Abstract

The hemagglutinins (HAs) of human H1 and H3 influenza viruses and avian H5 influenza virus were produced as recombinant fusion proteins with the human immunoglobulin Fc domain. Recombinant HA-human immunoglobulin Fc domain (HA-HuFc) proteins were secreted from baculovirus-infected insect cells as glycosylated oligomer HAs of the anticipated molecular mass, agglutinated red blood cells, were purified on protein A, and were used to immunize mice in the absence of adjuvant. Immunogenicity was demonstrated for all subtypes, with the serum samples demonstrating subtype-specific hemagglutination inhibition, epitope specificity similar to that seen with virus infection, and neutralization. HuFc-tagged HAs are potential candidates for gene-to-vaccine approaches to influenza vaccination.

The need for a rapid and scalable vaccine response to emerging influenza virus strains is widely recognized (31). Traditional vaccines are largely based on whole virus, where the isolation of suitable seed strains, the supply of sufficient fertilized hen's eggs or cell culture, and the requirement for a robust immune response in the most at-risk populations all impinge on the productivity and speed of response that can be achieved (17, 29). Direct expression of the major vaccine antigen, the virion surface hemagglutinin (HA) protein, in insect cells can improve the speed and flexibility of therapeutic responses (6), but the immunogenicity of the product is often low, necessitating large doses of vaccine to generate a level of seroconversion consistent with protection (8, 15, 30). Oligomeric rather than monomeric HA was shown recently to be an improved immunogen (35), but oligomerization was ensured through the addition of an extraneous sequence of unknown risk for human immunization. Improving the immunogenicity of the HA with an immune-silent tag could be compatible with vaccine design if it could be shown that it would not compromise HA performance and would be consistent with rapid and high-level expression. Glycoproteins tagged with the human immunoglobulin Fc domain (HuFc) have been shown to have enhanced immunogenicity as a result of an increased half-life (26, 39) or Fc receptor-mediated uptake by antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells (5, 21, 23) or both. We have investigated the potential of HA-HuFc fusion proteins as influenza vaccine candidates and addressed whether (i) HuFc tagging was demonstrable for several HA subtypes, (ii) the resulting fusion proteins were immunogenic in the absence of additional adjuvant, (iii) the serum response was neutralizing, and (iv) the serum response was typical of that obtained following influenza immunization.

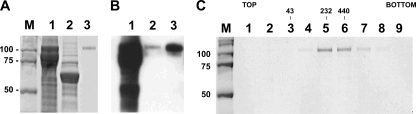

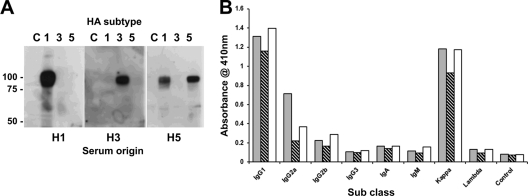

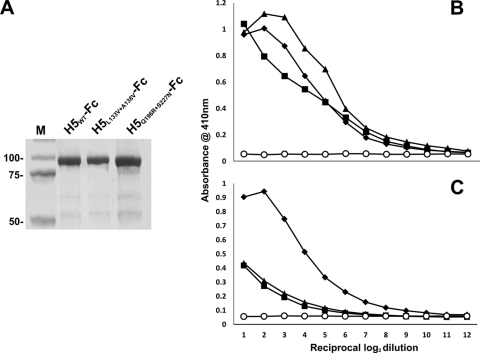

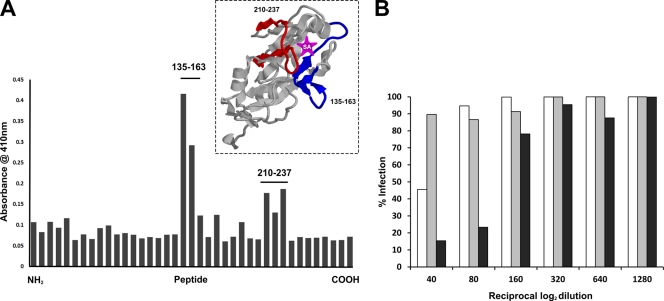

A unified cloning strategy was adopted for all the HA subtypes selected for expression. Baculovirus transfer vectors contained a well-cleaved signal peptide derived from the baculovirus gp64 major surface glycoprotein and the human Fc domain flanking directional genomic restriction sites for high-throughout baculovirus expression as described elsewhere (22, 38). Other studies have shown this expression strategy to be robust and widely applicable (2, 3, 5, 20). The HA sequences used were derived from influenza viruses A/New York/221/03 (a prepandemic seasonal human H1 subtype), A/Panama/2007/99 (a widely used human H3 subtype), and A/Vietnam/1194/04 (the widely distributed and occasionally zoonotic avian H5 subtype). The sequence representing the mature external domain of each HA was amplified from available clones or synthesized de novo from the deposited database sequence. Following the construction of the transfer vectors, recombinant baculoviruses were produced as described previously (40), and the expression and secretion of HuFc-tagged HA were confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot analysis of cells and supernatant at 2 days postinfection (Fig. 1 A). HA-HuFC fusion protein present in the supernatant was concentrated by lectin (lens culnaris) chromatography and purified by chromatography on immobilized protein A. Yields were typically 2 to 5 mg/liter (∼109 cells), and the product was essentially pure (Fig. 1B). Gel filtration chromatography and velocity gradient analysis revealed oligomeric structures ranging from dimers to hexamers (Fig. 1C). There was negligible aggregate apparent in the void volume or at the bottom of the gradients (Fig. 1C, fraction 9), and the product was endotoxin free (7). Purified HA-HuFc fusion protein (10 μg per dose) was used to immunize mice (n = 3) subcutaneously at 2-week intervals in the absence of adjuvant (for three inoculations in all), and the serum samples were collected after a further 2 weeks. Serotype-specific responses, assayed using nontagged HA, were observed for H1 and H3 subtypes by both enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blot analysis, but the H5 sera, while reacting most strongly to the cognate antigen, also bound well to the H1 HA (Fig. 2 A). Cross-reaction between H5 antibodies and H1 HA, including neutralizing antibodies, has been previously described elsewhere (12) and is probably related to the structures of the H5 and H1 HA1 domains being closely related (27). Interestingly, cross-reaction was not reciprocal (Fig. 2A), plausibly as a result of glycan shielding of H5 (34). All three HA subtypes were immunogenic, with no evidence of the poor immunogenicity attributed to attenuated H5 vaccines (17, 34). A dose-ranging study showed significant seroconversion (down to 100 ng per dose) with the same immunization regimen, a human equivalent dose of 24 μg as calculated by body surface area (24), lower than that observed for nontagged HA (30). Hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assays performed with guinea pig or turkey red blood cells, which contain a mixture of α2,6- and α2,3-linked sialic acids, gave titers of 1/200 and 1/100 for the H3 and H5 sera, respectively. The H1 protein agglutinated poorly, and 50% HAI was unobtainable. Cross-subtype HAI was not observed. Isotyping showed the responses to be predominantly composed of IgG1, with some IgG2a and IgG2b (Fig. 2B), and a Th2 response with some Th1 contribution, which is consistent with a result reported previously for soluble oligomeric HA (4, 35). We found only kappa light-chain use. To assess whether the polyvalent serum responses to soluble HA-HuFc immunogens were focused on the receptor binding domain of HA as seen in experimental infection studies (10), we immunized mice with further H5-Fc fusion proteins bearing mutations L133V plus A138V or Q196R plus S227N (Fig. 3 A). These mutations alter receptor specificity and affinity in synthetic glycan-based assays (1, 36, 37) and can be likened to those of influenza strains with altered SA affinities and preferences that arise following virus passage in the presence of an antibody response generated in response to the parental HA (10, 16). The overall immunogenicity of the sera obtained from each immunization was not significantly affected by the introduced amino acid changes, as shown by the ELISA titers determined with HA-HuFc (Fig. 3B). However, when the normalized sera were subjected to titration using wild-type H5 HA lacking the Fc tag, the sera generated with the H5 HAs containing either L133V plus A138V or Q196R plus S227N demonstrated significantly reduced titers compared to the sera generated with the wild-type H5 HA (Fig. 3C). The predominant antibody response to HA-HuFc fusion proteins is therefore to the HA1 domain and, in particular, to the receptor binding site whose conformation is altered by the introduced mutations. To further confirm that the epitope specificity of the polyvalent response to soluble HA-HuFc fusion protein resided in the HA1 domain, the serum samples generated with wild-type H5-HuFc were assayed for linear epitope recognition with a set of overlapping peptides (20-mers overlapping by 10 residues) made with the A/Vietnam/1194/04 HA sequence. Reactivity was limited to discrete peptides located at the top of the HA1 domain (Fig. 4 A), which broadly correlated with the epitope map for the H5 HA of A/Vietnam/1203/04, as determined by investigation of virus escape mutants (13), or the HA of A/Hong Kong/482/97, as determined by an antigen display library approach (18). The neutralizing activity of each serum sample was assessed by an entry inhibition assay using luciferase-encoding lentivirus vectors pseudotyped by H5 HA (28). Neutralization induced by the sera generated with the wild-type H5 sequence had an endpoint titer of ∼320, whereas neither of the serum samples generated with the mutant HAs had appreciable activity, although the serum samples generated with H5 Q196R plus S227N had marginal activity at the highest dose (Fig. 4B). Thus, fusion of HA at the C terminus to HuFc allows rapid purification of a conformationally relevant molecule that is immunogenic without the presence of added adjuvant and induces serum responses to the HA1 domain that are neutralizing, at least for the H5 HA studied here.

FIG. 1.

Expression and characterization of HA-HuFc fusion proteins. (A) Baculovirus-expressed HA-HuFc was present in cell extracts (track 1) and in supernatant (track 2) and following purification (track 3). (B) Western blot analysis performed with an anti-Hu Ig conjugate showed intermediates present in cell extracts but no evidence of breakdown in the supernatant or following purification. (Tracks are as described for panel A.) (C) Velocity gradient analysis of purified HA-HuFc showed a distribution of solution molecular masses estimated to range from dimers (∼200 kDa) to hexamers (∼600 kDa). No aggregate was present in the heavier fractions. Numbers to the left in panels A and C represent molecular mass markers, with values in kilodaltons. The numbers at the top of panel C represent solution molecular mass makers taken from a parallel gradient analysis, with values in kilodaltons. Panels A and C show stained 10% SDS-PAGE gels, and panel B shows chemiluminescence. Data shown are representative of the H3 subtype and are typical of other HA subtypes.

FIG. 2.

Serum responses to HA-HuFc fusion proteins. (A) Sera from mice immunized with H1, H3, and H5 HA-HuFc proteins were used at a 1:1,000 dilution for Western blot analysis of H1, H3, and H5 HA proteins lacking the Fc tag after separation by 10% SDS-PAGE. Track C, control insect cell extract; track 1, H1 HA; track 3, H3 HA; track 5, H5 HA. Numbers to the left of the panel represent molecular mass markers, with values in kilodaltons. (B) Isotyping of the serum responses to each immunogen. Gray bar, H1; bar with diagonal stripes, H3; clear bar, H5.

FIG. 3.

Expression, purification, and immunization of H5-HuFc-based receptor binding site mutants. (A) Wild-type (WT) H5 or H5 bearing two site-directed changes as shown was expressed and purified as described in the text. Mutant yields and stability were unaltered compared to parental H5 results. The results determined by 10% SDS-PAGE analysis of the stained final purified materials are shown. Numbers to the left of the panel represent molecular mass markers (track M), with values in kilodaltons. (B) Titration of polyvalent sera by ELISA using H5-Fc. (C) Titration of polyvalent sera by ELISA using wild-type H5 lacking the Fc tag after normalization of the titer as described for panel A. In both panels, the serum sample results are depicted as follows: ⧫, H5 wild type; ▪, H5 L133V plus A138V; ▴, H5 Q196R plus S227N; and ○, normal mouse serum. The assay was done in duplicate, and the averages of the results are plotted. Duplicate data points in the assays did not differ by more than 5%.

FIG. 4.

Epitope mapping and neutralization titers of the serum response to H5-HuFc. (A) Polyclonal sera were assayed by ELISA using immobilized peptides (biotinylated peptides absorbed to streptavidin-coated plates) spanning the HA1 domain of H5 HA. Individual mouse H5 sera gave the same profiles. Mutant sera failed to give a significant reaction. Inset: the reactive peptides from the pepscan displayed on the HA1 domain of the H5 structure. The location of the sialic binding site is indicated (SA). (B) Serum neutralization data measured by an entry inhibition assay of a lentivirus vector pseudotyped with wild-type H5 from strain A/Vietnam/1194/04. Clear bar, H5 Q196R plus S227N; gray bar, H5 L133V plus A138V; black bar, H5 wild type. The data represent averages of the results of duplicate assays.

A number of recombinant routes to influenza vaccination have demonstrated proof of principle (6, 11, 14). Unmodified recombinant HA may require high doses to ensure a protective response, limiting the opportunity for antigen sparing during periods of high demand, while the more immunogenic candidates, such as virus-like particles (VLP), are complex immunogens that have associated issues with respect to manufacturing yield. Our data suggest that a simple tagged recombinant form of HA can serve as an effective immunogen; equivalent constructs for H7, H9, and swine virus H1 have been found also to be equally immunogenic (not shown). Immunization with oligomeric HA was shown recently to provide protective immunity (35), but that study used a tag of uncertain clinical acceptance. HuFc-tagged therapeutic vaccines are in current clinical use (19), and their use is growing (25). Thus, HA-HuFc could be clinically acceptable, particularly for members of groups such as the elderly, who respond poorly to current vaccines (9). HuFc-mediated presentation of HA sequences capable of generating cross-protective responses (32, 33) would be particularly interesting.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Pamela Rummings for excellence in serum provision.

The work was supported by the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 December 2010.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auewarakul, P., et al. 2007. An avian influenza H5N1 virus that binds to a human-type receptor. J. Virol. 81:9950-9955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayora-Talavera, G., et al. 2009. Mutations in H5N1 influenza virus hemagglutinin that confer binding to human tracheal airway epithelium. PLoS One 4:e7836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barclay, W. S., et al. 2007. Probing the receptor interactions of an H5 avian influenza virus using a baculovirus expression system and functionalised poly(acrylic acid) ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 15:4038-4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bright, R. A., et al. 2007. Influenza virus-like particles elicit broader immune responses than whole virion inactivated influenza virus or recombinant hemagglutinin. Vaccine 25:3871-3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, H., X. Xu, and I. M. Jones. 2007. Immunogenicity of the outer domain of a HIV-1 clade C gp120. Retrovirology 4:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox, M. M. 2008. Progress on baculovirus-derived influenza vaccines. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 10:56-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox, M. M., and D. Karl Anderson. 2007. Production of a novel influenza vaccine using insect cells: protection against drifted strains. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses 1:35-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox, M. M., P. A. Patriarca, and J. Treanor. 2008. FluBlok, a recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses 2:211-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fichera, E., D. Felnerova, R. Mischler, J. F. Viret, and R. Glueck. 2009. New strategies to overcome the drawbacks of currently available flu vaccines. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 655:243-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hensley, S. E., et al. 2009. Hemagglutinin receptor binding avidity drives influenza A virus antigenic drift. Science 326:734-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang, S. M., P. Pushko, R. A. Bright, G. Smith, and R. W. Compans. 2009. Influenza virus-like particles as pandemic vaccines. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 333:269-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kashyap, A. K., et al. 2008. Combinatorial antibody libraries from survivors of the Turkish H5N1 avian influenza outbreak reveal virus neutralization strategies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:5986-5991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaverin, N. V., et al. 2007. Epitope mapping of the hemagglutinin molecule of a highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus by using monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 81:12911-12917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopecky-Bromberg, S. A., and P. Palese. 2009. Recombinant vectors as influenza vaccines. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 333:243-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakey, D. L., et al. 1996. Recombinant baculovirus influenza A hemagglutinin vaccines are well tolerated and immunogenic in healthy adults. J. Infect. Dis. 174:838-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambkin, R., L. McLain, S. E. Jones, S. L. Aldridge, and N. J. Dimmock. 1994. Neutralization escape mutants of type A influenza virus are readily selected by antisera from mice immunized with whole virus: a possible mechanism for antigenic drift. J. Gen. Virol. 75(Pt. 12):3493-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leroux-Roels, I., et al. 2007. Antigen sparing and cross-reactive immunity with an adjuvanted rH5N1 prototype pandemic influenza vaccine: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 370:580-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, J., et al. 2009. Fine antigenic variation within H5N1 influenza virus hemagglutinin's antigenic sites defined by yeast cell surface display. Eur. J. Immunol. 39:3498-3510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Licastro, F., M. Chiappelli, M. Ianni, and E. Porcellini. 2009. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists: differential clinical effects by different biotechnological molecules. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 22:567-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathewson, A. C., et al. 2008. Interaction of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus and NL63 coronavirus spike proteins with angiotensin converting enzyme-2. J. Gen. Virol. 89:2741-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metheringham, R. L., et al. 2009. Antibodies designed as effective cancer vaccines. MAbs 1:71-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pengelley, S. C., et al. 2006. A suite of parallel vectors for baculovirus expression. Protein Expr. Purif. 48:173-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pleass, R. J. 2009. Fc-receptors and immunity to malaria: from models to vaccines. Parasite Immunol. 31:529-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reagan-Shaw, S., M. Nihal, and N. Ahmad. 2008. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. 22:659-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reichert, J. M. 2011. Antibody-based therapeutics to watch in 2011. MAbs 3:76-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt, S. R. 2009. Fusion-proteins as biopharmaceuticals—applications and challenges. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 12:284-295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens, J., et al. 2006. Structure and receptor specificity of the hemagglutinin from an H5N1 influenza virus. Science 312:404-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Temperton, N. J., et al. 2007. A sensitive retroviral pseudotype assay for influenza H5N1-neutralizing antibodies. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses 1:105-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tosh, P. K., R. M. Jacobson, and G. A. Poland. 2010. Influenza vaccines: from surveillance through production to protection. Mayo Clin. Proc. 85:257-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Treanor, J. J., et al. 2006. Dose-related safety and immunogenicity of a trivalent baculovirus-expressed influenza-virus hemagglutinin vaccine in elderly adults. J. Infect. Dis. 193:1223-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tripp, R. A., and S. M. Tompkins. 2008. Recombinant vaccines for influenza virus. Curr. Opin. Invest. Drugs 9:836-845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, T. T., et al. 2010. Vaccination with a synthetic peptide from the influenza virus hemagglutinin provides protection against distinct viral subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:18979-18984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang, T. T., et al. 26 February 2010, posting date. Broadly protective monoclonal antibodies against H3 influenza viruses following sequential immunization with different hemagglutinins. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, W., et al. 2010. The hemagglutin protein 158N glycosylation and receptor binding specificity synergistically affect antigenicity and immunogenicity of a live attenuated H5N1 A/Vietnam/1203/2004 vaccine virus in ferrets. J. Virol. 84:6570-6577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weldon, W. C., et al. 2010. Enhanced immunogenicity of stabilized trimeric soluble influenza hemagglutinin. PLoS One 5:e12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamada, S., et al. 2006. Haemagglutinin mutations responsible for the binding of H5N1 influenza A viruses to human-type receptors. Nature 444:378-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang, Z. Y., et al. 2007. Immunization by avian H5 influenza hemagglutinin mutants with altered receptor binding specificity. Science 317:825-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zelenetz, A. D., and R. Levy. 1990. Directional cloning of cDNA using a selectable SfiI cassette. Gene 89:123-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang, M. Y., Y. Wang, M. K. Mankowski, R. G. Ptak, and D. S. Dimitrov. 2009. Cross-reactive HIV-1-neutralizing activity of serum IgG from a rabbit immunized with gp41 fused to IgG1 Fc: possible role of the prolonged half-life of the immunogen. Vaccine 27:857-863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao, Y., D. A. Chapman, and I. M. Jones. 2003. Improving baculovirus recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:E6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]