Abstract

To compare neural activity produced by visual events that escape or reach conscious awareness, we used event-related MRI and evoked potentials in a patient who had neglect and extinction after focal right parietal damage, but intact visual fields. This neurological disorder entails a loss of awareness for stimuli in the field contralateral to a brain lesion when stimuli are simultaneously presented on the ipsilateral side, even though early visual areas may be intact, and single contralateral stimuli may still be perceived. Functional MRI and event-related potential study were performed during a task where faces or shapes appeared in the right, left, or both fields. Unilateral stimuli produced normal responses in V1 and extrastriate areas. In bilateral events, left faces that were not perceived still activated right V1 and inferior temporal cortex and evoked nonsignificantly reduced N1 potentials, with preserved face-specific negative potentials at 170 ms. When left faces were perceived, the same stimuli produced greater activity in a distributed network of areas including right V1 and cuneus, bilateral fusiform gyri, and left parietal cortex. Also, effective connectivity between visual, parietal, and frontal areas increased during perception of faces. These results suggest that activity can occur in V1 and ventral temporal cortex without awareness, whereas coupling with dorsal parietal and frontal areas may be critical for such activity to afford conscious perception.

Right parietal damage may cause a loss of awareness for contralateral (left) sensory inputs, such as hemispatial neglect and extinction (1–3). Visual extinction is the failure to perceive a stimulus in the contralesional field when presented together with an ipsilesional stimulus (bilateral simultaneous stimulation, BSS), even though occipital visual areas are intact and unilateral contralesional stimuli can be perceived when presented alone. It reflects a deficit of spatial attention toward the contralesional side, excluding left inputs from awareness in the presence of competing stimuli (2, 3). Spatial attention involves a complex neural network centered on the right parietal lobe (4, 5), but how parietal and related areas interact with sensory processing in distant cortices is largely unknown.

Here we combined event-related functional MRI (fMRI) and event-related potentials (ERPs) to study the regional pattern and temporal course of brain activity produced by seen and unseen stimuli in a patient with chronic neglect and extinction caused by parietal damage. In keeping with intact early visual areas in such patients, behavioral studies suggest that some residual processing may still occur for contralesional stimuli without attention, or without awareness, including “preattentive” grouping (e.g., refs. 6 and 7) and semantic priming (e.g., ref. 8). It has been speculated (3, 9) that such effects might relate to separate cortical visual streams, with temporal areas extracting object features for identification, and parietal areas encoding spatial locations and parameters for action (10). Because neglect and extinction follow parietal damage, residual perceptual and semantic processing still might occur in occipital and temporal cortex without awareness, in the absence of normal integration with concomitant processing in parietal regions.

Our study tested this hypothesis by using event-related imaging and electrophysiology measures, which are widely used to study mechanisms of normal attention (11, 12). There have been few imaging (e.g., ref. 13) or ERP (e.g., ref. 14) studies in neglect, and most examined activity at rest or during passive unilateral visual stimulation, rather than in relation to awareness or extinction on bilateral stimulation. However, a recent ERP study (15) found signals evoked by perceived, but not extinguished, visual stimuli in a parietal patient. By contrast, functional imaging in another patient (16) showed activation of striate cortex by extinguished stimuli, although severe extinction on all bilateral stimuli precluded any comparison with normal perception. In our patient we used both fMRI and ERPs during a similar extinction task to determine the neural correlates of two critical conditions: (i) when contralesional stimuli are extinguished, and (ii) when the same stimuli are seen. Stimulus presentation was arranged so as to obtain a balanced number of extinguished and seen contralesional events across all bilateral trials. Like Rees et al. (16), we used face stimuli to exploit previous knowledge that face processing activates fusiform areas in temporal cortex (e.g., refs. 17 and 18), and elicits characteristic potentials 170–200 ms after stimulus onset (e.g., refs. 19–21) in addition to other visual components such as P1 and N1 (e.g., ref. 11). We reasoned that such responses might help trace the neural fate of contralesional stimuli (seen or extinguished) at both early and later processing stages in the visual system.

Methods

Patient.

CW is a 67-year-old right-handed male who had right middle cerebral artery infarct 2 years previously. He has participated in several behavioral studies (e.g., see ref. 22). Anatomical MRI scans show focal damage in the inferior posterior parietal cortex, extending into the anterior white matter of the right hemisphere (Fig. 1). Striate and extrastriate occipital cortex is intact. Neurological examination shows left-hand weakness with poor position sense, astereognosis, and left extinction on double tactile stimulation. Visual fields are full on both sides but left extinction reliably obtained on bilateral simultaneous stimulation. CW is self-independent, but shows mild left spatial neglect on standard tests (letter cancellation: 15 left misses/60 targets; line bisection: mean 6 cm rightward deviation/180-cm-long lines). No neglect is apparent on reading and mental imagery.

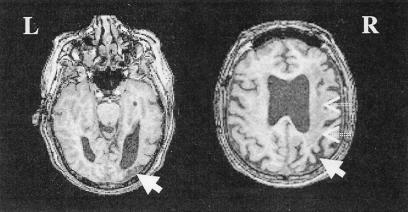

Figure 1.

Structural MRI brain scan of patient CW (axial slices), showing focal damage in inferior posterior parietal cortex (angular gyrus, thick arrows), extending into the subcortical white matter of the right hemisphere (dashed arrows).

Visual extinction was assessed in an event-related design using the same task during two fMRI sessions and two ERP sessions, all performed within a 3-month period. Separate training sessions were given before fMRI and ERP studies to ensure adequate performance with the task while maintaining central fixation.

Behavioral Task.

For both fMRI and ERPs, the stimuli comprised 10 different schematic faces and 10 different meaningless symmetrical shapes on a black background. They were presented on a computer screen during training and ERPs and reflected from a liquid crystal display projector onto a mirror inside the scanner during fMRI. Trials began with a central fixation cross (2 sec), followed by a brief stimulus in the right (RVF), left (LVF), or both visual fields (BSS). The bilateral condition (BSS) with a left face (Lf) and a right shape (Rs) provided the critical experimental trials for extinction, in which the face could be either perceived or extinguished by the patient on a given trial. BSS trials were intermixed with unilateral trials to prevent expectation biases.

The fMRI study consisted of eight runs of pseudorandomized trials (four runs in each session, 700 events in total). There were six event types: unilateral trials, including a Lf or right face (Rf) and a left shape (Ls) or Rs (n = 50 for each type in each session); blank catch trials with only the fixation cross and no stimulus in either field (Fx, n = 50 each session); and the critical bilateral trials with a Lf and a Rs (BSSfs, n = 100 each session). The ERP study included four blocks of pseudorandomized trials (total 880 events). Again, there were four possible unilateral trials with either faces (Lf and Rf, n = 30 and 30 in each block) or shapes (Ls and Rs, n = 10 and 40 in each block), as well as the same critical bilateral trials with a Lf and a Rs (BSSfs, n = 80 each block). Blank catch trials were changed to bilateral trials with a shape on both sides (BSSss, n = 30 each block). All stimuli subtended ≈2° and appeared ≈6° away from fixation. CW pressed one of two buttons (with his right hand) to indicate whether he did or did not see a face. He was instructed not to guess and to withhold from responding when unsure (3% of all BSS trials). Response buttons were aligned radially along his body midline. Average interstimulus interval was 4 sec for fMRI and 2.5 sec for ERPs.

For both fMRI and ERPs, stimulus exposure time was titrated to ensure adequate performance on unilateral trials together with a balanced number of extinguished and perceived contralesional stimuli on BSS trials (half of 20 BSS as a criterion during titration). After titration, stimulus duration was kept fixed at 250 ms for fMRI and 400 ms for ERPs. During experimental sessions, extinction rate was close to 1/2 in the ERP study and slightly greater in the fMRI study (about 2/3).

fMRI.

MRI was performed on a 1.5-T GE Signa MR scanner with a custom head coil. High-resolution T1-weighted anatomical images were collected. Functional data were acquired by using a single-shot gradient-echo spiral pulse sequence (repetition time = 2,000 ms, echo time = 40 ms), with 18 axial slices (6 mm thick, 1-mm spacing). Each session consisted of four runs of 261 scans. Motion was corrected by using AIR 3.0. Scans were realigned, normalized, and smoothed (6-mm full width, half-maximum Gaussian kernel). Data were analyzed by using the general linear model in SPM99 (23). The critical bilateral trials (BSSfs) were sorted according to perceptual report (i.e., Lf perceived or extinguished) and these two conditions separately modeled. Statistical maps resulted from linear contrasts between different trial types, thresholded at P = 0.001 (uncorrected in visual areas, corrected for the whole brain otherwise), and overlaid on coregistered anatomical images averaged across sessions. We also performed an analysis of effective connectivity (24) to detect voxels in the whole brain where activity changed as a function of the signal observed in a particular area (i.e., V1 or fusiform gyrus, defined by previous contrasts) in the context of a specific event type (i.e., perception vs. extinction of Lfs). This was done by fitting the general linear model at every voxel with two additional regressors: one being the activity at the maxima of interest (V1 or fusiform), and the second created by multiplying activity in this maxima with the difference between the regressors that modeled trials with perception versus trials with extinction. The multiplication in the second regressor represents the interaction between activity in the area of interest and the difference in awareness, and thus indicates significant changes in the coupling of any distant region with respect to activity in the area of interest on a trial-by-trial basis.

ERPs.

Continuous electroencephalogram (EEG) was recorded from 31 scalp locations using tin electrodes attached to an elastic cap, with ground and reference placed on forehead and nose, respectively (19). Additional electrodes measured horizontal and vertical electro-oculogram. EEG was sampled at 250 Hz and amplified 50,000-fold with a frequency bandpass of 0.1–40 Hz. Electrode impedance was below 5kΩ. A digital bandpass filter of 0.5–20 Hz was applied before analysis. Codes synchronized to stimulus onset were used to average epochs associated with each condition. After removing trials with eye blinks, data from the four blocks were pooled together, randomly reshuffled, and sorted into eight smaller blocks with an equal number of trials, so as to obtain repeated measures in the same subject and exclude any variance due to practice or fatigue (15). Mean amplitudes were calculated over 10-ms intervals at specific latency ranges and electrodes, relative to a 50-ms prestimulus baseline. Different conditions were compared by using ANOVA and paired t tests on average amplitudes across blocks.

Results

fMRI.

The patient correctly detected 98% of unilateral RVF stimuli and 83% of unilateral LVF stimuli. He withheld from responding on 7/200 BSS and 100/100 catch trials. He extinguished 68% of LVF faces on BSS trials [57/200 vs. 85/100 Lfs seen on bilateral vs. unilateral displays; χ2(1) = 85.4, P < 0.0001].

Hemifield and face-specific responses.

Unilateral trials were used to determine regions activated by LVF stimuli, regardless of their type, and those activated by seen faces, regardless of field. Several occipital and temporal areas (Table 1), including right primary visual cortex (V1; Fig. 2A), were activated by LVF stimulation (Lf + Ls > Rf + Rs), indicating preserved inputs to visual cortex in the damaged hemisphere. Unilateral RVF stimuli activated similar left hemisphere areas. Right inferior temporal gyrus and bilateral fusiform areas were activated by seen faces, regardless of field (Lf + Rf > Fx; Table 1 and Fig. 2B). Right anterior fusiform activity (x y z = 32 − 66 − 22) was specifically observed for faces as compared with shapes (Lf + Rf > Ls + Rs), like in normal subjects (18).

Table 1.

Regional brain activation in fMRI

| Cortical areas | Talairach

coordinates

|

T value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||

| LVF-related stimulation (Lf + Ls > Rf + Rs) | ||||

| Right striate | 4 | −78 | 8 | 3.62 |

| Right cuneus | 6 | −52 | 2 | 3.70 |

| Right inferior temporal gyrus | 48 | −64 | 6 | 3.88 |

| Right middle temporal gyrus | 64 | 0 | −2 | 4.33 |

| Left middle temporal gyrus | −68 | 0 | −6 | 4.03 |

| Face-related activation (Lf + Rf > fixation) | ||||

| Right anterior fusiform gyrus | 22 | −48 | −22 | 4.13 |

| Right posterior fusiform gyrus | 22 | −74 | −20 | 3.85 |

| Right inferior temporal gyrus | 40 | −70 | −16 | 3.97 |

| Right anterior fusiform gyrus | 32 | −66 | −22 | 3.75 |

| Left anterior fusiform gyrus | −38 | −48 | −24 | 4.51 |

| Left inferior temporal gyrus (Lf + Rf > Ls + Rs) | −40 | −70 | −22 | 4.00 |

| Right anterior fusiform gyrus | 32 | −66 | −22 | 4.01 |

| Extinguished stimuli (BSSfs ext > unilat Rs) | ||||

| Right striate | 0 | −80 | 12 | 2.56 |

| Right inferior temporal gyrus | 58 | −44 | −22 | 2.51 |

| Left inferior temporal gyrus | −48 | −38 | −20 | 2.60 |

| Perceived stimuli (BSSfs perc > BSSfs ext) | ||||

| Right striate | 8 | −94 | 0 | 3.60 |

| Right cuneus | 4 | −58 | 8 | 3.47 |

| Right cuneus | 6 | −78 | 32 | 3.25 |

| Right parahipocampal gyrus | 14 | −56 | −6 | 3.95 |

| Right anterior fusiform gyrus | 32 | −66 | −22 | 3.57 |

| Right posterior insula | 38 | −20 | −2 | 4.60 |

| Left pre-cuneus | −20 | −66 | 20 | 3.70 |

| Left fusiform gyrus | −22 | −68 | −20 | 4.69 |

| Left parietal (IPS) | −28 | −76 | 30 | 4.25 |

Note that coordinates refer to normalized space of the Talairach atlas, but anatomical areas correspond to the patient's own brain as defined from his MRI scan and do not necessarily match the same region coordinates in the Talairach atlas.

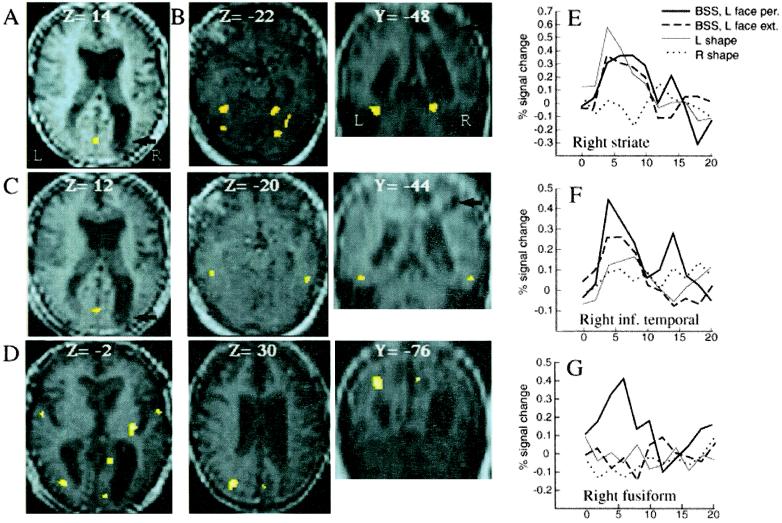

Figure 2.

(A–D) Activated areas in fMRI, superimposed on the mean brain scan across sessions (Left and Middle: axial slices; Right: coronal slices; z and y: Talairach coordinates). Damaged right parietal areas are indicated by black arrows. (A) Retinotopic activation of right V1 by unilateral LVF stimuli. (B) Bilateral activation of anterior and posterior fusiform gyri by seen faces, irrespective of field. (C) Activation of V1 (Left) and inferior temporal cortex (Middle and Right) by extinguished faces, lateral to fusiform activation by seen faces in B. (D) Distributed activation produced by seen as compared to extinguished faces in BSS, including right V1, right cuneus, right insula, and left parietal cortex (Middle and Left). (E–G) Time course of activity poststimulus onset in peak voxel (weighted by smoothing of its surround) across different conditions. (E) Right V1 voxel activated by LVF stimuli (same as A), showed similar responses to unilateral Lss and Lfs in BSS, regardless of perception or extinction, but no response to unilateral Rss. (F) Inferior temporal and (G) anterior fusiform voxels were both activated by seen faces irrespective of field (same as B and C, respectively), with the former responding to seen and extinguished faces in BSS more than to seen Lss, and the latter responding only to seen faces.

Seen and unseen faces.

The two crucial comparisons concerned the neural activity distinguishing extinction or perception of a Lf during bilateral trials. To examine the effect of unseen faces, we compared bilateral trials with an extinguished face in LVF to those with a Rs alone (BSSfs extinguished > Rs), i.e., same awareness but different stimuli in LVF. This comparison showed no significant activation at the usual statistical threshold of P = 0.001 (T = 3.09). However, lowering the threshold to P = 0.005 (T = 2.56) revealed three foci of activity: in right striate cortex (V1) and bilateral postero-inferior temporal gyri (Table 1). These temporal foci were just lateral to fusiform areas activated by seen faces (Fig. 2C).

Awareness of LVF faces was examined by comparing physically identical bilateral trials when the face was perceived and when it was not (BSSfs seen > BSSfs extinguished), i.e., same stimuli but different awareness. This revealed increased activity in several areas of both hemispheres (Table 1 and Fig. 2D), including right V1, bilateral cuneus, both fusiform gyri, and superior parietal cortex in the intact left hemisphere (intraparietal sulcus). Fig. 2 E–G shows the time course of activity in peak voxels of interest across different conditions. Right V1 showed similar activity to seen and unseen faces in LVF, but no activity when no stimulus was present. By contrast, whereas both the fusiform and inferior temporal gyri responded to seen faces (Table 1), only the latter was active when faces were extinguished.

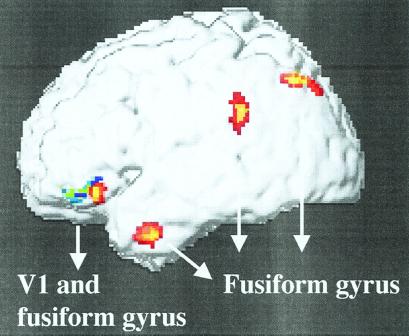

Finally, we tested for changes in effective connectivity between areas depending on awareness of LVF faces. A first analysis looked for voxels showing trial-specific increases that were coupled with the change of activity found in right V1 during perception as compared with extinction of a Lf (BSSfs seen > BSSfs extinguished). Two clusters in left inferior frontal cortex (−48 30 −4, T = 4.01; −46 24 −22, T = 3.73; P < 0.0001) showed such an increase, indicating a specific interaction between V1 and frontal areas during trials with awareness (Fig. 3). A second analysis looked for voxels showing increases coupled with left fusiform activity during perception versus extinction of faces. Such changes were found again in left frontal cortex (−46 32 −10, T = 4.15; −44 48 −8, T = 4.05), as well as in inferior and superior left parietal cortex (−66 −42 28, T = 4.18; −34 −72 46, T = 4.04), and anterior left temporal cortex (−54 6 −32, T = 4.43; P < 0.0001 in all cases). The superior parietal activation was close to the peak obtained by contrasting seen vs. extinguished stimuli (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Changes in effective connectivity on bilateral trials when LVF faces were seen as compared with extinguished. Increased activity in striate cortex covaried with increases in inferior left frontal gyrus (blue-to-green foci), whereas increased fusiform activity covaried with increases in similar frontal regions, as well as in superior and inferior parietal cortex, and anterior temporal cortex (red-to-yellow foci).

ERPs.

The patient reported 97% and 96% of unilateral stimuli in RVF and LVF, respectively. He extinguished 40% of LVF faces in critical BSSfs trials [115/120 vs. 192/320 faces seen in unilateral vs. bilateral displays; χ2(1) = 53.1, P < 0.0001]. He made only one false alarm in reporting a face of 120 displays with bilateral shapes.

Hemifield and face-specific responses.

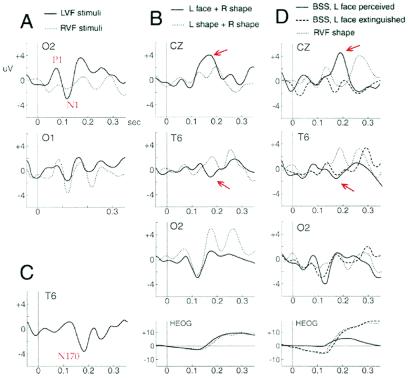

Unilateral trials were used to assess responses to perceived stimuli, regardless of their type. Contralesional stimuli (Lf + Ls) elicited early components at right occipital sites, with a positive waveform at ≈80 ms postonset (P1) and a negative waveform at ≈130 ms (N1) (Fig. 4A). ANOVA of P1 and N1 amplitudes with the factors hemisphere (right vs. left), field (contralateral vs ipsilateral), and stimuli (face vs. shape) revealed an interaction of field and hemisphere [P1: F(1,62) = 6.33, P = 0.015; N1: F(1,62) = 7.95, P = 0.006], but no other effect or interaction. Contralateral field P1 and N1 showed no hemispheric difference [F(1,30) = 2.14, P = 0.15]; right occipital responses to LVF stimuli were similar to left occipital responses to RVF stimuli [paired comparison across blocks, P1: t(7) = 1.21, P = 0.27; N1: t(7) = 1.60, P = 0.15]. This result is consistent with intact LVF input into right extrastriate areas (11). By contrast, ipsilateral field P1 and N1 showed a significant effect of hemisphere [P1: F(1,30) = 4.83, P = 0.04; N1: F(1,30) = 5.16, P = 0.03], with decreased responses on the damaged side. This finding might reflect abnormal callosal transfer, as previously found in neglect (15). Responses specific to faces in the LVF also were examined, by comparing all bilateral trials with a Lf (BSSfs) vs. Ls (BSSss), regardless of perception. Although early components did not differ, LVF faces produced a negative wave ≈170–180 ms postonset in right posterior temporal regions (Fig. 4B), consistent with the latency and location of face-selective signals in normals (N170, e.g., ref. 19). This negativity was replaced by a positivity with shapes in LVF, with a reliable difference at electrode T6 [F(1,14) = 8.58, P = 0.01], clearly shown by the face-specific waveform obtained by subtraction (Fig. 4C). In addition, a midline positivity was evoked by faces but not shapes ≈190–200 ms postonset (P190).

Figure 4.

ERPs at right occipital (O2), left occipital (O1), right posterior temporal (T6), and midline electrodes (CZ) for different conditions during 300-ms poststimulus onset. (A) Unilateral stimuli (faces and shapes) in RVF and LVF evoked an early contralateral occipital positivity at ≈80 ms (P1) and negativity at ≈120 ms (N1). (B) Lfs in bilateral trials (BSSfs) as opposed to Lss (BSSss) evoked a specific negativity at right posterior temporal site (≈170 ms postonset) and a positivity at midline (≈190 ms postonset), but similar occipital N1 (regardless of perception, as in averaged ERPs shown here). Eye movements (HEOG) were similar and cannot explain this ERP difference. (C) Difference waveform obtained by subtracting ERPs to Lfs from ERPs to Lss in BSS, clearly showing a face-specific negativity in right temporal region (N170). (D) Perception versus extinction. Compared with a Rs alone (Rs), bilateral stimuli with a LVF face (BSSfs) evoked a right occipital N1 and a temporal N170, both when the face was seen and when it was extinguished. Eye movements were similar during Rs and extinction trials and cannot explain this ERP difference. A later positivity at midline (≈190 ms postonset) occurred only when faces were seen (P190). Oculographic differences after ≈200 ms might partly contribute to this signal.

Seen and unseen faces.

Again, the crucial comparisons concerned signals associated with extinction or perception of faces. Compared with RVF shapes alone (Rs), bilateral trials with a LVF face (BSSfs) evoked a larger right occipital N1 when the face was seen, nonsignificantly reduced when the face was extinguished (Fig. 4D). ANOVA showed marginal effect of condition (Rs, BSSfs extinguished, BSSfs seen) on right occipital P1 [F(2,21) = 3.2, P = 0.06] but not N1 amplitude [F(2,21) < 1]. However, planned comparisons indicated greater N1 with faces in LVF (seen or extinguished) as compared with Rs [t(7) = 2.30 and 2.35, respectively, P = 0.05], but no difference between seen and extinguished faces [t(7) = 1.48, P = 0.18]. Compared with Rs alone, a right occipital P1 occurred with seen faces [t(7) = 2.66, P = 0.03] but not with extinction [t(7) = 1.68, P = 0.14], although the difference between these two conditions was not significant [t(7) = 0.43].

In critical BSSfs trials, there was a similar negativity at 170–180 ms in the right posterior temporal region when the face was seen and when it was extinguished (Fig. 4D), replaced by a positive wave with a RVF shape alone. T6 electrode amplitudes around 170 ms showed a main effect of condition [F(2,21) = 6.82, P = 0.005], with a reliable difference between Rs alone and seen or extinguished faces in BSSfs [t(7) = 2.86 and 3.14, respectively, P = 0.02], but no difference between seen and extinguished trials [t(7) = 1.23, P = 0.26]. Eye movements were similar on extinction and unilateral right trials (Fig. 4D), ruling out ERP differences due to saccades.

Compared with extinguished Lfs, BSS trials with seen faces evoked a later positive wave at 190–200 ms over right central and midline regions (Fig. 4D). The effect of condition (Rs, BSSfs extinguished, BSSfs perceived) was highly significant [F(2,21) = 7.23, P = 0.004]. Paired comparisons with Rs indicated that P190 occurred with seen [t(7) = 3.63, P = 0.008] but not extinguished faces [t(7) = 0.76, P = 0.47], whereas perception and extinction differed from each other [t(7) = 2.92, P = 0.02]. However, eye position tended to differ around 200 ms and may have contributed to the latter differences in ERP.

Discussion

This study provides combined spatial and temporal analysis of neural activity evoked by seen and unseen stimuli in neglect, using both event-related imaging and electrophysiological measures. Our findings have implications not only for theories of extinction in parietal injury and mechanisms of attention, but also for the processing of faces, and more generally, for the neural correlates of visual awareness.

Both fMRI and ERPs showed that contralesional inputs can still activate striate and extrastriate areas in the damaged hemisphere after parietal lesion, even without awareness. By comparing fMRI signals for shapes presented alone in the normal RVF and the same shapes presented with an extinguished face in the LVF (i.e., different stimuli but same percept), we found that unseen faces activated right visual cortex (V1) and inferior temporal areas, just lateral to fusiform regions with face-specific responses. This activation was weak compared with seen stimuli, but remarkably specific. Moreover, these regions exhibited a similar time course of activity when the face was extinguished or seen (Fig. 2). Similarly, ERPs showed that extinguished faces elicited early occipital responses, with no significant reduction of N1 relative to seen faces (but no reliable P1). N1 latencies were shorter than those reported in young normals, on both the intact and lesioned sides, possibly because of our patient's age or neurological status. Unseen faces also evoked a later negativity in right temporal sites, not evoked by shapes, with the same latency as the N170 known to be selective for faces (19, 25).

On the other hand, fMRI showed that awareness of physically identical stimuli in the LVF (as compared with extinction) was associated with activation of a distributed network including primary cortex (V1), cuneus, bilateral fusiform gyri, and the intact left parietal cortex. ERPs also were modulated by awareness, with nonsignificant increases of early occipital P1, and later anterior responses (≈200 ms at midline).

In agreement with our results, another event-related fMRI study of visual extinction (16) found preserved activation of striate cortex by unseen stimuli. Those authors also reported category-specific response to extinguished faces (as compared with pictures of houses) but only when examining a small predefined region of interest in the right fusiform gyrus and at low statistical threshold. Their patient missed contralesional stimuli on all bilateral trials, precluding a comparison with perceived stimuli. By contrast, we were able to demonstrate distinct patterns of activity associated with seen and unseen faces and found no evidence of unconscious activation in face-specific fusiform areas. Other positron-emission tomography or fMRI studies of tactile extinction yielded conflicting results, with either preserved§§ or decreased (27) activity of primary sensory cortex. However, their blocked design precluded assessment of single events with or without awareness. A single case study using ERPs (15) failed to demonstrate early visual responses (P1-N1) to extinguished stimuli. However, stimuli were small light-emitting diodes in far peripheral field, presumably evoking too weak activity in the visual system to allow reliable ERP signals without attention, and recordings were made at parietal, rather than occipital sites. In our patient, unseen faces elicited an early occipital N1 response and also a later face negativity in the temporal region.

Neural activity evoked by stimuli without awareness has been found in normal subjects (28) or in hemianopic patients with blindsight (29, 30). Blindsight has raised questions as to the role of area V1 in visual awareness (31, 32) because its destruction suppresses vision despite residual unconscious performance. We found that V1 was still activated by extinguished stimuli, without affording awareness (see also ref. 16). Yet, V1 was further activated when contralesional faces were seen, as compared with activity elicited by unseen stimuli. This finding may suggest some critical interaction with modulatory or reentrant signals from other brain areas (33). In our patient, fMRI analysis of effective connectivity revealed that increases in V1 and fusiform activity during awareness of faces were coupled with increases in a network of frontal and parietal areas that are implicated in spatial attention in normals (4, 12, 34). These results also converge with recent evidence that attentional modulation can operate both at early and late stages of vision (11, 35, 36).

Preserved cortical activation by unseen faces in our study and others (16) illuminates the neural basis of residual processing in neglect and extinction, implicating object segmentation (6, 7, 37) or semantic analysis (8) in occipital and temporal cortex. However, this result does not imply that activation in the ventral stream is fully intact (38). Unseen faces evoked a distinctive ERP negativity and fMRI activity in the inferior temporal gyrus, but only seen faces activated medial fusiform areas (Fig. 2). These areas may subserve different aspects of face processing (39, 40). Inferior temporal cortex may encode face structure and be automatically engaged (41), whereas fusiform cortex may extract specific face traits (18) and is modulated by attention (42) or explicit detection of faces (43, 44).

This anatomical dissociation has implications for the generators of face-specific ERPs that occurred for extinguished faces. In normals, faces evoke a temporal negativity and a midline positivity between 170 and 190 ms (19, 20). Our data suggest that these components may reflect distinct sources (45, 46). N170 potentials might index an early stage of face processing in temporal cortex (19, 46), whereas positive potentials might involve a distinct stage in fusiform and anterior regions (20, 21, 45). Consistent with this dissociation, N170 is not modulated by attention in normals (47).

It has been posited that visual awareness may depend on the ventral stream (10) and/or striate cortex (31), whereas dorsal parietal areas operate without awareness. However, our results and others (16, 30) show that striate and ventral activity is not sufficient to support awareness without some interaction with parietal, and perhaps frontal, areas. We found parietal activation in the intact hemisphere only when contralesional faces were seen (as opposed to extinguished), and a coupling of superior and inferior parietal regions with the fusiform gyrus specific to such events. We cannot entirely exclude a role of differential eye movements, but these parietal regions and cuneus have been implicated in distinct aspect of attention across a variety of tasks irrespective of eye movements (34, 48). Moreover, detection of a face in degraded stimuli is accompanied by long-distance coupling between parietal and occipitotemporal regions (43, 49). We suggest that visual awareness may relate to the integration of processing along both dorsal and ventral streams, binding “what” and “where” information about stimuli to afford selective attention and directed action (26). Damage to inferior parietal regions serving to link the dorsal and ventral streams might result in neglect and extinction, whereas residual processing might still occur in occipital and temporal areas without awareness.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to J. Armony for invaluable help in statistical parameter mapping analysis, as well as to T. Landis, P. Halligan, J. Driver, R. Dolan, N. Kanwisher, and S. Schwartz for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (P.V.), McDonnell-Pew Program in Cognitive Neuroscience (R.A.P. and D.S.), the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (D.S.), and the U.S. Public Health Service (R.D.R.).

Abbreviations

- BSS

bilateral simultaneous stimulation

- fMRI

functional MRI

- ERP

event-related potential

- RVF

right visual field

- LVF

left visual field

- Lf

left face

- Rf

right face

- Ls

left shape

- Rs

right shape

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Parts of these results were reported at the Annual Meeting of the Swiss Society for Behavioral Neurology in Bern, October 30, 1999, and at the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society in San Francisco, April 8–10, 2000.

Beversdorf, D. Q., Anderson, J. M., Auerbach, E. J., Briggs, R. W., Hughes, J. D., Crosson, B. & Heilman, K. M. (1999) Neurology 52, Suppl. 2., A232 (abstr.).

References

- 1.Heilman K M, Watson R T, Valenstein E. In: Neglect and Related Disorders. Heilman K M, Valenstein E, editors. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 1993. pp. 279–336. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rafal R D. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4:231–236. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driver J, Mattingley J B. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:17–22. doi: 10.1038/217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mesulam M M. Ann Neurol. 1981;4:309–325. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Posner M I, Petersen S. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:25–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward R, Goodrich S, Driver J. Visual Cognit. 1994;1:101–129. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vuilleumier P, Landis T. NeuroReport. 1998;9:2481–2484. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199808030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berti A, Rizzolatti G. J Cognit Neurosci. 1992;4:345–351. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1992.4.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driver J, Vuilleumier P. Cognition. 2001;79:39–88. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milner A D, Goodale M A. The Visual Brain in Action. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillyard S A, Teder-Sälerärvi W A, Münte T F. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:202–210. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corbetta M, Shulman G L. Philos Trans R Soc London B. 1998;353:1353–1362. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perani D, Vallar G, Paulesu E, Alberoni M, Fazio F. Neuropsychologia. 1993;31:2115–2125. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(93)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallar G, Sandroni P, Rusconi M L, Barbieri S. Neurology. 1991;41:1918–1922. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.12.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marzi C, Girelli M, Miniussi C, Smania N, Maravita A. J Cognit Neurosci. 2000;12:869–877. doi: 10.1162/089892900562471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rees G, Wojciulik E, Clarke K, Husain M, Frith C D, Driver J. Brain. 2000;123:1624–1633. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.8.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sergent J, Ohta S, Macdonald B. Brain. 1992;155:15–36. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun M M. J Neurosci. 1996;17:4302–4311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bentin S, Allison T, Puce A, Perez E, McCarthy G. J Cognit Neurosci. 1996;8:551–565. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1996.8.6.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeffreys D A. Visual Cognit. 1996;3:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allison T, Puce A, Spencer D, McCarthy G. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:415–430. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.5.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vuilleumier P, Rafal R. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:783–784. doi: 10.1038/12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friston K J, Holmes A P, Worsley K J, Poline J B, Frith C D, Frackowiak R S. Hum Brain Mapp. 1995;2:189–210. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1996)4:2<140::AID-HBM5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friston K. Hum Brain Mapp. 1994;2:56–78. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eimer M. Cognit Neuropsychol. 2000;17:103–116. doi: 10.1080/026432900380517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robertson L, Treisman A, Friedman-Hill S, Grabowecky M. J Cognit Neurosci. 1997;9:295–317. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Remy P, Zilbovicius M, Degos J D, Bachoud-Levy A C, Rancurel G, Cesaro P, Samson Y. Neurology. 1999;52:571–577. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobel N, Prabhakaran V, Hartley C A, Desmond J E, Glover G H, Sullivan E V, Gabrieli J D E. Brain. 1999;122:209–217. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahraie A, Weiskrantz L, Barbur J L, Simmons A, Williams S C R, Brammer M J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9406–9411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baseler H A, Morland A B, Wandell B A. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2619–1627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02619.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiskrantz L. Blindsight: A Case Study and Implications. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crick F, Koch C. Nature (London) 1995;375:121–123. doi: 10.1038/375121a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corthout E, Uttl B, Ziemann U, Cowey A, Hallett M. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(98)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corbetta M, Kincade J M, Ollinger J M, McAvoy M P, Shulman G L. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:292–297. doi: 10.1038/73009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghandi S P, Heeger D J, Boyton G M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3314–3319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Somers D C, Dale A M, Seiffert A E, Tootell R B H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1663–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Driver J, Baylis G C, Rafal R D. Nature (London) 1993;360:73–75. doi: 10.1038/360073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farah M J, Monheit M A, Brunn J L, Wallace M A. Neuropsychologia. 1991;29:949–958. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(91)90059-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.George N, Dolan R J, Fink G R, Baylis G C, Russell C, Driver J. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:574–580. doi: 10.1038/9230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haxby J V, Hoffman E A, Gobbini M I. Trends Cognit Neurosci. 2000;4:223–232. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grill-Spector K, Kushnir T, Edeleman S, Avidan G, Itchak Y, Malach R. Neuron. 1999;24:187–203. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80832-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wojciulik E, Kanwisher N, Driver J. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1574–1578. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.3.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dolan R J, Fink G R, Rolls E, Booth M, Holmes A, Frackowiak R S J, Friston K J. Nature (London) 1997;389:596–599. doi: 10.1038/39309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tong F, Nakayama K, Vaughan J T, Kanwisher N. Neuron. 1998;21:753–759. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.George N, Evans J, Fiori N, Davidoff J, Renault B. Cognit Brain Res. 1996;4:65–76. doi: 10.1016/0926-6410(95)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bentin S, Deouell L Y. Cognit Neuropsychol. 2000;17:35–54. doi: 10.1080/026432900380472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Séverac Cauquil A, Edmonds G E, Taylor M J. NeuroReport. 2000;11:2167–2171. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200007140-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wojciulik E, Kanwisher N. Neuron. 1999;23:747–764. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodriguez E, George N, Lachaux J-P, Martinerie J, Renault B, Varela F J. Nature (London) 1999;397:430–433. doi: 10.1038/17120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]