Abstract

Purpose

A phase III trial (Cancer and Leukemia Group B CALGB-49907) was conducted to test whether older patients with early-stage breast cancer would have equivalent relapse-free and overall survival with capecitabine compared with standard chemotherapy. The quality of life (QoL) substudy tested whether capecitabine treatment would be associated with a better QoL than standard chemotherapy.

Patients and Methods

QoL was assessed in 350 patients randomly assigned to either standard chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil [CMF] or doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide [AC]; n = 182) or capecitabine (n = 168). Patients were interviewed by telephone before treatment (baseline), midtreatment, within 1 month post-treatment, and at 12, 18, and 24 months postbaseline by using questionnaires from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30), a breast systemic adverse effects scale (EORTC BR23), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

Results

Compared with patients who were treated with standard chemotherapy, patients who were treated with capecitabine had significantly better QoL, role function, and social function, fewer systemic adverse effects, less psychological distress, and less fatigue during and at the completion of treatment (P ≤ .005). Capecitabine treatment was associated with less nausea, vomiting, and constipation and with better appetite than standard treatment (P ≤ .004), but worse hand-foot syndrome and diarrhea (P < .005). These differences all resolved by 12 months.

Conclusion

Standard chemotherapy was superior to capecitabine in improving relapse-free and overall survival for older women with early-stage breast cancer. Although capecitabine was associated with better QoL during treatment, QoL was similar for both groups at 1 year. The brief period of poorer QoL with standard treatment is a modest price to pay for a chance at improved survival.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) conducted a randomized phase III trial (CALGB 49907) to test whether patients randomly assigned to capecitabine would have relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) equivalent to those of patients randomly assigned to standard chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil [CMF] or doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide [AC]).1 The results of this trial showed that standard chemotherapy was associated with a significant improvement in both RFS and OS compared with capecitabine, but the toxicity profiles of the three regimens varied, with capecitabine being less toxic than either CMF or AC.1 Before initiation of the CALGB trial, smaller trials had shown that capecitabine had similar efficacy to both paclitaxel and CMF in the metastatic setting,2,3 leading to our testing it as a single agent in older adults in the adjuvant setting. Assuming that we found similar disease-free survival and OS for standard chemotherapy and capecitabine, but better quality of life (QoL) with capecitabine in the preplanned QoL substudy, the results would have helped in treatment recommendations.

The primary objective of the QoL substudy was to compare the QoL of patients treated by standard chemotherapy with the QoL of those treated by capecitabine over time. The primary end points for QoL were the global subscale from the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) version 3.0 core QoL measure,4 the systemic adverse effects subscale of the EORTC breast module (EORTC BR23),5 and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),6 at midtreatment, end of treatment, and 12 months.

Our hypothesis was that there would be better QoL in capecitabine-treated patients at midtreatment and end of treatment, possibly because of less toxicity and the preference of patients for oral chemotherapy. We also hypothesized that the potentially increased toxicity of standard chemotherapy affecting global QoL, systemic adverse effects, and psychological state (the three primary end points) at midtreatment and end of treatment would be resolved by 12 months, since patients would have completed therapy at about 6 months. To gain a greater understanding of the potential reasons for the QοL differences, secondary end points involving additional physical symptoms and patient functioning were included.5

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Research Procedures

Patients had to meet the eligibility criteria for the parent clinical trial (CALGB 49907): age 65 years or older, diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer (stages I to III), tumor size larger than 1 cm, performance status of 0 to 2 (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] criteria), and expected survival > 5 years. The detailed eligibility criteria have been published.1 For the QoL component, patients could be English- or Spanish-speaking and were eligible if they had cognitive and psychological functioning sufficient for providing informed consent and participation in the trial.

Clinical research associates asked all consecutive English- and Spanish-speaking patients who were offered participation in CALGB 49907 if they also wanted to participate in the QoL study until the required number of 350 patients was accrued, as determined by the statistical plan. Some patients refused participation in the QoL study. Two hundred eighty patients (140 per group) were required at the end of 12 months to detect a difference of 0.43 standard deviations in standardized means in the primary QoL end points between standard chemotherapy and capecitabine patients with a power of 0.85 at an α level of .01, using two-sided two-sample t tests. Assuming an attrition rate of 20% during the first year, an accrual objective of 350 patients was set.

Patients who consented to participate were given a packet of QoL questionnaires to complete before the telephone interview, at which time the centralized research interviewer collected their answers. Patients were assessed at baseline, midtreatment (CMF, approximately day 77; for AC, approximately day 29; for capecitabine, approximately day 63), post-treatment (within 1 month of completion of chemotherapy; for CMF, 6 to 7 months; for AC, 4 to 5 months; for capecitabine, 4 to 5 months), and at 12, 18, and 24 months postbaseline. The rationale for following patients over a 24-month period was that 24 months was considered to be a sufficient amount of time for testing whether any toxicity and its resultant effects on functioning would continue past the 6-month period at which time all treatment had ended. These assessment points follow the timing of the regimens. CMF therapy consisted of cyclophosphamide administered orally from days 1 through 14 and methotrexate and fluorouracil administered intravenously on days 1 and 8; the cycle was repeated every 28 days for a total of six cycles. AC was administered intravenously on day 1; the cycle was repeated every 21 days for four cycles. Capecitabine was administered orally for 14 consecutive days every 3 weeks, for a total of six cycles. A more detailed description of the treatment regimens has been published.1 In accordance with the institutional review boards of their institutions, patients accrued to the clinical trial provided written informed consent.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures included the primary end points of overall QoL, systemic adverse effects, and psychological state as measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0),4 the systemic adverse effects subscale of the EORTC BR23,5 and the HADS,6,7 respectively. The secondary end points were physical symptoms and physical, role, social, emotional, and cognitive functioning (EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC BR23, Hand-Foot Syndrome scale [developed by the authors], and the Neurobehavioral Functioning Scale [developed by Sakin et al8]).

The core QoL measure (EORTC QLQ-C30, version 3.0),4 consisting of 30 items, and the breast cancer module (EORTC BR23),5 consisting of 23 items specific to breast cancer, assessed patients' global QoL, physical symptoms, and physical, role, social, and emotional functioning. All scores were transformed to a scale of 0 to 100, with higher scores of functioning indicating greater functioning, and higher scores on symptoms indicating worse symptoms. The HADS,6 consisting of 14 items, assessed anxiety and depression, with a cutoff score of ≥ 15 on the total score7 indicating clinically important anxiety and depression. Psychosocial services for emotional or family problems that the patient had used since diagnosis and was using at the time of the interview were assessed by two items from the Caregiver Burden Interview.9 Cognitive impairment was assessed by items that measured attention (selective concentration on one object while ignoring others), problem-solving (processes involved in solving problems for a specific situation), speed (speed by which one processes information), new learning (knowledge or skill gained through study or experience), prospective memory (remembering to perform an intended action), and remote memory (memory of years ago) in 18 items from the Neurobehavioral Functioning and Activities of Living Scale.8 All items ranged from 1 (above-average ability) to 7 (severe problems), with total mean scores for each subscale and total score ranging from 1 to 7. Treatment-related toxicity was graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria scales.10 The authors created a study-specific scale to assess hand-foot syndrome that used three self-rated items—pain, swelling, and skin changes in hands or feet—and a four-point scale, with higher scores indicating worse symptoms. Zero indicated no toxicity; 1, minimal symptoms and no functional loss; 2, moderate symptoms interfering with function; and 3, severe symptoms resulting in inability to perform activities of daily living. The Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration (BOMC) Test11 was used as an eligibility criterion for gross cognitive impairment with those scoring 11 or higher considered as having gross cognitive impairment, making them ineligible to participate in the study.

In addition, several covariates were selected that were considered to possibly interact with QoL findings, such as comorbidity and effect on function measured by a modification of the Older American Resources and Services Questionnaire (OARS).12 The OARS assesses the presence and severity of 14 medical conditions, each rated on a three-point Likert scale regarding their interference with patients' activities (0, none; 2, a great deal). A second covariate, social support, was assessed by the Medical Outcome Study (MOS) Social Support Survey,13 consisting of 20 items. Other covariates were assessed using the CALGB Background Information Form,14 which includes detailed sociodemographic information. Age and ethnicity data were obtained from the CALGB Registration Form. Clinical characteristics obtained from the medical record, including type of surgery and estrogen receptor (ER) status, were also included as covariates.

Statistical Methods

All analyses were conducted in the intent-to-treat population. The type 1 error was adjusted to 0.01 to reduce the chance of spurious significant findings. There was no formal correction for multiple comparisons. Frequency distributions and means were used to describe the patient baseline characteristics. Mean observed data were analyzed with two-sample t tests comparing the scores of patients from the standard chemotherapy and capecitabine arms at each assessment point. Fisher's exact test was used to determine whether the proportion of patients who scored 15 or higher on the HADS was associated with the treatment. The linear mixed-effects models with the nominal time to each assessment as the repeated variable and a compound symmetric covariance structure were used to assess the treatment difference in the end points over time, assuming that any missing data were missing at random. All available data for each patient were used in the analyses. The predictors were treatment, time, treatment by time interaction, age, ER status, comorbidities' interference with activities, social support, and type of surgery. The parameter estimates were obtained from the restricted maximum likelihood method. Predicted mean scores were calculated, and treatment differences were assessed for interactions between treatment group and follow-up time.

RESULTS

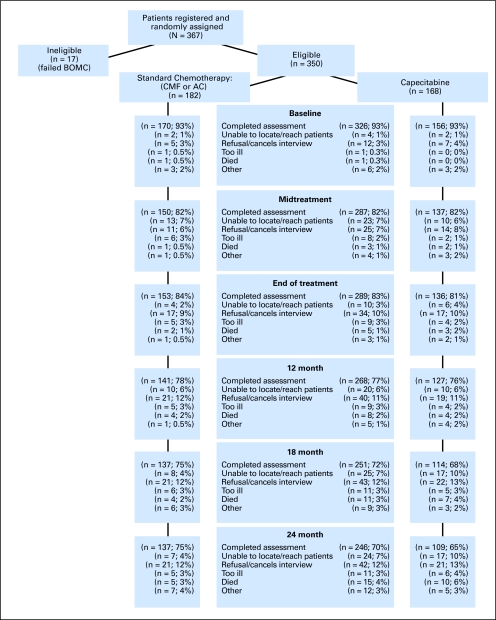

From June 2002 to April 2006, 367 patients accrued to CALGB 49907 (total accrual = 633) consented to participate in the QoL study. Seventeen of these patients were ineligible because of gross cognitive impairment resulting in 350 eligible participants in the QoL substudy: 182 in the standard chemotherapy arm and 168 in the capecitabine arm (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram shows assessment over the study period. Deaths are cumulative. Standard therapy consists of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) or doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC). Midtreatment: CMF, day 77; AC, day 29; capecitabine, day 63. End of treatment: CMF, 6-7 months; AC, 4-5 months; capecitabine, 4-5 months. BOMC, Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration test.

The average age of the participants was 72 years old (Table 1). The majority of participants in each treatment arm were white, retired, and married, with a sizable percentage in each treatment arm being widowed. Approximately half the patients in each treatment arm had a mastectomy. There were no differences among patients treated by standard chemotherapy or by capecitabine in any of the sociodemographic or clinical characteristics. There were minor differences of 1 to 2 years in age for QoL participants versus non-QoL participants and in age at diagnosis. For the total sample, completed assessments ranged from 93% at baseline to 70% at 24 months. Reasons for attrition over the course of the 2-year study period are presented in Figure 1. There were no differences in compliance with completing QoL questionnaires over time after adjusting for differences in survival time.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Standard Chemotherapy (n = 182) |

Capecitabine (n = 168) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean | 72 | 72 | ||

| SD | 4.6 | 5.0 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 157 | 86 | 144 | 86 |

| African American | 23 | 13 | 16 | 10 |

| Other | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 95 | 52 | 84 | 50 |

| Separated/divorced | 13 | 7 | 19 | 11 |

| Widowed | 48 | 26 | 43 | 26 |

| Single | 13 | 7 | 9 | 5 |

| Unknown | 13 | 7 | 13 | 8 |

| Education | ||||

| Grades 1 through 11 | 16 | 9 | 25 | 15 |

| Completed high school | 68 | 37 | 60 | 36 |

| Some college | 46 | 25 | 38 | 23 |

| College | 21 | 12 | 12 | 7 |

| Postcollege | 18 | 10 | 19 | 11 |

| Unknown | 13 | 7 | 14 | 8 |

| Employment* | ||||

| Full-time/part-time | 15 | 8 | 15 | 9 |

| Retired | 122 | 67 | 110 | 66 |

| Other | 31 | 17 | 30 | 18 |

| Unknown | 15 | 8 | 13 | 8 |

| Household composition | ||||

| Living with others | 99 | 54 | 90 | 54 |

| Living alone | 48 | 26 | 44 | 26 |

| Unknown | 35 | 19 | 34 | 20 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| 0 | 17 | 9 | 13 | 8 |

| 1 | 38 | 21 | 31 | 19 |

| 2-3 | 66 | 36 | 64 | 38 |

| 4-10 | 49 | 27 | 50 | 30 |

| Unknown | 12 | 7 | 10 | 6 |

| Performance status | ||||

| 0-1 | 177 | 97 | 160 | 95 |

| 2 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 5 |

| Tumor size, cm | ||||

| ≤ 2.0 | 82 | 45 | 63 | 37 |

| > 2-5 | 87 | 48 | 97 | 58 |

| > 5 | 12 | 7 | 8 | 5 |

| Mean | 2.7 | 2.7 | ||

| SD | 1.5 | 1.5 | ||

| No. of positive nodes | ||||

| None | 53 | 29 | 51 | 30 |

| 1-3 | 100 | 55 | 91 | 54 |

| 4+ | 28 | 15 | 26 | 16 |

| Mean | 1.97 | 1.8 | ||

| SD | 2.5 | 2.5 | ||

| PgR status | ||||

| Negative | 85 | 47 | 83 | 49 |

| Positive | 96 | 53 | 85 | 51 |

| ER status | ||||

| Negative | 65 | 36 | 55 | 33 |

| Positive | 117 | 64 | 113 | 67 |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Partial mastectomy/ lumpectomy/ excisional biopsy | 77 | 42 | 81 | 48 |

| Mastectomy, NOS | 104 | 57 | 86 | 51 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; PgR, progesterone receptor; ER, estrogen receptor; NOS, not otherwise stated.

Allows for more than one response.

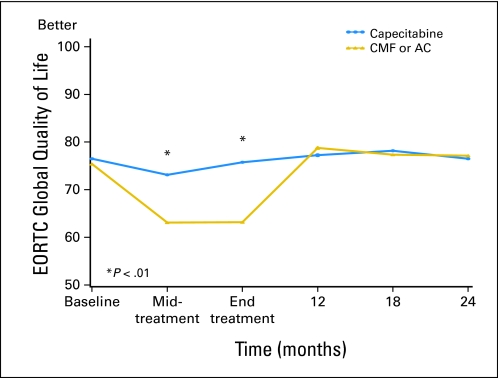

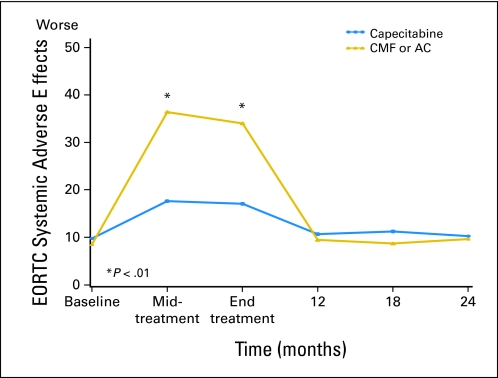

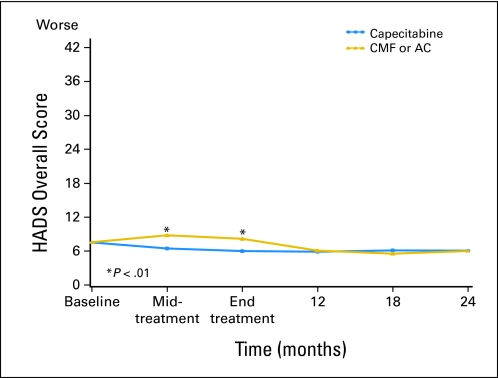

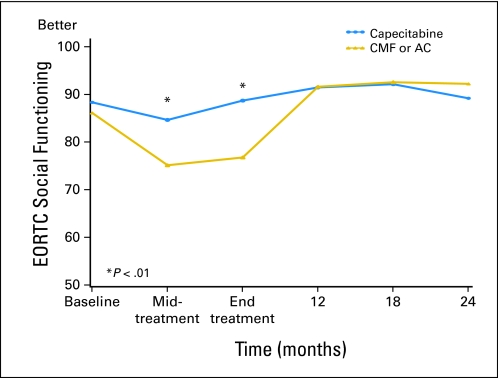

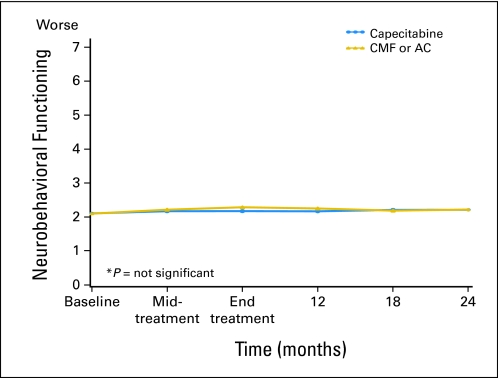

Linear mixed-effects models were used to investigate whether QoL was better in patients treated with capecitabine than in those treated with standard chemotherapy. The predicted means in Table 2 (primary end points) and Appendix Table A1 (online only; secondary end points) and Figures 2, 3, and 4 and Appendix Figures A1-A4 (online only) were adjusted for the potential confounders of age, ER status, comorbidities, interference with activities, social support, and type of surgery. Treatment differences were assessed for interactions between treatment groups, and follow-up time since the tests for treatment by time interaction were significant for all primary and most secondary end points. Patients treated with capecitabine had a significantly better global QoL score at midtreatment (P < .001) and end of treatment (P < .001), fewer systemic treatment-related adverse effects at midtreatment (P < .001) and end of treatment (P < .001), and a lower HADS total score at midtreatment (P < .001) and end of treatment (P < .001) than those treated by standard chemotherapy (Table 2, Figs 2–4). At midtreatment, 18.8% of patients treated by standard chemotherapy reported HADS scores ≥ 15, while only 6.5% of patients treated by capecitabine had HADS scores ≥ 15 (P = .002; Appendix Fig A5, online only). Psychosocial services were used by < 10% of patients in either arm during the 24-month study period, including midway through treatment when patients were most distressed. Patients treated with capecitabine had better EORTC role functioning (P ≤ .002) and social functioning (P < .001) and less fatigue (P < .001), less nausea and vomiting (P < .001), less constipation (P ≤ .004), and better appetite (P = .005) than patients treated with standard chemotherapy at midtreatment and/or end of treatment (Appendix Table A1). There were no significant differences in physical functioning, neurobehavioral functioning, and pain between the two treatment arms over time. Patients treated with capecitabine had significantly worse hand-foot syndrome symptoms at midtreatment and end of treatment (P < .001) and worse diarrhea at midtreatment (P = .005) than patients treated with standard chemotherapy. The significantly better QoL of patients treated with capecitabine compared with patients treated with standard chemotherapy, observed at midtreatment and end of treatment, was no longer present at 12 months, and there were no further differences at 24 months. The longitudinal analyses with linear mixed-effects models (Table 2 and Appendix Table A1) showed similar patterns compared with the observed mean scores (Appendix Table A2, online only).

Table 2.

QoL Variables by Treatment Arm Over Time for Primary Objectives (linear mixed-effects models)

| Assessment | Standard Chemotherapy* |

Capecitabine† |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Score | SE | Mean Score | SE | ||

| Overall QoL (EORTC QLQ-C30)‡ | |||||

| Baseline | 75.4 | 1.4 | 76.5 | 1.5 | .587 |

| Midtreatment | 63.1 | 1.5 | 73.1 | 1.5 | < .001 |

| End of treatment | 63.2 | 1.4 | 75.8 | 1.5 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 78.8 | 1.5 | 77.3 | 1.6 | .481 |

| 18 months | 77.4 | 1.5 | 78.2 | 1.6 | .708 |

| 24 months | 77.2 | 1.5 | 76.5 | 1.7 | .775 |

| Systemic adverse effects (EORTC BR23)§ | |||||

| Baseline | 8.5 | 1.1 | 9.8 | 1.1 | .407 |

| Midtreatment | 36.4 | 1.1 | 17.6 | 1.1 | < .001 |

| End of treatment | 34.0 | 1.0 | 17.1 | 1.1 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 9.5 | 1.1 | 10.7 | 1.2 | .451 |

| 18 months | 8.7 | 1.1 | 11.3 | 1.2 | .126 |

| 24 months | 9.7 | 1.1 | 10.3 | 1.2 | .715 |

| HADS total§ | |||||

| Baseline | 7.6 | 0.4 | 7.5 | 0.4 | .947 |

| Midtreatment | 8.8 | 0.4 | 6.5 | 0.4 | < .001 |

| End of treatment | 8.2 | 0.4 | 6.0 | 0.4 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 6.1 | 0.4 | 5.9 | 0.4 | .746 |

| 18 months | 5.6 | 0.4 | 6.1 | 0.4 | .348 |

| 24 months | 6.0 | 0.4 | 6.1 | 0.5 | .915 |

NOTE. Covariates are treatment, assessment, assessment by treatment interaction, age, estrogen receptor status, comorbidities' interference with activities, social support, and type of surgery.

Abbreviations: QoL, quality of life; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30; EORTC BR23, an EORTC breast module; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

For standard treatment with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC): midtreatment, day 29; end of treatment, 4-5 months; for treatment with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF): midtreatment, day 77; end of treatment, 6-7 months.

For treatment with capecitabine: midtreatment, day 63; end of treatment, 4-5 months.

Higher scores mean better quality of life.

Higher scores mean worse quality of life.

Fig 2.

Global quality of life (QoL) by treatment arm over time according to European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC; predicted mean scores). Standard therapy consists of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) or doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC). Midtreatment: CMF, day 77; AC, day 29; capecitabine, day 63. End of treatment: CMF, 6-7 months; AC, 4-5 months; capecitabine, 4-5 months.

Fig 3.

Systemic adverse effects by treatment arm over time according to European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC; predicted mean scores). Standard therapy consists of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) or doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC). Midtreatment: CMF, day 77; AC, day 29; capecitabine, day 63. End of treatment: CMF, 6-7 months; AC, 4-5 months; capecitabine, 4-5 months.

Fig 4.

Psychological distress by treatment arm over time according to Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; predicted mean scores). Standard therapy consists of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) or doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC). Midtreatment: CMF, day 77; AC, day 29; capecitabine, day 63. End of treatment: CMF, 6-7 months; AC, 4-5 months; capecitabine, 4-5 months.

DISCUSSION

Patients treated with capecitabine had a significantly better QoL than those treated with standard chemotherapy at midtreatment and/or end of treatment as assessed by role and social functioning, psychological state, and most physical symptoms, with all differences resolved at 12 months and with no further differences at 24 months. These data confirmed our hypothesis that QoL would be superior for patients treated with capecitabine during and at the completion of chemotherapy. This was true even though patients treated with capecitabine reported significantly more occurrences of hand-foot syndrome and diarrhea during treatment. There were no differences between the groups in pain, physical function, and neurobehavioral function. The findings of fewer systemic adverse effects, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, constipation, and better appetite in patients treated with capecitabine were in keeping with the broader toxicity results from the clinical trial in which there was less moderate to severe toxicity than in those treated with standard chemotherapy (33% v 64%, respectively).1

It is important to note that the percentage of patients treated with standard chemotherapy with clinically important anxiety and depression was almost three times that of patients treated with capecitabine at midtreatment. However, since the precise psychiatric diagnosis could not be determined by the HADS, it is possible that some of these patients might have a diagnosis of adjustment disorder, often a response to recent severe stressful events such as cancer treatment, which improves when the stimulus diminishes. In one study,15 68% of the psychiatric diagnoses in cancer patients consisted of adjustment disorders, supporting our interpretation of the findings. Our data suggest that oncologists should screen women for depression and anxiety during adjuvant chemotherapy, and consider those who screen positive for referral to psychosocial services. This is especially important given that the vast majority of patients did not obtain any mental health services during and at the end of treatment. A limitation of this study was that approximately 30% of patients were not assessed at 24 months. This finding limits our ability to generalize these results to all older breast cancer patients in CALGB 49907. However, race, tumor size, and ER status were not related to dropping out of the QoL study. Moreover, 15 patients in the QoL study died by 24 months, others had relapsed, and others had withdrawn from the study treatments. Thus, it is likely that these results would apply to a much larger sample.

The oral agent capecitabine was associated with better QoL than was standard chemotherapy at midtreatment and/or end of treatment, but these differences had resolved by 12 months with no further differences at 24 months. The parent trial for this QoL analysis, CALGB 49907, showed that at 3 years, RFS (84.7% v 67.7%; P < .001) and OS (90.6% v 86.4%; P ≤ .02) were significantly better for older breast cancer patients treated with standard chemotherapy compared with those treated with capecitabine.1 The data for this QoL trial should be reassuring to older women who are given standard therapy; although differences in QoL favored capecitabine during treatment, by 1 year these differences resolved. Since the goal of adjuvant treatment is to increase the chance for cure, these brief changes in QoL are a modest price to pay for improved survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank all of the breast cancer patients who so graciously shared their thoughts and feelings with us about their cancer treatment experience. We also thank Arti Hurria, MD, in the production of Figure 1; James Herndon II, PhD, for statistical consultation; and Jeanne F. Noe, PharmD, for help with editing the manuscript.

Appendix

The following institutions participated in this study: University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, OK, Howard Ozer, MD, supported by CA37447; Christiana Care Health Services Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP), Wilmington, DE, Stephen Grubbs, MD, supported by CA45418; Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, Harold J. Burstein, MD, supported by CA32291; Dartmouth Medical School-Norris Cotton Cancer Center, Lebanon, NH, Konstantin Dragnev, MD, supported by CA04326; Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, Jeffrey Crawford, MD, supported by CA47577; Grand Rapids Clinical Oncology Program, Grand Rapids, MI, Martin J. Bury, MD; Cancer Centers of the Carolinas, Greenville, SC, Jeffrey K. Giguere, MD, supported by CA29165; Hematology-Oncology Associates of Central New York CCOP, Syracuse, NY, Jeffrey Kirshner, MD, supported by CA45389; Illinois Oncology Research Association, Peoria, IL, John W. Kugler, MD, supported by CA35113; Long Island Jewish Medical Center, Lake Success, NY, Kanti R. Rai, MD, supported by CA35279; Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, Clifford A. Hudis, MD, supported by CA77651; Missouri Baptist Medical Center, St. Louis, MO, Alan P. Lyss, MD, supported by CA114558-02; Missouri Valley Consortium CCOP, Omaha, NE, Gamini S. Soori, MD; Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami, FL, Rogerio C. Lilenbaum, MD, supported by CA45564; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, Lewis R. Silverman, MD, supported by CA04457; Nevada Cancer Research Foundation CCOP, Las Vegas, NV, John A. Ellerton, MD, supported by CA35421; Northern Indiana Cancer Research Consortium CCOP, South Bend, IN, Rafat Ansari, MD, supported by CA86726; Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY, Ellis Levine, MD, supported by CA59518; Southeast Cancer Control Consortium CCOP, Goldsboro, NC, James N. Atkins, MD, supported by CA45808; State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, Stephen L. Graziano, MD, supported by CA21060; The Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus, OH, Clara D. Bloomfield, MD, supported by CA77658; University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA, Barbara A. Parker, MD, supported by CA11789; University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, Hedy L. Kindler, MD, supported by CA41287; University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center, Baltimore, MD, Martin Edelman, MD, supported by CA31983; University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, William V. Walsh, MD, supported by CA37135; University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, Bruce A. Peterson, MD, supported by CA16450; University of Missouri/Ellis Fischel Cancer Center, Columbia, MO, Michael C. Perry, MD, supported by CA12046; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, Thomas C. Shea, MD, supported by CA47559; University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, Steven M. Grunberg, MD, supported by CA77406; Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, David D. Hurd, MD, supported by CA03927; Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC, Brendan M. Weiss, MD, supported by CA26806; Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, Nancy Bartlett, MD, supported by CA77440; Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY, John Leonard, MD, supported by CA07968; Western Pennsylvania Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, PA, John Lister, MD.

Table A1.

QoL Variables by Treatment Arm Over Time for Secondary End Points (linear mixed-effects models)

| Assessment | Standard Chemotherapy* |

Capecitabine† |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Score | SE | Mean Score | SE | ||

| Physical functioning (EORTC QLQ-C30)‡ | |||||

| Baseline | 86.3 | 1.3 | 84.4 | 1.4 | .322 |

| Midtreatment | 76.6 | 1.4 | 78.4 | 1.4 | .362 |

| End of treatment | 74.5 | 1.3 | 79.1 | 1.4 | .019 |

| 12 months | 82.0 | 1.4 | 79.9 | 1.5 | .305 |

| 18 months | 81.4 | 1.4 | 80.9 | 1.5 | .810 |

| 24 months | 80.8 | 1.4 | 79.1 | 1.5 | .429 |

| Role functioning (EORTC QLQ-C30)‡ | |||||

| Baseline | 82.4 | 1.7 | 86.2 | 1.8 | .135 |

| Midtreatment | 70.2 | 1.8 | 78.4 | 1.9 | .002 |

| End of treatment | 72.0 | 1.8 | 84.8 | 1.9 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 89.5 | 1.9 | 87.0 | 2.0 | .361 |

| 18 months | 89.1 | 1.9 | 86.6 | 2.0 | .380 |

| 24 months | 89.3 | 1.9 | 85.4 | 2.1 | .159 |

| Social functioning (EORTC QLQ-C30)‡ | |||||

| Baseline | 86.1 | 1.6 | 88.3 | 1.6 | .319 |

| Midtreatment | 75.1 | 1.6 | 84.6 | 1.7 | < .001 |

| End of treatment | 76.7 | 1.6 | 88.7 | 1.7 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 91.6 | 1.7 | 91.4 | 1.7 | .956 |

| 18 months | 92.5 | 1.7 | 92.1 | 1.8 | .868 |

| 24 months | 92.2 | 1.7 | 89.2 | 1.8 | .222 |

| Hand-foot syndrome§ | |||||

| Baseline | 1.1 | 0.04 | 1.1 | 0.04 | .719 |

| Midtreatment | 1.2 | 0.04 | 1.8 | 0.04 | < .001 |

| End of treatment | 1.3 | 0.04 | 1.7 | 0.04 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 1.2 | 0.04 | 1.2 | 0.04 | .791 |

| 18 months | 1.3 | 0.04 | 1.2 | 0.04 | .685 |

| 24 months | 1.2 | 0.04 | 1.2 | 0.04 | .443 |

| Neurobehavioral functioning§ | |||||

| Baseline | 2.1 | 0.05 | 2.1 | 0.05 | .901 |

| Midtreatment | 2.2 | 0.05 | 2.2 | 0.05 | .499 |

| End of treatment | 2.3 | 0.05 | 2.2 | 0.05 | .094 |

| 12 months | 2.2 | 0.05 | 2.2 | 0.05 | .232 |

| 18 months | 2.2 | 0.05 | 2.2 | 0.05 | .743 |

| 24 months | 2.2 | 0.05 | 2.2 | 0.05 | .916 |

| Fatigue (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||

| Baseline | 26.1 | 1.5 | 24.0 | 1.6 | .338 |

| Midtreatment | 44.0 | 1.6 | 35.0 | 1.7 | < .001 |

| End of treatment | 44.3 | 1.6 | 31.1 | 1.7 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 25.5 | 1.6 | 25.0 | 1.7 | .857 |

| 18 months | 25.0 | 1.6 | 25.3 | 1.8 | .889 |

| 24 months | 24.0 | 1.6 | 25.9 | 1.8 | .435 |

| Pain (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||

| Baseline | 21.2 | 1.7 | 19.2 | 1.8 | .412 |

| Midtreatment | 19.3 | 1.8 | 21.0 | 1.9 | .503 |

| End of treatment | 16.5 | 1.8 | 20.5 | 1.9 | .115 |

| 12 months | 20.9 | 1.8 | 21.9 | 1.9 | .686 |

| 18 months | 18.9 | 1.8 | 18.3 | 1.9 | .829 |

| 24 months | 19.2 | 1.8 | 21.2 | 2.0 | .483 |

| Nausea and vomiting (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||

| Baseline | 3.5 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 0.9 | .415 |

| Midtreatment | 14.5 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 1.0 | < .001 |

| End of treatment | 11.8 | 0.9 | 5.3 | 1.0 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 1.6 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 1.0 | .072 |

| 18 months | 1.4 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 1.1 | .129 |

| 24 months | 3.0 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 1.1 | .685 |

| Constipation (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||

| Baseline | 12.3 | 1.8 | 16.3 | 1.9 | .123 |

| Midtreatment | 21.9 | 1.9 | 13.9 | 2.0 | .004 |

| End of treatment | 24.8 | 1.9 | 13.9 | 2.0 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 12.1 | 1.9 | 12.8 | 2.0 | .804 |

| 18 months | 11.2 | 1.9 | 12.3 | 2.0 | .699 |

| 24 months | 13.5 | 1.9 | 15.8 | 2.0 | .428 |

| Appetite (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||

| Baseline | 9.1 | 1.7 | 9.5 | 1.8 | .857 |

| Midtreatment | 31.8 | 1.8 | 17.9 | 1.9 | < .001 |

| End of treatment | 24.9 | 1.8 | 12.5 | 1.9 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 6.8 | 1.8 | 9.6 | 1.9 | .291 |

| 18 months | 4.4 | 1.8 | 8.2 | 2.0 | .161 |

| 24 months | 7.2 | 1.8 | 9.2 | 2.0 | .467 |

| Diarrhea (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||

| Baseline | 5.0 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 1.5 | .995 |

| Midtreatment | 14.0 | 1.5 | 19.9 | 1.5 | .005 |

| End of treatment | 15.2 | 1.5 | 13.1 | 1.5 | .313 |

| 12 months | 5.0 | 1.5 | 6.5 | 1.6 | .489 |

| 18 months | 5.1 | 1.5 | 6.9 | 1.7 | .425 |

| 24 months | 7.1 | 1.5 | 8.0 | 1.7 | .699 |

NOTE. Covariates are treatment, assessment, assessment by treatment interaction, age, estrogen receptor status, comorbidities' interference with activities, social support, and type of surgery.

Abbreviations: QoL, quality of life; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30.

For standard treatment with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC): midtreatment, day 29; end of treatment, 4-5 months; for treatment with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF): midtreatment, day 77; end of treatment, 6-7 months.

For treatment with capecitabine: midtreatment, day 63; end of treatment, 4-5 months.

Higher scores mean better quality of life.

Higher scores mean worse quality of life.

Table A2.

QoL Variables by Treatment Arm Over Time (observed mean scores, ttests)

| Assessment | Standard Chemotherapy* |

Capecitabine† |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | Mean Score | SE | No. of Patients | Mean Score | SE | ||

| Primary outcomes | |||||||

| Overall QoL (EORTC QLQ-C30)‡ | |||||||

| Baseline | 168 | 74.9 | 1.7 | 157 | 76.3 | 1.6 | .557 |

| Midtreatment | 147 | 64.0 | 1.8 | 137 | 73.6 | 1.7 | .001 |

| End of treatment | 153 | 63.9 | 1.7 | 135 | 76.1 | 1.5 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 140 | 79.2 | 1.4 | 126 | 78.0 | 1.6 | .588 |

| 18 months | 135 | 76.5 | 1.5 | 113 | 78.7 | 1.6 | .334 |

| 24 months | 136 | 77.2 | 1.5 | 109 | 78.2 | 1.9 | .666 |

| Systemic adverse effects§ | |||||||

| Baseline | 150 | 8.7 | 0.8 | 138 | 9.9 | 0.8 | .345 |

| Midtreatment | 147 | 36.6 | 1.5 | 129 | 17.3 | 1.2 | .028 |

| End of treatment | 150 | 33.9 | 1.5 | 132 | 16.8 | 1.2 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 117 | 10.8 | 1.1 | 127 | 10.1 | 1.0 | .629 |

| 18 months | 127 | 9.2 | 0.9 | 107 | 11.4 | 1.3 | .190 |

| 24 months | 126 | 10.8 | 1.0 | 101 | 10.0 | 1.1 | .591 |

| HADS total§ | |||||||

| Baseline | 170 | 7.5 | 0.3 | 158 | 7.5 | 0.4 | .959 |

| Midtreatment | 149 | 8.6 | 0.5 | 138 | 6.4 | 0.5 | .002 |

| End of treatment | 153 | 8.3 | 0.5 | 136 | 6.0 | 0.5 | .001 |

| 12 months | 141 | 6.1 | 0.5 | 127 | 6.0 | 0.5 | .905 |

| 18 months | 137 | 5.9 | 0.4 | 114 | 6.4 | 0.5 | .516 |

| 24 months | 137 | 6.3 | 0.5 | 109 | 6.0 | 0.5 | .676 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||

| Physical functioning (EORTC QLQ-C30)‡ | |||||||

| Baseline | 165 | 86.2 | 1.3 | 156 | 84.2 | 1.3 | .292 |

| Midtreatment | 149 | 77.0 | 1.6 | 137 | 78.8 | 1.7 | .437 |

| End of treatment | 153 | 74.9 | 1.6 | 133 | 79.8 | 1.5 | .027 |

| 12 months | 141 | 82.1 | 1.5 | 126 | 80.5 | 1.7 | .460 |

| 18 months | 137 | 81.3 | 1.6 | 113 | 81.2 | 1.7 | .963 |

| 24 months | 136 | 80.3 | 1.6 | 109 | 80.5 | 2.0 | .920 |

| Role functioning (EORTC QLQ-C30)‡ | |||||||

| Baseline | 164 | 82.0 | 1.9 | 157 | 86.1 | 1.5 | .087 |

| Midtreatment | 147 | 70.5 | 2.3 | 136 | 78.9 | 2.4 | .013 |

| End of treatment | 150 | 72.6 | 2.0 | 132 | 85.0 | 2.0 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 141 | 89.6 | 1.6 | 125 | 86.7 | 2.1 | .264 |

| 18 months | 135 | 88.9 | 1.6 | 113 | 86.5 | 2.3 | .368 |

| 24 months | 137 | 88.6 | 1.7 | 109 | 86.3 | 2.3 | .410 |

| Social functioning (EORTC QLQ-C30)‡ | |||||||

| Baseline | 164 | 85.6 | 1.2 | 153 | 88.1 | 1.4 | .252 |

| Midtreatment | 146 | 75.3 | 2.2 | 135 | 84.5 | 2.0 | .002 |

| End of treatment | 149 | 76.6 | 1.9 | 132 | 88.9 | 2.1 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 137 | 91.4 | 1.5 | 124 | 91.3 | 1.6 | .958 |

| 18 months | 136 | 91.7 | 1.4 | 113 | 91.2 | 1.6 | .802 |

| 24 months | 136 | 91.2 | 1.6 | 109 | 89.6 | 2.1 | .546 |

| Hand-foot syndrome§ | |||||||

| Baseline | 99 | 1.1 | 0.03 | 113 | 1.1 | 0.02 | .435 |

| Midtreatment | 149 | 1.2 | 0.03 | 137 | 1.8 | 0.06 | < .001 |

| End of treatment | 153 | 1.3 | 0.03 | 136 | 1.7 | 0.07 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 140 | 1.2 | 0.03 | 126 | 1.2 | 0.04 | .810 |

| 18 months | 138 | 1.3 | 0.03 | 114 | 1.2 | 0.04 | .45 |

| 24 months | 136 | 1.2 | 0.04 | 109 | 1.2 | 0.04 | .173 |

| Neurobehavioral functioning§ | |||||||

| Baseline | 165 | 2.1 | 0.04 | 156 | 2.1 | 0.05 | .807 |

| Midtreatment | 149 | 2.2 | 0.04 | 136 | 2.1 | 0.05 | .182 |

| End of treatment | 152 | 2.3 | 0.05 | 136 | 2.1 | 0.06 | .061 |

| 12 months | 141 | 2.2 | 0.05 | 127 | 2.1 | 0.06 | .188 |

| 18 months | 138 | 2.2 | 0.04 | 114 | 2.2 | 0.07 | .812 |

| 24 months | 137 | 1.2 | 0.04 | 109 | 2.2 | 0.07 | .710 |

| Fatigue (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||||

| Baseline | 164 | 26.4 | 1.5 | 154 | 24.3 | 1.5 | .303 |

| Midtreatment | 145 | 43.2 | 2.0 | 135 | 34.8 | 2.0 | .003 |

| End of treatment | 152 | 43.7 | 1.8 | 133 | 30.9 | 1.9 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 141 | 25.5 | 1.5 | 124 | 24.7 | 1.9 | .757 |

| 18 months | 137 | 25.6 | 1.3 | 113 | 25.1 | 2.1 | .849 |

| 24 months | 137 | 24.6 | 1.5 | 108 | 24.6 | 2.1 | .996 |

| Pain (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||||

| Baseline | 166 | 21.5 | 1.7 | 156 | 19.2 | 1.6 | .336 |

| Midtreatment | 146 | 18.7 | 1.7 | 135 | 20.9 | 2.1 | .413 |

| End of treatment | 150 | 15.8 | 1.6 | 132 | 20.5 | 2.2 | .083 |

| 12 months | 139 | 20.7 | 1.9 | 125 | 21.9 | 2.3 | .664 |

| 18 months | 136 | 19.1 | 1.9 | 113 | 18.5 | 2.1 | .822 |

| 24 months | 135 | 19.3 | 2.0 | 107 | 20.2 | 2.6 | .781 |

| Nausea and vomiting (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||||

| Baseline | 165 | 3.9 | 0.7 | 154 | 2.6 | 0.7 | .175 |

| Midtreatment | 146 | 14.6 | 1.3 | 134 | 8.6 | 1.3 | .005 |

| End of treatment | 150 | 11.7 | 1.2 | 134 | 5.1 | 0.9 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 140 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 123 | 3.6 | 0.7 | .011 |

| 18 months | 136 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 111 | 3.1 | 1.1 | .241 |

| 24 months | 135 | 2.9 | 0.9 | 108 | 1.7 | 0.5 | .229 |

| Constipation (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||||

| Baseline | 166 | 13.0 | 1.7 | 156 | 16.4 | 2.0 | .189 |

| Midtreatment | 147 | 21.2 | 2.2 | 137 | 13.1 | 1.8 | .005 |

| End of treatment | 150 | 24.4 | 2.4 | 135 | 13.0 | 2.1 | .001 |

| 12 months | 140 | 11.9 | 1.8 | 125 | 11.7 | 1.8 | .941 |

| 18 months | 137 | 10.9 | 1.7 | 113 | 11.2 | 1.9 | .909 |

| 24 months | 136 | 13.9 | 2.0 | 109 | 14.6 | 2.1 | .818 |

| Appetite (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||||

| Baseline | 166 | 9.6 | 1.3 | 152 | 9.6 | 1.6 | .990 |

| Midtreatment | 149 | 31.7 | 2.7 | 136 | 17.4 | 2.3 | < .001 |

| End of treatment | 152 | 24.9 | 2.3 | 132 | 12.1 | 1.9 | < .001 |

| 12 months | 141 | 6.8 | 1.3 | 124 | 8.3 | 1.6 | .476 |

| 18 months | 135 | 5.2 | 1.4 | 112 | 6.8 | 1.6 | .440 |

| 24 months | 136 | 7.8 | 1.4 | 109 | 7.3 | 2.0 | .845 |

| Diarrhea (EORTC QLQ-C30)§ | |||||||

| Baseline | 168 | 4.9 | 1.0 | 156 | 5.5 | 1.1 | .690 |

| Midtreatment | 148 | 13.0 | 1.9 | 136 | 19.8 | 2.4 | .030 |

| End of treatment | 152 | 14.6 | 1.9 | 135 | 13.0 | 1.7 | .527 |

| 12 months | 141 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 125 | 6.1 | 1.1 | .236 |

| 18 months | 137 | 5.1 | 1.1 | 112 | 6.2 | 1.6 | .560 |

| 24 months | 137 | 7.3 | 1.5 | 108 | 7.7 | 1.5 | .853 |

Abbreviations: QoL, quality of life; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

For standard treatment with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC): midtreatment, day 29; end of treatment, 4-5 months; for treatment with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF): midtreatment, day 77; end of treatment, 6-7 months.

For treatment with capecitabine: midtreatment, day 63; end of treatment, 4-5 months.

Higher scores mean better quality of life.

Higher scores mean worse quality of life.

Fig A1.

Fatigue by treatment arm over time according to European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC; predicted mean scores). Standard therapy consists of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) or doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC). Midtreatment: CMF, day 77; AC, day 29; capecitabine, day 63. End of treatment: CMF, 6-7 months; AC, 4-5 months; capecitabine, 4-5 months.

Fig A2.

Role functioning by treatment arm over time according to European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC; predicted mean scores). Standard therapy consists of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) or doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC). Midtreatment: CMF, day 77; AC, day 29; capecitabine, day 63. End of treatment: CMF, 6-7 months; AC, 4-5 months; capecitabine, 4-5 months.

Fig A3.

Social functioning by treatment arm over time according to European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC; predicted mean scores). Standard therapy consists of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) or doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC). Midtreatment: CMF, day 77; AC, day 29; capecitabine, day 63. End of treatment: CMF, 6-7 months; AC, 4-5 months; capecitabine, 4-5 months.

Fig A4.

Neurobehavioral functioning by treatment arm over time according to Neurobehavioral Functioning and Activities of Living Scale (predicted mean scores). Standard therapy consists of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) or doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC). Midtreatment: CMF, day 77; AC, day 29; capecitabine, day 63. End of treatment: CMF, 6-7 months; AC, 4-5 months; capecitabine, 4-5 months.

Fig A5.

Clinically important psychological problems by treatment arm over time. Percent of patients with Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) score > 15. Standard therapy consists of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) or doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC). Midtreatment: CMF, day 77; AC, day 29; capecitabine, day 63. End of treatment: CMF, 6-7 months; AC, 4-5 months; capecitabine, 4-5 months.

Footnotes

Written on behalf of Cancer and Leukemia Group B.

Supported in part by Grants No. CA31946 from the National Cancer Institute to Cancer and Leukemia Group B, No. CA33601 to the CALGB Statistical Center, No. P30-AG-028716 from the National Institute on Aging to the Duke Claude Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, and No. U10CA85850 from the National Institute on Aging, along with Grants No. CA32291, CA33601, CA47577, CA77651, and CA77406 from the National Cancer Institute.

Presented as a poster at the 32nd Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 9-12, 2009, San Antonio, TX.

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00024102.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Clifford Hudis, Roche; Hyman B. Muss, Roche (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Gretchen Kimmick, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Novartis Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Alice B. Kornblith, Gretchen Kimmick, Clifford Hudis, Eric Winer, Harvey Jay Cohen, Hyman B. Muss

Financial support: Clifford Hudis

Administrative support: Alice B. Kornblith, Ann Partridge, Clifford Hudis, Samantha Bennett

Provision of study materials or patients: Alice B. Kornblith, Ann Partridge, Gretchen Kimmick, Clifford Hudis, Hyman B. Muss

Collection and assembly of data: Lan Lan, Laura Archer, Clifford Hudis, Rebecca Casey, Samantha Bennett, Hyman B. Muss

Data analysis and interpretation: Alice B. Kornblith, Lan Lan, Laura Archer, Ann Partridge, Gretchen Kimmick, Clifford Hudis, Harvey Jay Cohen, Hyman B. Muss

Manuscript writing: Alice B. Kornblith, Lan Lan, Laura Archer, Ann Partridge, Gretchen Kimmick, Clifford Hudis, Eric Winer, Rebecca Casey, Samantha Bennett, Harvey Jay Cohen, Hyman B. Muss

Final approval of manuscript: Alice B. Kornblith, Lan Lan, Laura Archer, Ann Partridge, Gretchen Kimmick, Clifford Hudis, Eric Winer, Rebecca Casey, Samantha Bennett, Harvey Jay Cohen, Hyman B. Muss

REFERENCES

- 1.Muss HB, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2055–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum JL, Jones SE, Buzdar AU, et al. Multicenter phase II study of capecitabine in paclitaxel-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:485–493. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oshaughnessy JA, Blum J, Moiseyenko V, et al. Randomized, open-label, phase II trial of oral capecitabine (Xeloda) vs. a reference arm of intravenous CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluououracil) as first-line therapy for advanced/metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1247–1254. doi: 10.1023/a:1012281104865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: First results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2756–2768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibbotson T, Maguire P, Selby P, et al. Screening for anxiety and depression in cancer patients: The effects of disease and treatment. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:37–40. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saykin AJ, Janssen RS, Sprehn GC, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of neuropsychologic function in homosexual men with HIV infection: 18-month follow-up. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;3:286–298. doi: 10.1176/jnp.3.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel K, Raveis VH, Mor V, et al. The relationship of spousal caregiver burden to patient disease and treatment-related conditions. Ann Oncol. 1991;2:511–516. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Cancer Institute Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Common Toxicity Criteria. 2008. http://ctep.cancer.gov/reporting/ctc.html.

- 11.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, et al. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fillenbaum GG. Hilldale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. Multidimensional Functional Assessment of Older Adults: The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services Procedures. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holland JC, Herndon J, Kornblith AB, et al. A sociodemographic data collection model for cooperative clinical trials. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1992;11(suppl):157. abstr 445. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA. 1983;249:751–757. doi: 10.1001/jama.249.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.