Abstract

The history of proline sulfonamides for use in catalyzing highly enantioselective and diastereoselective C-C bond forming reactions is described. Highlighted is the development of N-(p-dodecylphenylsulfonyl)-2-pyrrolidinecarboxamide (“Hua Cat”) and N-(carboxy-p-dodecylphenylsulfonyl)-2-pyrrolidinecarboxamide (“Hua Cat-II”) by Yang and Carter. Specific reactions covered include the aldol reaction, Mannich reaction, formal aza-Diels-Alder reaction, tandem Michael/Mannich reaction and Yamada-Otani reaction. The ability of proline aryl sulfonamides to construct all-carbon quaternary stereocenters in high enantioselectivity and diastereoselectivity is a notable feature of the reported work. The practicality of this chemistry for large scale and industrial applications is also included. Finally, a discussion of the future directions of proline sulfonamide organocatalysis is provided.

Keywords: asymmetric catalysis, amino acids, enantioselectivity, sulfonamides, solvent effects, aldol reaction, multicomponent reaction, Michael addition, phase-transfer catalysis

1. Introduction

A great deal of interest has been focused in the past decade towards the use of enantiomerically enriched organic molecules as catalysts for facilitating enantioselective transformations – particularly carbon-carbon bond forming reactions. This interest was largely catalyzed by the seminal work of Listi and MacMillanii in 2000. Numerous reviews have been written on the subject.iii Interestingly, while the name “Organocatalysis” was coined by MacMillan in 2000,ii the general concept has been around for far longer. As early as 1954, Prelog reported the use of cinchona alkaloids for an asymmetric cyano-hydrin reaction.iv A flurry of activity began in field starting in the late 1960’s. Yamada and co-workers exploited the utility of stoichiometric proline-derived enamines for inducing asymmetry in a range of transformations.v Hajos and Parrish’s seminal work focused on a proline-catalyzed process for an intramolecular aldol reaction to construct bicyclic ring systems.vi Wiechert, Eder and Sauer also reported the use of chiral amino acids as catalysts in a related process.vii These important early discoveries laid the groundwork for the 21st century renaissance that this field has enjoyed – leading to the wealth of exciting chemistry being developed today. The utility of proline and proline derivatives for facilitating organocatalyzed reactions has proven particularly significant.

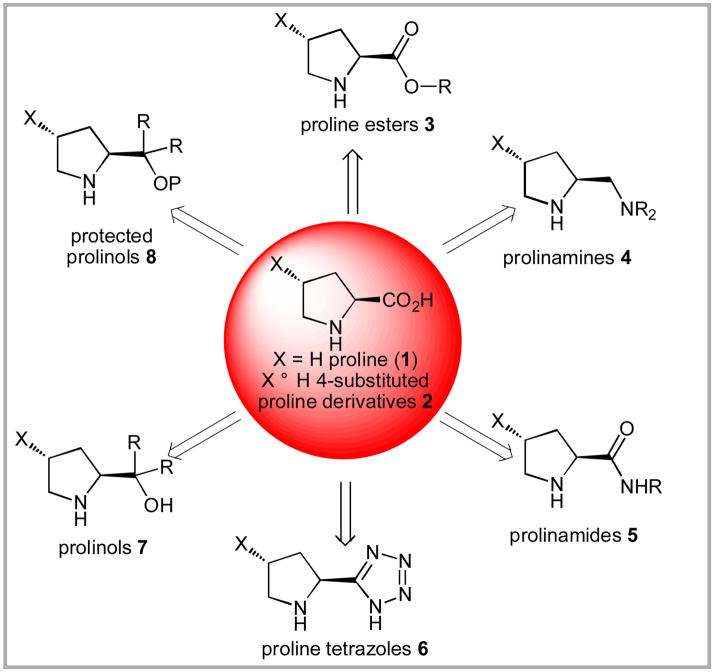

The proline-based organocatalysts can be broken down into seven general categories: proline and 4-trans-hydroxyproline derivatives 2, proline esters 3, prolinamines 4, prolinamides 5, proline tetrazoles 6, prolinols 7 and protected prolinols 8 (Scheme 1). For the purposes of this account, prolinamides can be broken down further into three sub-categories: simple amides 9 which do not contain significant additional functionality or stereochemistry, polystereogenic amides 10 and sulfonamides 11 (Figure 1).

Scheme 1.

Classes for Proline Derivatives.

Figure 1.

Subclasses of Prolinamides.

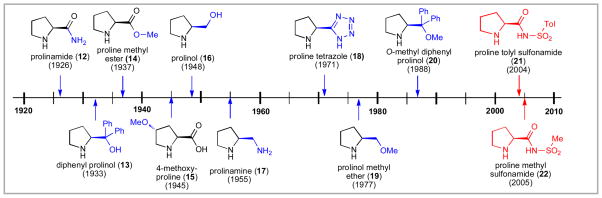

Interestingly, proline sulfonamides represent one of the most recent additions to this large family of compounds (Figure 2). Since the discovery of 4-hydroxyproline by Fischer in 1902, viii a wealth of proline derivatives have been synthesized. Based on SciFinder Scholar searches, prolinamide (12),ix diphenyl prolinol (13)x and proline methyl ester (14)ii,xi were first reported prior to 1940. 4-Methoxyproline (15),viiib prolinol (16)xii and prolinamine (17)xiii were produced shortly thereafter. Proline tetrazole (18) was first synthesized in 1971 by Grzonka and coworkers.xiv Prolinol methyl ether (19)xv,xiic and its diphenyl derivative 20xvi were first reported in 1977 and 1988 respectively. Ether 20 was the important precursor for more recent diarylsilyloxy organocatalysts developed by Jørgensen and others.xvii In contrast, the first proline sulfonamide was not reported until a tRNA synthetase inhibitor was studied by Easton and co-workers in 2003.xviii Prior reports of proline sulfonamides were limited to three patent applications.xix Interestingly, sulfonamides have been viewed as comparable to carboxylic acids in acidity.xx,xxi,xxii Herein, we provide a detailed account of how the field of proline sulfonamide organocatalysis developed and in what directions it may be headed. Included within this Account is our own discoveries of N-(p-dodecylphenylsulfonyl)-2-pyrrolidinecarboxamide (“Hua Cat”)xxiii and N-(carboxy-p-dodecylphenylsulfonyl)-2-pyrrolidinecarboxamide (“Hua Cat-II”).

Figure 2.

Timeline of Proline Derivatives.

2. Proline Sulfonamides

2.1 Synthesis of First Proline Sulfonamides

Berkessel and co-workers reported the synthesis of the first proline aryl sulfonamides in 2004 (Scheme 2).xxiv They reported the potential organocatalytic activity of three proline aryl sulfonamide catalysts (catalysts 21, 25, and 26) with the reaction of acetone and p-nitrobenzaldehyde in a series of solvents and catalyst loadings.

Scheme 2.

Berkessel’s Early Sulfonamide Aldol Examples (2004).

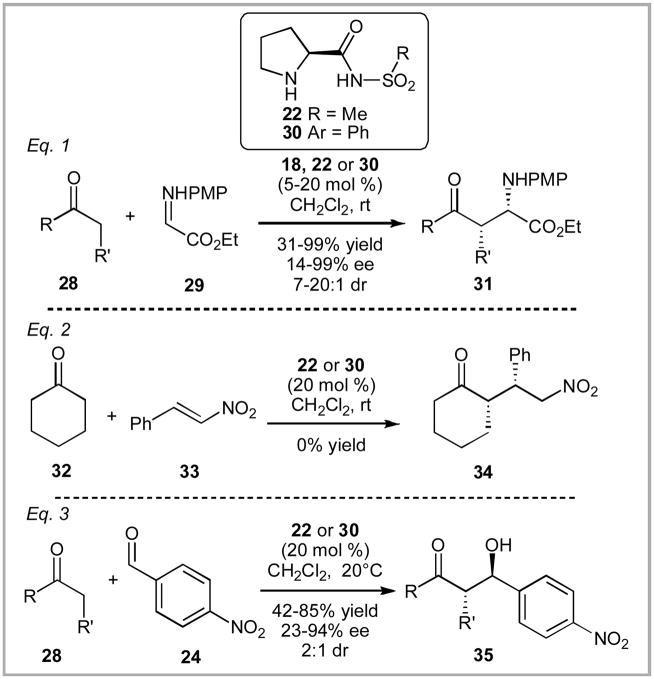

In the following year, Ley and co-workers reported the synthesis of the parent members of the sulfonamide family - proline methyl sulfonamide 22 and proline phenyl sulfonamide 30 (Scheme 3).xx These catalysts proved modestly effective at facilitating both aldol reactions and Mannich reactions – although the scope of substrates screened in this article was fairly narrow. In the same manuscript, Ley also reported their work with tetrazole 18 which Ley has continued to focus on after in subsequent manuscripts.xxv In contrast, this article represents the sole published work from the Ley group on sulfonamide organocatalysis. Ley commented that the tetrazole 18 provided “significant advantages” over sulfonamide catalysts 22 or 30 through shorter reaction times and lower catalyst loading on otherwise identical transformations. Tetrazole 18 also provided unique reactivity that the sulfonamide catalysts were incapable of generating such as the Michael addition of cyclohexanone to α,β-unsaturated nitro compounds. Ley did note that sulfonamides 22 and 30 performed well in aldol reactions, as represented in Equation 3 (Scheme 3). Dichloromethane proved to be the optimum solvent in these transformations. It should be noted that the enantioselectivity in most cases was modest and the diastereoselectivity was general low. Finally, they observed that sulfonamides 22 and 30 had improved solubility properties to tetrazole 18 and proline.

Scheme 3.

Ley’s Early Sulfonamide Examples (2005).

In 2005, Adolfsson and Córdova reported the use of sulfonamides for the α-oxidation of ketones and enones using nitrosobenzene in up to 80% yield with excellent enantioselectivity (Scheme 4).xxvi Ley’s methyl sulfonamide catalyst 22 proved to be the most effective out of a range of catalysts screened in the process. Córdova also screened catalyst 22 for use in aza-Diels-Alder reactions, but found proline to be more effective.xxvii

Scheme 4.

Adolfsson and Córdova’s α-Oxidation of Ketones and Enones (2005).

2.2 Early Proline Sulfonamide Organocatalysis

Several laboratories reported examples of using proline sulfonamides as organocatalysts in enantioselective aldol reactions. Zhao and Wang developed dendritic proline sulfonamide catalysts for use in aqueous aldol reactions.xxviii Gouverneur and co-workers utilized phenyl sulfonamide catalyst 30 in an aldol reaction involving an α-OMOM protected ketone and benzaldehydes.xxix Liu and co-workers showcased the ability of the same sulfonamide catalyst 30 to facilitate aldol reactions with trifluoromethyl ketone.xxx Frongia explored the synthesis of phenylthio- and phenoxyaldol adducts using catalyst 30.xxxi

Kokotos and co-workers reported the first examples of 4-hydroxy proline derived sulfonamides (Scheme 5).xxxii The authors commented that the benzyl ether protecting group on the 4-position imparted improved solubility properties as compared to proline itself.xxxiii,xxxiv The scope of the reaction was limited to a single substrate and a polar solvent (DMF) was still utilized in the reaction. Interestingly, use of the standard sulfonamides 22 and 30 gave similar results (62–81% yield, 76–85% ee). Fu and co-workers later reported the use of 4-silyloxy proline sulfonamides in a related transformation.xxxv Unfortunately, 4-trans-hydroxyproline is only commercially available in the (2S,4R) configuration shown below and is approximately ten times more expensive than proline itself.

Scheme 5.

Kokotos’s 4-Benzyoxyproline Sulfonamide-Catalyzed Aldol Reactions.

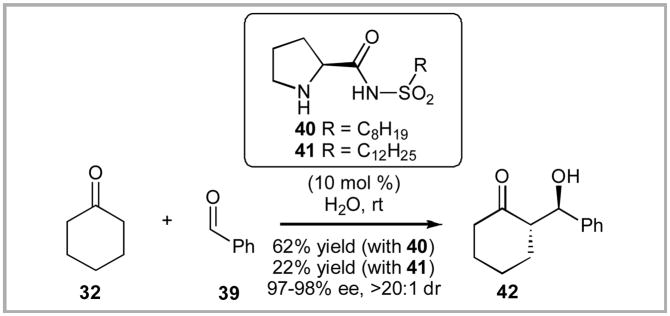

We were particularly intrigued by Hayashi and coworkers’ publication in late 2007 in which they detailed their elegant work utilizing 4-silyloxy proline as a viable organocatalyst.xxi Within this full paper, a brief investigation into the use of long alkyl chains on an alkyl proline sulfonamide scaffold was included (Scheme 6). They screened two alkyl sulfonamides 40 and 41 and explored a single aldol reaction between benzaldehyde and cyclohexanone in aqueous media. Interestingly, a strong relationship between the length of the alkyl chain and the chemical yield of the aldol reaction was observed.

Scheme 6.

Hayashi’s Alkyl Sulfonamide Catalyzed Aldol Reaction.

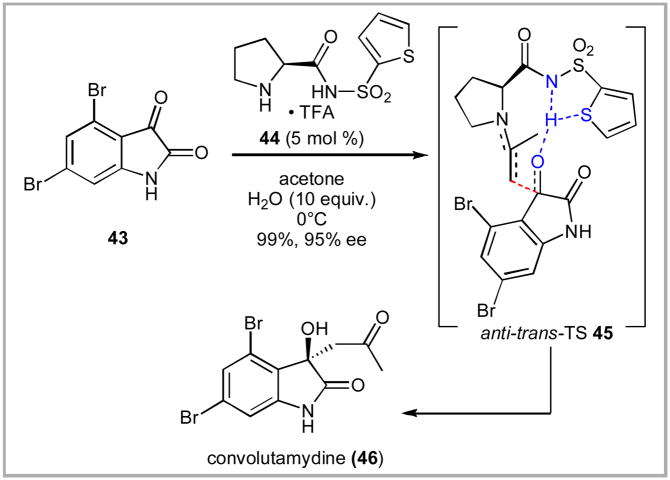

Nakamura, Toru and co-workers illustrated a nice example of proline sulfonamides’ organocatalytic potential in their convolutamydine synthesis. A thiophene-containing proline sulfonamide was used as the key organocatalyst for facilitating an aldol reaction between acetone and dibromoisatin 43 (Scheme 7).xxxvi They hypothesized a favorable hydrogen-bonding interaction between the thiophene and the sulfonamide as shown in transition state 45 to explain the improved stereoselectivity. Rasmini and coworkers demonstrated another interesting application of the proline sulfonamide through their use as polymeric aldolase mimics.xxxvii

Scheme 7.

Nakamura and Toru’s Thiophene-Derived Proline Sulfonamide Catalyst.

With the exception of Ley’s early Mannich examples on five different substratesxx,xxxiiid and Cordova’s oxygenation work,xxvi the majority of the chemistry reported using proline sulfonamide organocatalysis focused on the aldol reaction. In addition, there were several examples of transformations in which other catalysts such as the proline tetrazole 18xx,xxxviii or proline itselfxxvii,xxxix,xl,xli prove superior. It became clear to us that while preliminary work demonstrated the viability of proline sulfonamides as organcatalysts, the unique reactivity of these catalysts had not been fully realized. Furthermore, no chemistry had been developed with proline sulfonamides that alternative catalysts could not also facilitate effectively.

3. Hua Cat

3.1 Discovery of Hua Cat

The practical ease of these organocatalytic transformations (usually not requiring inert atmosphere or anhydrous conditions) coupled with the inexpensive source of chirality and lack of toxic reagents have attracted literally hundreds of research groups to the burgeoning research area. Consequently, the highly competitive nature of the field has led to multiple cases of independently and concurrently discoveries of the same (or closely related) transformation. Furthermore, one possible viewpoint of the field could be that its pioneers have already made most of the key discoveries with organocatalyst-based scaffolds.

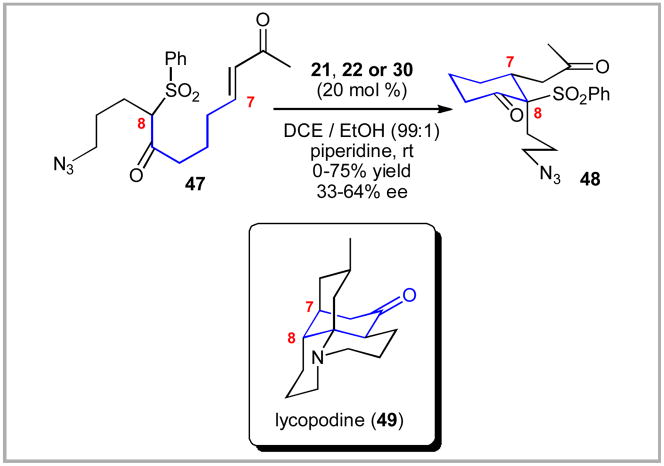

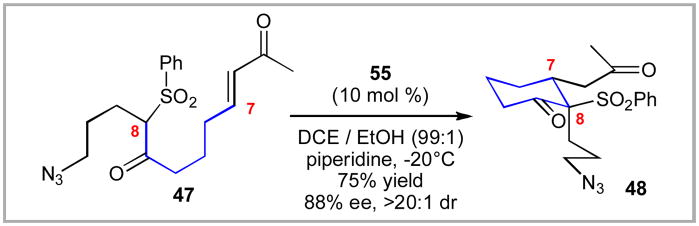

Our research group entered the field of organocatalysis with great trepidation to address a stereochemical challenge in our synthetic efforts towards the lycopodium alkaloids.xlii In 2006, we were exploring an intramolecular Michael addition reaction of a ketosulfone onto a methyl enone moiety in compound 47. This transformation was central to establishing the C7,8 stereochemical array of lycopodine. While we had initially expected that the existing organocatalysis literature would allow us to address this challenge in short order, we quickly realized that none of the known catalyst systems were effective at accomplishing this transformation. The challenge with this reaction was that we required non-polar solvents and low temperatures to achieve reasonable levels of enantiomeric excess. Unfortunately, most catalysts that proved effective at room temperature were simply not soluble in non-polar solvents at lower temperatures. In fact, the catalysts would often crystallize out of the reaction mixture upon cooling to below 0°C. To make matters worse, an unwanted background reaction became more prevalent at lower temperatures leading to the formation of a more complicated mixture. These two attributes led to the consistent observation that reduced temperatures led to worse levels of enantioselectivity!

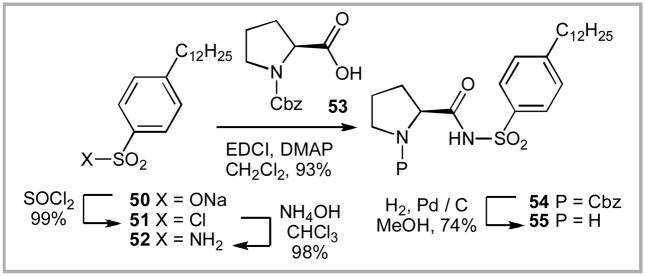

One of the catalyst systems that we had initially screened was the proline sulfonamides –– specifically catalysts 21, 22 and 30. We had not expected these catalysts to prove useful in this transformation as Ley reported little success using them in Michael addition reactions.xxa Interestingly, these sulfonamides proved to be some of the most active catalysts we screened for this transformation. The similar reactivity between the phenyl and the p-tolyl sulfonamides 30 and 21 respectively presented us with an interesting question: if the para-substitution on the aromatic ring was not detrimental, could we attach a non-polar sidearm to further improve solubility? A scan of the literature revealed that either para-dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid chloride 51 was commercially available from Wako Chemicals as was the sodium sulfonate salt 50 from a vast array of manufactures. The sulfonate salt 50 can be readily converted to the sulfonyl chloride 51 by treatment with 3 equiv. of oxalyl chloride at room temperature for 13 h in quantitative yield. This scaffold is widely used to make detergents and is available inexpensively on metric ton scale. While the dodecyl chain on the aromatic ring existed as an isomeric mixture (e.g. 1-dodecyl, 2-dodecyl, etc.), we did not feel this would adversely impact the reaction. In fact, the mixture of dodecyl isomers might improve the solubility of any proline-derived sulfonamide catalyst. We quickly ascertained that the corresponding sulfonamide 52 could be prepared from sulfonyl chloride 51 by treatment with ammonium hydroxide in high yield. Subsequent coupling with Cbz-protected proline 53 followed by hydrogenation gave the target dodecylphenyl substituted sulfonamide 55.xliib,xliii This catalyst has been commercialized and will be available soon through Sigma-Aldrich and Synthetech, Inc.xxiii

3.2 Intramolecular Michael Additions

With the catalyst 55 in hand, we investigated its performance in the intramolecular Michael addition. While this work was only published recently,xliib it was the origin of our entry into the field of organocatalysis. To our delight, the catalyst 55 performed beautifully – generating the key cyclohexanone in high levels of enantioselectivity, diastereoselectivity and chemical yield. Due to the high solubility of 55, we were able to successfully lower the reaction temperature and catalyst loading all the while increasing the reaction concentration. The optimized conditions employed 10 mol % of catalyst 55. Ironically, this catalyst system, while useful, did not matriculate into the total synthesis of lycopodine,xlii but the foundation for the sulfonamide-based organocatalysis had been established.

Given the success at this individual transformation, we quickly screened to see if these reaction conditions could function more broadly for a range of intramolecular Michael additions.xliib We observed good levels of diastereoselectivity, enantioselectivity and chemical yields for these transformations. Both 5- and 6-membered cycloalkanones 57 (n = 1, 2) were accessible using this catalyst system.

3.3 Aldol Reactions

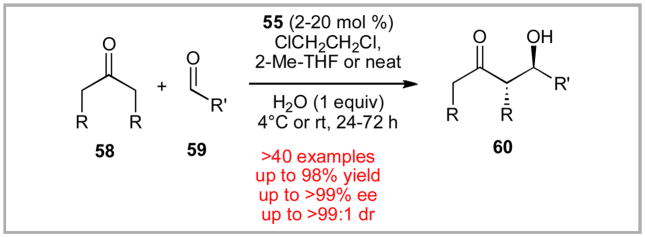

The success that we observed with the intramolecular Michael addition prompted us to investigate if catalyst 55 might prove more generally useful. Enantioselective aldol reactions have been often probed as a testing ground for new catalyst systems. While early examples of successful proline sulfonamide-based organocatalysis had been demonstrated by Berkessel, Ley and others, the scope of substrates explored was quite modest. Most examples had focused on acetone or cyclohexanone with p-nitrobenzaldehyde. Additionally, the level of diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity varied from low (e.g. 2:1 dr) to encouraging. Finally, the solvent systems employed had continued to focus on more polar media – likely due to the modest solubility of the previous catalyst systems in non-polar solvents such as dichloromethane. For example, the solubility of 1, 21, 22, and 30 in dichloromethane is all less than 5 mg/mL. In contrast, catalyst 55 displays excellent solubility in dichloromethane (300 mg/mL).xliiib We expected that improved levels of stereoselectivity might be accessible if these transformations were performed in less polar solvents.

Based on our successes in the intramolecular Michael additions, we felt non-polar solvents such as dichloroethane or dichloromethane would prove highly effective in these transformations. Our expectations were realized with excellent levels of diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity as well as chemical yield in the aldol reaction on a wide range of substrates.xliii While dichloroethane was the primary solvent reported in our original 2008 communication,xliiia we also have demonstrated that more industrially friendly solvents such as 2-methyl-tetrahydrofuran or neat reaction media are also effective in these transformation.xliiib The use of neat reaction conditions allowed us to dramatically drop the catalyst loading down to just 2 mol %. We even showed the practicality of this chemistry by conducting a 1 mole scale reaction in a single 500 mL round bottom flask. Based on this excellent reactivity, the fellow researchers in the group nicknamed the catalyst 55 “Hua Cat” (pronounce “Wha Cat”) after Dr. Hua Yang.

We also thought it was important to demonstrate whether our catalyst system was uniquely effective under these reaction conditions or if the yield and stereoselectivity was a general phenomenon for this transformation on the specified reaction conditions. Using our optimized conditions, we screened against the gamut of alternate sulfonamides 21–22 and 30 as well as proline (1) and its corresponding tetrazole 18. In each case, Hua Cat 55 gave superior results as compared to the other catalysts.xliii While all sulfonamides appeared to give improved levels of diastereoselectivity under the reaction conditions, the increased yields are likely due to the high solubility of 55.

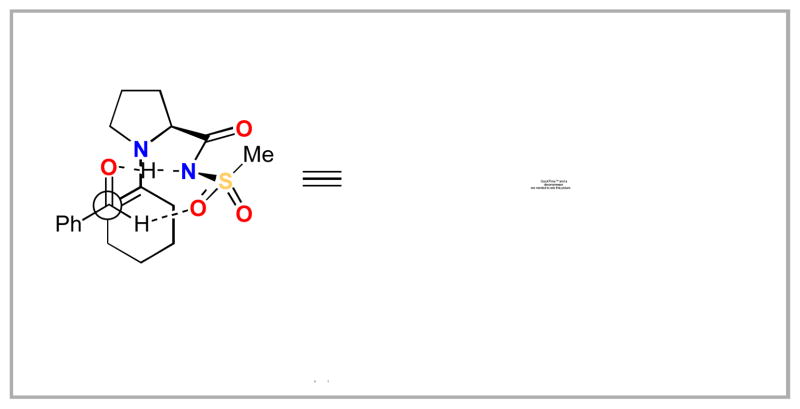

In 2009, Oregon State University hired a new computational organic chemist as a faculty member - Dr. “Paul” Ha-Yeon Cheong from Ken Houk’s group at UCLA. Through our collaboration with Professor Cheong’s research group, we have worked to garner a better understanding of this and related transformations. Consequently, we have recently developed an explanation for the improved level of diastereoselectivity observed with the proline sulfonamides (Figure 4).xliiib A non-classical hydrogen bond between the aldehyde C-H and the sulfonamide S-O appears to be keyto the increased diastereoselectivity.

Figure 4.

Preferred Anti-Re Transition State Based on Computational Model of Aldol Reaction with Proline Sulfonamides.

3.4 Mannich Reactions

As the Ley group had demonstrated early reactivity for proline sulfonamides in Mannich reactions,xx extension of this catalyst system to a thorough probe of this transformation seemed to be the logical next step (Scheme 13). Once again, catalyst 55 showed good substrate scope and provided reasonable levels of enantioselectivity and diastereoselectivity.xliv A total of sixteen examples were demonstrated with this transformation many of which provided access to – α or β-amino acids. The stereoselectivities and chemical yields of these transformations were generally good to excellent. Industrially friendly solvents such as 2-methyl tetrahydrofuran or neat reaction conditions could be employed. A 100 mmol example of a Hua Cat-catalyzed Mannich reaction was also conducted to showcase the potential scalability of this process.

Scheme 13.

Mannich Reactions Catalyzed by Hua Cat.

3.5 Aza Diels-Alder Reactions

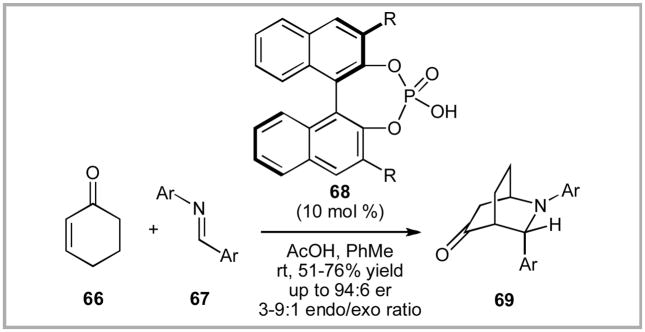

With good successes in both the aldol and Mannich reactions, we began to look for chemistry that Hua Cat (55) could possibly address that has not proven particularly effective with other catalysts systems. One structural class that had caught our attention was the azabicyclo-[2.2.2]-octanes (or isoquinuclidines). These compounds have generated considerable synthetic attention due to their presence in numerous alkaloid natural products,xlv,xlvi including the pharmaceutically relevant iboga alkaloids.xlvii Prior asymmetric work in the field had primarily focused on using enantioenriched BINOL-derived, phosphoric Brønsted acids with modestly endo-selective products (typically 3–4:1 endo:exo selectivity) and reasonable enantioselectivities (typically 76–88% ee).xlviii,xlix,l,li Pioneering work in the field by Rueping and Azap is shown in Scheme 14.xlviiia

Scheme 14.

Rueping’s Bronsted Acid-Catalyzed Formal Aza Diels Reaction.

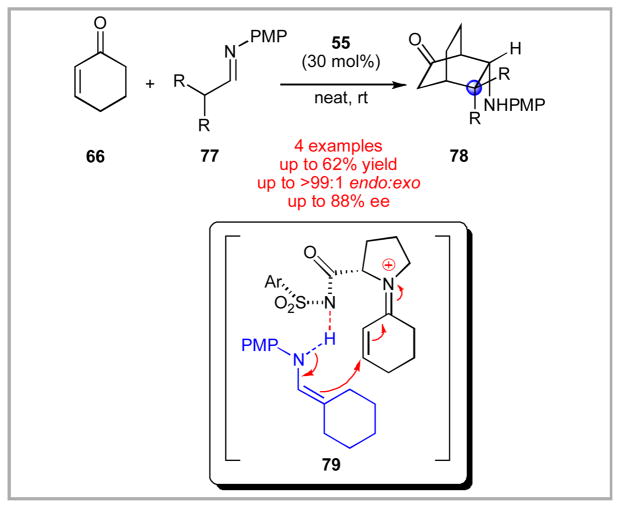

Cordova and co-workers disclosed the only organocatalyzed examples with this reaction class in 2005 (Scheme 15).xxvii Interestingly, they found in their reaction screening that proline (1) or tetrazole 18 worked better than the corresponding proline methyl sulfonamide 22. The manuscript principally focused on variation of the enone motif (6 or 7-membered rings, γ,γ-dimethyl substituted cyclohexanones). While their reactions proceeded well under these parameters, the chemistry was limited to formaldehyde-derived imines. They reported a single exception using the highly activated α-imino glyoxylate 29, which worked in only modest yield (25%), but with high exo selectivity. We hoped that our proline sulfonamide 55 might be able to expand the reaction scope - particularly on the imine substrate.

Scheme 15.

Cordova’s Proline Catalyzed Formal Aza-Diels Alder Reaction.

We were pleased to see that again Hua Cat (55) was able to deliver the required improvements to this transformation (Scheme 16).lii Sixteen examples of a wide array of aromatic imines can be utilized. In side-by-side comparisons, our sulfonamide 55 provided higher levels of chemical yield and enantioselectivity when compared to proline (1). These reactions are performed in the absence of solvent – which demonstrates the scalability and practicality of this chemistry for industrial processes. Finally, a complete reversal in the endo:exo selectivity is observed as compared to the chiral phosphoric acids – catalyst 55 favored exclusively the exo product. The reason for this reversal in selectivity is presently unknown.

Scheme 16.

Aza Diels-Alder Reaction Catalyzed by Hua Cat.

3.6 Quaternary Center Formation

During our exploration of the aza-Diels-Alder chemistry, we attempted to expand our imine substrate scope to include aliphatic imines. These substrates are particularly challenging due to their inherent ability to undergo imine/enamine tautomerization. Consequently, prior work in the field had largely avoided such substrates. Interestingly, use of catalyst 55 on these aliphatic imine structures revealed a divergent reaction pathway (Scheme 17).lii For example, treatment of alkyl imines 77 under the standard conditions did not result in the formation of the corresponding azabicyclo-[2.2.2]-octane product. Instead, the all-carbon bicyclo-[2.2.2]-octane variant 78 was produced.liii This product likely arises through a slow tautomerization of the imine structure to an enamine, which undergoes conjugate addition to iminium-activated cyclohexenone. We demonstrated that a variety of symmetrical dialkyl imines 77 were tolerated in this transformation. Monoalkyl imines and unsymmetrical alkyl imines generated inferior chemical yields using these conditions. While we were unsure at the time as to an exact mechanistic picture for this transformation, reviewers of this manuscript pressed for inclusion of a possible explanation. Consequently, we included in the manuscript a possible mechanistic cartoon where we involve a long range, hydrogen-bonding interaction between the sulfonamide nitrogen and the enamine N-H derived from tautomerization of imine 77.

Scheme 17.

Discovery of Quaternary Center Forming Reaction Cascade.

3.7 Stereogenic, All-Carbon Quaternary Center Formation in Bicyclic Scaffolds

We were particularly excited by the discovery of the reaction to form bicycle 78, which constructed two separate C-C bonds including an all-carbon quaternary center. While we only demonstrated a small subset of examples in Scheme 17, we quickly realized the potential in this transformation. If we could harness the quaternary center-forming capability of this chemistry for establishing stereogenic, all-carbon quaternary centers, this technology could have significant scientific impact. While the chemical yield is less than optimal, we were pleased to demonstrate a preliminary example for this transformation as shown in Scheme 18.lii We consider the construction of stereogenic, all-carbon quaternary centers to be one of the true remaining challenges in asymmetric catalysis – particularly in cases where few (if any) electron-withdrawing groups are bonded directly to the circled carbon in 81.liv,lv Inspection of the product 81 shown in Scheme 18, illustrates that the potential is present for addressing many of these challenges.

Scheme 18.

Preliminary Example of the Formation of an All-Carbon Stereogenic Center.

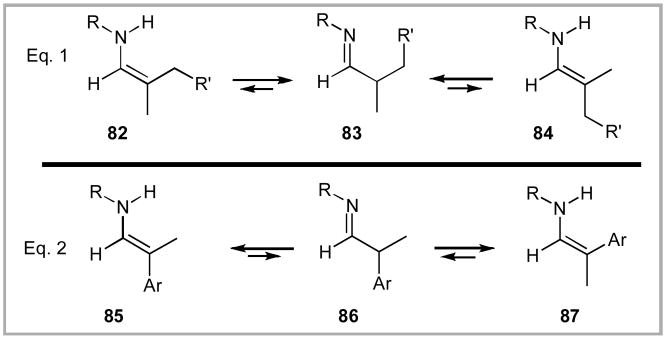

One major hurdle that we needed to address urgently in this chemistry was increasing the equilibrium ratio of the enamine(s) derived from the imine (Scheme 19). We saw two immediate solutions to this issue. First, the nature of the substituent R bonded directly to nitrogen should have an impact on imine/enamine ratio. For example, switching from the resonance electron-donating p-methoxyphenyl (PMP) moiety to a non-conjugated protecting group (e.g. Bn) should lower the pKa of the α-hydrogen and increase the ratio of enamine/imine tautomerization. Second, the use of benzylic imines (e.g. 86) should have a similar impact by providing additional stabilization to the enamines 85 and 87.

Scheme 19.

Equilibrium Between Enamines and Imine.

Recently, we have begun to address these challenges – by providing access to benzylic, all-carbon quaternary centers in high enantio- and diastereoselectivity (Scheme 20).lvi As we had hypothesized, key to this advance was the observation that 2-aryl substituted propanals 88 and benzyl amine (instead of p-methoxyphenylaniline) more readily generate the key enamine species. We demonstrated ten examples 89 – each containing four contiguous stereogenic centers in up to 98.3:1.7 er with excellent diastereoselectivity (>20:1 dr) and chemical yield (up to 76%). It is important to note that these multi-component reactions generate an equivalent of water through formation of the imine/enamine. Attempts to sequester this water through the use of molecular sieves led to inferior results. These scaffolds 89 should be applicable to a range of natural products such as kopsonoline (90).lvii

Scheme 20.

Enantioselective Synthesis of Stereogenic, All-Carbon Quaternary Center-Containing [2.2.2] Bicycles Catalyzed by Hua Cat.

3.8 Yamada-Otani Reaction

We next became interested in extending this chemistry to acyclic enone systems. Yamada and Otani laid the groundwork for this chemistry in the early days of organocatalysis (Scheme 21).v Despite their encouraging early success, the Yamada-Otani reaction laid essentially dormant for over four decades. We suspect that the reactivity in these systems has proven significantly more challenging to modulate on substrates not containing two-resonance electron-withdrawing substituents. Additionally, controlling diastereoselectivity in the key Michael addition step on acyclic enones possessing a β-non-hydrogen substituent adds an additional degree of complexity.

Scheme 21.

Yamada and Otani’s Pioneering Work.

After some additional optimization, we were able to extend our technology to the Yamada-Otani reaction with acyclic enone substrates (Scheme 22).lviii One important discovery was that a second-generation catalyst (Hua Cat-II) 98 provided improved levels of enantioselectivity. We attribute the difference in reactivity to the electron-withdrawing effect on the p-substituted ester on the aryl sulfonamide, which likely reduces the pKa of the sulfonamide N-H. We demonstrated twenty separate examples of this transformation with an average chemical yield of 60%. This methodology should be applicable to the synthesis of numerous steroidal natural products including viridin (100)lix and hinokione (101).lx During the peer review process of our work, Kotsuki and co-workers reported a greatly improved version of Yamada and Otani’s reaction.lxi Their elegant protocol involves a one-pot, two-step approach with a duel catalyst system of 30 mol % (1R,2R)-1,2-cyclohexanediamine and 30 mol % (1R,2R)-1,2-cyclohexanedicarboxylic acid and is effective on enone substrates which contain no substitution in the β-position. We view this work as a nice complement to our research as our sulfonamide catalysis shown in Scheme 22 works on enone substrates, which contain a β-non-hydrogen substituent on the enone.

Scheme 22.

Enantioselective Synthesis of Stereogenic, All-Carbon Quaternary Center-Containing Cyclohexenones Catalyzed by Hua Cat-II.

4 Future Directions

We have only begun to tap the potential of proline sulfonamides (Figure 4). New catalyst structures should lead to unique reactivity and new transformations. Our recent work on the Yamada-Otani reaction with our second-generation catalyst 98 is a prime illustration of the potential we see for catalyst modification.lviii We have also started to report additional examples of proline sulfonamide catalysts such as the deoxy catalyst 102 and the pyridyl catalyst 103.xliiib

Figure 4.

Future Generations of Proline Sulfonamide Organocatalysts.

Despite the wealth of research that has been conducted in the field of organocatalysis, it is our view that the synthetic community is only beginning to harness the full power of this technology. Proline sulfonamide organocatalysis may have emerged relatively late to the field, but the utility that our group and other laboratories have showcased bodes well for its future. The development of new reaction pathways (and catalysts) that push the boundaries of modern synthetic chemistry with increased structural complexity will likely continue for many years to come. Proline sulfonamide organocatalysis is well positioned to contribute to the future growth in this field.

5 Conclusion

A detailed account of the development of proline sulfonamide organocatalysis is provided. Pioneering work by Berkessel,xxiv Leyxx and Cordovaxxvi and leading examples from other research laboratories in the field are discussed. Our research program subsequently entered this field through the introduction of the N(p-dodecylphenylsulfonyl)-2-pyrrolidinecarboxamide (nicknamed “Hua Cat”). This catalyst 55 has proven useful at facilitating a range of organocatalytic transformations. Recent introduction of our second generation catalyst, N-(carboxy-p-dodecylphenylsulfonyl)-2-pyrrolidinecarboxamide (nicknamed “Hua Cat-II”), has helped to further advance the field of proline sulfonamide organocatalysis to include the construction of all-carbon quaternary centers in a high enantioselective and diastereoselective fashion.

Scheme 8.

Intramolecular Michael Addition for Lycopodine Core.

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of Hua Cat.

Scheme 10.

Application of Hua Cat to Lycopodine Core.

Scheme 11.

Scope of Intramolecular Michael Addition with Hua Cat.

Scheme 12.

Aldol Reactions Catalyzed by Hua Cat.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this research was provided by the Oregon State University (OSU) Venture Fund and the National Institutes of Health (GM63723). National Science Foundation (CHE-0722319) and the Murdock Charitable Trust (2005265) are acknowledged for their support of the NMR facility. RGC is a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Fellow (L-10568). Dr. Mike Standen and Synthetech, Inc. are acknowledged for their generous gifts of proline derivatives. We thank Dr. Lev N. Zakharov (OSU and University of Oregon) for X-ray crystallographic analysis as well as Professor Max Deinzer and Dr. Jeff Morre (OSU) for mass spectra data. Finally, we are grateful to Dr. Roger Hanselmann (Rib-X Pharmaceuticals), Professor James D. White (OSU), Dr. Mike Standen (Sythetech, Inc.), Professor Paul Ha-Yeon Cheong (OSU) and Subham Mahapatra (OSU) for their helpful discussions.

References

- i.List B, Lerner RA, Barbas CF., III J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:2395–2396. [Google Scholar]

- ii.Ahrendt KA, Borths CJ, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4243–4244. [Google Scholar]

- iii.(a) Chem Rev. 2007;(12):5413–5883. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dondoni A, Massi A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:4638–4660. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) MacMillan DWC. Nature. 2008;455:304–308. doi: 10.1038/nature07367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Merino P, Marques-Lopez E, Tejero T, Herrera RP. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:1219–1234. [Google Scholar]; (e) Xu L-W, Luo J, Lu Y. Chem Commun. 2009:1807–1821. doi: 10.1039/b821070e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Palomo C, Oiarbide M, Lopez R. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:632–653. doi: 10.1039/b708453f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Bella M, Gasperi T. Synthesis. 2009:1583–1614. [Google Scholar]; (h) Bertelsen S, Jorgensen KA. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:2178–2189. doi: 10.1039/b903816g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Alba AN, Companyo X, Viciano M, Rios R. Curr Org Chem. 2009;13:1431–1474. [Google Scholar]; (j) Liu X, Lin L, Feng X. Chem Commun. 2009:6145–6158. doi: 10.1039/b913411e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Raj M, Singh VK. Chem Commun. 2009:6687–6703. doi: 10.1039/b910861k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Merino P, Marques-Lopez E, Tejero T, Herrera RP. Synthesis. 2010:1–26. [Google Scholar]; (m) Grondal C, Jeanty M, Enders D. Nature Chem. 2010;2:167–178. doi: 10.1038/nchem.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Xu LW, Li L, Shi ZH. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;252:243–279. [Google Scholar]

- iv.Prelog V, Wihelm M. Helv Chim Acta. 1954;37:1634–1660. [Google Scholar]

- v.(a) Yamada SI, Otani G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969:4237–3240. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hiroi K, Achiwa K, Yamada SI. Chem Pharm Bull. 1972;20:246–257. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hiroi K, Yamada SI. Chem Pharm Bull. 1973;21:47–53. [Google Scholar]; (d) Otani G, Yamada SI. Chem Pharm Bull. 1973;21:2112–2118. [Google Scholar]

- vi.(a) Hajos ZG, Parrish DR. J Org Chem. 1974;39:1615–1621. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hajos ZG, Parrish DR. Organic Syntheses. VII. Wiley; New York: 1990. pp. 363–368. Collect. [Google Scholar]

- vii.Eder U, Sauer G, Wiechert R. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1971;10:496–497. [Google Scholar]

- viii.(a) Fischer E. Ber. 1902;35:2660. [Google Scholar]; (b) Neuberger A. J Chem Soc. 1945:429–432. [Google Scholar]

- ix.(a) Putchin N. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft [Abteilung] B: Abhandlungen. 1926;59B:1987–1998. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tang Z, Jiang F, Cui X, Gong LZ, Mi AQ, Jiang YZ, Wu YD. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5755–5760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307176101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- x.(a) Kaphhammer J, Matthes AZ. Physiol Chem. 1933;223:43–52. [Google Scholar]; (b) Winthrop SO, Humber LG. J Org Chem. 1961;26:2834–2836. [Google Scholar]

- xi.Kuhn R, Brydowna W. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft [Abteilung] B: Abhandlungen. 1937;70B:1333–1341. [Google Scholar]

- xii.(a) Karrer P, Portmann P, Suter M. Helv Chim Acta. 1948;31:1617–1623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Melchiorre P, Jorgensen KA. J Org Chem. 2003;68:4151–4157. doi: 10.1021/jo026837p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ramachary DB, Chowdari NS, Barbas CF., III Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:4233–4237. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xiii.(a) Schnell S, Karrer P. Helv Chim Acta. 1955;38:2036–2037. [Google Scholar]; (b) Steiner DD, Mase N, Barbas CF., III Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:3706–3710. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xiv.(a) Grzonka Z, Liberek B. Roczniki Chemii. 1971;45:967–80. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hartikka A, Arvidsson PI. Tetrahedron: Asymm. 2004;15:1831–1834. [Google Scholar]; (c) Momiyama N, Torii H, Saito S, Yamamoto H. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5374–5378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307785101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Cobb AJA, Shaw DM, Ley SV. Synlett. 2004:558–560. [Google Scholar]

- xv.(a) Seebach D, Kalinowski HO, Bastani B, Crass G, Daum H, Doerr H, DuPreez NP, Ehrig V, Langer W, Nussler C, Oei HA, Schmidt M. Helv Chim Acta. 1977;60:301–325. [Google Scholar]; (b) Feringa B, Wynberg H. Biorg Chem. 1978;7:397–408. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kolb M, Barth J. Angew Chem. 1980;92:753–754. [Google Scholar]; (d) Ahlbrecht H, Bonnet G, Enders D, Zimmerman G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:3175–3178. [Google Scholar]

- xvi.Enders D, Kipphardt H, Gerdes P, Brena-Valle LJ, Bhushan V. Bull Chim Soc Bel. 1988;97:691–704. [Google Scholar]

- xvii.Marigo M, Wabnitz TC, Fielenbach D, Jorgensen KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:794–797. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462101.Sunden H, Ibrahem I, Cordova A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;47:99–103.Hayashi Y, Gotoh H, Hayashi T, Shoji M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4212–4215. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500599.For a recent review, see: Larson GL. Speciality Chemicals Magazine. 2009;29(6):20–22.

- xviii.Crasto CF, Forrest AK, Karoli T, March DR, Mensah L, O’Hanlon PJ, Narin MR, Oldham MD, Yue W, Banwell MG, Easton CJ. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:2687–2694. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(03)00237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xix.(a) Walker ERH. EP 99709 A2 Eur Pat App. 1984; (b) Masui M, Hasegawa Y. WO 2002010101 A1 PCT Int App. 2002; (c) Blumberg LC, Brown MF, Hayward MM, Poss CS, Lundquist GD, Jr, Shavya A. WO 2003035627 PCT Int App. 2003

- xx.(a) Cobb AJA, Shaw DM, Longbottom DA, Gold JB, Ley SV. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:84–96. doi: 10.1039/b414742a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Masui M, Hasegawa Y. WO 2002010101 A1 PCT Int App. 2002

- xxi.Aratake S, Itoh T, Okano T, Nagae N, Sumiya T, Shoji M, Hayashi Y. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:10246–10256. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxii.Huang XY, Wang HJ, Shi J. J Phys Chem A. 2010;114:1068–1081. doi: 10.1021/jp909043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxiii.(a) Sigma-Aldrich Catalog Numbers: 733008 (S)-isomer, 733016 (R)-isomer. (b) Synthetech, Inc. Catalog Numbers: *24C806 (S)-isomer, *24C805 (R)-isomer.

- xxiv.Berkessel A, Koch B, Lex J. Adv Synth Cat. 2004;346:1141–1146. [Google Scholar]

- xxv.(a) Kumarn S, Shaw DM, Longbotton DA, Ley SV. Org Lett. 2005;7:4189–4191. doi: 10.1021/ol051577u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Knudsen KR, Mitchell CET, Ley SV. Chem Commun. 2006:66–68. doi: 10.1039/b514636d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mitchell CET, Brenner SE, Garcia-Fortanet J, Ley SV. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:2039–2049. doi: 10.1039/b601877g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Franckevicius V, Knudsen KR, Ladlow M, Longbottom DA, Ley SV. Synlett. 2006:889–892. [Google Scholar]; (e) Hansen HM, Longbottom DA, Ley SV. Chem Commun. 2006:4838–4840. doi: 10.1039/b612436b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Longbottom DA, Franckevicius V, Ley SV. Chimia. 2007;61:247–256. [Google Scholar]; (g) Wascholowski V, Hansen HM, Longbottom DA, Ley SV. Synthesis. 2008:1269–1275. [Google Scholar]; (h) Washolowski V, Knudsen KR, Mitchell CET, Ley SV. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:6155–6165. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Auereggi V, Franckevicius V, Kitching MO, Ley SV, Longbottom DA, Oelke AJ, Sedelmeier G. Org Synth. 2008;85:72–87. [Google Scholar]

- xxvi.Sunden H, Dahlin N, Ibrahem I, Adolfsson H, Cordova A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:3385–3389. [Google Scholar]

- xxvii.Sunden H, Ibrahem I, Eriksson L, Cordova A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4877–4880. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxviii.Wu Y, Zhang Y, Yu M, Zhao G, Wang S. Org Lett. 2006;8:4417–4420. doi: 10.1021/ol061418q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxix.Silva F, Sawicki M, Gouverneur V. Org Lett. 2006;8:5417–5419. doi: 10.1021/ol0624225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxx.Wang X-J, Zhao Y, Liu J-T. Org Lett. 2007;9:1343–1345. doi: 10.1021/ol070217z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxxi.Bernard AM, Frongia A, Piras PP, Secci F, Spiga M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:3037–3041. [Google Scholar]

- xxxii.Bellis E, Vasilatou K, Kokotos G. Synthesis. 2005:2407–2413. [Google Scholar]

- xxxiii.Meciarova and Toma have explored the use of ionic liquids as alternative solvent systems for proline sulfonamide catalyzed aldol reactions, Mannich reactions and Michael additions. Meciarova M, Toma S, Berkessel A, Koch B. Lett Org Chem. 2006;3:437–441.Meciarova M, Hubinska K, Toma S, Koch B, Berkessel A. Monash Chem. 2007;138:1181–1186.Meciarova M, Toma S, Sebesta R. Tetrahedron: Asymm. 2009;20:2403–2406.Veverkova E, Strasserova, Sebesta R, Toma S. Tetrahedron: Asymm. 2010;21:58–61.

- xxxiv.Zhang S-P, Fu X-K, Fu S-D, Pan J-F. Cat Commun. 2009;10:401–405. [Google Scholar]

- xxxv.Fu S-D, Fu X-K, Zhang S-P, Zou X-C, Wu X-J. Tetrahedron: Asymm. 2009;20:2390–2396. [Google Scholar]

- xxxvi.(a) Nakamura S, Hara N, Nakashima H, Kubo K, Shibata N, Toru T. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:8079–8081. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hara N, Nakamura S, Shibata N, Toru T. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:6790–6793. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxxvii.Carboni D, Flavin K, Servant A, Gouverneur V, Resmini M. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:7059–7065. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxxviii.Chowdari NS, Ahmad M, Albertshofer K, Tanaka F, Barbas CF., III Org Lett. 2006;8:2839–2842. doi: 10.1021/ol060980d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxxix.(a) Vogt H, Baumann T, Nieger M, Brase S. Eur J Org Chem. 2006;2006:5315–5338. [Google Scholar]; (b) Baumann T, Bachle M, Hartmann C, Brase S. Eur J Org Chem. 2008;2008:2207–2212. [Google Scholar]

- xl.Hajra S, Giri AK. J Org Chem. 2008;73:3935–3937. doi: 10.1021/jo8005733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xli.Samanta S, Perera S, Zhao C-G. J Org Chem. 2010;75:1101–1106. doi: 10.1021/jo9022099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xlii.(a) Yang H, Carter RG, Zakarov LN. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9238–9239. doi: 10.1021/ja803613w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang H, Carter RG. J Org Chem. 2010;75:4929–4938. doi: 10.1021/jo100916x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xliii.(a) Yang H, Carter RG. Org Lett. 2008;10:4649–4652. doi: 10.1021/ol801941j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang H, Mahapatra S, Cheong PY-H, Carter RGJ. Org Chem. doi: 10.1021/jo1015008. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xliv.Yang H, Carter RG. J Org Chem. 2009;74:2246–2249. doi: 10.1021/jo8027938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xlv.(a) Khan MOF, Levi MS, Clark CR, Ablordeppey SY, Law S-J, Wilson NH, Borne R. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry. 2008;34:753–787. (Bioactive Natural Products-Part N) [Google Scholar]; (b) Sundberg RG, Smith SQ. In: The Alkaloids. Cordell GA, editor. Vol. 59. Academic Press; 2002. p. 261. [Google Scholar]

- xlvi.Gagnon A, Danishefsky SJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:1581–1584. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020503)41:9<1581::aid-anie1581>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xlvii.(a) Sundberg RJ, Smith SQ. The Alkaloids. 2002;59:281–386. doi: 10.1016/s0099-9598(02)59009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Borschberg HJ. Curr Org Chem. 2005;9:1465–1491. [Google Scholar]

- xlviii.(a) Rueping M, Azap C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:7832–7835. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu H, Cun L-F, Mi A-Q, Jiang Y-Z, Gong L-Z. Org Lett. 2006;8:6023–6026. doi: 10.1021/ol062499t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xlix.(a) Shanthi G, Perumal PT. Syn Comm. 2005;35:1319–1327. [Google Scholar]; (b) Costantino U, Fringuelli F, Orru M, Nocchetti M, Piermatti O, Pizzo F. Eur J Org Chem. 2009;2009:1214–1220. [Google Scholar]

- l.Nakano H, Tsugawa N, Fujita R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;34:5677–5681. [Google Scholar]

- li.Graham PM, Delafuente DA, Liu W, Myers WH, Sabat M, Harman WD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10568–10572. doi: 10.1021/ja050143r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lii.Yang H, Carter RG. J Org Chem. 2009;74:5151–5156. doi: 10.1021/jo9009062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- liii.Sunden H, Rios R, Xu Y, Eriksson L, Cordova A. Adv Synth Cat. 2007;349:2549–2555. [Google Scholar]

- liv.(a) Bella M, Gasperi T. Synthesis. 2009:1583–1614. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cozzi PG, Hilgraf R, Zimmermann N. Eur J Org Chem. 2007:5969–5994. [Google Scholar]; (c) Denissova I, Barriault L. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:10105–10146. [Google Scholar]; (d) Christoffers J, Mann A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:4591–4597. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4591::aid-anie4591>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Corey EJ, Guzman-Perez A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:388–401. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980302)37:4<388::AID-ANIE388>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lv.(a) Zheng C, Wu Y, Wang X, Zhao G. Adv Synth Catal. 2008;350:2690–2694. [Google Scholar]; (b) Luo J, Xu LW, Hay RAS, Lu Y. Org Lett. 2009;11:437–440. doi: 10.1021/ol802486m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Enders D, Wang C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:7539–7542. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Murakata M, Jono T, Shoji T, Moriya A, Shirai Y. Tetrahedron: Asymm. 2008;19:2479–2483. [Google Scholar]; (e) Han B, Liu QP, Li R, Tian X, Xiong XF, Deng JG, Chen YC. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:8094–8097. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Baudequin C, Zamfir A, Tsogoeva SB. Chem Commun. 2008:4637–4639. doi: 10.1039/b804477e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Bernardi L, Fini F, Fochi M, Ricci A. Synlett. 2008:1857–1861. [Google Scholar]; (h) Li Y, Zhao ZA, He H, You SL. Adv Synth Catal. 2008;350:1885–1890. [Google Scholar]; (i) Tian X, Jiang K, Peng J, Du W, Chen Y-C. Org Lett. 2008;10:3583–3586. doi: 10.1021/ol801351j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Penon O, Carlone A, Mazzanti A, Locatelli M, Sambri L, Bartoli G, Melchiorre P. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:4788–4791. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Dietz FR, Groeger H. Synlett. 2008:663–666. [Google Scholar]; (l) Bogle KM, Hirst DJ, Dixon DJ. Org Lett. 2007;9:4901–4904. doi: 10.1021/ol702277v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Ogawa S, Shibata N, Inagaki J, Nakamura S, Toru T, Shiro M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:8666–8669. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Chen JR, Liu XP, Zhu XY, Li L, Qiao YF, Zhang JM, Xiao WJ. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:10437–10444. [Google Scholar]; (o) Xie H, Zu L, Li H, Wang J, Wang W. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10886–10894. doi: 10.1021/ja073262a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (p) Liu TY, Long J, Li BJ, Jiang L, Li R, Wu Y, Ding LS, Chen YC. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:2097–2099. doi: 10.1039/b605871j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (q) Knudsen KR, Jorgensen KA. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:1362–1364. doi: 10.1039/b500618j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (r) Mase N, Tanaka F, Barbas CF., III Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:2420–2423. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (r) Kinsman AC, Kerr MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14120–14125. doi: 10.1021/ja036191y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lvi.Yang H, Carter RG. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:4854–4859. [Google Scholar]

- lvii.Lim S-H, Sim K-M, Abdullah Z, Hiraku O, Hayashi M, Komiyama K, Kam T-S. Nat Prod. 2007;70:1380–1383. doi: 10.1021/np0701778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lviii.Yang H, Carter RG. Org Lett. 2010;12:3108–3111. doi: 10.1021/ol1011955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lix.(a) Brian PW, McGowan JC. Nature. 1945;156:144–145. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wipf P, Halter RJ. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:2053–2061. doi: 10.1039/b504418a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lx.(a) Chow YL, Erdtman H. Proc Chem Soc, London. 1960:174–175. [Google Scholar]; (b) Matsumoto T, Usui S, Kawashima H, Mitsuki M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1981;54:581–584. [Google Scholar]

- lxi.Inokoishi Y, Sasakura N, Nakano K, Ichikawa Y, Kotsuki H. Org Lett. 2010;12:1616–1619. doi: 10.1021/ol100350w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]