Abstract

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) inhibit anti-tumor immune responses and facilitate tumor growth. Precursors for these immune cell populations migrate to the tumor site in response to tumor secretion of chemokines, such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2), which was originally purified and identified from human gliomas. In syngeneic mouse GL261 glioma and human U87 glioma xenograft models, we evaluated the efficacy of systemic CCL2 blockade by monoclonal antibodies (mAb) targeting mouse and/or human CCL2. Intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of anti-mouse CCL2 mAb as monotherapy (2 mg/kg/dose, twice a week) significantly, albeit modestly, prolonged the survival of C57BL/6 mice bearing intracranial GL261 glioma (p=0.0033), which was concomitant with a decrease in TAMs and MDSCs in the tumor microenvironment. Similarly, survival was modestly prolonged in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice bearing intracranial human U87 glioma xenografts treated with both anti-human CCL2 mAb and anti-mouse CCL2 antibodies (2 mg/kg/dose for each, twice a week) compared to mice treated with control IgG (p=0.0159). Furthermore, i.p. administration of anti-mouse CCL2 antibody in combination with temozolomide (TMZ) significantly prolonged the survival of C57BL/6 mice bearing GL261 glioma with 8 of 10 treated mice surviving longer than 70 days, while only 3 of 10 mice treated with TMZ and isotype IgG survived longer than 70 days (p=0.0359). These observations provide support for development of mAb-based CCL2 blockade strategies in combination with the current standard TMZ-based chemotherapy for treatment of malignant gliomas.

Keywords: glioma, chemokine, CCL2, monoclonal antibody, chemotherapy, temozolomide

INTRODUCTION

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) is a member of the cytokine/chemokine superfamily and has been demonstrated to promote the accumulation of monocytes and macrophages to tumor sites [1,2], thereby promoting tumorigenesis and metastasis of several solid tumors, including breast cancer, multiple myeloma and prostate cancer [3–7]. In the tumor microenvironment, monocytes undergo aberrant differentiation into TAMs, which promote tumor growth and metastasis [8–10], and MDSCs, which inhibit anti-tumor immune responses [11–13].

Human MCP-l/CCL2 was originally purified from the tissue culture supernatant of a malignant glioma cell line as a factor that attracts human monocytes [14,15]. Indeed, human malignant gliomas are heavily infiltrated by macrophages/microglia [16]. Several reports indicate that glioblastomas express elevated CCL2, both at the mRNA and protein levels, as compared to normal brain [17–20] and that the glioma-derived CCL2 is capable of inducing monocyte migration in vitro [18]. Consistent with these observations, cerebrospinal fluid and cyst fluid from patients with glioblastoma also contain elevated levels of CCL2 [21]. Finally, it has been shown in an experimental tumor model that CCL2 expression by glioma is directly involved in accumulation of macrophages/microglia in glioma and promotes tumor aggressiveness [22]. Therefore, we hypothesized that effective blockade of CCL2 in vivo would inhibit accumulation of TAMs and MDSCs into intracranial gliomas, thereby inhibiting the growth of glioma.

Anti-mouse (C1142) and anti-human (CNTO 888) CCL2 mAbs were developed and have been shown to neutralize the function of cognate CCL2 molecules in vivo [7,23–25]. These reagents allowed us to evaluate our hypothesis in the following two well-established preclinical intracranial glioma models: 1) C57BL/6 mice bearing syngeneic GL261 glioma and 2) SCID mice bearing human U87 glioma xenografts. We also hypothesized that CCL2 blockade would augment the effect of other therapeutic strategies, such as chemotherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Female C57BL/6 mice (H-2b) and SCID mice (CBySmn.CB17-Prkdcscid/J) were obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) and JAX Mice (Bar Harbor, ME), respectively. All animals were handled in the Animal Facility at the University of Pittsburgh per an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol.

Cell culture

The mouse GL261 glioma cell line (H-2b) was kindly provided by Dr. Robert Prins (University of California Los Angeles, CA). The human U87 glioma cell line was purchased from ATCC (ATCC number HTB14). The GL261 and the U87 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 or DMEM, respectively, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 10 μM L-glutamine in a humidified incubator in 5% CO2 at 37°C under normoxic (21% or O2) hypoxic (5% O2) condition.

Reagents

The following reagents were purchased: RPMI 1640, DMEM, FBS, L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, β-mercaptoethanol, nonessential amino acids, and antibiotics from Invitrogen Life Technologies; specific ELISA kits for mouse and human CCL2 from eBioscience.

Chemicals

Temozolomide (TMZ) was obtained from Myoderm Medical Supply, Norristown, PA.

Antibodies

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-Gr1, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD45, and Tri-Color (TC)-conjugated anti-CD11b mAbs were purchased from eBioscience. Therapeutic antibodies and their respective isotype controls were provided by Centocor. The anti-mouse CCL2 mAb (C1142) neutralizes mouse CCL2/MCP-1 [24], while the anti-human CCL2 mAb (CNTO 888) neutralizes human CCL2 [25]. Each antibody is specific for its respective target ligand and does not cross-react with the other ligand (unpublished data).

Intracranial (i.c.) injection of glioma cells

The procedure used in this study has been described previously [26–29]. Briefly, using a Hamilton syringe (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV), 1×105 GL261 or U87 cells in 2 μl PBS were stereotactically injected through an entry site at the bregma, 2 mm to the right of sagittal suture, and 3 mm below the surface of the skull of anesthetized mice by using a stereotactic frame (Kopf, Tujunga, CA).

Treatment of tumor-bearing mice with anti-CCL2 mAb and/or TMZ

C57BL/6 mice bearing GL261 glioma received i.p. injections of either anti-mouse CCL2 mAb or isotype control IgG twice weekly starting on day 7 after tumor cell inoculation (2 mg/kg/dose) for up to 8 weeks. SCID mice bearing U87 glioma received i.p. injections of anti-mouse CCL2 mAb, anti-human CCL2 mAb, or both anti-mouse and anti-human CCL2 mAbs, or control IgG(s) twice weekly starting on day 7 after tumor cell inoculation (2 mg/kg/dose for each mAb) for up to 8 weeks. Some glioma-bearing mice received i.p. injections of TMZ (800 μg in 100 μl PBS per dose) or control PBS every 2 days for 4 times starting from day 7 for a total of 3 cycles with 2 week intervals. Survival was determined as the number of days from tumor cell inoculation to the day that animals had to be euthanized due to clinical manifestations, such as hemiparesis, hunch-back, seizures, loss of weight (>20%), loss of appetite, neurological signs indicative of autoimmunity, among others.

Vaccinations with synthetic peptides encoding glioma-associated antigen (GAA)-epitopes and intramuscular (i.m.) injection of polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid stabilized by lysine and carboxymethylcellulose (poly-ICLC)

The procedures have been described in our previous publications [29,30]. Briefly, glioma-bearing animals received subcutaneous (s.c.) vaccinations with 100 μg of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) core128–140 and GAA peptides, 100 μg each of hgp10025–33, mEphA2682–689, mEphA2671–679, mTRP2180–188, and mGARC-177–85, emulsified in incomplete Freund Adjuvant (IFA) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Michigan, MI) on days 2, 12 and 22 after tumor inoculation. Some animals also received i.p. injections of either anti-mouse CCL2 mAb or isotype control IgG twice weekly starting on day 7 after tumor cell inoculation (2 mg/kg/dose) for up to 8 weeks. Negative control mock vaccines consisted of 100 μg of HBV core128–140 but without GAA-peptides emulsified in IFA. Poly-ICLC (kindly provided by Dr. Andres M. Salazar, Oncovir Inc, Washington, DC; 20 μg/injection in 20 μl) or mock control PBS (20 μl) was i.m. injected twice a week starting on day 2 till day 30 after tumor inoculation. All animals were monitored daily after treatment. Symptom-free survival was monitored as the primary endpoint.

Isolation of brain-infiltrating leukocytes (BILs)

BILs were isolated using methods described previously [27,29]. Briefly, mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxia and cervical dislocation, and immediately perfused with PBS through the left cardiac ventricle. Brain tissues were mechanically minced, resuspended in 70% Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich), overlaid with 37% and 30% Percoll, and centrifuged for 20 min at 500 × g. Enriched BIL populations were recovered at the 70%-37% Percoll interface.

Flow cytometry

The procedure used in the current study has been described previously [27]. Briefly, single cell suspensions were surface-stained with fluorescent dye-conjugated antibodies. Due to the small number of BILs obtained per mouse, BILs obtained from all mice in a given group (5 mice/group) were pooled and then evaluated for the relative number and phenotype of monocyte-gated BILs between groups by Coulter EPICS cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences among more than three groups was determined by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison to compare each two groups. The statistical significance of differences between two groups was determined by t test. Survival data were analyzed by logrank test. Differences were considered significant when p <0.05. All data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 4.01 software.

RESULTS

Production of CCL2 by in vitro cultured glioma cells

To verify that our model glioma cells express CCL2, we determined the CCL2 expression levels in cultured GL261 and U87 glioma cells in both normoxic (21% O2) and hypoxic (5% O2) conditions. The hypoxic condition was employed because macrophages accumulate particularly in hypoxic and poorly vascularized portions of a tumor due to the enhanced chemokine production in the hypoxic microenvironment [31] and malignant gliomas present hypoxic conditions [32,33]. As demonstrated in Figure 1, in the normoxic condition, the GL261 and the U87 cells expressed 499 ± 20 pg mouse CCL2 and 72 ± 3 pg human CCL2, respectively, per 1 × 106 cells for 24 hours. The hypoxic condition led to approximately 2- and 3-fold higher production levels of CCL2 by the GL261 and the U87 cells, with mouse CCL2 expressed at 1095 ± 36 pg and human CCL2 at 221 ± 8 pg, respectively, per 1 × 106 cells for 24 hours.

Figure 1. CCL2 production by in vitro cultured glioma cells.

Aliquots (1×106/flask) of mouse GL261 (a) or human U87 (b) glioma cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 at normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (5% O2) conditions for 96 hours. Culture supernatants were then harvested for evaluation of CCL2 production by specific ELISA. p <0.001 and p = 0.001 between the normoxic vs. hypoxic conditions for GL261 cells and U87 cells, respectively. Results are shown with mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n=3). One of two experiments with similar results is shown.

Treatment with anti-CCL2 mAbs reduces the accumulation of TAMs and MDSCs in the glioma microenvironment

To determine whether mAb-mediated CCL2 blockade inhibits accumulation of TAMs and MDSCs in gliomas in vivo, we treated GL261-bearing syngeneic C57BL/6 mice or U87-bearing SCID mice with i.p. administration of anti-mouse CCL2 mAb or both anti-mouse plus anti-human mAbs, respectively. In the latter model, we targeted both mouse and human CCL2 because human U87 glioma cells and tumor-infiltrating host cells were expected to produce human and mouse CCL2, respectively. We isolated BILs and evaluated the numbers of CD11b+CD45+ and CD11b+Gr1+ cells as TAMs and MDSCs. Although the small numbers of BILs obtained did not allow us to perform functional analyses of these cells ex vivo, the literature supports that CD11b+Gr1+ cells represent MDSCs in mice [11].

In the GL261 model, treatment with anti-mouse CCL2 mAb significantly reduced the percentage (from 63.62% to 32.69%) (Figure 2a) and the total numbers (24.2 ± 3.0 × 103/mouse vs. 5.2 ± 0.68 × 103/mouse, p=0.0008) of CD11b+CD45+ TAMs (Figure 2b). The treatment with anti-mouse CCL2 mAb also reduced the percentage and numbers of CD11b+Gr1+ MDSCs by ~35% and ~70%, respectively, compared with the control IgG treatment, (p<0.0001, the average total number of CD11b+Gr1+ MDSCs in mCCL2 mAb treated mice vs that in isotype control IgG treated mice) (Figure 2c and d). Although the numbers are smaller than those in the GL261 model, similar results were obtained in the U87 xenograft model treated with both anti-mouse and anti-human CCL2 mAbs (Figure 2e, f, g and h).

Figure 2. Anti-CCL2 mAb administration significantly reduces CD11b+CD45+ TAMs and CD11b+Gr1+ MDSCs in BILs.

C57BL/6 mice bearing GL261 glioma (a-d) received 2 mg/kg/dose (approximately 40 μg/mouse) anti-mouse CCL2 mAb or control IgG twice weekly by i.p. injections starting on day 7 after tumor cell inoculation (n=5/group). On day 24, mice were euthanized and isolated BILs were pooled from all mice in the same treatment group, and evaluated by flow cytometry for surface expression of CD11b and CD45 (a), or CD11b and Gr1 (c). Absolute numbers of CD11b+CD45+ (p = 0.0008) (b) and CD11b+Gr1+ cells (p < 0.0001) (d) per mouse were enumerated. SCID mice bearing human U87 glioma (e-h) received 2 mg/kg/dose (approximately 40 μg/mouse/dose for each mAb) both anti-mouse and anti-human CCL2 mAbs or corresponding isotype IgG twice weekly by i.p. injections starting on day 20 after tumor cell inoculation. On day 35, mice were euthanized and isolated BILs were pooled from all mice in the same treatment group (n=5/group), and evaluated by flow cytometry for surface expression of CD11b and CD45 (e), or CD11b and Gr1 (g). Absolute numbers of CD11b+CD45+ (p = 0.001) (f) and CD11b+Gr1+ cells (p = 0.0009) (h) per mouse were enumerated. Numbers in each dot plot indicate the percentage of double-positive cells in BILs; one of four experiments with similar results is shown. (b, d, f and h), In each of 4 experiments, BILs from the same group (5 mice/group) were pooled and analyzed by flow cytometry. The average number for each population per mouse was enumerated for each experiment, and combined for the total 4 experiments to obtain the mean ± SEM for each treatment group. α-mCCL2 refers to anti-mouse CCL2 antibody; α-hCCL2 refers to anti-human CCL2 antibody.

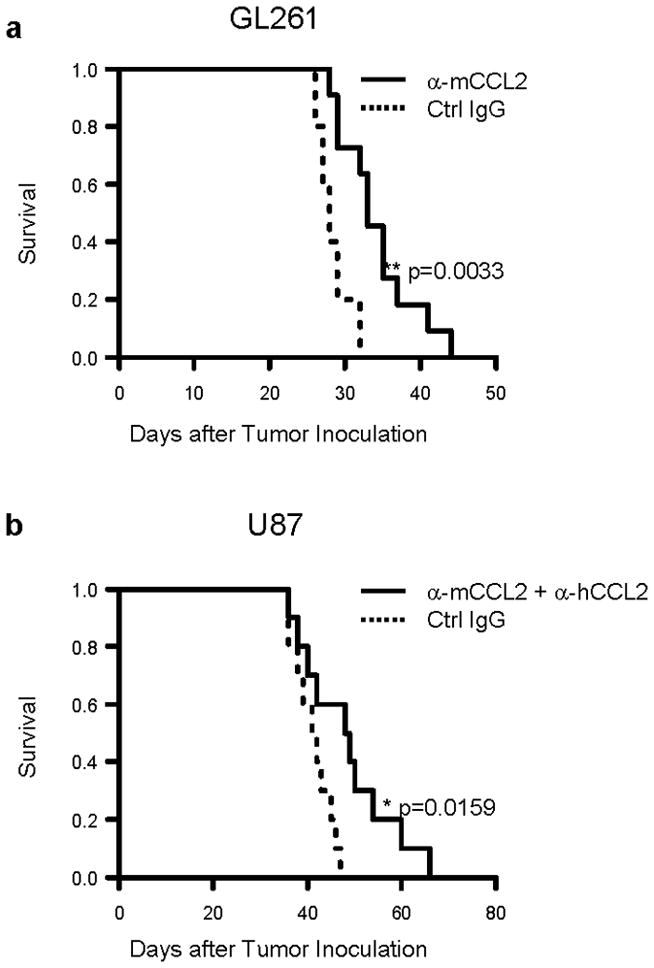

Treatment of glioma-bearing mice with anti-CCL2 mAb as monotherapy modestly prolongs survival

Results demonstrated in Figure 2 provided us with a basis for optimal mAb doses that safely achieve a substantial reduction of TAM and MDSCs in the glioma-bearing mice. We then evaluated whether the systemic CCL2 blockade by mAbs could improve the survival of these glioma bearing mice. GL261-bearing C57BL/6 mice received anti-mouse CCL2 mAb, whereas U87-bearing SCID mice were treated with both anti-mouse and anti-human CCL2 mAbs as detailed in the Materials and Methods. Treatment with anti-mouse CCL2 mAb significantly, albeit modestly, prolonged the survival of C57BL/6 mice bearing syngeneic GL261 glioma (median survival of 33 days vs. 28 days for anti-CCL2 vs. isotype IgG; p=0.0033) (Figure 3a). None of the treated mice presented neurological signs suggestive of autoimmunity. Similarly, treatment with CCL2 mAbs prolonged the survival of SCID mice bearing U87 glioma (median survival of 48.5 days vs. 41.5 days for mAb vs. control IgG groups; p=0.0159) (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. Treatment with anti-CCL2 mAb modestly prolongs the survival of glioma-bearing mice.

C57BL/6 mice bearing GL261 glioma (a) or SCID mice bearing human U87 glioma (b) were treated with anti-mouse CCL2 mAb or both anti-mouse CCL2 mAb and anti-human CCL2 mAb, respectively, by i.p. injections starting on day 7, twice weekly up to 8 weeks after tumor cell inoculation (2 mg/kg/dose for each mAb). Mice in control groups received corresponding control IgG. Symptom-free survival (SFS) of mice was monitored (for GL261 model, n=5 and 11 for control and anti-CCL2 mAb group respectively; for U87 model, n=10/group.). **p = 0.0033 for SFS of C57BL/6 mice with anti-mouse CCL2 mAb vs. that with control IgG; *p = 0.0159 for SFS of SCID mice treated with both anti-mouse and anti-human CCL2 mAbs vs. that with control IgGs. α-mCCL2 refers to anti-mouse CCL2 antibody; α-hCCL2 refers to anti-human CCL2 antibody.

Combination with chemotherapy enhances the treatment effects of the mAb-mediated CCL2 blockade

The modest improvement of survival by mAbs as monotherapy led us to investigate the efficacy of a combinatorial approach with TMZ, which, in combination with radiation therapy, is the current standard of care for newly diagnosed malignant glioma [34,35]. To this end, in each of the GL261-bearing C57BL/6 and the U87-bearing SCID mouse models, mice were stratified into each of the following 4 groups receiving: 1) TMZ and anti-CCL2 mAb(s); 2) TMZ and control IgG; 3) saline (control for TMZ) and anti-CCL2 mAb(s); or 4) saline and control IgG.

In the GL261 model, treatment with TMZ or anti-CCL2 mAb as monotherapy significantly prolonged the survival of mice (p=0.0002 for both treatment groups compared with the mock group) (Figure 4a). In particular, 2 of 7 mice receiving TMZ survived longer than 70 days whereas all control mice with mock treatments died by day 29. Strikingly, the combination of TMZ and anti-CCL2 mAb resulted in long-term survival (>70 days) in 8 of 10 mice. In contrast, in U87-bearing SCID mice, the combination of TMZ and anti-CCL2 mAbs did not enhance the therapeutic effects compared with TMZ monotherapy with 6 of 10 in the combination group and 5 of 9 mice in the TMZ monotherapy group surviving longer than 70 days.

Figure 4. Combination therapy with anti-CCL2 mAb(s) and TMZ.

C57BL/6 mice bearing GL261 glioma (a) or SCID mice bearing human U87 glioma (b) were stratified into one of four treatment groups (in each model) to receive: 1) TMZ and anti-CCL2 mAb(s) (n=10); 2) TMZ and control isotype IgG, (n=7); 3) saline (control for TMZ) and anti-CCL2 mAb(s), (n=10) or 4) saline and isotype IgG (n=7). For mAb treatment, the mice received anti-mouse CCL2 mAb or both anti-mouse CCL2 mAb and anti-human CCL2 mAb, respectively, by i.p. injections starting on day 7, twice weekly up to 8 weeks after tumor cell inoculation (2 mg/kg/dose for each mAb). TMZ (800 ug/dose) was administered i.p. starting on day 7 after tumor inoculation for a total of 2 or 3 cycles in C57BL/6 or SCID mice, respectively (see Materials and Methods). SFS of mice was monitored. (a), *p=0.0002 for anti-CCL2 mAb and saline vs. isotype IgG and saline; **p=0.0002 for isotype IgG and TMZ vs. isotype IgG and saline; ***p<0.0001 for anti-CCL2 mAb and TMZ vs. isotype IgG and saline; #p=0.0359 for anti-CCL2 mAb and TMZ vs. isotype IgG and TMZ. (b), *p=0.0218 for anti-CCL2 mAbs and saline vs. isotype IgG and saline; **p<0.0001 for isotype IgG and TMZ vs. isotype IgG and saline; ***p<0.0001 for anti-CCL2 mAbs and TMZ vs. isotype IgGs and saline; p=0.7645 for anti-CCL2 mAbs and TMZ vs. isotype IgGs and TMZ. α-mCCL2 refers to anti-mouse CCL2 antibody; α-hCCL2 refers to anti-human CCL2 antibody.

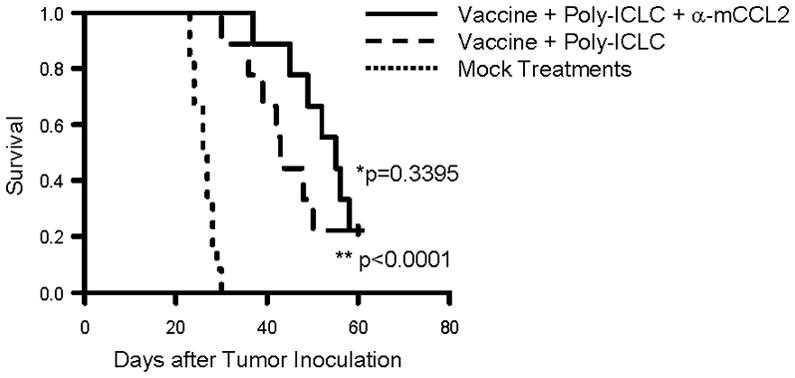

Combination with glioma vaccines does not significantly enhance the treatment effects of the mAb-mediated CCL2 blockade

We have been dedicated to development of effective immunotherapy strategies by combinations of multi-disciplinary approaches, such as vaccinations targeting glioma-associated antigens (GAAs) in combination with toll like receptor (TLR)-3 ligand poly-ICLC [29,30], or anti-TGF-β1 mAb (1D11) [36], both of which remarkably enhanced the therapeutic effects of GAA-targeting vaccines. As a logical extension of these approaches, and based on a recent study showing the benefit of anti-CCL2 mAb in combination with cancer immunotherapy in a lung cancer model [37], we evaluated whether addition of anti-CCL2 mAb would further improve the therapeutic efficacy of the combination regimen with GAA vaccines and poly-ICLC in GL261-bearing mice (Figure 5). The addition of anti-CCL2 mAb to the vaccine demonstrated a trend toward improved survival, but this did not reach statistically significant levels compared to the GAA vaccine plus poly-ICLC regimen (p=0.3395). Further studies would be required to optimize the dosing regimen for the vaccine/antibody combination for maximal efficacy.

Figure 5. Anti-CCL2 mAb administration in combination with vaccines targeting glioma-associated antigens (GAAs).

C57BL/6 mice bearing GL261 glioma received subcutaneous immunizations with 100 μg of HBV core128–140 (TPPAYRPPNAPIL) T-helper epitope peptide and GAA peptides, 100 μg each of H-2Db-binding mEphA2671–679 (FSHHNIIRL), H-2Db –binding mGARC-177–85 (AALLNKLYA), H-2Db-binding human gp100 (hgp100)25–33 (KVPRNQDWL), H-2Kb-binding mEphA2682–689 (VVSKYKPM), H-2Kb–binding mTRP2180–188 (SVYDFFVWL) peptide emulsified in Incomplete Freund Adjuvant (IFA) on days 2, 12 and 22 after tumor inoculation. In addition, poly-ICLC (20 μg/injection in 20 μl) was intramuscularly injected twice a week starting on day 2 till day 30 after tumor inoculation (n=18). Nine of 18 immunized mice were also treated with anti-mouse CCL2 mAb (2 mg/kg/dose) by i.p. injections starting on day 7, twice weekly up to 8 weeks after tumor cell inoculation (2 mg/kg/dose). Twelve control mice received mock vaccines consisted of 100 μg of HBV core128–140 but without GAA-peptides emulsified in IFA and control IgG (2 mg/kg/dose) was injected i.p. twice a week starting on day 7 for total 8 weeks after tumor inoculation. SFS of mice was monitored. (**p < 0.0001 for poly-ICLC-assisted GAA-vaccine plus anti-CCL2 mAb vs. mock-vaccines and control IgG; *p = 0.3395 for poly-ICLC-assisted GAA-vaccine plus anti-CCL2 mAb vs. poly-ICLC-assisted GAA-vaccine and isotype IgG).

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrates that systemic administration of neutralizing anti- CCL2 mAb significantly inhibits the infiltration of TAMs and MDSCs in two preclinical glioma models, thereby improving the survival of the tumor-bearing mice. The effect of anti-CCL2 mAb therapy was particularly appreciated when the mAb treatment was combined with chemotherapy with TMZ in C57BL/6 mice bearing GL261 glioma.

However, we recognize that the depletion of TAM and MDSCs was only partial, and the therapeutic effect by mAbs as monotherapy was modest. In this regard, we initially performed a number of preliminary experiments to determine the optimal dose for the most efficient depletion of TAMs and MDSCs by testing various mAb doses up to 25 mg/kg/dose. We have found that the efficacy for TAM/MDSC depletion plateaus at 2 mg/kg or higher for both the anti-CCL2 antibodies (data not shown), and thus employed 2 mg/kg/dose consistently in the current study. We think of at least two possible reasons why mAb-mediated CCL2 blockade shows moderate efficacy in preclinical glioma models. First, it is possible that the CCL2 blockade could only inhibit the attraction of monocytes from the systemic circulation into the CNS tumor site, but could not block the presence of resident microglia that already existed in the CNS. Indeed, resident microglia and bone marrow-derived macrophages in the CNS are distinguished as CD11b+CD45dim vs. CD11b+CD45high cells, respectively [38,39], and there are substantial numbers of CD11b+CD45dim residential microglia seen after the treatment with anti-mouse CCL2 mAb (Figure 2a). Another possibility is that starting therapeutic treatment at day 7 may give different results from treatment that starts earlier, as it is possible that much of the monocyte migration has occurred by the time day 7 treatment started. Thus, it may not be surprising that a therapeutic approach has modest benefit and is best combined with another therapy. Another challenge in the current approach may have been limited penetration of mAb to the CNS tumor environment. Although the blood-brain barrier is not entirely intact in the CNS tumor site, further studies are warranted to determine the distribution levels of systemically administered mAbs in the CNS tumor site [40]. Nevertheless, the significantly prolonged survival of tumor bearing mice was concomitant with the decreased accumulation of TAM and MDSC following the mAb treatments, suggesting that the accumulation of TAMs and MDSCs may have contributed to the tumor growth in our glioma models. In this regard, our recent study with mAb-mediated depletion of Gr1+ MDSCs in mouse gliomas directly demonstrated the significance of MDSCs in promotion of glioma development [41].

CCL2 has been proposed to be the principal chemokine for migration of regulatory T (Treg) cells to human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) [20]. Furthermore, it has recently been demonstrated that CCL2 blockade can augment the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy possibly through reduction of Treg cells [37], although only the combined treatment of CCL2 blockade and immunotherapy, but not CCL2 blockade alone, significantly reduced the intratumoral Tregs [37]. In our current model, we also investigated the effect of CCL2 blockade on Tregs in the glioma environment. However, CCL2 mAb treatment as a single agent did not lead to any significant reduction of intratumoral Tregs (data not shown), consistent with the referenced study [37].

With regard to the source of CCL2 in the CNS tumor environment, our data do not clearly distinguish the roles of tumor-derived vs. host immune/stroma cell-derived CCL2. In the U87 xenograft model, as the U87 glioma cells and host cells express human and mouse CCL2, respectively, and as anti-mouse and anti-human mAbs do not cross-react with CCL2 derived from other species, we initially treated U87-bearing SCID mice with either antibody separately, and evaluated the extent of TAM/MDSC depletion (data not shown). Treatment with anti-mouse CCL2 mAb appeared to have more impact on TAM/MDSC-depletion than that with the anti-human CCL2 mAb, but the combination of both had the highest impact than the use of either one of the two mAbs as a single agent, suggesting that both host- and tumor-derived CCL2 contributed to the accumulation of these immunosuppressive cell populations.

The current standard therapy for newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme following initial surgery is radiation therapy (RT) and chemotherapy with TMZ [34,35]. As the therapeutic outcome by this combination is still suboptimal, in the field of neuro-oncology, major efforts are being directed to develop novel approaches by combining new agents with RT and TMZ. Our evaluation on the combination of anti-CCL2 mAb and TMZ treatments demonstrated a remarkable improvement of survival in the GL261 model but not in the U87 model. This may be due to the following reasons: 1) the CCL2 production levels by U87 glioma cells were lower than those by GL261 cells (Figure 1), and SCID mice are immune-compromised while C57BL/6 mice are immune-competent, which correlates with lower numbers of TAM and MDSC in the tumor site in the SCID mice (Figure 2), and thus, there may have been a smaller window for appreciating the effect of CCL2 blockade; 2) human CCL2 produced by U87 cells may not be fully cross-reactive to mouse CCR2 (the cognate receptor for CCL2) on mouse monocytes, although previous studies have shown potent effects of CNTO 888 in SCID mice bearing human tumor xenografts [23]. Taken together, we speculate that CCL2 may play a lesser role in the development of U87 glioma in SCID mice than it does in GL261 gliomas. Based on the high levels of CCL2 production by GL261 cells, abundant TAM/MDSC infiltration in the CNS GL261 tumor site as well as the syngeneic immune system (i.e. no concerns for the cross-talk between human CCL2 and mouse CCR2), we think the use of C57BL/6 mice bearing GL261 and treatment with the anti-mouse CCL2 antibody is a more suitable glioma model among the two evaluated in the current study.

We have been dedicated to development of effective immunotherapy strategies by combinations of multi-disciplinary approaches, such as vaccinations targeting glioma-associated antigens (GAAs) in combination with toll like receptor (TLR)-3 ligand poly-ICLC [29,30], or anti-TGF-β1 mAb (1D11) [36], both of which remarkably enhanced the therapeutic effects of GAA-targeting vaccines. As a logical extension of these approaches, and based on a recent study showing the benefit of anti-CCL2 mAb in combination with cancer immunotherapy in a lung cancer model [37], we evaluated whether addition of anti-CCL2 mAb would further improve the therapeutic efficacy of the combination regimen with GAA vaccines and poly-ICLC in GL261-bearing mice (Figure 5). Although the addition of anti-CCL2 mAb demonstrated a trend toward improved survival, this did not reach statistically significant levels compared to the GAA vaccine plus poly-ICLC regimen (p=0.3395). Further studies both in terms of limiting mechanisms and optimization of the regimen are warranted in this direction of efforts.

In summary, we demonstrate that systemic administration of neutralizing anti-CCL2 mAbs can reduce CNS tumor infiltration of TAMs and MDSCs, thereby providing significant survival benefits in tumor-bearing mice. It is especially encouraging that increased therapeutic effects were observed when anti-CCL2 mAb was combined with TMZ in syngeneic mice bearing GL261 glioma. These observations support development of clinical trials evaluating anti-human CCL2 mAb in combination with TMZ.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Research Funding Agreement with Centocor, Inc.; the National Institute of Health (NIH; 1R01NS055140, 2P01NS40923, and 1P01CA132714)

Abbreviations

- BIL

brain infiltrating lymphocyte

- CNS

central nervous system

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

References

- 1.Mizutani K, Sud S, McGregor NA, et al. The chemokine CCL2 increases prostate tumor growth and bone metastasis through macrophage and osteoclast recruitment. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1235–42. doi: 10.1593/neo.09988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang B, Lei Z, Zhao J, et al. CCL2/CCR2 pathway mediates recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells to cancers. Cancer Lett. 2007;252:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanderkerken K, Vande BI, Eizirik DL, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), secreted by bone marrow endothelial cells, induces chemoattraction of 5T multiple myeloma cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2002;19:87–90. doi: 10.1023/a:1013891205989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohta M, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression correlates with macrophage infiltration and tumor vascularity in human esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:220–4. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valkovic T, Lucin K, Krstulja M, Dobi-Babic R, Jonjic N. Expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in human invasive ductal breast cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 1998;194:335–40. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(98)80057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lebrecht A, Grimm C, Lantzsch T, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 serum levels in patients with breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2004;25:14. doi: 10.1159/000077718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loberg RD, Ying C, Craig M, Yan L, Snyder LA, Pienta KJ. CCL2 as an important mediator of prostate cancer growth in vivo through the regulation of macrophage infiltration. Neoplasia. 2007;9:556–62. doi: 10.1593/neo.07307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin EY, Nguyen AV, Russell RG, Pollard JW. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J Exp Med. 2001;193:727–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweet MJ, Campbell CC, Sester DP, et al. Colony-stimulating factor-1 suppresses responses to CpG DNA and expression of toll-like receptor 9 but enhances responses to lipopolysaccharide in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2002;168:392–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scholl SM, Pallud C, Beuvon F, et al. Anti-colony-stimulating factor-1 antibody staining in primary breast adenocarcinomas correlates with marked inflammatory cell infiltrates and prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:120–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–74. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talmadge JE, Donkor M, Scholar E. Inflammatory cell infiltration of tumors: Jekyll or Hyde. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:373–400. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: more mechanisms for inhibiting antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0855-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshimura T, Robinson EA, Tanaka S, Appella E, Kuratsu J, Leonard EJ. Purification and amino acid analysis of two human glioma-derived monocyte chemoattractants. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1449–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.4.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshimura T, Robinson EA, Tanaka S, Appella E, Leonard EJ. Purification and amino acid analysis of two human monocyte chemoattractants produced by phytohemagglutinin-stimulated human blood mononuclear leukocytes. J Immunol. 1989;142:1956–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graeber MB, Scheithauer BW, Kreutzberg GW. Microglia in brain tumors. GLIA. 2002;40:252–9. doi: 10.1002/glia.10147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeshima H, Kuratsu J, Takeya M, Yoshimura T, Ushio Y. Expression and localization of messenger RNA and protein for monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in human malignant glioma. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:1056–62. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.6.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desbaillets I, Tada M, De Tribolet N, Diserens AC, Hamou MF, Van Meir EG. Human astrocytomas and glioblastomas express monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in vivo and in vitro. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:240–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung SY, Wong MP, Chung LP, Chan AS, Yuen ST. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression and macrophage infiltration in gliomas. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1997;93:518–27. doi: 10.1007/s004010050647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordan JT, Sun W, Hussain SF, Deangulo G, Prabhu SS, Heimberger AB. Preferential migration of regulatory T cells mediated by glioma-secreted chemokines can be blocked with chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:123–31. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0336-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuratsu J, Yoshizato K, Yoshimura T, Leonard EJ, Takeshima H, Ushio Y. Quantitative study of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in cerebrospinal fluid and cyst fluid from patients with malignant glioma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1836–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.22.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Platten M, Kretz A, Naumann U, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 increases microglial infiltration and aggressiveness of gliomas. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:388–92. doi: 10.1002/ana.10679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loberg RD, Ying C, Craig M, et al. Targeting CCL2 with Systemic Delivery of Neutralizing Antibodies Induces Prostate Cancer Tumor Regression In vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9417–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsui P, Das A, Whitaker B, et al. Generation, characterization and biological activity of CCL2 (MCP-1/JE) and CCL12 (MCP-5) specific antibodies. Hum Antibodies. 2007;16:117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carton JM, Sauerwald T, Hawley-Nelson P, et al. Codon engineering for improved antibody expression in mammalian cells. Protein Expr Purif. 2007;55:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujita M, Zhu X, Sasaki K, et al. Inhibition of STAT3 promotes the efficacy of adoptive transfer therapy using type-1 CTLs by modulation of the immunological microenvironment in a murine intracranial glioma. J Immunol. 2008;180:2089–98. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishimura F, Dusak JE, Eguchi J, et al. Adoptive transfer of Type 1 CTL mediates effective anti-central nervous system tumor response: critical roles of IFN-inducible protein-10. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4478–87. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki K, Zhu X, Vasquez C, et al. Preferential expression of very late antigen-4 on type 1 CTL cells plays a critical role in trafficking into central nervous system tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6451–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu X, Nishimura F, Sasaki K, et al. Toll like receptor-3 ligand poly-ICLC promotes the efficacy of peripheral vaccinations with tumor antigen-derived peptide epitopes in murine CNS tumor models. J Transl Med. 2007;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu X, Fallert-Junecko BA, Fujita M, et al. Poly-ICLC promotes the infiltration of effector T cells into intracranial gliomas via induction of CXCL10 in IFN-alpha and IFN-gamma dependent manners. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:1401–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0876-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis C, Murdoch C. Macrophage responses to hypoxia: implications for tumor progression and anti-cancer therapies. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:627–35. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62038-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaur B, Tan C, Brat DJ, Post DE, Van Meir EG. Genetic and hypoxic regulation of angiogenesis in gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2004;70:229–43. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-2752-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaur B, Khwaja FW, Severson EA, Matheny SL, Brat DJ, Van Meir EG. Hypoxia and the hypoxia-inducible-factor pathway in glioma growth and angiogenesis. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:134–53. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704001115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stupp R, Dietrich PY, Ostermann KS, et al. Promising survival for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme treated with concomitant radiation plus temozolomide followed by adjuvant temozolomide. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1375–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ueda R, Fujita M, Zhu X, et al. Systemic inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta in glioma-bearing mice improves the therapeutic efficacy of glioma-associated antigen peptide vaccines. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6551–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fridlender ZG, Buchlis G, Kapoor V, et al. CCL2 blockade augments cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:109–18. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ford AL, Goodsall AL, Hickey WF, Sedgwick JD. Normal adult ramified microglia separated from other central nervous system macrophages by flow cytometric sorting. Phenotypic differences defined and direct ex vivo antigen presentation to myelin basic protein-reactive CD4+ T cells compared. J Immunol. 1995;154:4309–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badie B, Schartner J. Role of microglia in glioma biology. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;54:106–13. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okada H, Kohanbash G, Zhu X, et al. Immunotherapeutic approaches for glioma. Crit Rev Immunol. 2009;29:1–42. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v29.i1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujita M, Scheurer ME, Decker SA, et al. Role of type 1 IFNs in antiglioma immunosurveillance--using mouse studies to guide examination of novel prognostic markers in humans. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3409–19. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]