true targets.

FIG. 5.

Distribution of the maximal probabilities obtained by the classifier for sRNA-mRNA pairs with putative target-binding regions. Included are putative binding regions of sRNA-mRNA pairs from small-scale (putativeSS, white) and large-scale (putativeLS, gray) experiments and regions in sRNA-mRNA pairs shown experimentally not to bind (black). For each sRNA-mRNA pair, matching windows were determined and their probability of being in a target-binding region was computed by the classifier. For each target, the target-matching window with the highest probability was chosen. The distributions of the putative regions of experimentally determined target groups differ statistically significantly from those of nontargets (P = 0.001 and 3 × 10−7 for the putativeLS and putativeSS groups, respectively; Mann-Whitney test).

DISCUSSION

Although bacterial sRNAs were discovered and studied long before miRNAs, the latter underwent many more systematic characterizations than the former. The analysis of target-binding regions of bacterial sRNAs reported here enables us to compare the two groups. Unlike miRNAs, for which it was found that a short region of 6 to 8 nucleotides at the 5′ end (“seed” region) is involved in binding most mRNA targets (reviewed in reference 8), the target-binding regions of bacterial sRNAs seem to be positioned in different locations along the molecule, and their lengths vary between 13 and 24 nt. Still, it was recently shown for the target-binding region at the 5′ end of RybB that it carries the regulatory function of RybB by itself and can bring about the same regulatory effect when fused to other sequences (44). This suggests that sRNAs do have active regions that are responsible for base pairing with their targets, and they can do so without the context of the rest of the molecule. This short sequence is sometimes referred to as the “seed” of the sRNA (44). Similarly to miRNAs, the target-binding regions of sRNAs are highly evolutionarily conserved, often constituting the most conserved regions of the molecule. Another property, relevant to sRNAs but not to miRNAs, is the accessibility of the target-binding region. Since the mature miRNA is very short (∼22 nt) it is generally regarded as a linear stretch of nucleotides base pairing with the mRNA. Therefore, for most miRNAs the seed region is considered embedded in a surface-accessible structure. The sRNA, on the other hand, ranges in size between 50 and 400 nt and folds into secondary and tertiary structures, and its target-binding region might be located in different positions along this structure. It is conceivable that an accessible target-binding region should be preferred energetically, and therefore it was intriguing to examine whether the known binding regions are indeed preferentially located in accessible regions. This assessment was based on free energy computations applied to the sRNA and did not take into account proteins, such as Hfq, which might play a role in exposing the target-binding region. Such effects were not yet quantified energetically and could not be incorporated. By this computation we showed that the target-binding regions are more accessible than random regions and in many cases are located in the most accessible region of the sRNA (Fig. 4). Thus, our systematic analysis confirmed and further supported two properties of the sRNA target-binding regions that were conjectured before, based on sporadic cases: their surface accessibility and their evolutionary conservation.

The measures of accessibility and evolutionary conservation differed statistically significantly between known binding regions and random regions of the same size along the sRNA, suggesting that they can be used for prediction of sRNA target-binding regions. We used the reliable target-binding regions in our data to train a predictive algorithm with cross validation, incorporating these two features alone or in combination with others, and using different window sizes to screen the sequences. Indeed, we found that using only the surface accessibility and evolutionary conservation is sufficient for successfully identifying the target-binding regions.

Using accessibility or conservation separately resulted in a predictor that was less powerful than a predictor based on both measures. Although the conservation and accessibility measures are somewhat correlated, combining the two types of evidence has an advantage over using either of them. This can be observed in Fig. 1 by looking at the regions with accessibility values higher than the median value. The target-binding regions and the non-target-binding regions above this line can be nicely separated by conservation but not by accessibility. These observations suggest that conservation and accessibility are not redundant in predicting sRNAs’ active regions.

Using the nucleotide composition as a predictor, by itself or in combination with conservation and accessibility, had no predictive value. This result might suggest that the accessible regions along sRNAs are accessible not because of their low G+C content but because of their inability to pair with the rest of the molecule. Also, since the best results were obtained for a window of 13 nt, it might be hypothesized that the minimal region required for the targeting of an mRNA by an sRNA requires the hybridization of about 13 nt, consistent with the minimal length of interaction detected using probing.

The cross validation indicated that the predictor can successfully identify the experimentally determined target-binding regions. For other targets, identified in either small-scale or large-scale experiments, we determined the target-binding regions computationally by searching matching regions between the sRNA and its target mRNAs. It is therefore satisfying that these target-matching windows reside in regions predicted by the classifier to be target binding. This implies that determination of target-binding regions on small RNAs is valuable also for target prediction, as its incorporation in target prediction algorithms is expected to reduce the number of false positives while hardly missing true positives. Thus, our identification of the target-binding regions of sRNAs by their higher accessibility and evolutionary conservation is useful for narrowing down the list of putative targets of an sRNA, a long-standing goal in the field.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 January 2011.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afonyushkin, T., B. Vecerek, I. Moll, U. Blasi, and V. R. Kaberdin. 2005. Both RNase E and RNase III control the stability of sodB mRNA upon translational inhibition by the small regulatory RNA RyhB. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:1678-1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiba, H., S. Matsuyama, T. Mizuno, and S. Mizushima. 1987. Function of micF as an antisense RNA in osmoregulatory expression of the ompF gene in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169:3007-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altuvia, S., D. Weinstein-Fischer, A. Zhang, L. Postow, and G. Storz. 1997. A small, stable RNA induced by oxidative stress: role as a pleiotropic regulator and antimutator. Cell 90:43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altuvia, S., A. Zhang, L. Argaman, A. Tiwari, and G. Storz. 1998. The Escherichia coli OxyS regulatory RNA represses fhlA translation by blocking ribosome binding. EMBO J. 17:6069-6075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen, J., and N. Delihas. 1990. micF RNA binds to the 5′ end of ompF mRNA and to a protein from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 29:9249-9256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antal, M., V. Bordeau, V. Douchin, and B. Felden. 2005. A small bacterial RNA regulates a putative ABC transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 280:7901-7908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Argaman, L., and S. Altuvia. 2000. fhlA repression by OxyS RNA: kissing complex formation at two sites results in a stable antisense-target RNA complex. J. Mol. Biol. 300:1101-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartel, D. P. 2009. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136:215-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bossi, L., and N. Figueroa-Bossi. 2007. A small RNA downregulates LamB maltoporin in Salmonella. Mol. Microbiol. 65:799-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boysen, A., J. Moller-Jensen, B. Kallipolitis, P. Valentin-Hansen, and M. Overgaard. 2010. Translational regulation of gene expression by an anaerobically induced small non-coding RNA in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 285:10690-10702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busch, A., A. S. Richter, and R. Backofen. 2008. IntaRNA: efficient prediction of bacterial sRNA targets incorporating target site accessibility and seed regions. Bioinformatics 24:2849-2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao, Y., et al. 2010. sRNATarBase: a comprehensive database of bacterial sRNA targets verified by experiments. RNA 16:2051-2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, S., A. Zhang, L. B. Blyn, and G. Storz. 2004. MicC, a second small-RNA regulator of Omp protein expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:6689-6697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coornaert, A., et al. 2010. MicA sRNA links the PhoP regulon to cell envelope stress. Mol. Microbiol. 76:467-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Lay, N., and S. Gottesman. 2009. The Crp-activated small noncoding regulatory RNA CyaR (RyeE) links nutritional status to group behavior. J. Bacteriol. 191:461-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desnoyers, G., A. Morissette, K. Prevost, and E. Masse. 2009. Small RNA-induced differential degradation of the polycistronic mRNA iscRSUA. EMBO J. 28:1551-1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Douchin, V., C. Bohn, and P. Bouloc. 2006. Down-regulation of porins by a small RNA bypasses the essentiality of the regulated intramembrane proteolysis protease RseP in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 281:12253-12259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durand, S., and G. Storz. 2010. Reprogramming of anaerobic metabolism by the FnrS small RNA. Mol. Microbiol. 75:1215-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Figueroa-Bossi, N., M. Valentini, L. Malleret, F. Fiorini, and L. Bossi. 2009. Caught at its own game: regulatory small RNA inactivated by an inducible transcript mimicking its target. Genes Dev. 23:2004-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fozo, E. M., et al. 2008. Repression of small toxic protein synthesis by the Sib and OhsC small RNAs. Mol. Microbiol. 70:1076-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guillier, M., and S. Gottesman. 2008. The 5′ end of two redundant sRNAs is involved in the regulation of multiple targets, including their own regulator. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:6781-6794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guillier, M., and S. Gottesman. 2006. Remodelling of the Escherichia coli outer membrane by two small regulatory RNAs. Mol. Microbiol. 59:231-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofacker, I., W. Fontana, S. Bonhoeffer, and P. Stadler. 1994. Fast folding and comparison of RNA secondary structures. Monatsh. Chem. 125:167-188. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmqvist, E., et al. 2010. Two antisense RNAs target the transcriptional regulator CsgD to inhibit curli synthesis. EMBO J. 29:1840-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johansen, J., M. Eriksen, B. Kallipolitis, and P. Valentin-Hansen. 2008. Down-regulation of outer membrane proteins by noncoding RNAs: unraveling the cAMP-CRP- and sigmaE-dependent CyaR-ompX regulatory case. J. Mol. Biol. 383:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansen, J., A. A. Rasmussen, M. Overgaard, and P. Valentin-Hansen. 2006. Conserved small non-coding RNAs that belong to the sigmaE regulon: role in down-regulation of outer membrane proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 364:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jousselin, A., L. Metzinger, and B. Felden. 2009. On the facultative requirement of the bacterial RNA chaperone, Hfq. Trends Microbiol. 17:399-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawamoto, H., Y. Koide, T. Morita, and H. Aiba. 2006. Base-pairing requirement for RNA silencing by a bacterial small RNA and acceleration of duplex formation by Hfq. Mol. Microbiol. 61:1013-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawamoto, H., T. Morita, A. Shimizu, T. Inada, and H. Aiba. 2005. Implication of membrane localization of target mRNA in the action of a small RNA: mechanism of post-transcriptional regulation of glucose transporter in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 19:328-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimata, K., Y. Tanaka, T. Inada, and H. Aiba. 2001. Expression of the glucose transporter gene, ptsG, is regulated at the mRNA degradation step in response to glycolytic flux in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 20:3587-3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lease, R. A., M. E. Cusick, and M. Belfort. 1998. Riboregulation in Escherichia coli: DsrA RNA acts by RNA:RNA interactions at multiple loci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:12456-12461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majdalani, N., S. Chen, J. Murrow, K. St John, and S. Gottesman. 2001. Regulation of RpoS by a novel small RNA: the characterization of RprA. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1382-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Majdalani, N., C. Cunning, D. Sledjeski, T. Elliott, and S. Gottesman. 1998. DsrA RNA regulates translation of RpoS message by an anti-antisense mechanism, independent of its action as an antisilencer of transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:12462-12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majdalani, N., D. Hernandez, and S. Gottesman. 2002. Regulation and mode of action of the second small RNA activator of RpoS translation, RprA. Mol. Microbiol. 46:813-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandin, P., and S. Gottesman. 2009. A genetic approach for finding small RNAs regulators of genes of interest identifies RybC as regulating the DpiA/DpiB two-component system. Mol. Microbiol. 72:551-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandin, P., and S. Gottesman. 2010. Integrating anaerobic/aerobic sensing and the general stress response through the ArcZ small RNA. EMBO J. 29:3094-3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mandin, P., F. Repoila, M. Vergassola, T. Geissmann, and P. Cossart. 2007. Identification of new noncoding RNAs in Listeria monocytogenes and prediction of mRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:962-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masse, E., and S. Gottesman. 2002. A small RNA regulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:4620-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizuno, T., M. Y. Chou, and M. Inouye. 1984. A unique mechanism regulating gene expression: translational inhibition by a complementary RNA transcript (micRNA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 81:1966-1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moller, T., T. Franch, C. Udesen, K. Gerdes, and P. Valentin-Hansen. 2002. Spot 42 RNA mediates discoordinate expression of the E. coli galactose operon. Genes Dev. 16:1696-1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moon, K., and S. Gottesman. 2009. A PhoQ/P-regulated small RNA regulates sensitivity of Escherichia coli to antimicrobial peptides. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1314-1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muckstein, U., et al. 2006. Thermodynamics of RNA-RNA binding. Bioinformatics 22:1177-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nandal, A., et al. 2010. Induction of the ferritin gene (ftnA) of Escherichia coli by Fe(2+)-Fur is mediated by reversal of H-NS silencing and is RyhB independent. Mol. Microbiol. 75:637-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papenfort, K., M. Bouvier, F. Mika, C. M. Sharma, and J. Vogel. 2010. Evidence for an autonomous 5′ target recognition domain in an Hfq-associated small RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:20435-20440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Papenfort, K., et al. 2008. Systematic deletion of Salmonella small RNA genes identifies CyaR, a conserved CRP-dependent riboregulator of OmpX synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 68:890-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papenfort, K., et al. 2009. Specific and pleiotropic patterns of mRNA regulation by ArcZ, a conserved, Hfq-dependent small RNA. Mol. Microbiol. 74:139-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prevost, K., et al. 2007. The small RNA RyhB activates the translation of shiA mRNA encoding a permease of shikimate, a compound involved in siderophore synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1260-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pulvermacher, S. C., L. T. Stauffer, and G. V. Stauffer. 2009. Role of the sRNA GcvB in regulation of cycA in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 155:106-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pulvermacher, S. C., L. T. Stauffer, and G. V. Stauffer. 2009. The small RNA GcvB regulates sstT mRNA expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 191:238-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramani, N., M. Hedeshian, and M. Freundlich. 1994. micF antisense RNA has a major role in osmoregulation of OmpF in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176:5005-5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rasmussen, A. A., et al. 2005. Regulation of ompA mRNA stability: the role of a small regulatory RNA in growth phase-dependent control. Mol. Microbiol. 58:1421-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rasmussen, A. A., et al. 2009. A conserved small RNA promotes silencing of the outer membrane protein YbfM. Mol. Microbiol. 72:566-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reichenbach, B., A. Maes, F. Kalamorz, E. Hajnsdorf, and B. Gorke. 2008. The small RNA GlmY acts upstream of the sRNA GlmZ in the activation of glmS expression and is subject to regulation by polyadenylation in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:2570-2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Resch, A., et al. 2008. Translational activation by the noncoding RNA DsrA involves alternative RNase III processing in the rpoS 5′-leader. RNA 14:454-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salvail, H., et al. 2010. A small RNA promotes siderophore production through transcriptional and metabolic remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:15223-15228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmidt, M., P. Zheng, and N. Delihas. 1995. Secondary structures of Escherichia coli antisense micF RNA, the 5′-end of the target ompF mRNA, and the RNA/RNA duplex. Biochemistry 34:3621-3631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schneider, K. L., K. S. Pollard, R. Baertsch, A. Pohl, and T. M. Lowe. 2006. The UCSC Archaeal Genome Browser. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:D407-D410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharma, C. M., F. Darfeuille, T. H. Plantinga, and J. Vogel. 2007. A small RNA regulates multiple ABC transporter mRNAs by targeting C/A-rich elements inside and upstream of ribosome-binding sites. Genes Dev. 21:2804-2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shimoni, Y., et al. 2007. Regulation of gene expression by small non-coding RNAs: a quantitative view. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sledjeski, D., and S. Gottesman. 1995. A small RNA acts as an antisilencer of the H-NS-silenced rcsA gene of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:2003-2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sledjeski, D. D., A. Gupta, and S. Gottesman. 1996. The small RNA, DsrA, is essential for the low temperature expression of RpoS during exponential growth in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 15:3993-4000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith, T. F., and M. S. Waterman. 1981. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 147:195-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Storz, G., J. A. Opdyke, and A. Zhang. 2004. Controlling mRNA stability and translation with small, noncoding RNAs. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:140-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tetart, F., R. Albigot, A. Conter, E. Mulder, and J. P. Bouche. 1992. Involvement of FtsZ in coupling of nucleoid separation with septation. Mol. Microbiol. 6:621-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tetart, F., and J. P. Bouche. 1992. Regulation of the expression of the cell-cycle gene ftsZ by DicF antisense RNA. Division does not require a fixed number of FtsZ molecules. Mol. Microbiol. 6:615-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tjaden, B., et al. 2006. Target prediction for small, noncoding RNAs in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:2791-2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Udekwu, K. I., et al. 2005. Hfq-dependent regulation of OmpA synthesis is mediated by an antisense RNA. Genes Dev. 19:2355-2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Urban, J. H., and J. Vogel. 2007. Translational control and target recognition by Escherichia coli small RNAs in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:1018-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Urban, J. H., and J. Vogel. 2008. Two seemingly homologous noncoding RNAs act hierarchically to activate glmS mRNA translation. PLoS Biol. 6:e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Urbanowski, M. L., L. T. Stauffer, and G. V. Stauffer. 2000. The gcvB gene encodes a small untranslated RNA involved in expression of the dipeptide and oligopeptide transport systems in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 37:856-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vanderpool, C. K., and S. Gottesman. 2004. Involvement of a novel transcriptional activator and small RNA in post-transcriptional regulation of the glucose phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1076-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vecerek, B., I. Moll, T. Afonyushkin, V. Kaberdin, and U. Blasi. 2003. Interaction of the RNA chaperone Hfq with mRNAs: direct and indirect roles of Hfq in iron metabolism of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 50:897-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vecerek, B., I. Moll, and U. Blasi. 2007. Control of Fur synthesis by the non-coding RNA RyhB and iron-responsive decoding. EMBO J. 26:965-975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vogel, J., L. Argaman, E. G. Wagner, and S. Altuvia. 2004. The small RNA IstR inhibits synthesis of an SOS-induced toxic peptide. Curr. Biol. 14:2271-2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wadler, C. S., and C. K. Vanderpool. 2007. A dual function for a bacterial small RNA: SgrS performs base pairing-dependent regulation and encodes a functional polypeptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:20454-20459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Waters, L. S., and G. Storz. 2009. Regulatory RNAs in bacteria. Cell 136:615-628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang, A., S. Altuvia, and G. Storz. 1997. The novel oxyS RNA regulates expression of the sigma s subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1997:27-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang, A., et al. 1998. The OxyS regulatory RNA represses rpoS translation and binds the Hfq (HF-I) protein. EMBO J. 17:6061-6068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang, Y., et al. 2006. Identifying Hfq-binding small RNA targets in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 343:950-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao, Y., et al. 2008. Construction of two mathematical models for prediction of bacterial sRNA targets. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 372:346-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.