Abstract

VRE isolates from pigs (n = 29) and healthy persons (n = 12) recovered during wide surveillance studies performed in Portugal, Denmark, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States (1995 to 2008) were compared with outbreak/prevalent VRE clinical strains (n = 190; 23 countries; 1986 to 2009). Thirty clonally related Enterococcus faecium clonal complex 5 (CC5) isolates (17 sequence type 6 [ST6], 6 ST5, 5 ST185, 1 ST147, and 1 ST493) were obtained from feces of swine and healthy humans. This collection included isolates widespread among pigs of European Union (EU) countries since the mid-1990s. Each ST comprised isolates showing similar pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns (≤6 bands difference; >82% similarity). Some CC5 PFGE subtype strains from swine were indistinguishable from hospital vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) causing infections. A truncated variant of Tn1546 (encoding resistance to vancomycin) and tcrB (coding for resistance to copper) were consistently located on 150- to 190-kb plasmids (reppLG1). E. faecium CC17 (ST132) isolates from pig manure and two clinical samples showed identical PFGE profiles and contained a 60-kb mosaic plasmid (repInc18 plus reppRUM) carrying diverse Tn1546-IS1216 variants. The only Enterococcus faecalis isolate obtained from pigs (CC2-ST6) corresponded to a multidrug-resistant clone widely disseminated in hospitals in Italy, Portugal, and Spain, and both animal and human isolates harbored an indistinguishable 100-kb mosaic plasmid (reppRE25 plus reppCF10) containing the whole Tn1546 backbone. The results indicate a current intra- and international spread of E. faecium and E. faecalis clones and their plasmids among swine and humans.

INTRODUCTION

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) are among the most common nosocomial pathogens in the United States and in several European Union (EU) countries (23, 50). They have frequently been isolated from farm animals, pets, and retail food products in Europe, but until very recently, the detection of VRE from either processing or production food animal environments in the United States was infrequent (11, 20, 42, 53). There is limited evidence as to the direct role of the food chain in the dissemination of VRE among humans. Despite this, the potential hazard has been widely recognized and led to the adoption of intervention measures, such as the ban on the growth-promoting use of antimicrobials in the EU. A remarkable reduction in the prevalence of VRE among animals and humans has been observed after the EU withdrawal (see reference 42 and references therein). However, the role of nonhuman hosts as reservoirs of highly transmissible clones, the transient or permanent human fecal carriage of VRE of animal origin, and the consequent risk of gene transfer to resident human flora are issues still discussed and not fully addressed (41, 42).

Both Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis are opportunistic pathogens comprising some host-specific lineages (30, 53). Strains from human-adapted clonal complexes (CCs) causing most enterococcal infections may eventually be recovered from farm and companion animals (e.g., E. faecium clonal complex 17 [CC17] and E. faecalis CC2), and strains from CCs commonly found among animals have also been isolated from humans (E. faecium CC5, E. faecalis sequence type 16 [ST16], or E. faecalis CC21) (4, 9, 13, 14, 28, 53). Documented cases of animal-human VRE transmission frequently involve healthy humans in close interaction (farming or petting) with animals, but most of these studies do not provide molecular characterization of either clones or their subcellular genetic elements (1, 3, 10, 17, 26, 28, 31, 33), despite the comprehensive epidemiological studies of Tn1546 (vanA) and Tn5382 (vanB) (8, 24, 38, 52, 54).

In this work, a comparative multilayered molecular analysis of representative VRE strains from swine, healthy humans, and clinical isolates recovered from wide surveillance studies was carried out with the aim of identifying and characterizing epidemic VRE clones and plasmids shared by human and swine hosts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and epidemiological background.

The epidemiological background of the 41 isolates analyzed in this study is shown in Table 1. It includes representative isolates of VRE recovered from swine and healthy humans in national surveillance studies conducted in Portugal and Denmark (1995 to 2008) (references 17, 26, 35, 37, and 38 and this study), strains widespread among swine from Switzerland and Spain (5, 22), and the first VRE isolates recently recovered from animals in the United States (11). For comparison, we included a large and well-typed collection of clinical VRE isolates (140 E. faecium and 50 E. faecalis isolates) recovered from 23 countries, including Portugal, Spain, Denmark, and the United States, during the last 3 decades, most of which had caused hospital outbreaks (12, 16). Testing of susceptibility to 12 antibiotics was performed either by E strip (bioMérieux, Solna, Sweden) or by a standard agar dilution method following recommended guidelines of the manufacturer or CLSI (6). The presence of genes coding for antimicrobial (glycopeptides, macrolides, tetracyclines, and aminoglycosides) and copper (tcrB) resistance and putative virulence traits (agg, gel, cyl, esp, and hylEfm) was analyzed by using different PCR schemes (18, 36).

Table 1.

Origins of VRE isolated from swine and healthy humans during national surveillance studies in Denmark, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States (1995 to 2008)

| Species | Country | No. isolated from: |

Origin | Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swine | Healthy humans | ||||

| E. faecium (n = 40) | Denmark | 15 | 3 | 15 VREfm from healthy pigs among 1,594 E. faecium fecal isolates (DANMAPa, 1995–2006) | 17, 26; this study |

| 3 VREfm recovered from 525 community-dwelling human samples (2002–2006) | 17; this study | ||||

| Portugal | 4 | 9 | 4 VREfm from 84 fecal or environmental samples in different production piggeries (1997; 2006–2007); one isolate from 1997 belongs to the CC5 widespread clone recovered in different countries over years | 14, 35 | |

| 9 VREfm fecal isolates from 99 healthy volunteers living in different Portuguese cities (2001–2004) | 37 | ||||

| United States | 6 | 0 | 6 VREfm recently isolated from 55 swine (10.9%) in three Michigan counties (2008) | 11 | |

| Spain | 2 | 0 | 2 VREfm recovered from 900 pig fecal samples at slaughterhouses (9.7% of all pigs slaughtered in 1998) in Valencia and Murcia (1998–2000) | 22, 35 | |

| Switzerland | 1 | 0 | 1 VREfm recovered from samples of pig feces among 155 Enterococcus isolates obtained in 16 Swiss farms (1999–2000) | 5, 35 | |

| E. faecalis (n = 1) | Portugal | 1 | 0 | 1 VREfs from 84 fecal or environmental samples in different production piggeries (2006–2007) | 13 |

DANMAP, Danish Integrated Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring and Research Programme.

Clonal relatedness.

Clonal relatedness was established by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and multilocus sequence typing (MLST), as described previously (36, 48; http://www.mlst.net). Computer analysis of the PFGE banding patterns was performed with the Fingerprinting II Informatix software package (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The similarity of the PFGE banding patterns was analyzed by the Dice coefficient, and cluster analysis was performed by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic average (UPGMA). We applied a cutoff equivalent to 82% to group possibly genetically related isolates (34). Different PFGE types were designated by capital letters or numbers (35, 36, 38). Subtypes were designated by a number (indicating the number of bands that differed from the index strain) and primes when necessary (to distinguish among subtypes with the same number of bands but showing different banding patterns) (48).

Characterization of glycopeptide resistance.

The Tn1546 backbone was analyzed by PCR mapping, as previously described (38, 54). Conjugation experiments were performed by filter mating at a 1:1 donor-recipient ratio using E. faecium GE-1 and/or 64/3 and E. faecalis JH2-2 as recipient strains and vancomycin (6 mg/liter), rifampin (30 mg/liter), and fusidic acid (20 mg/liter) as antimicrobial selective markers. The genomic locations of vanA and tcrB were assessed by hybridization of I-CeuI and S1 nuclease (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan)-digested genomic DNA using intragenic vanA, tcrB, and 23S rRNA gene probes (16). Plasmid analysis included determination of size and content by PFGE of S1 nuclease-digested genomic DNA as previously described (16). Also, the identification of replication initiator proteins (rep) and maintenance systems (the toxin-antitoxin systems Axe-Txe and ω-ε-ζ and the partition module parpAD1) was performed using recently developed PCR plasmid-typing methods, sequencing, and hybridization (25, 44). Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis using EcoRI or ClaI enzyme was performed for plasmids of <150 kb (13). The plasmids were designated with Roman numerals (E. faecalis) or capital letters (E. faecium), following the nomenclature of previous studies in which some of the strains were initially reported (13). Hybridization experiments were performed by using the Gene Images AlkPhos Direct labeling and detection system (Amersham GB, GE Healthcare Life Sciences UK Limited). We referred to the rep sequences according to the plasmid type in which they were identified, as well by as the numeric nomenclature used by Jensen et al. (25).

RESULTS

Thirty-two (31 E. faecium [VREfm]; 1 E. faecalis [VREfs]) of the 41 VRE isolates studied were grouped in PFGE types highly similar to those of strains causing infection in hospitalized patients. They were identified as E. faecium CC5 (n = 30), E. faecium CC17 (n = 1), and E. faecalis CC2 (n = 1). Five other fecal isolates from healthy humans were classified as E. faecium ST18 (CC17), which is one of the predominant STs of the polyclonal subcluster CC17, although no similar PFGE types were observed among hospital VRE. The other four isolates were recovered from healthy humans, but their PFGE or MLST profiles were not related to animal or hospital VRE. A detailed analysis of the isolates found in swine and healthy and hospitalized humans is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Epidemiological and genetic backgrounds of clonally related enterococcal isolates from humans and swine recovered in Denmark, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States

| Species and CC | ST | PFGE type | No. of isolates | Source | Country | Yr of isolation | Antibiotic resistance profileg | Antibiotic resistance genes | tcrBh | Putative virulence traits | Tn1546 typef | Matingh |

vanA plasmid |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (kb) | RFLPi | |||||||||||||

| E. faecalis CC2 | ST6 | B3′ | 1 | Hospitalized patient (blood) | Italy | 1993 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY, CIP, GEN, CHL | vanA, tetM, ermB, aac(6′)-aph(2″) | − | agg, gel | A | + | 100 | VI |

| Ba | 1 | Hospitalized patient (blood) | Portugal | 1996 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY, CIP, GEN, KAN, CHL | vanA, tetM, ermB, aac(6′)-aph(2″) | − | agg, gel, cyl, esp | PP-4 | + | 85 | I | ||

| B5 | 1 | Hospitalized patient (blood) | Spain | 1999 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY, CIP, GEN, CHL | vanA, tetM, ermB, aac(6′)-aph(2″) | − | agg, gel | A | + | 100 | III | ||

| B5 | 1 | Piggery (manure) | Portugal | 2007 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY, CIP, GEN, KAN, CHL | vanA, tetM, aac(6′)-aph(2″), aph(3′)-IIIa | − | agg, gel | A | + | 100 | III | ||

| E. faecium CC17 | ST132b | 119c | 2 | Hospitalized patient (UTIj) | Portugal | 2002 | VAN, TEC, AMP, ERY, CIP, GEN, KAN, Q-D | vanA, ermB, aac(6′)-aph(2″), aph(3′)-IIIa | − | esp | PP-13 | + | 65 | P |

| 119.5 | 1 | Piggery (manure) | Portugal | 2007 | VAN, TEC, AMP, ERY, GEN, KAN | vanA, aac(6′)-aph(2″), aph(3′)-IIIa | − | esp | PP-31 | − | 60 | P1 | ||

| E. faecium CC5 | ST5 | A3″″d | 2 | Hospitalized patient (UTI) | Portugal | 2001–2002 | VC, TEC, TET, ERY | vanA, tetM, ermB | + | D | + | 150 | ND | |

| A1″″, A3″, A3″′ | 4 | Slaughterhouse (feces) | Denmark | 2003–2006 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY | vanA, tetM, ermB | + | D (n = 2) | + | 150–170 | ND | |||

| A5 | 2 | Piggery (animal feces) | United States | 2008 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY | vanA, tetM, ermB | + | D | + | 170 | ND | |||

| ST6 | A, A1′, A1″, A2 | 9 | Slaughterhouse (feces) | Denmark | 1995–2006 | VAN, TEC, TET, (ERY) | vanA, tetM, (ermB) | + | D (n = 3) | + | 145–180 | ND | ||

| A | 1 | Healthy humans | Denmark | 2005 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY | vanA, tetM, ermB | + | D | + | 175 | ND | |||

| Ae | 1 | Slaughterhouse (feces) | Portugal | 1997 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY | vanA, tetM, ermB | + | D | + | 175 | ND | |||

| A1 | 1 | Piggery (feces) | Switzerland | 1999 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY | vanA, tetM, ermB | + | D | + | 150 | ND | |||

| A1′ | 2 | Slaughterhouse (feces) | Spain | 1998–2000 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY, KAN, STR | vanA, tetM, ermB, aph(3′)-IIIa | + | D | + | 150 | ND | |||

| A, A1″′ | 3 | Piggery (animal feces) | United States | 2008 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY | vanA, tetM, ermB | + | D (n = 2) | + | 170 | ND | |||

| ST147 | A5 | 1 | Healthy humans | Denmark | 2003 | VAN, TEC, TET | vanA, tetM | + | D | + | 175 | ND | ||

| ST185 | A3, A4′ | 2 | Slaughterhouse (feces) | Denmark | 2001–2004 | VAN, TEC, TET, (ERY) | vanA, tetM, (ermB) | + | D | + | 160–180 | ND | ||

| A3′ | 2 | Piggery (soil) | Portugal | 2007 | VAN, TEC, TET | van, tetM | + | D | + | 150 | ND | |||

| A4 | 1 | Piggery (animal feces) | United States | 2008 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY | vanA, tetM, ermB | + | D | + | 170 | ND | |||

| ST493 | A6 | 1 | Healthy humans | Denmark | 2005 | VAN, TEC, TET, ERY, KAN | vanA, tetM, ermB, aph(3′)-IIIa | + | D | + | 190 | ND | ||

Representative isolate from a hospital outbreak strain widespread in six Portuguese hospitals in different cities (1996–2008).

ST132 is a single-locus variant of ST18.

Representative strain of two isolates causing single urinary tract infections in unrelated patients in one Porto hospital during 2002; only one was characterized.

Clinical strain causing single urinary tract infections and disseminated in two hospitals during 2001–2002.

Representative isolates of a strain widespread in Europe since the mid-1990s (35).

The Tn1546 designation is based on PCR mapping as described previously (38, 54). Briefly, type A corresponds to the whole Tn1546 backbone; type D contains alterations within orf1 and a point mutation at position 8234 in vanX; PP-4 contains an ISEf1 insertion within the vanX-vanY region; PP-13 and PP-31 have an IS1216 insertion within the vanX-vanY region (PP-31 differs in the region upstream of vanR). The number of isolates included in the Tn1546 typing is indicated when appropriate.

VAN, vancomycin; TEC, teicoplanin; AMP, ampicillin; TET, tetracycline; ERY, erythromycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; GEN, high-level resistance to gentamicin; KAN, high-level resistance to kanamycin; STR, high-level resistance to streptomycin; CHL, chloramphenicol; Q-D, quinupristin-dalfupristin. Antibiotic designations in parentheses represent variable resistance to the indicated antibiotic.

−, negative; +, positive.

ND, not done.

UTI, urinary tract infection.

CC5 E. faecium carrying vanA on large plasmids (>150 kb) spread among human and swine hosts from the EU and the United States.

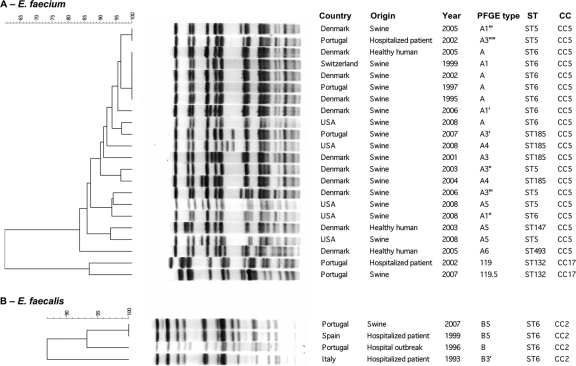

Thirty E. faecium isolates clustering in CC5 (17 ST6, 6 ST5, 5 ST185, 1 ST147, and 1 ST493) were obtained from swine samples from Denmark, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States, as well as from fecal samples from healthy Danes (1995 to 2008) (Table 2). Each ST comprised isolates recovered during a wide temporal and geographical frameshift that showed similar PFGE banding patterns (≤6 bands difference, >82% similarity [Fig. 1]): ST6 (1995 to 2008; 5 countries; subtypes A, A1, A1′, A1″, A1″′, and A2), ST5 (2003 to 2008; 2 countries; A1″″, A3″, A3″′, and A5), ST147 (2003; 1 country; A5), ST185 (2001 to 2008; 3 countries; A3, A3′, A4, and A4′), and ST493 (2005; 1 country; A6). The isolates were classified as clonally related following interpretive criteria using PFGE (48) and taking into account the similarity among MLST profiles (all STs were single- or double-locus variants [SLVs or DLVs, respectively] of ST6, with the exception of ST493, which differs in three alleles). These strains were similar to a CC5 epidemic VRE clone widespread among swine from different EU countries since the mid-1990s, and they were considered to be the same clone (35). Comparison with large collections of hospital VRE revealed two clonally related isolates causing urinary tract infections in patients from different Portuguese hospitals (ST5, subtype A3″″). These clinical isolates were not associated with a nosocomial outbreak.

Fig. 1.

Computer analysis of SmaI-digested genomic DNAs of representative vancomycin-resistant E. faecium (A) and E. faecalis (B) isolates from humans and swine. PFGE subtypes were established by visual analysis following the criteria of Tenover et al. (48). Computer analysis was performed with the Fingerprinting II Informatix software package (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The acquisition of the image was performed by using a Gel Doc XR camera (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.). The image was normalized by using four reference lanes of the low-range PFGE marker (0.13 kb to 1,018.5 kb; New England BioLabs, La Jolla, CA) as an external DNA size marker. The phylogenetic tree was subsequently constructed by use of the Dice coefficient and UPGMA clustering (optimization, 0.5%; band tolerance, 1.5%; threshold cutoff value set at 82%) (36). Year, year of isolation.

All human and animal isolates expressed tetM-mediated tetracycline resistance, and most isolates (25/30) were also resistant to erythromycin (ermB), while none contained the putative virulence gene esp or hyl. They all carried a deleted variant of Tn1546 previously designated type “D” and largely linked to swine hosts in different studies (26, 38, 54) and the gene tcrB coding for copper resistance, both located on large conjugative plasmids ranging from ca. 150 kb to 190 kb (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). All vanA plasmids carried a protein homologous to RepA of the recently sequenced megaplasmid pLG1 (GenBank accession number HM565183), which seems to be widespread among hospital E. faecium strains (29; A. R. Freitas and T. M. Coque, unpublished data).

CC17-ST132 E. faecium carrying Inc18-like vanA plasmids spread among human and swine hosts from Portugal.

One ST132-VREfm isolate from swine (n = 1) recovered in Portugal in 2007 showed a PFGE type identical to that of two Portuguese isolates causing urinary tract infections recovered in 2002 (14) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). ST132 is an SLV of ST18, a predominant clone of the CC17 polyclonal subcluster. Although ST132 is not a predominant CC17 clone, isolates belonging to the ST have been recovered from unrelated patients hospitalized in Portugal and Tanzania, and it has been associated with a nosocomial outbreak described in Spain during an 18-month period, suggesting potential transmissibility (14, 39, 43, 53; http://efaecium.mlst.net).

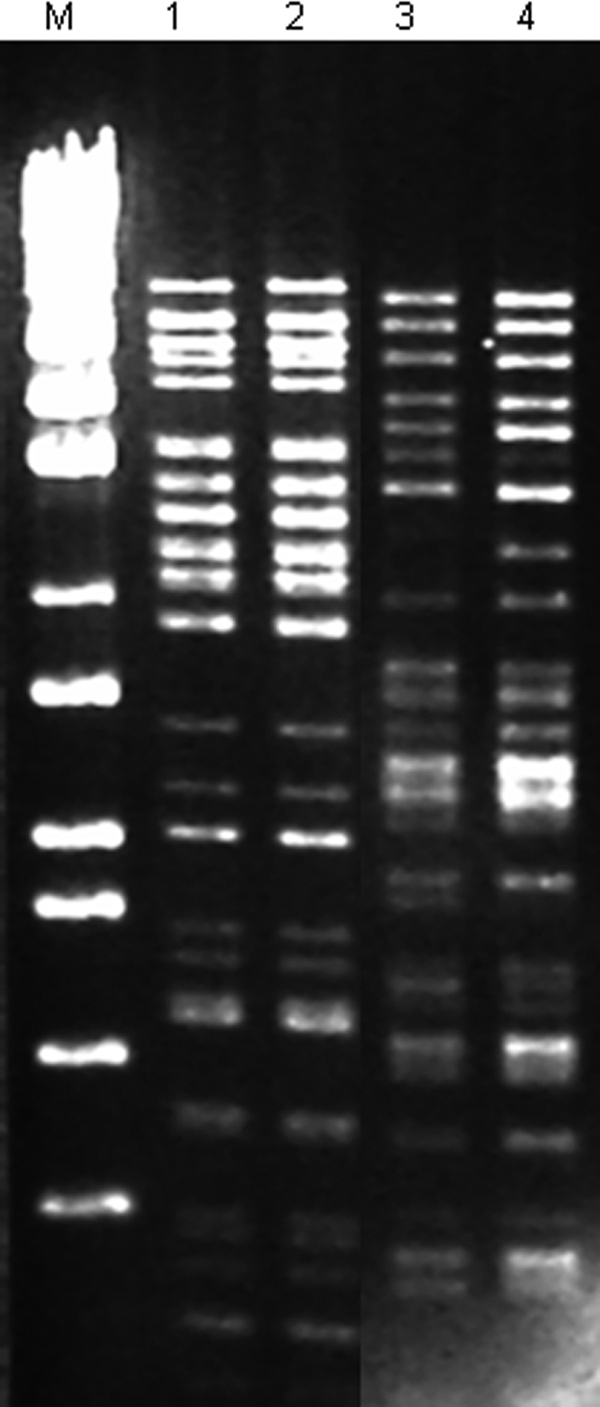

All three isolates expressed resistance to ampicillin, erythromycin, and glycopeptides and high levels of resistance (HLR) to gentamicin and kanamycin due to the presence of ermB, vanA, aac(6′)-aph(2″), and aph(3′)-IIIa genes. They also contained the esp gene, usually associated with a pathogenicity island of E. faecium (Table 2). Similar Tn1546 backbones identified in these isolates (all carried IS1216 within the vanX-vanY region and differed only upstream of vanR) were located on ca. 60-kb plasmids showing highly similar RFLP patterns (Fig. 2). Plasmid DNA hybridized with probes specific for homologues of replicases from the Inc18 plasmid pRE25 (rep2pRE25; GenBank accession no. X92945) and pRUM (rep17pRUM; GenBank accession no. AF507977). The vanA plasmid recovered from the clinical isolate contained a third rep highly homologous to pIP501 and other Inc18-like plasmids (rep1pIP501; GenBank accession no. AJ505823) and was the only transferable vancomycin-resistant plasmid harbored by the clone.

Fig. 2.

ClaI-digested plasmid DNAs of VRE isolates recovered from hospitals and swine from different origins. Lane M, molecular marker ladder EcoT 14 I/BglII (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan); lane 1, E. faecalis ST6-CC2 (PFGE B5) from an outbreak strain recovered in Spain in 1999; lane 2, E. faecalis ST6-CC2 (PFGE B5) from a swine isolate recovered in Portugal in 2007; lane 3, E. faecium ST132-CC17 (PFGE 119.5) from a swine isolate recovered in Portugal in 2007; lane 4, E. faecium ST132-CC17 (PFGE 119) from a clinical isolate recovered in Portugal in 2002 that is representative of strains causing urinary tract infections in two unrelated patients during 2002.

Plasmids showing an RFLP pattern identical to that identified in ST132 strains have also been observed among strains isolated from hospital sewage and the Douro river in Portugal over a long time. Although they belong to ST368 and ST369, which are SLVs of ST132, they showed different PFGE types (data not shown).

Although no clonal relationships with clinical or animal isolates were observed for the two PFGE types corresponding to the five E. faecium ST18 (CC17) isolates recovered from a healthy human during a 5-year period, it is of interest to highlight the relationship of the genetic elements of these strains with others described above. Both clones expressed resistance to ampicillin, erythromycin, and tetracycline, while they differed in susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and resistance to high levels of gentamicin and streptomycin (Table 2). Two Tn1546 variants, one containing an ISEf1 insertion, which is usually recovered from hospital VRE (previously designated PP5) (39), and the other associated with swine (type D), were linked to each PFGE type (Table 2), probably reflecting different acquisition events. The rep gene content was similar to that described above for other E. faecium CC17 isolates.

CC2-ST6 E. faecalis strains carrying pheromone-like vanA plasmids are disseminated among human and swine hosts in Europe.

The VREfs isolate recovered from Portuguese swine showed a PFGE type identical to that of a multidrug-resistant ST6-CC2 vanA E. faecalis strain isolated from Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish hospitals since at least 1993 (15) (Fig. 1). They commonly expressed resistance to tetracycline, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, and HLR to gentamicin, while HLR to kanamycin were seen and resistance to chloramphenicol was variable. The vanA, tetM, and aac(6′)-aph(2″) genes were detected in all four isolates, with the exception of the pig isolate, which lacked ermB but still contained aph(3′)-IIIa (Table 2). Like the majority of VREfs from Portuguese hospitals, the swine isolate did not contain esp (unpublished results).

A complete Tn1546 backbone was identified in all CC2-ST6 isolates analyzed except the Portuguese clinical isolate, in which an ISEf1 insertion was identified (36). Plasmids carrying Tn1546 ranged from 85 kb to 100 kb. The same ClaI-digested DNA pattern was observed among plasmids of ca. 100 kb from the Spanish clinical isolate (1999) and the Portuguese swine isolate (Fig. 2), which contained sequences homologous to those of replicases linked to pRE25 (rep2pRE25) and to pheromone-responsive plasmids pBEE99 and pTEF2 (rep9pCF10) (GenBank accession numbers NC_013533 and NC_004671, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The present study suggests interhost transmission of particular VRE strains belonging to predominant enterococcal clonal complexes associated with hospital-acquired human infections (E. faecium CC17 and E. faecalis CC2) or swine colonization (E. faecium CC5) in several European countries. The recovery from swine in Europe and the United States of an E. faecium CC5 clone with the ability to either colonize humans or cause human infections is of concern, and it might be added to the list of clonal lineages of Gram-positive organisms, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 or Staphylococcus pseudintermedius ST71, which are increasingly reported among animals and humans (46, 47). Although the origin and transmission routes of swine colonized by clonally related E. faecium CC5 isolates could not be established, inter- and intracountry food trade or dispersal of contaminated animals for food production cannot be ruled out. Contaminated imported chickens were suggested as the cause for clonal expansion of VREfs among poultry and pets in Japan and New Zealand during the last decade, although the isolates were not studied in detail at the genetic level (33, 40). Besides dispersal of animals in global markets, the selective pressure exerted by antibiotics (e.g., tetracyclines and β-lactams) or metals (e.g., copper) heavily used in veterinary medicine and husbandry may have contributed to the maintenance of VRE among swine farms and facilitated the horizontal transfer of conjugative plasmids to other enterococcal hosts (or other Gram-positive species serving as intermediates in the processes of horizontal gene transfer). Similarly to that described for E. faecium CC5, widespread clones of the predominant human enterococcal lineage E. faecium CC17 or E. faecalis CC2 have been recovered from companion and farm animals (4, 9, 13, 14).

Although some of the most common STs associated with E. faecium CC5 (ST5 and ST6), E. faecium CC17 (ST18), and E. faecalis CC2 (ST6) were detected, an unexpected diversity of STs and PFGE subtypes was observed within closely related E. faecium isolates belonging to CC5 and CC17. Examples of isolates showing the same or similar PFGE types but clustering in different STs have previously been described for both E. faecalis (13, 27) and E. faecium (7). It is known that large plasmids or integrative conjugative elements (ICEs), which are frequent in E. faecium (16, 21, 29, 55), can affect digested genomic DNA banding patterns (34, 49). In addition, a recent paper shows that mobilization of ICEs mediated by plasmids may also contribute to the diversity of housekeeping genes included in the MLST scheme (32). All these observations highlight not only the plasticity of enterococcal clones, which are able to evolve by diverse lateral transfer or mutational events, but also the potential difficulties in establishing epidemiological links among strains in some instances.

Confirming previous observations, specific Tn1546 variants were associated with VRE from humans or animals (10, 24, 38, 52, 54). The linking of such Tn1546 variants with particular plasmid types from E. faecium (megaplasmids and mosaic plasmids containing replication proteins belonging to the RepA_N family, such as those of pLG1 or pRUM, and Inc18) or E. faecalis (pheromone-responsive plasmids) is also in agreement with some recent studies (12, 25, 29, 44, 56). Rosvoll et al. recently described the presence of vanA-Inc18 plasmids containing one or two rep (rep1 and/or rep2) among E. faecium strains from poultry and farmers in Norway and Italy (44), some of them closely related to the first vanA-Inc18 plasmid recovered in France in 1986 from a clinical isolate (45). Other studies have also described the presence of large plasmids carrying Tn1546 among E. faecium isolates from hospitalized humans (2, 51) and swine (19). The recovery of resistant plasmids from clonally unrelated isolates from different sources over an extended period of time, such as that carried by the ST132 clone, is of concern, since it would reflect a wide spread and maintenance in both human and nonhuman hosts.

In summary, this study documents that enterococcal clones belonging to host-adapted clonal complexes of E. faecium (CC5 and CC17) and E. faecalis (CC2) are shared by swine and humans. The fact that these clones are able to colonize and cause human infections (and, in some instances, nosocomial outbreaks, such as E. faecium ST132 or E. faecalis ST6) confirms the relevance of reverse and alternative routes for dissemination of commensal and opportunistic bacteria. Multilayered molecular epidemiology studies will be required to understand the spread and evolution of clones and genetic elements encoding vancomycin resistance and overcoming the species barriers between humans and swine.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Ana R. Freitas was supported by fellowships from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia of Portugal (SFRH/BD/24604/2005) and the European Union (LSHE-2007-037410). Research on enterococci was supported by grants from the European Union (LSHE-2007-037410), from the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain (PI07/1441, PS09/02381), and from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia of Portugal (POCI/AMB/61814/2004).

We thank Maria del Grosso and Annalisa Pantosti (Instituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy), Patrice Boerlin (Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada), Patricia Ruiz-Garbajosa (Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain), and Inmaculada Herrero and Miguel A. Moreno (Veterinary School, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain) for the gift of strains. We are also grateful to the Spanish Network for the Study of Plasmids and Extrachromosomal Elements (REDEEX) for encouraging and funding cooperation among Spanish microbiologists working on the biology of mobile genetic elements (Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain, BFU 2008-0079-E/BMC).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org.

Published ahead of print on 12 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Agersø Y., et al. 2008. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis isolates from a Danish patient and two healthy human volunteers are possibly related to isolates from imported turkey meat. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:844–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arias C. A., Panesso D., Singh K. V., Rice L. B., Murray B. E. 2009. Cotransfer of antibiotic resistance genes and a hylEfm-containing virulence plasmid in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4240–4246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bates J., Jordens J. Z., Griffiths D. T. 1994. Farm animals as a putative reservoir for vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infection in man. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 34:507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biavasco F., et al. 2007. VanA-type enterococci from humans, animals, and food: species distribution, population structure, Tn1546 typing and location, and virulence determinants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3307–3319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boerlin P., Wissing A., Aarestrup F. M., Frey J., Nicolet J. 2001. Antimicrobial growth promoter ban and resistance to macrolides and vancomycin in enterococci from pigs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4193–4195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute 2010. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 20th informational supplement M100-S20, vol. 30 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coque T. M., et al. 2005. Population structure of Enterococcus faecium causing bacteremia in a Spanish university hospital: setting a scene for a future increase in vancomycin resistance? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2693–2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dahl K. H., Simonsen G. S., Olsvik O., Sundsfjord A. 1999. Heterogeneity in the vanB gene cluster of genomically diverse clinical strains of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1105–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Damborg P., et al. 2009. Dogs are a reservoir of ampicillin-resistant Enterococcus faecium lineages associated with human infections. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:2360–2365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Descheemaeker P. R. M., et al. 1999. Comparison of glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates and glycopeptide resistant genes of human and animal origins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2032–2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Donabedian S. M., et al. 2010. Characterization of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolated from swine in three Michigan counties. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:4156–4160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Freitas A. R., et al. 2008. Plasmid characterization of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis strains from different continents (1989–2004), abstr. 2112, p. S624 Abstr. 18th Eur. Congr. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. (Barcelona, Spain). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Freitas A. R., Novais C., Ruiz-Garbajosa P., Coque T. M., Peixe L. 2009. Clonal expansion within clonal complex 2 and spread of vancomycin-resistant plasmids among different genetic lineages of Enterococcus faecalis from Portugal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:1104–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Freitas A. R., Novais C., Ruiz-Garbajosa P., Coque T. M., Peixe L. 2009. Dispersion of multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates belonging to major clonal complexes in different Portuguese settings. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4904–4908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Freitas A. R., et al. 2008. Genetic dynamics of a successful Enterococcus faecalis clone persistently recovered from European hospitals during the last decade (1993–2008), abstr. C2-1996. Abstr. 48th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freitas A. R., et al. 2010. Global spread of the hylEfm colonization-virulence gene in megaplasmids of the Enterococcus faecium polyclonal subcluster. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2660–2665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hammerum A. M., et al. 2004. A vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolate from a Danish healthy volunteer, detected 7 years after the ban of avoparcin, is possibly related to pig isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:547–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hasman H., et al. 2006. Copper resistance in Enterococcus faecium, mediated by the tcrB gene, is selected by supplementation of pig feed with copper sulfate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5784–5789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hasman H., Villadsen A. G., Aarestrup F. M. 2005. Diversity and stability of plasmids from glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium (GRE) isolated from pigs in Denmark. Microb. Drug Resist. 11:178–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hayes J. R., et al. 2003. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Enterococcus species isolated from retail meats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7153–7160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hegstad K., Mikalsen T., Coque T. M., Werner G., Sundsfjord A. 2010. Mobile genetic elements and their contribution to the emergence of antimicrobial resistant Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:541–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Herrero I. A., Teshager T., Garde J., Moreno M. A., Dominguez L. 2000. Prevalence of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VREF) in pig faeces from salughterhouses in Spain. Prev. Vet. Med. 47:255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hidron A. I., et al. 2008. NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006–2007. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 29:996–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jensen L. B., et al. 1998. Molecular analysis of Tn1546 in Enterococcus faecium isolated from animals and humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:437–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jensen L. B., et al. 2010. A classification system for plasmids from enterococci and other Gram-positive bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 80:25–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jensen L. B., Hammerum A. M., Poulsen R. L., Westh H. 1999. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium strains with highly similar pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns containing similar Tn1546-like elements isolated from a hospitalized patient and pigs in Denmark. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:724–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kawalec M., et al. 2007. Clonal structure of Enterococcus faecalis isolated from Polish hospitals: characterization of epidemic clones. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:147–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Larsen J., et al. 2010. Porcine-origin gentamicin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis in humans, Denmark. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:682–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Laverde Gomez J. A., et al. 2011. A multiresistance megaplasmid pLG1 bearing a hylEfm genomic island in hospital Enterococcus faecium isolates. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 301:165–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leavis H. L., Bonten M. J., Willems R. J. 2006. Identification of high-risk enterococcal clonal complexes: global dispersion and antibiotic resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:454–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lu H. Z., et al. 2002. Enterococcus faecium-related outbreak with molecular evidence of transmission from pigs to humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:913–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Manson J. M., Hancock L. E., Gilmore M. S. 2010. Mechanism of chromosomal transfer of Enterococcus faecalis pathogenicity island, capsule, antimicrobial resistance, and other traits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:12269–12274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Manson J. M., Keis S., Smith J. M., Cook G. M. 2003. Characterization of a vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis (VREF) isolate from a dog with mastitis: further evidence of a clonal lineage of VREF in New Zealand. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3331–3333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morrison D., Woodford N., Barrett S. P., Sisson P., Cookson B. D. 1999. DNA banding pattern polymorphism in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium and criteria for defining strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1084–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Novais C., et al. 2005. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium clone in swine, Eur. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:1985–1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Novais C., Coque T. M., Sousa J. C., Baquero F., Peixe L. 2004. Local genetic patterns within a vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis clone isolated in three hospitals in Portugal. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3613–3617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Novais C., Coque T. M., Sousa J. C., Peixe L. V. 2006. Antimicrobial resistance among faecal enterococci from healthy individuals in Portugal. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12:1131–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Novais C., et al. 2008. Diversity of Tn1546 and its role in the dissemination of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in Portugal. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1001–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Novais C., Sousa J. C., Coque T. M., Peixe L. V. 2005. Molecular characterization of glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates from Portuguese hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3073–3079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ozawa Y., et al. 2002. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci in humans and imported chickens in Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6457–6461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Phillips I., et al. 2004. Does the use of antibiotics in food animals pose a risk to human health? A critical review of published data. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:28–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Phillips I. 2007. Withdrawal of growth-promoting antibiotics in Europe and its effects in relation to human health. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30:101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Romo M., Tomita H., Ike Y., Martínez-Martínez L., Francia M. 2007. Emergence of worldwide epidemic clones of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium in a Northern Spain hospital, abstr. 681, p. S163 Abstr. 17th Eur. Congr. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. (Munich, Germany). [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rosvoll T. C., et al. 2010. PCR-based plasmid typing in Enterococcus faecium strains reveals widely distributed pRE25-, pRUM-, pIP501-, and pHTbeta-related replicons associated with glycopeptide resistance and stabilizing toxin-antitoxin systems. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 58:254–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sletvold H., et al. 2010. Tn1546 is part of a larger plasmid-encoded genetic unit horizontally disseminated among clonal Enterococcus faecium lineages. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1894–1906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Smith T. C., et al. 2009. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain ST398 is present in Midwestern U.S. swine and swine workers. PLoS One 4:e4258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stegmann R., Burnens A., Maranta C. A., Perreten V. 2010. Human infection associated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius ST71. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:2047–2048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tenover F. C., et al. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thal L. A., Silverman J., Donabedian S., Zervos M. J. 1997. The effect of Tn916 insertions on contour-clamped homogeneous electrophoresis patterns of Enterococcus faecalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:969–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Werner G., et al. 2008. Emergence and spread of vancomycin resistance among enterococci in Europe. Euro Surveill. 13:ii=19046 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Werner G., Klare I., Witte W. 1999. Large conjugative vanA plasmids in vancomycin-resistant E. faecium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2383–2384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Willems R. J., et al. 1999. Molecular diversity and evolutionary relationships of Tn1546-like elements in enterococci from humans and animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:483–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Willems R. J., van Schaik W. 2009. Transition of Enterococcus faecium from commensal organism to nosocomial pathogen. Future Microbiol. 4:1125–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Woodford N., Adebiyi A. M. A., Palepou M. F. I., Cookson B. D. 1998. Diversity of VanA glycopeptide resistance elements in enterococci from humans and nonhuman sources. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:502–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang X., Vrijenhoek J. E., Bonten M. J., Willems R. J., Van Schaik W. 2010. A genetic element present on megaplasmids allows Enterococcus faecium to use raffinose as carbon source. Environ. Microbiol. doi:10.1111/j.1462–2920.2010.02355.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhu W., et al. 2010. Dissemination of an Enterococcus Inc18-Like vanA plasmid, associated with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4314–4320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.