Abstract

Ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma (OPA) is a transmissible lung cancer of sheep caused by Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus (JSRV). The details of early events in the pathogenesis of OPA are not fully understood. For example, the identity of the JSRV target cell in the lung has not yet been determined. Mature OPA tumors express surfactant protein-C (SP-C) or Clara cell-specific protein (CCSP), which are specific markers of type II pneumocytes or Clara cells, respectively. However, it is unclear whether these are the cell types initially infected and transformed by JSRV or whether the virus targets stem cells in the lung that subsequently acquire a differentiated phenotype during tumor growth. To examine this question, JSRV-infected lung tissue from experimentally infected lambs was studied at early time points after infection. Single JSRV-infected cells were detectable 10 days postinfection in bronchiolar and alveolar regions. These infected cells were labeled with anti-SP-C or anti-CCSP antibodies, indicating that differentiated epithelial cells are early targets for JSRV infection in the ovine lung. In addition, undifferentiated cells that expressed neither SP-C nor CCSP were also found to express the JSRV Env protein. These results enhance the understanding of OPA pathogenesis and may have comparative relevance to human lung cancer, for which samples representing early stages of tumor growth are difficult to obtain.

Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus (JSRV) is an oncogenic betaretrovirus that causes ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma (OPA), a chronic respiratory disease of sheep (30, 34). OPA is common in many sheep-rearing countries and has important economic and welfare implications for the agricultural industry. The primary route of disease transmission is by inhalation of the virus, which then infects epithelial cells in the lung, initiating oncogenesis and tumor growth. Tumors develop in the bronchiolar and alveolar regions of the lung, forming acinar and papillary proliferations which expand into adjacent structures (14, 19, 23-24, 64). As the tumors grow, gas exchange in respiratory airways becomes compromised, and clinical signs of labored breathing and weight loss develop. In some sheep, tumor expansion is accompanied by the production of virus-rich fluid which pours from the nose when the hind end of the animal is lifted (34, 74). In natural infections, clinical signs develop after a prolonged incubation period, but once detected, the disease is invariably fatal (5). Experimentally infected animals show age-dependent susceptibility, with younger lambs developing clinical disease more rapidly than older lambs or adult sheep (73).

In addition to its veterinary importance, JSRV has attracted interest for fundamental studies of viral carcinogenesis. This is because the viral Env protein is oncogenic and capable of inducing neoplastic transformation in vitro (46, 66) and in vivo (6, 8, 12, 17, 87). The transforming activity is thought to require specific residues in the cytoplasmic tail of the transmembrane (TM) domain of Env (58), although the surface glycoprotein (SU) component has also been proposed to have a role (18, 36). Studies of transformed cell lines have identified the activation of several signaling pathways in response to Env expression, particularly the MEK-ERK and PI3K-Akt pathways, suggesting their involvement in neoplastic transformation (45).

Histological similarities between OPA and human lung tumors have been recognized for many years (4), and OPA is regarded as a natural animal model for human lung adenocarcinomas of mixed subtypes (21, 51, 57). A retroviral etiology for these human tumors has been suggested, and some cases have been shown to express an antigen related to betaretroviral Gag proteins (20, 22, 38). However, additional markers of retroviral infection in these patients have not been found (38).

Despite the potential value of OPA as a model system, interactions between JSRV and its host during the early stages of infection are not fully understood. For example, the cell type(s) initially infected and transformed by JSRV has not been defined. Identification of the target cell(s) is an important step toward understanding the pathogenesis of OPA. In vitro experiments to examine JSRV tropism have been hindered by the difficulty of maintaining the required ovine cell phenotypes in culture for a prolonged period (1, 41). JSRV cell tropism is thought to be determined by a requirement for lung-specific transcription factors. Evidence supporting this comes from luciferase reporter assays that showed the JSRV long terminal repeat (LTR) to be preferentially active in cell lines derived from Clara cells and type II pneumocytes (48, 55). In contrast, the cellular receptor for JSRV (hyaluronidase-2) is not thought to be a significant determinant of tropism, as it is expressed by a broad range of cells (50, 66). Other host proteins that might influence JSRV tropism include restriction factors such as TRIM5α, APOBEC, and tetherin (53). In addition, the sheep genome contains at least 27 endogenous proviruses closely related to JSRV, denoted enJSRVs (2). Most enJSRV proviruses are defective, but some express viral proteins (Gag and Env) that can interfere with the replication of infectious JSRV (52, 59, 78). However, enJSRV proviruses do not exhibit significant expression in the lung but instead are expressed predominantly in reproductive tissues, where they have a role in placental development (25).

Mouse models have provided some information on JSRV target cells in vivo. For example, in transgenic mice carrying a beta-galactosidase reporter gene under the control of the JSRV LTR, reporter activity was predominantly restricted to type II pneumocytes (16). In a separate study, infection of mice with adeno-associated virus vectors expressing JSRV Env resulted in tumors with a bronchioloalveolar distribution similar to those seen in sheep (87). While these models are informative, mice do not have a functional receptor for JSRV (50) and so have not been used for studies of cell tropism using infectious wild-type JSRV. In addition, there are differences in gross and cellular lung anatomy between sheep and mice (65) that could potentially affect the distribution and abundance of the cells targeted for infection.

Natural field cases of OPA have also been studied. However, tissues obtained from these animals do not represent the initial stages of infection which are required for identification of the target cell in the lung. Immunohistochemical studies of mature OPA tumors have shown the majority of the neoplastic cells to express surfactant protein-C (SP-C), while a smaller proportion express Clara cell-specific protein (CCSP) (3, 64). SP-C and CCSP are specific markers of type II alveolar pneumocytes and bronchiolar Clara cells, respectively. Consequently, both of these cell types have been proposed as potential target cells for JSRV (3, 64, 74). An alternative explanation for the mixed tumor phenotype would be that JSRV infects a stem cell in the distal lung (64), which subsequently gives rise to cells expressing different lineage markers. The role of stem cells in lung cancer has attracted significant interest in recent years (9, 26). The cancer stem cell (CSC) model was developed to explain the heterogeneous nature of many tumors and proposes that the same cellular hierarchical organization that exists in normal tissues is also present in tumors (69). This means that CSCs can self-renew and produce differentiated progeny, giving them the ability to initiate tumors and promote their progression (26). This model has clinical relevance, as CSCs are reported to be more resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy than other tumor cells (85).

Identification of endogenous stem cells in the lung is difficult because the rate of cell turnover is relatively slow. For this reason, lung injury models have been used to categorize respiratory epithelial cells according to their progenitor potential. In the normal mouse lung, Clara cells and type II pneumocytes are recognized as facultative progenitor cells, capable of maintaining epithelial integrity in the steady state (80). However, naphthalene-induced injury models have identified a subpopulation of “variant Clara cells” located in stem cell niches at neuroepithelial bodies (NEBs) and at the bronchioloalveolar duct junction (BADJ). These cells were shown to be resistant to naphthalene injury and capable of repopulating damaged bronchiolar epithelium (32, 37, 42, 70). A subset of variant Clara cells at the BADJ were also found to coexpress SP-C and CCSP and were denoted bronchioloalveolar stem cells (BASCs) (42). These cells have been proposed as the cell of origin for K-ras-induced adenocarcinoma in a murine lung cancer model (42).

The aim of this study was to identify the target cell(s) for JSRV infection in the lung and to investigate the potential importance of stem cells as the cell of origin for OPA. Experimentally infected lambs were used to provide lung tissue from early stages of infection. Postmortem samples were taken before significant tumor growth had occurred, and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) and immunolabeling techniques were applied to detect virus RNA and to identify the phenotype of single cells that were positive for JSRV Env. Target cells were found in conducting and respiratory airways and were CCSP or SP-C positive. Cells expressing JSRV Env but not CCSP, SP-C, or synaptophysin (a neuroepithelial cell marker) were also identified in the bronchiolar region. It was not possible to detect significant numbers of ovine BASC-like cells in control or infected lambs with or without tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of JSRV21 and mock inoculate.

293T cells were grown in 225-cm2 flasks in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 4 mM glutamine at 37°C, with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. The cells were transfected with the JSRV molecular clone pCMV2JS21 essentially as described previously (60), except that transfection complexes were prepared using 56 μg plasmid DNA and 81 μl FuGene HD transfection reagent (Roche) for each culture flask. The medium was replaced after 24 h and then harvested 48 and 72 h posttransfection and pooled. Harvested supernatant was then filtered through a 0.45-μm cellulose acetate filter (Sartorius) and concentrated by ultracentrifugation through a glycerol cushion at 100,000 × g for 3 h before resuspending the viral pellet in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a 200× concentration. The virus was quantified by qRT-PCR as described previously (13). Each lamb received a dose equivalent to approximately 1010 RNA copies of JSRV21 in a total volume of 4 ml. The inoculum for negative-control animals was prepared by harvesting medium from untransfected 293T cells and processing it in the same way.

Intratracheal inoculation of specific-pathogen-free lambs.

All animal experiments were approved by the Moredun Research Institute (MRI) Local Ethical Review Committee and carried out in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Twenty-four Scottish Blackface lambs were born and housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions. At 6 days old, 12 lambs were inoculated with JSRV21, and 6 lambs were mock inoculated with 293T culture supernatant. Inoculations were performed by injection into the tracheal lumen. The remaining 6 lambs were not inoculated. The lambs inoculated with JSRV21 were housed in a different containment room from the mock-inoculated and noninoculated negative-control lambs. Male and female lambs were equally distributed between all groups.

Postmortem sample collection.

At 3 and 10 days postinoculation, 4 JSRV21-infected, 2 mock-inoculated, and 2 noninoculated lambs were euthanized. Thereafter, infected animals were culled when clinical signs became apparent between 72 to 91 days of age, and one or two age-matched control lambs were culled at the same time. Positive-control samples were taken from adult animals showing clinical signs of OPA collected from local farms. Adult negative-control animals were taken from a flock in which no cases of OPA had been diagnosed in the previous 5 years. The procedure for tissue collection followed a fixed protocol and was carried out as quickly as possible to minimize postmortem artifacts. The lung was prepared for sampling using a sharp blade to section all lobes into 5-mm-thick segments along the horizontal axis. Samples were taken from 24 fixed sites throughout the lung and immersed in 4% formal saline for 7 days before routine processing and embedding in paraffin wax. Adjacent samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C in preparation for RNA extraction.

qRT-PCR.

RNA was extracted from lung cryostats using a commercially available kit (RNeasy minikit; Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA concentration was quantified using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer, and the purity determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. qRT-PCR was performed using an ABI Prlsm 7000 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and the TaqMan one-step RT-PCR master mix reagents kit (Applied Biosystems). All samples were run in duplicate with 100 ng of RNA in a 20-μl final reaction volume. Primers and amplification conditions used were as described previously (13).

Immunohistochemistry.

Tissue sections (5 μm) were placed on Superfrost Plus slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through 100%, 75%, and 50% ethanol. Epitope retrieval was performed by autoclaving the slides at 121°C for 10 min in citrate buffer (10 mM citric acid, pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by immersion in 3% (vol/vol) H2O2-methanol for 20 min. Tissues were rinsed with running tap water for 5 min and incubated with 150 μl of 25% normal goat serum (NGS; Vector) in PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) for an hour at room temperature. The 25% NGS-PBST was replaced with primary antibody (diluted in 25% NGS-PBST) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Following this, slides were rinsed three times with PBST and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit) for 30 min at room temperature. Sections were rinsed three times in PBST and incubated with an appropriate antigen visualization system. The dilutions used and sources of the primary antibodies for this study are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Antibodies used in this study

| Antibody | Target | Dilution |

Source (product no.) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light microscopy | Immunofluorescence | ||||

| Anti-pan-cytokeratin | Epithelial cells | 1/1,000 | Not used | Dako (M3515) | 77 |

| Anti-Ki-67 | Proliferating cells | 1/1,000 | 1/1,000 | Dako (M7240) | 47 |

| Anti-CCSP | Clara cells | 1/20,000 | 1/2,000 | Claudio Murgia | Unpublished |

| Anti-SP-C | Type II pneumocytes | 1/4,000 | 1/2,000 | Jeffrey Whitsett | 64 |

| Anti-JSRV SU | JSRV SU | 1/800 | 1/400 | Dusty Miller | 88 |

| Anti-synaptophysin | Neuroepithelial cells | 1/50 | 1/50 | Vector (VPS284) | 33 |

For each primary antibody, negative controls included samples that were incubated with isotype-matched preimmune or normal serum from the same species that raised the primary antibody. In addition, the primary antibody was omitted to check for nonspecific labeling of the secondary antibody or the visualization system. For multiple labeling techniques, primary antibodies were omitted from successive layers and substituted with 25% NGS-PBST or nonimmune serum. The order in which antibodies were applied was also reversed to ensure that antibodies were not masking each other. An additional single sample of lung was obtained from an adult animal with a lung tumor that was not caused by JSRV, and this was used to confirm the specificity of the anti-JSRV SU monoclonal antibody.

Indirect labeling.

Indirect labeling techniques to detect single and multiple antigens in the section used the Envision system (Dako), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Substrate chromogens used for bright-field microscopy were 3,3′diaminobenzidine (DAB) and Vector VIP (Vector Labs). The tyramide signal amplification (TSA) kit (Molecular Probes) was used for fluorescent labeling of antigen. Alexa Fluor 488 and 568 tyramide were used to detect the antigen. A 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) counterstain was used to highlight cellular nuclei and was applied within an antifade mountant (ProLong Gold antifade reagent; Invitrogen).

Direct labeling of anti-CCSP antibody.

Fluorescence-labeled fragment antigen-binding (Fab) fragments were used to detect CCSP antigen. The anti-CCSP antibody was incubated with a goat anti-rabbit Fab 649 fragment (DyLight 649-conjugated AffiniPure Fab fragment; Jacksons ImmunoResearch) at a 1:2 (vol/vol) ratio for 5 min in the dark at room temperature. This solution was then mixed with 10% normal rabbit serum, and the solution was incubated in the dark for a further 10 min. The mixture was then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g, and 150 μl was incubated with the tissue overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed three times in PBS before mounting, prior to examination with the appropriate filter set.

Multiple labeling.

Combinations of these techniques were employed to label multiple antigens in one section. Fluorescent labels with distinct emission spectra were chosen, and the conditions for each antibody were optimized on tissue from the JSRV21-infected lambs with clinical disease. For double labeling using antibodies raised in different species (i.e., mouse monoclonal and rabbit polyclonal antibodies), the indirect technique was used. Antigen visualization was achieved using a combination of the chromogens DAB and Vector VIP or tyramide Alexa Fluor 488 and tyramide Alexa Fluor 568. Triple labeling combined both direct and indirect techniques. Initially, double labeling was performed, and the section was then incubated overnight with Fab 649-labeled-anti-CCSP antibody before being rinsed and mounted.

Image acquisition and analysis.

Images for bright-field microscopy were examined using an Olympus BX51 microscope, and photographs were captured with an Olympus DP70 camera with analySIS software (Soft Imaging System GmbH, Münster, Germany). Fluorescence microscopy was performed with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M inverted epifluorescence microscope and AxioVision 4.7.1 software. An ApoTome device (Zeiss) was used to achieve optical sectioning by structured illumination to construct a Z-stack and 3-D images when required.

RESULTS

Validation of the experimental disease model of OPA.

Experimentally infected lambs were used to provide lung tissue from early stages of JSRV infection. Twelve 6-day-old lambs were inoculated with cell culture-derived JSRV21 by intratracheal delivery. Previous studies have established this as a reproducible disease model for OPA (6, 12, 60, 73). Age-matched control lambs were either mock inoculated using 293T cell culture supernatants or not inoculated. Groups of 4 infected lambs and 4 controls were culled 3 and 10 days postinoculation. Thereafter, individual infected lambs (n = 4) along with an age-matched negative control were culled when clinical signs of OPA developed (72 to 91 days). Histological examination of lung tissues confirmed the presence of tumors in all 4 infected animals with clinical signs of respiratory disease but not in control lambs. The tumor morphology of experimentally induced OPA (OPA-E) was similar to that found in natural field cases of OPA (OPA-N) (Fig. 1A and B).

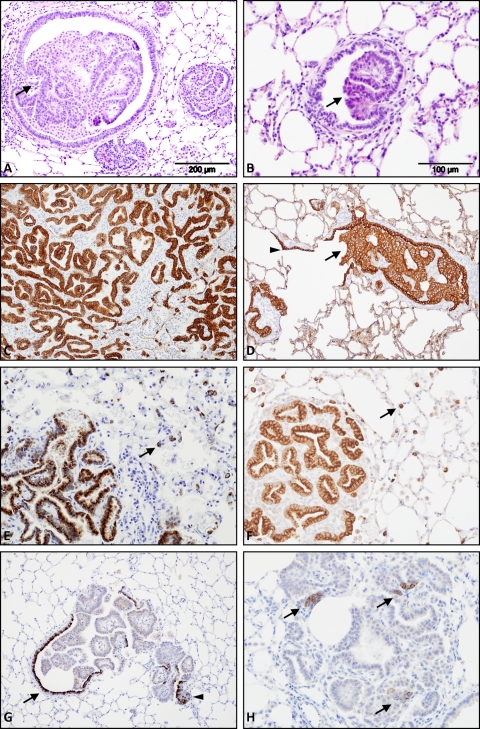

FIG. 1.

Validation of the OPA experimental model. The morphology and protein expression of tumors from clinical cases of OPA-N and OPA-E (72 to 91 days postinoculation) were compared using hematoxylin and eosin staining (A, B) and immunohistochemistry (C to H). (A) OPA-N shows papillary adenocarcinoma within a bronchiole (arrow) and the adjacent alveolar tissue. (B) OPA-E shows early papillary adenocarcinoma emanating from the bronchiolar epithelium (arrow). (C) OPA-N shows strong cytoplasmic labeling of all tumor cells (in brown) with an antibody to pan-cytokeratin, an epithelial cell marker. Original magnification (OM), ×100. (D) OPA-E shows strong cytoplasmic labeling of tumor cells with anti-pan-cytokeratin antibody within a bronchiole (arrow). Normal respiratory epithelium (arrowhead) is also labeled. OM, ×100. (E, F) OPA-N (E) and OPA-E (F) show strong cytoplasmic labeling of tumor cells (in brown) with anti-surfactant protein-C antibody. Specific labeling of normal type II pneumocytes in the alveolar region (arrows) is also visible. OM, ×200. (G) OPA-E is labeled with anti-CCSP antibody. There is strong cytoplasmic labeling of Clara cells in the normal bronchial epithelium (arrow) and occasional tumor cells (arrowhead). OM, ×100. (H) OPA-E is labeled with anti-synaptophysin antibody, a marker of neuroendocrine differentiation. Multiple positive foci are visible within this neoplastic growth (arrows), which was in contrast to cases of OPA-N, where similar cells were not readily detectable (not shown). OM, ×200.

In order to validate this experimental model of disease, tumor phenotypes from clinical cases of OPA-E (lambs culled 72 to 91 days postinfection) and OPA-N were compared using immunohistochemistry (IHC). Sections were labeled with antibodies against cytokeratin (an epithelial cell marker), surfactant protein-C (SP-C) (a type II pneumocyte marker), Clara cell-specific protein (CCSP) (a Clara cell marker), and synaptophysin (a neuroepithelial cell marker). Both OPA-N and OPA-E labeled strongly with anti-cytokeratin antibody, confirming the epithelial origin of the tumor (Fig. 1C and D). Anti-SP-C antibody (a generous gift from Jeffrey Whitsett) also labeled tumor cells in both OPA-N and OPA-E (Fig. 1E and F). This demonstrates that the majority of transformed cells express a marker of type II pneumocytes, which is in agreement with previous studies (3, 64). Analysis of lung tissues with anti-CCSP antibody (a generous gift from Claudio Murgia) found strong labeling of occasional cells toward the periphery of the tumor at the junction of normal bronchiolar and neoplastic epithelia in OPA-E (Fig. 1G; see also Fig. S1F in the supplemental material). Extensive tumor growth prevented identification of this specific region in OPA-N. Weak punctate cytoplasmic labeling of CCSP was seen in some tumor nodules in cases of OPA-E and OPA-N (data not shown). An anti-synaptophysin antibody detected occasional clusters of positive cells in OPA-E (Fig. 1H) but not in OPA-N (data not shown).

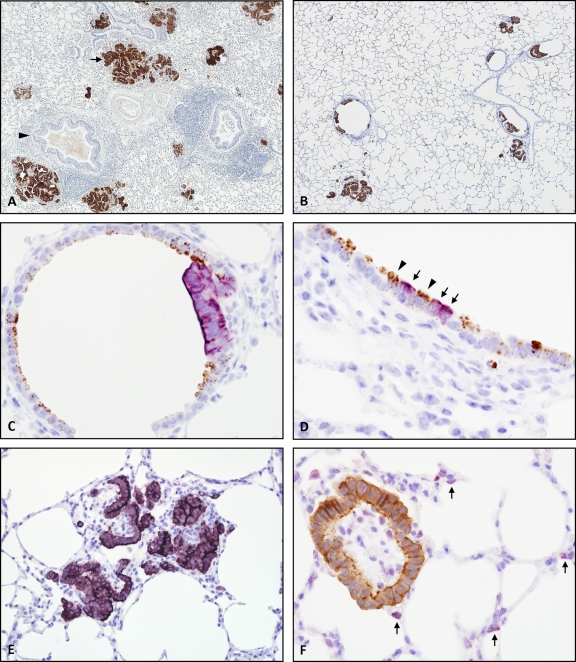

Previous work has demonstrated that almost all tumor cells in OPA express the JSRV Env protein (73, 88). This was confirmed in the present study by IHC using a monoclonal antibody to JSRV SU (a generous gift from Dusty Miller). The specificity and sensitivity of this antibody were initially tested on clinical cases of OPA-N, where inflammation and necrosis frequently complicate the pathology. Exclusive labeling of tumor cells was apparent in all OPA samples examined. In addition, a non-OPA sheep lung tumor did not label with this antibody (data not shown). The pattern of labeling in OPA-E was similar to that found in OPA-N (Fig. 2 A and B), although overall tumor volume was less extensive in OPA-E. Foci of JSRV-expressing cells in OPA-E were located in conducting and respiratory airways, and this was verified using two-color IHC to detect JSRV SU and CCSP or SP-C (Fig. 2C to F). These results confirmed that this experimental model of OPA was representative of natural disease.

FIG. 2.

JSRV expression and tumor localization in OPA-N and OPA-E. Immunohistochemistry was performed using the Envision system and formalin-fixed tissue which had undergone antigen retrieval in citrate buffer, pH 6.0, at 121°C for 10 min. DAB chromogen (brown) and VIP (purple) substrates were used for antigen visualization. (A) OPA-N showing specific labeling of tumor foci with anti-JSRV SU antibody (arrow) but not of the normal bronchial epithelium (arrowhead). OM, ×20. (B) OPA-E showing multiple tumor nodules in conducting and respiratory airways labeling with anti-JSRV SU antibody. OM, ×40. (C) OPA-E showing respiratory bronchiole with a neoplastic cluster. Clara cells lining the bronchiole label with anti-CCSP antibody (in brown), and the tumor labels with anti-JSRV SU antibody (in purple). OM, ×400. (D) OPA-E showing terminal bronchiole. Normal Clara cells label with anti-CCSP antibody (in brown; arrowheads), and adjacent individual cells express JSRV SU (in purple; arrows). OM, ×400. (E) OPA-E showing alveolar region. Anti-JSRV SU antibody labels tumor clusters (in purple). OM, ×200. (F) OPA-E, alveolar region, contains a neoplastic cluster which labels with anti-JSRV SU antibody (in brown). Normal type II pneumocytes expressing SP-C (in purple; arrows) are visible in the background confirming the alveolar location. OM, ×400.

Detection of JSRV RNA expression in OPA-E.

Following validation of the experimental tumor model in lambs exhibiting clinical signs of OPA (i.e., 72 to 91 days postinoculation), lung tissues from lambs at 3 days and 10 days postinfection were analyzed for JSRV expression. Initially, this was done by qRT-PCR using primers that amplify a fragment of the Env-LTR region of the JSRV genome. Samples were analyzed from five fixed sites in all lobes of the left lung from all infected and negative-control lambs at 3 and 10 days postinoculation. Tissues collected from clinical cases of OPA-E and OPA-N were used as positive-control samples. JSRV RNA was detected in the lungs of the 4 JSRV-infected lambs killed 10 days postinoculation but not in those of negative-control animals of the same age or in those of any lamb killed 3 days postinoculation (data not shown). As expected, the qRT-PCR analysis found higher levels of JSRV RNA in OPA-E cases, which have extensive tumors, than in lambs killed 10 days postinoculation, which had no clinical signs of OPA (data not shown).

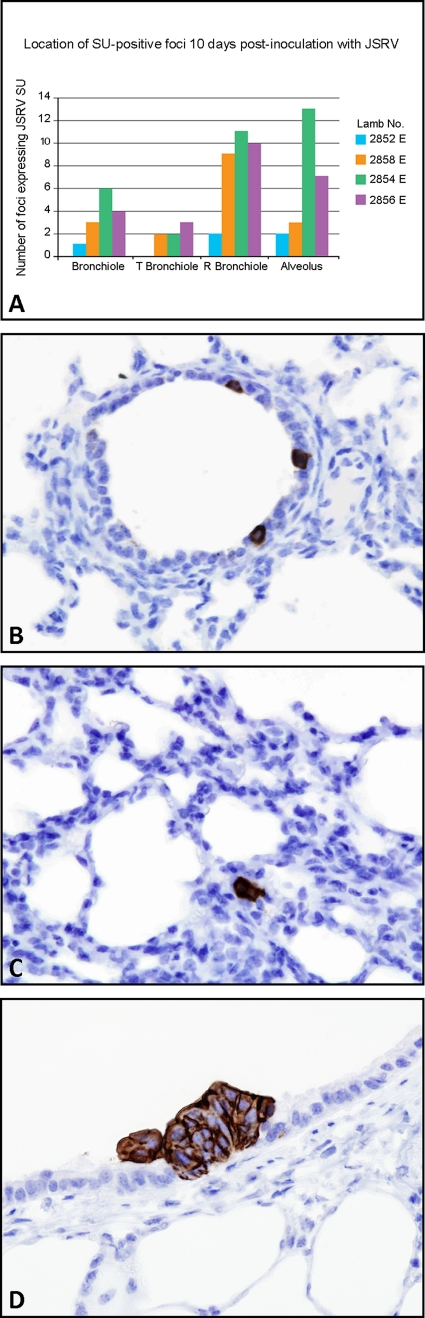

Detection of early JSRV Env-positive foci in conducting and respiratory airways.

In order to identify the anatomical location of foci of JSRV-positive cells at early time points postinfection, IHC for JSRV SU on lung tissues taken from lambs at 3 days and 10 days postinfection was performed. Samples were taken from 24 fixed sites distributed throughout the lung of each lamb, 5 of which were adjacent to those sites examined by qRT-PCR. No JSRV-positive cells were identified in any of the tissue sections taken from lambs at 3 days postinoculation, consistent with the qRT-PCR results. However, in lung tissue taken from lambs with JSRV at 10 days postinoculation, distinct SU-positive cells were observed either as single cells or small clusters of positively labeling cells. A total of 96 lung sections were examined from the 4 infected lambs, and in these, 78 JSRV SU-positive foci were identified (Fig. 3A). The location of each JSRV SU-positive focus was assigned to one of five anatomical regions in the lung as defined by Tyler (84). In the sheep, the conducting airways (the trachea, bronchi, intrapulmonary bronchi, bronchioles, and terminal bronchioles) terminate in respiratory airways (respiratory bronchioles and alveolar ducts) where gas exchange occurs. No JSRV SU-positive cells were found in the bronchi. Single JSRV SU-positive cells and clusters of JSRV SU-positive cells were found in bronchioles, terminal bronchioles, respiratory bronchioles, and the alveolar region (Fig. 3B to D). Epithelial cells lining these airways are known to include ciliated epithelial cells, Clara cells, neuroendocrine cells, neuroepithelial bodies (NEBs), and alveolar type I and type II pneumocytes (11).

FIG. 3.

Localization of JSRV SU-positive cells in OPA-E. (A) Location of single cells and clusters of cells expressing JSRV SU in 24 sections of lung tissue from 4 infected lambs at 10 days postinoculation. T, terminal; R, respiratory. (B) Respiratory bronchiole with three single cells expressing JSRV SU (10 days postinoculation). OM, ×400. (C) Alveolar region showing a small cluster of JSRV SU-positive cells (10 days postinoculation). OM, ×400. (D) Terminal bronchiole with a tumor cluster labeling with anti-JSRV SU antibody (72 days postinoculation). OM, ×600.

Proliferation potential of candidate JSRV target cells.

Most retroviruses require actively dividing cells for efficient integration and replication (10). Experiments on rodent lungs have indicated that Clara cells, NEBs, and type II pneumocytes are able to proliferate (28-29, 61). To confirm this in the ovine lung, expression of Ki-67 (a proliferation marker) was colocalized with phenotypic markers for these cell types (CCSP, synaptophysin, and SP-C) using IHC. Dual labeling of Ki-67 and each phenotypic marker was observed in the lungs of 16-day-old negative-control lambs (Fig. 4). This demonstrates the proliferative activity of Clara cells, NEBs, and type II pneumocytes in the lamb lung and, hence, their potential as target cells for JSRV. No significant differences in Ki-67-expression between mock-inoculated and noninoculated control groups were noted. Therefore, the intratracheal route of inoculation employed in these experiments did not influence the proliferation of potential target cells.

FIG. 4.

Determination of the proliferation potential of candidate JSRV target cells in 16-day-old negative-control lambs. Sections were incubated with anti-Ki-67 antibody, a proliferation marker, and one of three antibodies to label Clara cells, NEBs, or type II pneumocytes. (A) Bronchiolar epithelium labeled with anti-CCSP antibody (purple cytoplasmic stain) and anti-Ki-67 antibody (brown nuclear stain). One cell (arrow) shows dual labeling with both antibodies. OM, ×600. (B) Alveolar region labeled with anti-synaptophysin antibody (purple cytoplasmic stain) and anti-Ki-67 antibody (brown nuclear stain). Multiple cells show dual labeling with both of the antibodies (arrows). OM, ×400. (C) Alveolar region labeled with anti-SP-C antibody (red cytoplasmic stain) and anti-Ki-67 antibody (green nuclear stain). One cell shows dual labeling with both of the antibodies (arrow). Dark blue, DAPI-labeled nuclei. OM, ×400. These data confirm that Clara cells, NEBs, and type II pneumocytes are all capable of proliferating in the lung of lambs this age.

JSRV SU expression in single cells colocalizes with CCSP or SP-C.

In order to identify the phenotypes of individual cells targeted by JSRV, sections of lung tissue from lambs culled 10 days postinoculation were analyzed with immunofluorescence using antibodies to SP-C, CCSP, and synaptophysin. To ensure this analysis focused on single JSRV-positive cells only, serial sections were analyzed in groups of three. The first and third sections were labeled with JSRV SU, SP-C, and CCSP antibodies, while for the middle section, the SP-C antibody was replaced with the synaptophysin antibody. The aim of this approach was to identify the same cell expressing JSRV in serial sections and, thus, to determine the expression of all three phenotypic markers (SP-C, CCSP, and synaptophysin) for that cell. Additional validation of these antibodies is presented in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

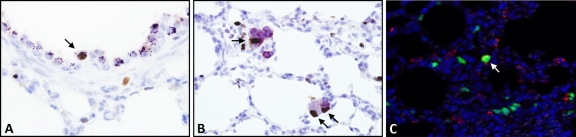

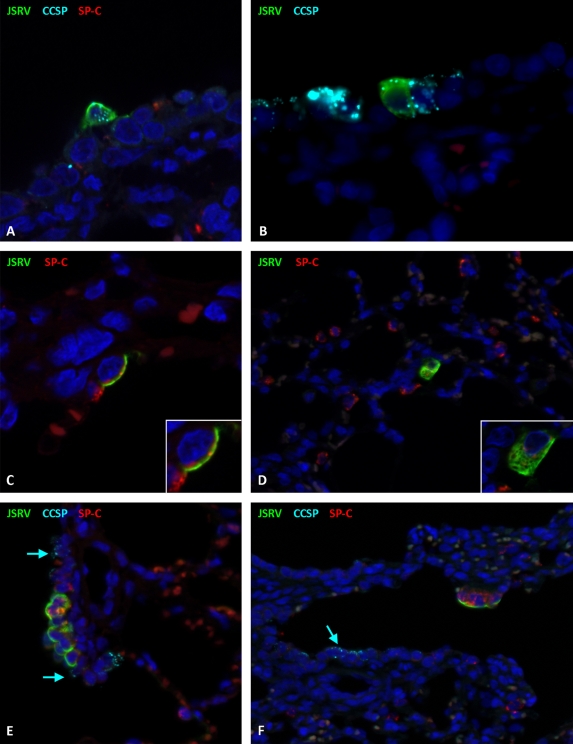

For each lamb, tissue obtained from 5 fixed sites was analyzed in this way, and a total of 13 single JSRV-positive cells were identified and characterized (Table 2). Of these cells, single JSRV-positive cells were found to label with anti-CCSP (5 of 13 analyzed) (Fig. 5A and B) or with anti-SP-C (2 of 11 analyzed). Only 1 cell (of 11 analyzed) was positive for both SPC and CCSP. While clearly present, SP-C labeling of single SU-positive cells at 10 days postinoculation was accompanied by a high background level and did not photograph well. However, additional examples of single SU/SP-C-positive cells were identified at 71 to 92 days postinoculation (Fig. 5C and D). Videos S1 to S3 in the supplemental material show Z-stacks of representative cells. No JSRV-positive cells that also labeled positively for synaptophysin were found (6 cells analyzed).

TABLE 2.

Protein expression of single SU-positive cells in lambs at 10 days postinoculation

| Lamb no. | Locationa | Markerb |

Figure | Z-stackc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SU | CCSP | SP-C | SYN | ||||

| 2852 | T bronchiole | Yes | No | No | No | 7A and B | Video S4 |

| 2854 | ADW | Yes | No | ND | No | ||

| 2854 | T bronchiole | Yes | Yes | No | ND | ||

| 2856 | R bronchiole | Yes | Yes | No | ND | 5A | Video S1 |

| 2856 | ADW | Yes | No | Yes | ND | ||

| 2856 | T bronchiole | Yes | Yes | Yes | ND | ||

| 2856 | ADW | Yes | No | No | ND | ||

| 2856 | R bronchiole | Yes | Yes | No | ND | ||

| 2858 | T bronchiole | Yes | No | No | No | ||

| 2858 | T bronchiole | Yes | No | No | No | ||

| 2858 | T bronchiole | Yes | Yes | No | No | 5B | |

| 2858 | R bronchiole | Yes | No | ND | No | ||

| 2858 | R bronchiole | Yes | No | No | ND | ||

T bronchiole, terminal bronchiole; R bronchiole, respiratory bronchiole; ADW, alveolar duct wall.

SYN, synaptophysin; ND, not determined. “Yes” or “No” denotes expression of protein or the lack thereof, respectively, as determined by immunofluorescence.

Videos of Z-stacks are presented in the supplemental material.

FIG. 5.

Phenotypes of single cells and clusters of cells expressing JSRV SU in OPA-E. (A) Respiratory bronchiole at 10 days postinoculation with a single cell colabeling with anti-JSRV SU antibody (in green) and anti-CCSP antibody (in light blue). The dark blue label is DAPI. Labeling for JSRV SU is on the cell surface, and that for CCSP is in the cell cytoplasm. OM, ×1,000. (B) Terminal bronchiole at 10 days postinoculation showing labeling for JSRV SU (in green) and CCSP (in light blue) in the same cell. OM, ×1,000. Note that the apparent diffuse pale red labeling is due to autofluorescence of erythrocytes. (C) The alveolar region at 72 days postinoculation shows a single cell labeling with anti-JSRV SU antibody (in green) and anti-SP-C antibody (in red). The inset demonstrates the different locations of these antigens, with JSRV SU on the cell surface and SP-C in the cytoplasm. OM, ×1,000. (D) Alveolar region at 72 days postinoculation showing colocalization of JSRV SU (in green) and SP-C (in red) to the same cell. Normal labeling of type II pneumocytes can be seen in the low-power view. OM, ×400. The inset allows better visualization of each antigen. (E) This section has been incubated with three antibodies, anti-JSRV SU (in green), anti-SP-C (in red), and anti-CCSP (in light blue). An early tumor cluster at 10 days postinoculation is shown growing from a section of the respiratory bronchiole and labels for JSRV SU (in green) and SP-C (in red) only. Normal labeling of Clara cells can be seen at the periphery of the nodule (arrows). OM, ×400. (F) An early cluster at 10 days postinoculation growing from a section of the respiratory bronchiole labels for JSRV SU (in green) and SP-C (in red) but not CCSP (in light blue). CCSP-positive Clara cells are labeled in the normal respiratory bronchiolar epithelium (arrow). OM, ×400.

Does JSRV infect ovine lung stem cells?

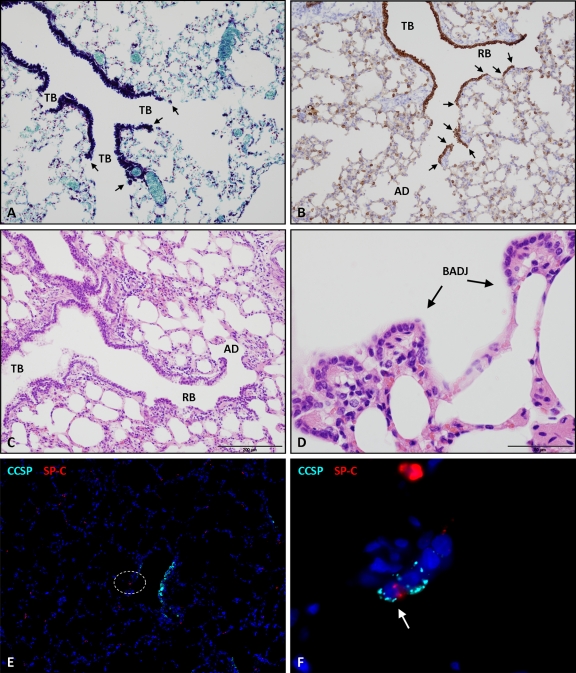

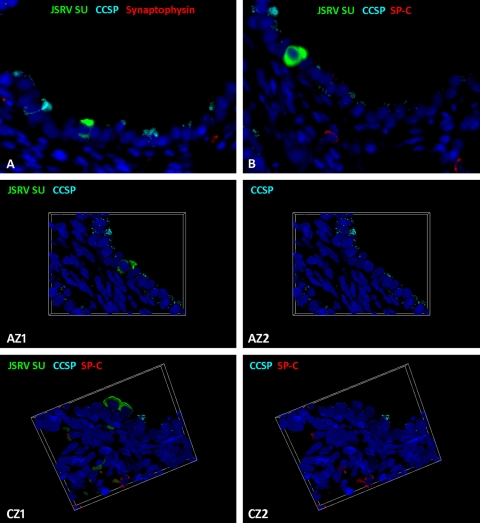

Stem cells in the ovine lung have yet to be characterized. In mice, injury models have identified a number of putative stem cells/progenitor cells in the lung (32, 37, 42). One of these types of cells, denoted BASCs, have been partly defined by the dual expression of CCSP and SP-C and by their specific anatomical location at the bronchioloalveolar duct junction (BADJ), where conducting and respiratory airways meet (Fig. 6A to D) (42). BASCs have been proposed as the cell of origin of adenocarcinoma in a K-ras model, and it was therefore of interest to determine whether they are infected by JSRV. For the purposes of the present study, the dual SP-C/CCSP-labeling phenotype was used as a marker for the ovine BASC equivalent. Of all the sections of lung examined, dual expression of SP-C and CCSP was found in only 1 cell at the BADJ (Fig. 6E and F). Another single cell was labeled with SP-C, CCSP, and JSRV SU, but this was located in a terminal bronchiole rather than at a BADJ, and consequently, no evidence of JSRV infection of BASCs in sheep was obtained. However, JSRV SU expression was detected in some cells which did not label with either SP-C or CCSP (5 of 11 cells analyzed) (Table 2; Fig. 7A and B). This was confirmed using optical sectioning by structured illumination to construct a Z-stack (Fig. 7, AZ1 and AZ2; see also Video S4 in the supplemental material) and was seen in single cells located in both terminal and respiratory bronchioles.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of mouse and sheep lung anatomies to determine the potential location of BASC-like cells in each species. (A) Mouse lung stained with Luxol fast blue, which highlights the terminal bronchiolar (TB) epithelium (in dark blue). There is an abrupt junction between these conducting airways and alveolar ducts, called the bronchioloalveolar duct junction (BADJ) (arrows). OM, ×400. This is where BASCs, which label with SP-C and CCSP, have been identified in mice (42). (B) Sheep lung incubated with anti-pan-cytokeratin antibody to label all bronchiolar epithelia (in brown) using IHC. The continuous terminal bronchial epithelium leads into respiratory bronchioles (RB) in the sheep. These consist of sections of bronchial epithelium interrupted by alveolar pockets capable of gas exchange. Respiratory bronchioles terminate in alveolar ducts (AD). As BADJs occur at each junction of bronchiolar and alveolar epithelia (arrows), the presence of respiratory bronchioles in the sheep increases the number of BADJs and therefore the number of potential niches for BASCs. OM, ×40. (C, D) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of normal sheep lung to highlight the anatomy of the terminal conducting and respiratory airways. (E and F) Sheep lung labeled with anti-SP-C (in red) and anti-CCSP antibodies. Dark blue, DAPI-labeled nuclei. (E) Low-power view, allowing orientation of the respiratory bronchiole. OM, ×100. (F) High-power view of the dotted area depicted in panel E, showing an ovine BASC (arrow), i.e., a dually labeled cell (SP-C and CCSP) at the BADJ. OM, ×1,000.

FIG. 7.

Cells expressing JSRV SU but not SP-C, CCSP, or synaptophysin. (A) Section of a terminal bronchiole at 10 days postinoculation showing a single cell labeling positively with anti-JSRV SU (in green) but not anti-CCSP (in light blue) or anti-synaptophysin (in red). Original magnification (OM), ×400. Dark blue, DAPI-labeled nuclei. (B) A serial section of the same terminal bronchiole depicted in panel A showing the same cell labeling positively for anti-JSRV SU (in green) but not for anti-CCSP (in light blue) or anti-SP-C (in red). OM, ×400. (AZ1 and AZ2) Compressed Z-stack images of the same cell shown in panel A with (AZ1) and without (AZ2) JSRV SU labeling. This shows that the single JSRV SU-positive cell does not express CCSP. OM, ×1,000. Video S4 in the supplemental material shows the complete Z-stack. (CZ1 and CZ2) Compressed Z-stack images with and without JSRV SU labeling. These show a respiratory bronchiole with two cells expressing JSRV SU (in green) that do not label with CCSP (in light blue) or SP-C (in red). OM, ×1,000. Video 5 in the supplemental material shows the complete Z-stack.

JSRV SU expression in cell clusters colocalizes with SP-C, synaptophysin, CCSP, or none of these markers.

In addition to single cells, the phenotypes of small clusters of JSRV-positive cells (2 to 20 cells in size) were also examined using immunofluorescence. Across the 20 sections, a total of 21 SU-positive clusters were analyzed (Table 3). Of these, 6 of 13 clusters also showed strong labeling with anti-SP-C (Fig. 5E and F). Occasional cells within these neoplastic clusters labeled weakly for synaptophysin (4 of 11 clusters analyzed) or CCSP (2 of 21 clusters). In addition, some JSRV SU-positive cell clusters did not label with anti-SP-C, anti-CCSP, or anti-synaptophysin antibodies. Figure 7, CZ1 and CZ2, and Video S5 in the supplemental material show examples of an SU-positive but SPC/CCSP-negative cluster. It was notable that, as for the single cells, JSRV-positive cell clusters were present in conducting and respiratory airways.

TABLE 3.

Protein expression of clusters of SU-positive cells in lambs at 10 days postinoculation

| Lamb no. | No. of cells in cluster | Locationa | Markerb |

Figure | Z-stackc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SU | CCSP | SP-C | SYN | |||||

| 2852 | 6 | R bronchiole | Yes | Yes—weak | Yes | ND | ||

| 2854 | 3 | Alveolar cells | Yes | No | ND | No | ||

| 2854 | 7 | T bronchiole | Yes | Yes—weak | ND | No | ||

| 2854 | 2 | R bronchiole | Yes | No | ND | Yes | ||

| 2854 | 2 | R bronchiole | Yes | No | No | ND | 7 CZ1 | Video S5 |

| 2854 | 3 | R bronchiole/ADW | Yes | No | ND | No | ||

| 2854 | 18 | R bronchiole/ADW | Yes | No | ND | Yes | ||

| 2854 | 4 | R bronchiole/alveoli | Yes | No | Yes | ND | ||

| 2854 | 2 | R bronchiole/alveoli | Yes | No | ND | No | ||

| 2854 | 2 | R bronchiole | Yes | No | No | ND | ||

| 2854 | 4 | R bronchiole | Yes | No | Yes | No | 5F | |

| 2856 | 4 | R bronchiole/ADW | Yes | No | No | Yes | ||

| 2856 | 2 | ADW | Yes | No | Yes | ND | ||

| 2856 | 5 | R bronchiole/ADW | Yes | No | ND | Yes | ||

| 2856 | 10 | ADW | Yes | No | Yes | ND | ||

| 2856 | 16 | ADW | Yes | No | No | ND | ||

| 2858 | 2 | R bronchiole | Yes | No | No | ND | ||

| 2858 | 20 | R bronchiole | Yes | No | Yes | ND | ||

| 2858 | 12 | R bronchiole/ADW | Yes | No | No | ND | ||

| 2858 | 3 | Bronchiole | Yes | No | No | No | ||

| 2858 | 4 | R bronchiole | Yes | No | ND | No | ||

T bronchiole, terminal bronchiole; R bronchiole, respiratory bronchiole; ADW, alveolar duct wall.

SYN, synaptophysin; ND, not determined. “Yes” or “No” denotes expression of protein or the lack thereof, respectively, as determined by immunofluorescence.

Videos of Z-stacks are presented in the supplemental material.

DISCUSSION

In this study, an experimental model of OPA was used to identify the target cells for JSRV infection and to explore the possibility that JSRV infects stem cells in the ovine lung. Single JSRV SU-positive cells were found to colabel with CCSP or SP-C but not with synaptophysin (Fig. 5A to D). This demonstrates that Clara cells and type II pneumocytes are target cells for JSRV infection in the lung. CCSP-positive cells were located in the bronchioles, terminal bronchioles, and respiratory bronchioles, and SP-C-positive cells were located in the alveolar region. In addition, undifferentiated JSRV SU-positive cells that did not label for any of these three phenotypic markers were observed in terminal and respiratory bronchioles (Fig. 7). It was not possible to identify significant numbers of SP-C/CCSP dual-positive BASC-like cells in control or infected lambs of any age. Only 1 cell triple labeled positively for JSRV SU, SP-C, and CCSP, but it was located in a terminal bronchiole, not at a BADJ. Although it was only possible to analyze a limited number of single JSRV-expressing cells due to their rare occurrence in the tissues studied, this is the first demonstration of individual JSRV-infected epithelial cells in the lung and the first to characterize the phenotypes of these target cells.

Early speculation regarding the cells of origin for OPA was based on the location of tumor nodules in natural field cases. These were identified as glandular epithelial cells arising from bronchi, bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveoli (14-15, 19, 86). Subsequent IHC studies demonstrated that viral antigen expression was limited to neoplastic tissue only (56, 73, 88). The majority of these cells expressed SP-C, and a few expressed CCSP (3, 64). A quantitative study of mature tumors found that, on average, SP-C-positive cells (82%) are the principal cell type, with CCSP-positive cells (7%) and undifferentiated cells (11%) making up the remainder (64).

The different phenotypes of single cells expressing JSRV detected in this study reflect the cellular heterogeneity of mature tumors. In addition, the observation that single cells and tumor clusters have similar anatomical locations is consistent with a model in which JSRV infection and expression by CCSP-positive, SP-C-positive, and undifferentiated cells leads to transformation of all these cell types and the development of tumor nodules. However, further evidence is required to prove this conclusively. Comparisons between immunofluorescence labeling of single cells (Table 2; Fig. 5A and B) and small clusters (Table 3; Fig. 5E and F) show that CCSP expression is commonly found in single JSRV SU-positive cells but rarely in clusters. The most likely explanation for this is that CCSP expression is downregulated following transformation by JSRV as cells proliferate. CCSP is thought to antagonize the neoplastic phenotype, and reduced expression has been found in mature tumors known to be of Clara cell origin (35, 44). Alternatively, infected CCSP-positive cells may lose JSRV expression, for example, through repression of the viral LTR. A further possibility is that CCSP-positive infected cells might die by apoptosis, although there is no morphological evidence of this on examination of histochemically stained sections.

Although SP-C and CCSP are recognized markers of type II pneumocytes and Clara cells, in the mouse, subpopulations of SP-C- and CCSP-positive cell types have been identified according to their progenitor potential (37, 79-80). For example, naphthalene resistant “variant Clara cells” are found in NEBs and at BADJs (37, 79-80). These cells express CCSP, but unlike classical Clara cells, they lack the cytochrome P450 enzymes that metabolize xenobiotics and induce naphthalene toxicity (76). Following injury, these cells are capable of repopulating the damaged epithelium by proliferating and differentiating into classical Clara cells and ciliated epithelial cells. Subpopulations of type II pneumocytes also vary in their response to injury (62-63, 68, 72, 75). For example, on exposure of rat SP-C-positive cells to hyperoxic conditions, E-cadherin-negative cells were identified that were resistant to damage, were more proliferative, and exhibited higher levels of telomerase activity than E-cadherin-positive cells (68). It was proposed that the E-cadherin-negative cells represented a transit-amplifying population of type II pneumocytes, which might be responsible for the repopulation and repair of the damaged epithelium (68). While the present study showed Ki-67 expression by Clara cells and type II pneumocytes and hence their proliferative capacity, additional work is required to determine whether functional subpopulations of Clara cells and type II pneumocytes exist in the sheep and, if so, whether they are preferentially infected and transformed by JSRV.

A proportion of the single cells expressing JSRV Env found in this study did not label positively for any of the three phenotypic markers tested (Table 2; Fig. 7). Several hypotheses can be made regarding the origin of this undifferentiated cell type. First, they could represent infected Clara cells which are in the process of dedifferentiation and transformation. As noted above, CCSP expression is commonly reduced during neoplastic transformation (44, 71). Second, these cells could be an example of an immature progenitor-type cell, as ciliated and Clara cells in the lungs of lambs of this age are still in the process of differentiating (H. M. Martineau and D. J. Griffiths, unpublished data). Third, these cells could be an example of an as-yet-undefined population of progenitor cells in the ovine lung. It is commonly recognized that stem cells have a less differentiated phenotype than their terminally differentiated counterparts (83). Interestingly, recent work with human lung cancer has used the membrane antigen CD133 to isolate a rare population of cells with stem cell properties from tumors (27). These cells also lacked the lineage-specific lung cell markers tested in the present study. It is uncertain whether such cells originate from an endogenous stem cell in the lung or if they have reacquired a self-renewal capacity and stem cell-like properties after later acquiring mutations (9). In the current study, efforts were made to optimize antibodies to label the potential stem cell proteins CD34, Oct-4, and CD133. However, the available antibodies, which were raised against mouse or human markers, did not positively label any of the ovine tissues tested (including fetal bone marrow, lung, and liver and adult liver tumor, lung tumor, bone marrow, testis, and pancreas) (data not shown).

The possibility that JSRV infects the ovine equivalent of a BASC was also addressed in this study. However, dual labeling using immunofluorescence failed to detect significant numbers of BASC-like cells in the sheep. In the mouse, BASCs have been found in 35% of BADJs, which occur at the junction of the terminal bronchioles and alveoli (42). In the sheep, the structure of the lung is different (65), and the presence of respiratory bronchioles effectively increases the number of BADJs and therefore the number of potential BASC niches compared to the numbers of those in mouse lung (Fig. 6A to D). However, only 2 cells were identified with convincing dual expression of CCSP and SP-C in all the sections examined from control and infected lambs of different ages (Fig. 6E and F). One of these also expressed JSRV SU but was located in a terminal bronchiole and not at a BADJ. This CCSP/SP-C dual-positive cell could be in the process of dedifferentiating following viral infection. The plasticity of mature cell types in the lung and their ability to dedifferentiate following appropriate stimuli has been demonstrated recently (43). Progenitor cells in the lung have also been shown to express multiple lineage markers during embryonic development in the mouse prior to more restricted protein expression in the more differentiated cell lineages (89). While it is still possible that JSRV might infect BASCs, the low numbers detected here suggest that the availability of BASC-like cells in the sheep does not have a large influence on JSRV infection. Interestingly, since this study began, experiments using transgenic lineage tracing and chimeric mouse models have questioned the validity of SPC/CCSP coexpression as a method for identifying cells with true stem cell properties in the mouse lung (31, 67, 80, 83). In addition, these studies have identified several other cell phenotypes that represent potential lung epithelial stem/progenitor cells (49, 82). Further investigations of these cells in sheep are limited until specific markers to identify stem cells in the ovine lung have been better defined.

The role of NEBs as target cells for JSRV was also investigated. In OPA-E, Ki-67-positive cells within NEBs were detected, but no single JSRV SU-positive cells colocalized with synaptophysin expression. However, clusters of synaptophysin-positive cells were seen within some tumors (Fig. 1H). It is uncertain whether these represent transdifferentiated tumor cells or whether the tumor has grown around existing NEBs. As NEBs are known to release growth factors during lung development (e.g., bombesin), it is possible that that this results in a localized increase in proliferation of potential target cells, facilitating JSRV infection and tumor development close to NEBs. No synaptophysin-positive cells were detected in cases of OPA-N. This is possibly a result of the larger tumor size in OPA-N than in OPA-E and, therefore, the reduced likelihood of sectioning through an NEB. Alternatively, neuroendocrine differentiation could be lost as tumors increase in size. Although traditionally found in small-cell carcinomas which originate from neuroepithelial cells, neuroendocrine differentiation has been recorded in human adenocarcinomas of the lung (39).

The data presented here provide evidence that JSRV can infect and express viral proteins in multiple cell types in the lung. For this to be possible, each cell type described must be capable of dividing and expressing cellular factors essential for JSRV replication, including a cell surface receptor and appropriate transcription factors. Circumstances that result in changes in proliferation or in expression of these factors may affect the susceptibility of the described target cells to JSRV infection. For example, the differentiation state of bronchial epithelial cells can affect receptor expression and permissivity for influenza A virus (7). In the mouse lung, changes in cell differentiation and proliferation have been described following lung injury (79), while in the sheep lung, variations in cell differentiation have been found during postnatal development (Martineau and Griffiths, unpublished data). Interestingly, an age-related susceptibility to experimental infection with JSRV has been reported (73), with lambs infected at a younger age developing clinical disease more quickly than older lambs inoculated with the same dose of virus. Proposed explanations for this include a reduction in the number of Clara cells and type II pneumocytes as animals mature and a reduction in the proliferation rate of target cells (73). The discovery that JSRV also infects undifferentiated cells in the respiratory tract may provide an additional explanation for this age-related change in susceptibility. It is notable that although some viral infections cause more severe disease in young animals than in older animals due to the immaturity of the neonatal immune system, this appears to be an unlikely explanation for the age-related susceptibility of sheep to JSRV, as infected animals do not develop significant acquired immunity to the virus at any age (54, 81).

In addition to improving the understanding of JSRV pathogenesis, this experimental model of OPA provides a unique tool with which to study the early stages of transformation in single cells in the lung. Examination of the early stages of lung cancer in humans is difficult, as clinical signs only develop once the disease is at an advanced stage. Although murine transgenic and carcinogen-induced models of lung cancer are useful, limitations of rapid growth and asynchronicity in tumor development have been reported (40). OPA is a slow-growing tumor that is easily inducible. As shown here, it is now possible to detect single transformed cells in vivo. The findings of this study provide a basis for future work investigating the progression from initial infection to tumor development and enhance the relevance of OPA as a model for human lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Scottish Government Rural and Environment Research and Analysis Directorate (funded through RERAD Programme 2 for Profitable and Sustainable Agriculture) and by a Moredun Foundation Studentship awarded to H.M.M.

We thank Clare Underwood, Val Forbes, Jeanie Finlayson, Stephen Maley, and Alex Schock for assistance with sample processing and interpretation of IHC; Jeremy Brown, Mark Montgomery, and David Kelly for advice on fluorescence microscopy; Alex Nunez (Veterinary Laboratories Agency) for providing the sample of the non-OPA lung tumor; Leenadevi Thonur, Joanne Crawford, and Patricia Dewar for help with postmortems, and the staff of the Moredun Research Institute Clinical Division for excellent animal care. We are grateful to Dusty Miller, Claudio Murgia, Jeffrey Whitsett, and Angela Keiser for providing essential reagents and to the farmers who support our work through donation of natural cases of OPA.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 January 2011.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archer, F., et al. 2007. Alveolar type II cells isolated from pulmonary adenocarcinoma: a model for JSRV expression in vitro. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 36:534-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnaud, F., et al. 2007. A paradigm for virus-host coevolution: sequential counter-adaptations between endogenous and exogenous retroviruses. PLoS Pathog. 3:e170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beytut, E., M. Sozmen, and S. Erginsoy. 2009. Immunohistochemical detection of pulmonary surfactant proteins and retroviral antigens in the lungs of sheep with pulmonary adenomatosis. J. Comp. Pathol. 140:43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonné, C. 1939. Morphological resemblance of pulmonary adenomatosis (Jaagsiekte) in sheep and certain cases of cancer of the lung in man. Am. J. Cancer 34:491-501. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caporale, M., et al. 2005. Infection of lung epithelial cells and induction of pulmonary adenocarcinoma is not the most common outcome of naturally occurring JSRV infection during the commercial lifespan of sheep. Virology 338:144-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caporale, M., et al. 2006. Expression of the Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus envelope glycoprotein is sufficient to induce lung tumors in sheep. J. Virol. 80:8030-8037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, R. W., et al. 2010. Influenza H5N1 and H1N1 virus replication and innate immune responses in bronchial epithelial cells are influenced by the state of differentiation. PLoS One 5:e8713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chitra, E., et al. 2009. Generation and characterization of JSRV envelope transgenic mice in FVB background. Virology 393:120-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke, M. F., et al. 2006. Cancer stem cells-perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR Workshop on cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 66:9339-9344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coffin, J. M., S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.). 1997. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [PubMed]

- 11.Corrin, B. 2000. Pathology of the lungs. Hardcourt Publishers Ltd., London, United Kingdom.

- 12.Cousens, C., et al. 2007. In vivo tumorigenesis by Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus (JSRV) requires Y590 in Env TM, but not full-length orfX open reading frame. Virology 367:413-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cousens, C., et al. 2009. Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus is present at high concentration in lung fluid produced by ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma-affected sheep and can survive for several weeks at ambient temperatures. Res. Vet. Sci. 87:154-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowdry, E. V. 1925. Studies on the etiology of Jagziekte. II. Origin of the epithelial proliferations, and the subsequent changes. J. Exp. Med. 42:335-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuba-Caparo, A., E. de la Vega, and M. Copaira. 1961. Pulmonary adenomatosis of sheep-metastasizing bronchiolar tumors. Am. J. Vet. Res. 22:673-682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dakessian, R. M., and H. Fan. 2008. Specific in vivo expression in type II pneumocytes of the Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus long terminal repeat in transgenic mice. Virology 372:398-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dakessian, R. M., Y. Inoshima, and H. Fan. 2007. Tumors in mice transgenic for the envelope protein of Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus. Virus Genes 35:73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danilkovitch-Miagkova, A., et al. 2003. Hyaluronidase 2 negatively regulates RON receptor tyrosine kinase and mediates transformation of epithelial cells by Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:4580-4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Kock, G. 1958. The transformation of the lining of the pulmonary alveoli with special reference to adenomatosis in the lungs (Jagziekte) of sheep. Am. J. Vet. Res. 19:261-269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De las Heras, M., et al. 2000. Evidence for a protein related immunologically to the Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus in some human lung tumours. Eur. Respir. J. 16:330-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De las Heras, M., L. Gonzalez, and J. M. Sharp. 2003. Pathology of ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 275:25-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De las Heras, M., et al. 2007. Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus is not detected in human lung adenocarcinomas expressing antigens related to the Gag polyprotein of betaretroviruses. Cancer Lett. 258:22-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeMartini, J. C., R. H. Rosadio, and M. D. Lairmore. 1988. The etiology and pathogenesis of ovine pulmonary carcinoma (sheep pulmonary adenomatosis). Vet. Microbiol. 17:219-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dungal, N. 1946. Experiments with Jaagsiekte. Am. J. Pathol. 22:737-759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunlap, K. A., M. Palmarini, and T. E. Spencer. 2006. Ovine endogenous betaretroviruses (enJSRVs) and placental morphogenesis. Placenta 27(Suppl. A):S135-S140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eramo, A., T. L. Haas, and R. De Maria. 2010. Lung cancer stem cells: tools and targets to fight lung cancer. Oncogene 29:4625-4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eramo, A., et al. 2008. Identification and expansion of the tumorigenic lung cancer stem cell population. Cell Death. Differ. 15:504-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans, M. J., L. J. Cabral-Anderson, and G. Freeman. 1978. Role of the Clara cell in renewal of the bronchiolar epithelium. Lab. Invest. 38:648-653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans, M. J., L. J. Cabral, R. J. Stephens, and G. Freeman. 1973. Renewal of alveolar epithelium in the rat following exposure to NO2. Am. J. Pathol. 70:175-198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan, H. 2003. Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus and lung cancer. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 31.Giangreco, A., et al. 2009. Stem cells are dispensable for lung homeostasis but restore airways after injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:9286-9291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giangreco, A., S. D. Reynolds, and B. R. Stripp. 2002. Terminal bronchioles harbor a unique airway stem cell population that localizes to the bronchoalveolar duct junction. Am. J. Pathol. 161:173-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gould, V. E., et al. 1986. Synaptophysin: a novel marker for neurons, certain neuroendocrine cells, and their neoplasms. Hum. Pathol. 17:979-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffiths, D. J., H. M. Martineau, and C. Cousens. 2010. Pathology and pathogenesis of ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma. J. Comp. Pathol. 142:260-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hicks, S. M., et al. 2003. Immunohistochemical analysis of Clara cell secretory protein expression in a transgenic model of mouse lung carcinogenesis. Toxicology 187:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hofacre, A., and H. Fan. 2004. Multiple domains of the Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus envelope protein are required for transformation of rodent fibroblasts. J. Virol. 78:10479-10489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong, K. U., S. D. Reynolds, A. Giangreco, C. M. Hurley, and B. R. Stripp. 2001. Clara cell secretory protein-expressing cells of the airway neuroepithelial body microenvironment include a label-retaining subset and are critical for epithelial renewal after progenitor cell depletion. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 24:671-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hopwood, P., et al. 2010. Absence of markers of betaretrovirus infection in human pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 41:1631-1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ionescu, D. N., et al. 2007. Nonsmall cell lung carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation-an entity of no clinical or prognostic significance. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 31:26-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson, E. L., et al. 2001. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 15:3243-3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jassim, F. A., J. M. Sharp, and P. D. Marinello. 1987. Three-step procedure for isolation of epithelial cells from the lungs of sheep with jaagsiekte. Res. Vet. Sci. 43:407-409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim, C. F., et al. 2005. Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell 121:823-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lange, A. W., A. R. Keiser, J. M. Wells, A. M. Zorn, and J. A. Whitsett. 2009. Sox17 promotes cell cycle progression and inhibits TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling to initiate progenitor cell behavior in the respiratory epithelium. PLoS One 4:e5711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linnoila, R. I., et al. 2000. The role of CC10 in pulmonary carcinogenesis: from a marker to tumor suppression. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 923:249-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu, S. L., and A. D. Miller. 2007. Oncogenic transformation by the jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus envelope protein. Oncogene 26:789-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maeda, N., M. Palmarini, C. Murgia, and H. Fan. 2001. Direct transformation of rodent fibroblasts by jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:4449-4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matiasek, L. A., et al. 2009. Ki-67 and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in intracranial meningiomas in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 23:146-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGee-Estrada, K., and H. Fan. 2007. Comparison of LTR enhancer elements in sheep beta retroviruses: insights into the basis for tissue-specific expression. Virus Genes 35:303-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McQualter, J. L., K. Yuen, B. Williams, and I. Bertoncello. 2010. Evidence of an epithelial stem/progenitor cell hierarchy in the adult mouse lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:1414-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller, A. D. 2008. Hyaluronidase 2 and its intriguing role as a cell-entry receptor for oncogenic sheep retroviruses. Semin. Cancer Biol. 18:296-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mornex, J. F., F. Thivolet, M. De las Heras, and C. Leroux. 2003. Pathology of human bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and its relationship to the ovine disease. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 275:225-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mura, M., et al. 2004. Late viral interference induced by transdominant Gag of an endogenous retrovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:11117-11122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neil, S., and P. Bieniasz. 2009. Human immunodeficiency virus, restriction factors, and interferon. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 29:569-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ortin, A., et al. 1998. Lack of a specific immune response against a recombinant capsid protein of Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus in sheep and goats naturally affected by enzootic nasal tumour or sheep pulmonary adenomatosis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 61:229-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palmarini, M., S. Datta, R. Omid, C. Murgia, and H. Fan. 2000. The long terminal repeat of Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus is preferentially active in differentiated epithelial cells of the lungs. J. Virol. 74:5776-5787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palmarini, M., et al. 1995. Epithelial tumour cells in the lungs of sheep with pulmonary adenomatosis are major sites of replication for Jaagsiekte retrovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 76:2731-2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palmarini, M., and H. Fan. 2001. Retrovirus-induced ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma, an animal model for lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 93:1603-1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palmarini, M., et al. 2001. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase docking site in the cytoplasmic tail of the Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus transmembrane protein is essential for envelope-induced transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. J. Virol. 75:11002-11009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palmarini, M., M. Mura, and T. E. Spencer. 2004. Endogenous betaretroviruses of sheep: teaching new lessons in retroviral interference and adaptation. J. Gen. Virol. 85:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palmarini, M., J. M. Sharp, M. de las Heras, and H. Fan. 1999. Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus is necessary and sufficient to induce a contagious lung cancer in sheep. J. Virol. 73:6964-6972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peake, J. L., S. D. Reynolds, B. R. Stripp, K. E. Stephens, and K. E. Pinkerton. 2000. Alteration of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells during epithelial repair of naphthalene-induced airway injury. Am. J. Pathol. 156:279-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peers, C., P. J. Kemp, C. A. Boyd, and P. C. Nye. 1990. Whole-cell K+ currents in type II pneumocytes freshly isolated from rat lung: pharmacological evidence for two subpopulations of cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1052:113-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perl, A. K., et al. 2005. Conditional recombination reveals distinct subsets of epithelial cells in trachea, bronchi, and alveoli. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 33:455-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Platt, J. A., N. Kraipowich, F. Villafane, and J. C. DeMartini. 2002. Alveolar type II cells expressing jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus capsid protein and surfactant proteins are the predominant neoplastic cell type in ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Vet. Pathol. 39:341-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Plopper, C. G., A. T. Mariassy, and L. O. Lollini. 1983. Structure as revealed by airway dissection. A comparison of mammalian lungs. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 128:S4-S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rai, S. K., et al. 2001. Candidate tumor suppressor HYAL2 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored cell-surface receptor for jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus, the envelope protein of which mediates oncogenic transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:4443-4448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rawlins, E. L., et al. 2009. The role of Scgb1a1+ Clara cells in the long-term maintenance and repair of lung airway, but not alveolar, epithelium. Cell Stem Cell 4:525-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reddy, R., et al. 2004. Isolation of a putative progenitor subpopulation of alveolar epithelial type 2 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 286:L658-L667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reya, T., S. J. Morrison, M. F. Clarke, and I. L. Weissman. 2001. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 414:105-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reynolds, S. D., et al. 2000. Conditional Clara cell ablation reveals a self-renewing progenitor function of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 278:L1256-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reynolds, S. D., and A. M. Malkinson. 2010. Clara cell: progenitor for the bronchiolar epithelium. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42:1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roper, J. M., R. J. Staversky, J. N. Finkelstein, P. C. Keng, and M. A. O'Reilly. 2003. Identification and isolation of mouse type II cells on the basis of intrinsic expression of enhanced green fluorescent protein. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 285:L691-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Salvatori, D., L. Gonzalez, P. Dewar, C. Cousens, M. de las Heras, R. G. Dalziel, and J. M. Sharp. 2004. Successful induction of ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma in lambs of different ages and detection of viraemia during the preclinical period. J. Gen. Virol. 85:3319-3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharp, J. M., and J. C. DeMartini. 2003. Natural History of JSRV in sheep. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 275:55-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sigurdson, S. L., and J. S. Lwebuga-Mukasa. 1998. Adhesive characteristics of type II pneumocyte subpopulations from saline-and silica-treated rats. Exp. Lung Res. 24:307-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singh, G., and S. L. Katyal. 2000. Clara cell proteins. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 923:43-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Soler-Federsppiel, B. S., P. Cras, J. Gheuens, D. Andries, and A. Lowenthal. 1987. Human gamma gamma-enolase: two-site immunoradiometric assay with a single monoclonal antibody. J. Neurochem. 48:22-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Spencer, T. E., M. Mura, C. A. Gray, P. J. Griebel, and M. Palmarini. 2003. Receptor usage and fetal expression of ovine endogenous betaretroviruses: implications for coevolution of endogenous and exogenous retroviruses. J. Virol. 77:749-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stripp, B. R., K. Maxson, R. Mera, and G. Singh. 1995. Plasticity of airway cell proliferation and gene expression after acute naphthalene injury. Am. J. Physiol. 269:L791-L799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stripp, B. R., and S. D. Reynolds. 2008. Maintenance and repair of the bronchiolar epithelium. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 5:328-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Summers, C., et al. 2002. Systemic immune responses following infection with Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus and in the terminal stages of ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1753-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Teisanu, R. M., et al. 23 July 2010. Functional analysis of two distinct bronchiolar progenitors during lung injury and repair.Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0098OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Teisanu, R. M., E. Lagasse, J. F. Whitesides, and B. R. Stripp. 2009. Prospective isolation of bronchiolar stem cells based upon immunophenotypic and autofluorescence characteristics. Stem Cells 27:612-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tyler, W. S. 1983. Comparative subgross anatomy of lungs. Pleuras, interlobular septa, and distal airways. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 128:S32-S36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Visvader, J. E., and G. J. Lindeman. 2008. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8:755-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wandera, J. G. 1968. Experimental transmission of sheep pulmonary adenomatosis (Jaagsiekte). Vet. Rec. 83:478-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wootton, S. K., C. L. Halbert, and A. D. Miller. 2005. Sheep retrovirus structural protein induces lung tumours. Nature 434:904-907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wootton, S. K., et al. 2006. Lung cancer induced in mice by the envelope protein of jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus (JSRV) closely resembles lung cancer in sheep infected with JSRV. Retrovirology 3:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wuenschell, C. W., et al. 1996. Embryonic mouse lung epithelial progenitor cells coexpress immunohistochemical markers of diverse mature cell lineages. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 44:113-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.