Abstract

Infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus (ISKNV), the type species of the genus Megalocytivirus in the family Iridoviridae, causes severe damage to mandarin fish cultures in China. Little is known about the proteins of ISKNV virions. In this study, a total of 38 ISKNV virion-associated proteins were identified by four different workflows with systematic and comprehensive proteomic approaches. Among the 38 identified proteins, 21 proteins were identified by the gel-based workflows (one-dimensional [1-D] and two-dimensional [2-D] gel electrophoresis). Fifteen proteins were identified by 1-D gel electrophoresis, and 16 proteins were identified by 2-D gel electrophoresis, with 10 proteins identified by both methods. Another 17 proteins were identified only by liquid chromatography (LC)-based workflows (LC-matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization [MALDI] and linear trap quadrupole [LTQ]-Orbitrap). Among these 17 LC-identified proteins, 5 proteins were identified uniquely by the LC-MALDI workflow, whereas another 6 proteins were identified only by the LTQ-Orbitrap workflow. These results underscore the importance of incorporation of multiple approaches in identification of viral proteins. Based on viral genomic sequence, genes encoding these 38 viral proteins were cloned and expressed in vitro. Antibodies were produced against these 38 proteins to confirm the ISKNV structural proteins by Western blotting. Of the newly identified proteins, ORF 056L and ORF 118L were identified and confirmed as two novel viral envelope proteins by Western blotting and immunoelectron microscopy (IEM). The ISKNV proteome reported here is currently the only characterized megalocytivirus proteome. The systematic and comprehensive identification of ISKNV structural proteins and their localizations in this study will facilitate future studies of the ISKNV assembly process and infection mechanism.

Over the past 20 years, emerging infectious iridoviruses have been considered one of the most important causative agents of viral diseases in fish (35). The family Iridoviridae is subdivided into five genera, Iridovirus, Chloriridovirus, Ranavirus, Lymphocystisvirus, and Megalocytivirus, as proposed by the eighth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (3). In recent years, megalocytiviruses have received increasing attention due to the ecological and economic impact that these viruses have on wild and cultured fish (1, 5, 21). Infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus (ISKNV), the type species of the genus Megalocytivirus, is devastating to the mandarin fish farm industry in China. The virus can cause 100% cumulative mortality in 4 to 10 days in farmed fish (10). A recent epidemiological investigation indicated that more than 50 species of cultured and wild marine fish are the confirmed hosts of ISKNV-like viruses in the South China Sea (31). Both clinical and asymptomatic infections with ISKNV-like megalocytiviruses were also reported in 10 freshwater ornamental species of fish in Korea (14). Furthermore, megalocytiviruses have become one of the most important agents of severe disease in fish farming facilities throughout Southeast Asia (4). Therefore, prevention and control of megalocytiviral infection are a priority for the fishing industry.

Since 2001, complete genome sequencing has been performed on five megalocytiviruses (1, 6, 10, 17, 20). A comparative genomic analysis has also been performed on the genome information of ISKNV (10), rock bream iridovirus (RBIV) (6), and orange-spotted grouper iridovirus (OSGIV) (17). The core set of megalocytivirus genes were reannotated and redefined recently (9). Current data show that megalocytiviruses have genome sizes between 111,316 and 112,168 nucleotides and consist of 118 to 125 open reading frames (ORFs). A functional genomic analysis would facilitate the progress of identifying viral gene function. However, until today, little work has been carried out on identifying the protein constituents of the megalocytiviral virion. A key obstacle in the study of megalocytiviruses is the lack of a suitable cell line for culturing viruses in vitro (2, 13). Recently, a mandarin fish fry cell line (MFF-1) showing high sensitivity to infection by ISKNV was successfully developed and used as an efficient cellular substrate for the growth of mandarin fish ISKNV and other megalocytiviruses (7, 8).

With the information on the ISKNV genome and the development of a suitable cell line, research studies are now focused on the functional study of the viral proteins. An essential element of such studies is the identification and characterization of viral structural proteins, because these structural proteins play crucial roles in both cell targeting and host defense evasion (29). Among structural proteins, envelope proteins are important due to their involvement in interactions between virus and host such as attachment to host receptors and fusion with host cell membranes during viral infection (39). Thus, intensive efforts have been undertaken to characterize and classify the structural proteins of ISKNV.

Mass spectrometry (MS) has been proven to be the most effective method for the discovery of functional proteins (25). Although peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) is a simple, fast, and accurate method for protein identification, several disadvantages exist when it is used to identify low-abundance proteins, proteins with extreme pI values, and proteins from a mixture (26). These limitations can be modified by using tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) (33). The development of a fast and highly sensitive linear trap quadrupole (LTQ)-Orbitrap mass spectrometer has also allowed for the identification of more proteins with greater confidence (16). In this study, a total of 38 proteins were identified as ISKNV virion-associated proteins by four proteomic workflows, including gel-based (one-dimensional [1-D] and two-dimensional [2-D] gel electrophoresis) and liquid chromatography (LC)-based (LC-matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization [MALDI] and LTQ-Orbitrap) workflows. Furthermore, 32 of the identified proteins were characterized as viral structural proteins by using specific antibodies. The characterized proteins include 3 envelope proteins (EP) and 29 other viral structural proteins. An initial functional protein map of ISKNV was established. This work represents the first comprehensive proteomic study of a megalocytivirus and aims to promote research on ISKNV and other megalocytiviruses. A better understanding of structural proteins and their localization in the virions will contribute to future studies of megalocytivirus assembly and infection pathways, as well as the discovery of vaccine candidates for megalocytivirus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ISKNV infection and purification.

ISKNV strain NH060831 and MFF-1 cell lines were characterized and kept in our laboratory (7). MFF-1 cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B (Invitrogen). When MFF-1 cultures were confluent, ISKNVs with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 were added to the flasks. At 4 to 5 days postinfection, infected MFF-1 cells were collected and then stored at −80°C. To purify ISKNV, the cells were first thawed and the cell suspension was treated by differential centrifugation, ultracentrifugation, and double sucrose density gradient centrifugation as previously described by Dong et al. (8). Viral purity was examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Viral protein concentrations were measured by the Bradford assay, and viral proteins were stored at −80°C.

2-D gel electrophoresis.

The first dimension of the 2-D procedure was performed in an IPGphor isoelectric focusing (IEF) system (GE Healthcare). One-hundred-microgram protein samples from the purified virions were applied onto each immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strip (pH 4 to 7 or nonlinear pH 3 to 10; 13 cm) (GE Healthcare). The IEF was performed at 20°C with a continuous increase of voltage (8,000 V to 16,000 V). The focused IPG strip was then equilibrated for 15 min in an equilibration buffer containing 20% (wt/vol) glycerol, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.002% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue. The strip was then further equilibrated for 15 min in a similar buffer replacing 100 mM DTT with 250 mM iodoacetamide. After equilibration, strips were loaded on the top of a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and sealed with hot agarose (1% [wt/vol]). After SDS-PAGE, protein spots were visualized with Coomassie brilliant blue staining (Sigma) and gels were scanned with ImageScanner (Amersham Biosciences, Sweden).

In-gel digestion and protein identification.

Protein spots of interest were manually excised from the gel and washed twice with 50% (vol/vol) acetonitrile (ACN) in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate for 15 min to remove the dye. After washing, gel plugs were shrunk by adding 100% (vol/vol) acetonitrile and vacuum dried. The dried gel pieces were rehydrated in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate containing 0.1 μg/μl sequencing-grade modified trypsin (Promega) and incubated at 37°C overnight. The in-gel tryptically digested peptides were then analyzed using a MALDI-time of flight (TOF)/TOF analyzer (Applied Biosystems 4700), which was calibrated using a mixture of 2 pmol angiotensin and 1.3 pmol Glu1-fibrinopeptide B peptide (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). Parameters and thresholds used for peak picking are as follows: mass range of 700 to 3,000 Da for parent mass peaks, minimal signal-to-noise (S/N) thresholds of >20 for PMF and >5 for MS/MS, and a resolution of >10,000. The resulting spectra were analyzed through the search engine MASCOT (version 2.0; Matrix Science). GPS Explorer software version 3.0 (Applied Biosystems) was used to create and search files with the MASCOT search engine for protein identification. The searching parameters were the NCBI nr database of ISKNV ORFs (no. AF371960), trypsin digest with one missing cleavage, MS tolerance of 100 ppm, and MS/MS tolerance of 0.6 Da; carbamidomethylation of cysteine was considered a fixed modification, while oxidation of methionine was considered a variable modification. The protein with the highest score (top rank) exceeding the 95% confidence level was generally considered the candidate for the target protein.

LC-MALDI MS/MS analysis.

Approximately 5 volumes of 0.1% SDS and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) were added to the purified ISKNV virions, incubated at 100°C, and vortexed until the viscous lump disappeared. After centrifugation, the supernatant was saved and the protein concentration was determined using the RC DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Extracted proteins (200 μg) were further diluted to 160 μl with 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, and 4 μl of 50 mM triscarboxyethylphosphine. The mixture was incubated at 100°C for 10 min. After cooling and incubation at 37°C for 2 h in the dark, 40 μl of 50 mM iodoacetamide was added to the sample. Milli-Q water (200 μl) containing 0.1 μg/μl sequencing-grade porcine trypsin was also added, and samples were incubated at 37°C overnight. Peptides obtained after digestion were subjected to LC-MALDI MS/MS analysis in the Research Center for Proteome Analysis (Shanghai, China) as described previously (26). Acquired MS/MS spectra were automatically searched in the GenBank virus protein database using the TurboSEQUEST program in the BioWorks 3.0 software package (version 3.1; Thermo). An accepted SEQUEST result must have a delCn score of at least 0.1 (regardless of charge state) and a cutoff of Rsp 4. The cross-correlation scores (Xcorr) of matches were greater than 1.9, 2.2, and 3.75 for charged states 1, 2, and 3 peptide ions, respectively.

Linear ion trap Orbitrap (LTQ-Orbitrap) analysis.

Trypsinized protein and peptide samples were separated on a C18 reversed-phase column (inner diameter of 100 μm; 10 cm long; 5-μm resins from Michrom Bioresources Inc., Auburn, CA) using a linear gradient from 5% B to 40% B in 60 min at a flow rate of 250 nl/min, where mobile phase A was composed of 0.1% (vol/vol) HCOOH and mobile phase B was 90% acetonitrile (ACN), 0.1% HCOOH. Collected samples were subjected to a linear ion trap in tandem with an Orbitrap (LTQ-Orbitrap) mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) at a spray voltage of 1.85 kV in the positive-ion mode. Peptide ions were analyzed as follows: full MS scan (350 to 1,800 m/z), zoom scan (scan of the 3 major ions), and MS/MS on these 3 ions with classical peptide fragmentation parameters (Qz of 0.25, activation time of 30 ms, and collision energy of 35%). The time during which the same ion cannot be reanalyzed was set to 30 s. Acquired data were automatically searched in the GenBank virus protein database using the SEQUEST program. The cross-correlation scores (Xcorr) of matches were greater than 2.0, 2.5, and 3.5 for charged states 1, 2, and 3 peptide ions, respectively.

Cloning of genes and purification of recombinant viral proteins.

Primers (data not shown) for viral genes identified by four proteomic workflows were designed according to ISKNV genomic sequences (AF371960) from NCBI. Standard PCR and molecular biology protocols were utilized to amplify the viral genes using ISKNV genomic DNA as a template. The PCR fragments were directionally cloned into plasmid pET-32a, digested with the corresponding enzyme, and then expressed in Escherichia coli BL21. Recombinant plasmids were detected using restriction enzyme analysis and sequencing. Overnight cultures of E. coli BL21 (Novagen, Germany) harboring recombinant plasmid were diluted to 1:100 (vol/vol) in fresh Luria broth with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and incubated at 37°C until the optical density was 0.6 at 600 nm. A final concentration of 1 mM/liter isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added in bacteria and incubated for 3 h at 37°C. Bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in buffer D (8 M urea, 0.1 M NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0). Cell suspensions were disrupted by sonication in an ice bath (300 W, three times for 10 min each) and centrifugation (7,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C). Supernatants containing recombinant proteins were subsequently purified by affinity chromatography on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) Superflow resin (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Unbound protein was removed by washing with buffer E (8 M urea, 0.1 M NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.3). Finally, purified recombinant proteins were eluted with buffer F (8 M urea, 0.1 M NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 5.9) and buffer G (8 M urea, 0.1 M NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 4.5). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay, and purified proteins were stored at −80°C.

Antibody preparation.

The purified virions and recombinant viral proteins were emulsified with equal volumes of Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA) for the first injection and Freund's incomplete adjuvant (FIA) for the two following injections. Rabbits received the three subcutaneous injections at 2-week intervals. Blood samples were taken on the 10th day after the last injection for serum collection. Thirty-two harvested antibodies against viral proteins of ISKNV were used for confirmation of structural proteins.

Fractionation of virion proteins by detergent treatment.

The fractionation of virion proteins was prepared based on a procedure described previously with modifications (37). In brief, the purified virus suspension was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The viral pellets were resuspended in salt-containing buffer TMN (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5). Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 1%, and the viral suspension was incubated at room temperature for 3 min. Subsequently, the samples were separated by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C into two fractions, supernatant and pellet. The pellet was rinsed with distilled water to eliminate any residual supernatant solution and then resuspended in TMN buffer. Finally, all samples were mixed with equal volumes of 2× Laemmli sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 25% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 5% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol) and resolved by SDS-PAGE (18).

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

To resolve viral proteins, a discontinuous buffer system of Laemmli buffer with 12% resolving gels and 4% stacking gels was used. All samples were heated for 10 min in boiling water and electrophoresed with a constant voltage of 120 V until the dye front reached the bottom of the gel. Protein bands were visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. Western blotting was performed according to the procedure described previously (38). Proteins from the gels were transferred to nitrocellulose (NC) membranes for 1 h at 70 V in transfer buffer (48 mM Tris, 39 mM glycine, 20% [vol/vol] methanol, pH 8.3) at 4°C. The NC membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% (wt/vol) skim milk in TNT buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% [vol/vol] Tween 20, pH 7.0) at 24°C. After being rinsed three times for 10 min with TNT buffer, NC membranes were incubated with these rabbit antisera at a proper dilution (1:2,000 to ∼4,000) in a TNT buffer containing 5% (wt/vol) skim milk for 1 h at 24°C with gentle shaking. The membranes were rinsed three times for 10 min with TNT buffer and incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG-conjugated alkaline phosphatase (Sigma) at 1:10,000 in a TNT buffer containing 5% (wt/vol) skim milk for 1 h at 24°C. Membranes were then washed with TNT buffer and developed with nitroblue tetrazolium-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (NBT-BCIP) (Sigma) substrate solution until optimum color developed.

Localization of ORFs 007L, 056L, and 118L by immunoelectron microscopy (IEM).

Purified viral virions were absorbed into Formvar-coated, carbon-stabilized 200-mesh nickel grids for 15 min at room temperature. The grids were blocked with 2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min at room temperature. Grids were then rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with diluted primary antibodies for ORF 007L, 056L, or 118L. The primary antibodies were diluted 1:100 in PBS buffer. After being washed with PBS, the grids were incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with 10-nm colloidal gold (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature, washed, and negatively stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid (PTA). Specimens were examined with a transmission electron microscope (JEM-100CX II; Japan).

RESULTS

Identification of ISKNV major structural proteins by 1-D MS.

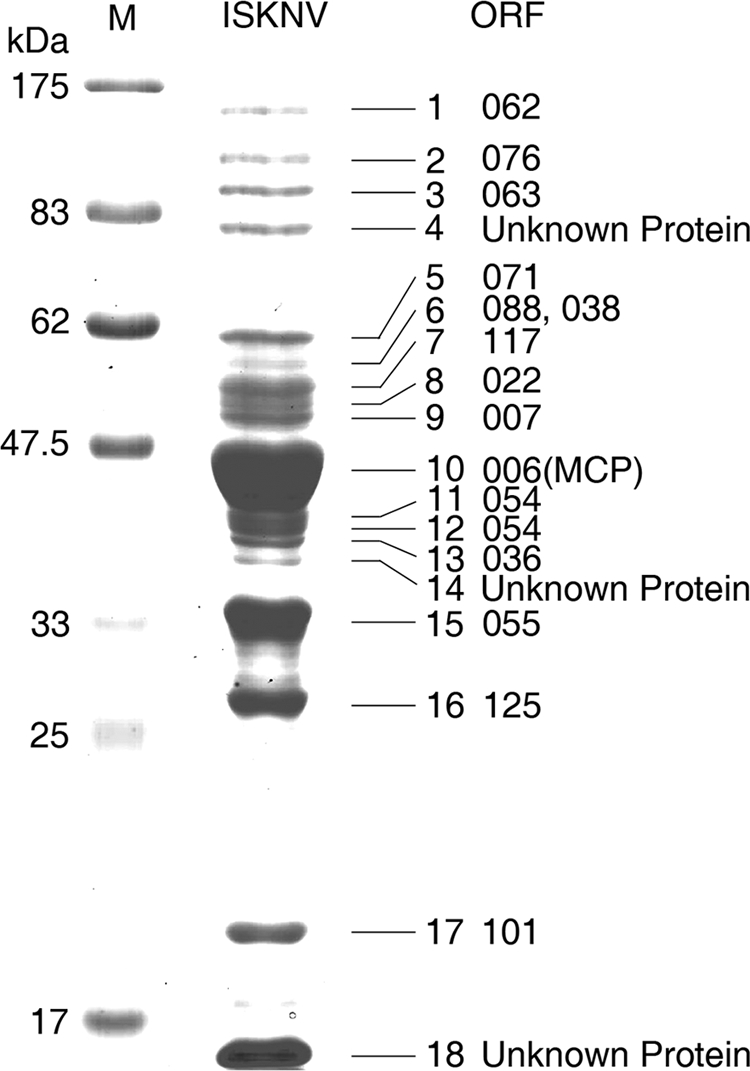

ISKNV was proliferated in a mandarin fish fry cell line (MFF-1), which showed high sensitivity to infection by this virus. Virus purification was performed according to a procedure described previously (8). Purified viral proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE. Approximately 18 bands ranging from 10 to 180 kDa were visible by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (Fig. 1). Subsequently, all these 18 bands were excised from the gel for further MS analysis. Following trypsin digestion of the reduced and alkylated protein bands, the resulting peptides were analyzed by MALDI-TOF-TOF MS/MS. The MS data for each digested protein were subjected to an ISKNV ORF database search using the MASCOT search engine to identify the proteins and corresponding genes. Fifteen proteins were matched to ISKNV with high confidence (data not shown). These 15 viral proteins include 006L, 007L, 022L, 036R, 038L, 054L, 055L, 062L, 063L, 071L, 076L, 088R, 101L, 117L, and 125L. As shown in Fig. 1, the major viral proteins of ISKNV consist of the major capsid protein (ORF 006L), a serine-threonine protein kinase (ORF 055L), an ankyrin repeat protein (ORF 125L), and an uncharacterized protein (ORF 101L). These four are the most abundant proteins in ISKNV.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE profiles of purified ISKNV virions. Viral proteins were visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 staining. A gel having a gradient of 4 to 12% was used for electrophoresis. Numbers indicate the excised bands. M, broad-range prestained protein marker (NEB).

Identification of structural proteins by 2-D MS.

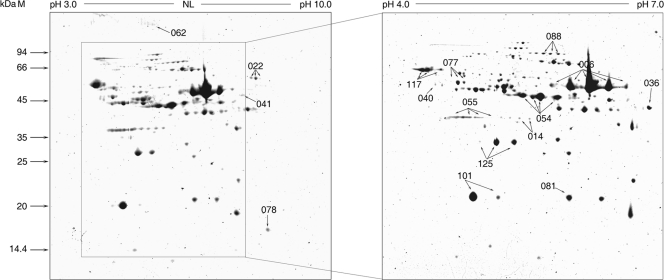

The purified virions were subjected to 2-D analysis to achieve a more comprehensive and precise characterization of the ISKNV virons. This was accomplished using different pH gradient strips of 13 cm in length and covering a pH range of 4 to 7 and pH 3 to 10 (Fig. 2). After separation of proteins from purified virions by 2-D gel electrophoresis, the spots detected by Coomassie brilliant blue staining in the 2-D profile were assumed to be viral structural proteins. All visible spots were excised and subjected to MS analysis. After the ISKNV ORF database was searched, 16 2-D spots were identified by MS (data not shown). Of the 16 proteins identified by the combination of 2-D analysis and MS, 10 proteins (ORFs 006L, 022L, 036R, 054L, 055L, 062L, 088R, 101L, 117L, and 125L) were revealed by a combination of 1-D SDS-PAGE and MS/MS. The remaining six proteins (ORFs 014R, 040L, 041L, 077R, 078R, and 081R) were identified by 2-D MS.

FIG. 2.

The 2-D map of the purified ISKNV virions. Protein samples were separated in the first dimension by IEF, while the second-dimension procedure was performed using 12% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were detected by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. The gel was run in a 13-cm pH 3 to 10 (left) nonlinear IPG and in a pH 4 to 7 (right) linear IPG, respectively. Molecular masses are shown on the far left. Successfully identified proteins are labeled.

Identification of virion-associated proteins by LC-MALDI.

The whole virus was digested by trypsin. The tryptic peptide mixture of the ISKNV proteins was separated using a reverse-phase nano-LC column. Three separate LC-MALDI runs were performed with different ACN gradients to obtain thorough separation of peptides. A total of 32 viral proteins with peptide sequences that matched the ISKNV ORFs were detected (data not shown). The identified proteins contained at least one top-ranked peptide having a MASCOT expectation value of <0.05. The LC workflows identified a total of 27 potential viral proteins. Among these 27 identified proteins, there were 15 proteins identified only by 1-D MALDI, 16 proteins identified only by 2-D MALDI, and 21 proteins identified through both gel approaches and MS. Eleven additional proteins of ISKNV (corresponding to ORFs 012R, 037L, 039R, 043L, 044L, 056L, 068L, 093L, 095L, 111L, and 119L) that were not detected using gel-based approaches were also identified.

Identification of viral proteins by LTQ-Orbitrap.

Analysis of the tryptic peptide mixture from ISKNV was also performed with LTQ-Orbitrap. To maximize the sensitivity and reliability of protein identification, all MS/MS spectra from the three runs were combined for the database. As a result, 33 proteins were identified with high confidence (data not shown). Among them, 27 proteins which were detected by LC-MALDI analysis were also detected by LTQ-Orbitrap. Six additional proteins, corresponding to ORFs 033L, 045L, 100L, 109L, 115R, and 118L, were identified only by LTQ-Orbitrap. These six novel viral proteins were further verified by Western blotting. The validation confirms the result of the proteomic LTQ approach. Altogether, the four proteomic workflows described above led to the identification of 38 potential viral proteins in ISKNV. The 38 ISKNV virion-associated proteins identified by four different proteomic workflows are summarized in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Summary of ISKNV structural proteins identified by four different proteomic workflows. (A) Proteins identified by gel-based MS and LC-MALDI MS. (B) Proteins identified by LC-based MS. The overlapped regions represent proteins identified by both workflows.

Identification and characterization of ISKNV structural proteins.

Western blotting was performed to confirm the viral proteins identified by the four proteomic workflows. All these 38 identified virion-associated protein genes were cloned from the ISKNV genome and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3). Furthermore, 38 antibodies of these recombinant viral proteins were prepared. Western blot analysis showed that 32 of the 38 antibodies recognized protein bands of the expected molecular masses (data not shown). The remaining six antibodies (targeted to ORFs 012R, 038L, 043L, 068L, 111L, and 119R) did not bind to viral protein bands. All the antisera used in Western blot analysis are summarized in Table 1. In this study, 32 apparent specific bands on the Western blotting map were found (data not shown). The results of Western blotting also indicated that MS results were reliable.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the identification and classification of structural proteins in ISKNV

| No. | Protein (ORF) | Accession no. | TMa | PSORTb | Location in the virionc | Classification methodd | Identification methode: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-D | 2-D | LC-MALDI | LTQ | |||||||

| 1 | 006L | Q8V5D9 | TM | C | MCP | WB | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | 007L | Q8QUV3 | TM | Mb | EP | IEM, WB | + | − | + | + |

| 3 | 012R | Q8QUU8 | N | U | − | − | + | − | ||

| 4 | 014R | Q8QUU6 | TM | C | U | WB | − | + | + | + |

| 5 | 022L | Q8QUT8 | TM | C | U | WB | + | + | + | + |

| 6 | 033L | Q8QUS7 | TM | N | U | WB | − | − | − | + |

| 7 | 036R | Q8QUS4 | TM | Mt | U | WB | + | + | + | + |

| 8 | 037L | Q8QUS3 | C | U | WB | − | − | + | + | |

| 9 | 038L | Q8QUS2 | C | U | + | − | + | + | ||

| 10 | 039R | Q8QUS1 | TM | C | U | WB | − | − | + | + |

| 11 | 040L | Q8QUS0 | TM | C | U | WB | − | + | + | + |

| 12 | 041L | Q8QUR9 | TM | C | U | WB | − | + | + | + |

| 13 | 043L | Q8QUR7 | TM | C | U | − | − | + | − | |

| 14 | 044L | Q8QUR6 | C | U | WB | − | − | + | + | |

| 15 | 045L | Q8QUR5 | C | U | WB | − | − | − | + | |

| 16 | 054L | Q8QUQ6 | Mt | U | WB | + | + | + | + | |

| 17 | 055L | Q8QUQ5 | N | U | WB | + | + | + | + | |

| 18 | 056L | Q8QUQ4 | TM | C | EP | IEM, WB | − | − | + | − |

| 19 | 062L | Q8QUP8 | TM | N | U | WB | + | + | + | + |

| 20 | 063L | Q8QUP7 | TM | C | U | WB | + | − | + | + |

| 21 | 068L | Q8QUP2 | TM | C | U | − | − | + | + | |

| 22 | 071L | Q8QUN9 | TM | C | U | WB | + | − | + | + |

| 23 | 076L | Q8QUN4 | C | U | WB | + | − | + | + | |

| 24 | 077R | Q8QUN3 | C | U | WB | − | + | + | + | |

| 25 | 078R | Q8QUN2 | C | U | WB | − | + | + | − | |

| 26 | 081R | Q8QUM9 | C | U | WB | − | + | + | + | |

| 27 | 088R | Q8QUM2 | Mt | U | WB | + | + | + | + | |

| 28 | 093L | Q8QUL7 | Mt | U | WB | − | − | + | − | |

| 29 | 095L | Q8QUL5 | TM | C | U | WB | − | − | + | + |

| 30 | 100L | Q8QUL0 | C | U | WB | − | − | − | + | |

| 31 | 101L | Q8QUK9 | C | U | WB | + | + | + | + | |

| 32 | 109L | Q8QUK1 | TM | C | U | WB | − | − | − | + |

| 33 | 111L | Q8QUJ9 | TM | C | U | − | − | + | + | |

| 34 | 115R | Q8QUJ5 | TM | C | U | WB | − | − | − | + |

| 35 | 117L | Q8QUJ3 | TM | C | U | WB | + | + | + | + |

| 36 | 118L | Q8QUJ2 | C | EP | IEM, WB | − | − | − | + | |

| 37 | 119R | Q8QUJ1 | TM | C | U | − | − | + | + | |

| 38 | 125L | Q8QUI6 | C | U | WB | + | + | + | + | |

TM, transmembrane domain.

N, nuclear; C, cytoplasmic; Mb, membrane; Mt, mitochondrial.

EP, envelope protein; MCP, major capsid protein; U, unknown.

Classification method: method used for protein classification. WB, Western blotting; IEM, immunoelectron microscopy.

Identification method: 1-D, detected by one-dimensional gel electrophoresis; 2-D, detected by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis; LC-MALDI, identified by LC-MALDI; LTQ, identified by LTQ-Orbitrap.

Classification of ISKNV structural proteins.

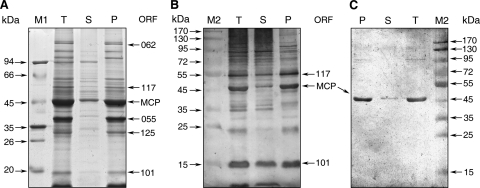

Besides identifying viral proteins, we further characterized these identified proteins by classifying them into core and membrane proteins. In order to acquire a clearer classification of these proteins, 32 specific antibodies were used to recognize the fractionated proteins. To locate the viral proteins in the virion structure, core and soluble protein components were prepared from purified intact ISKNV virions. Triton X-100 was used to separate purified virions into insoluble core component (pellet) and soluble protein component (supernatant) fractions. The supernatant and pellet fractions were loaded on gels and transferred to NC membranes. After being blocked with skim milk, the NC membranes were cut into strips and separately incubated with 32 different antibodies. SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the purified viral proteins are divided into two fractions (Fig. 4 A). The pellet fraction contained most of the viral proteins of ISKNV, while the supernatant fraction consisted of only a few proteins. Among the viral proteins, ORF 062, encoding protein VP62, the largest-molecular-mass protein in ISKNV, was found to exist only in the pellet fraction. ORF 117 and ORF 101, encoding proteins VP117 and VP101, respectively, were observed in both pellet and supernatant fractions. Furthermore, ORF 055 and ORF 125, encoding proteins VP55 and VP125, respectively, were found in the pellet. A few proteins were also found in the supernatant with uncertain origins. For example, band 4 in Fig. 1 is a high-abundance protein from the purified ISKNV virions and is found in the supernatant of detergent-treated ISKNV solution (Fig. 4A). Although a confident PMF was acquired, no acceptable search result was found in current MS analysis (data not shown). Therefore, it may be an unknown host (fish) protein. Because the genome of mandarin fish is still not available, the identity of these potential host proteins is difficult to determine. As for the major capsid protein (MCP), which is the most abundant protein in iridovirus, MCP was found in both pellet and supernatant with the majority being found in pellet (Fig. 4A). Similar results were also observed with Western blot analysis. Figure 4B reveals that VP117, MCP, and VP101 are found in both fractions by Western blot analysis when rabbit anti-ISKNV virion serum was used as the primary antibody. However, with rabbit anti-recombinant MCP serum used as the primary antibody, Western blotting showed that MCP exists mainly in the pellet fraction and little of it exists in the supernatant fraction (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Profiles of detergent-treated ISKNV virions. (A) SDS-PAGE (12%) gel stained with CBBR-250. (B) Western blot profiles with rabbit anti-purified ISKNV virion serum as the first antibody. (C) Western blotting profiles using rabbit anti-recombinant MCP serum as the first antibody. M1, medium-range protein molecular mass marker; M2, prestained broad-range protein molecular mass marker; T, total proteins of purified ISKNV virions; S, supernatant fraction of detergent-treated ISKNV virons; P, pellet fraction of detergent-treated ISKNV virions.

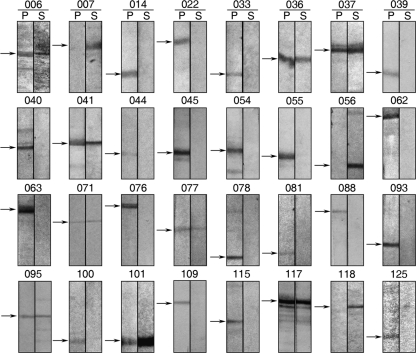

As shown in Fig. 5, among the 32 viral proteins analyzed by Western blotting, the proteins encoded by ORFs 056L and 118L were always found solely in the soluble components. This result suggests that these are two novel viral envelope proteins. As a representative control, the known putative envelope protein encoded by ORF 007 was also found exclusively in the supernatant fraction (Fig. 5). Proteins encoded by ORFs 014R, 022L, 033L, 039R, 040L, 044L, 045L, 054L, 055L, 062L, 063L, 076L, 078R, 081R, 088R, 093L, 100L, 109L, 115R, and 125L were exclusively present in the pellet of insoluble core components after detergent extraction. Proteins encoded by ORFs 036R, 037L, 041L, 071L, 077R, 095L, 101L, and 117L were partitioned into both the supernatant and pellet fractions.

FIG. 5.

Western blotting of 32 structural proteins of ISKNV. Intact ISKNV virions were subjected to 1% Triton X-100 treatment. After fractionation, the pellet and supernatant fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and further analyzed by Western blot analysis using 32 specific recombinant viral protein antibodies.

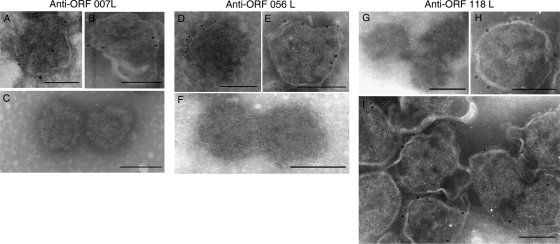

Localization of ORFs 007L, 056L, and 118L by IEM.

Western blot analysis showed that proteins encoded by ORFs 007L, 056L, and 118L are putative envelope proteins of ISKNV. Thus, immunoelectron microscopy (IEM) was applied to further confirm the location of the viral proteins encoded by these ORFs in ISKNV virions. IEM analysis agrees with the classification results. After labeling virions with primary antibody (against proteins encoded by ORF 007L, 056L, or 118L, respectively) and secondary antibodies conjugated with gold particles, gold particles were observed on the surface of ISKNV virions (Fig. 6). In the control experiments, no gold particles were observed for ISKNV virions with preimmune serum used as the primary antibody (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Localization of ORFs 007L, 056L, and 118L in the ISKNV virions by immunoelectron microscopy. Purified virus particles (A, B, D, E, H, and I) and viral nucleocapsids (C, F, and G) were detected using immunogold-labeled anti-ORF 007L, anti-ORF 056L, and anti-ORF 118L antibodies. The anti-ORF 007L, anti-ORF 056L, or anti-ORF 118L antibody bound only to the envelope and not to the viral nucleocapsid. Bar, 100 nm.

DISCUSSION

Over the past decade, iridovirus research has generated increasing interest because of the high infectivity and pathogenicity of these viruses in aquaculture industries. However, few of the functional genes that encode the structural proteins involved in virus infection, replication, and virus-host interactions have been characterized (32). In this study, four proteomic workflows were applied to identify and characterize virion-associated proteins of ISKNV. A total of 38 viral proteins were identified, and 32 of the structural proteins were further confirmed by Western blot analysis with 32 individual antibodies.

Our study demonstrated and underscored the importance of applying multiple workflows for identification of viral proteins because of the limitations of individual workflows. Recently, MALDI-TOF and LC-MS/MS have been widely used in the study of virions (12, 19, 28, 39). The protein components associated with virions from cyprinid herpesvirus 3 (CyHV-3) were identified solely using an LC-based proteomic workflow (23). Two workflows including traditional one-dimensional gel electrophoresis (1-D MALDI workflow) and shotgun proteomics (LC-MALDI workflow) were used in combination to identify 44 viral proteins of the Singapore grouper iridovirus (SGIV) of the genus Ranavirus in the family Iridoviridae (26). In contrast with the use of one or two proteomic workflows, a more systematic, comprehensive, and precise determination of the ISKNV proteome was achieved in this study by applying four proteomic workflows. Each proteomic workflow validates and supplements the other workflows. In gel-based proteomics, proteins were visualized by staining with dye solution or radioactive labeling. In these techniques, silver stain and radioactive label are much more sensitive than Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (CBBR-250) stain. We have attempted to obtain more viral protein information by silver staining 1-D gels. MS revealed that these additional identified proteins are mostly unknown proteins or host proteins (data not shown). The present work revealed only the CBBR-250 staining results. In this study, a total of 21 proteins, consisting of highly abundant proteins in ISKNV, were identified by gel-based approaches with CBBR-250 staining. Proteins encoded by ORF 006 (MCP), ORF 055, ORF 125, and ORF 101 are the four most abundant proteins in ISKNV. Among the viral proteins identified by LC-based proteomics, some may be present in the virions only in very low abundance. These low-abundance proteins cannot be identified in gel-based analyses because only visible and bright bands were excised from the gels for further analysis. Therefore, LC-based approaches have an advantage in identifying low-abundance proteins such as proteins encoded by ORFs 056L and 093L. Moreover, several highly basic proteins such as those encoded by ORFs 006L and 101L were also identified in the LC method.

Comprehensive proteomics has been performed to identify SGIV virion proteins from purified virions in piscine iridovirus (26, 27). In the 162 ORFs of SGIV, a total of 44 proteins were identified as virion-associated proteins. Thus, the ratio of the identified proteins for SGIV was 27.16% (44/162). In our study of ISKNV, the ratio of the identified proteins is 30.4% (38/125). The ratio of the immunoconfirmed structural proteins in ISKNV ORFs is 25.6% (32/125). SGIV and ISKNV have the same approximate ratios of virion-associated proteins in their total ORFs. However, only a few homologous proteins were found in both ISKNV and SGIV, possibly because they are two different iridoviral genera. Compared with the study in SGIV, our study further confirmed the identified proteins by Western blot assay. Among the 38 identified proteins, 32 were immunoconfirmed with Western blotting. Six proteins were not detected in Western blot assays. This result may be due to the relatively low abundance of these proteins in virions or due to the low affinity of the corresponding antibodies. We are currently investigating these issues.

Most recently, major viral proteins of a marine megalocytivirus (SKIV-ZJ07) have been determined based on one-dimensional (1-D) gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry (MS). A total of 19 novel megalocytiviral proteins, including 16 homologous proteins found in ISKNV, were identified in this virus (8). Thus, excluding the identified proteins in our previous study of spotted knifejaw iridovirus (SKIV), a total of 22 new viral proteins of megalocytivirus were identified in this study. The newly identified proteins encoded by ORF 012R, ORF 111L, and ORF 119R are three RING finger proteins. ORF 012R and ORF 111L possessed ubiquitin E3 activity in the presence of ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), ubiquitin, and zinc ion (36). Proteins encoded by ORF 055L, ORF 077R, ORF 118L, and ORF 125L are four ankyrin repeat proteins. A protein encoded by ORF 118L was found only in the supernatant fraction, and proteins encoded by ORF 055L and ORF 125L were found exclusively in the pellet fraction, whereas a protein encoded by ORF 077R was found in both supernatant and pellet fractions. The relationships among these four proteins are interesting topics for further studies.

Detergents are indispensable in the isolation of envelope proteins from enveloped virions and in the investigation of their intrinsic structural and functional properties (23, 37). The envelope of white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) has been reported to be susceptible to the nonionic detergent Triton X-100 (19, 30, 37, 41). The effects of Triton X-100 detergents on treatment of the outer surface proteins have also been analyzed in other two genera of iridoviruses, Ranavirus and Lymphocystisvirus (LDV) (11). In the study by Heppell and Berthiaume, LDV and frog virus 3 (FV3) appeared to have roughly similar ultrastructures, composed of two layers of surface proteins surrounding a lipidic membrane. The surface proteins could be released in some degree after treatment with detergents such as 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (11). As for megalocytivirus, little work has been done to determine its fine ultrastructure. However, studies on ultrastructural morphology and morphogenesis of Taiwan grouper iridovirus (TGIV), another member of the genus Megalocytivirus, suggest that megalocytivirus may have structural levels similar to those of two other genera of piscine iridoviruses (Ranavirus and Lymphocystisvirus) (2). Triton X-100 (1% [vol/vol]) is a suitable detergent for separating the envelopes from other viral components. Therefore, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 detergent was utilized in extracting envelope proteins from the ISKNV virions. Furthermore, MCP is known to have the most abundant protein localization between the outermost envelope layer and the inner membrane. Thus, MCP is the essential marker in assessing the extraction effect of detergent treatment. In this study, SDS-PAGE combined with Western blot analysis showed that MCPs were found mainly in the pellet fraction and only a small amount of them was found in the supernatant fraction upon treatment with 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 3 min (Fig. 4A to C). We conclude that treatment with 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 3 min was the reasonable approach for extraction of the envelope protein of ISKNV. The outermost envelope proteins should have been dissociated from the virions previously because the detergent has degraded the intermediate layer, such as MCP.

After detergent treatment and fractionation, SDS-PAGE analysis showed that none of the major structural proteins were indicated as the envelope protein, except for one unknown highly abundant protein (band 4 in Fig. 1). On the other hand, the major structural proteins mainly existed in the pellet fraction, a finding which was greatly different from those for the other two enveloped large aquatic DNA viruses, cyprinid herpesvirus 3 (CyHV-3) and white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) (23, 30, 37). In CyHV-3 and WSSV, the envelope proteins are composed of many highly abundant viral proteins. However, iridoviruses have a different virion structure with an innermost protein-DNA core, an internal lipid membrane, an icosahedral capsid, and, in some cases, viral envelope (4, 34). The current study also shows that envelopes in ISKNV are composed of a limited number of low-abundance viral proteins.

Enveloped viruses normally have the ability to incorporate both viral and host proteins into their membrane and the envelope. These proteins are present at low levels, making their detection difficult (22). These proteins are nonetheless important because they usually play vital roles in receptor binding or the process of entering into host cells by membrane fusion (24). Combining immunoblotting experiments and IEM assay, we confirmed that proteins encoded by ORFs 007L, 056L, and 118L are envelope proteins. The protein encoded by ORF 007L is homologous to the known envelope protein ORF 53R of Rana grylio virus (40). Recently, ORF 53R in FV3 (protein/gene identical to ORF 53R in Rana grylio virus) was demonstrated to be an essential viral molecule involved in virus replication in vitro (34). A protein encoded by ORF 112L in RBIV (a molecule homologous to a protein encoded by ORF 118L in ISKNV) displayed some degree of antibody-neutralizing activity in an in vitro experiment (15). Moreover, ORF 056L is confirmed as a low-abundance envelope protein with unknown function. Further work will be done to investigate the interaction between these envelope proteins and other viral structural proteins or some receptor proteins from a sensitive host.

Aside from 3 envelope proteins and the known MCP, the specific localizations of 28 proteins in the ISKNV virion are still unclear. These proteins include 20 proteins existing only in the pellet fraction of detergent-treated virions and 8 proteins existing in both the pellet and supernatant. Future study will focus on their specific localizations in virion structure and their potential functions in virus formation and infection.

In conclusion, we report the identification of 38 viral proteins in ISKNV virions based on four different proteomic approaches. The functional protein map of ISKNV has been primarily established, and this is the first comprehensive proteome study of a megalocytivirus that will help promote the progress of research on ISKNV and other megalocytiviruses. The identification of proteins incorporated into ISKNV particles and classification of the localization of viral proteins in virions are key milestones for further fundamental and applied research on this virus and for the development of vaccine candidates.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their critical comments on the manuscript; John F. Zhong at the Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, for his comments on manuscript modification; and Chang-Jun Guo at Sun Yat-sen University for his contribution of the antibodies to ORF 077 and ORF 125.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grants 30325035, U0631008, and 31001122; the National Basic Research Program of China under grant 2006CB101802; the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) under grants 2006AA09Z445 and 2006AA100309; and the first class supporting project 20090450193 of the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ao, J., and X. Chen. 2006. Identification and characterization of a novel gene encoding an RGD-containing protein in large yellow croaker iridovirus. Virology 355:213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chao, C. B., C. Y. Chen, Y. Y. Lai, C. S. Lin, and H. T. Huang. 2004. Histological, ultrastructural, and in situ hybridization study on enlarged cells in grouper Epinephelus hybrids infected by grouper iridovirus in Taiwan (TGIV). Dis. Aquat. Organ. 58:127-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinchar, V. G., et al. 2005. Family Iridoviridae, p. 145-161. In C. M. Fauquet, M. A. Mayo, J. Maniloff, U. Desselberger, and L. A. Ball (ed.), Virus taxonomy. Eighth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 4.Chinchar, V. G., A. Hyatt, T. Miyazaki, and T. Williams. 2009. Family Iridoviridae: poor viral relations no longer. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 328:123-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Do, J. W., et al. 2005. Phylogenetic analysis of the major capsid protein gene of iridovirus isolates from cultured flounders Paralichthys olivaceus in Korea. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 64:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Do, J. W., et al. 2004. Complete genomic DNA sequence of rock bream iridovirus. Virology 325:351-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong, C., et al. 2008. Development of a mandarin fish Siniperca chuatsi fry cell line suitable for the study of infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus (ISKNV). Virus Res. 135:273-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong, C., et al. 2010. A new marine megalocytivirus from spotted knifejaw, Oplegnathus punctatus, and its pathogenicity to freshwater mandarinfish, Siniperca chuatsi. Virus Res. 147:98-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eaton, H. E., et al. 2007. Comparative genomic analysis of the family Iridoviridae: re-annotating and defining the core set of iridovirus genes. Virol. J. 4:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He, J. G., et al. 2001. Complete genome analysis of the mandarin fish infectious spleen and kidney necrosis iridovirus. Virology 291:126-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heppell, J., and L. Berthiaume. 1992. Ultrastructure of lymphocystis disease virus (LDV) as compared to frog virus 3 (FV3) and chilo iridescent virus (CIV): effects of enzymatic digestions and detergent degradations. Arch. Virol. 125:215-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang, C., et al. 2002. Proteomic analysis of shrimp white spot syndrome viral proteins and characterization of a novel envelope protein VP466. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1:223-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imajoh, M., T. Ikawa, and S. Oshima. 2007. Characterization of a new fibroblast cell line from a tail fin of red sea bream, Pagrus major, and phylogenetic relationships of a recent RSIV isolate in Japan. Virus Res. 126:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeong, J. B., et al. 2008. Outbreaks and risks of infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus disease in freshwater ornamental fishes. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 78:209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, Y. I., Y. M. Ha, Y. K. Nam, K. H. Kim, and S. K. Kim. 2008. Production of polyclonal antibody against recombinant ORF 112 L of rock bream (Oplegnathus fasciatus) iridovirus (RBIV) and in vitro neutralization. J. Environ. Biol. 29:571-576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kocher, T., et al. 2009. High precision quantitative proteomics using iTRAQ on an LTQ Orbitrap: a new mass spectrometric method combining the benefits of all. J. Proteome Res. 8:4743-4752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurita, J., K. I. H. Nakajima, and T. Aoki. 2002. Complete genome sequencing of red sea bream iridovirus (RSIV). Fish. Sci. 68:1113-1115. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, Z., et al. 2007. Shotgun identification of the structural proteome of shrimp white spot syndrome virus and iTRAQ differentiation of envelope and nucleocapsid subproteomes. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6:1609-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lü, L., et al. 2005. Complete genome sequence analysis of an iridovirus isolated from the orange-spotted grouper, Epinephelus coioides. Virology 339:81-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lua, D. T., M. Yasuike, I. Hirono, and T. Aoki. 2005. Transcription program of red sea bream iridovirus as revealed by DNA microarrays. J. Virol. 79:15151-15164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maxwell, K. L., and L. Frappier. 2007. Viral proteomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71:398-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michel, B., et al. 2010. The genome of cyprinid herpesvirus 3 encodes 40 proteins incorporated in mature virions. J. Gen. Virol. 91:452-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Modis, Y., S. Ogata, D. Clements, and S. C. Harrison. 2004. Structure of the dengue virus envelope protein after membrane fusion. Nature 427:313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramaroson, M. F., J. Ruby, M. B. Goshe, and H. C. Liu. 2008. Changes in the Gallus gallus proteome induced by Marek's disease virus. J. Proteome Res. 7:4346-4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song, W., Q. Lin, S. B. Joshi, T. K. Lim, and C. L. Hew. 2006. Proteomic studies of the Singapore grouper iridovirus. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5:256-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song, W. J., et al. 2004. Functional genomics analysis of Singapore grouper iridovirus: complete sequence determination and proteomic analysis. J. Virol. 78:12576-12590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan, Y., D. K. Bideshi, J. J. Johnson, Y. Bigot, and B. A. Federici. 2009. Proteomic analysis of the Spodoptera frugiperda ascovirus 1a virion reveals 21 proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 90:359-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai, J. M., et al. 2004. Genomic and proteomic analysis of thirty-nine structural proteins of shrimp white spot syndrome virus. J. Virol. 78:11360-11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai, J. M., et al. 2006. Identification of the nucleocapsid, tegument, and envelope proteins of the shrimp white spot syndrome virus virion. J. Virol. 80:3021-3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, Y. Q., et al. 2007. Molecular epidemiology and phylogenetic analysis of a marine fish infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus-like (ISKNV-like) virus. Arch. Virol. 152:763-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, Z. L., et al. 2008. Infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus ORF48R functions as a new viral vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Virol. 82:4371-4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westermeier, R., and T. Naven. 2002. Proteomics in practice: a laboratory manual of proteome analysis, p. 143-145. Wiley-VCH Verlag-GmbH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 34.Whitley, D. S., et al. 2010. Frog virus 3 ORF 53R, a putative myristoylated membrane protein, is essential for virus replication in vitro. Virology 405:448-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams, T., V. Barbosa-Solomieu, and V. G. Chinchar. 2005. A decade of advances in iridovirus research. Adv. Virus Res. 65:173-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie, J., et al. 2007. RING finger proteins of infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus (ISKNV) function as ubiquitin ligase enzymes. Virus Res. 123:170-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie, X., L. Xu, and F. Yang. 2006. Proteomic analysis of the major envelope and nucleocapsid proteins of white spot syndrome virus. J. Virol. 80:10615-10623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiong, X. P., et al. 2010. Differentially expressed outer membrane proteins of Vibrio alginolyticus in response to six types of antibiotics. Mar. Biotechnol. (N.Y.) 12:686-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang, X., C. Huang, X. Tang, Y. Zhuang, and C. L. Hew. 2004. Identification of structural proteins from shrimp white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) by 2DE-MS. Proteins 55:229-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao, Z., et al. 2008. Identification and characterization of a novel envelope protein in Rana grylio virus. J. Gen. Virol. 89:1866-1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou, Q., L. Xu, H. Li, Y. P. Qi, and F. Yang. 2009. Four major envelope proteins of white spot syndrome virus bind to form a complex. J. Virol. 83:4709-4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]