Abstract

Previous studies have demonstrated that melatonin is effective in lowering intraocular pressure and that it may also protect ganglion cells. We have recently reported that, in mice lacking the melatonin receptors type 1, 25–30% ganglion cells die out by 18 months of age, suggesting that these receptors might be important for ganglion cells survival. In this study we show that the loss of ganglion cells is specific for melatonin receptors type 1 knock-out since mice lacking the melatonin receptors type 2 did not show any significant change in the number ganglion cells during aging. Furthermore, we report that melatonin receptors type 1 knock-out mice have higher intraocular pressure during the nocturnal hours than control or melatonin receptors type 2 knock-out mice at 3 and 12 months of age. Finally, our data indicate that administration of exogenous melatonin in wild-type, but not in melatonin receptors type 1 knock-out, can significantly reduce intraocular pressure. Our studies indicate that the decreased viability of ganglion cells observed in melatonin receptors type 1 knock-out mice may be a consequence of the increases in the nocturnal intraocular pressure thus suggesting that intraocular pressure levels at night and melatonin signaling should be considered as risk factor in the pathogenesis of glaucoma.

Keywords: Melatonin, Melatonin Receptors, Intraocular Pressure, Glaucoma, Ganglion Cells

Previous studies have shown that melatonin modulates many important functions within the eye [2, 20]. Melatonin exerts its influence by interacting with a family of G-protein-coupled receptors that are negatively coupled with adenylate cyclase [8]. Melatonin receptors belonging to the subtypes MT1 and MT2 have been identified in the mammalian retina. MT1 receptors are found in the inner nuclear layer (horizontal and amacrine cells), in the inner plexiform layer, in retinal ganglion cells (GCs) and in the retinal pigmented epithelium of the rat retina [6]. In humans, melatonin receptors have been located on the rod photoreceptors and on GCs [11]. In the mouse, MT1 mRNAs have been localized to photoreceptors, inner retinal neurons and GCs [5]. Previous studies have also reported that melatonin receptors are present in the ciliary body [3, , 12,13, 18]. The expression of melatonin receptors in the iris and ciliary body processes has led to the hypothesis that melatonin may be involved in the regulation of IOP and indeed several studies have shown that melatonin can modulate the IOP in several species [13–16].

However, it is worth noting that a clear dissection of the role played by melatonin and specific melatonin receptors in the mammalian eye is not well defined. This lack of data is due to the fact that the vast majority of mouse strains are genetically incapable of synthesizing melatonin in the pineal and/or retina [17] so very few studies have compared retinal physiology in melatonin-proficient and melatonin-deficient mice. Our laboratory has recently produced mice with targeted deletion of the MT1 or MT2 receptor gene in a melatonin proficient background (C3H/f+/+). These mice are capable of synthesizing melatonin, lack the MT1 or MT2 receptors, and do not develop retinal degeneration [5]. We have recently reported that removal of the MT1 receptor leads to a significant loss (25–30%) in the number of cells within the retinal ganglion cell layer (RGL) during aging [5]. Since elevated IOP is considered to be one of the most important factors that may lead to GCs loss [9] we decided to investigate the role of melatonin and melatonin receptors on the regulation of IOP.

C3H MT1−/−MT2−\− knock-out mice homozygous for the rd1 mutation, generously donated by Drs. Reppert and Weaver (University of Massachusetts Medical School), were back-crossed with C3H/f+/+ mice in which the rd1 mutation has been removed to produce C3H/f+/+MT1−/− (MT1−\−) and C3H/f+/+MT2−/− (MT2−\−) as previously reported in [5]. Mice were maintained in 12 Light: 12 Dark (LD) conditions (light on at 06:00 am and off at 06:00 pm) with food and water ad libitum.

To determine the number of cells in the RGL mice were euthanized and before eye nucleation the superior cornea was marked with a hot needle. After a 1-h fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, the anterior segment was removed, except for the superior cornea, and the eyes were fixed overnight at 4°C. After dehydration through a graded ethanol series, eyecups were embedded in Durcopan and sectioned (1.5 µm thickness) and stained with Toluidine blue. For each sample the number of cells in the RGL was counted in a 100 µm microscopic field in 10 different locations within each of three adjacent sections. The cells were counted using the Image-Pro Plus 3.0 software. The data obtained from the different adjacent sections were combined and the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) was calculated. Comparisons among the different genotypes were carried out using parametric ANOVA followed by a multiple comparison test, where appropriate. Morphometric measurements were made by observers who were blinded to the genotype and age of the samples.

To measure the IOP mice were briefly anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and the IOP was measured using a TonoLab-Tonometer (Icare Finland Ltd.). IOP was measured in each mouse at 3 hours interval during the course of the day. The IOP was measured 10 times in each mouse and time point 10 times and an average was then calculated. IOP data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. IOP measurements at Zeitgeber Time (ZT) 15, 18 and 21 (i.e., during the night) were performed under red dim light (less than 1 lux) to minimize any interference to the dark condition. To measure the effect of exogenous melatonin administration on IOP mice were briefly anesthetized and the IOP was measured as previously described and then were injected intra-peritoneally (i.p.) with 1mg/Kg of melatonin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The IOP was then measured again after 1 and 2 hrs. This dose was selected because it has been shown that it is capable of inducing physiological levels of melatonin in the eye [7] and can affect retinal function [5]. In order to avoid possible complications due to receptor desensitization, mice were injected at ZT12 (i.e., when IOP is already elevated but the endogenous melatonin levels are still low). Control animals were treated exactly as the experimental ones with the only exception that they received an injection of vehicle. Comparisons of IOPs at each time point between groups were also performed by the ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All procedures and protocols (number 10-07) were approved by the Morehouse School of Medicine Institutional Care and Use Committee.

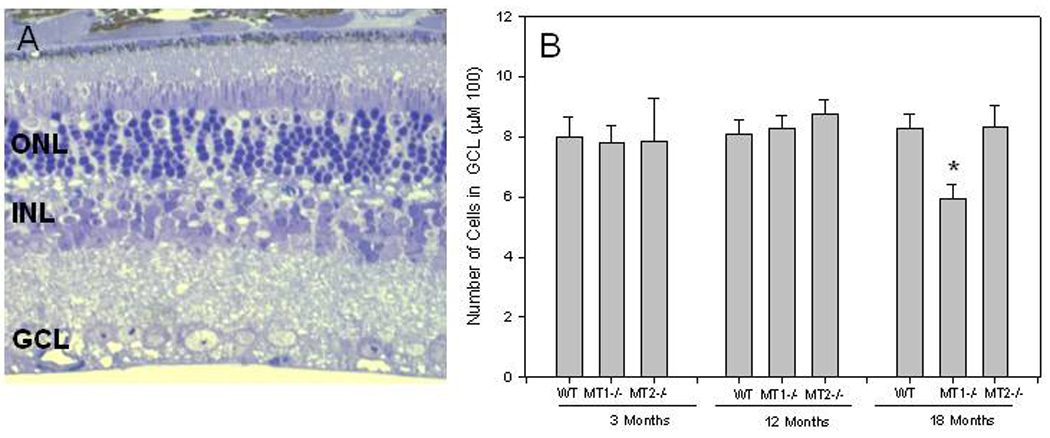

In Figure 1 A is shown a photomicrograph of the central superior retina obtained from MT2−\− mice at 18 months of age. Although MT2−\− showed a reduction in the number of cells in the photoreceptor layer similar to that observed in MT1−\− the number of cells in RGL did not show changes during aging in WT and MT2−\−. A significant change in the number of cells was observed between WT and MT1−\− and between MT1−\− and MT2−\− at 18 months of age (One-Way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak tests, P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

A) Photomicrograph of the superior central retinal of MT2−\− at the 18 months of age. Although a clear reduction in the number of cell nuclei is present in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) no changes are detectable in the inner nuclear layer (INL) or in the ganglion cell layer (GCL). B) Number of cells in the RGL in the central superior retina of WT, MT1−\− and MT2−\− mice at different ages. A significant difference in the number of cells in the RGL is present between WT and MT1−\− and MT1−\− and MT2−\− at 18 months of age. Each bar represents the mean +/− SEM; n = 4–6. *, P< 0.05 (One- Way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak tests). Data for the WT and MT1−\− have been redrawn from [4].

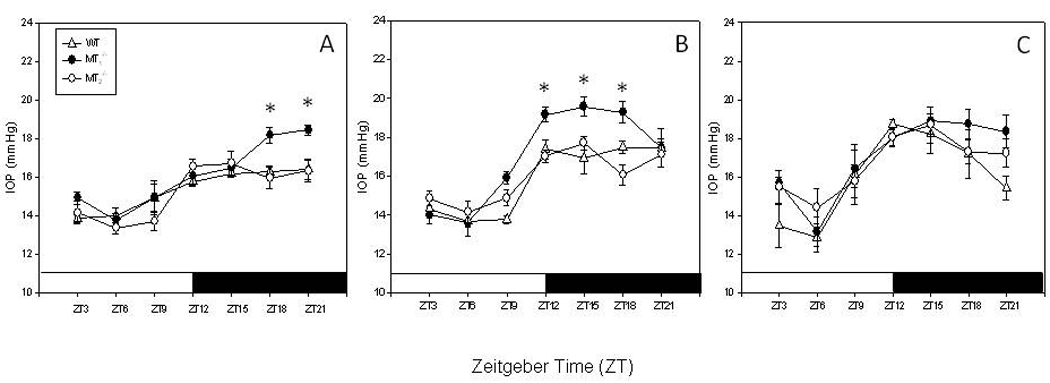

IOPs measured under LD conditions showed a significant 24-hour rhythm in all three genotypes and at the three ages (One-Way ANOVA P < 0.05) and the IOPs were low during the light phase and high during the dark phase (Figure 2A–C). When IOPs measured at each time point were compared between WT, MT1−\− and MT2−\− mice, the IOPs of MT1−\− mice at three months of age were significantly higher than those measured in age-matched WT or MT2−\− at ZT 18 and ZT 21 (Figure 2A). The same pattern was present in 12 months old mice, IOPs at night (ZT 12–18) were significantly higher in MT1−\− than those recorded in WT and MT2−\− (Figure 2B, One-Way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak test, P < 0.05). WT and MT2−\− mice at 18 months also showed a significant increase in IOP at night, although the increase in aged WT and MT2−\− was less pronounced that in MT1−\− and not significant difference was observed among the three genotypes (Figure 2 C, One-Way ANOVA P > 0.05 in all cases). No differences among the three genotypes were observed in the IOPs during the light phase (One-Way ANOVA P > 0.05 in all cases).

Figure 2.

IOPs in WT, MT1−\− and MT2−\− mice at 3 and 3 (A), 3 and 12 (B) and 18 (C) months of age. MT1−\− showed a significant increase in the IOP during the night at 12 months of age. A significant increase in the IOP was also observed in aged WT and MT2−\− (18 months) mice with respect to the values measured at 3 or 12 months (One-Way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak tests). Each point represents the mean +/− SEM. N = 4–6 for each point* < 0.05. The animals were maintained in a 12 light: 12 dark cycles. Light on at 06:00 am (ZT0) light off at 06:00 pm (ZT12). ZT=Zeitgeber Time.

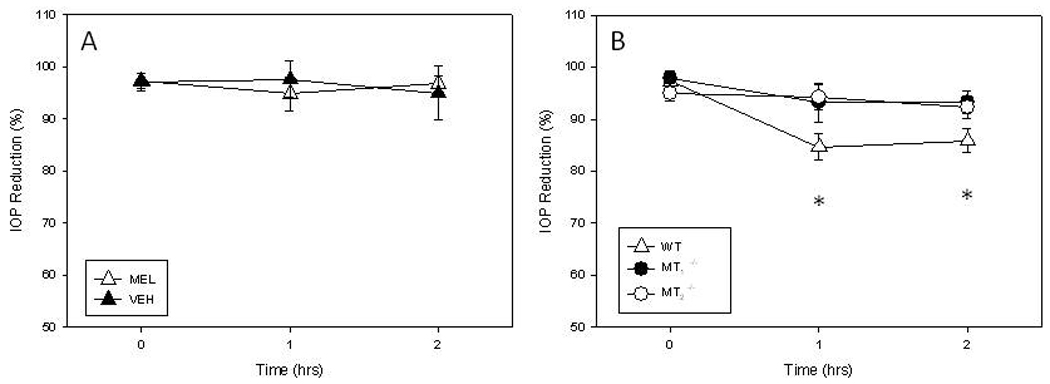

As shown in Figure 3, melatonin significantly lowered IOP levels (One-Way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak test, P < 0.05) in WT mice when injected at ZT12, but it did not have any effect when injected at in WT at ZT6 (t-test, P > 0.1) or in MT1−\− or MT2 −\− mice (One-Way ANOVA, P > 0.1 in all cases).

Figure 3.

Effect of melatonin (i.p. 1 mg/kg) injection on IOP in WT, MT1−\− and MT2−\− mice. No changes in the IOP were observed in WT mice injected at ZT6 (A, t-test, P > 0.1). Melatonin significantly suppressed IOP in WT mice when injected at ZT12 (B, One-Way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak test, P < 0.05) but no changes were observed in MT1−\− or MT2−\− mice (B). Each point represent the mean +/− SEM. N = 6–8 for each point * < 0.05

In a previous investigation we reported that MT1−\− mice show a significant reduction in the number of cell in the RGL during aging with respect to the number observed in aged matched WT mice [5]. In this study, we report that genetic removal of the MT2 receptors does not affects the viability of cells in RGL during aging (Figure 1) thus suggesting that the lost of cells in this retinal layer is specific for MT1 receptors. Our data also indicate that the changes in the number of cell in the RGL observed in MT1−\− is not a consequence of photoreceptors degeneration since MT2−\− showed a similar changes in the number of cell nuclei in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) but no changes in the number of cells in the RGL (Figure 1). Since elevated IOP is considered to be one of the most important factors that lead to GCs loss [9] we decided to investigate whether the removal of MT1 receptors would affect IOP regulation. Our data show that removal of MT1 receptors induced a small, but significant, increase in the IOPs during the nocturnal hours (Figure 2A–B). Mice lacking the MT2 receptors did not show any significant increase in the IOPs. Finally, our data indicate that administration of exogenous melatonin suppressed IOPs in WT mice, but not in MT1−\−or MT2−\− mice. The result obtained with the MT2−\− is a little bit surprising since we did not observe any effects of this receptor removal on the daily rhythm of IOP (Figure 2). Further studies will be required to fully understand the action of MT1 and MT2 receptors on IOP regulation.

The data here reported well agree with previous published studies in which the daily IOP rhythm in the mouse was demonstrated [1] and expand those data by showing that the daily pattern of IOP is preserved during aging and affected by melatonin via MT1 receptors. Indeed previous studies have implicated melatonin in the modulation of IOP [12–16]. In rabbits, a topical application of melatonin or 5-MCA-NAT (a melatonin analogue) can cause a reduction in the IOP, whereas luzindole (a non specific MT1 and MT2 receptors antagonist) abolished the effect of both compounds, thus supporting a role for MT1 or MT2 in the regulation of IOP [13]. The 5-MCA-NAT also reduced IOP in glaucomatous monkey eyes [16]. Additional studies have also reported that many melatonin antagonists, such as prazosin, DH-97 and 4-P-PDOT, reversed the effect of 5-MCA-NAT in a dose-dependent manner [14]. Finally, a very recent study in the rabbit demonstrates that 5-MCA-NAT does not act through QR2 to reduce IOP, suggesting that the effect of 5-MAC-NAT on the IOP is not mediated by MT3 [ 4] but may be mediated by MT1 or MT2 [19].

Our study further support a role for melatonin – and its receptors - in the modulation of the IOP levels that is consistent with its pattern of synthesis. Furthermore, it is worth noting that although in MT1−\− mice the increase in the IOP is small (about 2 mmHg) and only limited to the nocturnal hours, MT1−\− showed a significant decrease in the number of cells in the RGL during aging [5] thus suggesting that even a small increase in the IOP during the night may have significant effect of GCs survival. The observation that administration of exogenous melatonin in WT mice suppressed IOP only at ZT12 further suggest a role for melatonin in the modulation of IOP during the night. Further studies will be required to fully understand the mechanisms by which melatonin and its receptors regulate IOP.

IOP levels are determined by the combination of the production of aqueous humor by the ciliary epithelium and the drainage of aqueous humor, mainly through the trabecular meshwork located in the anterior chamber angle. The observation that melatonin binding sites have been observed in iris-ciliary body [12] and melatonin receptors transcripts have been reported in the ciliary body [2, 18] may suggest that melatonin via activation of MT1 can modulate aqueous humor production probably by decreasing the amount aqueous humor production at night. Previous studies have also suggested that an increase of IOP during night may represent a significant, but still unappreciated, risk factor for the development of glaucoma in humans [10]. Indeed, our new data support such a conclusion and suggest that the IOP levels at night should be considered as risk factor in the pathogenesis of glaucoma.

Previous studies have shown that MT1 receptors are present in the RGL [5,11] and therefore it is possible to speculate that the loss of cells observed in the RGL of MT1−\−mice may be a consequence of the removal of this receptors and not a consequence of the nocturnal increase in the IOP. Further studies aimed to characterize the type of cells that are dying out in MT1−\− will be necessary to address this important question. Finally, it is worth mentioning that the reduction in the number of cells in the RGL is only observed in mice at the age of 18 months. Such a result would suggest that the loss of cells in the RGL is a gradual process that occurs during the aging process in a similar manner to what has been reported in patients affected by primary open-angle glaucoma. In conclusion, we believe that our studies demonstrate that genetic ablation of MT1 increases intraocular pressure and significantly reduce the viability of cells in the RGL thus suggesting an involvement of this receptor in the pathogenesis of glaucoma.

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH grants NS-43459 and EY 28821 to G. Tosini.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aihara M, Lindsey JD, Weinreb RN. Twenty-four-hour pattern of mouse intraocular pressure. Exp. Eye Res. 2003;77:681–686. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.08.011. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alarma-Estrany P, Pintor J. Melatonin receptors in the eye: location, second messengers and role in ocular physiology. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;113:507–522. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alarma-Estrany P, Crooke A, Mediero A, Peláez T, Pintor J. Sympathetic nervous system modulates the ocular hypotensive action of MT2-melatonin receptors in normotensive rabbits. J. Pineal Res. 2008;45:468–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alarma-Estrany P, Crooke A, Pintor J. 5-MCA-NAT does not act through NQO2 to reduce intraocular pressure in New-Zealand white rabbit. J Pineal Res. 2009;47:201–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baba K, Pozdeyev N, Mazzoni F, Contreras-Alcantara S, Liu C, Kasamatsu M, Martinez-Merlos T, Strettoi E, Iuvone PM, Tosini G. Melatonin modulates visual function and cell viability in the mouse retina via the MT1 melatonin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 2009;106:15043–15048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904400106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujieda H, Hamadanizadeh SA, Wankiewicz E, Pang SF, Brown GM. Expression of mt1 melatonin receptor in rat retina: evidence for multiple cell targets for melatonin. Neuroscience. 1999;93:793–799. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle SE, Grace MS, McIvor W, Menaker M. Circadian rhythms of dopamine in mouse retina: the role of melatonin. Vis. Neurosci. 2002;19:593–601. doi: 10.1017/s0952523802195058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jockers R, Maurice P, Boutin JA, Delagrange P. Melatonin receptors, heterodimerization, signal transduction and binding sites: what's new? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007;154:1182–1195. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson TV, Tomarev SI. Rodent models of glaucoma. Brain Res Bull. 2010;81:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu JH, Bouligny RP, Kripke DF, Weinreb RN. Nocturnal elevation of intraocular pressure is detectable in the sitting position. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:4439–4442. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer P, Pache M, Loeffler KU, Brydon L, Jockers R, Flammer J, Wirz-Justice A, Savaskan E. Melatonin MT1-receptor immunoreactivity in the human eye. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1053–1057. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.9.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osborne NN, Chidlow G. The presence of functional melatonin receptors in the iris-ciliary processes of the rabbit eye. Exp. Eye Res. 1994;59:3–9. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pintor J, Martin L, Pelaez T, Hoyle CH, Peral A. Involvement of melatonin MT(3) receptors in the regulation of intraocular pressure in rabbits. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;416:251–254. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00864-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pintor J, Pelaez T, Hoyle CH, Peral A. Ocular hypotensive effects of melatonin receptor agonists in the rabbit: further evidence for an MT3 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;138:831–836. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samples JR, Krause G, Lewy AJ. Effect of melatonin on intraocular pressure. Curr. Eye Res. 1988;7:649–653. doi: 10.3109/02713688809033192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serle JB, Wang RF, Peterson WM, Plourde R, Yerxa BR. Effect of 5-MCA-NAT, a putative melatonin MT3 receptor agonist, on intraocular pressure in glaucomatous monkey eyes. J. Glaucoma. 2004;13:385–388. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000133150.44686.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tosini G, Menaker M. The clock in the mouse retina: melatonin synthesis and photoreceptor degeneration. Brain Res. 1998;789:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01446-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiechmann AF, Wirsig-Wiechmann CR. Melatonin receptor mRNA and protein expression in Xenopus laevis nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2001;73:617–623. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vincent L, Cohen W, Delagrange P, Boutin JA, Nosjean O. Molecular and cellular pharmacological properties of 5-methoxycarbonylamino-N-acetyltryptamine (MCA-NAT): a nonspecific MT3 ligand. J Pineal Res. 2010;48:222–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiechmann AF, Summers JA. Circadian rhythms in the eye: the physiological significance of melatonin receptors in ocular tissues. Prog. Ret. Eye Res. 2008;27:137–160. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]